Abstract

Objective

Taekwondo injuries differ according to the characteristics of the athletes and the competition. This analytical cross-sectional retrospective cohort study aimed to describe reported taekwondo injuries and to determine the prevalence, characteristics and possible risk factors for injuries sustained by athletes of the Spanish national team. In addition, we compared each identified risk factor—age, weight category, annual quarter, injury timing and competition difficulty level—with its relation to injury location and type.

Settings

Injury occurrences in taekwondo athletes of the Spanish national team during two Olympic periods at the High Performance Centre in Barcelona were analysed.

Participants

48 taekwondo athletes (22 male, 26 female; age range 15–31 years) were studied; 1678 injury episodes occurred. Inclusion criteria were: (1) having trained with the national taekwondo group for a minimum of one sports season; (2) being a member of the Spanish national team.

Results

Independently of sex or Olympic period, the anatomical sites with most injury episodes were knee (21.3%), foot (17.0%), ankle (12.2%), thigh (11.4%) and lower leg (8.8%). Contusions (29.3%) and cartilage (17.6%) and joint (15.7%) injuries were the prevalent types of injury. Chronological age, weight category and annual quarter can be considered risk factors for sustaining injuries in male and female elite taekwondists according to their location and type (p≤0.001).

Conclusions

This study provides epidemiological information that will help to inform future injury surveillance studies and the development of prevention strategies and recommendations to reduce the number of injuries in taekwondo competition.

Keywords: Sports Medicine, Rehabilitation Medicine

Strengths and limitations of this study.

A large analytical cross-sectional study over an 8-year period and the new findings of different associations between risk factors for injury, and its location and type, in elite taekwondo athletes are among the main strengths.

The retrospective nature and unavailability of some relevant data are limitations.

Prevention strategies and recommendations to reduce the number of injuries in taekwondo should be proposed after analysing the data provided.

Introduction

Taekwondo is an ancient systematic and scientific Korean martial art that involves multiple physical fighting skills. This fully recognised Olympic sport is regulated by the World Taekwondo Federation and is one of the most popular sports worldwide, with 75–120 million practitioners in more than 140 countries. Spain was at the top of the medals ranking table in the London 2012 Olympic Games and traditionally has great international sporting success.1

Taekwondo competitive performance depends on several factors including physical,2–6 psychological,7 8 technical9 10 and tactical.11–13 Practitioners compete according to sex and defined weight category classifications in a full-contact event between two opponents divided into three semi-continuous rounds of 2 min, with 1 min’s rest between rounds. Taekwondists are equipped with a padded trunk protector, protective padded headgear, protective gloves and shin guards. Victory is achieved by higher scores given by judges for the specific fighting techniques allowed (kicks and punches), accurately and powerfully, in the legal scoring areas (the abdomen, both sides of the flank and the permitted parts of the face).

Understanding the injury pattern of a particular sport and its inherent risk factors is a key area of current sports medicine.14 As in many other combat sports, there is high potential for injury associated with elite athletic performance in taekwondo.15–21 Defining injury as any circumstance for which the athlete sought the assistance of on-site medical personnel, the latest reviews on competition injuries in taekwondo concluded that total injury rates are 20.6–139.5 per 1000 athlete-exposure (A-E) for elite men and 25.3–105.5 per 1000 A-E for elite women. When only time-loss injuries are considered, rates are 6.9–33.6 per 1000 A-E for men and 2.4–23.0 per 1000 A-E for women.20

The main injury mechanism in taekwondo is through direct contact, especially the exchange of accurate turning kicks and poorly performed or non-existent blocking skills.17 20 22 23 The vast majority of all injuries are localised to the lower extremities, especially the instep of the foot, and these are contusions, sprains and muscle strains.17 20 24 25 The head and neck regions are the next most likely to receive taekwondo competition injuries.17 20

Despite the well-documented epidemiology injury profile in taekwondo competition, relatively few studies have evaluated the incidence of injury risk factors related to the training process and long-term preparation in elite level athletes. The main objective of this 8-year cross-sectional retrospective cohort study was to determine the prevalence, characteristics (anatomical location and injury type) and possible injury risk factors in male and female Spanish national team (SNT) taekwondists trained at the High Performance Sports Centre (CAR) in Sant Cugat del Vallés (Barcelona, Spain) throughout two different Olympic periods (OPs) (Sydney (1997–2000) and Athens (2001–2004)).

Methods

Type of study

This study is a large analytical cross-sectional retrospective cohort study over 8 years, divided into two different 4-year OPs.

