Abstract

Background

In the Carotid Revascularization Endarterectomy versus Stenting Trial (CREST), the composite primary endpoint of stroke, myocardial infarction, or death during the periprocedural period or ipsilateral stroke thereafter did not differ between carotid artery stenting and carotid endarterectomy for symptomatic or asymptomatic carotid stenosis. A secondary aim of this randomised trial was to compare the composite endpoint of restenosis or occlusion.

Methods

Patients with stenosis of the carotid artery who were asymptomatic or had had a transient ischaemic attack, amaurosis fugax, or a minor stroke were eligible for CREST and were enrolled at 117 clinical centres in the USA and Canada between Dec 21, 2000, and July 18, 2008. In this secondary analysis, the main endpoint was a composite of restenosis or occlusion at 2 years. Restenosis and occlusion were assessed by duplex ultrasonography at 1, 6, 12, 24, and 48 months and were defined as a reduction in diameter of the target artery of at least 70%, diagnosed by a peak systolic velocity of at least 3·0 m/s. Studies were done in CREST-certified laboratories and interpreted at the Ultrasound Core Laboratory (University of Washington). The frequency of restenosis was calculated by Kaplan-Meier survival estimates and was compared during a 2-year follow-up period. We used proportional hazards models to assess the association between baseline characteristics and risk of restenosis. Analyses were per protocol. CREST is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, number NCT00004732.

Findings

2191 patients received their assigned treatment within 30 days of randomisation and had eligible ultrasonography (1086 who had carotid artery stenting, 1105 who had carotid endarterectomy). In 2 years, 58 patients who underwent carotid artery stenting (Kaplan-Meier rate 6·0%) and 62 who had carotid endarterectomy (6·3%) had restenosis or occlusion (hazard ratio [HR] 0·90, 95% CI 0·63–1·29; p=0·58). Female sex (1·79, 1·25–2·56), diabetes (2·31, 1·61–3·31), and dyslipidaemia (2·07, 1·01–4·26) were independent predictors of restenosis or occlusion after the two procedures. Smoking predicted an increased rate of restenosis after carotid endarterectomy (2·26, 1·34–3·77) but not after carotid artery stenting (0·77, 0·41–1·42).

Interpretation

Restenosis and occlusion were infrequent and rates were similar up to 2 years after carotid endarterectomy and carotid artery stenting. Subsets of patients could benefit from early and frequent monitoring after revascularisation.

Funding

National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke and Abbott Vascular Solutions

INTRODUCTION

In the Carotid Revascularization Endarterectomy versus Stenting Trial (CREST), no difference was found between carotid artery stenting (CAS) and carotid endarterectomy (CEA) for the primary endpoint of stroke, myocardial infarction (MI), or death during the periprocedural period and ipsilateral stroke thereafter.1 The secondary analysis of the individual components of the primary endpoint established that stroke occurred more frequently after carotid artery stenting, as did myocardial infarction after carotid endarterectomy.1 That the frequency of the composite endpoint did not differ between carotid artery stenting and carotid endarterectomy underscores the need for a comparison of the anatomic durability of these revascularisation procedures. Many participants in CREST were asymptomatic, so the long-term durability of revascularisation becomes even more important.

Restenosis after CAS2–5 and CEA6–8 has been reported to range from 5% to 20%, depending upon the definition of restenosis and duration of follow-up. We report the two-year anatomic durability of CAS and CEA (restenosis defined as ≥70% diameter-reducing stenosis or target artery occlusion occurring beyond 30 days of the procedure), a pre-specified secondary endpoint of CREST. We also identify factors affecting risk of restenosis and compare frequency of stroke and repeat revascularisation between the treatment groups.

METHODS

Study design and patients

The study design and the primary results of CREST have been reported previously.1,9,10 Briefly, patients were enrolled at 117 clinical centres in the USA and Canada between Dec 21, 2000, and July 18, 2008. Patients who had had a transient ischaemic attack, amaurosis fugax, or a minor non-disabling stroke involving the study carotid artery within 180 days before randomisation were eligible if they had stenosis of 50% or more by angiography, 70% or more by ultrasonography, or 70% or more by computed tomography angiography or magnetic resonance angiography when the stenosis by ultrasonography was 50–69%. Patients who were asymptomatic were eligible when they had stenosis of 60% or more by angiography, 70% or more by ultrasonography, or 80% or more by computed tomography angiography or magnetic resonance angiography when the stenosis on ultrasonography was 50–69%. The full eligibility criteria have been reported elsewhere.1,9,10

The protocol was approved by the ethics committees of all study institutions and administrative sites. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before their revascularisation procedure.

Randomisation and masking

Patients were randomly assigned to either carotid artery stenting or carotid endarterectomy through a web-based system with a permuted block design (random block sizes of two, four, or six), and were stratified according to centre and symptomatic status. Randomisation occurred after the patient and treating physician could arrange for revascularisation to be done within 2 weeks. Stroke and myocardial infarction were adjudicated by specialty committees masked to treatment assignment. All other outcomes were assessed by investigators unmasked to treatment allocation. Investigators and patients were unmasked.

Procedures

CEA was performed according to well-established techniques (standard or eversion endarterectomy) based on the individual preferences of 477 participating surgeons. CAS was performed with a pre-specified self-expanding nitinol stent and an embolic protection device (RX Acculink and RX Accunet, Abbott Vascular, Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA). The 224 participating interventionists were selected after successful completion of a mandatory non-randomized lead-in credentialing phase of CAS procedures.10,11

In order to maintain consistency in the follow-up time points, patients that underwent their assigned revascularization procedure within 30 days of randomization and who had at least one follow-up ultrasound within the 24-month period were included in this analysis. In addition, we focus on patients receiving their assigned therapy because of interest in the restenosis rates specifically associated with CAS and CEA (and not the intention to be treated by these procedures), and because those not receiving any therapy did not establish a condition of lack of stenosis to allow them to be eligible for restenosis.

Duplex ultrasonography was done at baseline and 1, 6, 12, 24, and 48 months after revascularisation. Duplex ultrasonography12 was undertaken at CREST-certified12 clinical centre vascular laboratories with a standardized protocol that stipulated 16 doppler waveform samples at every examination (eight samples were taken from each side of the neck: six at 1–2 cm intervals along the common and internal carotid arteries, one from the external carotid artery, and one from the vertebral artery). Waveform samples were to be obtained at a 60 degree angle between the ultrasound beam and the long axis of the vessel. The highest systolic velocity measurement from each treated carotid pathway was used to identify restenosis.

