Abstract

Objectives

To estimate the proportion of rotavirus gastroenteritis (RVGE) among children aged less than 5 years who had been diagnosed with acute gastroenteritis (AGE) and admitted to hospitals and emergency rooms (ERs). The seasonal distribution of RVGE and most prevalent rotavirus (RV) strains was also assessed.

Design

A cross-sectional hospital-based surveillance study.

Setting

5 reference paediatric hospitals across Abidjan.

Participants

Children aged less than 5 years, who were hospitalised/visiting ERs for WHO-defined AGE, were enrolled. Written informed consent was obtained from parents/guardians before enrolment. Children who acquired nosocomial infection were excluded from the study.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

The proportion of RVGE among AGE hospitalisations and ER visits was expressed with 95% exact CI. Stool samples were collected from all enrolled children and were tested for the presence of RV using an enzyme immunoassay. RV-positive samples were serotyped using reverse transcriptase-PCR.

Results

Of 357 enrolled children (mean age 13.6±11.14 months), 332 were included in the final analyses; 56.3% (187/332) were hospitalised and 43.7% (145/332) were admitted to ERs. The proportion of RVGE hospitalisations and ER visits among all AGE cases was 30.1% (95% CI 23.6% to 37.3%) and 26.9% (95% CI 19.9% to 34.9%), respectively. Ninety-five children (28.6%) were RV positive; the highest number of RVGE cases was observed in children aged 6–11 months. The number of GE cases peaked in July and August 2008; the highest percentage of RV-positive cases was observed in January 2008. G1P[8] wild-type and G8P[6] were the most commonly detected strains.

Conclusions

RVGE causes substantial morbidity among children under 5 years of age and remains a health concern in the Republic of Ivory Coast, where implementation of prevention strategies such as vaccination might help to reduce disease burden.

Keywords: Virology, Infectious Diseases

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Our study was conducted in large city-based paediatric hospitals and our findings are, therefore, likely to be representative of the whole population.

Our systematic approach for enrolment allowed the easy identification of acute gastroenteritis (AGE) cases.

Our study enrolled only a proportion of all reported AGE cases and only severe cases were included.

Introduction

Wild-type rotavirus (RV) causes approximately 111 million gastroenteritis (GE) episodes, 25 million clinic visits, 2 million hospitalisations and over 453 000 deaths each year among children younger than 5 years of age.1 2 It has been reported that RV mortality is highest among the low-income countries of Asia, Africa and Latin America.3 A systematic review and meta-analysis of published studies in 2009 found that the overall mortality rate associated with RV infection in children under 5 years of age in sub-Saharan Africa was 243.3 deaths/100 000 children (95% CI 187.6 to 301.7).4 Globally, RV infection rates are also highest among younger children, with approximately 95% children experiencing at least one episode of RVGE by the time they reach 5 years of age.5

RVGE is characterised by fever, diarrhoea and vomiting, leading to severe dehydration and increased hospitalisation. Over 90% of children with RVGE suffer from dehydration-associated mortality due to diarrhoea and associated vomiting.6–8 It has been suggested that RV infections are more common during the cooler months of the year and that RVGE disease burden is similar in high-income and low-income nations.1 However, due to malnutrition and lack of access to appropriate treatment facilities, it is the children from the low-income countries who die more frequently.1

As improvements in hygiene and sanitation have not been accompanied by reductions in the incidence of RV-associated diseases,9 vaccination against RV is, therefore, considered as a public health priority for low-income nations.10 The introduction of RV vaccination could have significant benefits for children aged less than 3 years, and might help to reduce diarrhoea-associated childhood morbidity and mortality in low-income countries and RV-related hospitalisation in high-income countries.11 12

The most common globally circulating RV serotypes associated with RVGE are G1, G2, G3 and G4.13 In addition, G9 has emerged over the past decade as a globally important serotype.14 Together, these serotypes are responsible for 95% of worldwide paediatric RVGE cases.15

The epidemiology of RV infection has been followed in several small studies conducted in Abidjan in the Republic of Ivory Coast,16–21 but recent data for this region are limited. Nevertheless, data on RVGE disease, the number of hospitalisations and the number of emergency room (ER) visits following acute GE (AGE) are critical to formulate effective policies to control RV-related AGE and are important to fully determine the need for RV vaccines and the possible impact of their introduction.

