Background: The PI3K/Akt signaling regulates many aspects of cardiomyocyte homeostasis.

Results: ARIA regulates cardiac PI3K/Akt signaling and modifies cardiomyocyte death and stress-induced cardiac dysfunction.

Conclusion: ARIA is a novel factor involved in the regulation of cardiac PI3K/Akt signals.

Significance: ARIA-mediated manipulation of cardiac PI3K/Akt signaling is an intriguing therapeutic target to treat cardiac dysfunction.

Keywords: Akt, Apoptosis, Cardiomyopathy, Heart Failure, PI 3-Kinase (PI3K), ARIA (Apoptosis Regulator through Modulating IAP Expression), ECSCR (Endothelial Cell Surface-expressed Chemotaxis and Apoptosis Regulator), Cardiomyocyte Death

Abstract

PI3K/Akt signaling plays an important role in the regulation of cardiomyocyte death machinery, which can cause stress-induced cardiac dysfunction. Here, we report that apoptosis regulator through modulating IAP expression (ARIA), a recently identified transmembrane protein, regulates the cardiac PI3K/Akt signaling and thus modifies the progression of doxorubicin (DOX)-induced cardiomyopathy. ARIA is highly expressed in the mouse heart relative to other tissues, and it is also expressed in isolated rat cardiomyocytes. The stable expression of ARIA in H9c2 cardiac muscle cells increased the levels of membrane-associated PTEN and subsequently reduced the PI3K/Akt signaling and the downstream phosphorylation of Bad, a proapoptotic BH3-only protein. When challenged with DOX, ARIA-expressing H9c2 cells exhibited enhanced apoptosis, which was reversed by the siRNA-mediated silencing of Bad. ARIA-deficient mice exhibited normal heart morphology and function. However, DOX-induced cardiac dysfunction was significantly ameliorated in conjunction with reduced cardiomyocyte death and cardiac fibrosis in ARIA-deficient mice. Phosphorylation of Akt and Bad was substantially enhanced in the heart of ARIA-deficient mice even after treatment with DOX. Moreover, repressing the PI3K by cardiomyocyte-specific expression of dominant-negative PI3K (p110α) abolished the cardioprotective effects of ARIA deletion. Notably, targeted activation of ARIA in cardiomyocytes but not in endothelial cells reduced the cardiac PI3K/Akt signaling and exacerbated the DOX-induced cardiac dysfunction. These studies, therefore, revealed a previously undescribed mode of manipulating cardiac PI3K/Akt signaling by ARIA, thus identifying ARIA as an attractive new target for the prevention of stress-induced myocardial dysfunction.

Introduction

The phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/phosphatase and tensin homologue deleted on the chromosome 10 (PTEN) signaling pathway regulates the biological and physiological homeostasis in cardiomyocytes (1–4). Many aspects of cardiology are regulated by the PI3K/PTEN pathway, including cell survival, myocardial hypertrophy, myocardial contractility, electrophysiology, and energy metabolism. PI3K is a lipid kinase that generates phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-phosphate, membrane phospholipids that recruit and activate 3′-phosphoinositide-dependent kinase-1 (PDK-1), and Akt (5). Akt is major signaling molecule activated by PI3K that subsequently phosphorylates a variety of downstream targets including glycogen synthase kinase 3β, mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR),2 endothelial nitric oxide synthase, and Bad (6, 7). On the other hand, PTEN is a nonredundant, plasma membrane lipid phosphatase that converts the phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-phosphate into the inactive phosphatidylinositol-4,5-diphosphate, functioning as an endogenous antagonist of PI3K (1, 8). PTEN is predominantly localized in the cytoplasm, although its substrate phospholipids bind to the plasma membrane. Because PTEN needs to associate with membrane to antagonize PI3K, the subcellular localization of PTEN is a major determinant of PTEN activity (8).

Although doxorubicin (DOX) is a powerful anticancer drug, fatal cardiotoxic effects are of concern over this drug and limit its use (9, 10). The induction of free radical formation and subsequent oxidative stress is a primary cause of DOX-mediated cardiotoxicity (9, 11, 12). This DOX-induced oxidative stress activates apoptotic signaling pathways that lead to the cardiomyocyte death. The heart is very sensitive to myocyte death, and very low levels of myocyte apoptosis (23 myocytes/105 nuclei) were sufficient to cause lethal cardiomyopathy in mice (13). Members of the Bcl-2 family regulate apoptosis, and the balance between anti- and pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 family members largely determines whether cells undergo apoptosis (14, 15). PI3K/Akt signaling directly and indirectly regulates the functions of Bcl-2 proteins and consequently protects cells from apoptosis (16–18). Furthermore, DOX can reduce the Akt activity at least in part by increasing PP1 phosphatase expression (19). Accordingly, activation of PI3K/Akt signaling suppresses DOX-induced cardiomyocyte death in vitro, and growth factor-mediated PI3K/Akt signaling is essential to protect the heart from DOX-induced injury in vivo (20–23).

We recently identified a previously uncharacterized gene, termed ARIA, that is highly expressed in endothelial cells (EC) (24). Knockdown of ARIA significantly reduced EC apoptosis in association with enhanced Akt activity. In addition, ARIA modifies the PI3K/Akt signaling by interacting with PTEN in EC (25). ARIA is a membrane protein and binds to PTEN at its intracellular domain. Therefore, ARIA anchors PTEN to the plasma membrane, enhancing the membrane-association of PTEN, which results in enhanced antagonism to PI3K. In the current study we identified significant expression of ARIA in the heart and cardiomyocytes. We demonstrate the crucial role of ARIA in the regulation of cardiac PI3K/Akt signaling and cardiac function through the analysis of the DOX-induced cardiomyopathy model using genetically modified mice including ARIA-deficient (ARIA−/−), cardiac-specific ARIA transgenic (αMHC-ARIA-Tg), EC-specific ARIA transgenic (TIE2-ARIA-Tg), and cardiac-specific dominant negative PI3K (110α) transgenic (αMHC-dnPI3K-Tg) mice. Our data revealed a unique role of ARIA in the regulation of cardiac PI3K/Akt signaling, identifying ARIA as a novel target to manipulate this important signaling pathway in the heart.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

Antibodies for phospho-Akt (Ser-473), phospho-Akt (Thr-308), total-Akt, phospho-Bad (Ser-136), total-Bad, total-PTEN, and poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology. The Na+/K+ ATPase antibody was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Antibodies against GAPDH and pancadherin were obtained from Millipore, whereas the FLAG tag antibody was obtained from Sigma. The antibody for ARIA was prepared as previously reported (24).

Cell Culture

Embryonic rat heart-derived cell line H9c2 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% FBS. Rat neonatal cardiomyocytes were isolated from 1-day-old Sprague-Dawley rats and prepared as described previously (26). Briefly, ventricular myocytes were dissociated enzymatically, and preplated for 30 min twice to enrich for cardiomyocytes. The culture medium was changed to serum-free medium after 24 h, and neonatal cardiomyocytes were cultured under serum-free conditions for 24 h before use for experiments. Transfection of target genes into rat neonatal cardiomyocytes was performed using HVJ envelope (HVJ Envelope VECTOR Kit GenomONE-Neo: Ishihara Sangyo, Japan) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Stable Lines of H9c2 Cell Lines

H9c2 cells were retrovirally transfected with GFP or ARIA. Transfected cells were then selected by culturing in the medium containing 1 μg/ml puromycin. Individual stable cell lines were clonally isolated using a cloning cup.

Quantitative PCR

Total RNA was isolated from cells or tissues by using TRIzol (Invitrogen). Complementary DNA was then synthesized by using the First Strand cDNA synthesis kit (Invitrogen). Quantitative PCR was performed with LightCycler (Roche Applied Science) and FastStart DNA Master plus SYBR Green I kit (Roche Applied Science). The expression levels of target genes were normalized to GAPDH expression. The sequences of all primers are shown in Table 1. To compare the expression levels of ARIA between cells of different species, primers were designed at the nucleotide regions with 100% homology between the species.

TABLE 1.