Ultrasound laboratories differ in the methods used, and velocity measurements are angle-dependent.13 Accordingly, ultrasound images and Doppler waveforms were forwarded to the Ultrasound Core Laboratory, at the University of Washington Ultrasound Reading Center (URC) for uniform evaluation and coding. The clinical centers submitted ultrasound data primarily in digital form. A small minority of centers submitted paper prints that were scanned and digitized at the URC. The velocity values submitted from the clinical centers were entered into the URC database.

Images and waveforms were read by a registered sonographer certified by the American Registry of Diagnostic Medical Sonographers and trained by the URC. Images and waveforms were read by a registered sonographer certified by the American Registry of Diagnostic Medical Sonographers and trained by the URC. The reader confirmed images, values, and alignment of the ultrasound-beam cursor with the vessel axis on the B-mode image; image and waveform readings were then reviewed by a senior sonographer or the URC Director (KWB). Both reader and reviewer verified the selection, location, labelling of every image and waveform pair, and cursor alignment. When the cursor was misaligned, the doppler examination angle was measured again and the angle-adjusted velocity was recalculated. The equation for re-calculation was (new velocity) = (old velocity)*cos(old angle)/cos(new angle).

Corrections and changes marked in the reader/reviewer process were entered into the database and used to update the information. If the reviewer disagreed with the reader, the case was returned to the reader for confirmation. If the disagreement was not resolved, the case went to an adjudicator who rendered a final decision, and who presented the case to the readers and reviewers to minimize future interpretation differences. The final adjudicated angle-adjusted velocity value and verified DUS examination was reported by the URC and these values were used in the current analysis.

The main endpoint in this secondary analysis was a composite of restenosis, defined as 70% or more diameter-reducing stenosis, or target-artery occlusion occurring at the ultrasound scans at 1, 6, 12, or 24 months. The 70% threshold to define high-grade restenosis is the most accepted threshold and has been used in the Carotid and Vertebral Artery Transluminal Angioplasty Study (CAVATAS),3 the Stent-Protected Angioplasty versus Carotid Endarterectomy (SPACE) trial,4 and the Endarterectomy versus Angioplasty in Patients with Severe Symptomatic Carotid Stenosis (EVA-3S) trial.5 Assessment of restenosis was done when the peak systolic velocity at any location within the treated internal or common carotid artery reached or exceeded 3·0 m/s. Analysis of the frequency of high-grade restenosis and occlusion was a prespecified secondary analysis of the CREST protocol. The decision to use 3·0 m/s as the definition for restenosis was also made before unblinding of the restenosis data. Several single-institution reports 14-18 support the use of 3·0 m/s or more as an appropriate threshold to identify high-grade restenosis.

A determination of target artery occlusion was made on DUS when no flow-signal was detected in any location within the treated internal or common carotid artery. Included in this category were arteries with near occlusion defined as having a zero diastolic velocity, low systolic velocity in some locations, or an inability to find Doppler signals at some locations within the treated arterial segments. Residual stenosis immediately after revascularization was only measured in the CAS group and was therefore not compared with CEA. The frequency with which ipsilateral stroke occurred in the post periprocedural period and the frequency of repeat surgical revascularization, balloon angioplasty, or repeat CAS performed on target arteries were also evaluated.

Concerns have been raised that ultrasound velocity criteria designed for native carotid arteries could over-estimate stenosis in the presence of a stent,14,19 because the reduced compliance of the vessel wall could increase the peak systolic velocity.19 Therefore, use of an appropriate velocity threshold is central to the comparison of restenosis after carotid endarterectomy and carotid artery stenting. We have used the threshold of 3·0 m/s to investigate the primary endpoint, acknowledging that it is not universally accepted. To address potential threshold-dependent variations in restenosis determination, we undertook an exploratory analysis in which different thresholds (greater or less than 3·0 m/s) were applied to the data. Restenosis rates thus obtained for carotid artery stenting and carotid endarterectomy were compared.

Statistical analysis

The frequency of restenosis was calculated by Kaplan-Meier survival estimates and was compared during a 2-year follow-up period between patients undergoing carotid artery stenting and carotid endarterectomy. In analyses specified after the initial analysis plan but before the data were reviewed, we used proportional hazards analyses to assess the univariate association between baseline clinical characteristics and the risk of the composite endpoint in the combined cohort and for carotid artery stenting and carotid endarterectomy separately to identify potential differences in risk factors as defined at the time of randomisation. Backwards stepwise procedures were used to establish the most parsimonious model for the combined cohort. We tested the clinical characteristics diabetes, dyslipidaemia, hypertension, smoking, previous cardiovascular disease or coronary artery bypass grafting, pretreatment stenosis category, age, symptomatic status, ethnic origin, sex, time to treatment after randomisation, and antiplatelet treatment. The number of strokes that occurred in the 2 years after the procedures was compared by treatment group in the patients with and without the composite endpoint. Additionally, we compared the proportion of patients undergoing repeat revascularisation. Analyses were done with SAS (version 9.2).

Role of the funding sources

Representatives of the study sponsors were involved in the review of the manuscript and the study design, but were not directly involved in the collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data, the writing of the report, or in the decision to submit the paper for publication. The corresponding author had full access to the data for this study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

RESULTS

Of the 1262 patients randomly assigned to carotid artery stenting who had data included in the main CREST analysis, 1136 received their allocated treatment and 1123 did so within 30 days of randomisation. Of the 1240 patients randomly assigned to carotid endarterectomy who had data included in the main CREST analysis, 1184 received their assigned treatment and 1151 did so within 30 days of randomisation. Reasons for patients not receiving their assigned treatment have been reported previously.1 Within our cohort, 37 patients who underwent carotid artery stenting and 46 who underwent carotid endarterectomy did not have carotid duplex ultrasonography during follow-up data supplied to the Ultrasound Core Laboratory. Therefore, 2191 patients received their assigned treatment within 30 days of randomisation and had ultrasonography reviewed at the Ultrasound Core Laboratory, and form the analytic cohort for this report (1086 undergoing carotid artery stenting, 1105 undergoing carotid endarterectomy).

Table 1 shows baseline clinical characteristics. Patients excluded from this secondary analysis were older, less likely to be white or dyslipidaemic, and more likely to be female and have hypertension than were those who were included (table 1). Demographic characteristics, symptomatic status, and risk-factor distribution did not differ between those who had carotid artery stenting versus those having carotid endarterectomy (table 1). However, patients who underwent carotid endarterectomy had their procedures slightly later than did those receiving carotid artery stenting, and more patients undergoing carotid artery stenting received antiplatelet treatment than did those assigned to carotid endarterectomy (table 1). The duration of follow-up of patients undergoing carotid artery stenting versus carotid endarterectomy was similar in our cohort (mean 17·2 months [SD 7·9] vs 17·8 months [8·2]; median 24 months [IQR 12–24] in both groups). The proportion of cases in which reanalysis of the images or discussion about the results occurred was small: reanalysis was necessary in 3·1% of patients at baseline, 2·9% at 1 month, 2·2% at 6 months, 3·0% at 12 months, and 1·6% at 24 months.

