Abstract

The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) now recommends screening for intimate partner violence (IPV) as part of routine preventive services for women. However, there is a lack of clarity as to the most effective methods of screening and referral. We conducted a 3-year community-based mixed-method participatory research project involving four community health centers that serve as safety net medical providers for a predominately indigent urban population. The project involved preparatory work, a multifaceted systems-level demonstration project, and a sustainability period with provider/staff debriefing. The goal was to determine if a low-tech system-level intervention would result in an increase in IPV detection and response in an urban community health center. Results highlight the challenges, but also the opportunities, for implementing the new USPSTF guidelines to screen all women of childbearing years for intimate partner violence in resource-limited primary care settings.

Keywords: Intimate partner violence screening, Domestic violence, Preventative services

Introduction

The recent US Preventive Services Task Services review1 and Institute of Medicine's (IOM) report2 both recommend that intimate partner violence (IPV) screening become part of routine preventive services for women of childbearing years. These recommendations represent an important boost to almost 20 years of professional guidelines, which were for the most part ignored given that the preponderance of evidence was considered inconclusive. What tipped the balance in favor of routine IPV screening was a well-designed study3–5 that found improved IPV and pregnancy outcomes with an IPV intervention integrated into prenatal care. However, the IOM report acknowledged that there is still no recognizably preferred method of screening and intervention, which has led to generally poor screening performance among health-care professionals.6–8 Turning around this inertia is critical as we respond to the many victims of abuse. The imperative for doing so is reinforced by the population-based 2010 National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey; in the USA, women have a lifetime IPV prevalence rate of 29 %, with one in seven injured by an intimate partner.9 Moreover, there is a well-established strong link between involvement in a violent relationship, adverse physical and mental health outcomes, and high rates of health-care utilization.10–13 The health-care setting will therefore remain an important venue for identifying those experiencing IPV.

The MacMillian study14 found no difference in long-term outcomes between abused women screened prior to seeing their health-care provider compared to those screened and referred to IPV resources at the end of their health-care visit. However, IPV decreased among all women who were screened.14 This may indicate that system-level responses that pair IPV screening with an intervention may be a more successful way to improve outcomes for abused women, rather than relying solely on busy health-care providers for both IPV screening and response.15

Thus, we designed a low-tech multifaceted system-level intervention, which involved clinic staff, patients, and specially trained IPV advocates. The goal was to test whether the multi-dimensional intervention would be associated with an increase in IPV detection and referrals in busy urban community health-care settings. We also sought to identify whether an increase in the number of IPV cases identified per month could be sustained in the absence of dedicated IPV staff, an economically feasible model.

Methods

We conducted a 3-year community-based mixed-method participatory research project involving four community health centers (CHCs) that serve as safety net providers for a predominately indigent urban population in Philadelphia. The project, which was approved by two institutional review boards, involved preparatory work, a multifaceted systems-level demonstration project, and a sustainability period.

In the preparatory phase, we worked with our community partners to design and test the impact of a patient-completed paper-based Social Health Survey (Appendix A) that screens for IPV as well as other psychosocial risks in both male and female adult patients. The violence screening questions cover interpersonal victimization (physical, emotional, or sexual abuse) and perpetration risk (having an anger management problem). The goal of the Social Health Survey was to allow for patient self-disclosure of psychosocial risks prior to seeing the health-care provider. Preparatory work (briefly reported in the “Results” section) established the feasibility and acceptability of the Social Health Survey.

The demonstration project involved three components: (1) distribution of the Social Health Survey, (2) a social marketing campaign targeted at the entire health center staff, and (3) presence of a dedicated on-site trained IPV advocate, the family health advocate, trained in both motivational interviewing and IPV advocacy whose job was to assist in distributing the Social Health Survey, review the completed survey, and counsel and refer individuals who reported risk factors for IPV. The goal of the demonstration project was to test the effectiveness of this system-level intervention for increasing IPV detection and referral.

