Abstract

Tocopherols (vitamin E) are lipid-soluble antioxidants produced by all plants and algae, and many cyanobacteria, yet their functions in these photosynthetic organisms are still not fully understood. We have previously reported that the vitamin E deficient 2 (vte2) mutant of Arabidopsis thaliana is sensitive to low temperature (LT) due to impaired transfer cell wall (TCW) development and photoassimilate export associated with massive callose deposition in transfer cells of the phloem. To further understand the roles of tocopherols in LT induced TCW development we compared the global transcript profiles of vte2 and wild-type leaves during LT treatment. Tocopherol deficiency had no significant impact on global gene expression in permissive conditions, but significantly affected expression of 77 genes after 48 h of LT treatment. In vte2 relative to wild type, genes associated with solute transport were repressed, while those involved in various pathogen responses and cell wall modifications, including two members of callose synthase gene family, GLUCAN SYNTHASE LIKE 4 (GSL4) and GSL11, were induced. However, introduction of gsl4 or gsl11 mutations individually into the vte2 background did not suppress callose deposition or the overall LT-induced phenotypes of vte2. Intriguingly, introduction of a mutation disrupting GSL5, the major GSL responsible for pathogen-induced callose deposition, into vte2 substantially reduced vascular callose deposition at LT, but again had no effect on the photoassimilate export phenotype of LT-treated vte2. These results suggest that GSL5 plays a major role in TCW callose deposition in LT-treated vte2 but that this GSL5-dependent callose deposition is not the primary cause of the impaired photoassimilate export phenotype.

Keywords: tocopherols, transfer cells, callose synthase, Arabidopsis, sugar export, antioxidants, phloem parenchyma cells

Introduction

Tocopherols are essential nutrients in mammals and, together with tocotrienols, are collectively known as vitamin E (Evans and Bishop, 1922; Bramley et al., 2000; Schneider, 2005). As lipid-soluble antioxidants tocopherols quench singlet oxygen and scavenge lipid peroxyl radicals and hence terminate the autocatalytic chain reaction of lipid peroxidation (Tappel, 1972; Fahrenholtz et al., 1974; Burton and Ingold, 1981; Liebler and Burr, 1992; Kamal-Eldin and Appelqvist, 1996). Tocopherols are localized in biological membranes and associated with highly unsaturated fatty acids, and thus may also affect membrane properties, such as permeability and stability of membranes (Erin et al., 1984; Kagan, 1989; Stillwell et al., 1996; Wang and Quinn, 2000).

Tocopherols are synthesized only in photosynthetic organisms, including all plants and algae, and some cyanobacteria. However, tocopherol functions in these organisms remain poorly understood. The tocopherol-deficient vte2 (vitamin e 2) mutant of Arabidopsis thaliana is defective in homogentisate phytyl transferase (HPT), the first committed enzyme of the pathway, and lacks all tocopherols and pathway intermediates (Collakova and DellaPenna, 2001; Savidge et al., 2002; Sattler et al., 2004; Mene-Saffrane et al., 2010). The vte2 mutants exhibit reduced seed viability and defective seedling development associated with elevated lipid peroxidation (Sattler et al., 2004; Mene-Saffrane et al., 2010; DellaPenna and Mene-Saffrane, 2011), demonstrating that a primary role of tocopherols is to limit non-enzymatic lipid oxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), especially during seed desiccation and seedling germination. Transcript profiling studies further confirmed the importance of non-enzymatic lipid oxidation in triggering the oxidative and defense responses in germinating seeds of vte2 (Sattler et al., 2006).

In contrast to the drastic vte2 seedling phenotype, the vte2 mutants that do survive early seedling development become virtually indistinguishable from wild type under permissive conditions and also under high light stress (Sattler et al., 2004; Maeda et al., 2006), suggesting that tocopherols are dispensable in mature plants even under highly photooxidative stress conditions. However, when tocopherol-deficient Arabidopsis plants are subjected to low temperature (LT) they developed a series of biochemical and physiological phenotypes (Maeda et al., 2006). As early as 6 h after LT treatment the vte2 mutants exhibit an impairment of photoassimilate export. This transport phenotype is accompanied by an unusual deposition of cell wall materials (i.e., callose) in the vasculature which likely creates a bottleneck for photoassimilate transport. Reduced photoassimilate export subsequently leads to carbohydrate and anthocyanin accumulation in source leaves, feedback inhibition of photosynthesis and ultimately growth inhibition of whole plants at LT (Maeda et al., 2006). This LT phenotype was independent of light level and was not associated with typical symptoms of photooxidative stress (i.e., photoinhibition, photobleaching, accumulation of zeaxanthin, or lipid peroxides) (Maeda et al., 2006).