Study participants

From 1 January 1997 to 31 December 2004, 48 taekwondo athletes from the SNT were studied. There were 22 male and 26 female athletes (45.8% and 54.2% of all athletes, respectively). The mean ± SD age of the athletes in this study was 21.6±1.2 years (minimum 15 years, maximum 31 years). Inclusion criteria were: (1) trained with the national taekwondo group for a minimum of one sports season; (2) being a member of the SNT.

Data collection and injury report form

Two data sources were used: (1) a comprehensive database obtained from the CAR to provide personal and general information about each athlete; (2) an electronic medical data capture system from the CAR medical department. This contained the following data fields in an unidentified format: athlete accreditation number, sex, age, date of first registration at CAR, weight category, medical visit date (day/month/year) and injury diagnosis. All injuries were diagnosed by sports medicine doctors, and subsequently recorded by anatomical location (OSICS-1) and injury type (OSICS-2) according to the Orchard Sports Injury Classification System, V.10 (OSICS-10).26 The system of data entry and storage complied with existing European Union standards for medical data storage.27

Procedures

The total number of injury episodes (IEs) (n=1678; male, n=912; female, n=766) were obtained and analysed individually for every elite taekwondist classified by sex and OP. The definition of IE corresponds to the series of medical visits (MVs) by an athlete, related to the same injury (same OSICS coding) and occurring no more than 2 months apart. If the time between MVs was greater than 2 months, this was classified as a new episode. We determined this length of time according to the definition of reinjury proposed by Hagglund et al:28 ‘an injury of the same type and location of a previous injury that occurred within 2 months of the final rehabilitation day of the previous injury’. In addition, a severity index of injury was included based on the number of MVs generated by an IE (the more MVs, the greater the severity). Results related to MVs are shown in the online supplementary data.

Analysed variables used were: chronological age (expressed in years and three age groups: 15–20 years, 21–25 years and 26–31 years); weight category (very light, light, medium and heavy); annual quarter when injury occurred; injury timing (pre-competition (15 days before the beginning of the competition); competition and/or post-competition (all the injuries sustained in competition and/or up to15 days after the last day of competition); out of competition or during training sessions); competition difficulty level (World Championships (WC), World Cups (WCU), European Championships (EUC), National Championships (NC)), which includes as pre-competition injuries all the injuries registered during 15 days before the first day of competition and as post-competition injuries all the injuries registered during the days of competition and/or up to 15 days after the last day of competition.

Definition of injury

This study adhered to the operational injury definition recommended by Junge et al14: a new or recurring musculoskeletal complaint or concussion incurred during competition or training receiving medical attention, regardless of time loss from competition or training.

Confidentiality and ethics approval

Research ethics approval was obtained from the Ethics Sports Clinical Investigations Committee of Catalonia (ID-0099S/10308/2011). Informed consent was obtained from the subjects to access and collect their medical history data and to voluntarily participate in the study. All data were stored on highly secured, password-protected files. The investigators signed a confidentiality agreement that states all data gathered during the duration of the study will be used solely for the purpose of the investigation.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as the number of IEs and presented as the standard basic descriptive statistics of mean and SD. Injury classification (OSICS-1, anatomical location; OSICS-2, injury type) and independent variables (age, weight category, annual quarter, injury timing, competition difficulty level) were analysed in relation to sex and OP. To compare the differences between the two OPs or between sexes, we performed a Student's t test or analogue non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test, depending on whether or not, respectively, the data were normally distributed. To analyse the probability of considering a risk factor or a possible behaviour-dependent generator between the injuries (by the criterion of OSICS classification) and each of the independent variables, we used the Pearson χ2 test and adjusted OR. We regarded two-tailed p Bonferroni-adjusted values ≤0.001 as significant. All statistical modelling was performed using SPSS V.19.0.

Results

OSICS-1 classification (anatomical sites)