This study was designed to estimate the proportion of RVGE among children younger than 5 years of age who were diagnosed with AGE and admitted to hospitals and ERs in the Republic of Ivory Coast. The seasonal distribution of RVGE and the prevalent RV types were also studied.

Methods

Study design

This cross-sectional, hospital-based surveillance study was conducted across five reference paediatric hospitals in Abidjan, the Republic of Ivory Coast between December 2007 and February 2009. The study was conducted in accordance with Good Clinical Practice, Declaration of Helsinki (V.1996) and applicable local regulations. Written informed consent was obtained from parents/guardians before children were enrolled.

Children presenting AGE were identified by checking hospital and ER logbooks. Male or female children aged less than 5 years, who were hospitalised or visited ER for AGE (≥3 looser than normal stools per day with or without ≥2 episodes of vomiting within 24 h), were included in the study. Children were excluded if they acquired AGE by possible nosocomial infection (within 12 h after hospital admission).

Unique study numbers were assigned sequentially to all enrolled children in order to maintain their confidentiality. Parents/guardians were interviewed and medical records were reviewed by the site staff to complete the study questionnaire and/or case report form. Information including demography (date of birth, gender, height and weight, nutritional status and area of residence), admission date and diagnosis at admission, date of discharge and administration of oral and/or intravenous rehydration/antibiotics were recorded and encoded in the study database. Details such as body temperature, duration of diarrhoea or vomiting, treatment and behavioural symptoms were also recorded. The severity of RVGE was defined according to the Vesikari Scale (mild: score <7; moderate: 7–10 and severe: ≥11).22

Stool samples collected within 4–10 days of the onset of GE from all enrolled children as part of the study procedures were labelled, stored at a temperature of −20°C to −70°C and then transported to the Pasteur Institute, Abidjan, within 72 h of collection for testing. RV testing was performed using the IDEIA rotavirus kit (DAKO Ltd, Cambridgeshire, UK) provided by the regional laboratory (Ivory Coast National Laboratory for Rotavirus, affiliated to the WHO regional reference laboratory located in Accra, Ghana (West Africa), at the Noguchi Memorial Institute for Medical Research). A random subset of RV-positive stool samples were subsequently tested using reverse transcriptase-PCR of the VP7 and VP4 genes followed by reverse hybridisation on a strip at the DDL Diagnostic Laboratory (Rijswijk, The Netherlands) to identify G and P genotypes and to differentiate the presence of wild-type G1 RV from the vaccine strain virus.23 A visible pattern is observed on the strip after hybridisation which is specific to each genotype. As a complementary tool, sequence analysis was performed to identify the genotypes for samples that yielded an unclear pattern that could not be recognised. The resulting sequence was analysed by BLAST search against the GenBank database to determine the RV genotype.23

Analyses

All children meeting the predefined eligibility criteria were included in the final analyses.

The occurrence of severe dehydrating RVGE (based on the Vesikari Scale22) administered treatment (including intravenous rehydration), duration of hospitalisation and outcome were all reported, together with the seasonal distribution of RVGE and the occurrence of RV types.

All statistical analyses were performed using Statistical Analysis System (SAS) V.9.2 and the graphs were generated using Microsoft Excel. Categorical data such as gender, seasonal distribution and disease severity were presented as proportions with one decimal. Burden of GE/RVGE among hospitalisations/ER visits was expressed as proportions with their 95% exact CI. Exploratory analyses of estimation of the crude OR were performed using univariate logistic regression considering RV status outcome variable. Clinical characteristics and outcome at discharge were considered as the confounding factors for this analysis. Univariate logistic regression was used to estimate the association between outcome at discharge as the dependent variable and RV status/nutritional status as the independent factor. Nutritional status was derived using the weight-for-age Z-scores based on the WHO child growth standards. Associations between these derived nutritional status and the RV positivity were analysed using the χ2 test with 95% exact CI. Association between the clinical characteristics before/during hospitalisation and RV status were analysed using χ2 and fisher's exact test with 95% exact CI.