The carbohydrate accumulation and callose deposition phenotypes of LT-treated vte2 resemble the phenotypes of maize sucrose export defective 1 (sxd1) and potato SXD1-RNAi lines, which are also tocopherol deficient and accumulate carbohydrates without LT treatment (Russin et al., 1996; Provencher et al., 2001; Sattler et al., 2003; Hofius et al., 2004). Thus, a role for tocopherols in phloem loading is conserved among different plants with the unique, LT-inducibility of Arabidopsis vte2 mutant phenotype providing a useful tool to dissect the underlying mechanism. Detailed ultrastructure analysis of the vasculature of the Arabidopsis vte2 mutant during a LT time course revealed that callose deposition occurred before significant accumulation of carbohydrate and is restricted to the transfer cell wall (TCW) of phloem parenchyma cells adjacent to the companion cell/sieve element complex (Maeda et al., 2006). While the TCW is usually characterized by invaginated wall ingrowth toward the cytoplasm (Haritatos et al., 2000; Talbot et al., 2002; McCurdy et al., 2008), the phloem parenchyma cells of LT-treated vte2 developed abnormally thickened TCW with irregular shaped ingrowths and massive callose deposition (Maeda et al., 2006). These results demonstrated that TCW-specific callose deposition is tightly linked with the defective photoassimilate export phenotype and is not a secondary effect caused by carbohydrate accumulation. However, the molecular mechanism underlying the callose deposition remains to be determined as does whether impaired phloem loading is due to vascular callose deposition in TCWs in the tocopherol-deficient mutants.

Analysis of membrane lipid composition in wild-type Arabidopsis and the vte2 mutant during LT treatment further revealed that tocopherol deficiency in plastids alters the PUFA composition of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) derived membrane lipids prior to LT treatment (Maeda et al., 2008). Subsequently, mutations in FATTY ACID DESATURASE 2 (FAD2) and TRIGALACTOSYLDIACYLGLYCEROL 1 (TGD1), encoding the ER-localized oleate desaturase and the ER-to-plastid lipid ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter, respectively, were identified as suppressors of the vte2 LT-induced phenotypes (sve loci) (Maeda et al., 2008; Song et al., 2010). These results provided biochemical and genetic evidence that alterations in extra-plastidic lipid metabolism are an upstream event in the initiation and development of the vte2 LT-induced phenotypes (Maeda et al., 2008; Song et al., 2010). The unexpected role of plastid-localized tocopherols in ER lipid metabolism has led to the recent discovery of a novel mechanism allowing biochemical continuity between the ER and chloroplast membranes (Mehrshahi et al., 2013). However, further investigation is required to understand the molecular links between tocopherol deficiency, lipid metabolism, and reduced photoassimilate export in LT-treated vte2.

In this study, microarray analysis of wild-type Arabidopsis and the vte2 mutant was used to investigate the effects of tocopherol deficiency on global gene expression at both permissive and LT conditions. While multiple studies have investigated transcriptome responses to vitamin E deficiency in animals (Barella et al., 2004; Rota et al., 2004, 2005; Nell et al., 2007; Oommen et al., 2007), no global gene expression profile of the effect of tocopherols in photosynthetic tissues has hitherto been undertaken in plants. Although almost no changes were observed in genome wide transcription between wild type and vte2 under permissive conditions, 77 genes were identified as being differentially expressed in vte2 compared to wild type in response to LT-treatment. Attempts to genetically suppress transfer cell callose deposition by introducing mutations for two GLUCAN SYNTHASE LIKE (GSL) genes, whose expression was strongly induced in LT treated vte2, or a mutation in GSL5, previously shown to be the primary GSL responsible for callose deposition in response to pathogen ingress, demonstrated that GSL5 is responsible for the majority of the LT-induced vasculature callose deposition in vte2. However, genetic elimination of this GSL5-dependent callose deposition showed that it is not the direct cause of the LT-induced photoassimilate export phenotype of vte2.

