Abstract

The 2007–2009 US economic recession was marked by unprecedented rates of housing instability and relatively little is known about how this instability impacted alcohol problems. While previous studies have linked homelessness to increased rates of alcohol use and abuse, housing instability during a recession impacts a much larger segment of the population and usually does not result in homelessness. Using a nationally representative sample of US adults, this study examines the association between housing instability during the recession and alcohol outcomes. Additionally, we assess whether this association is moderated by perceived family support. In multivariate negative binomial regressions, both trouble paying the rent/mortgage (vs. stable housing) and lost (vs. stable) housing were associated with experiencing more negative drinking consequences and alcohol dependence symptoms. However, these associations were moderated by perceived family support. In contrast to those with low perceived family support, participants with high perceived family support reported relatively few alcohol problems, irrespective of housing instability. Furthermore, while job loss was strongly associated with alcohol problems in univariate models, no significant associations between job loss and alcohol outcomes were observed in multivariate models that included indicators of housing instability. Findings point to the importance of the informal safety net and suggest that alcohol screening and abuse prevention efforts should be intensified during periods of recession, particularly among those who experience housing instability.

Keywords: Drinking consequences, Alcohol dependence, National probability sample

Introduction

The 2007–2009 US economic downturn was marked by substantial housing instability, and it is estimated that there was a nationwide reduction of 1.2 million households (either rented or owned) during the recession.1 While it is not known exactly where the occupants of these households went, estimates of an almost fivefold increase in the rates of overcrowding in some areas1 and increasing numbers of families using homeless shelters2 would suggest that many households began doubling-up with family or friends and at least some became homeless. Though most individuals were able to maintain their housing, being behind on rent or mortgage payments was common.3

While the consequences of this unprecedented housing instability are numerous, one important consideration is the impact on alcohol-related problems. Although some econometric (population-level) studies have found economic downturns to be related to reductions in volume of alcohol consumption, frequency of consumption, and liver-related mortality, others have found mixed results for heavy drinking and alcohol dependence.4–9 Furthermore, individual-level studies that focus on people who are living on the street, living in areas not meant for human habitation, or accessing emergency or transitional housing services have consistently found elevated rates of alcohol use and problems among the homeless.10–15 While important, homelessness is the most extreme form of a much larger continuum of housing instability.16 Data from the Michigan Recession and Recovery Study (MRRS) indicate that while 29.6 % of individuals living in Southeastern Michigan experienced some form of housing instability between 2007 and 2009, only 2.1 % reported homelessness in the past 12 months.3 As such, existing research on homelessness and alcohol abuse provides little insight into the most common forms of housing instability experienced by individuals during economic recessions.

Often considered to be less severe than homelessness, other forms of housing instability such as eviction/foreclosure or trouble paying the rent/mortgage nonetheless represent stressful life events that are often lengthy and protracted in nature.17 Yet, existing studies that have specifically assessed housing instability over the 2007–2009 recession and alcohol problems have yielded ambiguous results. Data from the previously mentioned Michigan Recession and Recovery Study showed that no forms of housing instability other than homelessness (AOR, 3.05; 95%CI, 1.03, 11.6) were significantly associated with harmful alcohol use at p < 0.05. However, among renters, a strong, non-significant, positive association was observed between being currently behind on the rent and harmful alcohol use (AOR, 2.99; 95%CI, 0.45, 20.1).18 In other studies, severe economic loss, defined as losing either one’s housing or job, has been associated with higher levels of negative drinking consequences and alcohol dependence.19,20 Unfortunately, these studies did not assess the independent effects of housing instability and job loss simultaneously, making it difficult to assess the relative impact of each on alcohol problems. Further studies are therefore needed to clarify previous findings, disentangle the effects of housing instability and job loss, and identify moderators which can inform future public health interventions.

Family support is one potential moderator that may help buffer individuals from alcohol-related problems during periods of housing instability in several ways. First, emotional support from family members may help minimize feelings of depression, anxiety, hopelessness, and isolation, all of which are likely to increase during housing instability and have been associated with alcohol use disorders.21–24 Secondly, instrumental support, such as providing financial assistance or a place to stay, may help mitigate the stresses associated with housing instability and, in some cases, prevent individuals from experiencing homelessness or extremely marginal housing. This type of support appears to have been common during the recession, as data from a Pew Research Center study showed that the proportion of Americans living in multi-generational family households has increased significantly over the past 5 years.25 Moreover, this same study estimates that 63 % of adults aged 18–34 have a friend or family member who moved back in with his or her parents due to the economy.25 While this implies a protective effect for family support among younger adults, 75 % of 18–34 year olds who live with their parents reported contributing to household expenses. Accordingly, residing in a multi-generation household has been associated with lower rates of poverty and may be beneficial to household members of all ages.25

Using data from the 2010 National Alcohol Survey (NAS), which began data collection during the final month of the recession,26 we examine the association between housing instability and alcohol problems. Additionally, we assess whether perceived family support moderated this association and determine which, if any, types of alcohol problems individuals were buffered against. We hypothesized that housing instability would be associated with more alcohol-related problems and that those with high perceived family support would be less likely to report housing instability. Furthermore, we hypothesized that high perceived family support would be protective against the adverse effect of recession-related housing instability on alcohol outcomes. Finally, we hypothesized that the association between housing instability and alcohol outcomes would be weaker among those with high (vs. low) perceived family support.