Results

Demographic characteristics

A total of 1330 children (917 hospitalised and 413 visiting ER) presenting AGE were identified from hospital logs. Of these, 357 children were enrolled into the study. Informed consent was not collected for 973 children, due to parent refusal, non-collection of samples and failure of the surveillance to capture the cases. The mean age (SD) of the enrolled children was 13.6 months (±11.14 months; table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of enrolled children (N=357)

| Characteristics | Parameters | Total (N*=357) |

Emergency room (N=161) |

Hospitalised (N=196) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N† | Per cent‡ | n | Per cent | n | Per cent | ||

| Age (months) | N | 357 | – | 161 | – | 196 | – |

| Mean | 13.6 | – | 13.7 | – | 13.5 | – | |

| SD | 11.14 | – | 11.39 | – | 10.96 | – | |

| Gender | Female | 152 | 42.6 | 69 | 42.9 | 83 | 42.3 |

| Male | 205 | 57.4 | 92 | 57.1 | 113 | 57.7 | |

*Number of children.

†Number of children in a given category.

‡n/N×100.

A total of 332 children were included in the final analysis; 25 were excluded due to not meeting the inclusion/exclusion criteria (protocol violation) in two cases and failure to either collect or analyse the stool samples for RV in the remaining 23 children.

Among those included in the final analysis, 56.3% (187/332) children had been hospitalised and the remaining 43.7% (145/332) had visited an ER.

Proportion of GE and RVGE hospitalisations

The proportion of all AGE-related hospitalisations and ER visits that were diagnosed with RVGE was 30.1% (n=56; 95% CI 23.6% to 37.3%) and 26.9% (n=39; 95% CI 19.9% to 34.9%), respectively.

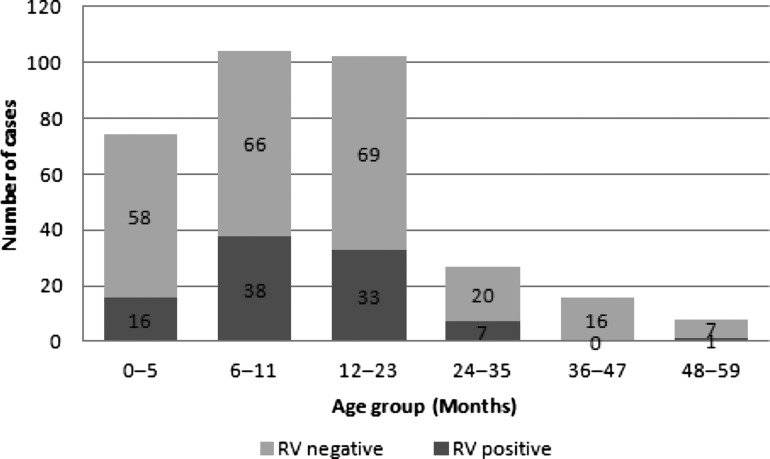

Most of the children hospitalised and visiting the ER due to AGE corresponded to children under 2 years of age (84.8% and 84.5%, respectively). The number of RV-positive and RV-negative children stratified by age is shown in figure 1. Ninety-five children (28.6%) were RV positive, of whom over 80% were aged less than 24 months. The highest number of RVGE cases was seen in children aged 6–11 months (40% (38/95); figure 1).

Figure 1.

Distribution of GE cases by RV status by age groups (N=332). GE, gastroenteritis; RV, rotavirus.

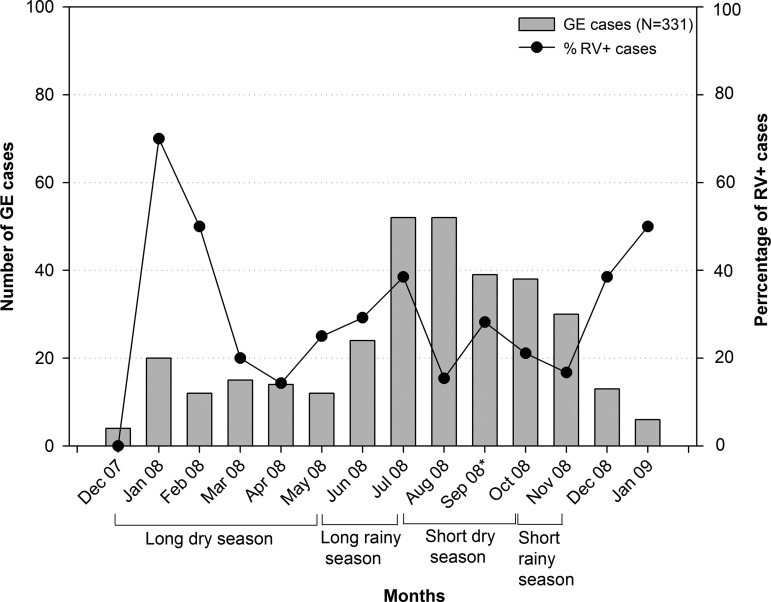

The seasonal distribution of RV-attributable GE hospitalisation is shown in figure 2. The number of GE cases was highest in July and August 2008 and the percentage of RV-positive cases was highest in January 2008.