Nucleotide sequence of primers

| Mouse ARIA | ATGTCCTTCAGCCACAGAAGCACAC |

| CACGTTGATGTTCCTCATGGAGATG | |

| Mouse and rat ARIA | ACATCAGAGTCAGTGCTAACTGTGGCTG |

| CCATTGGCTGTGGAGCAGCTTTCAG | |

| Rat and human ARIA | GCTTCATTGTCATCCTGGTGG |

| ATTGGCTGTGGAGCAGCTTTC | |

| Mouse Top2b | AGAGAGATACGAAAGGGCGAGAGGTT |

| AGGGCATTGTCTCCTCCAGCTGAAGT | |

| Rat Top2b | GTGGAAGCACAAGAACGAGAAGACAT |

| TTCTGCTGGCGTCTGCCTTCATGGCA | |

| 18 S | CCATCCAATCGGTAGTAGCCG |

| GTAACCCGTTGAACCCCATT | |

| GAPDH | CCTTCATTGACCTCAACTACATGG |

| CCTGCTTCACCACCTTCTTGAT |

Terminal Deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated dUTP Nick-end Labeling (TUNEL) Staining in Vitro

H9c2 cells were treated with DOX for 24 h and fixed using 4% paraformaldehyde. Apoptotic cells were then detected by TUNEL method using the TUNEL AP kit (Roche Applied Science). Images were captured at eight random fields per section, and apoptosis was quantified by counting the number of TUNEL-positive nuclei. Data were expressed as a percentage of total nuclei.

TUNEL Staining in Vivo

In vivo cardiomyocyte apoptosis was evaluated by the TUNEL method using the CardioTacs kit (Trevigen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Apoptotic cells were then quantified by counting the number of TUNEL-positive myocyte nuclei at 10 random fields per section and were expressed as a percentage of total myocyte nuclei.

Preparation of Membrane Fraction

Cells were harvested from the 100-mm culture dishes and resuspended in ice-cold homogenization buffer containing 250 mm sucrose, 20 mm phosphate buffer (pH 6.8), protease inhibitor mixture (Sigma), and phosphatase inhibitors. Cells were homogenized gently on ice using a Dounce tissue grinder (Wheaton) and centrifuged at 1000 × g for 10 min to remove nuclei and cell debris. The supernatants were ultracentrifuged at 55,000 rpm for 30 min using an Optima TLX centrifuge (Beckman) with the TLA 100.3 rotor. Pellets were lysed using radioimmune precipitation assay buffer and used as the membrane fraction. The supernatants were obtained as the cytosolic fraction.

Measurement of Reactive Oxygen Species

CM-H2DCFDA (Invitrogen) was used to detect reactive oxygen species levels in H9c2 cells. Briefly, H9c2 cells were treated with DOX for 24 h. Cells were then incubated with CM-H2DCFDA at 37 °C for 30 min and washed with ice-cold PBS. Cells were then harvested, and the fluorescent intensity was measured using flow cytometry.

Measurement of Capillary Density

Cross-sections of the heart were stained with isolectin GS-IB4 from Griffonias implicifolia labeled with Alexa Fluor 568 (Invitrogen) followed by detection under a fluorescence microscope. The capillary density was quantified by measuring the number of isolectin-IB4-positive cells in six random fields per section.

Immunoblotting

Cell lysates were prepared in radioimmune precipitation assay buffer, and then immunoblotting was performed as described previously (25).

Measurement of Phosphatidylinositol 1,4,5-Trisphosphate

Phosphatidylinositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate levels were assessed using a phosphatidylinositol trisphosphate mass ELISA kit (Echelon) following the non-radioactive lipid extraction protocol provided by the manufacturer.

Generation of Transgenic Mice

We generated transgenic mice that overexpressed ARIA in cardiomyocytes under control of the αMHC promoter (αMHC-ARIA-Tg) or in EC under control of the Tie2-promotor (TIE2-ARIA-Tg). The plasmids containing the αMHC and Tie2-promoters were kind gifts from Jeffrey Robbins (The Children's Hospital Research Foundation) and Thomas N. Sato (Nara Institute of Science and Technology, Japan), respectively. The αMHC-dnPI3K (p110α)-Tg mice were a generous gift from Dr. Tetsuo Shioi (Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, Kyoto University, Japan). Mice were propagated as heterozygous Tg animals by breeding with wild-type C57BL6/J mice.

Mouse Model of DOX-induced Cardiomyopathy

Cardiomyopathy was induced by weekly intraperitoneal injection of DOX at a dose of 3 mg/kg to cumulative levels of 15 mg/kg in male mice starting at 8–10 weeks of age. The control group was injected with PBS. All mice were sacrificed and analyzed two weeks after the last injection. The Ethics Review Committee for Animal Experimentation of Kyoto Prefectural University of Medicine approved all experimental protocols.

Gene-silencing of Bad

Short interfering RNA (siRNA) for Bad was obtained from Dharmacon, and the negative control siRNA (scramble) was obtained from Ambion. Cells at ∼50% confluency were transfected with 25 nmol/liter siRNA by using Dharmafect (Dharmacon). The growth medium was replaced after 24 h, and cells were incubated for another 24 h before use.

Transthoracic Echocardiography

Echocardiography was performed 2 weeks after the last doxorubicin injection using a 30-MHz transducer (RMV 704; VisualSonics, Inc.) connected to an ultrasound system (Vevo 2100; VisualSonics). M-mode images were then recorded from parasternal short-axis images. Fractional shortening was calculated as [(LVDd − LVDs)/LVDd] × 100.

Statistics

All data are expressed as the mean ± S.D. Statistical significances between two groups were determined by unpaired Student's t test or Mann-Whitney U test. Comparisons between four or more groups were assessed for significance using non-repeated analysis of variance. When significant differences were detected, individual mean values were then compared using the Bonferroni's post hoc test. Probability values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

ARIA Is Expressed in Cardiomyocytes and Regulates Their Susceptibility to Apoptosis by Modulating PI3K/Akt Signaling

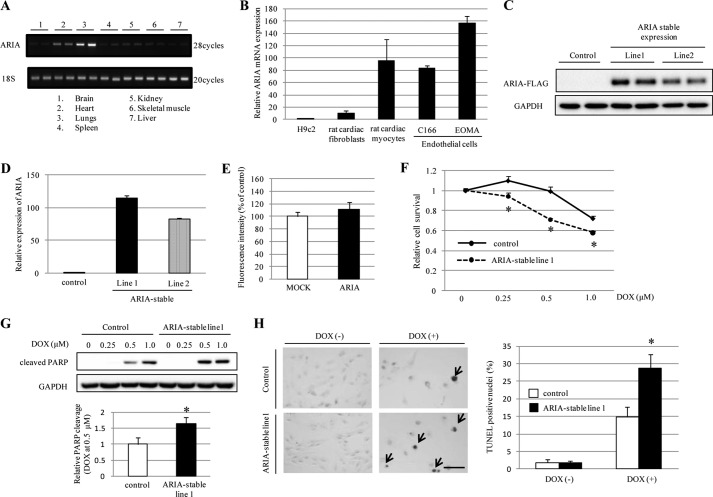

We and others have reported that ARIA is predominantly expressed in ECs (24, 27, 28). When the tissue distribution of ARIA in mice was assessed, it was noticed that ARIA was highly expressed in the heart relative to other tissues including well vascularized tissues such as the liver and kidney (Fig. 1A). We, therefore, investigated the expression of ARIA in cardiomyocytes and found that isolated rat neonatal cardiomyocytes express ARIA at the levels comparable with those in ECs (Fig. 1B). In contrast, rat neonatal cardiac fibroblasts and rat cardiac muscle cell line H9c2 demonstrated a modest and minimal expression of ARIA, respectively (Fig. 1B).

FIGURE 1.

ARIA regulates the cardiomyocyte death. A, results of RT-PCR for ARIA in various mouse tissues. B, relative mRNA expression of ARIA in H9c2 cells (rat cardiac muscle cell line), rat neonatal cardiac fibroblasts, rat neonatal cardiomyocytes, C166 (mouse endothelial cell line), and EOMA (mouse endothelial cell line) (n = 3–5). C, immunoblotting for ARIA in H9c2 cells stably expressing ARIA-FLAG by using anti-FLAG antibody. D, relative mRNA expression of ARIA in H9c2 cells stably expressing GFP (control) or ARIA (ARIA-stable) (n = 4). E, the levels of reactive oxygen species were evaluated in H9c2 cells stably expressing empty vector (MOCK) or ARIA after DOX-treatment (n = 3). F, cell viability was evaluated by MTS assay in H9c2 cells stably expressing GFP (control) or ARIA (ARIA-stable) after DOX treatment (n = 6). *, p < 0.05 versus control. G, DOX-induced apoptosis was assessed by immunoblotting for cleaved poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) (n = 3). *, p < 0.05 versus control. H, DOX (0.5 μm)-induced apoptosis was analyzed by TUNEL staining (n = 3). Arrows indicate the apoptotic cells. *, p < 0.05 versus control. Bar = 100 μm.

