Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Spontaneous hemoperitoneum in healthy males is an extremely rare, life threatening emergency condition with high mortality and morbidity, if not diagnosed and managed early.

PRESENTATION OF CASE

We present a 33-year-old male who presented with hemoperitoneum following self-induced vomiting.

DISCUSSION

To suspect and diagnose the condition is a challenge for clinician if ambiguity in presentation prevails.

CONCLUSION

The most important strategy in management of equivocal cases is early surgical exploration to establish the diagnosis and treat accordingly.

Keywords: Hemoperitoneum, Abdominal apoplexy, Acute abdomen

1. Introduction

Acute abdomen due to spontaneous rupture of an intra-abdominal vessel is an extremely rare clinical condition particularly in otherwise healthy subjects. We report a case of acute abdomen in a young man due to spontaneous rupture of the posterior gastric artery.

2. Case report

A 33-year-old man came to Emergency Department with severe upper abdominal pain of 4–5 h duration. He had associated nausea but no vomiting. He had self-induced vomiting by using his finger to trigger his gag reflex. Following this, he developed severe upper abdominal pain radiating to his back in the midline. The pain was aggravated by lying supine and relieved by a lateral bending posture. There was no history of trauma or any medical disease, and he was not on any medication.

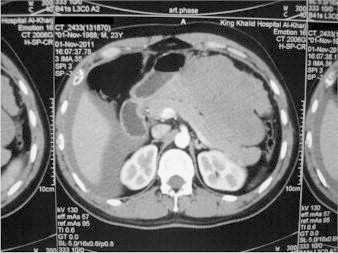

His general condition was fair with stable vital signs. He looked slightly pale and was in severe pain. His pulse was 77 beats per minute with a blood pressure of 110/70 mm Hg. He was afebrile with a respiratory rate of 22 breaths per minute. On abdominal examination, there was no gross distension but there was generalized guarding, tenderness and rebound tenderness consistent with acute peritonitis. His chest X-ray showed no free gas under the domes of diaphragm and the abdominal X-ray was unremarkable with a non-specific bowel gas pattern. Laboratory investigation was as follows: WBC – 10.5 × 10/μL, hemoglobin – 12.6 g/dL, platelet – 239 × 10 μL, glucose routine bloods were normal, apart from a low potassium (3.1 mmol/dL). The initial clinical impression was early acute pancreatitis or hollow viscous perforation. An ultrasound showed free fluid in his peritoneal cavity and computerized tomography (CT) scan of abdomen with oral and intravenous contrast reported a large well-defined soft tissue mass of about 10 cm × 12 cm posterior to the stomach, anterior and above the body and tail of pancreas with loss of fat plane from upper surface of body without enhancement or any blush (Fig. 1). A moderate amount of free fluid in the abdomen was noted. There was no free gas. Repeat laboratory investigations were unremarkable without any rising trend of amylase.

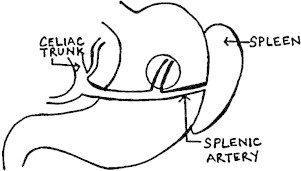

Fig. 1.

Picture showing the site of ruptured artery marked by circle.

In view of the clinical findings strongly suggestive of acute peritonitis and the suspicion of ruptured pancreatic mass after CT, exploratory laparotomy through midline incision was performed. His peritoneal cavity was full of free and clotted blood in the paracolic gutter, pelvis, perihepatic and perisplenic areas. On opening the lesser sac a large blood clot was found in the same region as suggested by CT abdomen. After clearing the clot a spurting vessel was seen which was found to be a bleeding posterior gastric artery (Fig. 2), controlled by ligation. There was no visible or palpable abnormality in his pancreas, spleen or posterior part of stomach. After control of the bleeding, the entire peritoneal cavity explored which appeared to be normal. His post-operative period was uneventful.

Fig. 2.

CT scan.

