Abstract

The links between disasters and violence either self-directed or interpersonal are now more recognized. Nevertheless, the amount of research is limited. This article discusses the underlying association of disasters and violence and it also outlines a systematic review of the literature from 1976 to 2011. Finally, it concludes and recommends particular approaches for further epidemiological research.

Keywords: Epidemiological studies, natural disasters, interpersonal violence, self-directed violence

INTRODUCTION

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines violence as: “The intentional use of physical force or power, threatened or actual, against oneself, another person or against a group or community, which either results in or has a high likelihood of resulting in, injury, death, psychological harm, maldevelopment or deprivation.”[1]

Based on this definition WHO splits violence into three broad categories, i.e., self-directed violence; interpersonal violence; and collective violence. Self-directed violence includes suicidal behavior (i.e., suicidal ideation, plans, attempted suicide, and suicide). Interpersonal violence by itself divides into two categories, i.e., family and intimate partner violence (e.g., child abuse, violence by an intimate partner and abuse of the elderly) and community violence (e.g., youth violence, rape or sexual assault by strangers and violence in institutional settings). Collective violence includes wars and armed conflicts within or between states, genocide, and terrorism.[2]

Collective violence as like as other types of violence is related to human distress and is disastrous, which is dealt with elsewhere.[3,4,5,6,7] Nonetheless, the results of a few recent studies[8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16] suggest that both self-directed violence and interpersonal violence might increase after natural disasters, e.g., earthquake, flood, tropical cyclones etc.

In the present article therefore, I am going to focus on the relation between violence and natural disasters by looking at the literature, and recommend more well-planned epidemiological studies. I begin with the underlying associations between natural disasters and violence.

NATURAL DISASTERS AND VIOLENCE: THE UNDERLYING ASSOCIATIONS

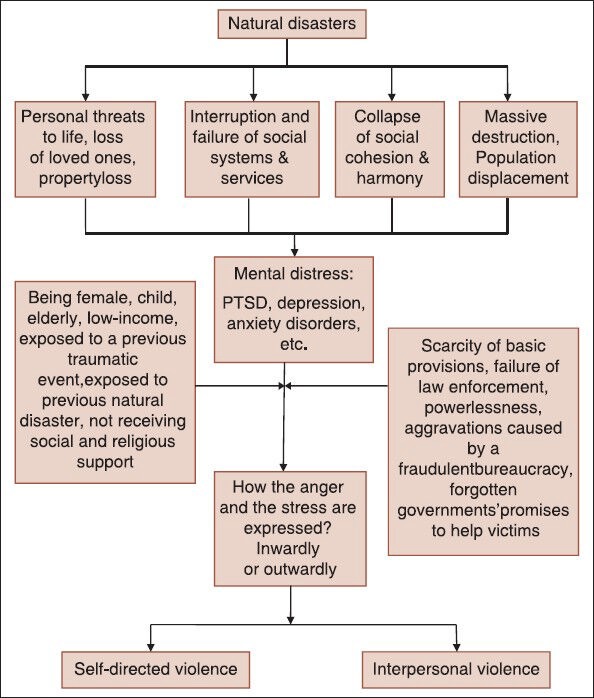

Natural disasters might increase the rate of violence both in the short and long-term, in a number of ways.[16] For instance, in the aftermath of a natural disaster mental distress among the affected population will increase. There is evidence, which suggests that between a third and half of all persons exposed to natural disasters will finally develop mental distress, e.g., post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, anxiety disorders, etc.[11]

Personal threats to life, loss of loved ones, property loss, immense destruction, breakdown of social security systems, collapse of social cohesion and harmony and so on, are the most important reasons behind this trend and diverse studies highlight that the effects of catastrophic disasters on mental health are larger than mild ones.[8,9,10,12,13,14,15].