Two CHCs were given the full intervention (Social Health Survey, social marketing, and family health advocate) for 9 months, and two other CHCs (matched by size and patient demographics) were assigned to the wait-list (usual care) comparison group. Usual care in all four CHCs consists of annual provider training, IPV screening prompted by a box on the written medical record, and referral to social work for patients experiencing abuse by an intimate partner (IPV+). After completing the full intervention in the initial CHCs, the wait-list CHCs received the three-component intervention for 6 months. All CHCs were observed for sustainability for 6 months following the full intervention. Primary outcomes were monthly identification of IPV cases in each clinic, assessed by tracking family health advocate/social worker documentation before, during, and following the intervention phase. The family health advocate further assessed and provided motivational interventions for all patients identified with risk of interpersonal violence/abuse (any violence) and classified them as: (1) positive for any interpersonal violence/abuse, (2) past history of IPV, or (3) current IPV (occurring in the previous 3 months).

During the sustainability period, the services of the family health advocates were withdrawn, while the provider training, social marketing, and Social Health Survey screening continued. The goal was to test whether the CHCs would be able to sustain the number of IPV cases identified and documented, with existing staff. To promote sustainability, medical providers and social workers in each CHC were provided with additional training in IPV advocacy and motivational interviewing, while the researchers continued to monitor IPV identification and referrals.

Study Population

Our study population included both male and female patients aged 18 to 64 who received care at one of the selected CHCs during the data collection years 2010–2011. The four sites were approximately matched for patient population and volume.

Setting

The study was conducted in four of the Philadelphia Department of Public Health's (PDPH) network of county-run safety net CHCs, which serve low-income, urban, and largely minority patients, providing comprehensive medical and dental care regardless of ability to pay. Each health center has two social workers, one of whom is dedicated to a specific programmatic concern (e.g., prenatal care or HIV) and one providing for all other social health concerns. All CHC social workers participated in the study.

Data Collection

Study data were collected using a variety of measures. The Social Health Survey was used for screening purposes only and completed at the discretion of the patient. During the demonstration project, we tracked IPV+ patients identified or referred to the Family Health Advocate using formal study-related tracking forms, capturing the details related to patient demographics, type of IPV, and source of referral. During nonintervention periods (baseline, sustainability), CHC social workers documented cases of IPV using a social work log. Patient satisfaction was collected using a patient “exit” survey. Provider/staff knowledge, attitudes, behaviors, and beliefs were measured at baseline and post intervention using a modified version of the Attitudes Toward Survivors of Intimate Partner Violence provider survey.16

Outcomes

The primary outcome for the demonstration project was the number of new IPV cases identified during study baseline, intervention, and sustainability time periods. Secondary outcomes included measuring the levels of patient satisfaction and provider staff knowledge, attitudes, behaviors, and beliefs at baseline and after the system-level intervention. The CHC surveys of patient and provider factors were collected as convenience, independent cross-sectional samples.

Analysis

In order to explore the impact of the system intervention on detection of IPV, we calculated the number of IPV cases identified per month in each time period for each health center. Chi-square tests were used to assess whether the within health center differences in frequency of IPV detection were statistically different across the three time intervals (baseline, intervention, sustainability). The before/after outcomes from the cross-sectional patient satisfaction and provider survey data were compared using standard descriptive statistics.

Results

Preparation and Pilot Work

The Social Health Survey (Appendix A) was developed and piloted in four CHCs with both qualitative and quantitative data collection. First, the feasibility and impact of distributing the Social Health Survey were evaluated. During the pilot, medical record review with a random sample of 447 charts during 1 month with the social health surveys (N = 486) identified 15 newly identified diagnoses of IPV exposure, compared to no cases of IPV identified in the 447 charts randomly selected during a month without the Social Health Survey. Note the outcome for this pilot study was provider documentation alone, as opposed to the outcome for the demonstration project which was referral or identification by a family health advocate or social worker. So, it is unclear whether the newly identified IPV+ patients in the pilot received any intervention.

Preliminary data from a convenience sample of 123 patients completing the Social Health Survey during the pilot indicated that 95 % viewed physician screening of psychosocial issues to be important. The same percentage stated that they would share the attached social service referral list with others, raising the possibility that, beyond the clinical encounter, this simple low-cost intervention could contribute to an increase in community-level awareness of available IPV resources. Brief surveys and open-ended interviews were also obtained from health-care providers (N = 61) during the pilot. Half reported that the Social Health Survey increased the likelihood of discussing psychosocial health concerns and identifying cases of IPV. However, many expressed concerns about the feasibility of discussing the Social Health Survey results given the 15-min limit of patient visits.

