Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Asthma is a common chronic condition. Work-related asthma (WRA) has a large socioeconomic impact and is increasing in prevalence but remains under-recognized. Although international guidelines recommend patient education, no widely available educational tool exists.

OBJECTIVE:

To develop a WRA educational website for adults with asthma.

METHODS:

An evidence-based database for website content was developed, which applied evidence-based website design principles to create a website prototype. This was subsequently tested and serially revised according to patient feedback in three moderated phases (one focus group and two interview phases), followed by face validation by asthma educators.

RESULTS:

Patients (n=10) were 20 to 28 years of age; seven (70%) were female, three (30%) were in university, two (20%) were in college and five (50%) were currently employed. Key format preferences included: well-spaced, bulleted text; movies (as opposed to animations); photos (as opposed to cartoons); an explicit listing of website aims on the home page; and an exploding tab structure. Participants disliked integrated games and knowledge quizzes. Desired informational content included a list of triggers, prevention/control methods, currently available tools and resources, a self-test for WRA, real-life scenario presentations, compensation information, information for colleagues on how to react during an asthma attack and a WRA discussion forum.

CONCLUSIONS:

The website met the perceived needs of young asthmatic patients. This resource could be disseminated widely and should be tested for its effects on patient behaviour, including job choice, workplace irritant/allergen avoidance and/or protective equipment, asthma medication use and physician prompting for management of WRA symptoms.

Keywords: Asthma, Education, e-Health, Occupational asthma, Work-exacerbated asthma, Work-related asthma

Abstract

HISTORIQUE :

L’asthme est une maladie chronique courante. L’asthme en milieu de travail (AMT) a d’importantes conséquences socioéconomiques et présente une prévalence crois-sante, mais il demeure sous-diagnostiqué. Même si on recommande l’éducation du patient dans les lignes directrices internationales, aucun outil éducatif n’est largement disponible.

OBJECTIF :

Créer un site Web sur l’AMT pour les adultes asthmatiques.

MÉTHODOLOGIE :

Les chercheurs ont préparé une base de données fondée sur des données probantes pour déterminer les principes de conception du site Web afin d’en créer un prototype. Celui-ci a ensuite été mis à l’essai et révisé de manière sérielle selon les commentaires des patients, en trois phases modérées (une phase de groupe de travail et deux phases d’entrevues), puis des éducateurs sur l’asthme en ont corroboré la validité apparente.

RÉSULTATS :

Les patients (n=10) avaient de 20 à 28 ans. Sept (70 %) étaient des femmes, trois (30 %) allaient à l’université, deux (20 %) étaient au collège et cinq (50 %) avaient un emploi. Les grandes structures favorisées étaient un texte bien espacé sous forme de puces, des films (de préférence à des animations), des photos (plutôt que des bandes dessinées), une liste explicite des objectifs du site Web sur la page d’accueil et une structure éclatée à onglets. Les participants n’aimaient pas les jeux intégrés et les questionnaires sur les connaissances. Le contenu informatif souhaité incluait une liste d’éléments déclencheurs, des méthodes de prévention et de contrôle, les outils et ressources déjà disponibles, un autotest d’AMT, des présentations de scénarios en situation réelle, de l’information sur la rémunération, de l’information pour les collègues afin qu’ils sachent comment réagir pendant une crise d’asthme et un forum de discussion sur l’AMT.

CONCLUSIONS :

Le site Web répondait aux besoins perçus des jeunes patients asthmatiques. Il pourrait être largement diffusé et devrait être mis à l’essai pour en évaluer les effets sur le comportement des patients, y compris le choix d’emploi, l’évitement des irritants ou des allergènes ou le port d’équipement protecteur en milieu de travail, l’utilisation des médicaments antiasthmatiques et les incitations des médecins à prendre en charge les symptômes d’AMT.

Asthma is a common chronic condition, affecting 9% to 12% of young adults (18 to 25 years of age) in North America (1). Work-related asthma (WRA) consists of either work-exacerbated asthma (WEA) or occupational asthma (OA). WEA occurs when workplace exposures cause exacerbation of pre-existing asthma, which occurs in up to 25% of workers with asthma (2). OA occurs when asthma develops newly as a result of a workplace exposure, and is less common than WEA (3). The socioeconomic impact of WRA is large, has detrimental effects on quality of life, occupational success and economic viability (4), in addition to loss of work days and income (5). The American Thoracic Society estimates that 15% of asthma in adults is attributable to occupational factors (6) and worldwide prevalence is increasing (7,8).