Furthermore, due to the scarcity of basic provisions, failure of law enforcement, powerlessness, aggravation caused by a fraudulent bureaucracy and forgotten governments’ promises to help victims, etc. it would be possible that the semental distresses will develop into violence, either self-directed[13] or interpersonal.[16]

In the path of relation between being exposed to natural disaster and developing mental distress, which leads to one form of violence, there are also a number of other variables.[17] For example, it has been shown that women, children, elderly, low-income and those people who have been exposed to a previous traumatic event are more vulnerable to developing mental distress[18,19] or being a victim of violence in the aftermath of natural disasters.[16]

It is also vital to realize that being exposed to one natural disaster might amplify the adverse psychological outcomes of being exposed to subsequent natural disasters.[20] Furthermore, those people who received social[19] or religious[21,22] support were less vulnerable to developing such adverse psychological outcomes.

All the above discussions are depicted in Figure 1. The key point in this figure is that how the anger and the stress of those who exposed to natural disasters are expressed inwardly, i.e., self-directed or outwardly, i.e., interpersonal violence.

Figure 1.

The underlying associations between natural disasters and violence

SEARCH OF THE LITERATURE

I searched the literature using a well-known search engine, i.e., PubMed (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) from 1/1/1978 to 31/12/2011. Thirteen keywords were selected which included “flood,” “hurricane,” “drought,” “cyclone,” “tornado,” “volcanic eruption,” “earthquake,” “blizzard,” “tsunami,” “avalanche,” “famine,” “natural disaster,” and “violence.”

A search strategy was built applying advanced search capability of the search engine. Based on this search strategy, only those articles were retrieved that had one of the first 12 keywords plus the 13 keyword either in the title or the abstract. This strategy retrieved 70 articles.

The inclusion criteria as set out that only original article that explicitly dealt with violence after natural disasters and written in English was included. From 70 numbers of retrieved papers only a handful was original and explicitly dealt with violence after natural disasters.

