Abstract

Context:

Total thyroidectomy with central lymph node dissection is recommended in patients with medullary thyroid cancer (MTC). However, the relationship between disease severity and extent of resection on overall survival remains unknown.

Objective:

The aim of the study was to identify the effect of surgery on overall survival in MTC patients.

Methods:

Using data from 2968 patients with MTC diagnosed between 1998 and 2005 from the National Cancer Database, we determined the relationship between the number of cervical lymph node metastases, tumor size, distant metastases, and extent of surgery on overall survival in patients with MTC.

Results:

Older patient age (5.69 [95% CI, 3.34–9.72]), larger tumor size (2.89 [95% CI, 2.14–3.90]), presence of distant metastases (5.68 [95% CI, 4.61–6.99]), and number of positive regional lymph nodes (for ≥16 lymph nodes, 3.40 [95% CI, 2.41–4.79]) were independently associated with decreased survival. Overall survival rate for patients with cervical lymph nodes resected and negative, cervical lymph nodes not resected, and 1–5, 6–10, 11–16, and ≥16 cervical lymph node metastases was 90, 76, 74, 61, 69, and 55%, respectively. There was no difference in survival based on surgical intervention in patients with tumor size ≤ 2 cm without distant metastases. In patients with tumor size > 2.0 cm and no distant metastases, all surgical treatments resulted in a significant improvement in survival compared to no surgery (P < .001). In patients with distant metastases, only total thyroidectomy with regional lymph node resection resulted in a significant improvement in survival (P < .001).

Conclusions:

The number of lymph node metastases should be incorporated into MTC staging. The extent of surgery in patients with MTC should be tailored to tumor size and distant metastases.

Medullary thyroid cancer (MTC) is a rare thyroid cancer and accounts for up to 4% of all thyroid cancers in the United States (1). More than 50% of patients with MTC have cervical lymph node metastases at the time of the diagnosis, and up to 5% have distant metastases (2). Using the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) fifth TNM classification system, 10-year survival rates for stages I, II, III, and IV MTC are 100, 93, 71, and 21%, respectively (3). Based on the 2009 American Thyroid Association (ATA) Guidelines for MTC and the North American Neuroendocrine Tumor Society (NANETS) Consensus Guideline for the diagnosis and management of neuroendocrine tumors, standard treatment for clinical MTC is total thyroidectomy with prophylactic central lymph node dissection in clinically node-negative patients and therapeutic neck dissection in patients with clinically suspicious lymph nodes in the central or lateral neck on physical examination, imaging, or intraoperative assessment (4, 5).

Despite a clearly defined surgical plan, the efficacy of this “one size fits all” surgical approach to MTC remains unclear. The utility of a thorough lymph node dissection in patients with distant metastases is debatable. The most recent ATA guidelines support less aggressive surgery in patients with distant metastases, with the goal of palliation (4). Similarly, because low-risk MTC patients have an excellent prognosis, the benefit of a prophylactic central lymph node dissection in the lowest-risk patients is also unclear. In addition, although there is one small study evaluating the impact of the number of lymph node metastases on outcome, the most recent AJCC staging system does not incorporate the number of lymph node metastases into staging (6, 7). Because most of the previous studies on MTC have a small patient cohort, it was previously difficult to assess treatment benefit and the role of the number of lymph node metastases on outcome (8, 9). Using a large, national, population-based cancer database, we hypothesized that there would be an inverse relationship between the number of lymph node metastases and survival. We also anticipated a survival benefit to high-risk patients, including patients with distant metastases treated with lymph node dissection, and we hypothesized that there would be little or no benefit to more extensive neck dissections in the lowest-risk patients. Our hypotheses are for patients with clinical MTC as opposed to familial disease with prophylactic surgery being considered.