Table 1.

Baseline clinical characteristics

| CREST restenosis analysis cohort (n=2191) | CREST patients excluded from analysis (n=311) | p value | Treatment groups | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carotid artery stenting group (n=1086) | Carotid endarterectomy group (n=1105) | p value | ||||

| Age (years) | 68·9 (8·8) | 70·4 (9·0) | 0.0041 | 68·6 (9·0) | 69·1 (8·7) | 0.2580 |

| Women | 742/2191 (34%) | 130/311 (42%) | 0.0060 | 382/1086 (35%) | 360/1105 (33%) | 0.1993 |

| White | 2057/2191 (94%) | 275/311 (88%) | 0.0003 | 1017/1086 (94%) | 1040/1105 (94%) | 0.6453 |

| Symptomatic | 1159/2191 (53%) | 162/311 (52%) | 0.7893 | 571/1086 (53%) | 588/1105 (53%) | 0.7661 |

| Hypertension* | 1868/2189 (85%) | 273/303 (90%) | 0.0255 | 919/1085 (85%) | 949/1104 (86%) | 0.4048 |

| Diabetes† | 667/2186 (31%) | 92/303 (30%) | 0.9578 | 325/1083 (30%) | 342/1103 (31%) | 0.6127 |

| Dyslipidaemia‡ | 1862/2181 (85%) | 231/300 (77%) | 0.0002 | 914/1081 (85%) | 948/1100 (86%) | 0.2813 |

| Present smoker | 573/2159 (27%) | 73/301 (24%) | 0.3982 | 291/1070 (27%) | 282/1089 (26%) | 0.4937 |

| Previous cardiovascular disease or coronary artery bypass graft | 965/2121 (46%) | 119/290 (41%) | 0.1519 | 471/1054 (45%) | 494/1067 (46%) | 0.4563 |

| Pre-treatment stenosis percent ≥ 70% | 1884/2191 (85%) | 267/310 (86%) | 0.9466 | 938/1086 (86%) | 946/1105 (86%) | 0.6078 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 141·4 (20·0); n=2177 | 142·0 (22·6); n=292 | 0.6402 | 141·4 (19·6); n=1078 | 141·3 (20·5); n=1099 | 0.8739 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 74·1 (11·5); n=2178 | 73·2 (11·5); n=291 | 0.2420 | 74·0 (11·6); n=1079 | 74·2 (11·4); n=1099 | 0.6815 |

| Time from randomization to treatment (days) | 7 (3–11) | --- | --- | 6 (2–10) | 7 (3–12) | 0.0184 |

| Treatment within 7 days of randomization | 1249/2191 (57%) | --- | --- | 645/1086 (59%) | 604/1105 (55%) | 0.0253 |

| Lipid lowering treatment § | 1664/1808 (92%) | 197/220 (90%) | 0.2046 | 824/889 (93%) | 840/919 (91%) | 0.3131 |

| Anti-platelet treatment ¶ | 2038/2163 (94%) | --- | --- | 1022/1059 (97%) | 1016/1104 (92%) | <0.0001 |

| Anti-hypertensive treatment | 1734/1805 (96%) | 250/260 (96%) | 0.9459 | 845/888 (95%) | 889/917 (97%) | 0.0506 |

Data are mean (SD), n/N (%), or median (IQR). Sample sizes vary for specific characteristics because data are missing for a small number of patients. CREST=Carotid Revascularization Endarterectomy versus Stenting Trial.

Hypertension was defined as a blood pressure of 140/80 mm Hg or more.

Diabetes was defined by a fasting serum glucose concentration of 5 mmol/L or more or HbA1C of 42 mmol/L or more.

Dyslipidaemia was defined by concentrations of low-density lipoproteins of 2.5 mmol/L or more.

Use of cholesterol medication was recorded only in those who answered affirmatively to dyslipidaemia.

Additional details obtained since 2010 about antiplatelet treatment have been incorporated into this variable (addition of patients who received an appropriate loading dose of clopidogrel before carotid artery stenting), resulting in non-significant changes from percentages reported previously.1

The composite outcome of restenosis or occlusion occurred in 120 patients (58 carotid artery stenting, 62 carotid endarterectomy). The Kaplan-Meier estimate for the frequency of the composite outcome in 2 years was 6·0% for carotid artery stenting and 6·3% for carotid endarterectomy (hazard ratio [HR] 0·90, 95% CI 0·63–1·29; p=0·58, adjusted for age, sex, and symptomatic status). 113 patients developed restenosis alone (56 carotid artery stenting, 57 carotid endarterectomy). In both groups, the Kaplan-Meier estimate of the 2-year frequency of restenosis was 5·8%. In the same period, eight patients developed an occlusion of the treated carotid artery, of which three (<1%) had had carotid artery stenting and five (<1%) carotid endarterectomy. One patient who underwent carotid endarterectomy had restenosis that subsequently occluded. Because of the fairly wide intervals between assessments during which restenosis could occur, we fitted a sensitivity analysis with a parametric accelerated failure time model to account for interval censoring and with underlying exponential and Weibull distributions. Neither provided evidence of a treatment difference in restenosis rates (pexponential=0·35; pWeibull=0·34).

Although limited by the number of patients with duplex ultrasonography after 24 months (856 patients had an ultrasound at 36 months and 385 had one at 48 months), our data can be used to provide initial long-term estimated 48-month restenosis rates. The duration of follow-up of patients in this extended cohort was similar between groups (carotid artery stenting mean 24·5 months [SD 14·7] vs carotid endarterectomy 23·7 months [14·9]; median 24 months [IQR 12–36] in both groups). At 4 years, the composite outcome of restenosis or occlusion occurred in 122 patients (60 carotid artery stenting, 62 carotid endarterectomy). The Kaplan-Meier estimate for the frequency of the composite outcome in 4 years was 6·7% for carotid artery stenting and 6·2% for carotid endarterectomy (HR 0·94, 95% CI 0·66–1·33; p=0·71, adjusted for age, sex, and symptomatic status; figure 1).

Figure 1.

Four-year Kaplan-Meier graph demonstrating restenosis or occlusion in patients randomized to undergo carotid artery stenting versus carotid endarterectomy. There are more subjects included in this analysis and in the Figure than are listed in Table 1 (i.e. some subjects had only 36 or 48 month US but not 24 month US, and so could be included in this analysis which extends past 2 years). CAS=Carotid artery stenting, CEA=Carotid endarterectomy, n=number of patients assessed at each time point, day 0 is defined as the date for the CAS or CEA procedure.

