Abstract

Background

Expression of tissue factor (TF) antigen and activity in platelets is controversial and dependent upon the laboratory and reagents used. Two forms of TF were described: an oxidized functional form and a reduced nonfunctional form that is converted to the active form through the formation of an allosteric disulfide. This study tests the hypothesis that the discrepancies regarding platelet TF expression are due to differential expression of the two forms.

Methods

Specific reagents that recognize both oxidized and reduced TF were used in flow cytometry of unactivated and activated platelets and western blotting of whole platelet lysates. TF-dependent activity measurements were used to confirm the results.

Results

Western blotting analyses of placental TF demonstrated that, in contrast to anti-TF#5, which is directed against the oxidized form of TF, a sheep anti-human TF polyclonal antibody recognizes both the reduced and oxidized forms. Flow cytometric analyses demonstrated that the sheep antibody did not react with the surface of unactivated platelets or platelets activated with thrombin receptor agonist peptide, PAR-1. This observation was confirmed using biotinylated active site-blocked factor (F)VIIa: no binding was observed. Likewise, neither form of TF was detected by western blotting of whole platelet lysates with sheep anti-hTF. Consistent with these observations, no FXa or FIXa generation by FVIIa was detected at the surface of these platelets. Similarly, no TF-related activity was observed in whole blood using thomboelastography.

Conclusion and Significance

Platelets from healthy donors do not express either oxidized (functional) or reduced (nonfunctional) forms of TF.

Keywords: hemostasis, factor VIIa, platelets, tissue factor, flow cytometry

1.1 Introduction

Blood coagulation is initiated at sites of vascular injury by formation of the tissue factor (TF)1/factor (F)VIIa complex which activates FIX and FX. FIXa assembles into the intrinsic FXase complex on the surface of activated platelets to generate additional FXa, while FXa assembles into platelet-bound prothrombinase to generate thrombin [1]. Thrombin amplifies, propagates and sustains the coagulant response through the recruitment of additional activated platelets to the site of injury, and activation of plasma coagulation factors [2]. Sequestration of TF from plasma under normal, physiological conditions by limiting its constitutive expression to subendothelial cells restricts thrombin generation to sites of vascular injury and prevents inappropriate clotting [3].

This paradigm has been challenged by studies suggesting the expression of TF activity and antigen by platelets [4-13]. In contrast, the data from our laboratory [14-16] have clearly demonstrated using well-characterized reagents and employing immuno-and functional assays that platelets do not express TF. The recent identification of a role for an allosteric disulfide in regulation of its coagulant function [17-21] led to the hypothesis that these discrepant data could be a result of differential expression of oxidized/reduced TF in platelets. Our previous studies utilized a monoclonal antibody directed against the active, oxidized form of TF. In the current study, these observations were extended by assessing platelet TF expression using a specific polyclonal antibody and active site-blocked recombinant FVIIa that both recognize the oxidized and reduced forms of TF.

1.2 Methods

1.2.1 Subjects

Healthy volunteer blood donors with normal coagulation histories were recruited and advised according to a protocol approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Vermont Human Studies Committee. Informed written consent was obtained from all subjects prior to blood collection.

1.2.2 Materials

Corn trypsin inhibitor (CTI) was isolated as previously described [22]. The monoclonal antibodies anti-FXI-2, anti-FIX-40, anti-FX-1D and anti-TF#5 [23] were obtained from the Biochemistry Antibody Core Laboratory (University of Vermont). Sheep anti-human TF (hTF) antibody was purchased from Haematologic Technologies, Inc. (Essex Junction, VT). The control mouse and sheep IgGs were bought from Jackson ImmunoResearch (West Grove, PA), respectively. Mouse IgG, sheep IgG, anti-TF#5, and sheep anti-hTF were conjugated to AlexaFluor488 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Anti-CD62-phycoerythrin (PE) was purchased from BD Biosciences (Franklin Lakes, NJ). Streptavidin-AlexaFluor488 was purchased from Invitrogen. Human Fc was purchased from EMD Millipore (Billerica, MA). Placental TF was purified and subsequently reduced and alkylated as described previously [17]. D-Phe-Pro-Arg-CH2Cl (FPRck) was produced in house. Human FX and FIX were isolated from fresh frozen plasma using anti-FX and anti-FIX mAb-coupled Sepharose [24]. FXa was a gift from Dr. R. Jenny (Haematologic Technologies, Essex, VT) and recombinant TF1-242 a gift from Dr. R. Lundblad (Baxter Healthcare Corp., Duarte, CA). Recombinant FVIIa (rFVIIa), a gift from Dr. U. Hedner (Novo Nordisk, Denmark), was active site blocked and biotinylated in house.