The Demonstration Project

A multi-dimensional system-level intervention responded to provider concerns of resource limitation by providing a dedicated on-site IPV family health advocate, which, combined with additional provider training and social marketing, had a goal of increasing identification, intervention, and referral for IPV+ patients.

Intervention Phase

Family health advocates screened an average of 15 % (n = 3,270) of the approximate 21,200 patients who visited the four health centers during intervention periods (Table 1). A total of 205 patients were identified as having experienced IPV through a combination of family health advocate screening and provider referral; 194 received further assessment and intervention by the family health advocate (Table 1). Of the total IPV+ cases identified, 50 % were identified by the family health advocate, with the remainder identified through referrals from social workers (14 %), medical providers (26 %), or other health center staff (5 %) (Table 1). Most (61 %) IPV+ patients were identified through self-disclosure on the Social Health Survey. IPV+ patients were predominantly female (88 %), with the majority (67 %) reporting IPV in the past year but not in the past 3 months; 81 % disclosed victimization only, and 14 % disclosed perpetration risk. The majority of IPV+ patients also reported additional psychosocial risks, particularly depression and socioeconomic concerns.

Table 1.

Description of IPV-positive patients tracked by the family health advocate (n = 194)*

| Age | Mean (range) | 40.1 (19–62) |

| Median (std dev.) | 41 (12.5) | |

| Gender | Female | 170 (88 %) |

| Male | 24 (12 %) | |

| Race | Black/African American | 166 (86 %) |

| White | 5 (2 %) | |

| Asian | 2 (1 %) | |

| Multiracial/other | 2 (1 %) | |

| Unknown | 19 (10 %) | |

| IPV category | Past, >12 months ago | 91 (47 %) |

| Recent, not current | 39 (20 %) | |

| Recent, current | 64 (33 %) | |

| Role | Victim | 156 (81 %) |

| Perpetrator | 8 (4 %) | |

| Both | 20 (10 %) | |

| Unknown/blank | 10 (5 %) | |

| Referral source | Advocate identified | 96 (50 %) |

| Social worker | 27 (14 %) | |

| Provider | 51 (26 %) | |

| Other HC staff | 10 (5 %) | |

| Other/not specified | 10 (5 %) |

*11 additional IPV-positive patients were identified by social worker for a total n of 205

Table 2 presents information on the patients identified with any violence/abuse and further characterized by either the family health advocate or social worker during intervention periods. Most violence or abuse had occurred in the past, with approximately 16 % experiencing interpersonal violence or abuse in the past year. Only 6.2 % were determined to be currently positive for IPV, defined as physical, emotional, or sexual abuse by an intimate partner, with a third of those experiencing IPV in the past 3 months.

Table 2.

Patient engagement by health center

| Health center A | Health center B | Health center C | Health center D | Overall | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Totals (% screened) | Totals (% screened) | Totals (% screened) | Totals (% screened) | Totals (% screened) | |

| Tracked patients | 786 | 831 | 1,145 | 519 | 3,281 |

| Positive for any violence | 117 (15 %) | 150 (18 %) | 161 (14.1 %) | 109 (21 %) | 537 (16.1 %) |

| IPV-positive patients | 51 (6.5 %) | 72 (8.7 %) | 40 (3.5 %) | 42 (8.1 %) | 205 (6.2 %) |