To investigate the potential role of ARIA in the regulation of cardiomyocyte functions, we generated two lines of H9c2 cells that stably express ARIA at levels similar to those of rat neonatal cardiomyocytes (H9c2/ARIA; Fig. 1, B–D). Because ARIA negatively regulates EC apoptosis, we first examined their susceptibility to apoptosis. When challenged with DOX, H9c2/ARIA cells exhibited reduced survival and increased apoptosis compared with control cells stably expressing GFP, but stable expression of ARIA did not enhance the oxidative stress (Fig. 1, E–H). This suggests that ARIA plays a role in the determination of stress-induced cardiomyocyte death in a cell-autonomous fashion.

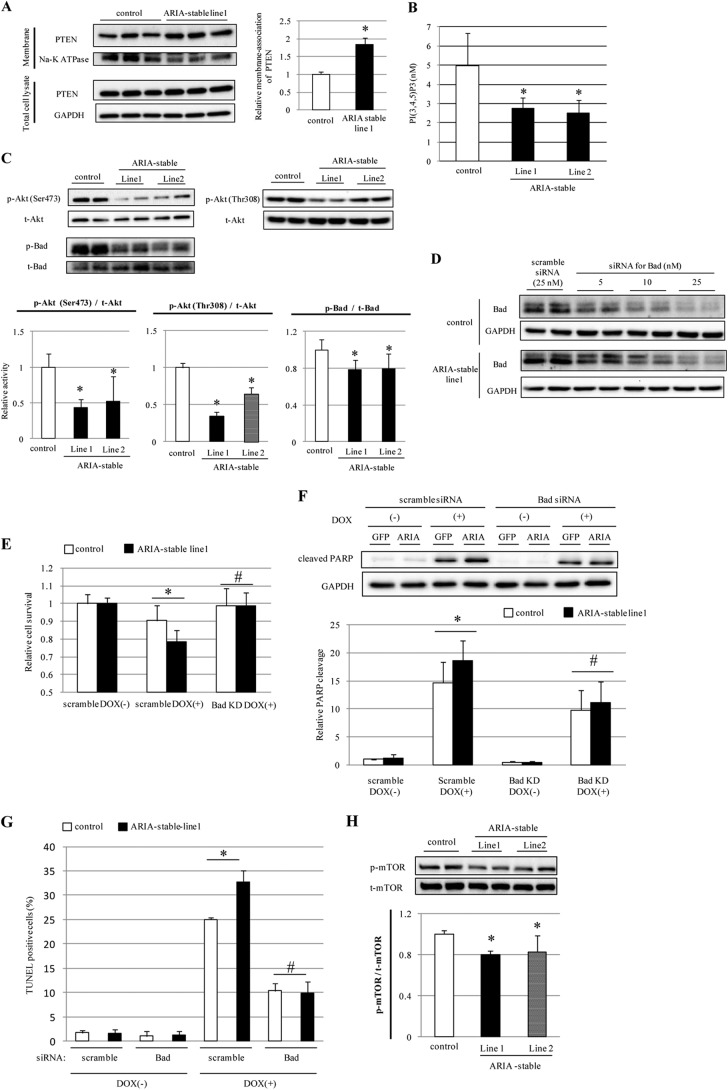

Because ARIA binds to PTEN and enhances its antagonism to PI3K in EC, we investigated whether ARIA modifies the PTEN/PI3K signaling pathways in cardiomyocytes. H9c2/ARIA cells showed enhanced levels of membrane-associated PTEN despite having expression levels of PTEN similar to control cells (Fig. 2A). Consistent with increased PTEN activity, H9c2/ARIA cells exhibited reduced membrane phosphatidylinositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate contents compared with control cells (Fig. 2B). As a result, H9c2/ARIA cells showed reduced Akt phosphorylation compared with control cells (Fig. 2C).

FIGURE 2.

ARIA regulates the cardiomyocyte apoptosis through a modification of the PI3K/Akt/Bad axis. A, expression of PTEN in the membrane fraction of H9c2 cells stably expressing GFP (control) or ARIA (ARIA-stable) (n = 6). *, p < 0.05 versus control. B, phosphatidylinositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate contents in lipid extracts of H9c2 cells stably expressing GFP (control) or ARIA (ARIA-stable) (n = 4). *, p < 0.05 versus control. C, phosphorylation of Akt and Bad was assessed by immunoblotting in H9c2 cells stably expressing GFP (control) or ARIA (ARIA-stable) (n = 6). *, p < 0.05 versus control. D, H9c2 cells stably expressing GFP (control) or ARIA (ARIA-stable) were transfected with either scramble or Bad siRNA at the indicated concentrations. E, cell survival was assessed by MTS assay in H9c2 cells stably expressing GFP (control) or ARIA (ARIA-stable) (n = 8). Cells were transfected with either scramble or Bad siRNA (Bad KD). *, p < 0.05; #, not significant versus control. F, DOX (1 μm)-induced apoptosis was analyzed by detecting the poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) cleavage (n = 6). Cells were transfected with either scramble or Bad siRNA (Bad KD). *, p < 0.05; #, not significant versus control. G, DOX (1 μm)-induced apoptosis was analyzed by TUNEL staining (n = 3). Cells were transfected with either scramble or Bad siRNA. *, p < 0.05; #, not significant versus control. H, phosphorylation of mTOR was assessed by immunoblotting in H9c2 cells stably expressing GFP (control) or ARIA (ARIA-stable) (n = 5). *, p < 0.05 versus control.

Bad is a downstream target of Akt, and its phosphorylation promotes binding to 14-3-3 and dissociation from anti-apoptotic proteins Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL, leading to the inhibition of its pro-apoptotic function (17, 29, 30). Consistent with reduced Akt activity, H9c2/ARIA cells showed reduced Bad phosphorylation and thus enhanced proapoptotic properties (Fig. 2C). Because the Akt/Bad axis is important for stress-induced cardiomyocyte death (12, 19), we examined whether this pathway plays a significant role in the ARIA-mediated modification of cardiomyocyte death. Gene silencing of Bad was successfully achieved using siRNA (Fig. 2D). Silencing of Bad completely abolished the enhanced susceptibility to apoptosis of H9c2/ARIA cells, suggesting that ARIA regulates the cardiomyocyte death via modification of the Akt/Bad axis (Fig. 2, E–G).

In addition, we explored whether ARIA modifies other Akt downstream targets than Bad. mTOR executes the most critical functions of Akt with regard to cell growth and proliferation (31). Overexpression of ARIA also reduced the phosphorylation of mTOR in H9c2 cells (Fig. 2H), suggesting that ARIA modifies the overall Akt activity in cardiomyocytes.

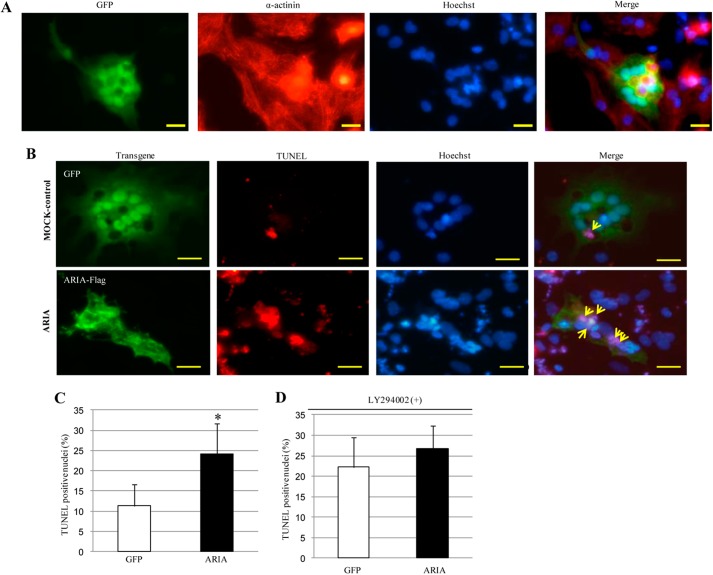

Moreover, we examined the effects of ARIA overexpression on myocyte death using rat neonatal cardiomyocytes. We confirmed the purity of isolated cardiomyocytes and successful transfection of GFP into cardiomyocytes (Fig. 3A). When apoptosis was induced by oxidative stress, cardiomyocytes overexpressing ARIA exhibited enhanced apoptosis compared with MOCK-control cells transfected with GFP (Fig. 3, B and C). Of note, proapoptotic effects of ARIA overexpression disappeared when cells were treated with PI3K inhibitor (Fig. 3D). These collectively reveal a previously undescribed pathway in the regulation of cardiac PI3K/Akt signaling by ARIA and suggest that this ARIA-mediated modification of PI3K/Akt signaling regulates the cardiomyocyte death.