The prevalence of asthma in the preworking age population (10 to 14 years of age) is high, suggesting that adolescents entering the work-force may be particularly at risk for WEA (9). It has been estimated that 1.4 million WRA cases could be prevented annually through education, precautionary measures and medication (10). However, suboptimal exposure and trigger control, as well as medication nonadherence, are well described among adolescents with asthma, and these patients are at greater risk of denying their symptoms and self-medicating (11). Among patients with asthma between 16 and 22 years of age, 65% did not consider asthma to be a factor in career planning and only 54% believed that it was important to wear protective equipment in the workplace when indicated (12). Additionally, 44% could not identify occupations that would aggravate asthma and a majority did not discuss their occupation with their physicians (12).

A consensus statement from the American College of Chest Physicians and a European Task Force statement on WRA has recommended improving worker education to address these gaps (13,14). However, no widely available educational tool exists for this purpose. Accordingly, we aimed to develop a web-based program to provide education on WRA to young adults with asthma who were about to enter or had recently entered the workforce. A web-based educational platform was chosen for its free access, scalability and accessibility. The present article describes the methods and outcome of the development and validation process for this website.

METHODS

The research protocol was approved by the St Michael’s Hospital and University of Toronto Research Ethics Boards (Toronto, Ontario)

Participant recruitment

Patients 18 to 25 years of age were recruited from a previously established cohort of subjects with a self-reported physician diagnosis of asthma (12), and through flyers posted in trade schools, youth employment offices, asthma clinics and primary care physician offices.

Content development

Based on existing literature regarding knowledge gaps (11,12), the following key goals for the tool were defined: defining WRA (including WEA and OA); detailing potential workplace triggers (according to trigger and work type); describing preventive measures (eg, protective equipment, trigger avoidance, controller medications and appropriate health care professional consultation); and providing access to key resources. Content experts (SMT, GML, MR) developed a database of information to be included based on published literature, and industry- and government-sponsored information. Where relevant to WRA, these experts included core asthma educational information recommended in any asthma education program according to best evidence (15). Concurrently, they developed a questionnaire to test the knowledge of WRA concepts.

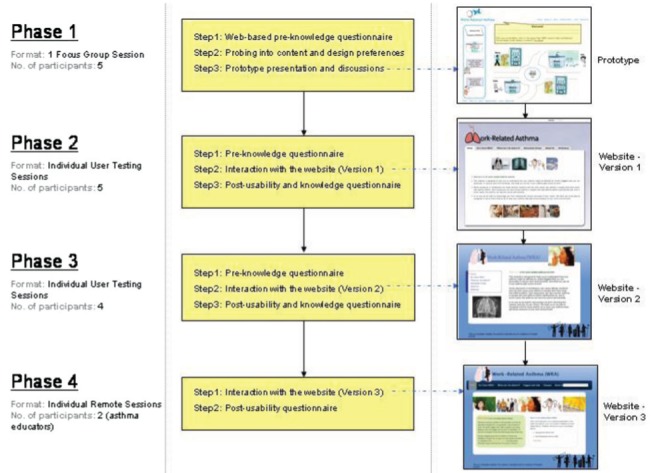

Website prototyping

Human factors engineering experts (SGK, MC) performed a literature search exploring favourable usability features of health education websites, particularly asthma education websites, and any websites targeting young adults and adolescents. Evidence-based criteria were used to evaluate the quality of these websites and to establish a set of target features to guide development (Table 1). User-centred design principles (16,17) were used to design a basic website prototype, including the graphical user interface and organization of content within web pages. User-centred interaction design involves four basic activities: identifying user needs; developing design ideas meeting user needs; building prototypes; and testing the prototypes with end users (16). These activities are serially repeated, with resulting iterative changes to the prototype until designers and end-users are satisfied. By integrating stakeholder perspectives, this iterative ‘improvement’ cycle yields products that are appropriate to the local context and more effectively meet the needs of end users (18,19). The initial prototype was a simple, low-fidelity format to motivate participants to share design recommendations (as opposed to a high-fidelity prototype, which may stifle participant creativity). This prototype was elaborated into the final website through four iterative phases (Figure 1). Sessions were audiotaped, transcribed verbatim and supplemented by moderator field notes. Investigators analyzed and interpreted data between each phase.

TABLE 1.