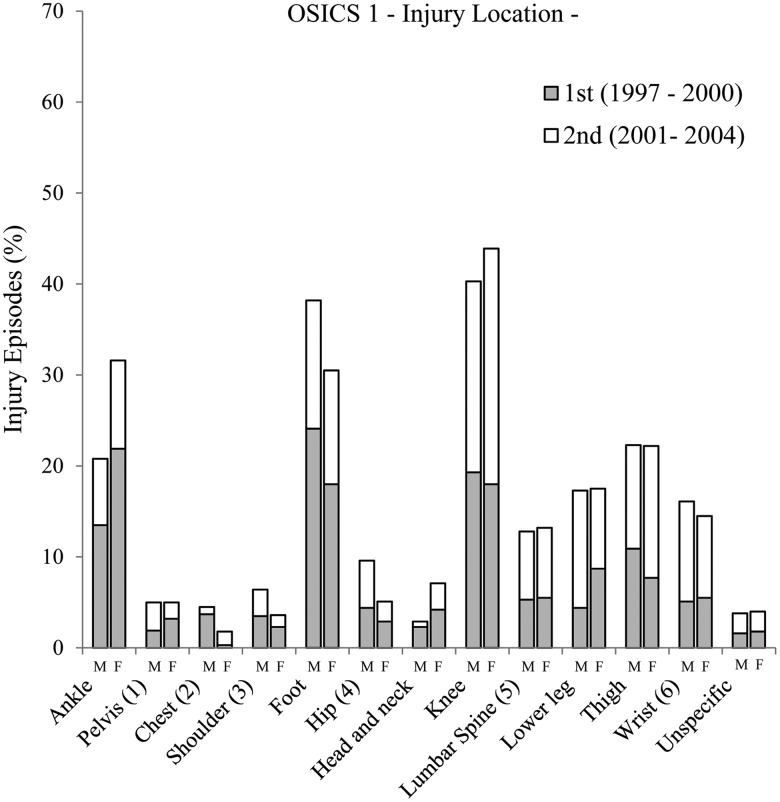

Independently of sex or OP, the anatomical sites with most IEs were knee, foot, ankle, thigh and lower leg (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Location of injury episode according to two Olympic periods (1997–2000 and 2001–2004) and sex (M, male; F, female) of the athletes. 1, Pelvis and buttock; 2, chest, trunk, abdomen and thoracic spine; 3, shoulder, upper arm, elbow, forearm; 4, hip and groin; 5, lumbar spine; 6, wrist and hand.

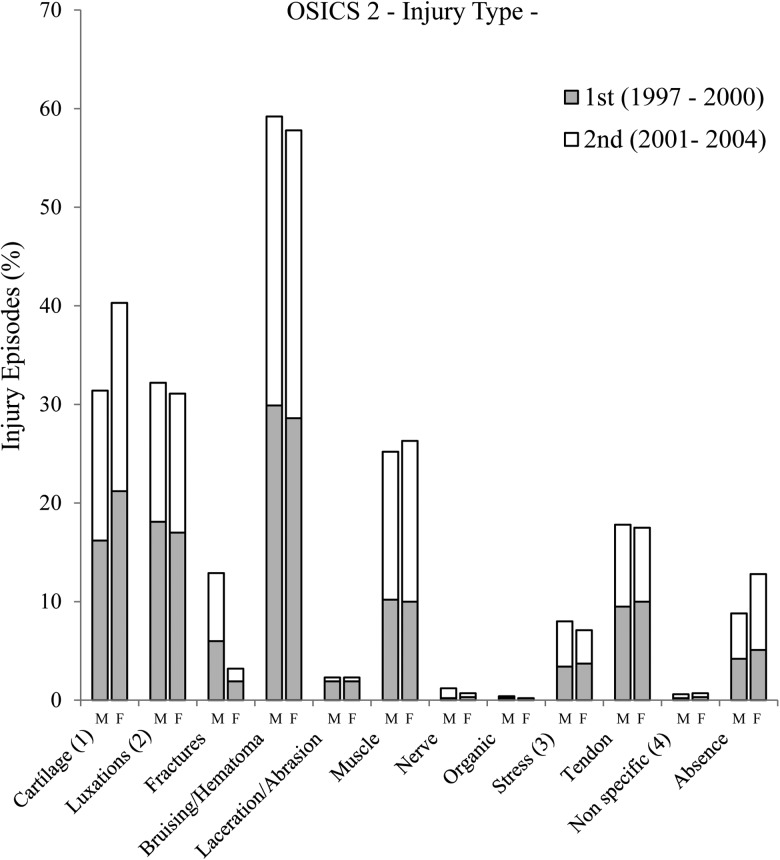

OSICS-2 classification (injury type)

Independently of sex or OP, the types of injury in most IEs were: bruising/haematomas (contusions); joint dislocations and joint sprains; arthritis, cartilage injuries, synovitis, impingements, bursitis and chronic instability; muscle injuries; tendon injuries (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Injury type according to two Olympic periods (1997–2000 and 2001–2004) and sex (M, male; F, female) of the athletes. 1, Arthritis, cartilage injuries, synovitis, impingements, bursitis and chronic instability; 2, joint dislocations and joint sprains; 3, stress fractures, other stress and overuse injuries; 4, whiplash and non-specific injuries.