Streptavidin conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (HRP), prostaglandin E1, protease activated receptor (PAR) 1 agonist peptide (SFLLRN-NH2), lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and Arg-Gly-Asp-Ser (RGDS) were bought from Sigma (St. Louis, MO).

Chemiluminescence reagent was purchased from Perkin Elmer (Waltham, MA). Goat anti-mouse IgG (H+L)-horseradish peroxidase (HRP) and rabbit anti-sheep IgG (H+L)-HRP were purchased from SouthernBiotech (Birmingham, AL) and Affinity Biologicals (Ancaster, ON, Canada), respectively. Human monocytic cells THP-1 were from ATCC (Rockville, MD).

1.2.3 Blotting analyses

Reduced and alkylated or non-reduced and nonakylated placental TF, THP-1 lysates, or platelet lysates were resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) on 4-20% gradient gels under non-reducing conditions [25]. Following transfer to nitrocellulose [26], the resolved proteins were probed with mouse anti-TF#5 (5 μg/ml) or sheep anti-hTF (5 μg/ml). Primary antibody reactivity was detected using goat anti-mouse IgG (H+L)-HRP or rabbit anti-sheep IgG (H+L)-HRP (1:10,000 dilutions), respectively, followed by chemiluminesence. A similar protocol was used for western blotting of FIX and FX activation samples with anti-FIX-40 and anti-FX-1D monoclonal antibodies, respectively.

1.2.4 Preparation of THP-1 cells and platelets

Human monocytic cells THP-1 were cultured per the manufacturer's instructions. Cells (2.5 × 106 cells/mL) were stimulated with 250 ng/ml E. coli LPS (4 hr, 37 °C) to induce expression of TF [27]. For western blotting, cells (5 × 106 cells/mL) were lysed by multiple freeze/thaw cycles followed by dilution with 312.5mM Tris, pH 6.8, 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 50% glycerol, 0.05% bromophenol blue (5× SPB) (one part 5× SPB plus four parts cell lysate).

Platelets were isolated from human venous blood as described previously [28]. Platelets (1× 109 platelets/mL) were lysed with 1% triton X-100 and diluted with 5× SPB prior to SDS-PAGE and western blotting. For flow cytometric analyses, platelets were activated with PAR1 peptide (100 μM) (1×108 platelets/mL) for 15 or 120 min at 37 °C in the presence of RGDS to prevent platelet aggregation. Prior to flow cytometric analyses, platelets were either subjected to fixation with 2% paraformaldehyde (TF immunostaining) or activation was stopped by the addition of prostaglandin E1 (5 μM) (rFVIIa-biotin binding).

1.2.5 Flow Cytometric Analyses

LPS-stimulated THP-1 cells (1 × 106/mL) or unactivated and activated platelets (1 × 107/mL) were incubated with 0.1 μM sheep anti-hTF-AlexaFluor488 or a control sheep IgG-AlexaFluor488 (45 min, ambient temperature) in the presence of 10 μg/mL human Fc. In other experiments, LPS-stimulated THP-1 cells or platelets were incubated with 0 or 10 nM biotinylated active site-blocked rFVIIa (20 min, ambient temperature). Following centrifugation, the dry cell pellets were incubated with streptavidin-AlexaFluor488 (10 μg/mL, 45 min, ambient temperature).

Following extensive washing the cells were subjected to fixation with 2% paraformaldehyde and stored at 4 °C until flow cytometric analyses. Cells (10,000) were analyzed on a BD LSRII flow cytometer. Platelet activation was confirmed by immunostaining with anti-CD62-PE. The data were analyzed using FlowJo (version 7.6.5) software.

1.2.6 TF Activity Measurements

TF-dependent FXa and FIXa generation were determined as described previously [16, 29]. Briefly, platelets (2×108/mL) were incubated with 10 nM or 100 nM rFVIIa and 100 μM PAR1 peptide for 15 or 120 min at 37°C prior to the addition of FX (170 nM) or FIX (90 nM). The rate of FXa generation was determined by chromogenic assay and western blotting. FIXa generation was also assessed by western blotting. Control reactions used TF1-242 relipidated into 80% phosphatidylcholine/20% phosphatidylserine containing vesicles (PCPS) [30, 31] (20 pM TF/100 μM PCPS) as a TF source.