Patients and Methods

Data source and study population

Data from 2968 patients diagnosed with MTC between 1998 and 2005 were gathered from the National Cancer Database (NCDB). Data came from the NCDB Participant User File. The NCDB is a US nationwide oncology data set that captures 70% of all newly diagnosed malignant cancers, including close to 85% of all thyroid cancers, in the United States (10). The NCDB is a joint project of the Commission on Cancer of the American College of Surgeons and the American Cancer Society. Data from thyroid cancer cases were queried, and International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes consistent with MTC were used to identify this study cohort. Data were censored at death or a minimum of 5 years after diagnosis. Median follow-up was 6 years. The University of Michigan Institution Review Board (IRB) reviewed this proposal. The IRB felt approval was not required because the data cannot be tracked to human subjects.

Measures

Included in our analysis were the variables age, sex, ethnicity, insurance, income, education level, rural vs urban continuum, tumor size, regional lymph nodes, distant metastases, and surgical treatment. Because MTC can be part of multiple endocrine neoplasia, patient age was stratified into three biologically relevant groups: age 30 years or younger (because multiple endocrine neoplasia is often associated with MTC diagnosis at a younger age), ages 31 to 64, and age 65 or older. Because there was a small number of races other than black or white, the Asian, American Indian/Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander categories were collapsed into an “other” race category. Ethnicity was divided into non-Hispanic and Hispanic. Persons of Hispanic origin could be any race, and therefore race instead of ethnicity was included in the multivariable analysis. Race/ethnicity was included in this analysis because it has been shown to influence cancer treatment (11). Insurance status was categorized as the following: private/government, Medicare, Medicaid, uninsured, or unknown. By matching the ZIP code of the patient recorded at the time of diagnosis against files derived from year 2000 US Census data, income and education level less than a high school diploma were assigned to each patient. By matching the patient's state and county Federal Information Processing Standard code recorded at the time of diagnosis against files published by the US Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service, the rural-urban continuum variable was created.

Because the AJCC staging for MTC changed in 2003, including the addition of stage IVA, IVB, and IVC disease and T3 tumors being classified as stage III instead of stage II cancer, we used tumor size, number of lymph node metastases, and distant metastases in our analysis instead of stage (12). Tumor size was categorized into tumors less than or equal to 1 cm, 1.1 to 2 cm, 2.1 to 4 cm, more than 4 cm, or unknown. Tumor histology was limited to ICD for Oncology classification codes for MTC. For surgical intervention, we identified patients with total thyroidectomy, lobectomy, or no surgical treatment. Total thyroidectomy refers to patients who underwent total thyroidectomy with either no cervical lymph node dissection or unavailable information about cervical lymph node dissection. Cervical lymph nodes were also assessed based on positive lymph nodes vs negative lymph nodes vs non-resected lymph nodes. Patients with positive cervical lymph nodes were analyzed based on the number of positive cervical lymph nodes: 1 to 5, 6 to 10, 11 to 15, and 16 or more positive nodes. Distant metastases were assessed based on the presence or absence of distant metastases as reported in the database.

Statistical analysis

Our primary outcome was overall survival. Univariate analysis was performed using the Kaplan-Meier method with log-rank statistics to detect differences in overall survival.

Cox proportional hazard regression modeling was used for multivariable analysis. If the 95% confidence interval (CI) of the hazard ratio (HR) did not cross 1.00, then the relationship was considered statistically significant.

Results

Between 1998 and 2005, 2968 patients with MTC were analyzed. As shown in Table 1, most patients were women (58.6%) and were between 31 and 64 years old (65.3%). A total of 815 patients (27.5%) were older than 65 years. The mean age of our patients was 54 ± 16 years. Eighty-six percent were white, 8.3% were black, and only 3.5% fell into the “other” race category. A small minority (5.9%) were Hispanic. In this cohort, 24.6% of patients had Medicare insurance, and 62.8% had private insurance. With respect to treatment, 83% of patients had total thyroidectomy, 10.2% had lobectomy, and 6.8% had no surgery. Among 1952 patients who underwent cervical lymph node dissection, 1141 patients had positive cervical lymph node metastases (58.4%).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Patients Diagnosed With MTC Between 1998 and 2005 (n = 2968)

