Abstract

Myotonic dystrophy type 1 (DM1), the most common form of adult-onset muscular dystrophy, is caused by an expanded (CTG)n repeat in the 3′ untranslated region of the DM protein kinase (DMPK) gene. The toxic RNA transcripts produced from the mutant allele alter the function of RNA-binding proteins leading to the functional depletion of muscleblind-like (MBNL) proteins and an increase in steady state levels of CUG-BP1 (CUGBP-ETR-3 like factor 1, CELF1). The role of increased CELF1 in DM1 pathogenesis is well studied using genetically engineered mouse models. Also, as a potential therapeutic strategy, the benefits of increasing MBNL1 expression have recently been reported. However, the effect of reduction of CELF1 is not yet clear. In this study, we generated CELF1 knockout mice, which also carry an inducible toxic RNA transgene to test the effects of CELF1 reduction in RNA toxicity. We found that the absence of CELF1 did not correct splicing defects. It did however mitigate the increase in translational targets of CELF1 (MEF2A and C/EBPβ). Notably, we found that loss of CELF1 prevented deterioration of muscle function by the toxic RNA, and resulted in better muscle histopathology. These data suggest that while reduction of CELF1 may be of limited benefit with respect to DM1-associated spliceopathy, it may be beneficial to the muscular dystrophy associated with RNA toxicity.

INTRODUCTION

Myotonic dystrophy type 1 (DM1) is the most common cause of adult-onset muscular dystrophy with an incidence of 1 in 8000 and is a multisystemic disorder (1). Major features of this autosomal dominant disorder are myotonia, muscle weakness, atrophy, smooth muscle dysfunction, cardiac defects and insulin resistance (2). DM1 is triggered by the expanded (CTG)n triple repeat in the 3′-untranslated region (UTR) of the DM protein kinase (DMPK) gene (1). This is transcribed to produce mutant RNAs containing CUG repeats that are retained in the nucleus to form RNA foci (3,4). This affects the nuclear and cytoplasmic activities of RNA-binding proteins such as muscleblind-like 1 (MBNL1) and CELF1 (5–8). MBNL1 binds to the expanded CUG repeat and co-localizes with the RNA foci, causing a local reduction of MBNL1 (6,7). Consequently, the activity of MBNL1 as a splicing regulator is impaired, resulting in aberrant alternative splicing of target genes (9). Consistent with the loss of MBNL1 function, an analysis of MBNL1 knockout mice (MbnlΔE3/ΔE3) showed that these mice developed some of the characteristic features of DM1, including misregulated mRNA splicing, muscle histopathological changes, cataracts and myotonia (10). Moreover, an adenoviral delivery of MBNL1 reversed the splicing changes and myotonia, again underscoring the importance of MBNL1 in the DM1 disease phenotype (11).

In addition to MBNL1, CELF1, a member of CUG-BP and ETR-3-like factor (CELF) family, is implicated in the disease process. CELF1 has been reported to have multiple functions in RNA metabolism including regulation of alternative splicing, RNA stability and translational regulation of its RNA targets (12–16). The mutant DMPK transcript is thought to activate PKC activity, leading to a hyperphosphorylation of CELF1 (17), resulting in the stabilization of and increased steady state levels of CELF1 in DM1 skeletal muscle and heart tissues. Transgenic mice overexpressing CELF1 showed neonatal lethality, skeletal muscle histological changes and misregulated splicing pattern observed in DM1 patients (18,19). Heart specific overexpression of CELF1 caused premature lethality, histopathological and echocardiographic abnormalities, and splicing defects (20). Two different transgenic mouse models which overexpressed CELF1 in skeletal muscle developed DM1 features. One mouse model showed that CELF1 responsive alternative splicing events were misregulated in skeletal muscle and that CELF1 affects muscle integrity and function (21). In the other model, muscular dystrophy, fiber type switching and delayed muscle development were seen in conjunction with increased levels of p21 and MEF2A (both of which are translational targets of CELF1) (18). Both of these models exhibited muscle loss, impaired muscle function and dystrophic muscle histology. These data demonstrate that increased CELF1 contributes to DM1 pathogenesis and suggests that reduction of CELF1 in a DM1 mouse model may have beneficial effects.

To test this, we generated CELF1 knockout mice that also carried an inducible toxic RNA transgene (5-313) (22). We found muscle function in these double-transgenic mice was protected from the effects of RNA toxicity and the histopathological features were milder as compared with mice carrying only the toxic RNA transgene, despite the fact that many alternative splicing events known to be misregulated in DM1 were not corrected by the absence of CELF1. This was associated with decreased Nkx2-5 levels in skeletal muscle from Celf1−/− mice expressing the toxic RNA, and corresponded to the milder histopathology of the muscle in these mice. Additionally, the protein levels of MEF2A and C/EBPβ were reduced in the absence of CELF1. These data suggest reduction of CELF1 may be beneficial to the muscular dystrophy associated with DM1.