Chronological age

A significant difference in IEs was found between sexes during the first OP in the age group 21–25 years (male, 48.8±11.9; female, 26.6±6.7; p=0.03). Independently of OP, the age group in which the greatest number of IEs was recorded was 23–24 years for male athletes (n=187; 20.5%) and 17–18 years for female athletes (n=174; 22.7%) (table 1). With the data values provided (table 2), exclusively during the second OP, there seems to exist a sufficiently high injury prevalence in anatomical locations (OSICS-1) or injury types (OSICS-2), as for consider a behaviour susceptible to be dependent (male, OR=2.62; female, OR=3.07).

Table 1.

Injury episodes according to chronological age group, related to sex and Olympic period

| Age (years) | Male | Female | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | 2nd | 1st | 2nd | |||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| 15 | 3 | 0.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 11 | 3.5 | 4 | 0.9 |

| 16 | 23 | 5.3 | 2 | 0.4 | 38 | 12.2 | 22 | 4.8 |

| 17 | 25 | 5.8 | 22 | 4.6 | 58 | 18.6 | 30 | 6.6 |

| 18 | 23 | 5.3 | 38 | 7.9 | 30 | 9.6 | 56 | 12.3 |

| 19 | 31 | 7.2 | 53 | 11.0 | 17 | 5.5 | 44 | 9.7 |

| 20 | 43 | 10.0 | 49 | 10.2 | 4 | 1.3 | 62 | 13.6 |

| 21 | 57 | 13.2 | 37 | 7.6 | 18 | 5.8 | 53 | 11.6 |

| 22 | 42 | 9.7 | 24 | 5.0 | 26 | 8.4 | 42 | 9.3 |

| 23 | 65 | 15.1 | 41 | 8.5 | 35 | 11.3 | 43 | 9.5 |

| 24 | 44 | 10.2 | 37 | 7.7 | 31 | 10.0 | 28 | 6.2 |

| 25 | 36 | 8.4 | 50 | 10.4 | 23 | 7.4 | 13 | 2.9 |

| 26 | 14 | 3.2 | 59 | 12.3 | 10 | 3.2 | 16 | 3.5 |

| 27 | 17 | 3.9 | 37 | 7.7 | 10 | 3.2 | 22 | 4.8 |

| 28 | 6 | 1.4 | 11 | 2.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 11 | 2.4 |

| 29 | 2 | 0.5 | 9 | 1.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 7 | 1.5 |

| 30 | 0 | 0.0 | 12 | 2.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| 31 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 0.4 |

n, number of injury episodes; 1st, 1997–2000; 2nd, 2001–2004.

Table 2.

Statistical dependency levels of independent variables according to sex and two different Olympic periods

| Variable | Sex | OSICS | Olympic period | IE (n) | df | χ2 | padjusted | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chronological age | Male | 1 | 1st | 431 | 24 | 43.04 | 0.005 | |

| 2 | 22 | 40.99 | 0.005 | |||||

| 1 | 2nd | 481 | 24 | 48.71 | 0.001* | |||

| 2 | 22 | 49.81 | 0.001* | |||||

| Female | 1 | 1st | 311 | 24 | 128.63 | 0.002 | ||

| 2 | 22 | 44.26 | 0.003 | |||||

| 1 | 2nd | 455 | 24 | 114.98 | 0.001* | |||

| 2 | 22 | 78.56 | 0.001* | |||||

| Weight category | Male | 1 | 1st | 431 | 36 | 131.56 | 0.001* | |

| 2 | 33 | 53.38 | 0.005 | |||||

| 1 | 2nd | 481 | 36 | 348.18 | 0.001* | |||

| 2 | 33 | 188.11 | 0.001* | |||||

| Female | 1 | 1st | 311 | 36 | 140.39 | 0.001* | ||

| 2 | 33 | 86.83 | 0.001* | |||||

| 1 | 2nd | 455 | 36 | 170.15 | 0.001* | |||

| 2 | 33 | 128.78 | 0.001* | |||||

| Annual quarter | Male | 1 | 1st | 431 | 36 | 34.57 | 0.500 | |

| 2 | 33 | 27.50 | 0.700 | |||||

| 1 | 2nd | 481 | 36 | 245.14 | 0.001* | |||

| 2 | 33 | 110.42 | 0.001* | |||||

| Female | 1 | 1st | 311 | 36 | 114.17 | 0.001* | ||

| 2 | 33 | 72.07 | 0.001* | |||||

| 1 | 2nd | 455 | 36 | 83.60 | 0.001* | |||

| 2 | 33 | 72.89 | 0.001* | |||||

| Injury timing | Male | 1 | 1st | 431 | 24 | 29.59 | 0.150 | |

| 2 | 22 | 19.09 | 0.600 | |||||

| 1 | 2nd | 481 | 24 | 19.13 | 0.700 | |||

| 2 | 22 | 25.75 | 0.250 | |||||

| Female | 1 | 1st | 311 | 24 | 82.50 | 0.002 | ||

| 2 | 22 | 33.43 | 0.050 | |||||

| 1 | 2nd | 455 | 24 | 131.80 | 0.002 | |||

| 2 | 22 | 69.65 | 0.010 | |||||

| Competition difficulty level | Male | Pre | 1 | 1st | 102 | 36 | 41.56 | 0.200 |