Primary Outcome—IPV Identification

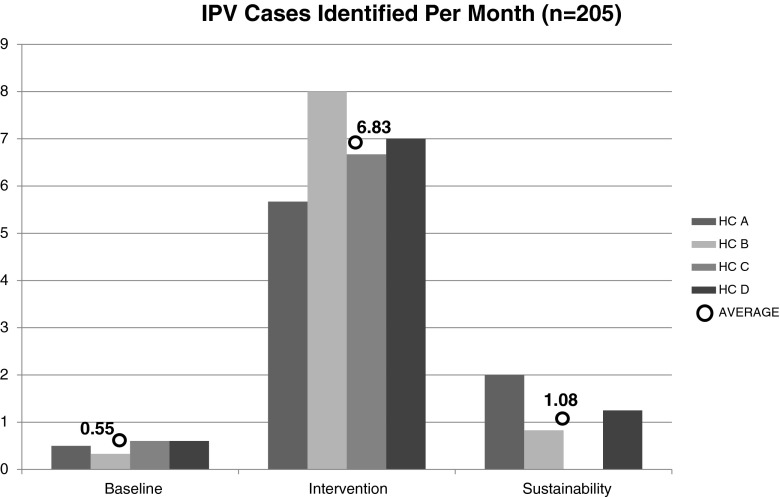

Table 3 demonstrates the impact of the system-level intervention on the number of IPV cases identified, calculated per month within each CHC for baseline, intervention, and sustainability periods. Frequencies increased from baseline during intervention periods in all four health centers and reverted to approximately baseline levels during the subsequent 6-month sustainability periods when the family health advocate was no longer present. Figure 1 visually depicts the average rate of monthly detection of new IPV cases across all four health centers during the three different time periods. There were statistically significant differences within each health center in the rates of IPV detection between baseline and intervention time periods and between intervention and sustainability periods, in all health centers (p < 0.0001). However, there were no significant differences in comparing baseline vs. sustainability periods.

Table 3.

IPV detection per month by time period

| Baseline | Intervention | Sustainability | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Per month | N | Per month | N | Per month | |

| HC A | 3 | 0.50 | 51 | 5.67 | 12* | 2.00 |

| HC B | 2 | 0.33 | 72 | 8.00 | 5 | 0.83 |

| HC C | 9 | 0.60 | 40 | 6.67 | 0 | 0.00 |

| HC D | 9 | 0.60 | 42 | 7.00 | 9 | 1.50 |

| Average | 23 | 0.55 | 205 | 6.83 | 26 | 1.08 |

*Number of months at baseline (A and B = 6 months, C and D = 15 months), intervention (A and B = 9 months; C and D = 6 months), sustainability (A, B, C, and D = 6 months)

Fig. 1.

IPV cases identified per month (n = 205 total)

Secondary Outcomes

Patient Satisfaction

Patient “exit” surveys were collected from a total of 1,575 patients—817 at baseline and 758 during the intervention. Most of the patients completing the survey were African American (75 %), born in this country (73 %), and with English as their primary language (82 %). Almost half (43 %) of the respondents were single (never married), with the majority reporting a household income of $30,000 or less (65 %). The majority (66 %) supported the idea of provider screening for abuse/conflict in relationships at routine visits. Overall patient satisfaction across the four CHCs increased from 61 % during the baseline period to 72 % during the intervention period. However, not all patients received the Social Health Survey, although there was a trend towards increased patient satisfaction when they had. For patients who completed exit surveys during intervention periods, only 19 % responded positively to the question “Did you receive the (pink) Social Health Survey?” This indicates limited receipt and distribution of the primary screening tool.

Staff/Providers

Two anonymous cross-sectional combined provider/staff surveys were conducted, at baseline (n = 134) and post intervention (n = 106) periods. Providers/staff completing the surveys were 80 % female, 78 % between the ages of 25–59 and representative of CHC employees, based on their role in the clinic; 17 % were medical providers; and 47 % provided medical support (i.e., RN, LPN, medical assistant) with the remainder providing administrative support (i.e., registration, clerical, etc.). There were no significant changes in provider/staff responses on the knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and behavior questions between baseline and the intervention or sustainability time periods (Table 4).

Table 4.

Staff survey results: baseline vs. intervention

| Overall | ||

|---|---|---|

| Baseline (n = 134) | Intervention (n = 106) | |

| % that agree/strongly agree with: | ||

| Screening female patients for violence/abuse at routine visits | 108 (81 %) | 85 (80 %) |

| Screening male patients for violence/abuse at routine visits | 97 (72 %) | 79 (75 %) |

| % that feel it is important to discuss health behaviors with patients | 122 (91 %) | 93 (88 %) |

| % that feel confident that provider's counseling will help with health behaviors | 88 (66 %) | 61 (58 %) |

| % that feel confident that provider's counseling will help with IPV | 93 (69 %) | 73 (69 %) |

| In regard to the Social Health Survey: | ||

| % that feel completion encourages provider to discuss health concerns w/ pt | 79 (59 %) | 55 (52 %) |

| % that feel it addresses actual needs and concerns of their patients | 86 (64 %) | 65 (61 %) |

| % that feel the attached resource list is helpful for their patients | 95 (71 %) | 77 (73 %) |

Informal discussions with staff and providers after study completion confirmed that the Social Health Survey was not well integrated into the routine work flow at any of the CHCs. Providers indicated that when the Social Health Survey was implemented, very high levels of depression and other psychosocial health risks, in addition to IPV, were identified. They found this overwhelming and difficult to address in the course of routine clinical care, given the short time frames for primary care visits. They strongly endorsed a need for on-site behavioral health providers.