FIGURE 3.

Overexpression of ARIA enhances apoptosis in rat neonatal cardiomyocytes. A, isolated rat neonatal cardiomyocytes were transfected with GFP. Immunocytochemistry for GFP and α-actinin and Hoechst staining for nuclei were shown. Bar = 20 μm. B, isolated rat neonatal cardiomyocytes were transfected with either GFP or ARIA-FLAG. Cells were then treated with 50 μm hydrogen peroxide for 12 h. GFP or ARIA-FLAG and Hoechst staining for nuclei were detected under fluorescence microscopy. Apoptotic cells were detected as TUNEL-positive cells. Cells transfected with either GFP or ARIA were analyzed for apoptosis as indicated by arrows. Bar = 20 μm. C, the percentage of apoptotic cells was quantified in rat neonatal cardiomyocytes transfected with either GFP or ARIA-FLAG (n = 4). *, p < 0.05 versus control cells transfected with GFP. D, cells were treated with LY294002 to inhibit the PI3K and then stimulated with 50 μm hydrogen peroxide for 12 h. The percentage of apoptotic cells was quantified in rat neonatal cardiomyocytes transfected with either GFP or ARIA-FLAG (n = 4).

Loss of ARIA Enhances the Cardiac PI3K/Akt Signaling and Ameliorates the DOX-induced Cardiomyopathy in Vivo

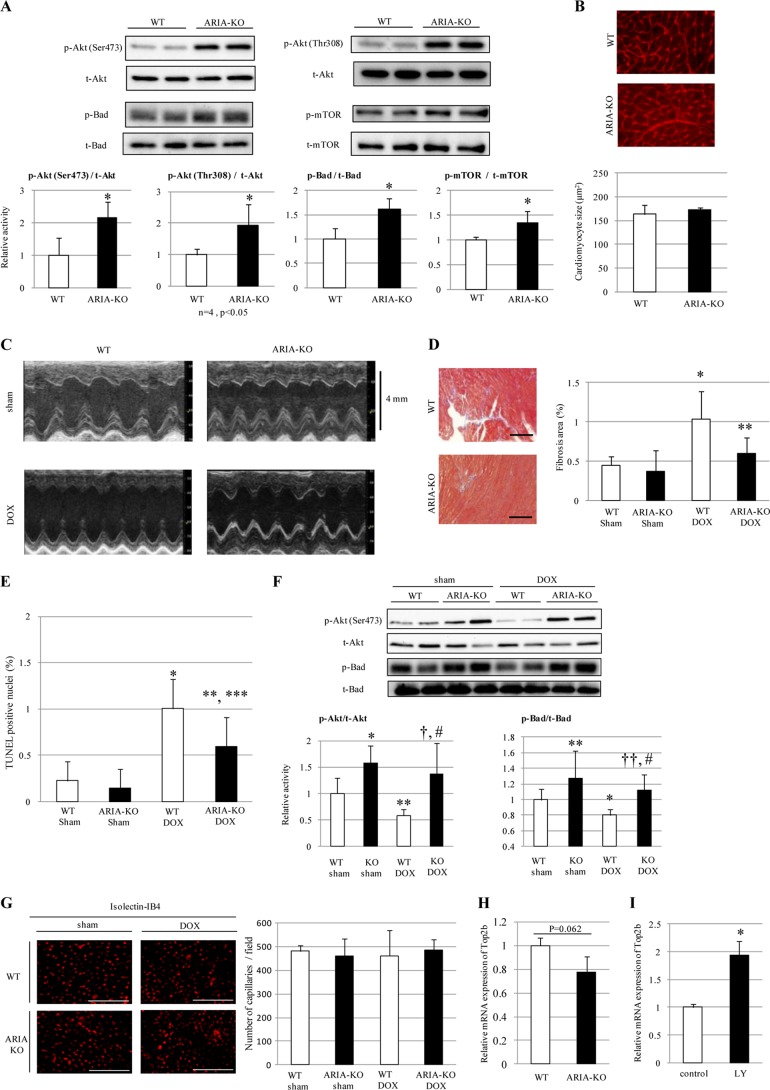

Consistent with the data above, genetic deletion of ARIA caused a significant increase in the phosphorylation of Akt, Bad, and mTOR in the heart in vivo (Fig. 4A). There was no significant change in the heart weight and size between ARIA−/− and wild type (WT) mice (Table 2 and Fig. 4B). We next analyzed whether ARIA-mediated modification of cardiac PI3K/Akt signaling plays a role in the pathophysiology of myocardial death and heart failure in vivo by using DOX-induced cardiomyopathy model.

FIGURE 4.

ARIA regulates the cardiac PI3K/Akt signaling and modifies the progression of DOX-induced cardiomyopathy. A, phosphorylation of Akt, Bad, and mTOR in the hearts of WT or ARIA-KO mice (n = 5). *, p < 0.05 versus WT mice. B, cardiomyocyte size was evaluated by staining the heart sections with wheat germ agglutinin (n = 5). Bar = 50 μm. C, representative M-mode images of echocardiograms in sham- or DOX-treated WT or ARIA-KO mice. D, cardiac fibrosis was evaluated by the Masson's trichrome staining (n = 6). *, p < 0.05 versus sham-treated WT mice. **, p < 0.01 versus DOX-treated WT mice. Bar = 100 μm. E, cardiomyocyte apoptosis was evaluated by TUNEL staining (n = 5). *, p < 0.01 versus sham-treated WT mice. **, p < 0.01 versus sham-treated KO mice. ***, p < 0.05 versus DOX-treated WT mice. F, phosphorylation of Akt and Bad in the hearts of WT or ARIA-KO mice on either sham or DOX treatment (n = 6). *, p < 0.01 versus sham-treated WT mice. **, p < 0.05 versus sham-treated WT mice. †, p < 0.01 versus DOX-treated WT mice. ††, p < 0.05 versus DOX-treated WT mice. #, not significant versus sham-treated KO mice. G, capillary density was assessed by isolectin IB4 staining of the heart sections (n = 4). Bar = 100 μm. H, expression of Top2b mRNA was assessed by quantitative PCR in the hearts of WT or ARIA-KO mice (n = 4; p = 0.062 versus WT mice). I, expression of Top2b mRNA was assessed by quantitative PCR in rat neonatal cardiomyocytes treated with either vehicle (control) or PI3K inhibitor LY294002 (LY). n = 4. *, p < 0.05 versus control.

TABLE 2.

Heart weight of WT or ARIA-deficient mice

Data are heart weight (HW) of WT or ARIA-deficient (ARIA-KO) mice at the age of 15 weeks old. BW, body weight; LVW, left ventricular weight; TL, tibia length.

| WT (n = 7) | ARIA-KO (n = 7) | |

|---|---|---|

| Heart weight (mg) | 112 ± 5.7 | 114 ± 17 |

| LV weight (mg) | 85.3 ± 5.5 | 85.4 ± 12 |

| Body weight (g) | 26.6 ± 1.1 | 27.6 ± 2.8 |

| Tibial length (mm) | 17.3 ± 0.25 | 17.1 ± 0.46 |

| HW/BW (mg/g) | 4.20 ± 0.16 | 4.12 ± 0.37 |

| LVW/BW (mg/g) | 3.20 ± 0.20 | 3.09 ± 0.31 |

| HW/TL (mg/mm) | 6.47 ± 0.29 | 6.67 ± 1.0 |

| LVW/TL (mg/mm) | 4.93 ± 0.28 | 5.00 ± 0.73 |

Treatment with DOX induced a significant cardiac dysfunction accompanied by the ventricular wall thinning in WT mice (Table 3 and Fig. 4C). In contrast, ARIA−/− mice exhibited no cardiac dysfunction, and wall thinning was ameliorated compared with WT mice after DOX treatment (Table 3 and Fig. 4C). Consistent with these findings, cardiomyocyte apoptosis was significantly reduced, and cardiac fibrosis was attenuated in ARIA−/− mice compared with DOX-treated WT mice (Fig. 4, D and E). In addition, the phosphorylation of Akt and Bad significantly decreased in the hearts of DOX-treated WT mice, but this was unchanged in the hearts of ARIA−/− mice even after DOX treatment (Fig. 4F). Because ARIA deletion enhances ischemia-induced angiogenesis (25), we investigated the blood vessel density in the hearts of both groups of mice. There was no difference in the vessel density in the hearts between WT and ARIA−/− mice before or after DOX treatment (Fig. 4G), suggesting that the loss of ARIA protects the hearts from DOX-induced cardiomyopathy independent of endothelial angiogenic capacity.

