Abstract

OBJECTIVE:

To evaluate the effect of blocking the angiotensin II AT-1 receptor by the systemic administration of candesartan on the expression of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 in the sclera and choroid of hypercholesterolemic rabbits.

METHODS:

New Zealand rabbits were divided into 3 groups, as follows: GI, which was fed a rabbit standard diet; GII, which was fed a hypercholesterolemic diet; and GIII, which received hypercholesterolemic diet plus candesartan. Samples of the rabbits' sclera and choroid were then studied by hematoxylin-eosin staining and histomorphometric and immunohistochemical analyses for intercellular adhesion molecule-1 expression.

RESULTS:

Histological analysis of hematoxylin- and eosin-stained sclera and choroid revealed that macrophages were rarely present in GI, and GII had significantly increased macrophage numbers compared to GIII. Moreover, in GII, the sclera and choroid morphometry showed a significant increase in thickness in comparison to GI and GIII. GIII presented a significant increase in thickness in relation to GI. Sclera and choroid immunohistochemical analysis for intercellular adhesion molecule-1 expression revealed a significant increase in immunoreactivity in GII in relation to GI and GIII. GIII showed a significant increase in immunoreactivity in relation to GI.

CONCLUSION:

Candesartan reduced the expression of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 and consequently macrophage accumulation in the sclera and choroid of hypercholesterolemic rabbits.

Keywords: Renin-Angiotensin System, Cholesterol, Cell Adhesion Molecules, Macrophages, Choroid, Sclera, Macular Degeneration

INTRODUCTION

Macrophages are the dominant cellular players in chronic inflammation and secrete cytokines, enzymes and growth factors that contribute to the development and progression of several pathologies. Thus, macrophages have become a very important therapeutic target. There is evidence that age-related macular degeneration (ARMD) and atherosclerosis share similar physiopathogenic mechanisms 1,2. ARMD is the main cause of irreversible blindness in older people and may lead to a loss of central vision due to choroid geographic atrophy or the formation of sub-retinal neovascularization. The cardiovascular complications, secondary to the atherosclerotic process, and the blindness induced by ARMD result in increased macrophage accumulations in the arterial wall and in the Bruch's membrane, respectively 3,4.

Intercellular Adhesion Molecule 1 (ICAM-1), also known as CD54, is a glycoprotein of the immunoglobulin super family. Similar to other adhesion molecules, ICAM-1 is distributed on endothelial cells and leukocytes and induces the recruitment of leukocytes to lesioned or inflamed tissues 5. In the human ocular globe, a greater concentration of this immunoglobulin has been found in the choriocapillaris of the macular region than in the peripheral region 6. This finding suggests that many immune cells, including macrophages, may be present in the macula. This finding also accounts for the greater formation of the subretinal neovascular membrane (wet ARMD) in this region.

In atherosclerosis, macrophages decrease atherosclerotic plaque formation 7. In ARMD, experimental studies have shown that the inhibition of macrophage functions improves the neovascular condition 8. Thus, drugs that inhibit the mobilization and/or adhesion of monocytes to the inflamed tissue may be effective not only for treating atherosclerosis, but also for preventing the development of ARMD. Additionally, previous studies have suggested that the activation of the renin-angiotensin system is related to the physiopathogenesis of ARMD and that the blockade of this system is related to its regression 9,10.

The objective of this study was to determine the effects of candesartan-mediated blockage of the angiotensin II AT-1 receptor on ICAM-1 expression and the accumulation of macrophages in the sclera and choroid of hypercholesterolemic rabbits.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimentation environment

The procedures described in this study were performed at the Surgical Technique Laboratory at Pontificia Universidade Católica do Paraná, Graduation, Curirtiba/PR (PUC-PR) and the Study Center of the Angelina Caron Hospital. The animals were kept in an animal facility (macroenvironment) on 12/12-hour light cycles, with air changes and room temperature controlled between 19 and 23°C. During the experimental period, the animals were fed water and standard Nuvital® rabbit chow (Nuvital, Colombo, Brazil) ad libitum.