Methods

Sample

The 2010 National Alcohol Survey was a computer-assisted telephone interview household survey of the US adult population aged 18 or older. Data collection occurred between June 8, 2009 and March 26, 2010 and was conducted by ICF Macro, Inc. on behalf of the Alcohol Research Group. Households were first selected using list-assisted random digit dialing. If no one answered the phone, up to 15 attempts (three weekdays, seven weekday evenings, and five weekends) were made to contact that number. Once someone at a residence was reached, the Kish Grid Method27 was used to randomly select a single eligible adult per residence. All 50 states and the District of Colombia were sampled proportional to population size, except for 13 smaller states which were oversampled to ensure a minimum of 40 interviews per state. Additionally, Hispanic and black oversamples were drawn from telephone exchanges associated with geographies where at least 40 % of the population was Hispanic or black, respectively. Interviews were conducted in English and Spanish. The overall cooperation rate28 was 52.1 %, which is consistent with other telephone surveys.29 The Alcohol Research Group has conducted two types of methodological studies which collectively suggest that biases in alcohol outcomes resulting from non-response and social desirability are likely to be minimal. The first, which used data from the 1995 and 2000 NAS, compared alcohol consumption between sample replicates (each a random subsample, "opened" during the study, and with a specific response rate) and found no significant association between replicate response rate and volume of alcohol consumption (unpublished). The second compared alcohol outcomes based on identical questions used in the telephone-based 1990 Warning Labels Study and the 1990 NAS, which was conducted via face-to-face interviews and had a much higher response rate. Results indicated that while measures of alcohol consumption were comparable by survey modality,30–32 a significantly larger proportion of respondents in the telephone survey reported experiencing alcohol-related harms.33 Thus, the greater anonymity afforded to individuals participating in a telephone-based survey may actually increase the reporting of alcohol-related harms, which are the focus of this study. All participants provided verbal consent to participate and the research was approved by the Public Health Institute Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Housing Instability during the Recession

Three items were used to classify participants into mutually exclusive categories of housing instability. The first asked “Have you or another member of your household been negatively affected by the recent economic downturn or recession? That is, since January 2008?” Respondents indicating “yes” were then asked “Since January 2008, did you or anyone in your household (1) “have trouble paying rent or mortgage?,” and (2) “lose their housing, either owned or rented?” Participants were classified as having stable housing if they reported either not being negatively affected by the recession or being negatively affected but not having trouble paying the rent/mortgage or experiencing housing loss. Participants were classified as having trouble paying the rent/mortgage or lost housing based on their respective answers to those questions. Participants who reported both trouble paying the rent/mortgage and lost housing were classified as the latter.

Perceived Family Support

Perceived family support was measured using a modified version of the Family Subscale from the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (FA-MSPSS).34 Participants were asked how strongly they agreed with each of four questions regarding perceived family support: (1) “I get the emotional help and support I need from my family,” (2) “I can talk about my problems with my family,” (3) “My family really tries to help me,” and (4) “My family accepts me the way I am.” Response categories were “Not at all,” “A little,” “Somewhat,” or “Quite a lot” and scored on a scale of 0–3, with 3 indicating the highest level of support. Responses from all four questions were summed, yielding an overall score with possible values ranging from 0–12. Scores were highly skewed as 59.3 % of respondents reported a score of 12. For this reason, perceived family support was dichotomized as high support = 12 vs. low support <12.

Negative Drinking Consequences

Negative drinking consequences experienced in the past 12 months was measured by summing 15 yes/no responses from questions related to problems experienced while drinking or because of drinking. These items have been validated in prior NAS datasets35,36 and assess consequences over five domains: social (four items, such as getting into arguments while drinking), legal (three items, such as being warned by a police officer because of drinking), workplace (three items, such as drinking hurting chance for promotion), health (three items, such as illness from drinking), and injuries/accidents (two items, such as someone getting hurt or property damaged due to drinking).

Alcohol Dependence Symptoms

Dependence symptoms experienced in the past 12 months was measured by summing yes/no responses from 17 questions representing symptoms in each of the seven domains identified by the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual—4th Edition.37 Affirmative responses to multiple questions within the same domain were counted as a single symptom, resulting in a possible range of 0–7. Items from the dependence scale have been validated in prior NAS datasets.38

Additional Covariates

Additional covariates included demographics, history of heavy drinking, alcohol-related health problems prior to the recession, parental history of alcoholism, and other hardships encountered during the recession. Demographic and alcohol history variables were included as key confounders because prior work has indicated that disadvantaged populations may be especially vulnerable to both economic and alcohol-related problems during a recession.19 Previous research has also linked other recession-related hardships, particularly job loss, to poorer alcohol outcomes.19,39,40 In light of this, we included other recession-related hardships in our models to help identify the independent role of housing instability in negative alcohol outcomes and to provide insight into how housing loss may be contributing to the associations between job loss and alcohol outcomes noted in other studies.

Analysis

Out of 6,855 people who agreed to be interviewed, 5,307 (77.4 %) answered questions pertaining to their housing status since January 2008, and thus comprised the analytic sample. Of the 1,548 participants with missing data, 1,331 (86.0 %) terminated the survey before answering questions about recession-related hardships. Thus, non-response is unlikely to have biased our estimates of housing instability as the vast majority of missingness occurred prior to the administration of these questions.