RESULTS

Levels of CELF1 correlate with skeletal muscle histopathology in DM1

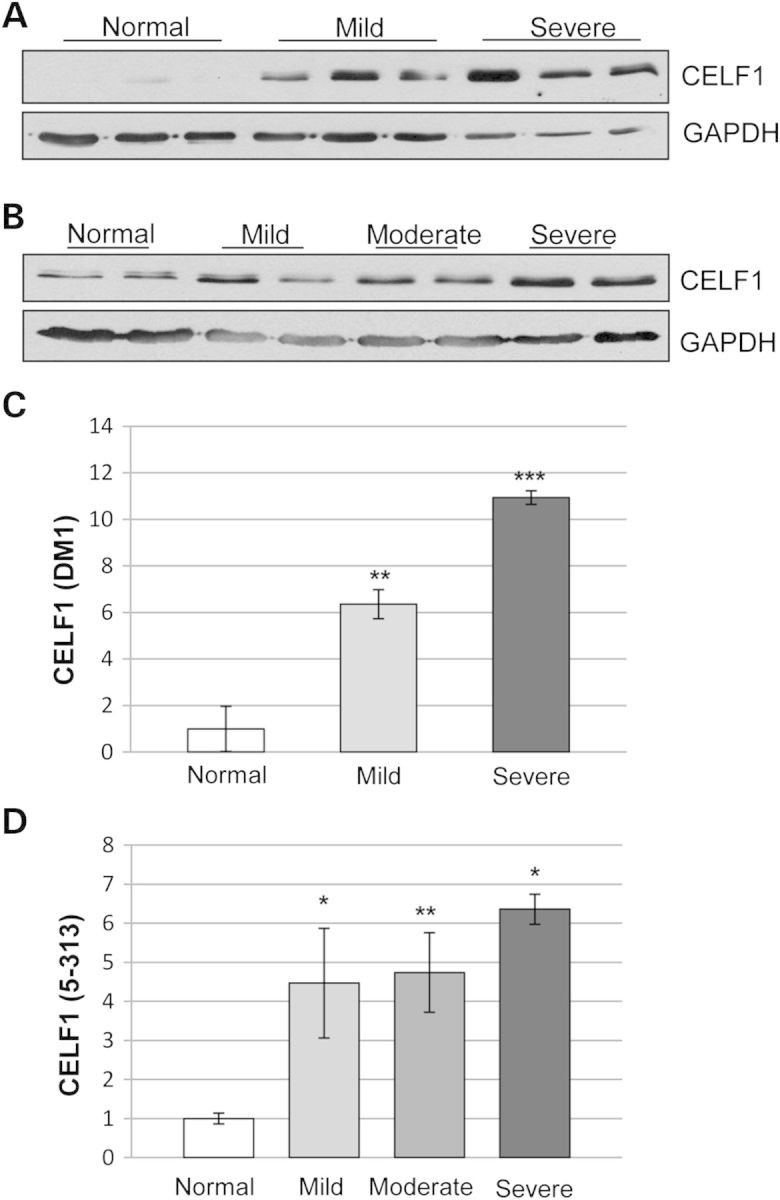

We first evaluated CELF1 levels in skeletal muscles from patients with DM1. Western blot analyses of muscle extracts showed increased CELF1 (up to 11-fold) that correlated well with muscle histopathology (Fig. 1A and C, Supplementary Material, Fig. S1A). No significant changes were seen in CELF mRNA levels between DM1 patient groups (Supplementary Material, Fig. S1B). Next, we investigated CELF1 in a doxycycline-inducible RNA toxicity mouse model of DM1 (5-313), which expresses an enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) gene fused to the DMPK 3′UTR (CTG)5 (22). CELF1 was increased in mice expressing the toxic RNA (between 2- and 6-fold) and the expression was highest in the muscles with the most severe histopathology (Fig. 1B and D, Supplementary Material, Fig. S1A). Thus, the mouse model accurately represented these aspects of the disease phenotype providing a basis for further investigations.

Figure 1.

CELF1 levels correlate with muscle histopathology in skeletal muscles of patients with DM1 and in the 5-313 mice. Graded muscle tissues from (A) human samples (normal = 3 unaffected adults, DM1 = 3 female and 3 male, ages between 47 and 55 years) and (B) the 5-313 mouse model (2 months old, 2 weeks induction, paraspinal muscles) was subjected to western blot for CELF1. CELF1 levels increased with severity of muscle histopathology in both DM1 individuals and the 5-313 mice. GAPDH was used as loading control. (C and D) Quantification for CELF1 protein levels using western blots for human (C) and mouse (D) tissues (n ≥ 3/group). A t-test was used to compare the results from normal tissues with each of the other groups (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.005). Representative images provided in Supplementary Material, Figure S1A.

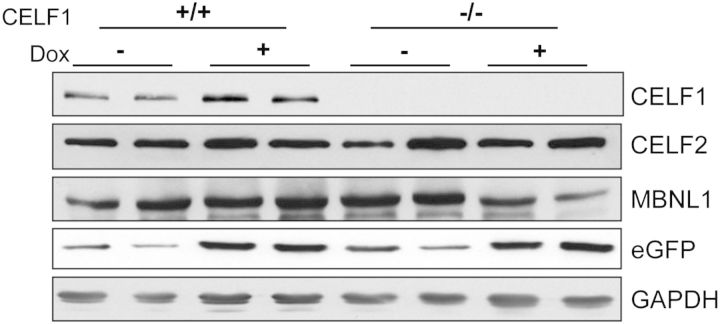

Absence of CELF1 does not affect MBNL1 or CELF2 in mice with RNA toxicity

To determine whether the reduction of CELF1 will improve the muscle pathology, 5-313 mice were crossed to Celf1−/− mice to generate Celf1−/−/5-313+/− mice and Celf1−/−/5-313+/+ mice. The ratio of +/+, +/− and −/− Celf1 mice from the intercrossing Celf1+/−/5-313 mice was different from the expected 1:2:1 Mendelian ratio at 21 days after birth (+/+:+/−:−/− = 24:62:14, P < 0.0001, χ2-test). This result is very similar to a previous Celf1−/− mice study (23). Celf1−/− mice were weak and developed cataracts (Supplementary Material, Fig. S2). Both Celf1−/−/5-313+/− and Celf1−/−/5-313+/+ were induced to express the toxic RNA using 0.2% doxycycline delivered in the drinking water for 5 months and 2 weeks, respectively. Celf1+/+/5-313-induced (+dox) and the appropriate uninduced (−dox) controls were also utilized. First, we analyzed the expression of Celf1 by quantitative RT–PCR (qRT–PCR) (Supplementary Material, Fig. S3A) and western blot (Fig. 2, Supplementary Material, Fig. S4A) to ensure that knockout mice did not express any CELF1. Celf1+/+/5-313 control mice expressed 2- to 6-fold more CELF1 after the induction of the toxic RNA, whereas CELF1 was not detected in Celf1−/−/5-313 mice even after the induction (Fig. 2). Induction of the transgene was confirmed by qRT–PCR (Supplementary Material, Fig. S3B) and western blot for eGFP (Fig. 2, Supplementary Material, Fig. S4B).

Figure 2.

Levels of relevant RNA-binding proteins. Protein extracts were prepared from paraspinal muscle tissues of mice and examined by western blots. Each lane represents a different mouse with the indicated genotype and induction condition. CELF1 was not detected in Celf1−/− mice. Western blot for CELF2, MBNL1 showed no change due to absence of CELF1 or presence of RNA toxicity. Western blot for eGFP confirmed transgene induction. GAPDH was used as loading control (see Supplementary Material, Fig. S4 for graphical representation of quantifications).

We tested whether any of the other CELF proteins compensated for the absence of CELF1. The level of Celf2 expression was determined using qRT–PCR (Supplementary Material, Fig. S3C) and western blot (Fig. 2, Supplementary Material, Fig. S4C). Both Celf2 mRNA and protein levels of CELF2 were unaffected by the absence of CELF1 and the presence of the toxic RNA. We also performed qRT–PCR to quantify the levels of Celf4 expression and found it was not expressed in skeletal muscle (data not shown). MBNL1 protein levels were assayed by western blot. Neither RNA toxicity nor the absence of CELF1 changed the levels of total MBNL1 protein in this mouse model (Fig. 2, Supplementary Material, Fig. S4D).