| 2 | 33 | 22.01 | 0.900 | |||||

| 1 | 2nd | 106 | 36 | 44.7 | 0.100 | |||

| 2 | 33 | 27.41 | 0.700 | |||||

| Post | 1 | 1st | 82 | 36 | 27.82 | 0.850 | ||

| 2 | 33 | 24.29 | 0.850 | |||||

| 1 | 2nd | 76 | 36 | 28.80 | 0.750 | |||

| 2 | 33 | 33.76 | 0.400 | |||||

| Female | Pre | 1 | 1st | 86 | 36 | 40.83 | 0.250 | |

| 2 | 33 | 40.27 | 0.150 | |||||

| 1 | 2nd | 97 | 36 | 42.67 | 0.200 | |||

| 2 | 33 | 12.53 | 0.990 | |||||

| Post | 1 | 1st | 40 | 36 | 15.46 | 0.990 | ||

| 2 | 33 | 17.98 | 0.975 | |||||

| 1 | 2nd | 63 | 36 | 22.37 | 0.950 | |||

| 2 | 33 | 19.62 | 0.950 |

OSICS: 1, injury location; 2, injury type.

Pre: 1st, 1997–2000; 2nd, 2001–2004.

*padjusted: significance level ≤0.001.

df, degrees of freedom; IE, injury episode; n, number of injury episodes.

Weight category

Independently of the OP analysed, the male weight category group with the most IEs was <58 kg (35.6%; n=325), followed by 58–68 kg (30.9%; n=282), 68–80 kg (17.6%; n=160) and >80 kg (15.9%; n=145). For female athletes, the light weight category (49–57 kg) had the most IEs (30.9%; n=237), followed by the 57–67 kg (30.2%; n=231), <49 kg (29.9%; n=229) and >67 kg (9.0%; n=69) categories. Significant differences (p=0.01) were found between sexes in all weight categories (in the very light and heavy weight categories during the first OP, and in the light and medium weight category during the second OP) and between OPs for the same sex: female athletes in very light and heavy weight categories and male athletes in light and medium weight categories. Excluding the first OP, OSICS-2 for male athletes (table 2) there seems to be a sufficiently high injury prevalence in anatomical locations (OSICS-1) or injury types (OSICS-2) to consider the weight category an injury risk factor (male, OR=2.02; female, OR=1.50).

Annual quarter

Of the 912 IEs in male athletes (table 3), 35.7% (n=326) were sustained in the first annual quarter, 26.3% (n=240) in the second quarter, 15.3% (n=139) in the third quarter, and 22.7% (n=207) in the fourth quarter. Of the 766 IEs in female athletes (table 3), 33.0% (n=253) were sustained in the first quarter, 31.1% (n=238) in the second quarter, 14.5% (n=111) in the third quarter, and 21.4% (n=164) in the fourth quarter.

Table 3.

Injury episodes according to the month when injury occurred, related to sex and Olympic period

| Month | Male | Female | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | 2nd | 1st | 2nd | |||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| January | 43 | 10.0 | 47 | 9.8 | 47 | 15.1 | 51 | 11.2 |

| February | 55 | 12.8 | 72 | 15.0 | 26 | 8.4 | 47 | 10.3 |

| March | 59 | 13.7 | 50 | 10.4 | 35 | 11.3 | 47 | 10.3 |

| April | 42 | 9.7 | 50 | 10.4 | 40 | 12.9 | 53 | 11.6 |

| May | 52 | 12.1 | 54 | 11.2 | 48 | 15.4 | 64 | 14.1 |

| June | 29 | 6.7 | 13 | 2.7 | 13 | 4.2 | 20 | 4.4 |

| July | 7 | 1.6 | 30 | 6.2 | 4 | 1.3 | 8 | 1.8 |

| August | 18 | 4.2 | 13 | 2.7 | 24 | 7.7 | 23 | 5.2 |

| September | 31 | 7.2 | 40 | 8.3 | 20 | 6.4 | 32 | 7.0 |

| October | 39 | 9.0 | 31 | 6.4 | 28 | 9.0 | 36 | 7.9 |

| November | 42 | 9.7 | 63 | 13.1 | 15 | 4.8 | 48 | 10.5 |

| December | 14 | 3.3 | 18 | 3.8 | 11 | 3.5 | 26 | 5.7 |

n, number of injury episodes; 1st, 1997–2000; 2nd, 2001–2004.