1.2.7 Thromboelastography (TEG)

Fresh whole blood was added to a TEG cup containing CTI (100 μg/mL) and anti-FXI-2 (667 nM) to block the contact pathway of blood coagulation, in the presence or absence of PAR1 peptide (100 μM) and anti-TF#5 (667 nM). In one experiment, platelet rich plasma (PRP), reconstituted to contain a three-fold physiological platelet concentration (656 × 106/mL) was used in place of whole blood. Analysis was carried out on each sample using a TEG Haemoscope 5000 (Haemonetics, Braintree, MA) at 37°C. TEG parameters were extracted using TEG V4 software (Haemonetics). Reactions were quenched after 70 minutes with an inhibitor cocktail (50 mM EDTA, 20 mM benzamidine, 100 μM FPR-ck). The samples were subjected to centrifugation, and the soluble material was frozen at -80°C until analysis of thrombin-antithrombin (TAT) complex [32].

1.3 Results

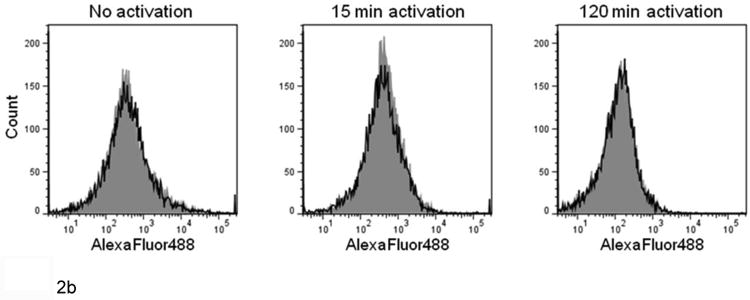

Previous observations have clearly demonstrated that unactivated platelets and platelets activated under different conditions do not express TF when analyzed by highly sensitive activity assays and flow cytometry using a well-characterized anti-TF antibody, anti-TF#5 [14-16]. Western blotting analyses of reduced, alkylated (reduced) and non-reduced, nonalkylated (oxidized) placental TF demonstrated that this antibody recognizes only the oxidized (active) form of TF (Fig. 1; mouse anti-TF#5). In contrast, a sheep polyclonal antibody directed against human TF (sheep anti-hTF) recognizes both oxidized and reduced forms of the protein (Fig. 1). As platelets (unactivated and activated) do not express active (oxidized) TF as demonstrated by functional assays and flow cytometry using anti-TF#5 [14-16], the expression of the inactive (reduced) form of TF by platelets was examined. Reactivity of sheep anti-hTF with cell surface expressed TF was confirmed using LPS-stimulated THP-1 cells. Flow cytometric analyses demonstrated substantial immunostaining of these cells with sheep anti-hTF conjugated to AlexFluor488 as compared to cells stained with the control sheep IgG-AlexaFluor488 used at the same concentration and same dye to protein ratio (Fig. 2A). In contrast, no reactivity with unstimulated THP-1 cells was observed consistent with a lack of cell surface expressed TF (data not shown). Similarly, no expression of TF by unactivated platelets or platelets activated with PAR1 agonist peptide (SFLLRN) for 15 min or 2 hr was observed despite maximal P-selectin expression (Fig. 2B). These platelets activation conditions were chosen as they mimic those shown previously by others to elicit platelet TF expression.

Figure 1. Antibody recognition of oxidized and reduced forms of TF.

Placental tissue factor (3 ng), resolved by SDS-PAGE under nonreducing (Ox) conditions or following reduction and alkylation (Red), was analyzed by western blotting using mouse anti-TF#5 and sheep anti-hTF antibodies. The numbers on the left denote the migration of the molecular weight markers. Mrapp placental tissue factor = 42 kDa. The higher molecular bands represent TF dimers (>90 kDa) and multimers (>150 kDa).

Figure 2. TF expression by lipopolysaccharide-stimulated monocytes and platelets.

(A) Lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated THP-1 cells (1 × 106/mL) or (B) platelets (1 × 107) were incubated with sheep anti-hTF-AlexaFluor488 (black line) or control sheep IgG-AlexaFluor488 (shaded histogram). Washed and fixed cells were analyzed by flow cytometry as described. No TF (oxidized or reduced) expression by platelets was observed.