Materials and methods

Plant materials and growth conditions

Arabidopsis plants were grown and treated at LT as described previously (Maeda et al., 2008). Briefly, seed were stratified for 4–7 days (4°C), planted in an equal mixture of vermiculite, perlite, and soil with 1 × Hoagland solution, and grown under permissive conditions: 12 h, 120 μmol photon m−2 s−1 light at 22°C/12 h darkness at 18°C and 70% relative humidity. Plants were watered every other day and with a half strength Hoagland solution once a week. For LT treatments, 4-week-old plants were transferred at the beginning of the light cycle to 12 h, 120 μmol photon m−2 s−1 light/12 h darkness at 7°C. For microarray analysis, the 9–11th oldest rosetta leaves from three independent plants were harvested together into a tube filled with liquid nitrogen 1 h into the light cycle after 48 and 120 h of LT-treatment or without LT-treatment (referred to as 0 h LT treatment).

RNA extraction, labeling, and hybridization for microarray

Total RNA was extracted using the RNAqueous RNA extraction kit and the Plant RNA Isolation Aid (Ambion) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Labeling and hybridization of RNA were conducted using standard Affymetrix protocols by the Michigan State University DNA Microarray Facility. ATH1 Arabidopsis GeneChips (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA) were used for measuring changes in gene expression levels. Total RNA was converted into cDNA, which was in turn used to synthesize biotinylated cRNA. The cRNA was fragmented into smaller pieces and then was hybridized to the GeneChips. After hybridization, the chips were automatically washed and stained with streptavidin phycoerythrin using a fluidics station. The chips were scanned by the GeneArray scanner at 570 nm emission and 488 nm excitation.

Microarray data evaluation and preprocessing

Raw chip data were analyzed with R software (version 2.9, http://www.r-project.org/). Because of various problems associated with mismatch (MM) probes (Bolstad et al., 2003; Irizarry et al., 2003), only perfect match (PM) probe intensities were used. To assess data quality, the AffyRNAdeg and QCReport functions in the simpleaffy package were used to generate the RNA degradation (Supplemental Figure S1) and quality control (QC) plots (Supplemental Figure S2) for all 18 chips. The Boxplot tool included in the affy and simpleaffy packages were used to investigate the data distribution of the 18 chips (Supplemental Figure S3). RMA function as implemented in the affy package was used for background adjustment, normalization and summarization. A cluster dendrogram (Figure 1) was generated by applying hclust function using average linkage clustering of Euclidean distance based on the normalized expression values from 18 chips.

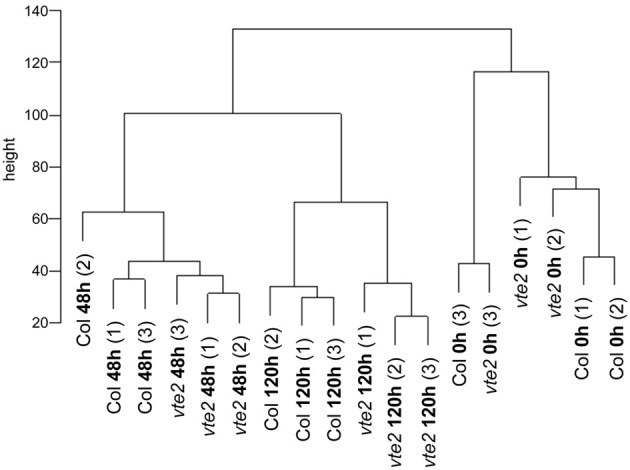

Figure 1.

A cluster dendrogram of a correlation matrix for all-against-all chip comparisons. The scale on the vertical bar “height” indicates Manhattan distance. The numbers (1) to (3) indicate three independent biological replications for treatments and genotypes. The samples cluster by different genotypes (Col and vte2) after LT treatment (48 and 120 h).

Statistical analyses for differentially expressed genes

Signal intensity data were analyzed with the use of a linear statistical model and an empirical Bayes method in the LIMMA package implemented in Bioconductor of R software (Smyth, 2005) to identify genes differentially expressed between genotypes at different time points of LT treatment. The p-values were adjusted for multiple testing with the Benjamini and Hochberg method to control the false discovery rate (Benjamini and Hochberg, 1995). Genes with adjusted p-values < 0.05 were considered significant. A heat map of the 77 significantly different genes in vte2 at 48 h of LT treatment was generated using the average linkage clustering of Euclidean distance based on the normalized average expression values for each genotype and timepoint.