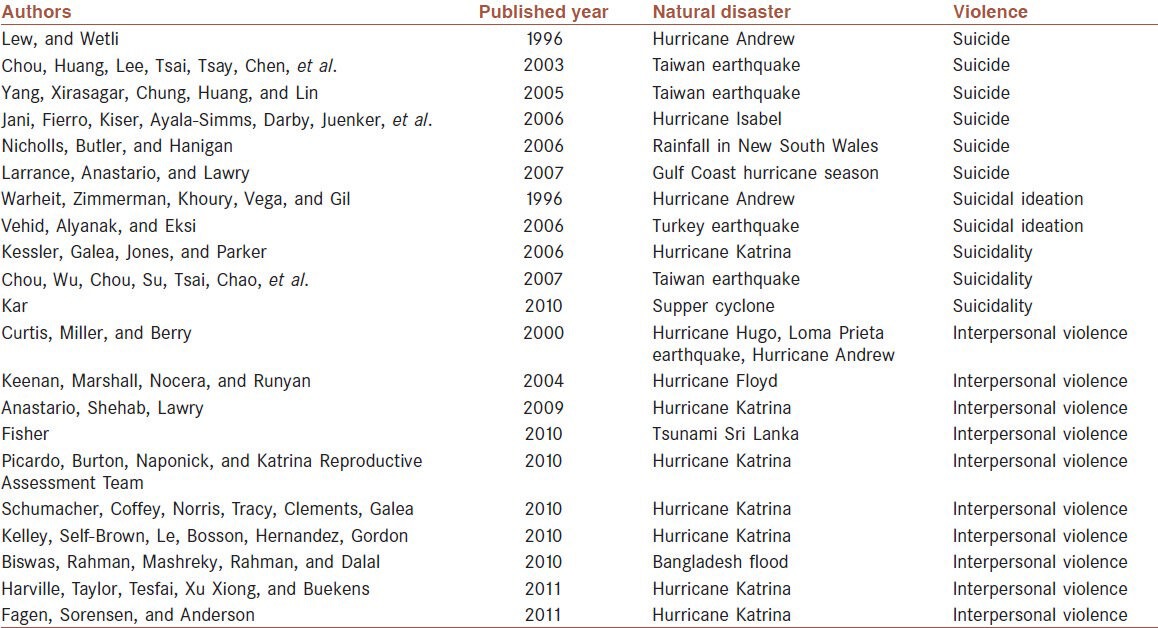

Therefore, in the next step, I also looked at the reference list of the retrieved papers and searched other search engines such as Scopus. Having carried out that, there was still a shortage of original research regarding these important topics and I have totally retrieved only 21 articles that met the inclusion criteria [Table 1]. Nevertheless, below are the results of these search strategies, which were summarized for self-directed and interpersonal violence, separately.

Table 1.

The details of 21 original articles that met the inclusion criteria

NATURAL DISASTERS AND SELF-DIRECTED VIOLENCE

Mental disorders are among the strongest risk factors for self-directed violence, i.e., suicidal behavior[23,24] and as it has been mentioned earlier, being exposed to natural disasters will increase the likelihood of developing mental disorders.[11] Therefore, a relation between being exposed to natural disasters and developing suicidal behavior would also be possible.[25]

The literature review highlights that there are only a few studies, which focus on this relationship and report that being exposed to a natural disaster such as hurricane, cyclone and earthquake, might increase the rates of suicide[26,27,28,29,30,31,32] or suicidality.[33,34,35,36,37] One of these studies[27] later retracted some of its initial findings due to errors in its analyses.[38]

The results of one study[35] have revealed that suicidal behavior might manifest years after a natural disaster, i.e., earthquake has occurred. This seems to be related to “the quarrels among families regarding sharing the financial burden of rebuilding the house, the poor control of mental disease owing to the disorganized health-care systems, the lack of social and financial support during the harsh rebuilding process, the powerlessness, and the frustrations caused by a corrupt bureaucracy,”[13] and not the shock of the disaster per se.

NATURAL DISASTERS AND INTERPERSONAL VIOLENCE

The literature review also highlight that there are only a few studies, which focus on the relation between being exposed to a natural disaster and the rates of interpersonal violence.[16] The results of these studies reveal that being exposed to natural disasters such as tsunami, hurricane, earthquake, and flood increases the violence against women and girls, e.g., rape and sexual abuse,[39,40,41] intimate partner violence,[32,42,43,44] child PTSD,[45] child abuse,[46,47] and inflicted traumatic brain injury.[48]

However, it should be noted that there is also one published study, which reported no significant variations in any of the measures of sexual violence toward women in the periods before and after a natural disaster, i.e., hurricane.[49]

Since in the aftermath of natural disasters women and children may be separated from their family, they are often at greater risk of being subject to interpersonal violence.[16] Therefore, in such situations proper attention should be paid to the needs of these vulnerable groups.

These include: Swift identification of separated children and reunification of them with their official guardians,[50] providing secure places for single women and girls[39] and providing proper health services, counseling, and legal support for the victims of such violence.[16,51]

CONCLUDING REMARKS

The relation between being exposed to natural disaster and being a victim of violence either self-directed or interpersonal is coming to light with recent studies. Natural disasters might increase the rate of violence both in the short and long-term by developing mental distress and anger. The key point is that how the exposed population reacts to these pressures either inwardly or outwardly.

Although, there is a scarcity of research in this area the potential threats of violence after natural disaster should not be neglected by the scientific community. Therefore, given the alarming increase of natural disasters during recent decades[52,53,54] it is time to design and conduct more methodological sound studies.[55] The chief aims of these studies are to understand how natural disasters form and/or change the pattern of violence within the community and to recommend the most useful structure of support services.