TABLE 3.

Echocardiographic data of WT and ARIA-deficient (ARIA-KO) mice on either sham or DOX treatment

FS, fractional shortening; IVST, interventricular septal thickness; LVPW, left ventricular posterior wall thickness. n = 8 each.

| LVDd | LVDs | FS | IVST | LVPW | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mm | mm | % | mm | mm | |

| WT sham | 3.84 ± 0.27 | 2.58 ± 0.18 | 32.7 ± 1.2 | 0.69 ± 0.031 | 0.68 ± 0.043 |

| ARIA-KO sham | 3.63 ± 0.32 | 2.39 ± 0.33 | 34.4 ± 3.9 | 0.71 ± 0.055 | 0.69 ± 0.027 |

| WT DOX | 4.02 ± 0.17 | 3.00 ± 0.31a | 25.4 ± 5.5a | 0.62 ± 0.036a | 0.60 ± 0.029a |

| ARIA-KO DOX | 3.76 ± 0.15b | 2.57 ± 0.25c | 31.5 ± 5.3c | 0.65 ± 0.022b,d | 0.64 ± 0.039c,e |

a p < 0.01 versus WT sham.

b p < 0.05 versus WT DOX.

c p < 0.01 versus WT DOX.

d p < 0.05 versus KO sham.

e p < 0.01 versus KO sham.

Recently the crucial role of Top2b, which encodes topoisomerase-IIβ, in the DOX-induced cardiomyopathy has been reported (11). DOX binds both DNA and Top2β, and Top2β-DOX-DNA ternary cleavage complex can induce DNA double-strand breaking, leading to cell death (11). We, therefore, examined the Top2b expression in the hearts of WT and ARIA−/− mice. Top2b expression tended to decrease in the hearts of ARIA−/− mice compared with WT mice (Fig. 4H). Moreover, we found that inhibition of PI3K/Akt signaling significantly enhanced Top2b expression in rat neonatal cardiomyocytes (Fig. 4I). These data suggest that PI3K/Akt signaling may protect cardiomyocytes from DOX-induced cell death partly by reducing the Top2b expression.

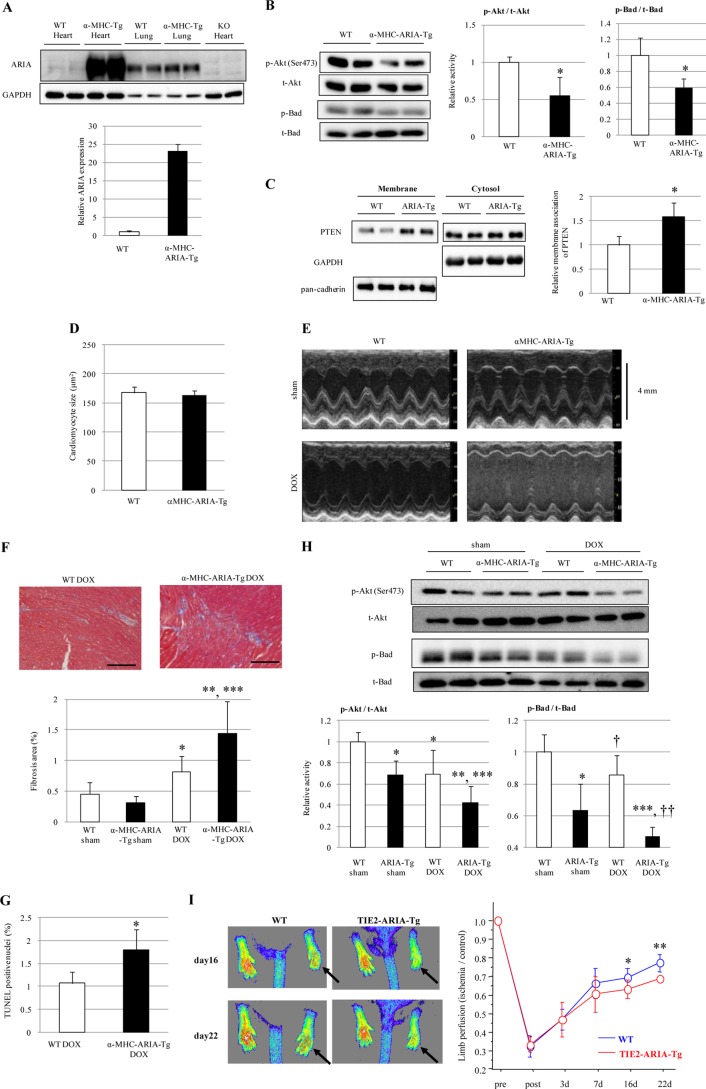

Targeted Activation of ARIA in Cardiomyocyte Attenuates the Cardiac PI3K/Akt Signaling

To confirm the role of ARIA in the heart, we generated mice with targeted activation of ARIA in cardiomyocyte (αMHC-ARIA-Tg). Overexpression of ARIA was detected in the heart but not in the lungs of αMHC-ARIA-Tg mice (Fig. 5A). In contrast to ARIA−/− mice, αMHC-ARIA-Tg mice showed a significant reduction in the phosphorylation of cardiac Akt and Bad, which was associated with an increase in membrane-associated PTEN in the heart (Fig. 5, B and C). The size and weight of the heart were not different between WT and αMHC-ARIA-Tg mice (Table 4 and Fig. 5D). However, compared with WT mice after DOX treatment, αMHC-ARIA-Tg mice exhibited deteriorated cardiac dysfunction and worsened ventricular wall thinning, which were accompanied by enhanced cardiomyocyte apoptosis and cardiac fibrosis (Table 5 and Fig. 5, E–G). Moreover, the DOX-mediated reduction in Akt and Bad phosphorylation was exacerbated in the hearts of αMHC-ARIA-Tg mice compared with WT mice (Fig. 5H).

FIGURE 5.

Targeted activation of ARIA in cardiomyocyte exacerbates the DOX-induced cardiomyopathy. A, immunoblotting for ARIA in the heart or lungs of WT, αMHC-ARIA-Tg, or ARIA-KO mice. B, phosphorylation of Akt and Bad in the hearts of WT or αMHC-ARIA-Tg mice (n = 6). *, p < 0.05 versus WT. C, PTEN expression in membrane or cytosolic fractions of the hearts isolated from WT or αMHC-ARIA-Tg mice (n = 4). *, p < 0.05 versus WT mice. D, cardiomyocyte size was evaluated in the hearts of WT or αMHC-ARIA-Tg mice (n = 5). E, representative M-mode images of echocardiogram in sham- or DOX-treated WT or αMHC-ARIA-Tg mice. F, cardiac fibrosis was evaluated by Masson's trichrome staining (n = 6). *, p < 0.05 versus sham-treated WT mice. **, p < 0.01 versus sham-treated αMHC-ARIA-Tg mice. ***, p < 0.01 versus DOX-treated WT mice. Bar = 100 μm. G, cardiomyocyte apoptosis was evaluated by TUNEL staining (n = 5). *, p < 0.05 versus DOX-treated WT mice. H, phosphorylation of Akt and Bad in the hearts of WT or αMHC-ARIA-Tg mice on either sham or DOX treatment (n = 6). *, p < 0.01 versus sham-treated WT mice. **, p < 0.01 versus sham-treated αMHC-ARIA-Tg mice. ***, p < 0.01 versus DOX-treated WT mice. †, p < 0.05 versus sham-treated WT mice. ††, p < 0.05 versus sham-treated αMHC-ARIA-Tg mice. I, WT or TIE2-ARIA-Tg mice at 12 weeks of age underwent hind limb ischemia. Blood flow was analyzed by laser Doppler at the indicated time points (n = 7–9). Arrows indicate the ischemic limbs. *, p < 0.05 and **, p < 0.001 versus WT mice.

TABLE 4.