Website adherence to evidence-based visual design features

| Feature (reference[s]) | Description | How addressed in website design |

|---|---|---|

| Accessibility (20–22) | Readability, accessibility by low-speed Internet |

|

| Ease of use (16,17) | Navigation aids, design consistency across webpages within website, search functionality, uncluttered screen views, condensed text |

|

| Interactivity (17,23,24) | User-interactive website features |

|

| Credibility cues (15,22,25) | Clues to aid readers in gauging website credibility and quality |

|

| Use of multimedia (26) | Inclusion of various multimedia features |

|

| Esthetics (17,20) | Attention to visual appeal of the website |

|

| Catering to distinct learning styles (27) | Creating a web-program that appeals to three kinds of learning: by example; by following step-by-step instructions; and by doing |

|

Feature has not yet been launched;

Waiting final approval from two respiratory organizations. WRA Work-related asthma

Figure 1).

Website development phases

Website development phases

Phase 1:

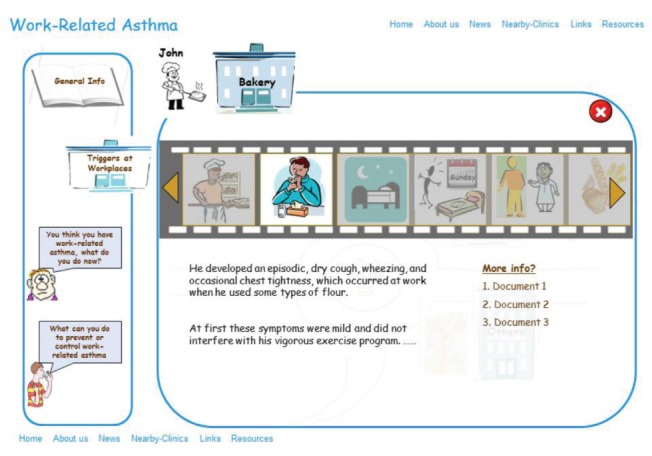

A 2 h moderated focus group was conducted with five participants. Before the session, participants completed a web-based questionnaire ascertaining demographics, asthma history, and knowledge of asthma and WRA. A moderator introduced the study and first posed questions related to informational needs: currently used asthma informational resources; whether participants had sought WRA information on the Internet; and types and priorities for desired WRA information. Subsequent questions probed participant preferences for information presentation and formatting: suggestions for grouping of informational topics (to inform web page organization); preferred presentation formats (text, picture, audio, video, animation); additional features of interest (games, quizzes, forums, discussion groups); and feedback on inclusion of a web-based knowledge test in the website. The prototype website was then presented (Appendix 1: Figure 1) and design comments and suggestions were solicited. Based on these findings, investigators developed a functional website for testing in the next phase.

Phase 2:

The new website (Appendix 1: Figures 2 and 3) was tested in five one-on-one sessions, each 1.5 h in duration. Four of the five participants from phase 1 participated in this phase. Participants first completed the same knowledge questionnaire as in phase 1. Next, after 3 min of website surfing, the interviewer posed open-ended questions about content and format. Participants then completed eight individual information search tasks while ‘thinking aloud’. The moderator graded the ease of task completion on a subjective scale of 0 to 2 (0: not completed; 1: completed with difficulty; and 2: completed easily). Participants completed two exit questionnaires: a usability questionnaire with Likert-scale including the validated System Usability Scale (SUS) (28) and open-ended questions probing perceptions of website content and design; and a knowledge questionnaire asking what new information was learned through the session; and the same knowledge questions as those completed before the session. Investigators analyzed feedback, search task outcomes and exit questionnaires, and implemented corresponding website changes.

Phase 3:

The new version (Appendix 1: Figures 4 and 5) was tested in four one-on-one sessions with new participants. Sessions were structured identically to those in phase 2, with the addition of an additional search task based on findings in phase 2.