Animals used and experiment design

In total, 33 white adult male rabbits (New Zealand) with a mean age of 3.6 months were selected for this study. The animals were divided into three groups as follows: Group I (GI), normal diet group, 8 rabbits; Group II (GII), hypercholesterolemic diet group, 13 rabbits; and Group III, candesartan-treated hypercholesterolemic group, 12 rabbits. During the 56-day study, the animals in GII and GIII were fed a specific diet, Nuvital® Lab (Nuvital, Colombo, Brazil) plus 1% cholesterol (Sigma-Aldrich®). The daily amount of food per animal was 600 grams 11. The diet, Nuvital® Lab (Nuvital, Colombo, Brazil), does not alter lipid metabolism in the animals. For the GIII group, 2.62 mg/kg/day of candesartan cilexetil (AstraZeneca, London, United Kingdom) was administered by oral gavage from day 1 through day 56. On day 56, the animals from GII and GIII were euthanized. Animals from GI were fed only Nuvital® Lab chow and were euthanized on day 28. Serum levels of total cholesterol, triglycerides and glucose were determined in fasting rabbits at the beginning of the experiment and the time of euthanasia. Euthanasia was performed by intravenous anesthesia with 5 ml pentobarbital, and the rabbit eyes were immediately placed in 4% paraformaldehyde (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) in 0.1 M phosphate, pH 7.4, for 4 hours. The eyes were then used for the morphometrical and immunohistochemical analyses of the choroid-sclera complex.

Tissue preparation

After fixation, the samples were evaluated macroscopically. A coronal section was performed at the level of the optic nerve, and the ocular globe was divided into two equal halves. The lower half was stored for future study, and the upper half was dehydrated, diaphanized and embedded in paraffin using a Leica® TP 1020 – Automatic Tissue Processor (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany). A Leica® EG1160 paraffin-embedding device was used to produce the paraffin blocks. A Leica® RM2145 Microtome was used to obtain 5-µm-thick sections for histology. The sections were placed on glass slides smeared with albumin, stained with hematoxylin-eosin and mounted with 24 × 900-mm coverslips using Entellan Mounting Media (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany).

Scleral and choroid histomorphometry

For quantitative analysis, the evaluated sections were stained with hematoxylin-eosin. With the aid of a 4x objective lens and a blue overhead projector marker, the hemi-sectioned ocular globe was divided manually into 10 equal segments from the pars plana to the contralateral pars plana. Segment images were obtained (10 images of each eye) using an Olympus BX50 microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) connected to a Sony BX50 camera (Sony Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). In each captured image, four linear morphometric measurements were taken using the Image Proplus® software supplied with the BX50 (Media Cybernetics Inc., Silver Spring, MD). Accordingly, 40 measurements were taken from each eye to evaluate choroidal and scleral thicknesses. Finally, the mean of the four measurements of each of the 10 segments was obtained. The results are expressed in micrometers.

Tissue preparation and immunohistochemical analysis

The histological slices were first blocked against endogenous peroxidase. They were then washed in deionized water and incubated in a moist chamber at 95°C for 20 minutes for antigen retrieval, after which the endogenous peroxidase was blocked again. Primary mouse anti-ICAM-1 monoclonal antibody (1∶100, Novocastra, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK) was then added to the slides. Next, the slices were incubated with a secondary antibody, Envision® System labeled polymer-HRP anti-mouse (DakoCytomation, Carpinteria, CA, USA), at room temperature for 30 min. The slices were then stained by incubation with freshly prepared DAB substrate (DakoCytomation, Carpinteria, CA, USA) for 3 to 5 minutes. Finally, the slides were counterstained with Mayer hematoxylin and mounted.