Discussion

Our findings demonstrate that patients are willing to self-disclose violence exposure and other psychosocial risks to their health-care providers using simple self-completed questionnaires. We hypothesized that social health surveys would enable CHCs to better recognize, respond, and refer patients who were IPV+. We found that this only happened when there was a dedicated on-site IPV advocate. Results corroborate CHC provider-identified need for IPV-skilled behavioral health support if health-care settings are expected to routinely identify and provide an appropriate response to those with complex psychosocial health risks.

It is notable that the IOM's IPV recommendation does not focus on screening alone but also includes subsequent counseling.2 Historically, counseling interventions have been conducted with trained advocates associated with community-based organizations separate from health-care settings. The IOM proposes integrating these resources into medical services based on new evidence of multiple promising interventions that can reduce victimization at follow-up,17 increase safety-promoting behaviors18,19 and perceived safety,20 and also enhance well-being.21 Yet, even in successful clinical trials, interventionists struggled to successfully integrate their services into the health-care setting. For instance, Kiely et al.5 demonstrated effective screening techniques and reported measurable effects for a brief intervention delivered during prenatal care for pregnant women, but 25 % of their intervention group did not attend any counseling sessions, and only half received all the intervention components. Another intervention utilized home visits, with only a quarter of the families receiving the intervention for the recommended period of time.17 One benefit to conducting this work in a primary care setting is that patients often return for routine and follow-up care, which allows for relatively consistent delivery of services over time and relationships to develop between patients and on-site advocates.18

We did not test the on-site family health advocates as an isolated intervention. It was the combination of patient-completed Social Health Survey, provider training, and dedicated on-site advocates as part of a multifaceted intervention that resulted in the sevenfold increase in detection and intervention for IPV during the intervention periods. However, sustaining this goal was not possible without a dedicated IPV interventionist on site. This is not the first study to find a positive effect during a demonstration project that is not sustained during “business as usual.” In fact, the literature reveals that implementation and dissemination of evidence-based interventions is a challenge in many fields.22–24 While a detailed discussion of the complexity and key components of diffusion of innovations within organizations is beyond the scope of this article, a careful synthesis of previous studies and our findings identify several reasons for the CHC's failure to sustain the increase in IPV identification without dedicated staff.

First, as revealed in the provider/staff survey findings, the social marketing campaign did not change attitudes, largely because most of the providers and staff were already highly supportive of routine IPV screening and intervention. This was likely due to the on-going annual trainings and support provided by our community partners.25 Providers stated need for support staff is highlighted by the fact that over 50 % of IPV cases were identified by the family health advocates, as opposed to referrals from providers. Secondly, while staff consistently agreed that they should be screening patients regularly for violence, they distributed the social health surveys to less than 20 % of all patients. It is possible that knowledge of the limited length of the project and short-term availability of the additional resources played a role in staff willingness to invest and make long-term changes in their work flow. Indeed, after the family health advocates left, the Social Health Survey was irregularly distributed, and monthly identification and referral of IPV quickly fell to baseline levels. That being said, since study completion, three of the four CHCs continue to utilize the Social Health Survey as part of clinical care.

The fact that, similar to our study, research staff—as opposed to health-care staff—conducted much of the screening and counseling activities reported in successful clinical trials limits the transferability of these interventions to real-world settings.18,19 Indeed when studies have relied on regular staff, like ED nurses during triage, patients are not routinely screened.20 The Taft et al.21 study relied on clinicians, yet over the course of 2 years, half of enrolled clinicians did not refer a single patient for these services, even after having received 6 h of professional training centered on IPV.21 So, it is not surprising that even with our systems-level intervention, which provided: (1) an available patient-completed screening tool to facilitate self-disclosure and (2) multiple opportunities for CHC staff/providers to attend IPV trainings and information sessions, we were unable to bolster provider identification and referrals without the provision of an on-site dedicated advocate to actively seek out these referrals.