Phase 4:

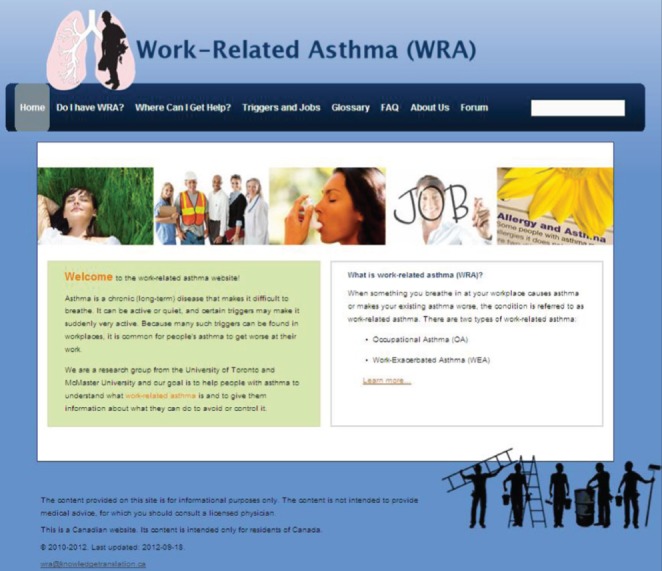

The final version of the website (Figure 2) was presented to a convenience sample of two certified asthma educators for face validation. Educators browsed the website for 1 h from each of their personal computing environments (simulating real-world use) and completed the nine above-described tasks. They then completed an electronic questionnaire probing usability and satisfaction with content and format.

Figure 2).

Final website homepage

RESULTS

Participants

Participants in phases 1 to 3 (n=10) were 20 to 28 years of age; seven (70%) were female, three (30%) were in university, two (20%) were in college and five (50%) were currently employed. Other background characteristics are presented in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Participant characteristics (n=10)

| Characteristic | Participants*, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Asthma care provided by | |

| Family physician | 8 (80) |

| Allergist | 1 (10) |

| Parents/family member | 3 (30) |

| Comorbidities | |

| Allergies | 9 (90) |

| Allergic rhinitis | 4 (40) |

| Eczema | 4 (40) |

| Current smoking | 1 (10) |

| Current medications | |

| Short-acting beta agonist | 7 (70) |

| Inhaled corticosteroid | 5 (50) |

| Long-acting beta agonist | 1 (10) |

| Combined inhaled corticosteroid and long-acting beta agonist | 2 (20) |

| Leukotriene receptor antagonist | 1 (10) |

| Asthma control | |

| Previous ER visit(s) | 6 (60) |

| Previous hospital admission(s) | 4 (40) |

| Nocturnal asthma arousals (past week) | 3 (30) |

| Activity limitation due to asthma (past week) | 6 (60) |

| >3 puffs of rescue bronchodilator (past week) | 3 (30) |

| Agreed with statement: “It is important for people with asthma to use protective measures (eg, masks) in the workplace if asthma triggers are present” | 7 (70) |

| Agreed with statement: “Asthma has been an important factor in determining my choice of a future career” | 2 (20) |

Five subjects participated in phase 1, five in phase 2 (four of the five had also participated in phase 1 and four in phase 3). Thus, a total of 10 individuals participated in phases 1 to 3. ER Emergency room

Website development

Phase 1:

Participants correctly answered a mean (± SD) of 91±4.8% of baseline questions. They identified the following asthma informational resources: physicians, drugstore/doctor’s office pamphlets; television; the ‘WebMD’ website; and friends and family who were health care providers or who had asthma. No participant had previously searched the web for WRA information. Participants indicated a high priority for the following elements: definitions; risks/triggers/allergens; prevention/control methods; how to know that a person has WRA; real-life case scenarios; compensation information for employers; information for colleagues on how to react during an asthma attack; a section for frequently asked questions; information on asthma-related tools; a discussion forum; and currently available resources for WRA. Two participants indicated that personal patient testimonials would be effective. They preferred information to be organized in content groups based on these priority areas, with use of bulleted text for content, and movies or animations for case scenarios. They noted that games, quizzes and any web-based test of knowledge would be undesirable.

Participants appreciated the simplicity and clarity of the prototype and approved its font, colours and layout, tabs on the left (shifting to the left when selected), content in the centre and links on top. They approved of scenarios but preferred real-life pictures/films to cartoons/animations. They preferred the home page to have a basic definition of WRA rather than case scenarios.

Based on these findings, the following changes were made: added three new requested sections – rights of workers, information for work colleagues and a WRA self-test; removed case scenarios from the homepage and included the definition of WRA in the welcome note; produced three video case scenarios; and removed all cartoons.

Phase 2:

Pre- and post-knowledge-questionnaire results are summarized in Table 3. Subjects provided positive feedback about website layout (particularly the tab structure) and informational content. However, all noted that the ‘density’ of text rendered the website ‘boring’ and unattractive.

TABLE 3.