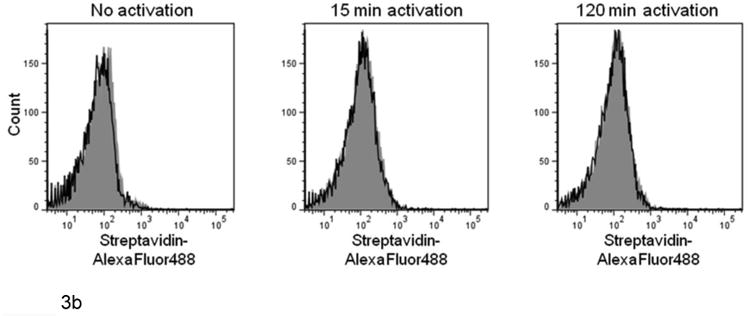

Further experiments using biotinylated, active site blocked rFVIIa confirmed these observations. Previous studies demonstrate that rFVIIa binds to both the oxidized and reduced forms of placental TF in a solid phase binding assay [17]. Following biotin-FPR-ck incorporation into the active site, rFVIIa reactivity with cell surface expressed TF was confirmed by flow cytometry. Positive reactivity was observed when LPS-stimulated THP-1 cells were incubated in the presence but not absence of biotinylated active site-blocked rFVIIa followed by streptavidin-AlexaFluor488 (Fig. 3A). Unstimulated THP-1 cells were negative (data not shown). As was observed above using sheep anti-hTF, there was no reactivity with unactivated or activated platelets confirming that TF antigen is not expressed by platelets under these conditions (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3. FVIIa binding to lipopolysaccharide-stimulated monocytes and platelets.

(A) LPS-stimulated THP-1 cells (1 × 106/mL) or (B) platelets (1 × 107/mL) were incubated with 0 (shaded histogram) or 20 nM biotinylated, active site-blocked rFVIIa (black lines) (20 min, ambient temperature). FVIIa binding was detected with streptavidin conjugated to AlexaFluor488 (10 μg/mL, 45 min, ambient temperature). Washed and fixed cells were analyzed by flow cytometry as described. No FVIIa binding to platelets was observed.

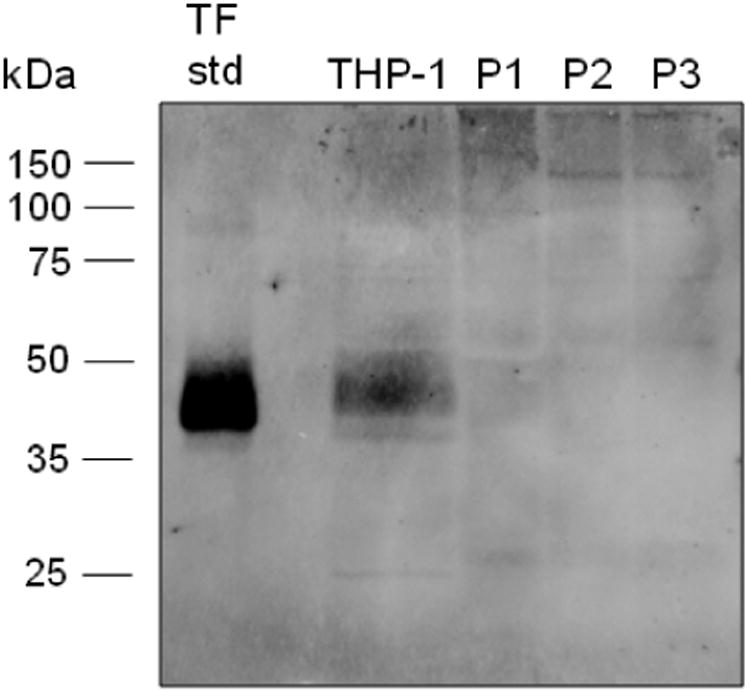

The absence of platelet TF was also demonstrated by western blotting. For these studies, platelet lysates were prepared using 1% triton X-100 and thus contain all cytoplasmic and granule contents. Placental TF was used as a positive control (Fig. 4; TF std). TF antigen was readily detected in THP-1 cell lysates by immunoblotting using anti-sheep anti-hTF (Fig. 4; THP-1). In contrast, no TF was detected in platelet lysates prepared from three different donors using these antibodies (Fig. 4; P1, P2, and P3). Identical results were achieved using antiTF#5 (data not shown).

Figure 4. Western blotting analyses of whole cell lysates.

Placental tissue factor (3 ng) (TF std), whole THP-1 cell lysates (1.2 × 106 cells/mL) (THP-1), and whole platelet lysates (8 × 108 platelets/mL) were resolved by SDS-PAGE under nonreducing conditions and analyzed by western blotting using sheep anti-hTF antibodies. The numbers on the left denote the migration of the molecular weight markers. Mrapp placental tissue factor = 42 kDa.