| Characteristics | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Patient characteristics | |

| Sex | |

| Male | 1230 (41.4) |

| Female | 1738 (58.6) |

| Age, y | |

| < 30 | 214 (7.2) |

| 31–64 | 1939 (65.3) |

| > 65 | 815 (27.5) |

| Race | |

| White | 2560 (86.3) |

| Black | 247 (8.3) |

| Other | 105 (3.5) |

| Unknown | 56 (1.9) |

| Hispanic | |

| Yes | 174 (5.9) |

| No | 2551 (85.9) |

| Unknown | 243 (8.2) |

| Insurance | |

| Private/Government | 1863 (62.8) |

| Medicare | 731 (24.6) |

| Medicaid | 107 (3.6) |

| Uninsured | 93 (3.1) |

| Unknown | 174 (5.9) |

| Income | |

| <$30 000 | 367 (12.4) |

| $30 000–34 999 | 465 (15.6) |

| $35 000–45 999 | 730 (24.6) |

| $46 000+ | 1220 (41.1) |

| Unknown | 186 (6.3) |

| Education level less than high school diploma, % | |

| 29+ | 427 (14.4) |

| 20–28.9 | 627 (21.1) |

| 14–19.9 | 645 (21.7) |

| <14 | 1083 (36.5) |

| Unknown | 186 (6.3) |

| Rural-urban continuum | |

| Metropolitan population | 2302 (77.6) |

| Other | 472 (15.9) |

| Unknown | 194 (6.5) |

| Tumor characteristics | |

| Size, cm | |

| < 1 | 571 (19.2) |

| 1.1–2.0 | 717 (24.2) |

| 2.1–4.0 | 1023 (34.5) |

| >4.0 | 527 (17.7) |

| Unknown | 130 (4.4) |

| Distant metastases | |

| Yes | 329 (11.1) |

| No | 2639 (88.9) |

| Treatment | |

| Surgery | |

| Total thyroidectomy | 2465 (83.0) |

| Lobectomy | 302 (10.2) |

| No surgery | 201 (6.8) |

| Regional lymph nodes resected | |

| Yes | 1952 (65.8) |

| No | 963 (32.4) |

| Unknown | 53 (1.8) |

| Regional lymph nodes positive | |

| Yes | 1141 (38.4) |

| No | 806 (27.2) |

| Unknown | 1021 (34.4) |

The unknown category for regional lymph nodes positive includes patients that didn't have lymph nodes resected (n = 963), patients that had lymph nodes resected but the presence of metastases was unknown (n = 5), and patients with resection unknown (n = 53).