Heart weight of WT or αMHC-ARIA-Tg mice

Data are the heart weight (HW) of WT or αMHC-ARIA-Tg mice at the age of 15 weeks old. BW, body weight; TL, tibia length; LV, left ventricular; LVW, left ventricular weight.

| WT (n = 7) | αMHC-ARIA-Tg (n = 7) | |

|---|---|---|

| Heart weight (mg) | 110 ± 17 | 109 ± 7.3 |

| LV weight (mg) | 84.1 ± 13 | 83.6 ± 0.2 |

| Body weight (g) | 26.8 ± 1.6 | 25.9 ± 1.4 |

| Tibial length (mm) | 16.7 ± 0.35 | 16.8 ± 0.24 |

| HW/BW (mg/g) | 4.07 ± 0.44 | 4.24 ± 0.40 |

| LVW/BW (mg/g) | 3.12 ± 0.35 | 3.24 ± 0.33 |

| HW/TL (mg/mm) | 6.56 ± 1.0 | 6.52 ± 0.49 |

| LVW/TL (mg/mm) | 5.03 ± 0.78 | 5.00 ± 0.41 |

TABLE 5.

Echocardiographic data of WT and αMHC-ARIA-Tg mice on either sham- or DOX-treatment

FS, fractional shortening; IVST, interventricular septal thickness; LVPW, left ventricular posterior wall thickness. n = 8 each.

| LVDd | LVDs | FS | IVST | LVPW | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mm | mm | % | mm | mm | |

| WT sham | 3.83 ± 0.34 | 2.59 ± 0.26 | 32.3 ± 3.6 | 0.69 ± 0.032 | 0.69 ± 0.043 |

| αMHC-ARIA-Tg sham | 3.84 ± 0.13 | 2.65 ± 0.13 | 31.2 ± 1.8 | 0.69 ± 0.041 | 0.70 ± 0.053 |

| WT DOX | 4.05 ± 0.31 | 3.01 ± 0.27a | 25.7 ± 2.8a | 0.63 ± 0.036a | 0.61 ± 0.041a |

| αMHC-ARIA-Tg DOX | 4.01 ± 0.21 | 3.14 ± 0.19b | 21.7 ± 1.5b,c | 0.60 ± 0.025b,d | 0.58 ± 0.020b.d |

a p < 0.01 versus WT sham.

b p < 0.01 versus αMHC-ARIA-Tg sham.

c p < 0.01 versus WT DOX.

d p < 0.05 versus WT DOX.

In addition, we explored whether EC-specific overexpression of ARIA under the control of the Tie2 promoter (Tie2-ARIA-Tg) affected cardiac function. Targeted activation of ARIA in EC significantly reduced the ischemia-induced neovascularization, which was assessed using the hind-limb ischemia model (Fig. 5I). However, DOX-induced cardiac dysfunction was similar between WT and Tie2-ARIA-Tg mice (Table 6). These data suggest that ARIA in cardiomyocyte but not in EC regulates cardiac function during pathological stress.

TABLE 6.

Echocardiographic data of WT and Tie2-ARIA-Tg mice on either sham or DOX treatment

FS, fractional shortening; IVST, interventricular septal thickness; LVPW, left ventricular posterior wall thickness. n = 5 each.

| LVDd | LVDs | FS | IVST | LVPW | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mm | mm | % | mm | mm | |

| WT sham | 3.87 ± 0.24 | 2.53 ± 0.33 | 34.8 ± 5.1 | 0.72 ± 0.041 | 0.70 ± 0.054 |

| Tie2-ARIA-Tg sham | 3.76 ± 0.33 | 2.50 ± 0.35 | 33.7 ± 3.9 | 0.70 ± 0.059 | 0.70 ± 0.032 |

| WT DOX | 4.00 ± 0.21 | 2.95 ± 0.31a | 26.3 ± 4.2a | 0.61 ± 0.026a | 0.61 ± 0.025a |

| Tie2-ARIA-Tg DOX | 3.94 ± 0.24 | 2.90 ± 0.19b | 26.2 ± 1.3b,d | 0.60 ± 0.029c,d | 0.62 ± 0.046c,d |

a p < 0.01 versus WT sham.

b p < 0.05 versus Tie2-ARIA-Tg sham.

c p < 0.01 versus Tie2-ARIA-Tg sham.

d Not significant versus WT DOX.

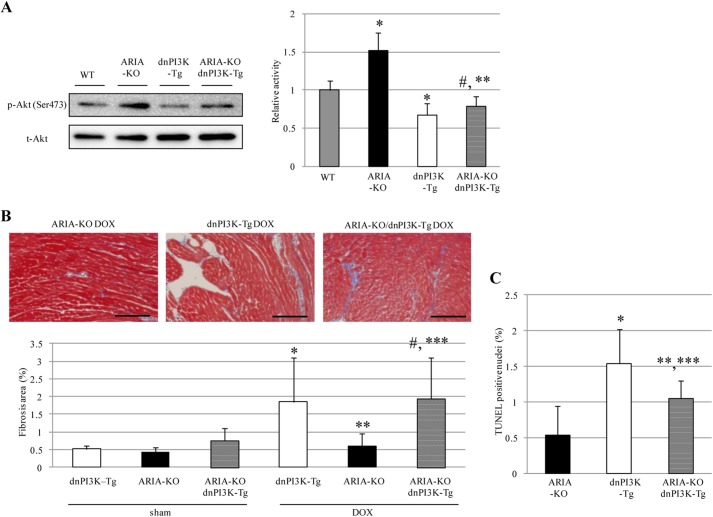

Inhibition of Cardiac PI3K Abolished the Cardioprotective Effects of ARIA Deletion

To further investigate whether the cardioprotective effects of ARIA deletion were because of enhanced cardiac PI3K/Akt signaling, we generated ARIA−/− mice with the targeted expression of dominant negative PI3K (p110α) in cardiomyocytes by crossing the ARIA−/− mice with αMHC-dnPI3K-Tg mice (32, 33). Suppressing PI3K signaling in cardiomyocytes completely abolished the enhanced phosphorylation of Akt observed in the hearts of ARIA−/− mice (Fig. 6A). In accordance with these findings, the cardioprotective effects of ARIA deletion also disappeared in the presence of the dnPI3K in cardiomyocytes. ARIA−/−/αMHC-dnPI3K-Tg mice exhibited cardiac dysfunction, ventricular wall thinning, and cardiac fibrosis comparable with WT mice after DOX treatment (Table 7 and Fig. 6B). In addition, reduced cardiomyocyte death in DOX-treated ARIA−/− mice was partially abrogated by repressing cardiac PI3K (Fig. 6C). ARIA deletion, therefore, protects the heart from DOX-induced cardiomyopathy by enhancing PI3K/Akt signaling in cardiomyocytes. Taken together, our data revealed a previously undescribed ARIA-mediated regulation of cardiac PI3K/Akt signaling and its significant role in the determination of cardiomyocyte death and the pathophysiology of stress-induced heart failure in vivo.

FIGURE 6.

Repressing cardiac PI3K abolished the cardio-protective effects of ARIA deletion. A, phosphorylation of Akt in the hearts of WT, ARIA-KO, dnPI3K-Tg, and ARIA-KO/dnPI3K-Tg mice (n = 8). *, p < 0.01 versus WT mice. **, p < 0.01 versus ARIA-KO mice. #, not significant versus dnPI3K-Tg mice. B, cardiac fibrosis was evaluated by Masson's trichrome staining (n = 5–6). *, p < 0.01 versus sham-treated dnPI3K-Tg mice. **, p < 0.01 versus DOX-treated dnPI3K-Tg mice. ***, p < 0.01 versus DOX-treated ARIA-KO mice. #, not significant versus DOX-treated dnPI3K-Tg mice. Bar = 100 μm. C, cardiomyocyte apoptosis was evaluated by TUNEL staining (n = 5). *, p < 0.01 versus ARIA-KO mice. **, p < 0.05 versus ARIA-KO mice. ***, p < 0.05 versus dnPI3K-Tg mice.

TABLE 7.