Positive and negative controls were used in all evaluations, and a masked observer initially analyzed the slides. In this analysis, positive and negative results for the marker detected by anti-ICAM-1 were recorded. The positive areas, which were a brownish color, were studied utilizing color morphometry. This procedure was performed by capturing images of three consecutive fields that were close to the optic nerve head with a BX50 Olympus microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) coupled to a Sony camera (Sony Corporation, Tokyo, Japan), Model DXC-107A, using a 40x objective. The computer program, Image Pro Plus, enabled the observer to select and color the positive areas and automatically determined the immunoreactive area in square micrometers. The data obtained were compiled in a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet (Redmond, WA) for statistical analysis. The immunoreactive area represents the sum of all positive areas in each of the three fields studied. This color morphometry method was previously used in other studies 12.

Statistical analysis

To compare the defined groups for treatment in relation to the quantitative variables, one-way analysis of variances (ANOVA) was performed. Multiple comparisons were made using the LSD (least significant difference) test. The baseline and euthanasia time evaluations within each group were analyzed using Student's t-test for paired samples. Normality was assessed with the Shapiro-Wilk test. Logarithmic transformation was performed for variables showing skewed data. Values of p<0.05 indicated statistical significance. Statistica 8.0 (StatSoft. Inc. 2300 East 14th Street Tulsa, Oklahoma, USA) was used for data processing.

Ethics

Animals were handled in compliance with the principles established by the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology (ARVO), and the protocol was approved by the Animal Research Committee of the Pontificia Catolica Universidade do Parana.

RESULTS

Lab variables

At baseline, there were no significant differences in the laboratory variables of the animals, both within the same group and between groups. Additionally, the rabbits did not show significant alterations in their glycemic values at the time of euthanasia. Conversely, at the time of euthanasia, total cholesterol, which was approximately 42 mg/dl at baseline, reached 2200.00 mg/dl in GII and 923.6 mg/dl in GIII. These increases were significant compared to GI. Triglyceride was approximately 53 mg/dl at baseline; at the end of the experiment, it increased to 168 mg/dl in GII and 171 mg/dl in GIII, which was a significant increase compared to GI.

Sclera and choroid analysis with hematoxylin-eosin

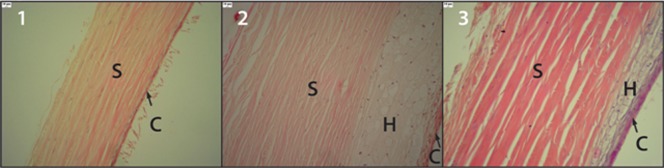

The sclera and choroids obtained from animals in GI had very few histiocytes (Figure 1.1). Conversely, a large number of histiocytes were observed in the sclera-choroidal complex from GII animals (Figure, 1.2). The sclera-choroidal complexes from GIII animals (Figure 1.3) had fewer histiocytes than GII, but more than GI.

Figure 1.

C- Choroid; S- Sclera; H- Histiocytes. Figure 1 shows the sclera and choroid from the GI group. They were of normal thickness, with very few histiocytes. Figure 2 shows the sclera and choroid from the GII group. They were of increased thickness, which was mainly due to the high number of histiocytes. Figure 3 shows the sclera and choroid from the GIII group. There were fewer histiocytes in GIII than in GII, and the thickness of the sclera and choroid were higher than in GI and lower than in GII.

Sclera and choroid morphometric analysis

A significant increase in the thickness of the sclera and choroid was observed in GII compared to GI and GIII (p<0.001). The thickness in GIII was significantly higher compared to GI (p = 0.008).

The differences in thickness of the sclera-choroidal complexes among the groups are shown in Figure 1. Table 1 shows the thicknesses of the sclera and choroid of the three groups in micrometers.

Table 1.

- Sclera and choroid thicknesses in micrometers.

| Variable | Group | n | Mean | Median | Min | Max | Standard Deviation | p-value* |

| Choroid and Sclera Morphometry | GI | 8 | 232.9 | 221.4 | 192.9 | 307.7 | 35.8 | |

| GII | 13 | 382.5 | 387.9 | 254.0 | 475.0 | 60.5 | ||

| GIII | 12 | 284.8 | 278.5 | 240.0 | 390.5 | 43.4 | <0.001 |

*ANOVA, p<0.05.

GI vs. GII: p<0.001; GI vs. GIII: p = 0.008; GII vs. GIII: p<0.001.