All analyses were weighted to adjust for the probability of selection and to match the US population, as reflected by the US Census Bureau’s 2005 American Community Survey, in terms of sex, age, race/ethnicity, education, and state. For descriptive purposes, chi-square tests were used to test independence between housing instability and covariates. Next, using the number of negative drinking consequences and the number of alcohol dependence symptoms as dependent variables, we fit separate negative binomial regression models with housing instability as the independent variable. Four regressions were fit for each outcome and consisted of a (1) univariate model; (2) a multivariate model that included variables pertaining demographics, alcohol history, and perceived family support; (3) a multivariate model that included all of the covariates in model 2 plus indicators of other recession-related hardships (i.e., job loss, reduced work hours/pay, loss of retirement/savings); and (4) an interaction model that included all of the previous covariates plus interaction terms involving housing instability and perceived family support. Finally, among those who had trouble paying the rent/mortgage or lost housing, the proportion of individuals reporting any of each of the five type of negative drinking consequences and any of each of the seven DSM-IV dependence criteria were plotted as a function of perceived family support. All analyses were conducted using Stata 10.41

Results

Sample Characteristics

The distribution of the sample by demographics, history of alcohol problems, and experiencing other recession-related hardships are presented in Table 1. The majority of respondents reported stable housing (85.5 %), followed by trouble paying the rent/mortgage (11.8 %), and lost housing (2.7 %). Substantial differences in housing stability were observed by demographic factors; those who were younger, racial/ethnic minorities, and less educated were more likely to report trouble paying the rent/mortgage and housing loss. Additionally, participants with low perceived family support and who had alcohol problems prior to the recession were also more likely to report housing instability.

Table 1.

Respondent characteristics by housing instability

| Variable | Total samplea (n = 5,307) Wtd. column% (n) | Levels of housing stability within each covariate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lost housinga (n = 144) Wtd. row% (n) | Trouble paying rent/mortgagea (n = 627) Wtd. row% (n) | Stable housinga (n = 4,536) Wtd. row% (n) | Pearson χ 2 value | ||

| Age | |||||

| 18–29 | 20.4 (432) | 5.8 (24) | 15.9 (76) | 78.3 (332) | 155.41** |

| 30–39 | 18.2 (636) | 4.5 (29) | 19.7 (120) | 75.8 (487) | |

| 40–49 | 21.0 (938) | 3.1 (28) | 15.6 (148) | 81.3 (762) | |

| 50–59 | 17.3 (1,124) | 2.8 (28) | 12.7 (150) | 84.5 (946) | |

| 60+ | 23.1 (2,062) | 1.8 (32) | 4.9 (115) | 93.3 (1,915) | |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||

| White | 68.3 (3,104) | 2.9 (52) | 10.3 (252) | 86.8 (2,800) | 126.30** |

| Hispanic | 13.2 (1,022) | 5.9 (57) | 19.8 (170) | 74.3 (795) | |

| Black | 11.1 (1,008) | 5.0 (32) | 22.3 (184) | 72.7 (792) | |

| Other | 7.4 (173) | 2.3 (3) | 17.1 (21) | 80.6 (149) | |

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 51.5 (3,389) | 3.2 (95) | 14.8 (431) | 82.0 (2,836) | 9.86 |

| Male | 48.5 (1,918) | 3.7 (49) | 12.0 (196) | 84.3 (1,673) | |

| Education | |||||

| <High school | 14.7 (612) | 5.7 (31) | 17.2 (92) | 77.1 (489) | 63.70** |

| High school or some college | 58.8 (2,704) | 4.0 (85) | 14.0 (354) | 82.0 (2,265) | |

| 4 years college | 26.5 (1,966) | 1.2 (28) | 10.1 (178) | 88.7 (1,760) | |

| Marital status | |||||

| Married/live with significant other | 64.3 (2,952) | 3.1 (83) | 12.8 (345) | 84.1 (2,524) | 7.97 |

| Other | 35.7 (2,334) | 4.2 (61) | 14.5 (279) | 81.3 (1,994) | |

| Alcohol-related health problem prior to the recession | |||||

| Yes | 14.5 (660) | 3.7 (24) | 21.1 (123) | 75.2 (513) | 46.59** |

| No | 85.5 (4,608) | 3.4 (119) | 12.1 (498) | 84.5 (3,991) | |

| Monthly heavy drinking in previous life decade | |||||

| Yes | 36.0 (801) | 5.2 (35) | 16.7 (143) | 78.1 (623) | 7.07 |

| No | 64.0 (2,182) | 3.4 (68) | 15.4 (287) | 81.2 (1,827) | |

| Had parent(s) with alcoholism | |||||

| Yes | 24.1 (1,192) | 5.5 (50) | 16.3 (171) | 78.2 (971) | 34.49* |

| No | 75.9 (4,115) | 2.8 (94) | 12.5 (456) | 84.7 (3,565) | |

| High family support | |||||

| Yes | 59.3 (2,935) | 2.9 (69) | 11.3 (286) | 85.8 (2,580) | 39.66* |

| No | 40.7 (2,323) | 4.4 (75) | 16.5 (336) | 79.1 (1,912) | |

| Lost job due to the recession | |||||

| Yes | 16.4 (721) | 13.4 (87) | 39.6 (260) | 47.0 (374) | 995.25** |

| No | 83.6 (4,578) | 1.5 (57) | 8.2 (363) | 90.3 (4,158) | |

| Reduction in work hours/pay due to the recession | |||||

| Yes | 31.5 (1,429) | 7.2 (97) | 31.8 (444) | 61.0 (888) | 861.03** |

| No | 68.5 (3,854) | 1.6 (44) | 5.0 (178) | 93.4 (3,632) | |

| Loss of retirement/savings due to the recession | |||||

| Yes | 24.3 (1,319) | 4.7 (59) | 23.7 (250) | 71.6 (1,010) | 167.42** |

| No | 75.7 (3,960) | 2.9 (79) | 10.2 (371) | 86.9 (3,510) | |

Wtd weighted

*p ≤ 0.01; **p ≤ 0.001

aMay not sum to column total due to missing values

Frequencies of Negative Drinking Consequences and Dependence Symptoms

Overall, 8.0 and 14.0 % of respondents reported experiencing at least one negative drinking consequence or alcohol dependence symptom within the past 12 months, respectively. Among those who reported at least one negative drinking consequence, the mean number of consequences reported was 2.0 (95%CI 1.6–2.4). Among those who reported at least one dependence symptom, the mean number of symptoms reported was 1.9 (95%CI 1.7–2.1). Significant differences in negative drinking consequences by housing stability were observed as 20.0 % of those who lost their housing reported at least one negative drinking consequence, followed by 12.4 % of those who had trouble paying the rent/mortgage, and 6.8 % of those with stable housing (p < 0.001). The corresponding percentages for experiencing at least one dependence symptom by housing stability were 30.3, 17.2, and 12.9 %, respectively (p < 0.01). Using DSM-IV guidelines of experiencing symptoms in three or more domains, 14.1 % of individuals who lost their housing, 4.2 % of those who had trouble paying the rent/mortgage, and 2.3 % of those with stable housing met the criteria for alcohol dependence (p < 0.001).