Patients with the composite outcome were more likely to be younger, women, hypertensive, diabetic, and dyslipidaemic than were those who did not reach the outcome (table 2). Backwards stepwise analysis indicated female sex, diabetes, and dyslipidaemia were related to restenosis (table 2). Frequency of restenosis did not differ on the basis of symptomatic status (table 2). Frequency of restenosis in symptomatic versus asymptomatic patients was not significantly different in the carotid endarterectomy group (Kaplan-Meier estimate 6·0% [SE 1·1] vs 6·6% [1·1]; log rank p=0·42) or in those who underwent carotid artery stenting (4·9% [1·0] vs 7·2% [1·2]; log rank p=0·11).

Table 2.

Comparison of clinical characteristics of patients with or without restenosis

| No restenosis (n=2071) | Restenosis (n=120) | p value for group differences in composite endpoint | Univariate HR (95% CI) | Multivariable HR (95% CI)* | Most Parsimonious Model HR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carotid artery stenting | 1028/2071 (50%) | 58/120 (48%) | 0.781 | 0·94 (0·65–1·34) | 0·94 (0·65–1·37) | |

| Age (years) | 69·0 (8·8) | 67·1 (9·6) | 0.025 | 0·80 (0·66–0·98) | 0·92 (0·73–1·17) | |

| Women | 686/2071 (33%) | 56/120 (47%) | 0.0023 | 1·75 (1·23–2·51) | 1·83 (1·26–2·67) | 1·79 (1·25–2·56) |

| White | 1945/2071 (94%) | 112/120 (93%) | 0.7957 | 0·82 (0·40–1·68) | 0·89 (0·43–1·86) | |

| Symptomatic | 1105/2071 (53%) | 54/120 (45%) | 0.0746 | 0·74 (0·51–1·05) | 0·86 (0·58–1·28) | |

| Hypertension† | 1757/2069 (85%) | 111/120 (93%) | 0.0225 | 2·16 (1·09–4·25) | 1·57 (0·78–3·14) | |

| Diabetes‡ | 607/2066 (29%) | 60/120 (50%) | <.0001 | 2·39 (1·67–3·42) | 2·22 (1·52–3·26) | 2·31 (1·61–3·31) |

| Dyslipidemia§ | 1751/2062 (85%) | 111/119 (93%) | 0.0121 | 2·34 (1·14–4·80) | 1·97 (0·90–4·31) | 2·07 (1·01–4·26) |

| Present smoker | 534/2041 (26%) | 39/118 (33%) | 0.0995 | 1·38 (0·94–2·03) | 1·47 (0·95–2·27) | |

| Previous cardiovascular disease or coronary artery bypass graft | 909/2007 (45%) | 56/114 (49%) | 0.4242 | 1·18 (0·82–1·71) | 1·07 (0·73–1·57) | |

| Pre-treatment stenosis percent ≥70% | 1779/2071 (86%) | 105/120 (88%) | 0.624 | 1·15 (0·67–1·97) | 1·07 (0·6–1·93) | |

| Treatment within 7 days of randomization | 1190/2071 (58%) | 59/120 (49%) | 0.0744 | 0·73 (0·51–1·04) | 0·78 (0·53–1·15) | |

| Anti-platelet treatment | 1928/2046 (94%) | 110/117 (94%) | 0.9226 | 0·94 (0·44–2·01) | 0·93 (0·43–2·01) |

Data are n/N (%) or mean (SD), unless otherwise stated. The combined restenosis cohort includes patients who underwent carotid artery stenting or carotid endarterectomy. The most parsimonious model indicates risk factors that were most likely to be associated with restenosis after revascularisation. Sample sizes vary for specific characteristics because data are missing for a small number of patients. HR=hazard ratio.

Adjusted for all variables.

Hypertension was defined as a blood pressure of 140/80 mm Hg or more.

Diabetes was defined by a fasting serum glucose concentration of 5 mmol/L or more or HbA1C of 42 mmol/L or more.

Dyslipidaemia was defined by concentrations of low-density lipoproteins of 2.5 mmol/L or more.

Excluding 96 patients who had a periprocedural event, participants who had restenosis or occlusion within 2 years were at greater risk for ipsilateral stroke after the periprocedural period up to the end of follow-up than were those who did not have restenosis (HR 4·37, 95% CI 1·91–10·03; p=0·0005, adjusted for age, sex, and symptomatic status). Six of 56 patients who had undergone carotid endarterectomy and had restenosis and one of 55 who had undergone carotid artery stenting had strokes after the periprocedural period. Of 1984 patients who did not have restenosis or a periprocedural event, ipsilateral strokes occurred in 30 (12 in the carotid endarterectomy group, 18 in the carotid artery stenting group).

Patients who developed restenosis were more likely to be women, hypertensive, diabetic, and dyslipidaemic than were those who did not develop restenosis, irrespective of treatment, on univariate analysis (table 3). However, smoking was associated with restenosis after carotid endarterectomy, but not after carotid artery stenting (table 3). Restenosis was more common in smokers than in non-smokers who underwent carotid endarterectomy (Kaplan-Meier estimate 10·6% [SD 2·0] vs 4·7% [0·8], log rank p=0·0012), but no difference was recorded in those who underwent carotid artery stenting (5·5% [1·5] vs 6·3% [0·9], log rank p=0·39). 43 patients had repeat revascularisation in 2 years of follow-up. Of those, 20 had previously undergone carotid artery stenting and 23 had undergone carotid endarterectomy (p=0·69). 15 patients underwent repeat revascularisation without confirmation of the presence of a restenosis by our criteria.

Table 3.

Clinical characteristics as potential predictors of restenosis according to revascularization procedure. The interaction analysis indicates a risk factor or risk factors that were associated with restenosis after one but not the other revascularization procedure. The p-value refers to the presence or absence of a significant interaction between type of revascularization procedure and a risk factor for the outcome of restenosis.

| CAS Univariate HR (95% CI) | CEA Univariate HR (95% CI) | Interaction p value* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (per difference of 10 years) | 0·90 (0·68–1·20) | 0·72 (0·54–0·95) | 0·2612 |

| Female sex | 1·42 (0·84–2·39) | 2·15 (1·30–3·53) | 0·2606 |

| White race | 0·66 (0·26–1·65) | 1·09 (0·34–3·46) | 0·5076 |

| Symptomatic | 0·66 (0·39–1·11) | 0·82 (0·50–1·34) | 0·5506 |

| Hypertension | 3·37 (1·05–10·76) | 1·55 (0·67–3·60) | 0·2896 |

| Diabetes | 2·44 (1·46–4·08) | 2·35 (1·43–3·86) | 0·9167 |

| Dyslipidemia | 5·12 (1·25–20·96) | 1·42 (0·61–3·30) | 0·1265 |

| Current smoker | 0·77 (0·41–1·42) | 2·26 (1·34–3·77) | 0·0081 |

| Previous cardiovascular disease or CABG | 1·28 (0·75–2·19) | 1·10 (0·66–1·82) | 0·6789 |

| Pre-treatment stenosis percent ≥ 70% | 1·68 (0·67–4·19) | 0·89 (0·45–1·74) | 0·2725 |

| Treatment within 7 days of randomization | 0·79 (0·47–1·33) | 0·67 (0·41–1·10) | 0·6475 |

| Anti-platelet treatment | 1·94 (0·27–14·04) | 0·78 (0·34–1·81) | 0·4059 |

CABG=Coronary artery bypass graft.