3. Discussion

Hemorrhage within the peritoneal cavity in itself is not uncommon, but intra-abdominal hemorrhage from a non-traumatic and non-iatrogenic cause is extremely rare. This condition has been named abdominal apoplexy or more recently, idiopathic spontaneous intraperitoneal hemorrhage (ISIH). Frederick P. Ross in a case report published in 1950 has stressed that this condition is a rare occurrence and that reporting of cases is warranted.1 He collected a total of 35 cases for his report. More recently Carmeci et al. found 110 cases reported in the literature between 1909 and 1998.2 Common causes of spontaneous abdominal hemorrhage are visceral (rupture of spleen, liver or kidney), gynecologic (rupture of ectopic pregnancy, or ovarian follicle), coagulopathy related conditions and vascular conditions. Examples of spontaneously ruptured vessels which have been reported include branch of middle colic artery,3 short gastric artery,4 and hepatic artery.5 The etiology of spontaneous rupture of vessels may be related to hypertension, arteriosclerosis, splanchnic artery aneurysm mainly of splenic and hepatic artery and the erosion of a vessel by an adjacent neoplastic or inflammatory process.

In our patient, the only obvious predisposing factor was self-induced vomiting. This led to the development of acute abdomen with abrupt onset of severe abdominal pain progressing to peritonitis, which finally turned out to be due to rupture of posterior gastric artery. Reports are available in the literature in which violent vomiting led to rupture of arteries supplying the stomach.6

There is no pathognomonic sign or symptom of abdominal apoplexy, however, Cushman and Kilgore have described the syndrome and believe that it can help in diagnosis.7 Signs and symptoms of spontaneous abdominal hemorrhage depend upon the site, volume and rate of bleeding. Usually it presents with sudden onset of severe abdominal pain, distension, signs of generalized peritoneal irritation and an acute drop of hematocrit level. Hypovolemic shock and discoloration around the umbilicus and flank might less commonly be found. The most important aid in the diagnosis is to maintain a high index of suspicion in ambiguous cases of acute abdomen. Hematocrit level obtained early may not suggest the diagnosis. Plain abdominal X-ray shows only nonspecific findings. Ultrasound abdomen can detect free fluid in the abdominal cavity and is particularly helpful in unstable cases. The availability of computerized tomography can be used to confirm the diagnosis with more accuracy in equivocal cases.

4. Conclusion

The primary aim of the treatment in cases of internal bleeding is to control the hemorrhage by ligating or repairing the involved vessel. In some clinically suspected cases of abdominal apoplexy if the patient is stable with more gradual onset, CT and visceral angiography can diagnose and localize bleeding vessel preoperatively. In such clinical setting, embolization may be a useful alternative to open operation. The most important strategy in management of equivocal cases is early surgical exploration to establish the diagnosis and treat accordingly.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Funding

None.

Ethical approval

The authors inform that they obtained a written consent from the patient.

Author contributions

Mohammad Ali Al Qarni: management decision, responsibilities, share in making the article as reviewed and history & examination of management details; Sarwer Jawaid: wrote the references and the article design.

Footnotes

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivative Works License, which permits non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

References

- 1.Frederick P.R. ‘Abdominal apoplexy’ complicated by mesenteric venous thrombosis: report of a case. Ann Surg. 1950;131:592–598. doi: 10.1097/00000658-195004000-00014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carmeci C., Munfakh N., Brook J.W. Abdominal apoplexy. South Med J. 1998;91:273–274. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199803000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cawyer J.C., Stone C.K. Abdominal apoplexy: a case report and review. J Emerg Med. 2011;40:e49–e52. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2007.11.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sun H.-P. Preoperative diagnosis and successful surgical treatment of abdominal apoplexy: a case report. Tzu Chi Med J. 2006;18:452–455. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parent B.A., Cho S.W., Buck D.G., Nalesnik M.A., Gamblin T.C. Spontaneous rupture of hepatic artery aneurysm associated with polyarteritisnodosa. Am Surg. 2010;76:1416–1419. doi: 10.1177/000313481007601230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ho M.P., Chang C.J., Huang C.Y., Yu C.J. Spontaneous rupture of the short gastric artery after vomiting. Am J Emerg Med. 2012;30(March (3)):513.e1–513.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cushman G.F., Kilgore A.R. The syndrome of mesenteric or subperitoneal haemorrhage (abdominal apoplexy) Ann Surg. 1941;114(4):672–681. doi: 10.1097/00000658-194110000-00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]