Main Effects of Housing Instability on Alcohol Outcomes

In univariate models, both trouble paying the rent/mortgage (vs. stable housing) and lost (vs. stable) housing were significantly associated with experiencing more negative drinking consequences and dependence symptoms. Findings were attenuated, although largely remained significant, in subsequent multivariate models that included demographics, family support, history of alcohol problems, and other recession-related hardships. Furthermore, high (vs. low) perceived family support was associated with fewer negative drinking consequences and dependence symptoms, while previous history of heavy alcohol use and problems were positively associated with these outcomes. Items pertaining to experiencing other recession-related hardships were not significant in any of the multivariate models (Table 2).

Table 2.

Negative binomial regressions predicting negative drinking consequences and DSM-IV alcohol dependence symptom criteria reported in the past 12 months

| Dependent variable | Covariate | Model 1 beta [95 % CI] | Model 2 adj. beta [95 % CI] | Model 3 adj. beta [95 % CI] | Model 4 adj. beta [95 % CI] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of negative drinking consequences (12 months) | Trouble paying the rent/mortgage (ref = stable housing) | 0.69 [0.12, 1.25]* | 0.55 [0.02, 1.08]* | 0.37 [−0.19, 0.95] | 0.88 [0.16, 1.61]* |

| Lost housing (ref = stable housing) | 2.15 [1.22, 3.08]*** | 1.15 [0.46, 1.83]*** | 0.96 [0.22, 1.71]* | 1.32 [0.42, 2.21]** | |

| High family support (ref = low family support) | −0.89 [−1.29, −0.50]*** | −0.86 [−1.25, −0.46]*** | −0.56 [−1.02, −0.10]* | ||

| Age | −0.04 [−0.06, −0.03]*** | −0.04 [−0.06, −0.02]*** | −0.04 [−0.06, −0.02]*** | ||

| Race: Non-Hispanic black (ref = Non-Hispanic white) | 0.68 [−0.05, 1.40]† | 0.62 [−0.08, 1.32]† | 0.54 [−0.14, 1.21] | ||

| Race: Hispanic (ref = Non-hispanic white) | −0.33 [−0.99, 0.33] | −0.32 [−1.01, 0.36] | −0.35 [−1.02, 0.33] | ||

| Race: Non-Hispanic other (ref = Non-Hispanic white) | −0.19 [−1.31, 0.93] | −0.14 [−1.28, 1.01] | −0.16 [−1.25, 0.94] | ||

| Male (ref = female) | 0.19 [−0.23, 0.61] | 0.19 [−0.23, 0.61] | 0.20 [−0.22, 0.61] | ||

| Education: ≤high school (ref = ≥ 4 years college) | −0.68 [−1.48, 0.13]† | −0.63 [−1.43, 0.17] | −0.59 [−1.38, 0.19] | ||

| Education: some college (ref = ≥ 4 years college) | −0.25 [−0.69, 0.20] | −0.21 [−0.67, 0.24] | −0.17 [−0.62, 0.28] | ||

| Alcohol-related health problem prior to the recession | 0.91 [0.51, 1.31]*** | 0.89 [0.50, 1.28]*** | 0.90 [0.50, 1.29]*** | ||

| Monthly heavy drinking in previous life decade | 1.78 [1.33, 2.23]*** | 1.76 [1.31, 2.20]*** | 1.77 [1.32, 2.23]*** | ||

| Had parent(s) with alcoholism | 0.50 [0.08, 0.92]* | 0.46 [0.05, 0.86]* | 0.42 [0.02, 0.81]* | ||

| Other recession-related hardship: lost job (ref = no) | 0.25 [−0.31, 0.81] | 0.20 [−0.35, 0.75] | |||

| Other recession-related hardship: reduced work hours/pay (ref = no) | 0.10 [−0.35, 0.56] | 0.11 [−0.36, 0.57] | |||

| Other recession-related hardship: lost retirement/savings (ref = no) | 0.13 [−0.35, 0.61] | 0.17 [−0.31, 0.65] | |||

| Interaction: trouble paying the rent/mortgage × high family support | −1.41 [−2.57, −0.26]* | ||||

| Interaction: lost housing × high family support | −0.66 [−2.04, 0.71] | ||||

| No. of dependence symptoms (12 months) | Trouble paying the rent/mortgage (ref = stable housing) | 0.46 [0.08, 0.84]* | 0.24 [−0.16, 0.65] | 0.37 [−0.12, 0.85] | 0.71 [0.07, 1.34]* |

| Lost housing (ref = stable housing) | 1.41 [0.76, 2.06]*** | 0.70 [0.23, 1.17]** | 0.73 [0.20, 1.27]** | 1.17 [0.58, 1.76]*** | |

| High family support (ref = low family support) | −0.47 [−0.79, −0.15]** | −0.52 [−0.84, −0.20]*** | −0.30 [−0.69, 0.08] | ||