Research supports that when women are asked about conflict in their relationship,26 they are twice as likely to disclose IPV to their providers27 and report increased satisfaction with the visit.28 Multiple studies have found that patients are largely supportive of routine IPV screening during health-care visits.26,29–31 Allowing patients to self-disclose IPV involvement is one way the health-care field can begin identifying patients who want their provider to be aware of their abusive situation while not requiring providers to ask screening questions at each encounter.

The current dramatic increase in the prevalence of electronic health records (EHR)—and specifically the growing use of patient-completed data and personal health records—provides new opportunities for restructuring health system procedures in ways that can ensure that all patients are screened and receive information on needed resources. While this strategy would allow patients who are reluctant to discuss these issues with a health-care provider to still have access to resources, a recent large randomized controlled trial of computer screening plus computer-based information/referral with women at ten urban primary health-care sites found no impact on women's quality of life, health-care utilization, or IPV recurrence at 1 year.32 The authors comment that computer screening might be effective if combined with a stronger intervention.

An in-depth assessment of the mechanism and role of computer screening is demonstrated in the mixed-method study by Chang et al.,33 who found that while patients were more likely to disclose IPV, and multiple types of IPV, using self-completed computer screening, approximately 25 % only disclosed to the computer but not to the provider, and 7 % only disclosed to the provider. In follow-up interviews, patients indicated that it was easier to disclose to the computer due to being asked more specific questions in a nonjudgmental way, but they still wanted providers to follow up with in-person screening, regardless of computer results.

Given that there is now evidence of effectiveness,1 and both patients and providers supportive of routine screening and intervention for IPV and other psychosocial risks, it raises the question of how much it would cost a CHC to develop and sustain such a system. By far the most important commodity during the startup phase is the nursing and physician leadership needed to initiate a new process of care: namely, the incorporation of patient-completed psychosocial data (via paper or computer) into registration and clinical care and the identification. The financial outlays include the costs of screening and the interventionist.

The costs of paper-based social health screening mainly relate to the staff time required for distribution, collection, and filing the forms. Since most primary care sites—including safety net clinics—are adopting EHR, it is more sustainable to consider the cost of adding a touch screen computer kiosk (∼$2,000 installed with a privacy screen) to the registration process. The psychosocial risk screening instruments (both paper and computer-based versions) are available at no cost from the first author, but would require a programmer if the clinic wants to tailor the computer version to be part of their EHR. Many EHR products have the capacity to add simple patient questionnaires or link to a patient-completed document. Presumably, if the clinic is adopting an EHR system, they would have some access to technical support personnel.

The main additional resource needed to support and sustain the new process of care would be a masters-level behavioral health specialist with training and expertise in IPV, substance abuse, mental health, and motivational interviewing. The costs of making sure the dedicated behavioral health specialist has the skills and expertise in IPV intervention and referral are marginal, as local domestic violence agencies already offer these trainings for free or at very low cost to health-care providers. Partnering with a local domestic violence agency has the added advantage of creating the relationships necessary for facilitated referrals to needed legal, counseling, housing, or other social services. The behavioral health specialist would need to be culturally competent, energetic, and very knowledgeable about the community's social service resources. They would not sit in an office waiting for a referral but would be an active part of the medical team, reviewing patient-completed screening information, joining the primary care provider in the exam room, identifying need and providing counseling and referrals to community-based social services and legal resources, and possibly leading various support groups at the CHC.

While the cost of hiring a skilled IPV/behavioral health staff member will vary in different geographic areas, there is reason to think that their presence might actually save money or at least be cost neutral if they can free up medical provider time, while simultaneously improving the quality of care.34,35 In fact, behavioral health integration is considered one of the key components of the primary care medical home model that is being rolled out as a cost-saving team approach that can extend quality primary care to more patients.35,36

This study has important limitations, including those that are universal for demonstration projects that are limited in time and scope and implemented in real-world community settings. Results are primarily descriptive. Knowledge that IPV detection and referral was being studied likely created a Hawthorne effect increasing IPV detection, since the presence of research staff and data collection are not part of usual care. The distribution of patients across the three time periods may have varied given the short duration of the intervention and sustainability time periods, although this possibility seems unlikely given that identical patterns of increased detection followed by returns to baseline were observed for all CHCs. Finally, social desirability bias may have positively influenced responses on the provider and patient feedback surveys.