Well-characterized functional- and immuno-assays were subsequently used to assess TF activity. In marked contrast to chromogenic assays performed using relipidated TF in which substantial FXa generation by the extrinsic FXase was observed (∼2 pmol/L FXa/sec), no detectable FXa (<0.1 pmol/L FXa/sec) was generated when PAR1 activated platelets were used as the possible TF source (Fig. 5), even at concentrations of FVIIa as high as 100 nM (data not shown). Similarly, no FXa or FIXa generation was observed when activated platelets were used as the TF source in western blotting analyses (data not shown). These observations were confirmed using thromboelastography (TEG) [33]. This assay utilizes a well-characterized TF reagent and contact pathway inhibited blood or PRP, and can be used to elucidate the processes involved in fibrin formation and lysis by defining the physical properties of the clot [34]. TEG analysis of clot formation in contact pathway inhibited whole blood from four healthy donors was determined in the presence of PAR1 peptide and in the presence and absence of anti-TF#5 to ascertain a role for platelet TF in clot formation (Table 1). In the absence of any stimulation, the time to clot formation (R-time) was prolonged due to the contact pathway inactivation by CTI and anti-FXI-2. Intentional platelet activation with PAR1 peptide substantially shortened the R-time consistent with the exposure of coagulation protein binding sites and release of various hemostatic proteins from α- and dense granules [35]. In addition, release of platelet polyphosphates from dense granules accelerate FXI activation and consequently thrombin generation [36]. Addition of anti-TF#5 did not prolong the R-time or decrease the clot strength (MA, maximum amplitude). Subsequent measurements of the amounts of TAT formed over the course of the experiments also demonstrated no effect of the added antibody on thrombin generation.

Figure 5. Activated platelets do not express TF-related activity.

Platelets (2 × 108 platelets/mL) (○) were incubated with FVIIa (10 nM) and PAR1 (100 μM). Reactions were initiated by the addition of FX at its plasma concentration (0.17 μM). Formation of FXa was determined by chromogenic assay. Control reactions used relipidated TF1-242 (•).

Table 1.

The effects of anti-TF#5 on whole blood TEG and TAT formation.

| R-time (min) | MA (mm) | TAT (nM) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unactivated | |||

| CTI, anti-FXI | 68.3±9.2 | --- | 72.8±28.4 |

| CTI, anti-FXI, anti-TF#5 | 53.9±11.7 | --- | 84.4±35.3 |

| PAR1 activated | |||

| CTI, anti-FXI | 15±2.5 | 60.6±6.2 | 297.1±90.8 |

| CTI, anti-FXI, anti-TF#5 | 14.7±1.8 | 59.1±7.4 | 302.0±83.0 |

Fresh whole blood was added to a TEG cup containing CTI and anti-FXI-2 ± PAR1 and/or anti-TF#5, and clot formation parameters were measured. Quenched blood aliquots were used for the TAT quantitation. The data represent the mean ± SD from four donors assayed in duplicate. R-time; clot time; MA; maximum amplitude; TAT; α-thrombin-antithrombin III complex.

1.4 Discussion

To resolve the ongoing platelet TF controversy, experiments were performed to determine if platelets from normal donors express TF either in its active (oxidized) or the inactive (reduced) form [16]. Using a well-characterized anti-TF antibody that recognizes both the reduced and oxidized forms of human TF, no reactivity with unactivated platelets or platelets activated under transient or more prolonged conditions was observed. These results were confirmed by the TEG assay [32]. Furthermore, neither oxidized nor reduced TF were observed in platelet lysates by western blotting. Taken together the data clearly demonstrate that platelets from healthy dondors do not express either the reduced or oxidized forms of TF prior to or following activation. These results are in contrast to several studies by Camera and colleagues who suggested based on flow cytometry that TF is expressed by activated platelets [11, 12, 37]. These studies utilized a commercially available anti-TF antibody (American Diagnostica 4507CJ, clone VIC7) and reported that TF expression by functionally active platelets was a rapid and dynamic process. We attempted to confirm these results using clone VIC7 as compared to anti-TF#5 and, in contrast, observed no TF expression by platelets activated with PAR1 under the same conditions used by Camera and colleagues [14]. In addition, flow cytometric analyses of the specificity of five commercially available anti-TF antibodies by Basavaraj and colleagues [38] demonstrated that clone VIC7 in particular exhibited a high degree of non-specific binding to platelets and microparticles. Most recently, Vignoli et al. reported that 10% of platelets in healthy donor blood express TF using a different commercially available antibody (Serotec) [39]. This antibody was also shown to exhibit substantial non-specific reactivity with platelets [38].

FVIIa at supraphysiological concentrations neither binds to platelets nor effects FX or FIX activation when activated platelets are used as the potential TF source, which further supports the conclusion that platelets from healthy individuals do not express TF. These data also support a previous study demonstrating that FVIIa function in hemophilia is dependent upon TF expression and platelet accumulation at the site of an injury [40]. In contrast to these observations, using a cell-based model of blood coagulation, Monroe and colleagues reported that FVIIa binds weakly to activated platelets (Kd = 90 nM), and initiates thrombin generation in the absence of TF [41]. It was further suggested that FVIIa binding to activated platelets is mediated by the glycoprotein Ib-IX-V complex [42] and it binds preferentially to platelets activated with dual agonists (so called “coated ” platelets) [43]. However, it is possible that at the concentration of FVIIa used in the current study (10 nM), which corresponds to the mean physiological concentration of FVII and represents the highest theoretically possible FVIIa concentration in vivo [44], binding to platelets would not be detected.