The p-value refers to the presence or absence of a significant interaction between type of revascularization procedure and a risk factor for the outcome of restenosis.

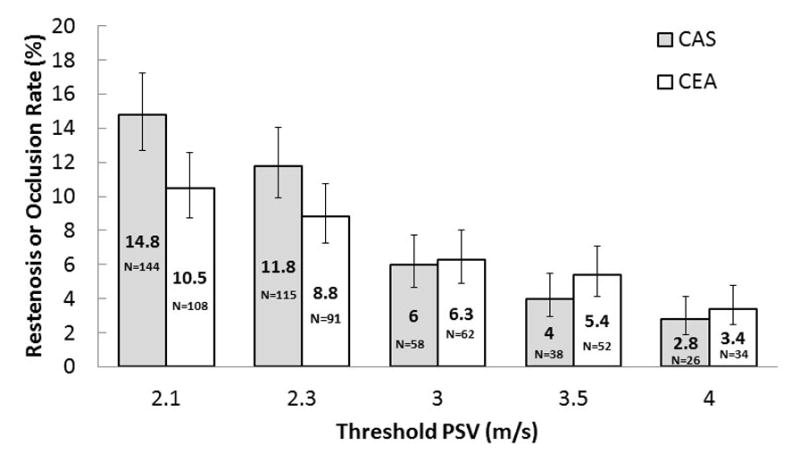

In the exploratory analysis, different thresholds of peak systolic volume yielded variable frequencies of the composite endpoint (figure 2). However, the frequencies differed by treatment received only for the 2·1 m/s threshold (log rank p=0·02; figure 2).

Figure 2.

Frequency of restenosis after carotid artery stenting or endarterectomy with different PSV thresholds

Bars indicate SE. PSV=peak systolic velocity.

DISCUSSION

Our results provide three key findings. First, carotid artery stenting and carotid endarterectomy are associated with similar frequencies of restenosis in patients with symptomatic or asymptomatic carotid stenosis. Second, female sex, diabetes, and dyslipidaemia are independent predictors of restenosis after carotid artery stenting and carotid endarterectomy, but smoking was associated with an increased likelihood of restenosis after carotid endarterectomy. Finally, restenosis is associated with an increased risk of ipsilateral stroke after both procedures.

This report analyzes two-year follow-up data on 2,191 conventional-risk patients with almost half being asymptomatic, making it the most comprehensive investigation of restenosis after carotid revascularization. Patients were treated with currently available pharmacologic, surgical, and endovascular therapies. The results are therefore readily applicable to current clinical practice. Randomized trials of medical management versus CEA did not include an assessment of restenosis.22–24 Recent randomized trials of CAS versus CEA have analyzed restenosis rates. The Stenting and Angioplasty with Protection in Patients at High Risk for Endarterectomy (SAPPHIRE) trial analyzed 260 symptomatic patients deemed high-risk for surgery.20 The Carotid and Vertebral Artery Transluminal Angioplasty Study (CAVATAS) reported on 413 conventional-risk patients of which 95% were symptomatic; of the 200 patients in their endovascular arm, only 50 received a carotid stent.3 The Stent-Protected Angioplasty versus Carotid Endarterectomy (SPACE, n=1,214) and the Endarterectomy vs. Angioplasty in Patients with Symptomatic Severe Carotid Stenosis (EVA-3S, n=507) trials also included only symptomatic patients (Table 4).4,5

Table 4.

Restenosis rates after carotid artery stenting and carotid endarterectomy as reported in randomized controlled trials comparing the two procedures in Europe and North America.

| Trial | Recruitment Period (month/year) | Definition of restenosis | Diagnostic criteria | Number of patients | Restenosis rate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Start | End | CAS | CEA | CAS | CEA | p value | |||

| CAVATAS3 | 3/1992 | 7/1997 | Restenosis ≥ 70% or occlusion | >2.1 meters/second | 50 | 213 | 16·6% over 5 years | 10·5% over 5 years | Not reported |

| SAPPHIRE20 | 8/2000 | 7/2002 | Restenosis ≥ 50% (symptomatic) and ≥ 80% (asymptomatic) | Repeat revascularization procedure | 143 | 117 | 3% over 3 years | 7·1% over 3 years | 0·08 |

| EVA-3S5 | 11/2000 | 9/2005 | Restenosis ≥70% or occlusion | ≥2.1 meters/second (CEA) and 3.0 meters/second (CAS) | 242 | 265 | 3·3% over 3 years | 2·8% over 3 years | Not significant |

| CREST1 | 12/2000 | 7/2008 | Restenosis ≥70% or occlusion | ≥3.0 meters/second | 1086 | 1105 | 6·0% over 2 years | 6·3% over 2 years | 0·58 |

| SPACE4 | 3/2001 | 2/2006 | Restenosis ≥70% or occlusion | Not specified | 541 | 522 | 11·1% over 2 years | 4·6% over 2 years | 0·0007 |

CAS=Carotid artery stenting. CEA=carotid endarterectomy. CAVATAS=Carotid and Vertebral Artery Transluminal Angioplasty Study. SAPPHIRE=Stenting and Angioplasty with Protection in Patients at High Risk for Endarterectomy. EVA-3S=Endarterectomy versus Angioplasty in Patients with Severe Symptomatic Carotid Stenosis. CREST=Carotid Revascularization Endarterectomy versus Stenting Trial. SPACE=Stent-protected Angioplasty versus Carotid Endarterectomy.

Carotid artery revascularization is a durable procedure. Our composite endpoint (diameter reduction of ≥70% or occlusion) rates over two years for CAS (6·0%) and CEA (6·3%) provide a guide with which to compare future studies. Although our initial estimates out to four years showed similar rates (6·7% for CAS and 6·2% for CEA) to those shown for two years, we prefer to focus on the two-year rates as the number of patients who had been followed to 48 months was limited such that these estimates may be unstable. Initial concerns had been expressed regarding exaggerated neointimal hyperplasia after CAS, based on the experience with coronary21 and intracranial arterial25 bare-metal stenting. This was not substantiated in CREST. Low restenosis rates after carotid stenting have also been reported in recent smaller single institution studies and randomized trials (Table 4).