Echocardiographic data of dnPI3K-Tg, ARIA-KO, and dnPI3K-Tg/ARIA-KO mice on either sham or DOX treatment

FS, fractional shortening; IVST, interventricular septal thickness; LVPW, left ventricular posterior wall thickness. n = 5–6 each.

| LVDd | LVDs | FS | IVST | LVPW | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mm | mm | % | mm | mm | |

| dnPI3K-Tg sham | 3.82 ± 0.25 | 2.63 ± 0.18 | 31.1 ± 1.9 | 0.64 ± 0.021 | 0.64 ± 0.033 |

| ARIA-KO sham | 3.68 ± 0.18 | 2.50 ± 0.16 | 32.1 ± 2.4 | 0.70 ± 0.048 | 0.70 ± 0.036 |

| dnPI3K-Tg/ARIA-KO sham | 3.71 ± 0.23 | 2.57 ± 0.16 | 30.8 ± 0.88 | 0.67 ± 0.073 | 0.66 ± 0.018 |

| dnPI3K-Tg DOX | 3.92 ± 0.18 | 3.10 ± 0.19a,b | 21.0 ± 1.7a,b | 0.57 ± 0.055bc | 0.58 ± 0.050b,c |

| ARIA-KO DOX | 3.59 ± 0.24 | 2.51 ± 0.28 | 30.3 ± 4.5 | 0.65 ± 0.020 | 0.67 ± 0.007 |

| dnPI3K-Tg/ARIA-KO DOX | 3.86 ± 0.35 | 2.95 ± 0.29b,d,e | 23.7 ± 2.7b,d,e | 0.56 ± 0.067b,d,e | 0.58 ± 0.087b,d,e |

a p < 0.01 versus dnPI3K-Tg sham

b p < 0.01 versus ARIA-KO DOX

c p < 0.05 versus dnPI3K-Tg sham.

d p < 0.01 versus dnPI3K-Tg/ARIA-KO sham.

e Not significant versus dnPI3K-Tg DOX.

DISCUSSION

PI3K/Akt is a critical signaling pathway involved in a broad range of biological processes. One of the most important roles of this pathway is determining the cell fate, i.e. death or survival (18). Programmed cell death plays a crucial role in maintaining the tissue homeostasis by eliminating damaged or unnecessary cells without inducing local inflammation (34). However, excessive cellular apoptosis under pathological conditions can cause an intolerable loss of cells, leading to organ dysfunction. The heart is particularly sensitive to the loss of cardiomyocytes, and the death of very few myocytes could cause severe cardiac dysfunction (13). The inhibition of cardiomyocyte death has been shown to ameliorate the cardiac dysfunction in various stress-induced heart failure models such as ischemia reperfusion, pressure overload, and DOX-induced cardiomyopathy (19, 20, 35–37). Cardiac PI3K/Akt signaling is, therefore, a promising target for the treatment or prevention of heart failure due to various etiologies.

In the current study we identified significant expression of ARIA in cardiomyocytes and demonstrated for the first time that ARIA provides fine-tuning of cardiac PI3K/Akt signaling both in vitro and in vivo. Genetic deletion of ARIA caused an ∼2-fold increase in Akt phosphorylation. In contrast, overexpression of ARIA caused an ∼50% reduction in Akt phosphorylation in the heart compared with WT mice by altering the levels of membrane-associated PTEN. These moderate changes in Akt activity were sufficient to modify the susceptibility of cardiomyocytes to apoptosis but did not affect the size and weight of the heart.

PI3K/Akt signaling plays a crucial role in the determination of organ size, and therefore, modifying PI3K activity in cardiomyocytes could cause changes in the heart size and weight (4, 32, 38). Expression of constitutive active Akt in cardiomyocyte also induced ventricular hypertrophy (39). However, Akt was hyperactivated in this model, with ∼80-fold higher activity than in WT mice. In contrast, the expression of kinase-deficient Akt in cardiomyocytes caused an ∼50% reduction in Akt activity and did not affect the size and weight of the heart (39), consistent with our observation in αMHC-ARIA-Tg mice. Thus, more robust activation or inactivation of cardiac PI3K/Akt signaling may be necessary to induce changes in the size and weight of the heart than the fine-tuning that ARIA could provide.

Because ARIA modifies PI3K signaling by regulating PTEN function, both class IA and IB PI3K would be affected in the heart of ARIA−/− mice. However, the expression of dnPI3K (p110α) in cardiomyocytes was sufficient to abolish the cardioprotective effects of ARIA deletion, indicating that the reduced cardiomyocyte death observed in ARIA−/− mice can largely be attributed to class IA PI3K (p110α). This would be partially because cardioprotective proteins such as IGF-1 and neuregulin-1 predominantly activate receptor tyrosine kinases that subsequently activate class IA PI3K (40). Nevertheless, class IB PI3K may play a minor role in the cardioprotective effects of ARIA deletion.

ARIA expression is not restricted to cardiomyocytes because we observed high levels of expression in EC. It is, therefore, possible that the loss of ARIA in noncardiomyocytes contributes to the cardioprotective effects of ARIA deletion. However, we confirmed that the blood vessel density in the heart was not different between WT and ARIA−/− mice either before or after DOX treatment. Moreover, cardiomyocyte-specific expression of dnPI3K completely abolished the cardioprotective effects of ARIA deletion, and cardiomyocyte, but not endothelial cell-specific overexpression of ARIA showed a reversed phenotype compared with ARIA−/− mice with regard to DOX-induced cardiomyopathy. Combined with the in vitro data using H9c2/ARIA cells, these data confirm that ARIA determines the susceptibility of myocardial cells to apoptosis in a cell autonomous fashion and, therefore, plays a significant role in the regulation of cardiac function.

We, therefore, identified that ARIA is a novel regulator of cardiac PI3K/Akt signaling. Based on the cardioprotective effects observed in ARIA−/− mice, the inhibition of ARIA may be a fascinating approach to prevent and/or treat myocardial cell death and heart failure in response to pathological stress. Because of its unique role in PTEN function and its characteristic expression pattern, the inhibition of ARIA could modify the PTEN/PI3K pathway in specific cells and tissues such as cardiomyocytes and the heart. However, caution is required because inhibiting ARIA in EC would enhance angiogenesis, which may accelerate the growth of pre-existent tumors. In addition, PTEN is one of the most important tumor suppressor genes, and its systemic loss caused increased susceptibility to cancer (41). Additional studies, particularly investigating whether ARIA may affect systemic oncogenicity, are certainly required before ARIA could be considered as a therapeutic target.

Acknowledgment

We thank Dr. Tetsuo Shioi (Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, Kyoto University, Japan) for providing the αMHC-dnPI3K-Tg mice.

This work was supported by Grants-in-aid for Scientific Research (C: KAKENHI-23591107) and for Challenging Exploratory Research (KAKENHI-23659423) and a research grant from Takeda Science Foundation.

- mTOR

- mammalian target of rapamycin

- DOX

- doxorubicin

- ARIA

- apoptosis regulator through modulating IAP expression

- EC

- endothelial cell

- Tg

- transgenic

- dn-

- dominant negative

- LVDd

- left ventricular end-diastolic, dimension

- LVDs

- left ventricular end-systolic dimension.