Several distinct sources of platelet TF have been proposed to exist. De novo synthesis of TF by platelets was first reported by Weyrich's laboratory in 2006 [9]. Similar observations were made by Panes et al [10]. In these studies, prolonged platelet activation with thrombin [9] or PAR1 peptide [10] led to apparent increases in expression of TF mRNA, protein and procoagulant activity, as well as accelerated clot formation using a variety of commercially available immune reagents, immunoassays and activity assays. Similar observations were made in response to live bacteria and bacterial products using platelets from normal individuals [45]. However, in addition to the current study, several studies from Osterud's and our laboratories, were unable to detect TF antigen or activity following prolonged platelet stimulation with PAR agonist peptides [14, 15, 46], calcium ionophore [16], or LPS [15, 46]. The data also preclude the notion that TF is stored in and released from platelets upon their activation as suggested previously by others [6, 13]. These studies reported expression of TF by resting and activated platelets using both flow cytometry and western blotting analyses. Following its release from activated platelets and platelet-derived microparticles [6, 13], this TF supposedly expressed coagulant activity. However, like the studies reported by Camera and colleagues, the majority of the experiments described in these two studies utilized the anti-TF antibody, clone VIC7, one of the anti-TF antibodies shown to exhibit substantial non-specific reactivity with platelets and microparticles [38].

The original hypothesis that was the impetus for this study is based on the premise that Cys186 and Cys209 in the extracellular domain of TF form an allosteric disulfide bond that regulates TF activity [17-21]. When these sulfhydrals are present in their reduced state, TF is inactive (encrypted). Upon oxidation, the resulting disulfide bond induces TF decryption and expression of activity. While this regulation of TF activity has been clearly demonstrated in both cells and purified systems, evidence for free thiols in TF in vivo remains elusive. Consistent with this, a reduced form of TF was not found in platelets in the current study.

1.5 Conclusions

These observations confirm that platelets do not express either the oxidized (functional) or reduced (nonfunctional) form of TF under normal hemostatic conditions, and support our previous contention that differences in TF assays and reagents may explain some of the discrepancies. However, a role for platelet-associated TF in pathological states is less clear as under certain conditions cells in contact with the blood (primarily monocytes) will express TF.

Highlights.

Expression of reduced and oxidized tissue factor by platelets was examined.

No expression on platelets was observed by flow cytometry.

Tissue factor could not be detected in whole platelet lysates by immunoblotting

Tissue factor-dependent factor Xa and IXa formation by platelets was not observed.

A role for platelet tissue factor in clot formation could not be detected.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Dan Herbstman for providing TEG instruments, Dr. Richard Jenny for human FXa, Dr. Roger Lundblad for his gift of TF1-242 and Dr. Ula Hedner for recombinant FVIIa. We also would like to thank Robert Elsman and Maya Aleshnick for their technical assistance. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant P01 HL46703 (S.B. and K.G.M.). B.A.B was supported by National Institutes of Health grant K02 HL91111.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used:TF, tissue factor; F, factor; CTI, corn trypsin inhibitor; hTF, human TF; PE, phycoerythrin; FPRck, D-Phe-Pro-Arg-CH2Cl; rFVIIa, recombinant FVIIa; PAR, protease activated receptor; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; RGDS, Arg-Gly-Asp-Ser; HRP, horseradish peroxidase; PCPS, 80% phosphatidylcholine/20% phosphatidylserine containing vesicles; TEG, thromboelastography; PRP, platelet-rich plasma; TAT, thrombin-antithrombin; SDS-PAGE, sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis; 5× SPB, 312.5mM Tris, pH 6.8, 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 50% glycerol, 0.05% bromophenol blue; Mrapp, apparent molecular weight; kDa, kilodalton.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Literature Cited