| Age | −0.05 [−0.06, −0.04]*** | −0.05 [−0.06, −0.03]*** | −0.05 [−0.06, −0.03]*** | ||

| Race: Non-Hispanic black (ref = Non-Hispanic white) | 0.03 [−0.45, 0.50] | 0.05 [−0.45, 0.55] | 0.003 [−0.48, 0.48] | ||

| Race: Hispanic (ref = Non-hispanic white) | −0.18 [−0.61, 0.25] | −0.19 [−0.61, 0.23] | −0.18 [−0.59, 0.24] | ||

| Race: Non-Hispanic other(ref = Non-Hispanic white) | −0.58 [−1.30, 0.14] | −0.59 [−1.29, 0.11]† | −0.63 [−1.32, 0.06]† | ||

| Male (ref = female) | 0.05 [−0.27, 0.37] | 0.09 [−0.24, 0.41] | 0.08 [−0.24, 0.41] | ||

| Education: ≤ high school (ref = ≥ 4 years college) | −0.26 [−0.83, 0.30] | −0.32 [−0.86, 0.23] | −0.30 [−0.84, 0.25] | ||

| Education: some college (ref = ≥ 4 years college) | −0.29 [−0.63, 0.05]† | −0.34 [−0.68, 0.003]† | −0.31 [−0.65, 0.03]† | ||

| Alcohol-related health problem prior to the recession | 0.95 [0.61, 1.29]*** | 0.95 [0.61, 1.29]*** | 0.94 [0.60, 1.28]*** | ||

| Monthly heavy drinking in previous life decade | 1.37 [1.02, 1.72]*** | 1.40 [1.04, 1.76]*** | 1.40 [1.04, 1.76]*** | ||

| Had parent(s) with alcoholism | 0.63 [0.30, 0.97]*** | 0.69 [0.36, 1.03]*** | 0.67 [0.34, 1.01]*** | ||

| Other recession-related hardship: lost job (ref = no) | −0.17 [−0.63, 0.28] | −0.16 [−0.62, 0.29] | |||

| Other recession-related hardship: reduced work hours/pay (ref = no) | −0.01 [−0.38, 0.37] | −0.04 [−0.42, 0.35] | |||

| Other recession-related hardship: lost retirement/savings (ref = no) | −0.20 [−0.57, 0.17] | −0.17 [−0.54, 0.20] | |||

| Interaction: trouble paying the rent/mortgage × high family support | −0.77 [−1.59, 0.05]† | ||||

| Interaction: lost housing × high family support | −1.17 [−2.23, −0.10]* |

†p ≤ 0.10; *p ≤ 0.05; **p ≤ 0.01; ***p ≤ 0.001

Interactions between Housing Instability and Perceived Family Support

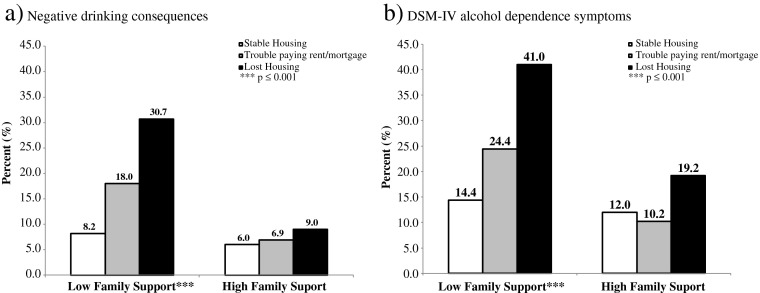

In multivariate models, significant interactions were observed between trouble paying the rent/mortgage and high perceived family support in the regression predicting negative drinking consequences and between lost housing and high perceived family support in the regression predicting alcohol dependence symptoms. The differential effect of housing instability on alcohol problems between individuals with high and low levels of family support can been seen in Fig. 1. Among participants with low perceived family support, the percent of respondents who reported at least one negative drinking consequence or at least one dependence symptom increased across the stable housing, trouble paying the rent/mortgage, and lost housing categories, respectively. However, among those with high perceived family support, housing instability had little impact on negative drinking consequences or dependence symptoms.

Fig. 1.

Percent of participants reporting at least one negative drinking consequence (a) and at least one DSM-IV alcohol dependence symptom (b) in the past 12 months by perceived family support