No differences were found between sexes or OP. Excluding the results for male taekwondists during the first OP (table 2), the annual quarter seems to show a significant prevalence of injury anatomical site (OSICS-1) and injury type (OSICS-2), and could be considered an injury risk factor (male athletes, OR=2.04; female athletes, OR=1.71).

Injury timing

Of the total of 1678 IEs, 61.1% (n=1026) were sustained during training sessions or out of competition, 23.3% (n=391) in the pre-competition period, and 15.6% (n=261) in competition or the post-competition period. No differences were found between the OPs according to the number of IEs. There was no significant relationship between injury timing and injury anatomical site (OSICS-1) or injury type (OSICS-2). Therefore, from the numbers available, injury timing cannot be considered a risk factor or possible behaviour-dependent generator of injuries in elite taekwondo athletes (table 2).

Competition difficulty level

Of the 367 IEs in competition in male athletes, 45.2% (n=166) were sustained during NC, 14.4% (n=53) during EUC, 27.2% (n=100) during WC, and 13.1% (n=48) during WCU. Of the 286 IEs in competition in female athletes, 38.8% (n=111) were sustained during NC, 17.5% (n=50) during EUC, 25.5% (n=73) during WC, and 18.2% (n=52) during WCU. No differences were found between OPs according to the number of IEs in relation to the competition difficulty level. There was no significant relationship between competition difficulty level and injury anatomical site (OSICS-1) or injury type (OSICS-2). These results are independent of whether the injury occurred before or after competition (table 2). So, from the current data, the competition difficulty level cannot be considered a risk factor or a possible behaviour-dependent generator of injuries in elite taekwondo athletes.

Discussion

This study examined the effect of age, weight category, annual quarter, injury timing, and competition difficulty level on injury location and type in elite taekwondo athletes. The anatomical sites with the greatest injury incidence were the lower limbs (knee, foot, ankle, thigh and lower leg) for both male and female athletes. These anatomical locations are related to different injury types, prevailing contusions, joint and cartilage injuries and, in smaller proportions, to tendon and muscle injuries. Age, weight category and annual quarter show a statistically significant relation as possible injury risk factors in elite taekwondo. In contrast, injury timing and competition difficulty level do not seem to have any relationship to the injury prevalence in this combat sport.

The study has some limitations which should be considered. First, and perhaps most importantly, it does not have a prospective and/or longitudinal design (it was not possible, eg, to determine exactly when the injury occurred or to calculate injury rates with adequate accuracy, or to obtain previous injury information or a training load indicator). Second, despite the high number of IEs, a low number of elite taekwondists was included, which may have resulted in a relevant bias.

Injury location (OSICS-1) and injury type (OSICS-2)

Spanish male taekwondists sustained a higher number of IEs than their female equivalents; however, no statistically significant difference was found. Other studies have reported similar findings.29–35 Previous research cites the most common injury location as the lower limb.17 24 31 32 34 36–39 This is not surprising because of the use of the lower limb as the primary striking weapon. There are no significance differences between sexes in knee injuries, which is a surprising finding because, according to many research papers, being female is a risk factor for more knee injuries.40–42 It is possible that this risk factor is minimised because the two sexes train similarly and follow the same prevention programmes, which is uncommon in other sports. The foot is the second location with a high number of IEs, which is not surprising as the majority of kicking techniques use the foot. It has been confirmed that 98 out of 100 hundred kicking techniques are executed with the foot.43 44 The chest, thoracic column and abdomen are the locations with the least IEs, which may be related to the use of protection in these zones during training sessions and competitions. The prevalence of contusions and joint and cartilage injuries is in accordance with related literature.26 30 This is logical because practitioners are constantly kicking each other.

Risk factors (dependent variables)

The highest injury prevalence occurs at different ages according to sex: 23–24 years in male athletes; 17–18 years in female athletes. Many related studies have found a significant correlation between age and injury incidence.16 22 24 35–37 The data from this study confirm these results, indicating age as a potential risk factor for injury incidence in elite taekwondo athletes.

Sex difference according to weight category is a clear indicator that men suffer more injuries in all weight categories with the exception of the intermediate weight category. This exception can be explained by the fact that there are fewer male taekwondo athletes represented in this category. Moreover, the weight category emerges as a possible injury risk factor.