Knowledge, task completion and system usability scale results according to phase

| Phase 2 | Phase 3 | |

|---|---|---|

| Participants, n | 5 | 4 |

| Knowledge scores, % | ||

| Pretest | 89±11 | 91±7 |

| Post-test | 92±9 | 89±5 |

| Task completion scores* | 1.37±0.4 | 1.77±0.32 |

| System usability scores | 74.5±13 | 62±15 |

Data presented as mean ± SD unless otherwise indicated.

Task completion score grading: 0 – not completed, 1 – completed with difficulty, 2 – completed easily

Quantitative results from task completion and SUS scores are provided in Table 3. The most problematic task was one that required participants to look for the specific trigger that should be avoided in a bakery. This was likely due to organization of triggers in the website (divided into OA and WEA tables, each on a separate webpage). Users spent either a long time searching each table for a bakery or were diverted to a separate webpage called ‘Common Triggers’, which did not contain the required information.

The most commonly listed newly learned topics were: that there are two types of WRA; ways to prevent/control/treat WRA; how to make a WRA claim; WRA triggers and jobs; and the effect of isocyanates.

With the help of a commissioned media designer, the following changes were made: removed information deemed ‘unnecessary’; divided long passages into smaller ones on multiple webpages; introduced new pictures and a new colour scheme; reformatted trigger tables by eliminating the ‘Common Triggers’ page and categorizing all triggers as either WEA or OA related; added relevant pictures to each trigger table; emphasized the difference between OA and WEA; and reformatted the logos to increase visual appeal. To determine whether the changes rendered trigger tables easier to navigate, an extra task was added to step 2 of the next phase, asking users to locate a specific trigger in the OA and WEA tables, as opposed to a specific workplace.

Phase 3:

Pre- and postknowledge questionnaire results are summarized in Table 3. They again provided positive feedback about the website’s layout and informational content. This time, all were satisfied with design and text density but still desired more pictures. They also desired more information about WRA, and a listing of explicit website aims on the home page. Given the increased content in the website, participants now occasionally became lost on different menu levels, and requested improvements to the tab structure to prevent this. The most commonly listed newly learned topics were identical to the first four in phase 2. Quantitative results from task completion as well as SUS scores are presented in Table 3.

To address ongoing difficulties with task 4, a search function was created enabling users to search the entire website. Also specified was a tab labelled ‘Triggers and Jobs’ with specific OA and WEA webpages under a subtab. The homepage introductory message was removed, the tab structure was simplified, borders were added around different sections on each page to increase their visual separation, and descriptions under ‘Compensation System’ and ‘My Rights’ sections were separated into individual webpages under a new section labelled ‘What Are My Rights?’

Phase 4:

Two asthma educators reviewed the website and found it to be very effective. Overall, they were satisfied with the amount and usefulness of provided information, and the ease and flow of information presentation. They had no difficulties with task completion and suggested reducing the literacy level to a grade 6 to 8 (21) level from a baseline grade 12 level. Similar changes have been recommended in previous reports and have been linked to increased website uptake (20,29). Accordingly, all content was revised to a grade 8 reading and comprehension level.

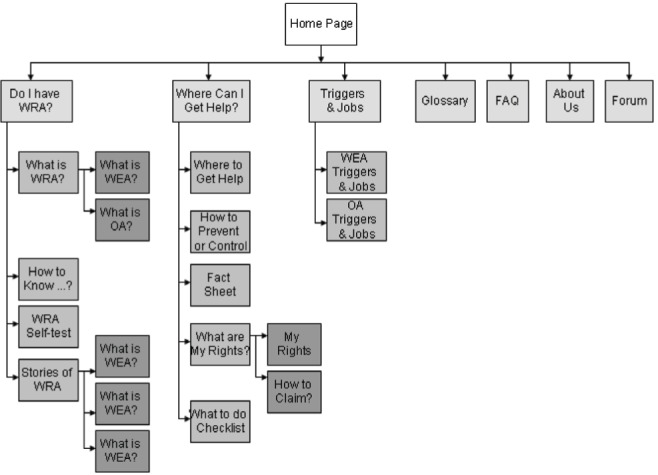

A screenshot of the final website is depicted in Figure 2 and a web content map in Figure 3. Other unique website features include a printable WRA information sheet for patients to deliver to their physicians (to prompt physicians to consider a WRA diagnosis); a printable fact sheet for colleagues (informing them of what steps to take in the event of a serious workplace asthma attack); and hover pop-up definitions for uncommon terms. The website is available for viewing at <http://lung.ca/workrelatedasthma/>. It should be noted that the discussion forum has not yet been added, pending official website launch with a formal user registration process, and a frequently asked questions section has not yet been posted because it will be built based on user questions.