Conclusions

Our study suggests that, if given an opportunity, patients are willing to self-disclose IPV and other psychosocial health risks to their health-care providers. However, busy CHC staff and providers were unable to sustain IPV routine psychosocial screening into their work flow in the absence of an IPV/behavioral health specialist dedicated to addressing these issues. Future interventions aimed at improving screening and interventions for psychosocial risks, including IPV, should focus on how best to integrate patient-completed screening and appropriate response into the work flow as part of behavioral health integration in the medical home.

Acknowledgments

We want to acknowledge the many people who contributed to this work, including Alexandra Hanlon, PhD, for statistical support and our community partners: PDPH Community Health Center Clinical Directors: Rita Eburuoh, Cynthia Venegas, and Cyralene Eastmond; CHC Administrative Directors: Joan Bland, Adele Holloway, Judith Samans-Dunn, and Patricia Pate; PDPH Social Work Supervisor: Gerry Keys; the Institute for Safe Families for provider training; the Health Federation of Philadelphia: Maria Frontera and Mary White; our research staff; and family health advocates: Elizabeth Daily, Salem Valentino, Monique McDermoth, Kavita Srivastava, Tamora Williams, Katherine Watson, and all of the PDPH CHC staff and patients who participated in the study. This study received funding/support from RC1-MD-004415-02 and the First Hospital Foundation of Philadelphia.

Appendix A

References

- 1.US Preventative Services Task Force (USPSTF). Screening for intimate partner violence and abuse of elderly and vulnerable adults. Washington, D.C., 2012.

- 2.Clinical Preventive Services for Women: Closing the Gaps. Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3.El-Mohandes AA, Kiely M, Joseph JG, et al. An integrated intervention in pregnant African-Americans reduces postpartum risk: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(3):611–620. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181834b10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.El-Mohandes AA, Kiely M, Gantz MG, El-Khorazaty MN. Very preterm birth is reduced in women receiving an integrated behavioral intervention: a randomized controlled trial. Matern Child Health J. 2011;15(1):19–28. doi: 10.1007/s10995-009-0557-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kiely M, El-Mohandes AA, El-Khorazaty MN, Gantz MG. An integrated intervention to reduce intimate partner violence in pregnancy: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115(2.1):273–283. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181cbd482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Campbell JC, Coben JH, Mclaughlin E, et al. An evaluation of a system-change training model to improve emergency department response to battered women. Acad Emerg Med. 2001;8:131–138. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2001.tb01277.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rhodes KV, Frankel M, Levanthal N, Bailey J, Prenoveau E, Levinson W. You're not a victim of domestic violence, are you? Emergency provider-patient communication about domestic abuse. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(9):620–627. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-9-200711060-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rhodes KV, Kothari CL, Dichter M, Cerulli C, Wiley J, Marcus S. Intimate partner violence identification and response: time for a change. J Gen Int Med. 2010;26(8):894–899. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1662-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS) 2010 summary report. Washington, D.C. 2011.