Absence of CELF1 preserves muscle function in the presence of RNA toxicity

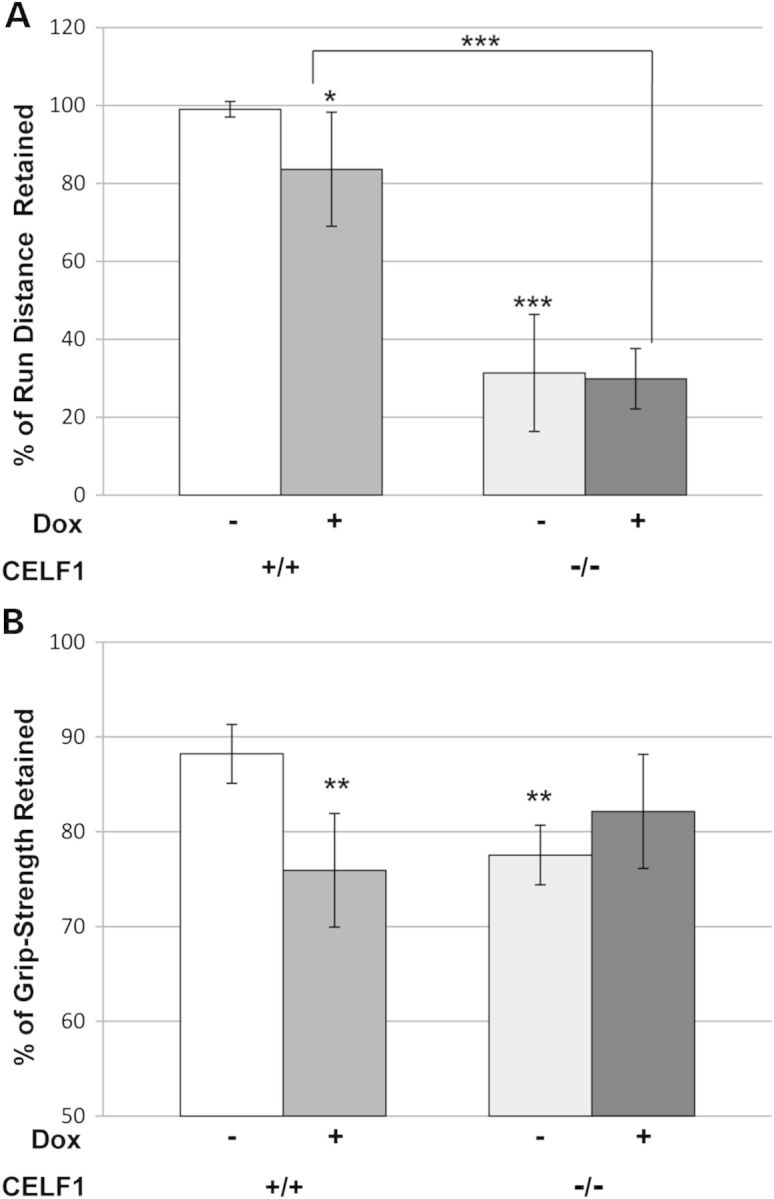

To analyze muscle function, we have established treadmill running and grip-strength tests. Celf1−/−/5-313 mice were weak even in the absence of the toxic RNA. Furthermore, the induction of RNA toxicity by doxycycline administration in 5-313+/+ mice made them much weaker leading to difficulties measuring the muscle function such as running and grip strength. Due to the high levels of the toxic RNA and disease severity in the 5-313+/+ mice, heterozygous 5-313 mice (5-313+/−), which express lower levels of the toxic RNA and develop a milder phenotype were used to generate Celf1−/−/5-313+/− mice, and tested for grip strength and their ability to complete a 752 meter forced run. After 5 months, the Celf1+/+/5-313+/− uninduced (−dox) group retained 99% of their run ability and 88.2% of their forelimb grip strength compared with their baseline function, whereas Celf1+/+/5-313+/− induced for 5 months with continued doxycycline administration (+dox) mice decreased to 83.6 and 75.9%, respectively (Fig. 3A and B) (P < 0.05). Celf1−/−/5-313+/− uninduced (−dox) mice retained only 31.3% of their run ability and 77.5% of their grip strength compared with their baseline function. However, the Celf1−/− mice expressing the toxic RNA maintained their run ability (29.9%) and their grip strength (82.1%) (Fig. 3A and B). Thus, unlike the RNA toxicity mice expressing CELF1 where we observed a significant decrease in function, the loss of CELF1 resulted in a preservation of muscle function in the 5-313+/− transgenic mice with RNA toxicity. We also examined cardiac function by electrocardiography (ECG) and myotonia using electromyography (EMG). The Celf1+/+ and Celf1−/− mice both developed prolonged PR intervals (an indicator of cardiac conduction defects) and myotonia by 2 weeks after induction (Supplementary Material, Table S1). The absence of CELF1 did not improve these phenotypes in the induced Celf1−/−/5-313+/− mice.

Figure 3.

Preservation of muscle function in Celf1−/−/5-313+/− mice. Celf1+/+/5-313+/− mice (n = 7) and Celf1−/−/5-313+/− mice (n = 5) were induced with 0.2% of doxycycline for 5 months. Uninduced mice were used as control (Celf1+/+/5-313+/− (n = 4), Celf1−/−/5-313+/− (n = 3)). (A) Mice were subjected to treadmill running and distance run was measured. The measurements were converted to % retained, as compared with a baseline measurement for each mouse. (B) Grip strength was assessed using a grip-strength meter. Data were expressed as force in grams and converted to % of grip-strength retained as compared with baseline. t-Tests for statistical significance were performed between Celf1+/+/5-313+/− (−dox) mice and either Celf1+/+/5-313+/− (+dox) mice or Celf1−/−/5-313+/− (−dox) mice. Comparison between Celf1+/+/5-313+/− (+dox) mice and Celf1−/−/5-313+/− (+dox) mice is as marked by brackets. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.005.

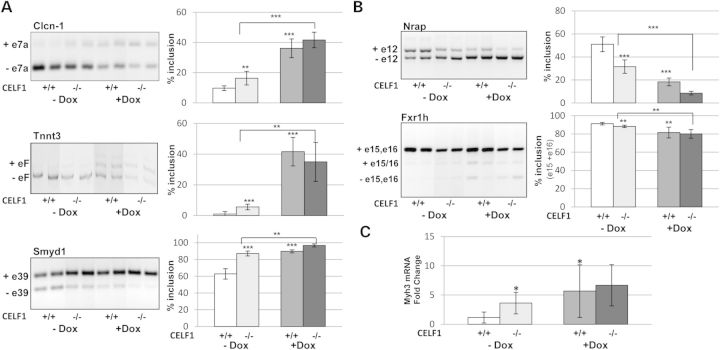

Absence of CELF1 does not correct misregulated alternative splicing

Misregulation of developmental alternative splicing transitions is a characteristic molecular feature of DM1, and CELF1 is thought to play an important role in these defects (6,19,24–26). Some of the splicing targets are antagonistically regulated by MBNL1 and CELF1 while others are reported to be specific to MBNL1 or CELF1 (13,27). To determine whether the removal of CELF1 restores the missplicing events affected by the toxic RNA, we analyzed various splicing targets which are abnormally spliced in the 5-313+/+ model. Aberrant splicing of Clcn-1 exon 7 is a key feature of DM1 and responsible for myotonia (28,29). Both Cubgp1+/+ and Cubgp1−/− mice showed misregulation of Clcn-1 splicing in the presence of the toxic RNA (Fig. 4A). Additionally, Tnnt3 exon F (the fetal isoform) and Smyd1 exon 39 were misregulated in skeletal muscle from both the induced +/+ and −/− mice (24,30,31) (Fig. 4A). Splicing targets reported to be CELF1 specific (Nrap exon 12 and Fxr1h exons 15, 16) were also examined and found to be misregulated by the toxic RNA in both the +/+ and −/− mice (13,21,32–34) (Fig. 4B). In summary, the alternative splicing events that are misregulated in this RNA toxicity model were not rescued by knockout of CELF1.