Types of Alcohol Problems by Perceived Family Support

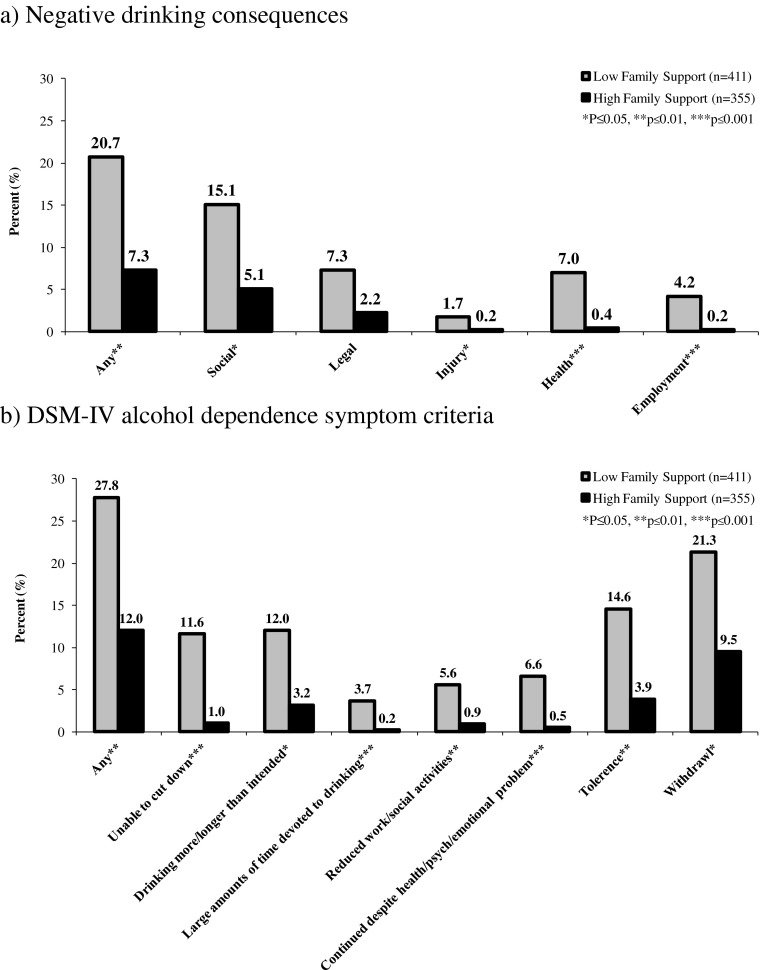

Including only participants who experienced any form of housing instability, Fig. 2 shows the percentage of individuals who reported each type of negative drinking consequence and dependence symptom by perceived family support. High (vs. low) perceived family support was associated with lower levels of all five types of negative drinking consequences and all seven DSM-IV symptom domains.

Fig. 2.

Among participants who experienced any housing instability, percent reporting each of the five types of negative drinking consequences (a) and each of the seven DSM-IV alcohol dependence symptom criteria (b) in the past 12 months by perceived family support

Discussion

This study was based on a nationally representative sample of US adults and included relatively large numbers of individuals who experienced varying degrees of housing instability over the 2007–2009 economic recession. Compared to the stably housed, individuals who experienced housing instability were more likely to report negative drinking consequences and dependence symptoms in the past year. Moreover, a dose–response relationship was observed, with increasing numbers of individuals reporting alcohol problems by the respective stable housing, trouble paying the rent/mortgage, and lost housing categories. These findings were robust and largely remained significant after controlling for demographics, alcohol history, and other recession-related hardships. This is consistent with the wider recession literature which has linked economic loss with poorer mental and physical health.42,43

While differences in methodologies, definitions of housing instability, and alcohol outcomes make it difficult to compare the results of our study to those that have previously assessed housing instability and alcohol problems during the 2007–2009 recession, some notable differences were observed. For example, the Michigan Recession and Recovery Study found that although homelessness in the past year was associated with having an alcohol use disorder, no significant associations were observed for being behind on the rent/mortgage or being evicted/foreclosed.18 This appears to be in conflict with our findings that trouble paying the rent/mortgage and lost housing were associated with more negative drinking consequences and dependence symptoms. One possible explanation for the difference between our findings and those in the MRRS is that by using the number of negative drinking consequences or dependence symptoms we are including increases in alcohol problems that occur among individuals who do not meet the criteria for having an alcohol use disorder. It is also possible that some of the individuals who reported lost housing in our sample experienced homelessness in the past year. However, only three respondents (0.0004 %) in the sample indicated that they were currently "staying in a shelter or otherwise homeless." Instead, responses such as "own my own home" (64.3 %), "rent an apt/room/home" (24.9 %), and "living in someone else's home" (10.8 %) were much more common, probably reflecting the random digit dial methodology of the National Alcohol Survey. We therefore feel that the lost housing category corresponds much more closely to the "evicted" or "foreclosed" categories in the MRRS.

Our findings also shed light on previous literature that has found positive associations between alcohol abuse and both job loss and underemployment.19,39,40 In our sample, 53.0 % of individuals who reported job loss and 39.0 % who reported reduced work hours/pay also experienced some form of housing instability. In univariate models, both job loss and reduced work hours/pay were strongly associated with experiencing more negative drinking consequences and alcohol dependence symptoms (data not shown). However, in multivariate models that included housing instability, neither job loss or reduced work hours/pay were associated with these outcomes. As housing instability likely occurs as a consequence of job loss and underemployment, it may play a key role in explaining the mechanism by which job loss and underemployment affect alcohol use and problems. At a minimum, future studies that wish to assess the direct effects of job loss and unemployment on alcohol abuse need to account for housing instability.

Finally, we found significant interactions involving housing instability and perceived family support in models predicting alcohol outcomes. Compared to individuals with low family support, those with high support reported far fewer of all types of negative drinking consequences and dependence symptoms. Moreover, the proportion of individuals who experienced any of these alcohol problems remained fairly consistent irrespective of housing instability. In contrast, among those with low perceived family support, a clear dose response was seen with increasing numbers of individuals reporting alcohol problems across the stable housing, trouble paying the rent/mortgage, and lost housing categories. High perceived family support therefore appears to have buffered individuals who experienced housing instability from a broad range of alcohol-related problems. There are several possible explanations for how this may have occurred. First, emotional support from family members may have protected individuals from negative mental health outcomes, which in turn resulted in fewer alcohol-related problems. Second, instrumental support, such as receiving financial assistance or moving back in with family members, may have buffered individuals from alcohol problems by lessening the stresses associated with housing instability. In some cases this instrumental support may even have prevented individuals becoming homeless or residing in substandard living conditions. Unfortunately, our scale only measured perceived emotional support from family and it is unclear to what extent this served as a proxy for instrumental support. As such, we cannot determine the relative contributions of emotional and instrumental support by family members on the reduction of alcohol problems. There is some evidence to support the latter explanation as it is generally accepted that social supports are most beneficial when they specifically address the immediate needs of the individual.44,45 Accordingly, previous studies have suggested that instrumental support may be especially important for mitigating the effects of economic stress.45,46 A third possibility, which cannot be ruled out, is that our findings are the result of unmeasured confounding. Both family-related factors (e.g., socioeconomic background, family size, and religiosity) and individual factors (e.g., positive or negative reporting style, resilience) may have influenced the reporting of housing instability, perceived family support, and alcohol outcomes. Future studies of housing instability should include these potential confounders as well as measures of both emotional and instrumental family support and determine the relative impact of each on alcohol problems. Furthermore, although family-based alcohol interventions have typically been targeted towards children and adolescents,47,48 our results suggest that interventions that help adults experiencing housing instability reconnect with family support systems may be beneficial in reducing alcohol-related problems. Such programs could be implemented, for example, in combination with other services offered at food banks, unemployment offices, and housing programs.49,50