Figure 2.

Seasonality of acute GE and RVGE hospitalisations (N=331). GE, gastroenteritis; RV, rotavirus.

Clinical characteristics of GE and RVGE hospitalisations

Among RV-positive and RV-negative children, severe GE (score ≥11 on the Vesikari Scale) was recorded in 64.2% (61/95) and 55.5% (131/236) of children before hospitalisation, respectively (table 2).

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of children by RV status (N=331)

| Characteristics | RV positive (N*=95) n† (%‡) | RV negative (N=236) n (%) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Severity§ before hospitalisation | |||

| Mild (<7) | 6 (6.3) | 27 (11.4) | 0.2300¶ |

| Moderate (7–10) | 28 (29.5) | 78 (33.1) | |

| Severe (≥11) | 61 (64.2) | 131 (55.5) | |

| Symptoms before hospitalisation | |||

| Diarrhoea | 95 (100.0) | 235 (99.6) | 1.0000** |

| Vomiting | 81 (85.3) | 170 (72.0) | 0.0037** |

| Fever | 44 (46.3) | 116 (49.2) | 0.8557¶ |

| Classification of nutrition | |||

| Overweight | 5 (5.3) | 8 (3.4) | 0.1981¶ |

| Adequate (normal) | 66 (69.5) | 152 (64.4) | |

| Moderately malnourished | 15 (15.8) | 32 (13.6) | |

| Severely malnourished | 9 (9.5) | 44 (18.6) | |

| Outcome at discharge | |||

| Recovered | 27 (28.4) | 40 (16.9) | 0.0145** |

| Ongoing GE | 68 (71.6) | 184 (78.0) | |

| Transferred | 0 (0.0) | 4 (1.7) | |

| Died | 0 (0.0) | 8 (3.4) | |

One child was excluded from analysis as RV status was not determined.

Nutritional status was derived using the weight-for-age Z-scores (WAZ).

*Number of children.

†Number of children in a given category.

‡n/N×100.

§Severity using the 20-point Vesikari Scale.

¶χ2 p Value.

**Fisher's exact test p Value.

GE, gastroenteritis; RV, rotavirus.

The percentage of children recording GE-associated symptoms (diarrhoea, vomiting and fever) was similar across RV-positive and RV-negative groups before hospitalisation. However, a significant (p=0.0037) association between vomiting and RV-positive status was observed before hospital admission (table 2).

Nutritional status based on weight indicated that adequately and moderately malnourished children were distributed similarly across RV-positive and RV-negative groups. However, a higher number of severely malnourished children was observed in the RV-negative group (table 2).

Oral rehydration was the most commonly used treatment for GE in RV-positive and RV-negative groups (70.5% and 75.8%, respectively), followed by intravenous rehydration therapy (54.7% and 53%, respectively).

At discharge, the majority of children among RV-positive and RV-negative groups (71.6% (68/95) and 78% (184/236), respectively) had ongoing GE. Eight RV-negative children (3.4%) died, of whom all but one (87.5% (7/8)) were severely malnourished. The unadjusted OR estimate indicated that severely malnourished children had 22.2 (95% CI 2.5 to 198.8) times higher risk of dying as compared with children with adequate nutritional status (p=0.0056; table 2).