We noted no difference in 2-year frequency of restenosis between the groups after adjusting for age, sex, and symptomatic status. However, the SPACE trial4 showed that restenosis occurred more frequently in 2 years after carotid artery stenting than after carotid endarterectomy (11·1% vs 4·6% of patients; p=0·0007). The CREST results offer the highest reliability and uniformity of comparison, because ultrasonography was read centrally with uniform and updated velocity criteria for the endpoint.12 In SAPPHIRE,20 reintervention was used as a surrogate for restenosis, with the assumption that the reinterventions were all done at the assigned threshold of a diameter reduction of 80% or more. In SPACE,4 restenosis interpretations reported from individual clinical centres were used. In EVA-3S,5 most ultrasound tests were done outside the participating centres, and an unspecified number of outcomes were based on written reports from clinical centres. Frequency of restenosis after 2 years remains unknown because previous studies have shown that restenosis can be reported 2 years after carotid artery stenting or carotid endarterectomy. Accordingly, the CREST cohort is being followed up to 10 years with annual ultrasonography.

CREST defined restenosis as ≥70% diameter reducing stenosis or occlusion, as has been the criterion in previously published trials.4,5,23 The clinical relevance of ≥50% stenosis is not established, and we did not seek to identify this subset of patients. Duplex ultrasound velocity thresholds for deriving estimates of percent stenosis in native carotid arteries are well-established and validated.26,27 The CREST definition of ≥3·0 m/s is based on a comparison of over 500 duplex ultrasound and anatomic comparative imaging studies. The SPACE investigators used a lower peak systolic velocity threshold4—2·1 m/s—which could explain why the frequency of restenosis was higher than in EVA-3S,5 in which a threshold of 3·0 m/s was used. As the threshold was reduced in our exploratory analysis, the frequency of restenosis increased more in patients who had undergone carotid artery stenting than in those who had had carotid endarterectomy. However, we noted a significant difference only with the 2·1 m/s threshold.

Previous trials have identified risk factors for restenosis on the basis of assessments of patients after carotid artery stenting and carotid endarterectomy as a combined group. In CREST, patients with restenosis were most likely to be women with diabetes and dyslipidaemia. No previous randomised trial has identified an increased likelihood for women to develop restenosis after carotid revascularisation. Previous single-institution studies of carotid artery stenting28 and larger studies of coronary and intracranial arteries25 have implied that diabetes is a risk factor for recurrent stenosis after carotid stenting. This association has not been identified in other trials of carotid artery stenting or carotid endarterectomy. The SAPPHIRE20 and SPACE4 trials did not include assessments of risk factors. Smoking in the CAVATAS trial3 and increasing age in EVA-3S5 were shown to predict restenosis.

The injury patterns and biologic effects of CAS and CEA are likely quite different. It is possible that these are impacted differently by patient clinical factors. We found that the risk factors for restenosis were generally similar for CAS and for CEA and included female sex, diabetes, and dyslipidemia. However, smoking was associated with a higher risk of restenosis after CEA but not after CAS. A differential influence of risk factors on restenosis after CAS compared to CEA has not been identified in prior trials.

Our results indicate that restenosis was associated with an increased risk of ipsilateral stroke after CAS or CEA. The occurrence of both stroke and restenosis was identified at the time of an assigned follow-up. Therefore, it cannot be stated with certainty whether the restenosis developed before or after the stroke. Furthermore, restenosis is cumulative and the result of progressive accumulation of neointimal or atherosclerotic material over time. Based on our protocol we can clearly define the time of diagnosis of restenosis and not the time of development of restenosis. A limitation of the study is that the results do not allow inference with regard to the potential need for repeat CAS or CEA to address the increased risk of stroke. Repeat revascularization for restenosis was infrequent. Because the threshold restenosis at which these procedures were performed was not protocol-driven in CREST, some patients received re-intervention without an established diagnosis of high-grade (≥70% diameter reducing) stenosis at the Core Laboratory. The method of revascularization was not protocol-driven and ranged from repeat endarterectomy, to balloon angioplasty or repeat stenting.

Panel: Research in context.

Systematic review

We searched PubMed for reports published in English between Jan 1, 1990, and April 30, 2012, with the terms “clinical trials”, “carotid endarterectomy”, “carotid stenting”, “restenosis”, and “recurrent stenosis”. References within these reports were also checked for additional related citations. We manually reviewed the reports and identified those of multicentre randomized trials with available information about enrolment and outcomes during follow-up. We identified four trials of restenosis in patients who had undergone carotid artery stenting or carotid endarterectomy.3–5,20 We noted that published trials have varying conclusions (table 4): they have shown no difference in restenosis, an increase in frequency after endarterectomy, or an increase in frequency after stenting. However, bare-metal stenting in the coronary artery is known to be associated with increased rates of recurrent stenosis.21

Interpretation

On the basis of the results from the previous trials,3–5,20 we did this secondary analysis of CREST with the hypothesis that carotid artery stenting would result in a higher rate of restenosis than would carotid endarterectomy. The large number of patients included in our study—many of whom were asymptomatic—means that it is the most comprehensive analysis of restenosis after carotid revascularisation. We have shown that the procedures are associated with similar rates of restenosis. Our results provide reassurance that carotid revascularisation is durable, and identify subsets of patients that might benefit from close surveillance for recurrence.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (grant NS038384) and Abbott Vascular Solutions.

CREST Principal Investigators (in order of number of participants randomized)

Wayne Clark - Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, OR

William Brooks - Central Baptist Hospital, Lexington, KY

Ariane Mackey - Centre Hospitalier Affilié universitaire de Québec-Hôpital de l’Enfant-Jésus, Québec City, QC Canada

Michael Hill - University of Calgary/Foothills Medical Centre, Calgary, AB Canada

Pierre Leimgruber - Deaconess Medical Center/Northwest Cardiovascular Research Institute, Spokane, WA

Vito Mantese - St. John’s Mercy Medical Center, St. Louis, MO

Carlos Timaran - University of Texas Southwestern Medical School, Dallas, TX

Nelson Hopkins - SUNY at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY

David Chiu - Methodist Hospital, Houston, TX

Richard Begg - Tri-State Medical Group, Beaver, PA

Zafar Jamil - St. Michael’s Medical Center, Newark, NJ

Robert Hye - Kaiser Permanente - San Diego Medical Center, San Diego, CA

Bart Demaerschalk - Mayo Clinic Arizona, Scottsdale, AZ

O.W. Brown - Beaumonts Hospitals, Royal Oak, MI

Gary Roubin - Lenox Hill Hospital, New York, NY

Donald Heck - Forsyth Medical Center, Winston-Salem, NC

Richard Farb - Toronto Western Hospital, Toronto, ON Canada

Irfan Altafullah - North Memorial Medical Center, Golden Valley, MN

Gary Ansel - MidWest Cardiology Research Foundation, Columbus, OH

Albert Sam, II - Vascular Specialty Associates, Baton Rouge, LA

Nicole Gonzales - University of Texas Medical School, Houston, TX

Peter Soukas - St. Elizabeth’s Medical Center, Boston, MA

Lawrence Wechsler - University of Pittsburgh Medical Center/Shadyside Hospital and Presbyterian Hospital, Pittsburgh, PA