Figure 3).

Web content map. FAQ Frequently asked question; OA Occupational asthma; WEA Work-exacerbated asthma; WRA Work-related asthma

DISCUSSION

We developed a dedicated WRA educational website for young adults with asthma. Development was based on best format and content evidence complemented by serial changes based on data gathered iteratively from target group members.

Given evidence that visual appeal and design influence early user decisions to reject or mistrust health informational websites (25), particular attention was devoted to the website’s design itself, adhering to evidence-based, visual design criteria used to evaluate the quality of health websites (Table 1). The SUS has been shown to be a robust and reliable measure of interface and website usability (30). Although all SUS scores were favourable, they were surprisingly lower in phase 3 than in phase 2, contrary to task completion scores and qualitative usability feedback. This may be because four of five phase 2 users had interacted with a version of the website in phase 1 and, thus, had more website familiarity than naive users in phase 3. The mean overall SUS rating assigned in phase 2 corresponded to an adjectival description between ‘Good’ and ‘Excellent’, whereas the mean SUS in phase 3 placed usability between ‘OK’ and ‘Good’ (30).

The Internet is a well-suited educational medium for young adults because they have a high rate of access and the required technical ability, and perceive computers to be an attractive leisure activity (31). Our interactive online tool enables dynamic and flexible content presentation that can rapidly be modified to reflect new data and/or changing user needs. It is self-initiated and convenient, has 24 h accessibility and increased privacy of access (access need not occur in a physician or guidance counsellor’s office/classroom). These features address many of the health system barriers to conventional asthma education, including limited availability of practitioner time and reimbursement, the need for sustainable access across various settings (school, home, clinic) and the need to adjust content to meet individual patients’ needs (32). Qualitative studies have demonstrated the willingness of patients with asthma, and of young adults in particular, to use web-based asthma education (33). Quantitative studies have shown high levels of acceptance, improved knowledge, and improved asthma-related health outcomes in children and adolescents exposed to web-based asthma education (34). Furthermore, adolescents with asthma value peer information sharing as part of learning (33). Programmed social interaction features support friendships and provide peer supports to those who may otherwise feel isolated due to their health condition (31). Accordingly, our discussion forum will prove valuable in enabling open communication and learning among peers about particular asthma-related workplace dangers and mitigating strategies.

Our website could be used as part of a knowledge translation intervention to address several known barriers to prevention, diagnosis and management of WRA. First, patients themselves remain largely unaware of the potential interaction between asthma and the work-place, which acts as a barrier to both prevention and early diagnosis (35). Our website addresses patient knowledge and behaviour gaps directly. Next, even when they were aware of work exposure risks, patients were statistically more likely to discuss the impact of their asthma on their future career with their parents or friends than with their practitioner (12,35). Furthermore, practitioner ascertainment of occupational histories among patients with asthma is often incomplete and discordant with patient-report (36). This likely reflects inadequate physician awareness and knowledge of WRA due to lack of training. Our website encourages patients to risk-stratify themselves using a self-test and to raise the possibility of WRA with their health care practitioner with the help of a simple, printable information resource. This resource not only acts as a tool for patient-mediated knowledge translation, but also addresses practitioner gaps in both awareness and knowledge.

Our study had several limitations. First, the sample size was small. More focus groups may have been beneficial in increasing reliability, saturation in qualitative themes and external validity. Knowledge test scores were very high at baseline, suggesting that this test was too easy, creating a ceiling effect that prevented us from demonstrating increased knowledge with website use. A volunteer bias for participants with an interest in and/or pre-existing knowledge of WRA may also partly account for the high baseline knowledge scores. Volunteers may also have had a higher level of concern about their asthma and higher literacy than average patients; this was not formally assessed. Although we did not receive any negative feedback regarding readability of the website from participants, we did attempt to address this possibility by reducing the website’s reading level from a grade 12 to a grade 8 level after all focus groups were completed. In terms of external validity, we acknowledge that it would be difficult for 10 subjects to adequately represent the full spectrum of the young adult asthma population. However, subject medications and health care utilization data suggest that patients across a spectrum of asthma severity, from mild to severe disease, were included in the study. A majority of subjects had poorly controlled asthma according to Canadian Asthma guidelines (37); however, this is similar to the Canadian asthma population at large (38). Our sample was also split evenly between students and workers. Although all subjects were in their 20s, we would not expect the preferences of young adults in their late teens to be systematically different than those of our subjects.