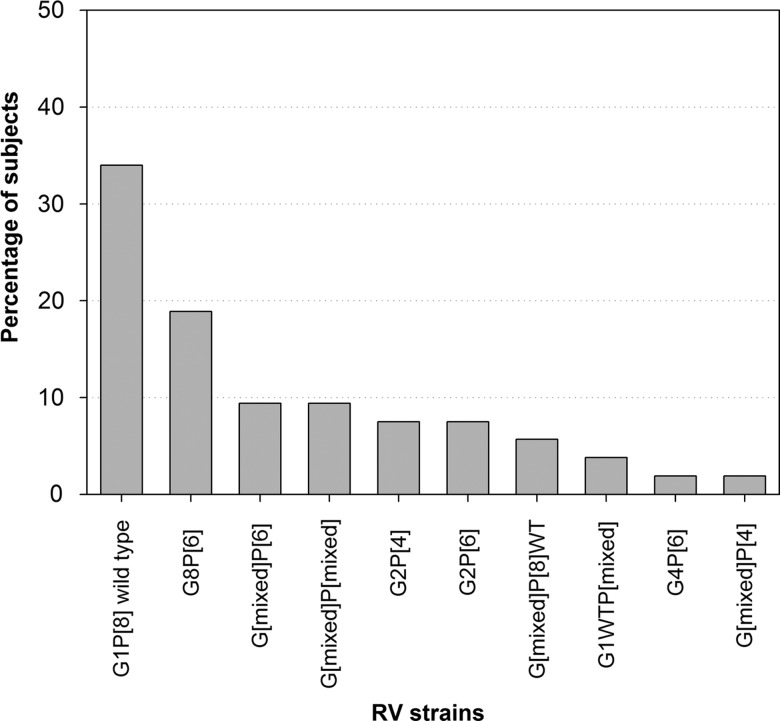

RV-type distribution

Fifty-three of 95 RV-positive stool samples were assessed for RV type in this study. The most prevalent RV types were G1P[8] wild-type (34% (18/53)) and G8P[6] (18.9% (10/53)). Mixed RV types were detected in 30.2% (16/53). The RV vaccine strain (G1P[8] vaccine strain) was not detected in any sample. The other detected RV types are shown in figure 3.

Figure 3.

Distribution of RV G and P types (N=331). RV, rotavirus.

Discussion

This study into RVGE disease burden found that RV infection is the primary cause of hospitalisation due to GE in children aged less than 5 years in the Republic of Ivory Coast.

We identified RV in 30.1% and 26.9% children either hospitalised or visiting an ER for AGE, respectively. This is consistent with an earlier epidemiological study in Abidjan that demonstrated the general prevalence of RVGE in children younger than 5 years to be 27.9% between 1997 and 2000.21 In addition, a review of published studies (1975–1992) of RVGE in Africa detected RV in 24–29% of children hospitalised for diarrhoea.9

In the present study, RV disease burden was predominantly observed among young children (over 90% (87/95) were aged up to 23 months), which is consistent with previous studies conducted across the African continent.9 A study conducted in Nigeria showed that over 90% of RVGE-positive cases were observed in children aged less than 2 years24 and two independent studies conducted in Egypt (1995–1996)25 and Libya (October 2007–September 2008)26 indicated that the incidence of RVGE was highest among children aged 6–11 months; all comparable to the results of the present study.

As observed in previous studies conducted in sub-Saharan Africa between 1975 and 1992,9 most GE cases in this study were observed between July and August 2008.

Almost all children who died following AGE in this study were severely malnourished, indicating the importance of nutritional status in potentially determining the outcome of AGE. Previous reports substantiate these findings, where malnourishment has been associated with a considerable risk of diarrhoea-associated mortality.27 28

The circulation of mixed RV types in the African countries has been previously reported.29 30 In this study, although wild-type G1P[8] was the most commonly detected (34% (18/53)) RV type, several (30.2% (16/53)) mixed RV types were detected. The proportion of mixed RV types observed in this study is comparable to that reported by the WHO's RV surveillance in the African region.31 In this report, nearly 42% of the circulating RV types during 2006–2009 comprised mixed RV types.31

There is no available antiviral therapy for RV infection,32 and RVGE management predominantly includes fluid and electrolyte replacement and improvements in sanitation and water supply.33 Antibiotic treatment is not justified during RVGE and its use is limited to cases with documented bacterial coinfection. However, it has been suggested that improvements in hygiene and provision of safe water may not be as effective in the prevention of RVGE as they are to GE due to other causes.33

Previous studies have established that RV vaccination confers protection against severe RVGE and has helped relieve the global burden of this disease.34–37 These effects have been observed in similar settings in Asia, Africa and Latin America.29 38 39 The efficacy of RV vaccines against severe RVGE has been found to be 59% in South Africa and Malawi40 and 64% in Kenya, Ghana and Mali.41 RV vaccination may, therefore, represent the most effective primary public health intervention against RVGE. Indeed in 2009, the WHO recommended the inclusion of RV vaccines in the routine childhood vaccine programmes of all countries.42 RV vaccines are available in the private sector in the Republic of Ivory Coast, but no RV vaccine is currently included in the universal mass vaccination programme.