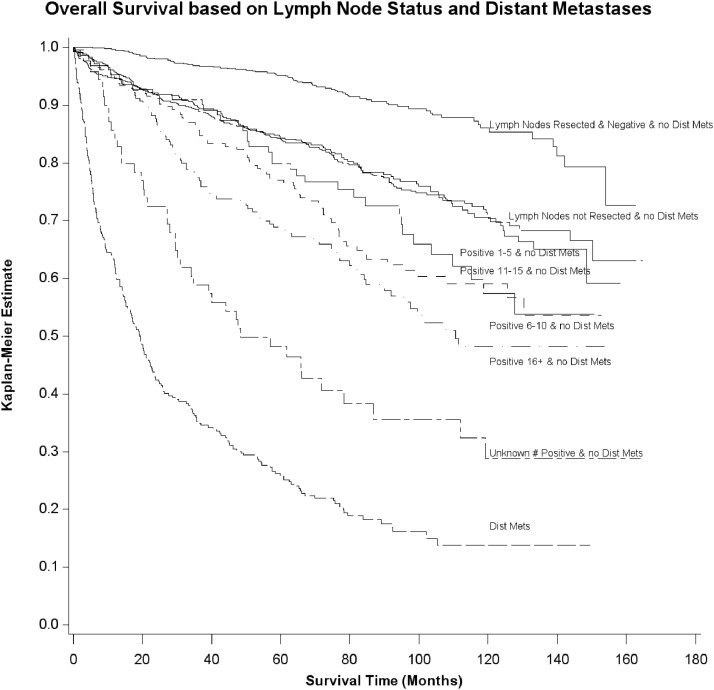

In Figure 1, Kaplan-Meier curves illustrate survival in patients diagnosed between 1998 and 2005 based on the number of cervical lymph node metastases and distant metastases. Ninety-five percent and 86% of patients with no cervical lymph node metastases or distant metastases were alive at 5 and 10 years, respectively. Eighty-four percent and 71% of patients with no cervical lymph node resected and no distant metastases were alive at 5 and 10 years, respectively. Eighty-four percent and 70% with ≤ five metastatic cervical lymph nodes without distant metastases were alive at 5 and 10 years, respectively. Seventy-seven percent and 59% of patients with 6–10 cervical lymph node metastases were alive at 5 and 10 years, respectively. Eighty percent and 57% of patients with 11–15 cervical lymph node metastases were alive at 5 and 10 years, respectively. Sixty-eight percent and 48% of patients with 16 or more cervical lymph node metastases were alive at 5- and 10-year follow-up, respectively. Twenty-six percent and 14% of patients with distant metastases were alive at 5- and 10-year follow-up, respectively.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier estimate showing overall survival of patients with MTC based on the number of cervical lymph node metastases and distant metastases. Dist Mets, distant metastases.

As demonstrated in Table 2, overall survival for patients with no cervical lymph node metastases, cervical lymph nodes not resected, and 1–5, 6–10, 11–15, and ≥16 cervical lymph node metastases was 90, 76, 74, 61, 69, and 55% respectively. Overall survival for patients with distant metastases was 22%. Patients older than 65 (adjusted HR [AHR], 5.69 [95% CI, 3.34–9.72]), tumor size above 4 cm (AHR, 2.89 [95% CI, 2.14–3.90]), number of positive cervical lymph nodes (≥16 lymph nodes, AHR, 3.40 [95% CI, 2.41–4.79]), and presence of distant metastases (AHR, 5.68 [95% CI, 4.61–6.99]) were associated with decreased overall survival.

Table 2.

Cox Proportional Hazard Regression for Association of Patient and Tumor Characteristics with Overall Survival in Patients with MTC (n = 2467)

| Characteristics | n (%) | Deceased n (%) | Unadjusted HR (95% CI) | Adjusted HR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient characteristics | ||||

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 1007 (40.8) | 320 (31.8) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Female | 1460 (59.2) | 278 (19.0) | 0.55 (0.47, 0.64) | 0.81 (0.68, 0.97) |

| Age, y | ||||

| < 30 | 173 (7.0) | 18 (10.4) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 31–64 | 1607 (65.1) | 265 (16.5) | 1.53 (0.95, 2.47) | 1.59 (0.98, 2.58) |

| > 65 | 687 (27.9) | 315 (45.9) | 5.32 (3.31, 8.55) | 5.69 (3.34, 9.72) |

| Race | ||||

| White | 2148 (87.1) | 541 (25.2) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Black | 194 (7.9) | 43 (22.2) | 0.90 (0.66, 1.22) | 1.07 (0.77, 1.48) |

| Other | 125 (5.0) | 14 (11.2) | 0.45 (0.26, 0.76) | 0.69 (0.41, 1.19) |

| Insurance | ||||

| Private/Government | 1644 (66.6) | 271 (16.5) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Medicare | 647 (26.2) | 280 (43.3) | 3.17 (2.68, 3.75) | 1.03 (0.79, 1.36) |