Figure 4.

Absence of CELF1 has no beneficial effects on the RNA splicing defects caused by RNA toxicity. (A) ClCn-1 exon 7a, Tnnt3-fetal exon and Smyd1 exon 39 were analyzed as mRNA splicing targets of DM1. (B) Nrap exon 12 and Fxr1h exons15-16 were assessed as CELF1-specific targets. Both Celf1+/+/5-313 and Celf1−/−/5-313 mice were tested in uninduced (−dox) and induced (+dox) conditions (n = 5 per group). The percentage of exon inclusion is graphically represented. (C) Expression of embryonic myosin heavy chain (Myh3) was examined by qRT–PCR. Significant differences were calculated and indicated as described in Figure 3. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.005 (t-test).

Interestingly, we found that the absence of CELF1 lead to a more embryonic pattern in all splicing events compared with mice expressing CELF1, even in the absence of the toxic RNA (Fig. 4A and B). To determine if the muscle from Celf1−/− mice is in an earlier embryonic/developmental stage, we looked at the expression of embryonic myosin heavy chain (Myh3) by qRT–PCR. Celf1−/− mice have 3.6-fold (P < 0.05) more Myh3 than Celf1+/+ mice in the absence of RNA toxicity and in the absence of any active degeneration/regeneration process (Fig. 4C). This is consistent with a more developmentally immature muscle. The levels increased to 6.7-fold after the induction of RNA toxicity (Fig. 4C), like the responses seen in mice with CELF1. These data suggest that CELF1 is not as strong a splicing modulator in RNA toxicity, and that other factors affected by the toxic RNA (e.g. MBNL1) may have a greater impact on the splicing events.

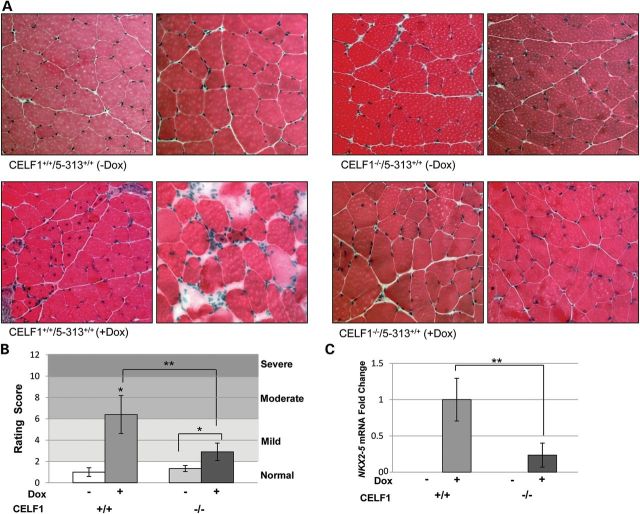

Absence of CELF1 leads to better muscle histology

Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining was performed on quadriceps muscles from Celf1+/+/5-313 and Celf1−/−/5-313 mice. These muscles were graded according to a histopathology scoring system we have developed in the lab. Both uninduced Celf1+/+ and −/− mice showed normal muscle histology with peripherally located nuclei and uniform fiber size (Fig. 5A). Atrophic fibers and inflammation were not observed in these muscles. By 2 weeks on 0.2% dox induction, Celf1+/+/5-313+/+ mice had characteristic DM1 histological features including increased central nuclei, variation in fiber size and nuclear clumping (Fig. 5A), as described previously (22). Their resulting average scores fell within the moderate severity range (Fig. 5B). However, the histology scores of induced Celf1−/− mice fell within the mild range. In these muscles, only 2–3% of the fibers contained central nuclei and these mice had minimal fiber size variation and no nuclear clumping (Fig. 5A). Thus, the severity of Celf1−/−/5-313+/+ induced (+dox) mice was milder than the Celf1+/+/5-313+/+ (+dox) (P < 0.01, Mann–Whitney U-test). Although the removal of CELF1 did not lead to completely normal muscle histology, it did result in significantly improved muscle histopathology.

Figure 5.

Improved muscle histopathology in CELF1−/−/5-313 and correlation with levels of Nkx2-5 mRNA. (A) Quadriceps femoris muscles were stained with H&E. Both uninduced Celf1+/+/5-313 and Celf1−/−/5-313 mice have normal muscle histology. Celf1−/−/5-313 (+dox) mice have milder histopathology compared with Celf1+/+/5-313(+dox) mice. (B) Histopathology grading shows Celf1−/− has a beneficial effect. Mann–Whitney U-test was used for statistical significance. Celf1+/+/5-313 (−dox) mice (n = 4) were compared with Celf1+/+/5-313 (+dox) mice (n = 5) or Celf1−/−/5-313 (−dox) mice (n = 3). Comparisons between induced (+dox) Celf1+/+/5-313 and Celf1−/−/5-313 mice (n = 5), and Celf1−/−/5-313 (−dox) mice and Celf1−/−/5-313 (+dox) mice are marked by brackets. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.005 (Mann–Whitney U-test). (C) Nkx2-5 mRNA level was assessed by qRT–PCR and relative expression is presented. Celf1−/−/5-313 mice (+dox) have five times less Nkx2-5 mRNA than Celf1+/+/5-313 mice (+dox) (n = 5); **P < 0.01 (t-test).

We have observed that Nkx2-5 level correlates with severity of the muscle histopathology in DM1 (data not shown) (35). We examined Nkx2-5 levels in Celf1+/+/5-313 and Celf1−/−/5-313 mice using qRT–PCR. Nkx2-5 mRNA levels in the induced Celf1+/+/5-313 mouse muscles were dramatically increased, whereas the levels were undetectable in the absence of RNA toxicity (Fig. 5C). However, the induced Celf1−/− mice had five times less Nkx2-5 expression relative to the induced Celf1+/+ mice (Fig. 5C). Downstream targets of Nkx2-5 such as Gata4, Nppa and Nppb (31) were assessed by qRT–PCR, and their levels were likewise affected (Supplementary Material, Fig. S5).