Daniel Clair - Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH

Mark Reisman - Swedish Medical Center, Seattle, WA

John Eidt - University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences/Central Arkansas Veteran’s Healthcare System, Little Rock, AR

Steven Orlow -Northern Indiana Research Alliance, Fort Wayne, IN

James Burke - Intermountain Medical Center, Salt Lake City, UT

Mahmoud Malas - Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions, Baltimore, MD

Michael Rinaldi - Sanger Heart and Vascular Institute, Charlotte, NC

Kenneth Rosenfield - Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA

Charles Sternbergh, III - Ochsner Health System, New Orleans, LA

Richard McCann - Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC

Charles O’Mara - Mississippi Baptist Medical Center, Jackson, MS

Albert Hakaim - Mayo Clinic Florida, Jacksonville, FL

Barry Katzen - Baptist Cardiac and Vascular Institute, Miami, FL

Robert Spetzler - Barrow Neurological Institute, Phoenix, AZ

Anthony Pucillo - Westchester Medical Center, Valhalla, NY

James Elmore - Geisinger Medical Center, Danville, PA

William Jordan - University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL

David Lew - Leesburg Regional Medical Center, Leesburg, FL

Richard Powell - Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, NH

Robert Bulas - The Christ Hospital, Cincinnati, OH

Bryan Kluck - Lehigh Valley Hospital, Allentown, PA

Joseph Rapp - San Francisco VA Medical Center, San Francisco, CA

Gregory Mishkel - Prairie Education and Research Cooperative, Springfield, IL

Fred Weaver - University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA

Munier Nazzal - University of Toledo Medical Center, Toledo, OH

Craig Narins - University of Rochester Medical Center, Rochester, NY

Robert Molnar - Michigan Vascular Research Center, Flint, MI

Mark Eskandari - Northwestern Memorial Hospital, Chicago, IL

Herbert Aronow - Michigan Heart & Vascular Institute, Ann Arbor, MI

Fayaz Shawl - Washington Adventist Hospital, Takoma Park, MD

Robert Rosenwasser - Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, PA

Hollace Chastain - Parkview Research Center, Fort Wayne, IN

Malcolm Foster - Baptist Hospital West, Inc., Knoxville, TN

Rodney Raabe - Providence Medical Research Center, Spokane, WA

David Pelz - London Health Sciences Centre, London, ON Canada

Grant Stotts - Ottawa Hospital, Ottawa, ON Canada

Harry Cloft - Mayo Clinic Rochester, Rochester, MN

Louis Heller - St. Joseph’s Hospital of Atlanta, Atlanta, GA

Bhagat Reddy - Piedmont Hospital/Fuqua Heart Center, Atlanta, GA

Kim Hodgson - Southern Illinois School of Medicine, Springfield, IL

Ken Fraser - OSF Saint Francis Medical Center, Peoria, IL

William Gray - Columbia University Medical Center/New York Presbyterian Hospital, New York, NY

Alexander Shepard - Henry Ford Hospital, Detroit, MI

Walter Montanera - St. Michael’s Hospital, Toronto, Canada

Wes Moore - University of California, Los Angeles, CA

Elliot Chaikof - Emory University Hospital/Atlanta VAMC, Atlanta, GA

Sarah Johnson - Cardiovascular Research Foundation/Cardiovascular Associates, Elkgrove, IL

Richard Zelman - Cape Cod Research Institute, Hyannis, MA

Avery Evans - University of Virginia Health System, Charlottesville, VA

David Burkart - St. Joseph Medical Center, Kansas City, MO

Dennis Bandyk - University of South Florida, Tampa, FL

Percy Karanjia - Marshfield Clinic, Marshfield, WI

Jamal Zarghami - Providence Hospital and Medical Centers, Southfield, MI

Adam Arthur - Baptist Memorial Hospital, Memphis, TN

Manish Mehta - Vascular Interventional Project, Inc., Albany, NY

Anthony Comerota - Jobst Vascular Center, Toledo, OH

Kannan Natarajan - St. Vincent Hospital, Indianapolis, IN

Jay Howington - St. Joseph/Candler Health System, Savannah, GA

Daniel Selchen - Trillium Health Centre, Mississauga, ON Canada

Marc Schermerhorn - Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, MA

Steven Laster - St. Luke’s Hospital, Kansas City, MO

Mark Sanz - St. Patrick Hospital, Missoula, MT

Eric Lopez del Valle - Morton Plant Hospital, Clearwater, FL

Joseph Andriole - Orlando Regional Healthcare, Orlando, FL

Andrew Ringer - University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH

John Martin - Anne Arundel Medical Center, Annapolis, MD

Randy Guzman - University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, MB Canada

Philip Teal - Vancouver General Hospital, Vancouver BC, Canada

Frank Hellinger - Florida Hospital, Orlando, FL

George Petrossian - St. Francis Hospital, Roslyn, NY

Mark Bates - Charleston Area Medical Center, Charleston WV

Joseph Mills - University of Arizona College of Medicine, Tucson, AZ

Michael Golden - Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA

Ashraf Mansour - Butterworth Hospital, Grand Rapids, MI

Andrew MacBeth - St. Joseph’s Medical Center, Stockton, CA

L.A. Iannone - Iowa Heart Center, Des Moines, IA

Kimberly Hansen -Wake Forest University Health Sciences, Winston Salem, NC

Jose Biller - Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood, IL

John Shuck - Christiana Care Health Services, Newark, DE

Pierre Gobin -Weill Cornell Medical College of New York Presbyterian Hospital, New York, NY

Kent Dauterman - Rogue Valley Medical Center, Medford, OR

Jim Melton - Oklahoma Foundation for Cardiovascular Research, Oklahoma City, OK

Daniel Benckart - Allegheny General Hospital, Pittsburgh, PA

Walter Lesley - Scott & White Memorial Hospital, Temple, TX

Michael Belkin - Brigham & Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA

Tanvir Bajwa - St. Luke’s Medical Center, Milwaukee, WI

Subbarao Myla - Hoag Memorial Hospital, Newport Beach, CA

Jeffrey Snell - Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, IL

Harish Shownkeen - Central DuPage Hospital, Winfield, IL

Alex Abou-Chebl - University of Louisville, Louisville, KY

Footnotes

Authors’ contributions:

BKL wrote the first version of the manuscript. JHV did the statistical analysis. KWB and TGB contributed to the writing of the manuscript. All authors commented on and helped with revisions to the manuscript.