These findings should be viewed in light of some limitations. First, although our results are compatible with the hypothesis that housing instability during economic recessions can lead to alcohol problems, they do not preclude the possibility of reverse causation. Controlling for alcohol use and abuse history in multivariate models should have minimized this confounding. However, individuals with existing alcohol problems may be of particular concern as having an alcohol-related health problem prior to the recession was associated with both housing instability and alcohol outcomes. These findings contribute to a growing literature which suggests that already-vulnerable populations are at increased risk for housing instability during periods of economic recession.19,51 Second, housing instability was measured by asking participants whether they or a member of their household experienced housing instability due to the recession. Some participants classified as "lost housing" or "trouble paying the rent/mortgage" may thus not have experienced housing instability themselves. The effect of housing instability on alcohol problems seems likely to be greater among those experiencing personal (vs. familial) housing instability. If so, our estimates of the relationship between housing instability and alcohol problems can be assumed to underestimate the strength of the relationship among those experiencing personal housing instability. Finally, only three individuals in our household survey reported that they were currently "living in a shelter or otherwise homeless."Our results are therefore not generalizable to individuals who experienced homelessness during the recession and caution should be taken when making inferences for this group.

These findings have important implications for mitigating the deleterious effects of housing instability on alcohol problems during future economic recessions. While addressing the needs of homeless populations should remain a top priority, our results demonstrate that individuals who experience milder forms of housing instability would also benefit from intensified alcohol screening and abuse prevention interventions. Reconnecting individuals with family support systems might be one attractive option as individuals with high perceived family support in our study reported relatively few alcohol problems, irrespective of housing instability. However, those with low perceived family support were most susceptible to alcohol problems, particularly if they also experienced some form of housing instability. As such, interventions to help those with strained family relationships (or without any living family members) develop alternate informal sources of support are also needed.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (P50AA005595, R01AA020474, and T32AA007240). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official view of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism or the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Painter G. What Happens to Household Formation in a Recession: Research Institute for Housing America, Mortgage Bankers Association; 2010.

- 2.The 2010 Annual Homeless Assessment Report to Congress: U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of Community Planning and Development; 2010.

- 3.Horowski M, Burgard S. Housing instability and health: findings from the Michigan Recession and Recovery Study. Vol 29: National Poverty Center; 2012. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Freeman DG. A note on 'Economic conditions and alcohol problems'. J Health Econ. 1999;18(5):661–670. doi: 10.1016/S0167-6296(99)00005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gerdtham UG, Ruhm CJ. Deaths rise in good economic times: evidence from the OECD. Econ Hum Biol. 2006;4(3):298–316. doi: 10.1016/j.ehb.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ruhm CJ. Economic conditions and alcohol problems. J Health Econ. 1995;14(5):583–603. doi: 10.1016/0167-6296(95)00024-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ruhm CJ, Black WE. Does drinking really decrease in bad times? J Health Econ. 2002;21(4):659–678. doi: 10.1016/S0167-6296(02)00033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dee TS. Alcohol abuse and economic conditions: evidence from repeated cross-sections of individual-level data. Health Econ. 2001;10(3):257–270. doi: 10.1002/hec.588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ettner SL. Measuring the human cost of a weak economy: does unemployment lead to alcohol abuse? Soc Sci Med. 1997;44(2):251–260. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(96)00160-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.North CS, Eyrich-Garg KM, Pollio DE, Thirthalli J. A prospective study of substance use and housing stability in a homeless population. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2010;45(11):1055–1062. doi: 10.1007/s00127-009-0144-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kushel MB, Vittinghoff E, Haas JS. Factors associated with the health care utilization of homeless persons. JAMA. 2001;285(2):200–206. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.2.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O'Toole TP, Conde-Martel A, Gibbon JL, Hanusa BH, Freyder PJ, Fine MJ. Substance-abusing urban homeless in the late 1990s: how do they differ from non-substance-abusing homeless persons? J Urban Health. 2004;81(4):606–617. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jth144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Magura S, Nwakeze PC, Rosenblum A, Joseph H. Substance misuse and related infectious diseases in a soup kitchen population. Subst Use Misuse. 2000;35(4):551–583. doi: 10.3109/10826080009147472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.D'Amore J, Hung O, Chiang W, Goldfrank L. The epidemiology of the homeless population and its impact on an urban emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2001;8(11):1051–1055. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2001.tb01114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fazel S, Khosla V, Doll H, Geddes J. The prevalence of mental disorders among the homeless in western countries: systematic review and meta-regression analysis. PLoS Med. 2008;5(12):e225. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baumohl J, ed. Homelessness in America. Westport: Oryx Press; 1996. Burt MR, ed. Chapter 2: Homelessness: definitions and counts.