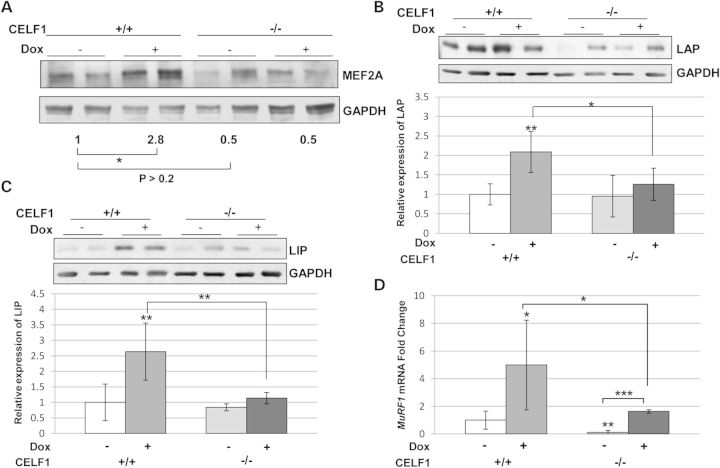

Translational targets of CELF1 are also affected in skeletal muscle

CELF1 functions as a translational regulator for several genes such as MEF2A and the C/EBPβ. It has been reported that transgenic mice overexpressing CELF1 have elevated levels of MEF2A and a delay in myogenesis (18). To examine whether the level of these translational targets are affected by the presence of RNA toxicity and CELF1 status, we analyzed the expression of MEF2A and C/EBPβ by western blotting. We found that CELF1 status had no significant effect on the levels of MEF2A in uninduced mice. However, the level of MEF2A increased in the presence of RNA toxicity in mice wild type for Celf1, and this effect was absent in the muscles of Celf1−/−/5-313+/+ (+dox) mice (Fig. 6A). Likewise, both of the isoforms of C/EBPβ (LAP and LIP) were consistently increased in Celf1+/+/5-313+/+ (+dox) mice with RNA toxicity in several independent experiments (Fig. 6B and C). Notably, the levels of both the LAP and LIP isoforms were not significantly induced in Celf1−/−/5-313+/+ (dox+) mice as compared with uninduced mice, and were significantly less than 5-313+/+ (dox+) mice that expressed CELF1 (Fig. 6B and C).

Figure 6.

MEF2A and C/EBPβ protein levels and expression of MuRF1 mRNA are affected by the absence of CELF1 in RNA toxicity. (A) Western blot for MEF2A. Numbers indicate relative intensity of bands (n = 4). MEF2A levels are not significantly affected by CELF1 deficiency in uninduced mice (P > 0.2, t-test). MEF2A increases significantly in Celf1+/+/5-313 with RNA toxicity (*P < 0.05, t-test). This is not seen in CELF1 deficient mice with RNA toxicity. (B) C/EBPβ LAP and (C) LIP isoforms were measured from western blots and relative protein expression are graphically represented. Both LAP and LIP levels were increased by RNA toxicity in induced 5-313 mice but not in Celf1−/−/5-313 mice (n = 5 per group). (D) Relative MuRF1 mRNA expressions were measured by qRT–PCR. Celf1+/+/5-313(+dox) mice (n = 6) have 5-fold more MuRF1 mRNA than uninduced mice (n = 7) and these levels are reduced to 1.6-fold in Celf1−/−/5-313(+dox) (n = 5). Significant differences were calculated and indicated as described in Figure 3. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.005 (t-test).

It has been previously reported that glucocorticoid treatment of mice increased C/EBPβ in skeletal muscle and regulated factors of muscle atrophy, and that knockdown of C/EBPβ reduced these levels in myoblasts (36). Given the improved muscle histology and decreased levels of C/EBPβ in the Celf1−/−/5-313 with RNA toxicity, we next analyzed atrogin-1 and MuRF1 mRNA levels in our mouse model. Neither the toxic RNA nor the absence of CELF1 influenced atrogin-1 mRNA in our mouse model (data not shown). However, RNA toxicity increased MuRF1 expression, and this was alleviated in Celf1−/−/5-313+/+ mice (Fig. 6D). Thus, the absence of CELF1 in the toxic RNA model mitigated the effect on translational targets such as MEF2A and C/EBPβ, which are thought to play a role in myogenesis and muscle atrophy.

DISCUSSION

Several studies using CELF1 transgenic mice support a role for CELF1 in DM1 pathogenesis (18–21,37). Transgenic mice overexpressing CELF1 reproduced splicing defects observed in individuals with DM1 and cardiac or muscle-specific expression also showed histological and functional DM1 features (19–21). Recently, a study using a dominant negative CELF1 protein showed rescue of splicing defects in a cell culture system and a DM1 mouse model (34). In addition, transgenic mice overexpressing a His-tagged CELF1 had increased mortality and evidence of disrupted myogenesis, a feature found in congenital DM1 (18).

These studies also supported the notion that the levels of CELF1 have a strong correlation with disease severity (18,21). Mice with 2- to 3-fold elevation of His-CELF1showed mild histological changes such as increased numbers of central nuclei, whereas higher levels (4- to 6-fold) leads to fiber type switching, and fiber size variation as well (18). In another study, using and inducible CELF1 transgenic mouse model, an 8-fold increase in CELF1 led to severe histopathology in 4 weeks, whereas a lower induction of CELF1 (2-fold) resulted in very mild muscle pathology (21). In our mouse model as well as patient tissues, we also see a clear correlation between CELF1 levels and muscle pathology (Fig. 1, Supplementary Material, Fig. S1). This suggests that reduced levels of CELF1 could result in better muscle histology.

As a prelude to performing experiments presented here, we had done a similar series of experiments using Celf1+/− (i.e. heterozygous knockout mice) and found no significant effects on the measured phenotypes or on CELF1 levels (data not shown). So, we examined the consequences of CELF1 deficiency in RNA toxicity by producing a complete knockout of CELF1 in our inducible RNA toxicity model. The lack of CELF1 (i.e. Celf1−/− mice) resulted in weak and small mice that had deficits in running on a treadmill and in grip-strength assays (Fig. 3). Also, these mice developed cataracts, a phenotype commonly seen in patients with DM1 (Supplementary Material, Fig. S2). This is unlikely to be related to the pathogenesis of cataracts in DM1 since CELF1 levels are elevated in DM1, not diminished or absent. Notably, the absence of CELF1 did not lead to myotonia, obvious cardiac conduction defects or obvious histopathology in skeletal muscles; phenotypes that are all prominent in DM1. However, there was some evidence for muscle immaturity based on RNA splicing patterns that resembled a more embryonic developmental stage and increased expression of embryonic myosin heavy chain isoforms (Fig. 4).

Having established a baseline phenotype for the CELF1 deficient mice, our goal was to see what effect CELF1 deficiency would have on our RNA toxicity model. CELF1 has been reported to have multiple functions in RNA metabolism including regulation of alternative splicing, RNA stability and translational regulation of its RNA targets and a number of molecular events have been associated with increased CELF1 and RNA toxicity. Using a systematic analysis of these associated phenotypes, we found that the absence of CELF1 had no obvious effect on the myotonia or cardiac conduction defects caused by RNA toxicity. Surprisingly, disrupted alternative splicing, a key feature of DM1 pathogenesis, is not corrected by reduction of CELF1. Not only general targets like Clcn-1 and Tnnt3 but also reported CELF1-specific targets (Nrap and Fxr1h) are misregulated by the toxic RNA even in the absence of CELF1. Though CELF1 and MBNL1 have been thought of as mutual antagonists, one possibility is that MBNL1 may be the stronger and more dominant modulator of alternative splicing defects in RNA toxicity associated with DM1. Although RNA foci and sequestration of MBNL1 are not observed in 5-313 mouse muscle, it is possible that submicroscopic foci exist due to an interaction with MBNL1. Using RNA IP of MBNL1 and associated RNAs, we have found that MBNL1 does indeed interact with the GFP-DMPK 3′UTR (CUG)5 RNA in our mice and both the normal and mutant DMPK mRNAs in human DM1 cell lines (data not shown). Although we did not see any compensatory effect of CELF2 or other CELF proteins, it is also possible that the toxic RNA could affect other unknown factors that may play a role in RNA splicing in this mouse model.