| Medicaid | 96 (4.0) | 23 (24.0) | 1.58 (1.03, 2.42) | 1.57 (1.01, 2.44) |

| Uninsured | 80 (3.2) | 24 (30.0) | 2.38 (1.57, 3.61) | 1.58 (1.02, 2.44) |

| Education level less than high school diploma, % | ||||

| 29 + | 386 (15.7) | 93 (24.1) | 1.28 (1.00, 1.63) | 0.98 (0.75, 1.27) |

| 20–28.9 | 550 (22.3) | 145 (26.4) | 1.34 (1.08, 1.65) | 1.13 (0.91, 1.42) |

| 14–19.9 | 576 (23.3) | 158 (27.4) | 1.37 (1.11, 1.69) | 1.23 (0.99, 1.52) |

| <14 | 955 38.7) | 202 (21.2) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Rural-urban continuum | ||||

| Metropolitan population | 2053 (83.2) | 480 (23.4) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Other | 414 (16.8) | 118 (28.5) | 1.06 (1.02, 1.10) | 1.04 (0.99, 1.08) |

| Tumor characteristics | ||||

| Size, cm | ||||

| <1 | 492 (19.9) | 58 (11.8) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 1.1–2.0 | 621 (25.2) | 93 (15.0) | 1.17 (0.84, 1.62) | 1.21 (0.87, 1.68) |

| 2.1–4.0 | 899 (36.5) | 234 (26.0) | 2.17 (1.63, 2.89) | 1.88 (1.40, 2.52) |

| >4.0 | 455 (18.4) | 213 (46.8) | 4.68 (3.50, 6.26) | 2.89 (2.14, 3.90) |

| Regional lymph nodes | ||||

| Negative | 689 (27.9) | 66 (9.6) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Not resected | 823 (33.4) | 200 (24.3) | 2.82 (2.14, 3.73) | 2.07 (1.56, 2.75) |

| Positive | ||||

| 1–5 | 425 (17.2) | 110 (25.9) | 2.71 (2.00, 3.68) | 1.90 (1.40, 2.59) |

| 6–10 | 189 (7.7) | 73 (38.6) | 4.45 (3.19, 6.21) | 2.77 (1.96, 3.93) |

| 11–15 | 111 (4.5) | 35 (31.5) | 3.37 (2.24, 5.08) | 2.24 (1.46, 3.43) |

| >16 | 175 (7.1) | 79 (45.1) | 5.58 (4.03, 7.74) | 3.40 (2.41, 4.79) |

| No. unknown | 55 (2.2) | 35 (63.6) | 10.06 (6.67, 15.16) | 5.35 (3.50, 8.16) |

| Distant metastases | ||||

| Yes | 180 (7.3) | 140 (77.8) | 8.71 (7.18, 10.56) | 5.68 (4.61, 6.99) |

| No | 2287 (92.7) | 458 (20.0) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

In Table 3, we evaluated the overall survival based on three risk groups: tumor size ≤ 2 cm and no distant metastases; tumor size > 2 cm and no distant metastases; and any tumor size and distant metastases. For this treatment analysis we excluded 415 patients with no specific data on any treatment. The overall survival rate was 88.8% in patients with tumor size ≤ 2.0 cm and no distant metastases. The overall survival rate decreased to 72.4% in patients with tumor size larger than 2.0 cm without distant metastases. When distant metastases were present, the overall survival was only 21%, regardless of tumor size. In patients with tumor size > 2.0 cm and no distant metastases, all surgical treatments resulted in a significant improvement in survival compared to no surgery (P < .001); and for patients with distant metastases, only total thyroidectomy with regional lymph node resection resulted in a significant improvement in survival (P < .0001), with 30% surviving vs 15% who underwent no surgical intervention. We repeated the analysis controlling for age and gender, and the findings didn't change. In addition, we looked specifically at the proportion of each subgroup that had lymph node resections and found that of those who underwent lymph node resections, 43% of patients with tumor size ≤ 2.0 cm with no distant metastases had cervical lymph node metastases compared to 65% of patients with tumors larger than 2 cm without distant metastases. With the presence of distant metastases, the number of patients with cervical lymph node metastases among those who had lymph node resections rose to 95%.