Future research should measure the effects of this tool on actual patient behaviour and health outcomes in a larger pool of participants. Ultimately, this resource could be disseminated and tested through job-educational and guidance-counselling sessions in schools and continuing education settings, through links on online job-search sites such as ‘Workopolis’, as well as asthma, lung health and occupational health websites, and by various health care professionals.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Amy Henderson, Manager of Health Communications, and Janis Haas, Director of Marketing and Communications, both of the Canadian Lung Association, for assistance in adjusting the reading level of this program, and the Asthma Society of Canada for reviewing earlier versions. They also thank the educators and the young adults with asthma who assisted in the evaluation of earlier versions of the website.

APPENDIX 1. ADDITIONAL WEBSITE SCREENSHOTS

Figure 1).

Prototype website baker’s asthma case description (no trigger page was available at this stage)

Figure 2).

Phase 2: Website home page

Figure 3).

Phase 2: Website Common Triggers page

Figure 4).

Phase 3: Website home page

Figure 5).

Phase 3: Website Common Triggers page

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS: SG and SMT conceptualized the study. SGK ran focus groups, collected, and analyzed feedback, and developed website prototypes. SMT, GML and MR developed the database of information to be included on the website. SGK and MC designed and organized user testing sessions. AL advised on web design. SGK and SG analyzed results and prepared the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

FUNDING: This research was supported by WorkSafeBC and the WHSCC of Newfoundland & Labrador. Dr Gupta is supported by the Office of Continuing Education and Professional Development in the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario.

REFERENCES

- 1.Moorman JE, Rudd RA, Johnson CA, et al. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) National surveillance for asthma – United States, 1980–2004. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2007;56:1–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Henneberger PK, Redlich CA, Callahan DB, et al. An official American Thoracic Society statement: Work exacerbated asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184:368–78. doi: 10.1164/rccm.812011ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liss GM, Buyantseva L, Luce CE, Ribeiro M, Manno M, Tarlo SM. Work-related asthma in health care in Ontario. Am J Ind Med. 2011;54:278–84. doi: 10.1002/ajim.20935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schmier JK, Manjunath R, Halpern MT, Jones ML, Thompson K, Diette GB. The impact of inadequately controlled asthma in urban children on quality of life and productivity. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2007;98:245–51. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60713-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vandenplas O, Toren KB. Health and socioeconomic impact of work-related asthma. Eur Respir J. 2003;22:689–697. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00053203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Balmes J, Becklake M, Blanc P, et al. Environmental and Occupational Health Assembly, American Thoracic Society American Thoracic Society statement: Occupational contribution to the burden of airway disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167:787–97. doi: 10.1164/rccm.167.5.787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hendrick DJ. The world wide problem of occupational asthma. Clin Exp Allergy. 2001;31:1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Henneberger PK. Work-exacerbated asthma. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;7:146–51. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0b013e328054c640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cullinan P, Tarlo S, Nemery B. The prevention of occupational asthma. Eur Respir J. 2003;22:853–60. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00119502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Work-Related Asthma – 38 States and District of Columbia. 2006–2009. MMWR. 2012 May 25;:375–8. < www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6120a4.htm. < www.webcitation.org/6AYbRGMo7> (Accessed April 1, 2013) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cochrane GM. Therapeutic compliance in asthma; its magnitude and implications. Eur Respir J. 1992;5:122–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bhinder S, Cicutto L, Abdel-Qadir HM, Tarlo SM. Perception of asthma as a factor in career choice among young adults with asthma. Can Respir J. 2009;16:e69–e75. doi: 10.1155/2009/810820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tarlo SM, Balmes J, Balkissoon R, et al. American College of Chest Physicians Consensus Statement: Diagnosis and management of work-related asthma. Chest. 2008;134(3 Suppl):1S–41S. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-0201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moscato G, Pala G, Boillat MA, et al. EAACI position paper: Prevention of work-related respiratory allergies among pre-apprentices or apprentices and young workers. Allergy. 2011;66:1164–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2011.02615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cline RJ, Haynes KM. Consumer health information seeking on the Internet: The state of the art. Health Educ Res. 2001;16:671–92. doi: 10.1093/her/16.6.671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sharps H, Rogers Y, Preece J. Interaction Design: Beyond Human-Computer Interaction. 3rd edn. West Sussex: Wiley & Sons; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koyani SJ, Bailey RW, Nall JR. Research-based web design & usability guidelines. US Department of Health and Human Services, Computer Psychology; 2004. < www.usability.gov/guidelines/> (Accessed April 1, 2013) [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bruseberg A, McDonagh-Philp D. Focus groups to support the industrial/product designer: A review based on current literature and designers’ feedback. Appl Ergon. 2002;33:27–38. doi: 10.1016/s0003-6870(01)00053-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gupta S, Wan FT, Newton D, Bhattacharyya OK, Chignell MH, Straus SE. WikiBuild: A new online collaboration process for multistakeholder tool development and consensus building. J Med Internet Res. 2011;13:e108. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Benigeri M, Pluye P. Shortcomings of health information on the Internet. Health Promo Int. 2003;18:381–6. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dag409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Graber MA, Roller CM, Kaeble B. Readability levels of patient education material on the World Wide Web. J Fam Pract. 1999;48:58–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oermann MH, Gerich J, Ostosh L, Zaleski S. Evaluation of asthma websites for patient and parent education. J Pediatr Nurs. 2003;18:389–396. doi: 10.1016/s0882-5963(03)00161-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lustria MLA. Can interactivity make a difference? Effects of interactivity on the comprehension of and attitudes toward online health content. Am Soc Inf Sci Technol. 2007;58:766–76. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cook DA, Levinson AJ, Garside S, Dupras DM, Erwin PJ, Montori VM. Instructional design variations in Internet-based learning for health professions education: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Acad Med. 2010;85:909–22. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181d6c319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sillence E, Briggs P, Fishwick L, Harris P. Trust and mistrust of online health sites. Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI’04), ACM; 2004; pp. 663–70. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Clark RC, Mayer R. E-Learning and the Science of Instruction: Proven Guidelines for Consumers and Designers of Multimedia Learning. 2nd edn. San Francisco: Pfeiffer; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Driscoll M, Tomiak GR. Web-based Training: Using Technology to Design Adult Learning Experiences. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass/Pfeiffer; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brooke J. SUS: A ‘quick and dirty’ usability scale. In: Jordan PW, Thomas B, Weerdmeester BA, McClelland AL, editors. Usability Evaluation in Industry. London: Taylor & Francis; 1996. pp. 189–94. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cotugna N, Vickery CE, Carpenter-Haefele KM. Evaluation of literacy level of patient education pages in health-related journals. J Community Health. 2005;30:213–9. doi: 10.1007/s10900-004-1959-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bangor A, Kortum PT, Miller JT. An empirical evaluation of the system usability scale. Int J Hum Comput Interact. 2008;24:574–94. [Google Scholar]