The 49 genes that were significantly induced in 48 h LT-treated vte2 relative to wild-type (Col) plants (Table 1) were also examined using the Meta-Analyzer feature of GENEVESTIGATOR (Zimmermann et al., 2004) to assess their responses to various conditions or treatments. The gene expression responses were calculated as ratios between a given treatment and its negative control with the resulting values reflecting up- or down-regulation of genes by a treatment. Twelve different stress conditions were chosen: Biotic stress treatments with Botrytis cinerea (6 treatment chips + 6 control chips), Pseudomonas syringae (3 + 3), and Myzus persicae (3 + 3). Chemical stress treatments were hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) (3 + 2) and ozone (3 + 3). Hormone stress treatments were with abcisic acid (ABA, 2 + 2), ethylene (3 + 3), indole acidic acid (IAA, 3 + 3), and zeatin (3 + 3). Abiotic stress treatments were cold (3 + 3), drought (3 + 1), and heat (2 + 2). All experiments selected from GENEVESTIGATOR utilized mature leaves except for the hormone treatment data sets (ethylene, IAA, and zeatin) that were performed on seedlings. In addition, to compare the transcriptional responses to tocopherol deficiency in seedlings and mature plants (Table 3), microarray data for 0-day and 3-day-old seedlings of Col and vte2 (three biological replicates for each treatment and genotype, see Sattler et al., 2006) were subjected to the same procedure of preprocessing and statistical analysis as described above for vte2 plants under LT treatment.

Table 1.

The 49 genes significantly upregulated in vte2 relative to Col at 48 h of LT treatment.

| AGI number | Ma | adj-P.valueb | Bc | Annotated gene functiond |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| At1g26450 | 2.62 | 0.00 | 11.64 | Beta-1,3-glucanase-related |

| At4g23410 | 1.53 | 0.00 | 10.08 | Senescence-associated family protein |

| At1g68290 | 2.39 | 0.00 | 7.97 | Bifunctional nuclease, putative |

| At5g22860 | 1.38 | 0.00 | 7.04 | Serine carboxypeptidase S28 family protein |

| At3g14570 | 1.85 | 0.00 | 6.88 | Glycosyl transferase family 48 protein (glucan synthase like 4, GSL4) |

| At1g59500 | 1.58 | 0.00 | 6.79 | Auxin-responsive GH3 family protein |

| At3g17690 | 1.80 | 0.00 | 6.74 | Cyclic nucleotide-binding transporter 2/CNBT2 |

| At1g74590 | 1.50 | 0.00 | 6.31 | Glutathione S-transferase, putative |

| At4g20320 | 1.08 | 0.00 | 5.80 | CTP synthase, putative/UTP-ammonia ligase, putative |

| At3g22910 | 1.82 | 0.00 | 5.65 | Ca-transporting ATPase, plasma membrane-type, putative (ACA13) |

| At5g13080 | 1.88 | 0.00 | 5.51 | WRKY family transcription factor (WRKY75) |

| At5g47920 | 1.06 | 0.00 | 5.13 | Expressed protein |

| At1g68620 | 2.08 | 0.00 | 4.95 | Expressed protein |

| At1g65500 | 2.13 | 0.00 | 4.84 | Expressed protein |

| At1g76640 | 2.52 | 0.00 | 4.54 | Calmodulin-related protein, putative |

| At2g26020 | 2.01 | 0.00 | 4.40 | Plant defensin-fusion protein, putative (PDF1.2b) |

| At1g74055 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 4.18 | Expressed protein |

| At1g30370 | 1.60 | 0.01 | 3.80 | Lipase class 3 family protein |

| At5g13880 | 1.45 | 0.01 | 3.60 | Expressed protein |

| At3g49130 | 0.94 | 0.01 | 3.16 | Hypothetical protein |

| At5g46590 | 1.31 | 0.01 | 3.09 | No apical meristem (NAM) family protein |

| At3g21780 | 0.91 | 0.01 | 3.09 | UDP-glucosyl transferase family protein |

| At1g17180 | 1.21 | 0.02 | 2.82 | Glutathione S-transferase, putative |

| At1g65610 | 1.33 | 0.02 | 2.70 | Endo−1,4-beta-glucanase, putative/cellulase, putative |