- 10.Bonomi AE, Anderson ML, Rivara FP, Thompson RS. Health care utilization and costs associated with physical and nonphysical-only intimate partner violence. HSR: Health Serv Res. 2009;44(3):1052–1067. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2009.00955.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coker AL, Davis KE, Arias IA, et al. Physical and mental health effects of intimate partner violence for men and women. Am J Prev Med. 2002;23(4):260–268. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(02)00514-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones AS, Dienemann J, Schollenberger J, et al. Long-term costs of intimate partner violence in a sample of female HMO enrollees. Women's Health Issues. 2006;16(5):252–261. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2006.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wittenberg E, Lichter EL, Ganz ML, McCloskey LA. Community preferences for health states associated with intimate partner violence. Med Care. 2006;44(8):738–744. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000215860.58954.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.MacMillian HL, Wathen CN, Jamieson E, et al. Screening for intimate partner violence in health care settings: a randomized control trial. JAMA. 2009;302(5):493–501. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Waalen J, Goodwin MM, Sptiz AM, Petersen R, Saltzman LE. Screening for intimate partner violence by health care providers, barriers and interventions. Am J Prev Med. 2000;19:230–237. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(00)00229-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nicolaidis C, Curry MA, Gerrity M. Measuring the impact of voices of survivors program on health care workers; attitudes toward survivors of intimate partner violence. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:731–737. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0141.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bair-Merritt MH, Jennings JM, Chen R, et al. Reducing maternal intimate partner violence after the birth of a child. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164:16–23. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gillum TL, Sun CJ, Woods AB. Can a health clinic-based intervention increase safety in abused women? Results from a pilot study. J Women's Health. 2009;18:1259–1264. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2008.1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McFarlane J, Malecha A, Gist J, et al. An intervention to increase safety behaviors of abused women. Nurs Res. 2002;51:347–354. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200211000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kendall J, Pelucio MT, Casaletto J, et al. Impact of emergency department intimate partner violence intervention. J Interpersonal Violence. 2009;24:280–306. doi: 10.1177/0886260508316480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taft AJ, Small R, Hegarty KL, Watson LF, Gold L, Lumley JA. Mothers' advocates in the community (MOSAIC)—non-professional mentor support to reduce intimate partner violence and depression in mothers: a cluster randomized trial in primary care. BMC Publ Health. 2011;11:178–188. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Denis JL, Hebert Y, Langley A, Lozeau D, Trottier LH. Explaining diffusion patterns for complex health care innovations. Health Care Manage Rev. 2002;27(3):60–73. doi: 10.1097/00004010-200207000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cooper RB, Zmud RW. Information technology implementation research: a technological diffusion approach. Manag Sci. 1990;36(2):123–139. doi: 10.1287/mnsc.36.2.123. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rogers E. The Diffusion of Innovation. 4. New York, NY: Free Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harwell TS, Casten RJ, Armstrong KA, Dempsey S, Coons HL, Davis M. The results of a domestic violence training program offered to the staff of urban community health centers. Evaluation Committee of the Philadelphia Family Violence Working Group. Am J Prev Med. 1998;15(3):235–242. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00070-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Titus K. When physicians ask, women tell about domestic abuse and violence. JAMA. 1996;275:1863–1865. doi: 10.1001/jama.1996.03530480007003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hegarty KL, Taft AJ. Overcoming the barriers to disclosure and inquiry of partner abuse for women attending general practice. Aust NZ J Public Health. 2001;25:433–437. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rhodes KV, Drum M, Anliker E, Frankel RM, Howes DS, Levinson W. Lowering the threshold for discussions of domestic violence, a randomized control trial of computer screening. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1107–1114. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gerbert B, Bronstone A, Pantilat S, McPhee S, Allerton M, Moe J. When asked, patients tell: disclosure of sensitive health-risk behaviors. Med Care. 1999;37(1):104–111. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199901000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hayden SR, Barton ED, Hayden M. Domestic violence in the emergency department: how do women prefer to disclose and discuss the issues? J Emerg Med. 1997;15(4):447–451. doi: 10.1016/S0736-4679(97)00070-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Renker PR, Tonkin P. Women's views of prenatal violence screening: acceptability and confidentiality issues. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107:348–354. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000195356.90589.c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Klevens J, Kee R, Trick W, Garcia D, Anqulo FR, Jones R, Sardowski LS. Effect of screening for partner violence on women's quality of life: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2012;308(7):681–689. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.6434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chang JC, Dado DE, Schussler S, et al. In person versus computer screening for intimate partner violence among pregnant patients. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;88:443–448. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2012.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chiles JA, Lambert MJ, Hatch AH. The impact of psychological intervention on medical cost offset: a meta-analytical review. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 1999;6:204–220. doi: 10.1093/clipsy.6.2.204. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reid RJ, Coleman K, Johnson EA, et al. The group health medical home at year two: cost savings, higher patient satisfaction, and less burnout for providers. Heal Aff. 2010;29:835–843. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.DeGruy FV, Etz RS. Attending to the whole person in the patient-centered medical home: the case for incorporating mental healthcare, substance abuse care, and health behavior change. Fam Syst Health. 2010;28:298–307. doi: 10.1037/a0022049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]