Table 3.

Treatment Effect on Overall Survival by Risk Group (n = 2968)

| n (%) | Deceased n (%) | Unadjusted HR (95% CI) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor size <2 cm and no distant metastases | ||||

| No surgery | 17 (1.4) | 1 (5.9) | 1.00 | |

| Lobectomy | 139 (11.2) | 18 (13.0) | 2.35 (0.31, 17.64) | .4050 |

| Total thyroidectomy | 337 (27.0) | 39 (11.6) | 2.11 (0.29, 15.36) | .4610 |

| Total thyroidectomy + regional lymph nodes resected | 753 (60.4) | 84 (11.2) | 2.00 (0.28, 14.39) | .4900 |

| Tumor size >2.0 cm and no distant metastases | ||||

| No surgery | 36 (2.6) | 22 (61.1) | 1.00 | |

| Lobectomy | 138 (9.9) | 42 (30.4) | 0.29 (0.18, 0.49) | <.0001 |

| Total thyroidectomy | 307 (22.0) | 67 (21.8) | 0.21 (0.13, 0.33) | <.0001 |

| Total thyroidectomy + regional lymph nodes resected | 912 (65.5) | 252 (27.6) | 0.26 (0.17, 0.40) | <.0001 |

| Any tumor size and distant metastases | ||||

| No surgery | 148 (45.0) | 126 (85.1) | 1.00 | |

| Lobectomy | 25 (7.6) | 19 (76.0) | 0.63 (0.39, 1.02) | .0590 |

| Total thyroidectomy | 29 (8.8) | 26 (89.7) | 0.88 (0.58, 1.35) | .5610 |

| Total thyroidectomy + regional lymph nodes resected | 127 (38.6) | 89 (70.1) | 0.50 (0.38, 0.66) | <.0001 |

Discussion

This study is among the few studies analyzing the overall survival of patients with MTC based on the tumor size and number of cervical lymph node metastases and distant metastases. There is an inverse relationship between the number of cervical lymph node metastases and survival. In this large sample of patients with MTC treated in the United States, there was no significant difference in overall survival based on surgical intervention in patients with tumor size < 2 cm and no distant metastases. The outcome of these patients was excellent regardless of intervention. However, more extensive surgical resection resulted in a significant improvement in survival in patients with distant metastases.

The 2009 ATA guidelines for MTC recommend total thyroidectomy with prophylactic central lymph node dissection in patients with clinically node-negative MTC. Therapeutic lateral neck dissection is recommended if there is evidence of lymph node involvement preoperatively on physical examination or imaging studies or based on intraoperative morphological appearance (4, 5). In addition, less aggressive surgery can be considered in patients with distant metastases with the goal of obtaining adequate locoregional control rather than complete excision of cervical disease (4). However, the true relationship between disease severity and extent of resection on overall survival remains unknown. Although the recent ATA and NANETS guidelines support thyroidectomy with central lymph node dissection, our data suggest that if overall survival is the primary end point, then cervical lymph node dissection can be tailored to tumor size and the presence or absence of distant metastases. Although the reasons are not clear, it is possible that more extensive neck dissection improves survival in patients with distant metastases because, although it is an aggressive cancer compared to papillary thyroid cancer, MTC is still relatively slow growing. Death secondary to the distant metastases may take years, and thus local tumor debulking may prevent earlier death secondary to locally invasive disease. In contrast, our lowest-risk cohort (tumor size ≤ 2 cm and no distant metastases) had an excellent overall survival regardless of intervention. However, we do not know whether lymph node dissections have additional benefits in this lower-risk cohort, such as decreased cancer recurrence. In addition, although not specific to tumor size ≤ 2 cm, lymph node resection in general helped with prognostication because patients with no lymph node metastases did better than those with no lymph nodes resected; and the number of lymph node metastases correlated with survival. Further studies are still needed to determine whether prophylactic lymph node dissection is beneficial when tumor size is ≤ 2 cm.