Data presented in this study highlight the magnitude of RV-associated disease burden and might allow policymakers to determine the need to implement prevention strategies in the Republic of Ivory Coast. Indeed, the inclusion of a RV vaccine, as a prevention strategy, might help to reduce the burden of AGE and AGE-associated hospitalisations.

The results of this study need to be interpreted in the light of several strengths and limitations. Among the strengths, the systematic approach followed in this study to identify children by checking hospital and ER logbooks enabled easy identification of AGE cases using standard case definitions. Second, the study was conducted in reference hospitals seeing over 1300 AGE cases annually, which complies with the recommendations of WHO's generic protocol for hospital-based RVGE in children.43 By including multiple centres, these data more closely represent the local population. In addition, the quality check processes performed on the laboratory tests of RV-positive samples provide credibility to the results.

However, the study does have limitations. As a large number of children who presented with GE were not enrolled and tested for RV, the possibility of selection bias might be considered. Our reported prevalence of RVGE might have been affected by selecting only severe GE cases with more severe disease characteristics, including longer hospital stays. Nonetheless, this study provides a realistic picture of the role of RV among more severe cases of RVGE, which incur substantial direct and indirect medical costs and impact public health in this setting. It should be noted that most of the participants who were not enrolled were either not captured during surveillance or did not consent to participate in the study. Second, only 53 of 95 RV-positive stool samples were available for strain identification which limited the possibility of describing the circulating strains. Nevertheless, by using a reference laboratory with validated techniques and experience for PCR confirmation, it was possible to provide accurate estimates for the identified strains. Finally, firm conclusions regarding the seasonality of RV and the variation in circulating RV strains could not been drawn as the surveillance activities were conducted for just 1 year following recommendations from WHO.43 Nevertheless, routine surveillance is warranted as RV circulation might vary from one calendar year to another.

Conclusion

RVGE in children aged less than 5 years continues to be a major public health challenge in the Republic of Ivory Coast. In our study, the disease, which peaked in July and August, mainly affected infants aged 6–11 months. Wild-type G1P[8] and G8P[6] were the most frequently reported RV types. The inclusion of a RV vaccine into local preventative programmes might, therefore, help to reduce the disease burden of RVGE.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Véronique Agbaya-Akran Awo and Mariam Drame for their contribution to the study conduct at the site; Vrushali Sanghrajka for statistical inputs. The authors also thank Dr Lamine Soumahoro (head of Medical Department) and Dr Marie-José Anguibi-Pokou (both employed by GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) group of companies) for their involvement in monitoring of the study sites, ensuring the supply of study material and conducting trainings on Good Clinical practices. The authors acknowledge the contributions of Dominique Luyts and Karin Hallez for providing logistical support as clinical operation managers and Rodrigo DeAntonio for intellectual inputs and review of the manuscript (all employed by GSK group of companies); Dr Ekaza Euloge from Pasteur Institute of Ivory Coast for his assistance in molecular testing in Abidjan; Dr Berah and Dr Niamen for sample collection; DDL Diagnostic Laboratory (the Netherlands) for performing reverse transcriptase (RT)-PCR and nested PCR to determine rotavirus G and P types. The authors also thank Harshith Bhat (employed by GSK group of companies) for medical writing, Abdelilah Ibrahimi (XPE Pharma and Science for GSK group of companies) and Valentine Wascotte for Publication coordination (all employed by GSK group of companies) and Julia Donnelly for copy-editing (freelance on behalf of GSK group of companies).

Footnotes

Contributors: CA-K was the principal investigator and contributed to the conception, design, analysis and interpretation of the study. VAK and JJYA coordinated the study together with CA-K and contributed to the interpretation of the results. All authors participated in the development of this manuscript.