- 1.Kalafatis M, Swords NA, Rand MD, Mann KG. Membrane-dependent reactions in blood coagulation: role of the vitamin K-dependent enzyme complexes. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 1994;1227:113–129. doi: 10.1016/0925-4439(94)90086-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mann KG, Brummel K, Butenas S. What is all that thrombin for? J Thromb Haemost. 2003;1:1504–1514. doi: 10.1046/j.1538-7836.2003.00298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Drake TA, Morrissey JH, Edgington TS. Selective cellular expression of tissue factor in human tissues. Implications for disorders of hemostasis and thrombosis. Am J Pathol. 1989;134:1087–1097. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rauch U, Bonderman D, Bohrmann B, Badimon JJ, Himber J, Riederer MA, Nemerson Y. Transfer of tissue factor from leukocytes to platelets is mediated by CD15 and tissue factor. Blood. 2000;96:170–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zillmann A, Luther T, Muller I, Kotzsch M, Spannagl M, Kauke T, Oelschlagel U, Zahler S, Engelmann B. Platelet-associated tissue factor contributes to the collagen-triggered activation of blood coagulation. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 2001;281:603–609. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.4399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Siddiqui FA, Desai H, Amirkhosravi A, Amaya M, Francis JL. The presence and release of tissue factor from human platelets. Platelets. 2002;13:247–253. doi: 10.1080/09537100220146398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Falati S, Liu Q, Gross P, Merrill-Skoloff G, Chou J, Vandendries E, Celi A, Croce K, Furie BC, Furie B. Accumulation of tissue factor into developing thrombi in vivo is dependent upon microparticle P-selectin glycoprotein ligand 1 and platelet P-selectin. J Exp Med. 2003;197:1585–1598. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Del Conde I, Shrimpton CN, Thiagarajan P, Lopez JA. Tissue-factor-bearing microvesicles arise from lipid rafts and fuse with activated platelets to initiate coagulation. Blood. 2005;106:1604–1611. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-03-1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schwertz H, Tolley ND, Foulks JM, Denis MM, Risenmay BW, Buerke M, Tilley RE, Rondina MT, Harris EM, Kraiss LW, Mackman N, Zimmerman GA, Weyrich AS. Signal-dependent splicing of tissue factor pre-mRNA modulates the thrombogenicity of human platelets. J Exp Med. 2006;203:2433–2440. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Panes O, Matus V, Saez CG, Quiroga T, Pereira J, Mezzano D. Human platelets synthesize and express functional tissue factor. Blood. 2007;109:5242–5250. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-06-030619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Camera M, Brambilla M, Toschi V, Tremoli E. Tissue factor expression on platelets is a dynamic event. Blood. 2010;116:5076–5077. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-09-307306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Camera M, Frigerio M, Toschi V, Brambilla M, Rossi F, Cottell DC, Maderna P, Parolari A, Bonzi R, De Vincenti O, Tremoli E. Platelet activation induces cell-surface immunoreactive tissue factor expression, which is modulated differently by antiplatelet drugs. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23:1690–1696. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000085629.23209.AA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Muller I, Klocke A, Alex M, Kotzsch M, Luther T, Morgenstern E, Zieseniss S, Zahler S, Preissner K, Engelmann B. Intravascular tissue factor initiates coagulation via circulating microvesicles and platelets. Faseb J. 2003;17:476–478. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0574fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bouchard BA, Krudysz-Amblo J, Butenas S. Platelet tissue factor is not expressed transiently after platelet activation. Blood. 2012;119:4338–4339. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-01-403469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bouchard BA, Mann KG, Butenas S. No evidence for tissue factor on platelets. Blood. 2010;116:854–855. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-05-285627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Butenas S, Bouchard BA, Brummel-Ziedins KE, Parhami-Seren B, Mann KG. Tissue factor activity in whole blood. Blood. 2005;105:2764–2770. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-09-3567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krudysz-Amblo J, Jennings ME, 2nd, Knight T, Matthews DE, Mann KG, Butenas S. Disulfide reduction abolishes tissue factor cofactor function. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2013;1830:3489–3496. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2013.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ahamed J, Versteeg HH, Kerver M, Chen VM, Mueller BM, Hogg PJ, Ruf W. Disulfide isolerization switches tissue factor from coagulation to cell signalling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:13932–13937. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606411103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen VM, Ahamed J, Versteeg HH, Berndt MC, Ruf W, Hogg PJ. Evidence for activation of tissue factor by an allosteric disulfide bind. Biochemistry. 2006;45:12020–12028. doi: 10.1021/bi061271a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Versteeg HH, Ruf W. Tissue factor coagulant activity is enhanced by protein disulfide isomerase independent of oxidoreductase activity. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:25416–25424. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702410200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liang HP, Brophy TM, Hogg PJ. Redox properties of the tissue factor Cys186-Cys209 disulfide bond. The Biochemical journal. 2011;437:455–460. doi: 10.1042/BJ20110718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hojima Y, Pierce JV, Pisano JJ. Hageman factor fragment inhibitor in corn seeds: purification and characterization. Thrombosis research. 1980;20:149–162. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(80)90381-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Parhami-Seren B, Butenas S, Krudysz-Amblo J, Mann KG. Immunologic quantitation of tissue factors. J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4:1747–1755. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.02000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jenny R, Church W, Odegaard B, Litwiller R, Mann KG. Purification of six human vitamin K-dependent proteins in a single chromatographic step using immunoaffinity columns. Prep Biochem. 1986;16:227–245. doi: 10.1080/00327488608062468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Towbin H, Staehelin T, Gordon J. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1979;76:4350–4354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.9.4350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Butenas S, Gissel M, Bouchard BA, Brummel KE, Parhami-Seren B, Mann KG. Demystifying tissue factor. Blood (ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts) 2004;104:1936. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bouchard BA, Catcher CS, Thrash BR, Adida C, Tracy PB. Effector cell protease receptor-1, a platelet activation-dependent membrane protein, regulates prothrombinase-catalyzed thrombin generation. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:9244–9251. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.14.9244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lawson JH, Mann KG. Cooperative activation of human factor IX by the human extrinsic pathway of blood coagulation. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:11317–11327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cawthern KM, van't Veer C, Lock JB, DiLorenzo ME, Branda RF, Mann KG. Blood coagulation in hemophilia A and hemophilia C. Blood. 1998;91:4581–4592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Higgins DL, Mann KG. The interaction of bovine factor V and factor V-derived peptides with phospholipid vesicles. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:6503–6508. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Foley JH, Ferris L, Brummel-Ziedins KE. Characteristics of Fibrin Formation and Clot Stability in Individuals with Congenital Type IIb Protein C Deficiency. Thrombosis research. 2012;129:142–146. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2011.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Foley JH, Butenas S, Mann KG, Brummel Ziedins KE. Measuring the mechanical properties of blood clots formed via the tissue factor pathway of coagulation. Anal Biochem. 2012;422:48–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2011.12.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kupesiz A, Rajpurkar M, Warrier I, Hollon W, Tosun O, Lusher J, Chitlur M. Tissue plasminogen activator induced fibrinolysis: Standardization of method using thromboelastography. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2010;21:320–324. doi: 10.1097/MBC.0b013e32833464e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bouchard BA, Silveira JR, Tracy PB. Interactions between platelets and the coagulation system. In: Michelson AD, editor. Platelets. Academic Press; San Diego, CA: 2013. pp. 425–451. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Puy C, Tucker EI, Wong ZC, Gailani D, Smith SA, Choi SH, Morrissey JH, Gruber A, McCarty OJ. Factor XII promotes blood coagulation independent of factor XI in the presence of long-chain polyphosphates. J Thromb Haemost. 2013;11:1341–1352. doi: 10.1111/jth.12295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Camera M, Brambilla M, Boselli D, Facchinetti L, Canzano P, Rossetti L, Toschi V, Tremoli E. Response: functionally active platelets do express tissue factor. Blood. 2012;119:4339–4341. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Basavaraj MG, Olsen JO, Osterud B, Hansen JB. Differentional ability of tissue factor antibody clones on detection of tissue factor in blood cells and microparticles. Thrombosis research. 2012;130:538–546. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2012.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vignoli A, Giaccherini C, Marchetti M, Verzeroli C, Gargantini C, Da Prada L, Giussani B, Falanga A. Tissue factor expression on platelet surface during preparation and storage of platelet concentrates. Transfusion Medicine and Hemotherapy. 2013;40:126–132. doi: 10.1159/000350330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Butenas S, Brummel KE, Bouchard BA, Mann KG. How factor VIIa works in hemophilia. J Thromb Haemost. 2003;1:1158–1160. doi: 10.1046/j.1538-7836.2003.00181.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Monroe DM, Hoffman M, Oliver JA, Roberts HR. Platelet activity of high-dose factor VIIa is independent of tissue factor. Br J Haematol. 1997;99:542–547. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1997.4463256.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Weeterings C, de Groot PG, Adelmeijer J, Lisman T. The glycoprotein Ib-IX-V complex contributes to tissue factor-independent thrombin generation by recombinant factor VIIa on the activated platelet surface. Blood. 2008;112:3227–3233. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-02-139113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kjalke M, Kjellev S, Rojkjaer R. Preferential localization of recombinant factor VIIa to platelets activated with a combination of thrombin and a glycoprotein VI receptor agonist. J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5:774–780. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02389.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fair DS. Quantitation of factor VII in the plasma of normal and warfarin-treated individuals by radioimmunoassay. Blood. 1983;62:784–791. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rondina MT, Schwertz H, Harris EM, Kraemer BF, Campbell RA, Mackman N, Grissom CK, Weyrich AS, Zimmerman GA. The septic milieu triggers expression of spliced tissue factor mRNA in human platelets. J Thromb Haemost. 2011;9:748–758. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04208.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Osterud B, Olsen JO. Human platelets do not express tissue factor. Thrombosis research. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2013.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]