REFERENCES

- 1. Kishimoto H., Hamada K., Saunders M., Backman S., Sasaki T., Nakano T., Mak T. W., Suzuki A. (2003) Physiological functions of Pten in mouse tissues. Cell Struct. Funct. 28, 11–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Oudit G. Y., Sun H., Kerfant B. G., Crackower M. A., Penninger J. M., Backx P. H. (2004) The role of phosphoinositide 3-kinase and PTEN in cardiovascular physiology and disease. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 37, 449–471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Oudit G. Y., Penninger J. M. (2009) Cardiac regulation by phosphoinositide 3-kinases and PTEN. Cardiovasc. Res. 82, 250–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Crackower M. A., Oudit G. Y., Kozieradzki I., Sarao R., Sun H., Sasaki T., Hirsch E., Suzuki A., Shioi T., Irie-Sasaki J., Sah R., Cheng H. Y., Rybin V. O., Lembo G., Fratta L., Oliveira-dos-Santos A. J., Benovic J. L., Kahn C. R., Izumo S., Steinberg S. F., Wymann M. P., Backx P. H., Penninger J. M. (2002) Regulation of myocardial contractility and cell size by distinct PI3K-PTEN signaling pathways. Cell 110, 737–749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Morello F., Perino A., Hirsch E. (2009) Phosphoinositide 3-kinase signalling in the vascular system. Cardiovasc. Res. 82, 261–271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Shiojima I., Walsh K. (2002) Role of Akt signaling in vascular homeostasis and angiogenesis. Circ. Res. 90, 1243–1250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Datta S. R., Dudek H., Tao X., Masters S., Fu H., Gotoh Y., Greenberg M. E. (1997) Akt phosphorylation of BAD couples survival signals to the cell-intrinsic death machinery. Cell 91, 231–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Salmena L., Carracedo A., Pandolfi P. P. (2008) Tenets of PTEN tumor suppression. Cell 133, 403–414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Singal P. K., Iliskovic N. (1998) Doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy. N. Engl. J. Med. 339, 900–905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Octavia Y., Tocchetti C. G., Gabrielson K. L., Janssens S., Crijns H. J., Moens A. L. (2012) Doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy. From molecular mechanisms to therapeutic strategies. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 52, 1213–1225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zhang S., Liu X., Bawa-Khalfe T., Lu L. S., Lyu Y. L., Liu L. F., Yeh E. T. (2012) Identification of the molecular basis of doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity. Nat. Med. 18, 1639–1642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chen B., Peng X., Pentassuglia L., Lim C. C., Sawyer D. B. (2007) Molecular and cellular mechanisms of anthracycline cardiotoxicity. Cardiovasc. Toxicol. 7, 114–121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wencker D., Chandra M., Nguyen K., Miao W., Garantziotis S., Factor S. M., Shirani J., Armstrong R. C., Kitsis R. N. (2003) A mechanistic role for cardiac myocyte apoptosis in heart failure. J. Clin. Invest. 111, 1497–1504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sprick M. R., Walczak H. (2004) The interplay between the Bcl-2 family and death receptor-mediated apoptosis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1644, 125–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Schultz D. R., Harrington W. J., Jr., (2003) Apoptosis. Programmed cell death at a molecular level. Semin. Arthritis. Rheum. 32, 345–369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pugazhenthi S., Nesterova A., Sable C., Heidenreich K. A., Boxer L. M., Heasley L. E., Reusch J. E. (2000) Akt/protein kinase B up-regulates Bcl-2 expression through cAMP-response element-binding protein. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 10761–10766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. del Peso L., González-García M., Page C., Herrera R., Nuñez G. (1997) Interleukin-3-induced phosphorylation of BAD through the protein kinase Akt. Science 278, 687–689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Luo H. R., Hattori H., Hossain M. A., Hester L., Huang Y., Lee-Kwon W., Donowitz M., Nagata E., Snyder S. H. (2003) Akt as a mediator of cell death. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 11712–11717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fan G. C., Zhou X., Wang X., Song G., Qian J., Nicolaou P., Chen G., Ren X., Kranias E. G. (2008) Heat shock protein 20 interacting with phosphorylated Akt reduces doxorubicin-triggered oxidative stress and cardiotoxicity. Circ. Res. 103, 1270–1279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Taniyama Y., Walsh K. (2002) Elevated myocardial Akt signaling ameliorates doxorubicin-induced congestive heart failure and promotes heart growth. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 34, 1241–1247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Crone S. A., Zhao Y. Y., Fan L., Gu Y., Minamisawa S., Liu Y., Peterson K. L., Chen J., Kahn R., Condorelli G., Ross J., Jr., Chien K. R., Lee K. F. (2002) ErbB2 is essential in the prevention of dilated cardiomyopathy. Nat. Med. 8, 459–465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. An T., Zhang Y., Huang Y., Zhang R., Yin S., Guo X., Wang Y., Zou C., Wei B., Lv R., Zhou Q., Zhang J. (2013) Neuregulin-1 protects against doxorubicin-induced apoptosis in cardiomyocytes through an Akt-dependent pathway. Physiol. Res. 62, 379–385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wu W., Lee W. L., Wu Y. Y., Chen D., Liu T. J., Jang A., Sharma P. M., Wang P. H. (2000) Expression of constitutively active phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase inhibits activation of caspase 3 and apoptosis of cardiac muscle cells. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 40113–40119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ikeda K., Nakano R., Uraoka M., Nakagawa Y., Koide M., Katsume A., Minamino K., Yamada E., Yamada H., Quertermous T., Matsubara H. (2009) Identification of ARIA regulating endothelial apoptosis and angiogenesis by modulating proteasomal degradation of cIAP-1 and cIAP-2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 8227–8232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Koide M., Ikeda K., Akakabe Y., Kitamura Y., Ueyama T., Matoba S., Yamada H., Okigaki M., Matsubara H. (2011) Apoptosis regulator through modulating IAP expression (ARIA) controls the PI3K/Akt pathway in endothelial and endothelial progenitor cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 9472–9477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ogata T., Ueyama T., Isodono K., Tagawa M., Takehara N., Kawashima T., Harada K., Takahashi T., Shioi T., Matsubara H., Oh H. (2008) MURC, a muscle-restricted coiled-coil protein that modulates the Rho/ROCK pathway, induces cardiac dysfunction and conduction disturbance. Mol. Cell. Biol. 28, 3424–3436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Armstrong L. J., Heath V. L., Sanderson S., Kaur S., Beesley J. F., Herbert J. M., Legg J. A., Poulsom R., Bicknell R. (2008) ECSM2, an endothelial specific filamin a binding protein that mediates chemotaxis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 28, 1640–1646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ma F., Zhang D., Yang H., Sun H., Wu W., Gan Y., Balducci J., Wei Y. Q., Zhao X., Huang Y. (2009) Endothelial cell-specific molecule 2 (ECSM2) modulates actin remodeling and epidermal growth factor receptor signaling. Genes. Cells 14, 281–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zha J., Harada H., Yang E., Jockel J., Korsmeyer S. J. (1996) Serine phosphorylation of death agonist BAD in response to survival factor results in binding to 14-3-3 not BCL-X(L). Cell 87, 619–628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Macdonald A., Campbell D. G., Toth R., McLauchlan H., Hastie C. J., Arthur J. S. (2006) Pim kinases phosphorylate multiple sites on Bad and promote 14-3-3 binding and dissociation from Bcl-XL. BMC Cell Biol. 7, 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hay N. (2005) The Akt-mTOR tango and its relevance to cancer. Cancer Cell 8, 179–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Shioi T., Kang P. M., Douglas P. S., Hampe J., Yballe C. M., Lawitts J., Cantley L. C., Izumo S. (2000) The conserved phosphoinositide 3-kinase pathway determines heart size in mice. EMBO J. 19, 2537–2548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. McMullen J. R., Shioi T., Zhang L., Tarnavski O., Sherwood M. C., Kang P. M., Izumo S. (2003) Phosphoinositide 3-kinase (p110α) plays a critical role for the induction of physiological, but not pathological, cardiac hypertrophy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 12355–12360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Henson P. M., Hume D. A. (2006) Apoptotic cell removal in development and tissue homeostasis. Trends Immunol. 27, 244–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Oshima Y., Ouchi N., Sato K., Izumiya Y., Pimentel D. R., Walsh K. (2008) Follistatin-like 1 is an Akt-regulated cardioprotective factor that is secreted by the heart. Circulation 117, 3099–3108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ruan H., Li J., Ren S., Gao J., Li G., Kim R., Wu H., Wang Y. (2009) Inducible and cardiac specific PTEN inactivation protects ischemia/reperfusion injury. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 46, 193–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lin R. C., Weeks K. L., Gao X. M., Williams R. B., Bernardo B. C., Kiriazis H., Matthews V. B., Woodcock E. A., Bouwman R. D., Mollica J. P., Speirs H. J., Dawes I. W., Daly R. J., Shioi T., Izumo S., Febbraio M. A., Du X. J., McMullen J. R. (2010) PI3K(p110α) protects against myocardial infarction-induced heart failure. dentification of PI3K-regulated miRNA and mRNA. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 30, 724–732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Condorelli G., Drusco A., Stassi G., Bellacosa A., Roncarati R., Iaccarino G., Russo M. A., Gu Y., Dalton N., Chung C., Latronico M. V., Napoli C., Sadoshima J., Croce C. M., Ross J., Jr., (2002) Akt induces enhanced myocardial contractility and cell size in vivo in transgenic mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 12333–12338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Shioi T., McMullen J. R., Kang P. M., Douglas P. S., Obata T., Franke T. F., Cantley L. C., Izumo S. (2002) Akt/protein kinase B promotes organ growth in transgenic mice. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 2799–2809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Katada T., Kurosu H., Okada T., Suzuki T., Tsujimoto N., Takasuga S., Kontani K., Hazeki O., Ui M. (1999) Synergistic activation of a family of phosphoinositide 3-kinase via G-protein coupled and tyrosine kinase-related receptors. Chem. Phys. Lipids. 98, 79–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Alimonti A., Carracedo A., Clohessy J. G., Trotman L. C., Nardella C., Egia A., Salmena L., Sampieri K., Haveman W. J., Brogi E., Richardson A. L., Zhang J., Pandolfi P. P. (2010) Subtle variations in Pten dose determine cancer susceptibility. Nat. Genet. 42, 454–458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]