RECOMMENDING PARTICULAR APPROACHES FOR FURTHER EPIDEMIOLOGICAL RESEARCH

The following approaches could be recommended for further epidemiological research in this area:

The length of the study should be long enough to allow scientists to determine any possible relation between being exposed to natural disasters and being a victim of violence. However, it should be noted that although long-term follow-up is important it does not mean that one should overlooked the importance of getting in the field as fast as possible.

Further research should also take into account the type and the magnitude of natural disasters plus the effects of any possible moderating or confounding variables, e.g., age, sex, income, family and social supports, the degree of religiosity of the community, etc.

For comparison purposes, it is necessary to have access to the baseline data, i.e., the type and extent of violence in the community before the occurrence of natural disaster. This means that gathering information regarding the type and extent of violence should integrate in any surveillance systems around the world.

It worth emphasizing that having an efficient surveillance system for reporting violence is vital especially within developing worlds. Since evidence suggest that there is a high likelihood that different types of violence might be under-reported in such countries.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author would like to appreciate the helpful comments of Ian Enzer, Lesley Pocock and two anonymous referees on the earlier drafts of this article.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Geneva: World Health Organization; 1996. World Health Organization Global Consultation on Violence and Health. Violence: A Public Health Priority. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2002. World Health Organization. World Report on Violence and Health; pp. 197–8. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murray CJ, King G, Lopez AD, Tomijima N, Krug EG. Armed conflict as a public health problem. BMJ. 2002;324:346–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7333.346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Milio NR. When wars overwhelm welfare. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2007;61:274–5. doi: 10.1136/jech.2006.051607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sidel VW, Levy BS. War. In: Baslaugh S, editor. Encyclopedia of Epidemiology. Vol. 2. California: SAGE Publications, Inc; 2008. pp. 1091–3. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rezaeian M. War is an unjustifiable man-made disaster within the eastern Mediterranean region. Middle East J Fam Med. 2008;6:14–6. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rezaeian M. A review on the most important consequences of wars and armed conflicts. Middle East J Bus. 2009;4:7–9. [Google Scholar]

- 8.David D, Mellman TA, Mendoza LM, Kulick-Bell R, Ironson G, Schneiderman N. Psychiatric morbidity following Hurricane Andrew. J Trauma Stress. 1996;9:607–12. doi: 10.1007/BF02103669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Norris FH, Perilla JL, Riad JK, Kaniasty K, Lavizzo EA. Stability and change in stress, resources, and psychological distress following natural disaster: Findings from hurricane Andrew. Anxiety Stress Coping. 1999;12:363–96. doi: 10.1080/10615809908249317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Armenian HK, Morikawa M, Melkonian AK, Hovanesian AP, Haroutunian N, Saigh PA, et al. Loss as a determinant of PTSD in a cohort of adult survivors of the 1988 earthquake in Armenia: Implications for policy. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2000;102:58–64. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2000.102001058.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2001. World Health Organization. The World Health Report 2001 Mental Health: New Understanding, New Hope; p. 43. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goenjian AK, Molina L, Steinberg AM, Fairbanks LA, Alvarez ML, Goenjian HA, et al. Posttraumatic stress and depressive reactions among Nicaraguan adolescents after hurricane Mitch. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:788–94. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.5.788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lu TH. Earthquake and suicide: Bringing context back into disaster epidemiological studies. Int J Epidemiol. 2004;33:1406–9. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyh234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu HC, Chou P, Chou FH, Su CY, Tsai KY, Ou-Yang WC, et al. Survey of quality of life and related risk factors for a Taiwanese village population 3 years post-earthquake. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2006;40:355–61. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2006.01802.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kessler RC, Galea S, Jones RT, Parker HA Hurricane Katrina Community Advisory Group. Mentalillness and suicidality after Hurricane Katrina. Bull World Health Organ. 2006;84:930–9. doi: 10.2471/blt.06.033019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Health Organization. Interpersonal violence & disasters. [Last accessed 2008 Feb 15]. Available from: http://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/publications/violence/violence_disasters.pdf .