GI - Normal diet group; GII - Cholesterol-enriched diet group; GIII - Cholesterol-enriched diet plus candesartan diet group.

Immunoreactivity to ICAM-1

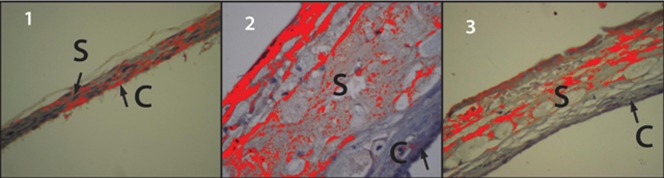

The hypercholesterolemic group (GII) exhibited a significant increase in immunoreactivity to ICAM-1 compared to GI and GIII (p<0.001). Immunoreactivity was also significantly increased in GIII in relation to GI (p = 0.041). Table 2 shows the values of the areas immunoreactive to ICAM-1 antibody in square micrometers, as determined by the color morphometry technique.

Table 2.

- Area showing immunoreactivity to ICAM-1 antibody, in square micrometers, obtained from the color morphometry analysis.

| Variable | Group | n | Mean | Median | Min | Max | Standard Deviation | p-value* |

| Area immunoreactive to ICAM-1 | GI | 8 | 607.0 | 218.5 | 50.2 | 2200.4 | 858.7 | |

| GII | 13 | 3600.2 | 3288.7 | 1867.7 | 6368.8 | 1377.3 | ||

| GIII | 12 | 1231.3 | 1267.6 | 119.9 | 3048.4 | 951.3 | <0.001 |

*Nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test, p<0.05.

GI vs. GII: p<0.001; GI vs. GIII: p = 0.041; GII vs. GIII: p<0.001.

GI - Normal diet group; GII - Cholesterol-enriched diet group; GIII - Cholesterol-enriched diet plus candesartan diet group.

In GI animals, the choroid-sclera complex was predominantly stained blue, revealing a low level of ICAM-1 immunoreactivity (Figure 2.1). Conversely, in GII animals, the choroid-sclera complex was predominantly orange, revealing a high level of immunoreactivity (Figure 2.2). Figure 2.3, which represents the GIII choroid-sclera complex, shows that the ICAM-1 immunoreactivity level in GIII was higher than in GI (Figure 2.1) and lower than in GII (Figure 2.2).

Figure 2.

C- Choroid; S- Sclera. 1) GI sclera and choroid. The prevalence of the bluish color demonstrates the low levels of immunoreactivity to ICAM-1. 2) GII sclera and choroid. The prevalence of the orange color demonstrates the high levels of immunoreactivity to ICAM-1. 3) GIII sclera and choroid. The orange areas indicate immunoreactivity to ICAM-1. Specifically, this reactivity was higher than in GI and lower than in GII.

DISCUSSION

In this study, rabbits were fed a cholesterol-enriched diet, and the effects of candesartan on ICAM-1 expression and macrophage accumulation in the sclera and choroid were assessed. As has been demonstrated in the cardiovascular system 3,13, dyslipidemia caused significant increases in ICAM-1 expression in the sclera and choroid in GII and GIII animals (Table 2). The role of immunoglobulins in the formation of atheromatous plaques in the great vessels is well defined. ICAM-1 induces the adhesion of the circulating monocytes to the vascular endothelium. Once in the arterial wall intima, these cells are transformed into macrophages, which contribute to the formation of atherosclerotic plaque 3,13. In the normal eye, ICAM-1 immunoglobulin is expressed at low levels in the choroid and retina vascular endothelium, retinal pigment epithelium (EPR), Bruch's membrane and external limiting membrane 14-16. However, in pathological conditions, such as in exudative ARMD, a significant increase in ICAM-1 expression has been observed in the EPR cells and choroidal vessels 9,. Due to the role of ICAM-1 in regulating leucocyte adherence 5, the increased expression of this immunoglobulin may account for the increase in macrophages and, consequently, the increased thickness of the sclera-choroid complex (Table 1), which was observed here and previously in other studies 12,19.