- 31.McPherson AC, Glazebrook C, Smyth AR. Educational interventions – computers for delivering education to children with respiratory illness and to their parents. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2005;6:215–26. doi: 10.1016/j.prrv.2005.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krishna S, Francisco BD, Balas EA, König P, Graff GR, Madsen RW. Randomized trial. Internet-enabled interactive multimedia asthma education program: A randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2003;111:503–10. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.3.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rhee H, Wyatt TH, Wenzel JA. Adolescents with asthma: Learning needs and internet use assessment. Respir Care. 2006;51:1441–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Runge C, Lecheler J, Horn M, Tews JT, Schaefer M. Outcomes of a Web-based patient education program for asthmatic children and adolescents. Chest. 2006;129:581–93. doi: 10.1378/chest.129.3.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Santos MS, Jung H, Peyrovi J, Lou W, Liss GM, Tarlo SM. Occupational asthma and work-exacerbated asthma: Factors associated with time to diagnostic steps. Chest. 2007;131:1768–75. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-2487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shofer S, Haus BM, Kuschner WG. Quality of occupational history assessments in working age adults with newly diagnosed asthma. Chest. 2006;130:455–62. doi: 10.1378/chest.130.2.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lougheed MD, Lemiere C, Ducharme FM, et al. Canadian Thoracic Society 2012 guideline update: Diagnosis and management of asthma in preschoolers, children and adults. Can Respir J. 2012;19:127–64. doi: 10.1155/2012/635624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.FitzGerald JM, Boulet LP, Kclvor RA, Zimmerman S, Chapman KR. Asthma control in Canada remains suboptimal: The Reality of Asthma Control (TRAC) study. Can Respir J. 2006;13:253–9. doi: 10.1155/2006/753083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]