Though the CELF1 deficient mice started off weaker, the fact that there was no further diminution in the muscle function tests (treadmill run and grip strength) when RNA toxicity was induced in these mice, unlike the mice that were expressing CELF1 (Fig. 3), showed that CELF1 deficiency preserved muscle function despite the effects of RNA toxicity. Additionally, abnormal muscle histology in mice expressing the toxic RNA was restored towards normal, resulting in mice with milder histopathology (Fig. 5). Thus, the absence of CELF1 seems to have a clear protective effect against these adverse effects of RNA toxicity. As well, a number of molecular changes caused by RNA toxicity were minimized by the absence of CELF1. For instance, it has been previously proposed that the cytoplasmic function of CELF1 as a translational regulator could be disrupted by RNA toxicity (18). In this model, it is posited that CELF1 posttranscriptionally regulated various target mRNAs, such that in DM1, increased CELF1 in muscle tissue disrupted myogenesis via upregulation of translational targets such as MEF2A (18) and C/EBPβ (38). Indeed, in our RNA toxicity model, we see significant elevation of both MEF2A and C/EBPβ in skeletal muscle along with an increase in CELF1. Of note, we find that in the absence of CELF1 in our RNA toxicity mouse model, there is no significant increase in MEF2A and C/EBPβ and that this correlates with a beneficial effect on the histopathology and muscle function.

Though it is unclear how the effects on these translational targets could be affecting muscular dystrophy in our model, several recent studies have implicated C/EBPβ in myogenesis and muscle wasting. In a recent study, it was found that dexamethasone administration to cultured myoblasts led to increased C/EBPβ, up-regulated atrogin-1 and MuRF1 and reduced cell size (36). Treating the myoblasts with an siRNA against C/EBPβ resulted in reductions in C/EBPβ and MuRF1and was associated with preservation of cell size. RNA toxicity in our mouse model increases C/EBPβ and MuRF1 mRNA levels in skeletal muscle and is associated with muscle weakness, atrophy and histopathology. Of note, the absence of CELF1 reduced C/EBPβ levels and MuRF1 expression and was associated with decreased atrophy and histopathology in our mouse model, analogous to the results from the myoblast study. Furthermore, another group recently reported that C/EBPβ was expressed in satellite cells in skeletal muscle and that increased expression of C/EBPβ levels inhibited satellite cell and C2C12 myoblast differentiation and that loss of C/EBPβ in satellite cells promoted muscle differentiation (39). This may have relevance to DM1 muscle histopathology as it has been reported that satellite cell numbers were increased in muscles from DM1 patients without a concomitant increase in muscle regeneration, suggestive of a block in satellite cell activation or subsequent recruitment into a differentiation program (40). This is also consistent with reports of defects in differentiation and maturation in satellite cells from patients with DM1 (40,41).

In summary, CELF1 upregulation clearly correlates with severity of muscle pathology in DM1 patients and in our mouse model of RNA toxicity. However, our data suggest that even complete removal of CELF1 does not have a significant effect on key phenotypes of DM1 including myotonia, cardiac conduction defects and surprisingly, even several splicing defects. Thus, therapeutic approaches that target only CELF1 seem likely to have serious limitations, as Celf1−/− mice are small and weak and key DM1 phenotypes persist even in the absence of CELF1. However, reductions in CELF1 did have a beneficial effect on muscle histopathology and preservation of muscle function perhaps through alterations in the functions of CELF1 as a translational regulator. This suggests that targeting CELF1 could have limited therapeutic benefits with respect to the muscular dystrophy in DM1. But it is likely that this would have to be undertaken in a combinatorial approach with compounds that target MBNL1 sequestration, or the toxic RNA, or other novel pathways affected by RNA toxicity in patients with DM1.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mouse models

All animals were used in accordance with protocols approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Virginia. DM1 mouse models 5-313(background-FVB) were previously described (22). 5-313 mice were mated with Celf1−/− mice (background-C57BL/6N) (23) to generate Celf1−/−/5-313+/+. All progenies were genotyped by PCR. Six-week-old mice were induced with 0.2% of doxycycline in drinking water. 5-313+/− mice were used for the running and the grip-strength test. The remaining experiments used 5-313+/+ mice.

Human skeletal muscle samples

All skeletal muscle samples were from autopsy cases. Anonymous DM1 muscle samples (n = 8) were provided by Dr C. Thornton. Samples (with equal gender representation) were from either biceps or quadriceps femoris of patients with classic adult-onset DM1. Age range at death was from ∼45 to 55. The size of the (CTG) expansion was not available. Unaffected samples from adults were obtained from tissue banks and autopsy cases.

Protein isolation and western blot

Tissues were homogenized in RIPA buffer (50 mm Tris–HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mm NaCl, 1% NP-40, 0.5% Na–deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS) containing protease inhibitor and phosphatase inhibitor. Protein concentration was determined by Bradford assay with 20–40 μg of total protein per lane used for western blotting. Proteins were detected with the following antibodies: CELF1 (3B1, EMD Millipore), CELF2 (N-15, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), MBNL1 (A2764, gift of C.A. Thornton), MEF2 (C21, SCBT) and C/EBPβ (C-19, SCBT).

Treadmill assay and grip-strength test

Mice were examined for running endurance on a treadmill (Columbus Instruments, OH, USA). Mice were started for 1 min at 10 m/min and then ran at the speed of 15 m/min for 2 min. The treadmill accelerated to 29 m/min at a rate of 2 m/min/2 min. After 17 min, the treadmill was then increased to 30 m/min for 13 min. When the mice reached exhaustion (defined as greater than five consecutive seconds on the shock grid without attempting to re-engage the treadmill), they were removed from the device. Total time and total distance were recorded for each trial (Supplementary Material, Table S2).

Grip strength was measured using a digital grip-strength meter, which records the maximal strength an animal exerts while trying to resist an opposing pulling force (Columbus Instruments, Columbus, OH, USA). Forelimb grip strength was measured using a mouse tension bar. The results of five consecutive trials on the same day were averaged for each animal. Testers were blind to genotype.

ECGs and EMGs

ECG and EMG were measured as described previously (35,42). Mice were anesthetized with intraperitonial valium (2.5 mg/kg body weight) and ketamine (100 mg/kg body weight) and kept warm during the entire procedure. EMGs were carried out with a TD-20 MK1 EMG machine from TECA, using subdermal electrodes for stimulation, and grounding. Three-lead ECG was performed with a BioAmp/Powerlab from ADInstrument. All protocols were approved by and performed under the auspices of the UVA Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

RNA isolation and RT–PCR

Total RNA was extracted from skeletal muscle tissues using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg RNA using QuantiTech Reverse Transcription Kit (Qiagen) and then subjected to PCR using gene-specific primers. After separation on a 1% agarose gel or 10% acrylamide gel, bands were quantified using Kodak gel imaging and ImageQuant.

qRT–PCR was performed using the Bio-Rad iCycler and detected with SYBERGreen dye. Primer sequence and PCR conditions are given in Supplementary Material, Table S3. All assays were done in duplicate, and data normalization were accomplished using an endogenous control (Gapdh). The values were subjected to a  formula to calculate the fold change between the control and experimental groups.

formula to calculate the fold change between the control and experimental groups.