In this study, by inducing hypercholesterolemia, we attempted to create a physiopathogenic condition that is similar to ARMD, in which the accumulation of oxidized lipids attracts macrophages, which can clear the oxidized lipids 4,20. Besides producing vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), macrophages are also sources of pro-inflammatory and pro-angiogenic cytokines, such as interleukin (IL)-6 and tumor necrosis factor (TNF), which mediate inflammatory responses and contribute to the formation of the sub-retinal neovascular membrane ,21-25. It is important to note that oxidized low-density lipoprotein (LDL) is a powerful stimulus that increases the expression of chemotactic and adhesion molecules, which then attracts macrophages to the inflammatory tissue. This process occurs in both atherosclerosis and ARMD 4,20. It is also known that not only the oxidized but also the native LDL induces the increase in the ICAM-1 expression 26. Hence, LDL, which is deposited on the Bruch's membrane, formed by the degradation of photoreceptor outer segments 20,27, can increase the expression of these adhesion molecules, a determinant aspect in the increase of macrophages and development of AMRD.

As AMRD and atherosclerosis present similar physiopathogenic mechanisms 1,2,3,13, it is expected that the drugs used to treat these diseases will have equivalent characteristics and performances. Candesartan blocks the angiotensin II AT-1 receptor, thereby preventing angiotensin-mediated effects. It is important to note that angiotensin II induces the increased expression of cytokines (IL-6, IL-1, TNF-α), chemokines (monocyte chemotactic protein-1 – MCP-1) and leucocyte adhesion molecules (selectins P, E and L; integrins a1 and b2; VCAM; ICAM) 28,29. Moreover, among all of the renin-angiotensin system (RAS) blockers, candesartan is considered to have the strongest affinity to the AT-1 receptor. This class of drug is widely used to treat arterial hypertension and has been shown to reduce the levels of soluble ICAM-1 in hypercholesterolemic patients 30. Experiments have demonstrated that the blockade of AT-1 receptors of the RAS reduces the numbers of macrophages, monocytes and T lymphocytes in atheromatous plaques 7. In the present study, the use of candesartan to block the angiotensin II AT-1 receptor (GIII) significantly reduced the expression of ICAM-1 in the sclera and choroid compared to GII (p<0.001) (Table 2), which may have reduced the thickness of the GIII sclera-choroid complex in relation to GII (p<0.001) (Table 1).

In a recent study, our group showed that olmesartan reduced the expression of MCP-1 and the accumulation of macrophages in the sclera and choroid of hypercholesterolemic rabbits 31. Besides blocking the binding of angiotensin II to the AT1 receptors, olmesartan exerts a mild modulatory activity on PPAR-gamma receptors 32. Thus, the olmesartan-mediated decrease of macrophages in the sclera-choroid complex could also be accounted for by the drug's agonistic effect on the PPAR-gamma receptors 12. In the present study, the RAS blockade was induced by candesartan, which does not exert this agonistic effect on PPAR-gamma receptors. This finding shows that RAS blockade alone can decrease the accumulation of macrophages in the sclera-choroid complex, as occurs in the great vessels 33.

It has been demonstrated that the blockade of the angiotensin II AT-1 receptor reduces the presence of macrophages and the expression of inflammatory markers in the RPE and choroid, thus significantly affecting the formation of the sub-retinal neovascular membrane 9,10,34. Hence, by playing an important role in the pathological processes of angiogenesis and inflammation 35, the angiotensin II AT-1 receptor may represent a new target for the treatment of ARMD.

In this study, we used immunohistochemistry to analyze the sclera and choroid of hypercholesterolemic rabbits. Immunohistochemistry, when used on paraffin-embedded material, enables the researcher to locate and identify proteins in the analyzed tissues. The authors acknowledge that while the Western blot technique offers high sensitivity for detection and would improve the analysis of the studied protein, it usually requires fresh or frozen tissues. As the ocular globes were fixed in paraformaldehyde and then embedded in paraffin, it was not possible to complement the study with the Western blot technique.