- 17.Shultz JM, Russell J, Espinel Z. Epidemiology of tropical cyclones: The dynamics of disaster, disease, and development. Epidemiol Rev. 2005;27:21–35. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxi011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Phifer JF, Kaniasty KZ, Norris FH. The impact of natural disaster on the health of older adults: A multiwave prospective study. J Health Soc Behav. 1988;29:65–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feng S, Tan H, Benjamin A, Wen S, Liu A, Zhou J, et al. Social support and posttraumatic stress disorder among flood victims in Hunan, China. Ann Epidemiol. 2007;17:827–33. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2007.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Salloum A, Carter P, Burch B, Garfinkel A, Overstreet S. Impact of exposure to community violence, Hurricane Katrina, and Hurricane Gustav on posttraumatic stress and depressive symptoms among school age children. Anxiety Stress Coping. 2011;24:27–42. doi: 10.1080/10615801003703193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koenig HG. Case discussion – Religion and coping with natural disaster. South Med J. 2007;100:954. doi: 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e3181454904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rezaeian M. The adverse psychological outcomes of natural disasters: How religion may help to disrupt the connection. J Pastoral Care Counsel. 2008;62:289–92. doi: 10.1177/154230500806200312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harris EC, Barraclough B. Suicide as an outcome for mental disorders. A meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 1997;170:205–28. doi: 10.1192/bjp.170.3.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Amos T, Appleby L. Suicide and deliberate self-harm. In: Appleby L, Forshaw D, Amos T, Barker H, editors. Postgraduate Psychiatry: Clinical and Scientific Foundations. London: Arnold; 2001. pp. 347–57. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rezaeian M. Epidemiology of suicide after natural disasters: A review on the literature and a methodological framework for future studies. Am J Disaster Med. 2008;3:52–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lew EO, Wetli CV. Mortality from Hurricane Andrew. J Forensic Sci. 1996;41:449–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krug EG, Kresnow M, Peddicord JP, Dahlberg LL, Powell KE, Crosby AE, et al. Suicide after natural disasters. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:373–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199802053380607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chou YJ, Huang N, Lee CH, Tsai SL, Tsay JH, Chen LS, et al. Suicides after the 1999 Taiwan earthquake. Int J Epidemiol. 2003;32:1007–14. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyg296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang CH, Xirasagar S, Chung HC, Huang YT, Lin HC. Suicide trends following the Taiwan earthquake of 1999: Empirical evidence and policy implications. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2005;112:442–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00603.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jani AA, Fierro M, Kiser S, Ayala-Simms V, Darby DH, Juenker S, et al. Hurricane Isabel-related mortality – Virginia, 2003. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2006;12:97–102. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200601000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nicholls N, Butler CD, Hanigan I. Inter-annual rainfall variations and suicide in New South Wales, Australia, 1964-2001. Int J Biometeorol. 2006;50:139–43. doi: 10.1007/s00484-005-0002-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Larrance R, Anastario M, Lawry L. Health status among internally displaced persons in Louisiana and Mississippi travel trailer parks. (601.e1-12).Ann Emerg Med. 2007;49:590–601. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Warheit GJ, Zimmerman RS, Khoury EL, Vega WA, Gil AG. Disaster related stresses, depressive signs and symptoms, and suicidal ideation among a multi-racial/ethnic sample of adolescents: A longitudinal analysis. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1996;37:435–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1996.tb01424.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vehid HE, Alyanak B, Eksi A. Suicide ideation after the 1999 earthquake in Marmara, Turkey. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2006;208:19–24. doi: 10.1620/tjem.208.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chou FH, Wu HC, Chou P, Su CY, Tsai KY, Chao SS, et al. Epidemiologic psychiatric studies on post-disaster impact among Chi-Chi earthquake survivors in Yu-Chi, Taiwan. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2007;61:370–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2007.01688.