- 17.Scully J, Tosi H, Banning K. Life event checklists: revisiting the social readjustment rating scale after 30 years. Educ Physhol Measures. 2000;60:864. doi: 10.1177/00131640021970952. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burgard SA, Seefeldt KS, Zelner S. Housing instability and health: findings from the Michigan recession and recovery study. Soc Sci Med. Sep 1 2012. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Zemore SE, Mulia N, Jones-Webb RJ, Liu H, Schmidt L. The 2008–2009 recession and alcohol outcomes: differential exposure and vulnerability for black and Latino populations. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2013;74(1):9–20. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2013.74.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mulia N, Zemore SE, Liu HG, Catalano R. [under review] Economic loss and alcohol problems in the 2008–9 U.S. recession: findings from the U.S. National Alcohol Survey. Emeryville, CA: Alcohol Research Group.

- 21.Lemos Vde A, Antunes HK, Baptista MN, Tufik S, De Mello MT, de Souza Formigoni ML. Low family support perception: a 'social marker' of substance dependence? Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2012;34(1):52–59. doi: 10.1590/s1516-44462012000100010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chou KL, Liang K, Sareen J. The association between social isolation and DSM-IV mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders: wave 2 of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(11):1468–1476. doi: 10.4088/JCP.10m06019gry. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Copeland WE, Angold A, Shanahan L, Dreyfuss J, Dlamini I, Costello EJ. Predicting persistent alcohol problems: a prospective analysis from the Great Smoky Mountain Study. Psychol Med. 2012;42(9):1925–1935. doi: 10.1017/S0033291711002790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blume AW, Resor MR, Villanueva MR, Braddy LD. Alcohol use and comorbid anxiety, traumatic stress, and hopelessness among Hispanics. Addict Behav. 2009;34(9):709–713. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.03.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parker K. The Boomerang Generation: feeling ok about living with mom and dad [Accessed: 2012-07-12. Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/696kkIsvp]. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center; March 15 2012.

- 26.US Bureau of Labor Statistics. The Recession of 2007–2009 [Accessed: 2012-04-25. Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/67C0xpOq3]. Washington, DC February 2012.

- 27.Kish L. Survey Sampling. New York: Wiley; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 28.The American Association for Public Opinion Research. Standard definitions: final dispositions of case codes and outcome rates for surveys. Ann Arbor, MI: The American Association for Public Opinion Research; 12/17/01 2000.

- 29.Curtin R, Presser S, Singer E. Changes in telephone survey nonresponse over the past quarter century. Public Opin Q. 2005;69(1):87–98. doi: 10.1093/poq/nfi002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Greenfield TK. Ways of measuring drinking patterns and the difference they make: experience with graduated frequencies. J Subst Abuse. 2000;12(1–2):33–49. doi: 10.1016/S0899-3289(00)00039-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Greenfield TK, Midanik LT, Rogers JD. Effects of telephone versus face-to-face interview modes on reports of alcohol consumption. Addiction. 2000;95(2):277–284. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.95227714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Midanik LT, Greenfield TK. Telephone versus in-person interviews for alcohol use: results of the 2000 National Alcohol Survey. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003;72(3):209–214. doi: 10.1016/S0376-8716(03)00204-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Midanik LT, Greenfield TK, Rogers JD. Reports of alcohol-related harm: telephone versus face-to-face interviews. J Stud Alcohol. 2001;62(1):74–78. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, Farley GK. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J Pers Assess. 1988;52(1):30–41. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa5201_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cahalan D. Problem drinkers: a national survey. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, Inc.; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Midanik L, Greenfield TK. Trends in social consequences and dependence symptoms in the United States: the National Alcohol Surveys, 1984–1995. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(1):53–56. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.90.1.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.DSM-IV: diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Caetano R, Tam TW. Prevalence and correlates of DSM-IV and ICD-10 alcohol dependence: 1990 U.S. National Alcohol Survey. Alcohol Alcohol. 1995;30(2):177–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Catalano R, Dooley D, Wilson G, Hough R. Job loss and alcohol abuse: a test using data from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area project. J Health Soc Behav. 1993;34(3):215–225. doi: 10.2307/2137203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dooley D, Prause J. Underemployment and alcohol misuse in the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth. J Stud Alcohol. 1998;59(6):669–680. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1998.59.669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stata Statistical Software: Release 10.0 [computer program]. Version. College Station, TX: Stata Corporation; 2007.

- 42.Catalano R, Goldman-Mellor S, Saxton K, et al. The health effects of economic decline. Annu Rev Public Health. 2011;32:431–450. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031210-101146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Davalos ME, French MT. This recession is wearing me out! Health-related quality of life and economic downturns. J Mental Health Policy Econ. 2011;14(2):61–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cohen LH, McGowan J, Fooskas S, Rose S. Positive life events and social support and the relationship between life stress and psychological disorder. Am J Community Psychol. 1984;12(5):567–587. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.39.5.567b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cohen S, Wills TA. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol Bull. 1985;98(2):310–357. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.98.2.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Peirce RS, Frone MR, Russell M, Cooper ML. Financial stress, social support, and alcohol involvement: a longitudinal test of the buffering hypothesis in a general population survey. Health Psychol. 1996;15(1):38–47. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.15.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Foxcroft DR, Tsertsvadze A. Universal family-based prevention programs for alcohol misuse in young people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;9 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chun TH, Linakis JG. Interventions for adolescent alcohol use. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2012;24(2):238–242. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e32834faa83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mulia N, Schmidt LA, Ye Y, Greenfield TK. Preventing disparities in alcohol screening and brief intervention: the need to move beyond primary care. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2011;35(9):1557–1560. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01501.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Girard V, Sarradon-Eck A, Payan N, 5 et al. The analysis of a mobile mental health outreach team activity: from psychiatric emergencies on the street to practice of hospitalization at home for homeless people. Presse Med. 2012;41(5):e226–e237. doi: 10.1016/j.lpm.2011.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pollack CE, Lynch J. Health status of people undergoing foreclosure in the Philadelphia region. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(10):1833–1839. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.161380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]