Histology

Skeletal muscles were collected in isopentane and frozen in liquid nitrogen. Tissues (quadriceps femoris) were cut at 6 μm with a cryostat. H&E staining was done according to standard procedures and examined under a light microscope.

Statistics

All data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Statistical significance was determined using a two-tailed Student’s t-test with equal or unequal variance as appropriate. Mann–Whitney U-test was used for non-parametric samples and χ2-test was used for multinomial samples. All statistical analyses were performed with Microsoft Excel and Minitap16 software. The significant level was set at P-values of <0.05 for all statistical analyses.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

Y.K.K., M.M., R.S.Y. and M.S.M. performed the experiments, L.P. provided the CELF1 deficient mice, and M.S.M. and Y.K.K. wrote the manuscript and designed the experiments.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

FUNDING

This work was funded by the Muscular Dystrophy Association (grant #114867) and the National Institutes of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (R01-AR045992). We thank the Stone Circle of Friends for their continued funding and support.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to Dr Charles Thornton for the patient tissues and we thank Jordan Gladman and Qing Yu for their insights, support and review of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brook J.D., McCurrach M.E., Harley H.G., Buckler A.J., Church D., Aburatani H., Hunter K., Stanton V.P., Thirion J.P., Hudson T., et al. Molecular basis of myotonic dystrophy: expansion of a trinucleotide (CTG) repeat at the 3′ end of a transcript encoding a protein kinase family member. Cell. 1992;69:385. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90418-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Day J.W., Ranum L.P. RNA Pathogenesis of the myotonic dystrophies. Neuromuscul. Disord. 2005;15:5–16. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2004.09.012. doi:10.1016/j.nmd.2004.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davis B.M., McCurrach M.E., Taneja K.L., Singer R.H., Housman D.E. Expansion of a CUG trinucleotide repeat in the 3′ untranslated region of myotonic dystrophy protein kinase transcripts results in nuclear retention of transcripts. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:7388–7393. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.14.7388. doi:10.1073/pnas.94.14.7388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taneja K.L., McCurrach M., Schalling M., Housman D., Singer R.H. Foci of trinucleotide repeat transcripts in nuclei of myotonic dystrophy cells and tissues. J. Cell. Biol. 1995;128:995–1002. doi: 10.1083/jcb.128.6.995. doi:10.1083/jcb.128.6.995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ladd A.N., Charlet N., Cooper T.A. The CELF family of RNA binding proteins is implicated in cell-specific and developmentally regulated alternative splicing. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2001;21:1285–1296. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.4.1285-1296.2001. doi:10.1128/MCB.21.4.1285-1296.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miller J.W., Urbinati C.R., Teng-Umnuay P., Stenberg M.G., Byrne B.J., Thornton C.A., Swanson M.S. Recruitment of human muscleblind proteins to (CUG)(n) expansions associated with myotonic dystrophy. EMBO J. 2000;19:4439–4448. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.17.4439. doi:10.1093/emboj/19.17.4439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fardaei M., Larkin K., Brook J.D., Hamshere M.G. In vivo co-localisation of MBNL protein with DMPK expanded-repeat transcripts. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:2766–2771. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.13.2766. doi:10.1093/nar/29.13.2766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Timchenko L.T., Miller J.W., Timchenko N.A., DeVore D.R., Datar K.V., Lin L., Roberts R., Caskey C.T., Swanson M.S. Identification of a (CUG)n triplet repeat RNA-binding protein and its expression in myotonic dystrophy. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:4407–4414. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.22.4407. doi:10.1093/nar/24.22.4407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mankodi A., Urbinati C.R., Yuan Q.P., Moxley R.T., Sansone V., Krym M., Henderson D., Schalling M., Swanson M.S., Thornton C.A. Muscleblind localizes to nuclear foci of aberrant RNA in myotonic dystrophy types 1 and 2. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2001;10:2165–2170. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.19.2165. doi:10.1093/hmg/10.19.2165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kanadia R.N., Johnstone K.A., Mankodi A., Lungu C., Thornton C.A., Esson D., Timmers A.M., Hauswirth W.W., Swanson M.S. A muscleblind knockout model for myotonic dystrophy. Science. 2003;302:1978–1980. doi: 10.1126/science.1088583. doi:10.1126/science.1088583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kanadia R.N., Shin J., Yuan Y., Beattie S.G., Wheeler T.M., Thornton C.A., Swanson M.S. Reversal of RNA missplicing and myotonia after muscleblind overexpression in a mouse poly(CUG) model for myotonic dystrophy. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:11748–11753. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604970103. doi:10.1073/pnas.0604970103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Han J., Cooper T.A. Identification of CELF splicing activation and repression domains in vivo. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:2769–2780. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki561. doi:10.1093/nar/gki561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kalsotra A., Xiao X., Ward A.J., Castle J.C., Johnson J.M., Burge C.B., Cooper T.A. A postnatal switch of CELF and MBNL proteins reprograms alternative splicing in the developing heart. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:20333–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809045105. doi:10.1073/pnas.0809045105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee J.E., Lee J.Y., Wilusz J., Tian B., Wilusz C.J. Systematic analysis of cis-elements in unstable mRNAs demonstrates that CUGBP1 is a key regulator of mRNA decay in muscle cells. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e11201. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011201. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0011201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Timchenko N.A., Wang G.L., Timchenko L.T. RNA CUG-binding protein 1 increases translation of 20-kDa isoform of CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein beta by interacting with the alpha and beta subunits of eukaryotic initiation translation factor 2. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:20549–20557. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409563200. doi:10.1074/jbc.M409563200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Timchenko L.T., Salisbury E., Wang G.L., Nguyen H., Albrecht J.H., Hershey J.W., Timchenko N.A. Age-specific CUGBP1-eIF2 complex increases translation of CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein beta in old liver. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:32806–32819. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605701200. doi:10.1074/jbc.M605701200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuyumcu-Martinez N.M., Wang G.S., Cooper T.A. Increased steady-state levels of CUGBP1 in myotonic dystrophy 1 are due to PKC-mediated hyperphosphorylation. Mol. Cell. 2007;28:68–78. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.07.027. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2007.07.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Timchenko N.A., Patel R., Iakova P., Cai Z.J., Quan L., Timchenko L.T. Overexpression of CUG triplet repeat-binding protein, CUGBP1, in mice inhibits myogenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:13129–13139. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312923200. doi:10.1074/jbc.M312923200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ho T.H., Bundman D., Armstrong D.L., Cooper T.A. Transgenic mice expressing CUG-BP1 reproduce splicing mis-regulation observed in myotonic dystrophy. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2005;14:1539–1547. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi162. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddi162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koshelev M., Sarma S., Price R.E., Wehrens X.H., Cooper T.A. Heart-specific overexpression of CUGBP1 reproduces functional and molecular abnormalities of myotonic dystrophy type 1. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2010;19:1066–1075. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp570. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddp570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ward A.J., Rimer M., Killian J.M., Dowling J.J., Cooper T.A. CUGBP1 Overexpression in mouse skeletal muscle reproduces features of myotonic dystrophy type 1. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2010;19:3614–3622. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq277. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddq277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mahadevan M.S., Yadava R.S., Yu Q., Balijepalli S., Frenzel-McCardell C.D., Bourne T.D., Phillips L.H. Reversible model of RNA toxicity and cardiac conduction defects in myotonic dystrophy. Nat. Genet. 2006;38:1066–1070. doi: 10.1038/ng1857. doi:10.1038/ng1857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kress C., Gautier-Courteille C., Osborne H.B., Babinet C., Paillard L. Inactivation of CUG-BP1/CELF1 causes growth, viability, and spermatogenesis defects in mice. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2007;27:1146–1157. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01009-06. doi:10.1128/MCB.01009-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Philips A.V., Timchenko L.T., Cooper T.A. Disruption of splicing regulated by a CUG-binding protein in myotonic dystrophy. Science. 1998;280:737–741. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5364.737. doi:10.1126/science.280.5364.737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Savkur R.S., Philips A.V., Cooper T.A. Aberrant regulation of insulin receptor alternative splicing is associated with insulin resistance in myotonic dystrophy. Nat. Genet. 2001;29:40–47. doi: 10.1038/ng704. doi:10.1038/ng704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Charlet B.N., Savkur R.S., Singh G., Philips A.V., Grice E.A., Cooper T.A. Loss of the muscle-specific chloride channel in type 1 myotonic dystrophy due to misregulated alternative splicing. Mol. Cell. 2002;10:45–53. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00572-5. doi:10.1016/S1097-2765(02)00572-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bland C.S., Wang E.T., Vu A., David M.P., Castle J.C., Johnson J.M., Burge C.B., Cooper T.A. Global regulation of alternative splicing during myogenic differentiation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:7651–7664. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq614. doi:10.1093/nar/gkq614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mankodi A., Takahashi M.P., Jiang H., Beck C.L., Bowers W.J., Moxley R.T., Cannon S.C., Thornton C.A. Expanded CUG repeats trigger aberrant splicing of ClC-1 chloride channel pre-mRNA and hyperexcitability of skeletal muscle in myotonic dystrophy. Mol. Cell. 2002;10:35–44. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00563-4. doi:10.1016/S1097-2765(02)00563-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kino Y., Washizu C., Oma Y., Onishi H., Nezu Y., Sasagawa N., Nukina N., Ishiura S. MBNL and CELF proteins regulate alternative splicing of the skeletal muscle chloride channel CLCN1. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:6477–6490. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp681. doi:10.1093/nar/gkp681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ho T.H., Charlet B.N., Poulos M.G., Singh G., Swanson M.S., Cooper T.A. Muscleblind proteins regulate alternative splicing. EMBO J. 2004;23:3103–3112. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600300. doi:10.1038/sj.emboj.7600300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Du H., Cline M.S., Osborne R.J., Tuttle D.L., Clark T.A., Donohue J.P., Hall M.P., Shiue L., Swanson M.S., Thornton C.A., et al. Aberrant alternative splicing and extracellular matrix gene expression in mouse models of myotonic dystrophy. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2010;17:187–193. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1720. doi:10.1038/nsmb.1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin X., Miller J.W., Mankodi A., Kanadia R.N., Yuan Y., Moxley R.T., Swanson M.S., Thornton C.A. Failure of MBNL1-dependent post-natal splicing transitions in myotonic dystrophy. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2006;15:2087–2097. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl132. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddl132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Berger D.S., Moyer M., Kliment G.M., van Lunteren E., Ladd A.N. Expression of a dominant negative CELF protein in vivo leads to altered muscle organization, fiber size, and subtype. PLoS ONE. 2010;6:e19274. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019274. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0019274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Berger D.S., Ladd A.N. Repression of nuclear CELF activity can rescue CELF-regulated alternative splicing defects in skeletal muscle models of myotonic dystrophy. PLoS Curr. 4:RRN1305. doi: 10.1371/currents.RRN1305. doi:10.1371/currents.RRN1305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yadava R.S., Frenzel-McCardell C.D., Yu Q., Srinivasan V., Tucker A.L., Puymirat J., Thornton C.A., Prall O.W., Harvey R.P., Mahadevan M.S. RNA Toxicity in myotonic muscular dystrophy induces NKX2–5 expression. Nat. Genet. 2008;40:61–68. doi: 10.1038/ng.2007.28. doi:10.1038/ng.2007.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gonnella P., Alamdari N., Tizio S., Aversa Z., Petkova V., Hasselgren P.O. C/EBPbeta regulates dexamethasone-induced muscle cell atrophy and expression of atrogin-1 and MuRF1. J. Cell. Biochem. 2010;112:1737–1748. doi: 10.1002/jcb.23093. doi:10.1002/jcb.23093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang G.S., Kearney D.L., De Biasi M., Taffet G., Cooper T.A. Elevation of RNA-binding protein CUGBP1 is an early event in an inducible heart-specific mouse model of myotonic dystrophy. J. Clin. Invest. 2007;117:2802–2811. doi: 10.1172/JCI32308. doi:10.1172/JCI32308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Timchenko N.A., Cai Z.J., Welm A.L., Reddy S., Ashizawa T., Timchenko L.T. RNA CUG repeats sequester CUGBP1 and alter protein levels and activity of CUGBP1. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:7820–7826. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005960200. doi:10.1074/jbc.M005960200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marchildon F., Lala N., Li G., St-Louis C., Lamothe D., Keller C., Wiper-Bergeron N. CCAAT/Enhancer binding protein beta is expressed in satellite cells and controls myogenesis. Stem Cells. 2010;30:2619–2630. doi: 10.1002/stem.1248. doi:10.1002/stem.1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thornell L.E., Lindstom M., Renault V., Klein A., Mouly V., Ansved T., Butler-Browne G., Furling D. Satellite cell dysfunction contributes to the progressive muscle atrophy in myotonic dystrophy type 1. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 2009;35:603–613. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2009.01014.x. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2990.2009.01014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Furling D., Coiffier L., Mouly V., Barbet J.P., St Guily J.L., Taneja K., Gourdon G., Junien C., Butler-Browne G.S. Defective satellite cells in congenital myotonic dystrophy. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2001;10:2079–2087. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.19.2079. doi:10.1093/hmg/10.19.2079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wheeler T.M., Lueck J.D., Swanson M.S., Dirksen R.T., Thornton C.A. Correction of ClC-1 splicing eliminates chloride channelopathy and myotonia in mouse models of myotonic dystrophy. J. Clin. Invest. 2007;117:3952–3957. doi: 10.1172/JCI33355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.