All sports training systems vary depending on the competitive calendar and consequently on the season. In this study, this seems to affect the injury pattern of taekwondo athletes and can be considered a risk factor by coaches and sports medicine specialists.

Finally, of the variables that can be considered risk factors, some differences according to sex and/or OP were recorded. The first OP, with regard to age (male and female, and OSICS-1 and OSICS-2), weight category (male and OSICS-2) and, in particular, annual period (male, and OSICS-1 and OSICS-2), seems to show different behaviour as an injury risk factor. Although, because of the retrospective nature of this study, the training load was not recorded, it is known that the Spanish coaches in charge were different during the two OPs analysed. Different training systems, applied in a certain way for both sexes, may be one of the reasons for these results. Therefore, each sporting context should be analysed specifically in order to assess the full dimension of the elite injury epidemiology in taekwondo.

Conclusions

The anatomical sites with most injury incidence are the knee, foot, ankle, thigh and lower leg. In SNT, the most prevalent injuries are contusions and joint and cartilage injuries. Chronological age, weight category, and annual quarter show a statistically significant relation as possible injury risk factors according to sex or different OP. This study has some limitations: it is not a prospective and/or longitudinal design and, despite the high number of IEs, the number of elite taekwondists included is small. The study provides epidemiological information that will help to inform future injury surveillance studies. Further research is needed to achieve a better understanding of elite taekwondo, in relation to sex and different training systems.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the athletes who participated in the study, as well as to the technical staff and medical department of the National Taekwondo Federation.

Footnotes

Contributors: All the authors contributed in a substantial manner to the planning and conduct of the testing, literature review and/or manuscript preparation. Conceived and designed: AAB, FD, AI. Analysed the data: AAB, JBM, AI. Contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools: AAB, LT, JBM, AI. Wrote the paper: AAB, FD, NM, AI. All gave final approval of the version submitted.

Funding: The study was supported by grants from the Agency for Management of University and Research Grants (AGAUR) the Catalan National Institute of Physical Education (Institut Nacional d'Educació Física de Catalunya) and the High Performance Centre (Centre Alt Rendiment Esportiu), Generalitat de Catalunya; resolution : VCP/3346/2009.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Sports Clinical Investigations Committee of Catalonia.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Extra data are available by emailing AAB.

References

- 1.World-Taekwondo-Federation. http://www.wtf.org/wtf_eng/main/main_eng.html (accessed 29 Apr 2013)

- 2.Heller J, Peric T, Dlouha R, et al. Physiological profiles of male and female taekwondo (ITF) black belts. J Sports Sci 1998;16:243–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gao B. Research on the somatotype features of chinese elite male taekwondo athletes. Sport Sci 2001;21:58–61 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Melhim A. Aerobic and anaerobic power responses to the practice of taekwondo. Br J Sports Med 2001;35:231–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ball N, Nolan E, Wheeler K. Anthropometrical, physiological, and tracked power profiles of elite taekwondo athletes 9 weeks before the olympic competition phase. J Strength Cond Res 2011;25:2752–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Estevan I, Alvarez O, Falco C, et al. Impact force and time analysis influenced by execution distance in a roundhouse kick to the head in taekwondo. J Strength Cond Res 2011;25:2851–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grosser M, Brüggemann P, Zintl F. Alto rendimiento: planificación y desarrollo. Madrid: Martínez Roca, 1989 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gónzalez de Prado C. Caracterización técnico-táctica de la competición de combate de alto nivel en taekwondo. efectividad de las acciones tácticas [dissertation]. Barcelona: Universitat de Barcelona, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bridge CA, Jones MA, Drust B. The activity profile in international taekwondo competition is modulated by weight category. Int J Sports Physiol Perform 2011;6:344–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cular D, Krstulovic S, Tomljanovic M. The differences between medalists and non medalists at the 2008 Olympic Games taekwondo tournament. Hum Mov 2011;12:165–70 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hardy L, Jones G, Gould D, eds. Understanding psychological preparation for sport. New York: John Wiley and Sons, 1996 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Falcó C, Alvarez O, Castillo I, et al. Influence of the distance in a roundhouse kick's execution time and impact force in taekwondo. J Biomech 2009;42:242–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.González de Prado C, Iglesias X, Mirallas J, et al. Sistematización de la acción táctica en el taekwondo de alta competición. Apunts. Educación Física y Deportes 2011;103:56–67 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Junge A, Engebretsen L, Alonso JM, et al. Injury surveillance in multi-sport events: The international olympic committee approach. Br J Sports Med 2008;42:413–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feehan M, Waller AE. Precompetition injury and subsequent tournament performance in full-contact taekwondo. Br J Sports Med 1995;29:258–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beis K, Tsaklis P, Pieter W, et al. Taekwondo competition injuries in Greek young and adult athletes. Eur J Sports Traumatol Relat Res 2001;23:130–6 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lystad RP, Pollard H, Graham PL. Epidemiology of injuries in competition taekwondo: a meta-analysis of observational studies. J Sci Med Sport 2009;12:614–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schluter-Brust K, Leistenschneider P, Dargel J, et al. Acute injuries in taekwondo. Int J Sports Med 2011;32:629–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kazemi M. Relationships between injury and success in elite taekwondo athletes. J Sports Sci 2012;30:277–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pieter W, Fife GP, O'Sullivan DM. Competition injuries in taekwondo: A literature review and suggestions for prevention and surveillance. Br J Sports Med 2012;46:485–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Engebretsen L, Soligard T, Steffen K, et al. Sports injuries and illnesses during the London Summer Olympic Games 2012. Br J Sports Med 2013;47:407–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pieter W, Zemper ED. Head and neck injuries in young taekwondo athletes. J Sports Med Phys Fitness 1999b;39:147–53 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zetou E. Injuries in taekwondo athletes. Physical Training. http://ejmas.com/pt/2006pt/ptart_Zetou_0906.html (accessed 30 May 2013)