The AJCC/Union International Contre le Cancer (UICC) TNM classification system categorizes all cancers with distant metastases to the highest tumor stage (7, 12, 13). For N staging, the AJCC/UICC classification uses incremental N categories of lymph node metastases for some cancers such as colorectal cancer and gastric cancer, but not for MTC (7, 12, 13). The N staging for MTC is categorized by locations of cervical node metastases in the central neck (N1a) or outside of central neck (N1b). Machens and Dralle (6) studied 715 patients with MTC and demonstrated that the number of cervical lymph node metastases would influence the prognosis of patients with MTC. In this study, they divided patients with lymph node metastases into three groups: low risk (n = 1–10), intermediate risk (n = 11–20), and high risk (n > 20). They suggested that the quantity of lymph node metastases is an important prognostic classifier that should be incorporated into MTC staging systems for better risk stratification. Our cohort is four times larger than Machens and Dralle's and is specific to the United States. We demonstrate similar findings in that the number of cervical lymph node metastases clearly influences the overall survival.

Previous studies suggest that approximately 50% of patients with MTC have lymph node metastases (2). However, Kazaure et al (14) reviewed data from 310 patients with MTC included in the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) registry and found that tumor size ≤ 5 mm is associated with only 23% of patients having lymph node metastases. Our data also suggest a relationship between tumor size and likelihood of lymph node metastases because we found that of the patients that underwent lymph node resection, 43% of those with tumor size smaller than 2 cm had cervical lymph node metastases, and this rose to 65% with tumor size larger than 2 cm and to 95% in patients with distant metastases.

Roman et al (15) previously found that stage and patient age were the strongest predictors of survival in patients with MTC. Gilliland et al (16) also found that age was a strong predictor of survival in patients with MTC. Our study demonstrates that age, distant metastases, and number of cervical lymph node metastases are important and correlate with overall survival.

The strengths of this study include a large sample size of patients (n = 2968), an exhaustive set of patient variables, and details on the number of lymph node metastases and whether or not lymph node resection was performed. In addition, this study is comprehensive and includes data from a large number of hospitals in the United States. However, a study using a large database such as the National Cancer Database has limitations. Specific to MTC, calcitonin and carcinoembryonic antigen levels are not recorded. Therefore, doubling time of calcitonin and carcinoembryonic antigen, which is known to be a predictor of overall survival, could not be calculated (17). An additional limitation is the fact that details on preoperative ultrasound and whether or not lymph node dissections were prophylactic vs therapeutic are unknown. Similar to most other studies using data from cancer registries, we did not have access to recurrence data, and the specific site of distant metastases was not included in the analysis. This analysis is also a retrospective study and, unlike randomized controlled trials, does not allow for stratification according to factors that are associated with outcome. However, we did control for all known patient characteristics in our large cohort. Related to the fact that this is not a randomized controlled trial, there is also a risk for treatment selection bias. For example, it is possible that baseline patient health and preoperative ultrasound findings influence the likelihood of lymph node resection. Although the use of overall survival as the primary outcome could be seen as a limitation, previous studies have shown that disease-specific survival also has limitations due to death certificate errors. Thus, overall survival may be better (18, 19).

By evaluating this large cohort of MTC patients, our study suggests a need for tailored treatment. Patients with a tumor size of 2 cm or smaller without known cervical lymph node metastases or distant metastases may do well with total thyroidectomy only and no central lymph node dissection. Although survival does not appear to be influenced by more extensive resection in this low-risk cohort, further studies are needed to determine whether or not there are other benefits. In contrast, although the ATA guidelines support more conservative surgery in MTC patients with distant metastases, in our cohort, patients with distant metastases have a clear survival benefit if they receive more extensive surgery. In addition, the number of lymph node metastases plays a clear prognostic role and should be incorporated into staging for MTC.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by a National Institutes of Health K award (K07-CA-154595-02; to M.R.H.).