ACKNOWLEGMENTS

The authors are particularly grateful for the time and assistance provided by the staff of the Graduate Department of the Pontificia Universidade Católica do Paraná and the Angelina Caron Hospital with regards to the use of their labs and equipment for the experiment.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest was reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Friedman E. A hemodynamic model of the pathogenesis of age-related macular degeneration. Am J Ophthalmol. 1997;124(5):677–82. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)70906-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Friedman E. The role of the atherosclerotic process in the pathogenesis of age-related macular degeneration. 2000;130(5):658–63. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(00)00643-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ross R. Atherosclerosis: an inflammatory disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(2):115–26. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199901143400207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Killingsworth MC, Sarks JP, Sarks SH. Macrophages related to Bruch's membrane in age-related macular degeneration. Eye (Lond) 1990;4(Pt 4):613–21. doi: 10.1038/eye.1990.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van de Stolpe A, van der Saag PT. Intercellular adhesion molecule-1. J Mol Med. 1996;74(1):13–33. doi: 10.1007/BF00202069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mullins RF, Skeie JM, Malone EA, Kuehn MH. Macular and peripheral distribution of ICAM-1 in the human choriocapillaris and retina. Mol Vis. 2006;12:224–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van der Hoorn JW, Kleemann R, Havekes LM, Kooistra T, Princen HM, Jukema JW. Olmesartan and pravastatin additively reduce development of atherosclerosis in APOE*3Leiden transgenic mice. J Hypertens. 2007;25(12):2454–62. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3282ef79f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sakurai E, Anand A, Ambati BK, van Rooijen N, Ambati J. Macrophage depletion inhibits experimental choroidal neovascularization. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44(8):3578–85. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nagai N, Oike Y, Izumi-Nagai K, Urano T, Kubota Y, Noda K, et al. Angiotensin II type 1 receptor-mediated inflammation is required for choroidal neovascularization. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26(10):2252–9. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000240050.15321.fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Satofuka S, Ichihara A, Nagai N, Noda K, Ozawa Y, Fukamizu A, et al. (Pro)renin Receptor Promotes Choroidal Neovascularization by Activating Its Signal Transduction and Tissue Renin-Angiotensin System. Am J Pathol. 2008;173(6):1911–8. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.080457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sun YP, Lu NC, Parmley YWW, Hollenbeck CB. Effects of cholesterol diets on vascular function and atherogenesis in rabbits. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 2000;224(3):166–71. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1373.2000.22416.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Torres RJ, Muccioli C, Maia M, Noronha L, Luchini A, Alessi A, et al. Sclerochorioretinal abnormalities in hypercholesterolemic rabbits treated with rosiglitazone. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging. 2010;41(5):562–71. doi: 10.3928/15428877-20100726-05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Libby P. Inflammation in atherosclerosis. Nature. 2002;420(6917):868–74. doi: 10.1038/nature01323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duguid IG, Boyd AW, Mandel TE. Adhesion molecules are expressed in the human retina and choroid. Curr Eye Res. 1992;11(Suppl):153–9. doi: 10.3109/02713689208999526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elner SG, Elner VM, Pavilack MA, Todd RF, Mayo-Bond L, Franklin WA, et al. Modulation and function of intracellular adhesion molecule-1 (CD54) on human retinal epithelial cells. Lab Invest. 1992;66(2):200–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McLeod S, Lefer DJ, Merges C, Lutty GA. Enhanced Expression of Intracellular Adhesion Molecule-1 and P-Selectin in the Diabetic Human Retina and Choroid. Am J Pathol. 1995;147(3):642–53. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shen WY, Yu MJ, Barry CJ, Constable IJ, Rakoczy PE. Expression of cell adhesion molecules and vascular endothelial growth factor in experimental choroidal neovascularisation in the rat. Br J Ophthalmol. 1998;82(9):1063–71. doi: 10.1136/bjo.82.9.1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sakurai E, Taguchi H, Anand A, Ambati BK, Gragoudas ES, Miller JW, et al. Targeted disruption of the CD18 or ICAM-1 gene inhibits choroidal neovascularization. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44(6):2743–9. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Torres RJA, Maia M, Noronha L, Farah ME, Luchini A, Brik D, et al. Avaliacao das Alteracoes Precoces na Coroide e Esclera Ocorridas em Coelhos Hipercolesterolemicos. Estudo histologico e histomorfometrico. Arq Bras Oftalmol. 2009;72(1):68–74. doi: 10.1590/s0004-27492009000100014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ruberti JW, Curcio CA, Millican CL, Menco BP, Huang JD, Johnson M. Quick-freeze/deep-etch visualization of age-related lipid accumulation in Bruch's membrane. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44(4):1753–9. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-0496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grossniklaus HE, Ling J X, Wallace T M, Dithmar S, Lawson DH, Cohen C, et al. Macrophage and retinal pigment epithelium expression of angiogenic cytokines in choroidal neovascularization. Mol Vis. 2002;8:119–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tsutsumi C, Sonoda KH, Egashira K, Qiao H, Hisatomi T, Nakao S, et al. The critical role of ocular-infiltrating macrophages in the development of choroidal neovascularization. J Leukoc Biol. 2003;74(1):25–32. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0902436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Markomichelakis NN, Theodossiadis PG, Sfikakis PP. Regression of neovascular age-related macular degeneration following infliximab therapy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;139(3):537–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2004.09.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shi X, Semkova I, Muther PS, Dell S, Kociok N, Joussen AM. Inhibition of TNF-alpha reduces laser-induced choroidal neovascularization. Exp Eye Res. 2006;83(6):1325–34. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2006.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cohen T, Nahari D, Cerem LW, Gera N, Levi B. Interleukin-6 induces the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(2):736–41. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.2.736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smalley DM, Lin JH, Curtis ML, Kobari Y, Stemerman MB, Pritchard KA., Jr Native LDL increases endothelial cell adhesiveness by inducing intercellular adhesion molecule-1. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1996;16(4):585–90. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.16.4.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pauleikhoff D, Harper CA, Marshall J, Bird AC. Aging changes in Bruch's membrane: a histochemical and morphologic study. Ophthalmology. 1990;97(2):171–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marchesi C, Paradis P, Schiffrin EL. Role of the renin-angiotensin system in vascular inflammation. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2008;29(7):367–74. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Montecucco F, Pende A, Mach F. The renin-angiotensin system modulates inflammatory processes in atherosclerosis: evidence from basic research and clinical studies. Mediators Inflamm. 2009;2009:752406. doi: 10.1155/2009/752406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wassmann S, Hilgers S, Laufs U, Bohm M, Nickenig G. Angiotensin II type 1 receptor antagonism improves hypercholesterolemia-associated endothelial dysfunction. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2002;22(7):1208–12. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.0000022847.38083.b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Torres RJA, Noronha L, Casella AMB, Grobe SF, Martins IC, Torres RRA, et al. Effect of Olmesartan on Leukocyte Recruitment in Choroid-Sclera Complex in Hypercholesterolemia Model. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2013;29(8):709–14. doi: 10.1089/jop.2012.0142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marshall TG, Lee RE, Marshall FE. Common angiotensin receptor blockers may directly modulate the immune system via VDR, PPAR and CCR2b. Theor Biol Med Model. 2006;3:1. doi: 10.1186/1742-4682-3-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhou XF, Yin HC, Zhu WL, Shen L, Yu T, Li SA, et al. Prevention of rupture of atherosclerotic plaque by Candesartan in rabbit model. Zhonghua Bing Li Xue Za Zhi. 2010;39(2):106–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hikichi T, Mori F, Takamiya A, Sasaki M, Horikawa Y, Takeda M, et al. Inhibitory effect of losartan on laser-induced choroidal neovascularization in rats. Am J Ophthalmol. 2001;132(4):587–9. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(01)01139-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brasier AR, Recinos A, Eledrisi MS. Vascular inflammation and the renin-angiotensin system. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2002;22(8):1257–66. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.0000021412.56621.a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]