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sakauye KM, Streim JE, Kennedy GJ, Kirwin PD, Llorente MD, Schultz SK, et al. AAGP position statement: Disaster preparedness for older Americans: Critical issues for the preservation of mental health. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;17:916–24. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181b4bf20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kar N. Suicidality following a natural disaster. Am J Disaster Med. 2010;5:361–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Krug EG, Kresnow M, Peddicord JP, Dahlberg LL, Powell KE, Crosby AE, et al. Retraction: Suicide after natural disasters. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:148–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199901143400213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pittaway E, Bartolomei L, Rees S. Neglected issues and voices. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2007;19:69. doi: 10.1177/101053950701901S11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fisher S. Violence against women and natural disasters: Findings from post-tsunami Sri Lanka. Violence Against Women. 2010;16:902–18. doi: 10.1177/1077801210377649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Picardo CW, Burton S, Naponick J Katrina Reproductive Assessment Team. Physically and sexually violent experiences of reproductive-aged women displaced by Hurricane Katrina. (284-8).J La State Med Soc. 2010;162:282. 290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Anastario M, Shehab N, Lawry L. Increased gender-based violence among women internally displaced in Mississippi 2 years post-Hurricane Katrina. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2009;3:18–26. doi: 10.1097/DMP.0b013e3181979c32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schumacher JA, Coffey SF, Norris FH, Tracy M, Clements K, Galea S. Intimate partner violence and Hurricane Katrina: Predictors and associated mental health outcomes. Violence Vict. 2010;25:588–603. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.25.5.588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Harville EW, Taylor CA, Tesfai H, Xu Xiong, Buekens P. Experience of Hurricane Katrina and reported intimate partner violence. J Interpers Violence. 2011;26:833–45. doi: 10.1177/0886260510365861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kelley ML, Self-Brown S, Le B, Bosson JV, Hernandez BC, Gordon AT. Predicting posttraumatic stress symptoms in children following Hurricane Katrina: A prospective analysis of the effect of parental distress and parenting practices. J Trauma Stress. 2010;23:582–90. doi: 10.1002/jts.20573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Curtis T, Miller BC, Berry EH. Changes in reports and incidence of child abuse following natural disasters. Child Abuse Negl. 2000;24:1151–62. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(00)00176-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Biswas A, Rahman A, Mashreky S, Rahman F, Dalal K. Unintentional injuries and parental violence against children during flood: A study in rural Bangladesh. Rural Remote Health. 2010;10:1199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Keenan HT, Marshall SW, Nocera MA, Runyan DK. Increased incidence of inflicted traumatic brain injury in children after a natural disaster. Am J Prev Med. 2004;26:189–93. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2003.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fagen JL, Sorensen W, Anderson PB. Why not the University of New Orleans? Social disorganization and sexual violence among internally displaced women of Hurricane Katrina. J Community Health. 2011;36:721–7. doi: 10.1007/s10900-011-9365-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brandenburg MA, Watkins SM, Brandenburg KL, Schieche C. Operation Child-ID: Reunifying children with their legal guardians after Hurricane Katrina. Disasters. 2007;31:277–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7717.2007.01009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cohen JA, Jaycox LH, Walker DW, Mannarino AP, Langley AK, DuClos JL. Treating traumatized children after Hurricane Katrina: Project Fleur-de lis. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2009;12:55–64. doi: 10.1007/s10567-009-0039-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Noji EK. Disaster epidemiology. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 1996;14:289–300. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8627(05)70252-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bohannon J. Disasters: Searching for lessons from a bad year. Science. 2005;310:1883. doi: 10.1126/science.310.5756.1883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shaikh IA, Musani A. Emergency preparedness and humanitarian action: The research deficit. Eastern Mediterranean Region perspective. East Mediterr Health J. 2006;12:S54–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rezaeian M. Epidemiological approaches to disasters and emergencies within the middle east region. Middle East J Emerg Med. 2007;7:54–6. [Google Scholar]