- 24.Kazemi M, Shearer H, Choung YS. Pre-competition habits and injuries in taekwondo athletes. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2005;6:26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pieter W. Taekwondo. In: Kordi R, Mafulli N, Wroble RR, Wallace WA, eds. Combat sports medicine. London: Springer, 2009:263–86 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Til L, Orchard J, Rae K. El sistema de classificació i codificació OSICS-10 traduït de l'anglès. Apunts Medicina De L'Esport 2008;43:109 [Google Scholar]

- 27. Directive 95/46/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 24 October 1995 on the protection of individuals with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data, OJ L 281, 23.11.1995, p.31.

- 28.Hagglund M, Walden M, Bahr R, et al. Methods for epidemiological study of injuries to professional football players: developing the UEFA model. Br J Sports Med 2005;39:340–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Birrer RB. Trauma epidemiology in the martial arts. The results of an eighteen-year international survey. Am J Sports Med 1996;24(6 Suppl):S72–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kazemi M, Pieter W. Injuries at the canadian national tae kwon do championships: A prospective study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2004;5:22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pieter W, Van Ryssegem G, Lufting R, et al. Injury situation and injury mechanism at the 1993 european taekwondo cup. J Hum Mov Stud 1995;28:1–24 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pieter W, Bercades LT, Heijmans J. Injuries in young and adult taekwondo ahtletes. Kines 1998;30:22–30 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pieter W, Zemper ED. Injuries in adult American taekwondo athletes. Fifth IOC World Congress on Sports Sciences; 31 October–15 November 1999, Sydney, Australia, 1999a [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zemper ED, Pieter W. Injury rates during the 1988 US Olympic team trials for taekwondo. Br J Sports Med 1989;23:161–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zetaruk MN, Violan MA, Zurakowski D, et al. Injuries in martial arts: A comparison of five styles. Br J Sports Med 2005;39:29–33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kazemi M, Chudolinski A, Turgeon M, et al. Nine year longitudinal retrospective study of taekwondo injuries. J Can Chiropr Assoc 2009;53:272–81 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Siana J, Borum P, Kryger H. Injuries in taekwondo. Br J Sports Med 1986;20:165–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cunningham C, Cunningham S. Injury surveillance at a national multi-sport event. Aust J Sci Med Sport 1996;28:50–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim EH, Kim YS, Toun SW, et al. Survey and analysis of sports injuries and treatment patterns among Korean national athletes. Korean J Sports Sci 1994;6:33–56 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Myklebust G, Maehlum S, Holm I, et al. A prospective cohort study of anterior cruciate ligament injuries in elite Norwegian team handball. Scand J Med Sci Sports 1998;8:149–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Myklebust G, Engebretsen L, Braekken IH, et al. Prevention of anterior cruciate ligament injuries in female team handball players: a prospective intervention study over three seasons. Clin J Sport Med 2003;13:71–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Soderman K, Alfredson H, Pietila T, et al. Risk factors for leg injuries in female soccer players: A prospective investigation during one out-door season. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2001;9:313–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kazemi M, Waalen J, Morgan C, et al. A profile of Olympic taekwondo competitors. J Sports Sci Med 2006;5:114–21 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kazemi M, Perri G, Soave D. A profile of 2008 Olympic taekwondo competitors. J Can Chiropr Assoc 2010;54:243–9 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.