Author conflicts of interest information: B.K. Lal: None. K.W. Beach: None. G.S. Roubin: Royalties, Abbott Vascular and Cook, Inc. H.L. Lutsep: Consultant/Advisory Board, Gore. W.S. Moore: Consultant/Advisory Board, WL Gore. M.B. Malas: None. D. Chiu: None. N.R. Gonzales: None. J.L. Burke: None. M. Rinaldi: Consultant/Advisory Board, Abbott, Cordis, and Boston Scientific. J.R. Elmore: None. F.A. Weaver: None. C.R. Narins: None. M. Foster: Honoraria, Abbott Vascular. K. Hodgson: None. A.D. Shepard: None. J.F. Meschia: None. R.O. Bergelin: None. J.H. Voeks: None. G. Howard: Support from Abbott Vascular for preparation of FDA materials. T.G. Brott: None.

References

- 1.Brott TG, Hobson RW, II, Howard G, et al. Stenting versus endarterectomy for treatment of carotid-artery stenosis. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:11–23. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0912321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lal BK, Hobson RWII, Goldstein J, et al. In-stent recurrent stenosis after carotid artery stenting: life table analysis and clinical relevance. J Vasc Surg. 2003;38:1162–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2003.08.021. discussion 1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bonati LH, Ederle J, McCabe DJH, et al. Long-term risk of carotid restenosis in patients randomly assigned to endovascular treatment or endarterectomy in the Carotid and Vertebral Artery Transluminal Angioplasty Study (CAVATAS): long-term follow-up of a randomised trial. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8:908–17. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70227-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eckstein H-H, Ringleb P, Allenberg J-R, et al. Results of the Stent-protected Angioplasty versus Carotid Endarterectomy (SPACE) study to treat symptomatic stenoses at 2 years: a multinational, prospective, randomised trial. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7:893–902. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70196-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arquizan C, Trinquart L, Touboul P-J, et al. Restenosis is more frequent after carotid stenting than after endarterectomy. Stroke. 2011;42:1015–20. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.589309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DeGroote RD, Lynch TG, Jamil Z, Hobson RW., 2nd Carotid restenosis: long-term noninvasive follow-up after carotid endarterectomy. Stroke. 1987;18:1031–6. doi: 10.1161/01.str.18.6.1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lattimer CR, Burnand KG. Recurrent carotid stenosis after carotid endarterectomy. Br J Surg. 1997;84:1206–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Keagy BA, Edrington RD, Poole MA, Johnson G. Incidence of recurrent or residual stenosis after carotid endarterectomy. Am J Surg. 1985;149:722–5. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(85)80173-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sheffet AJ, Roubin G, Howard G, et al. Design of the Carotid Revascularization Endarterectomy vs. Stenting trial (CREST) Int J Stroke. 2010;5:40–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4949.2009.00405.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lal BK, Brott TG. The Carotid Revascularization Endarterectomy vs. Stenting Trial completes randomization: lessons learned and anticipated results. J Vasc Surg. 2009;50:1224–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2009.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hopkins LN, Roubin GS, Chakhtoura EY, et al. The Carotid Revascularization Endarterectomy versus Stenting Trial: credentialing of interventionalists and final results of lead-in phase. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2010;19:153–162. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beach KW, Bergelin RO, Leotta DF, et al. Standardized ultrasound evaluation of carotid stenosis for clinical trials: University of Washington Ultrasound Reading center. Cardiovasc Ultrasound. 2010;8:39. doi: 10.1186/1476-7120-8-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Primozich JP. Extracranial arterial system. In: Strandness DE, editor. Duplex scanning in vascular disorders. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2002. pp. 211–228. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lal BK, Hobson RW, II, Tofighi B, Kapadia I, Cuadra S, Jamil Z. Duplex ultrasound velocity criteria for the stented carotid artery. J Vasc Surg. 2008;47:63–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2007.09.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Setacci C, Chisci E, Setacci F, Iacoponi F, de Donato G. Grading carotid intrastent restenosis. Stroke. 2008;39:1189–1196. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.497487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.AbuRahma AF, Abu-Halimah S, Bensenhaver J, et al. Optimal carotid duplex velocity criteria for defining the severity of carotid in-stent restenosis. J Vasc Surg. 2008;48:589–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2008.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhou W, Felkai DD, Evans M, et al. Ultrasound criteria for severe in-stent restenosis following carotid artery stenting. J Vasc Surg. 2008;47:74–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2007.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chi Y-W, White CJ, Woods TC, Goldman CK. Ultrasound velocity criteria for carotid in-stent restenosis. Catheter and Cardiovasc Interv. 2007;69:349–54. doi: 10.1002/ccd.21032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lal BK, Hobson RW, II, Goldstein J, Chakhtoura EY, Duran WN. Carotid artery stenting: is there a need to revise ultrasound velocity criteria? J Vasc Surg. 2004;39:58–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2003.10.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gurm HS, Yadav JS, Fayad P, et al. Long-term results of carotid stenting versus endarterectomy in high-risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1572–79. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0708028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Antoniucci D, Valenti R, Santoro GM, et al. Restenosis after coronary stenting in current clinical practice. Am Heart J. 1998;135:510–18. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(98)70329-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial Collaborators. Beneficial effect of carotid endarterectomy in symptomatic patients with high-grade carotid stenosis. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:445–53. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199108153250701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Executive Committee for the Asymptomatic Carotid Atherosclerosis Study Endarterectomy for asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis. JAMA. 1995;273:1421–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.European Carotid Surgery Trialists’ Collaborative Group. Randomised trial of endarterectomy for recently symptomatic carotid stenosis: final results of the MRC European Carotid Surgery Trial (ECST) Lancet. 1998;351:1379–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.SSYLVIA Study Investigators. Stenting of Symptomatic Atherosclerotic Lesions in the Vertebral or Intracranial Arteries (SSYLVIA): study results. Stroke. 2004;35:1388–92. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000128708.86762.d6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grant EG, Benson CB, Moneta GL, et al. Carotid artery stenosis: gray-scale and Doppler US diagnosis—Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound Consensus Conference. Radiology. 2003;229:340–6. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2292030516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lal BK, Kaperonis EA, Cuadra S, Kapadia I, Hobson RW., II Patterns of in-stent restenosis after carotid artery stenting: classification and implications for long-term outcome. J Vasc Surg. 2007;46:833–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2007.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abizaid A, Kornowski R, Mintz GS, et al. The influence of diabetes mellitus on acute and late clinical outcomes following coronary stent implantation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;32:584–9. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00286-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]