Funding: GSK Biologicals SA was the funding source and was involved in all stages of the study conduct and analysis. GSK Biologicals SA also took in charge all costs associated with the development and the publishing of the present manuscript.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: National Ethics Committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Researchers can request access to anonymised patient-level data from GSK clinical studies to conduct further research through the GSK website at the following URL address: https://clinicalstudydata.gsk.com

References

- 1.Parashar UD, Hummelman EG, Bresee JS, et al. Global Illness and deaths caused by rotavirus disease in children. Emerg Infect Dis 2003;9:565–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tate JE, Burton AH, Boschi-Pinto C, et al. WHO-coordinated Global Rotavirus Surveillance Network. 2008 estimate of worldwide rotavirus-associated mortality in children younger than 5 years before the introduction of universal rotavirus vaccination programmes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 2012;12:136–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parashar UD, Burton A, Lanata C, et al. Global mortality associated with rotavirus disease among children in 2004. J Infect Dis 2009;200:S9–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sanchez-Padilla E, Grais RF, Guerin PJ, et al. Burden of disease and circulating serotypes of rotavirus infection in sub-Saharan Africa: systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 2009;9:567–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parashar UD, Bresee JS, Gentsch JR, et al. Rotavirus. Emerg Infect Dis 1998;4:561–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Glass RI, Kilgore PE, Holman RC, et al. The epidemiology of rotavirus diarrhea in the United States: surveillance and estimates of disease burden. J Infect Dis 1996;174:S5–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gurwith M, Wenman W, Gurwith D, et al. Diarrhea among infants and young children in Canada: a longitudinal study in three northern communities. J Infect Dis 1983;147:685–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rodriguez WJ, Kim HW, Brandt CD, et al. Longitudinal study of rotavirus infection and gastroenteritis in families served by a pediatric medical practice: clinical and epidemiologic observations. Pediatr Infect Dis J 1987;6:170–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cunliffe NA, Kilgore PE, Bresee JS, et al. Epidemiology of rotavirus diarrhea in Africa: a review to assess the need for rotavirus immunization. Bull World Health Organ 1998;76:525–37 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Naficy AB, Abu-Elyazeed R, Holmes JL, et al. Epidemiology of rotavirus diarrhea in Egyptian children and implications for disease control. Am J Epidemiol 1999;150:770–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cunliffe NA, Nakagomi O. A critical time for rotavirus vaccines: a review. Expert Rev Vaccines 2005;4:521–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Glass RI, Bresse JS, Turcios R, et al. Rotavirus vaccines: targeting the developing world. J Infect Dis 2005;192:S160–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Steele AD, Ivanoff B. Rotavirus strains circulating in Africa during 1996–1999: emergence of G9 strains and P[6] strains. Vaccine 2003;21:361–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang J, Wang T, Wang Y, et al. Emergence of human rotavirus group A genotype G9 strains, Wuhan, China. Emerg Infect Dis 2007;13:1587–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Atkinson W, Hamborsky J, McIntyre L, et al. Epidemiology and prevention of vaccine-preventable diseases. Washington, DC: Public Health Foundation, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cowpli-Bony M, Loukou YG, Teby A, et al. Technique immunoenzymatique epidemiologie des diarrhees aigues a rotavirus chez 115 enfants diarrheiques atteints de malnutrition a Abidjan. Rev Med Côte d'Ivoire 1987;79:21–5 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lougou YG, Selly E. Sous-groupes de rotavirus humains en Côte d'Ivoire determines par immunoenzymologie. Rev Med Côte d'Ivoire 1987;81:4–9 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Akoua-Koffi C, Faye-Kette H, Kouakou K, et al. Interet de l'utilisation d'un test au latex (Rotalex) pour le depistage de rotavirus dans les selles diarrheiques a Abidjan. Med Afr Noire 1993;40:599–602 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Akran VA, Akoua-Koffi C, Hette K, et al. Electrophoretypes of rotavirus in children 15 years of age in Abidjan, Côte d'Ivoire in 1997. Afr J Health Sci 2001;8:33–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Niangue-Beugre NN, Couitchere L, Oulai SM, et al. Aspect epidemiologiques, cliniques et etiologiques des diarrhees aigues des enfants ages de 1 mois a 5 ans recus dans le service de pediatrie du CHU de Treichville (Côte d'Ivoire). Arch Pediatr 2006;13:395–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Akoua-Koffi C, Akran V, Peenze I, et al. Epidemiological and virological aspects rotavirus diarrhea in Abidjan, Côte d'Ivoire (1997–2000). Bull Soc Pathol Exot 2007;100:246–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ruuska T, Vesikari T. Rotavirus disease in Finnish children: use of numerical scores for clinical severity of diarrheal episodes. Scand J Infect Dis 1990;22:259–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Doorn LJ, Kleter B, Hoefnagel E, et al. Detection and genotyping of human rotavirus VP4 and VP7 genes by reverse transcriptase PCR and reverse hybridization. J Clin Microbiol 2009;47:2704–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Junaid SA, Umeh C, Olabode AO, et al. Incidence of rotavirus infection in children with gastroenteritis attending Jos university teaching hospital, Nigeria. Virol J 2011;8:233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khoury H, Ogilvie I, El Khoury AC, et al. Burden of rotavirus gastroenteritis in the Middle Eastern and North African pediatric population. BMC Infect Dis 2011;11:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abugalia M, Cuevas L, Kirby A, et al. Clinical features and molecular epidemiology of rotavirus and norovirus infections in Libyan children. J Med Virol 2011;83:1849–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ochoa TJ, Salazar-Lindo E, Cleary TG. Management of children with infection-associated persistent diarrhea. Semin Pediatr Infect Dis 2004;15:229–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Uysal G, Sökmen A, Vidinlisan S. Clinical risk factors for fatal diarrhea in hospitalized children. Indian J Pediatr 2000;67:329–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Armah GE, Steele AD, Esona MD, et al. Diversity of rotavirus strains circulating in West Africa from 1996 to 2000. J Infect Dis 2010;202(Suppl):S64–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Todd S, Page NA, Steele DA, et al. Rotavirus strain types circulating in Africa: review of studies published during 1997–2006. J Infect Dis 2010;202:S34–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.World Health Organization Rotavirus surveillance in the African Region. Updates of Rotavirus surveillance in the African Region. http://www.afro.who.int/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=2486:rotavirus-surveillance-in-the-african-region&catid=1980&Itemid=2737 (accessed 26 Jul 2013).