Brittany Gay assisted with manuscript preparation. The data used in this study are derived from a deidentified NCDB file. The American College of Surgeons and the Commission on Cancer have not verified and are not responsible for either the analytic or statistical methodology employed or the conclusions drawn from these data by the investigator.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- AHR

- adjusted HR

- CI

- confidence interval

- HR

- hazard ratio

- MTC

- medullary thyroid cancer.

References

- 1. Hundahl SA, Fleming ID, Fremgen AM, Menck HR. A National Cancer Data Base report on 53,856 cases of thyroid carcinoma treated in the U.S., 1985–1995. Cancer. 1998;83:2638–2648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Saad MF, Ordonez NG, Rashid RK, et al. Medullary carcinoma of the thyroid. A study of the clinical features and prognostic factors in 161 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 1984;63:319–342 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Modigliani E, Cohen R, Campos JM, et al. Prognostic factors for survival and for biochemical cure in medullary thyroid carcinoma: results in 899 patients. The GETC Study Group. Groupe d'étude des tumeurs à calcitonine. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 1998;48:265–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kloos RT, Eng C, Evans DB, et al. Medullary thyroid cancer: management guidelines of the American Thyroid Association. Thyroid. 2009;19(6):565–612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chen H, Sippel RS, O'Dorisio MS, Vinik AI, Lloyd RV, Pacak K. The North American Neuroendocrine Tumor Society consensus guideline for the diagnosis and management of neuroendocrine tumors: pheochromocytoma, paraganglioma, and medullary thyroid cancer. Pancreas. 2010;39:775–783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Machens A, Dralle H. Prognostic impact of N staging in 715 medullary thyroid cancer patients: proposal for a revised staging system. Ann Surg. 2013;257:323–329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, et al. American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Cancer Staging Manual. 7th ed New York, NY: Springer; 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kebebew E, Ituarte PH, Siperstein AE, Duh QY, Clark OH. Medullary thyroid carcinoma: clinical characteristics, treatment, prognostic factors, and a comparison of staging systems. Cancer. 2000;88:1139–1148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Moley JF, DeBenedetti MK. Patterns of nodal metastases in palpable medullary thyroid carcinoma: recommendations for extent of node dissection. Ann Surg. 1999;229:880–887; discussion 887–888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bilimoria KY, Stewart AK, Winchester DP, Ko CY. The National Cancer Data Base: a powerful initiative to improve cancer care in the United States. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:683–690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR. Unequal treatment: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sobin LH, Gospodarowicz MK, Wittekind C. TNM Classification of Malignant Tumors. 7th ed International Union Against Cancer Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell; 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 13. American Joint Committee on Cancer Comparison guide: Cancer Staging Manual, Fifth versus Sixth Edition. www.cancerstaging.org Accessed June 2013

- 14. Kazaure HS, Roman SA, Sosa JA. Medullary thyroid microcarcinoma: a population-level analysis of 310 patients. Cancer. 2012;118:620–627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Roman S, Lin R, Sosa JA. Prognosis of medullary thyroid carcinoma: demographic, clinical, and pathologic predictors of survival in 1252 cases. Cancer. 2006;107:2134–2142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gilliland FD, Hunt WC, Morris DM, Key CR. Prognostic factors for thyroid carcinoma. A population-based study of 15,698 cases from the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) program 1973–1991. Cancer. 1997;79:564–573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Barbet J, Campion L, Kraeber-Bodéré F, Chatal JF. Prognostic impact of serum calcitonin and carcinoembryonic antigen doubling-times in patients with medullary thyroid carcinoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:6077–6084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hoel DG, Ron E, Carter R, Mabuchi K. Influence of death certificate errors on cancer mortality trends. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:1063–1068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Feuer EJ, Merrill RM, Hankey BF. Cancer surveillance series: interpreting trends in prostate cancer–part II: cause of death misclassification and the recent rise and fall in prostate cancer mortality. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:1025–1032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]