- 32.Dennehy PH. Transmission of rotavirus and other enteric pathogens in the home. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2000;19:S103–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parashar UD, Gibson CJ, Bresse JS, et al. Rotavirus and severe childhood diarrhea. Emerg Infect Dis 2006;12:304–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Paulke-Korienk M, Rendi-Wagner P, Kundi M, et al. Universal mass vaccination against rotavirus gastroenteritis: impact on hospitalization rates in Austrian children. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2010; 29:319–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Richardson V, Hernandez-Pichardo J, Quintanar-Solares M, et al. Reduction in childhood diarrhea deaths after rotavirus vaccine introduction in Mexico. N Engl J Med 2010;362:299–305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yen C, Tate JE, Patel MM, et al. Rotavirus vaccines: update on global impact and future priorities. Hum Vaccin 2011;7:1282–90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Centers for Disease Control Rotavirus surveillance—worldwide, 2001–2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2008;57:1255–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ruiz-Palacios GM, Pérez-Schael I, Velázquez FR, et al. Safety and efficacy of an attenuated vaccine against severe rotavirus gastroenteritis. N Engl J Med 2006;354:11–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Linhares AC, Velázquez FR, Pérez-Schael I, et al. Efficacy and safety of an oral live attenuated human rotavirus vaccine against rotavirus gastroenteritis during the first 2 years of life in Latin American infants: randomized, double-blind controlled study. Lancet 2008;371:1181–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Madhi SA, Cunliffe NA, Steele D, et al. Effect of human rotavirus vaccine on severe diarrhea in African infants. N Engl J Med 2010;362:289–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Armah GE, Sow SO, Breiman RF, et al. Efficacy of pentavalent rotavirus vaccine against severe rotavirus gastroenteritis in infants in developing countries in sub-Saharan Africa: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2010;376:606–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Meeting of the Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on immunization, October 2009—conclusions and recommendations. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 2009;84:517–32 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.World Health Organization Generic protocols for (i) hospital-based surveillance to estimate the burden of rotavirus gastroenteritis in children and (ii) a community-based survey on utilization of health care services for gastroenteritis in children. Vaccine Assessment and Monitoring team of the Department of Vaccines and Biologicals. 2002, Vol. WHO/V&B/02.15

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.