| At3g53600 | 0.70 | 0.02 | 2.39 | Zinc finger (C2H2 type) family protein |

| At5g13170 | 1.01 | 0.02 | 2.37 | Nodulin MtN3 family protein |

| At5g46350 | 1.02 | 0.02 | 2.34 | WRKY family transcription factor (WRKY8) |

| At5g09470 | 0.93 | 0.02 | 2.26 | Mitochondrial substrate carrier family protein |

| At4g35730 | 1.24 | 0.02 | 2.23 | Expressed protein |

| At2g29090 | 1.07 | 0.03 | 2.15 | Cytochrome P450 family protein |

| At2g30550 | 0.70 | 0.03 | 2.08 | Lipase class 3 family protein |

| At4g38420 | 1.58 | 0.03 | 2.02 | Multi-copper oxidase type I family protein |

| At4g27260 | 0.76 | 0.03 | 1.98 | Auxin-responsive GH3 family protein |

| At3g59100 | 1.04 | 0.03 | 1.81 | Glycosyl transferase family 48 protein (glucan synthase like 11, GSL11) |

| At4g19460 | 0.80 | 0.03 | 1.80 | Glycosyl transferase family 1 protein |

| At3g09270 | 2.07 | 0.03 | 1.73 | Glutathione S-transferase, putative |

| At5g22570 | 1.18 | 0.03 | 1.72 | WRKY family transcription factor (WRKY38) |

| At1g32350 | 1.45 | 0.04 | 1.64 | Alternative oxidase, putative |

| At5g17330 | 0.74 | 0.04 | 1.54 | Glutamate decarboxylase 1 (GAD 1) |

| At4g28550 | 1.05 | 0.04 | 1.43 | RabGAP/TBC domain-containing protein |

| At5g65600 | 1.27 | 0.04 | 1.38 | Legume lectin family protein/protein kinase family protein |

| At4g36430 | 0.79 | 0.04 | 1.37 | Peroxidase, putative |

| At5g04080 | 0.63 | 0.04 | 1.32 | Expressed protein |

| At5g64905 | 1.78 | 0.04 | 1.25 | Expressed protein |

| At5g66920 | 1.09 | 0.04 | 1.24 | Multi-copper oxidase type I family protein |

| At5g63970 | 0.97 | 0.05 | 1.20 | Copine-related |

| At2g23270 | 0.95 | 0.05 | 1.20 | Expressed protein |

| At1g19250 | 0.86 | 0.05 | 1.10 | Flavin-containing monooxygenase family protein |

| At5g67080 | 1.69 | 0.05 | 1.08 | Protein kinase family protein |

M-value (M) is the value of the contrast and represents a log2 fold change between 48 h-LT-treated vte2 and Col.

adj-P.value is the p-value adjusted for multiple testing with Benjamini and Hochberg's method to control the false discovery rate.

B-statistic (B) is the log-odds that the gene is differentially expressed.

Annotation was obtained from the Gene Ontology of The Arabidopsis Information Resources.

Table 3.

The 12 genes that are common between the 77 significantly different genes in 48 h-LT-treated vte2 plant and 744 significantly different genes in 3-d-old vte2 seedling.

| AGI number | 48 h-LT-treated vte2 plant | 3-day-old vte2 seedling | Gene titlec | GO molecular functionc | GO cellular componentc | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ma | adj-P.valueb | Ma | adj-P.valueb | ||||

| At1g68290 | 2.39 | 0.00 | 2.01 | 0.00 | Bifunctional nuclease, putative | Nucleic acid binding/endonuclease activity | Endomembrane system |

| At1g65500 | 2.13 | 0.00 | 4.33 | 0.00 | Expressed protein | – | Endomembrane system |

| At1g74590 | 1.50 | 0.00 | 2.19 | 0.00 | Glutathione S-transferase | Glutathione transferase activity | Cytoplasm |

| At5g46590 | 1.31 | 0.01 | 1.93 | 0.00 | No apical meristem (NAM) family protein | Transcription factor activity/DNA binding | – |

| At1g17180 | 1.21 | 0.02 | 1.93 | 0.03 | Glutathione S-transferase | Glutathione transferase activity | Cytoplasm |

| At5g46350 | 1.02 | 0.02 | 1.69 | 0.00 | WRKY family transcription factor (WRKY8) | Transcription factor activity/DNA binding | Nucleus |

| At3g09270 | 2.07 | 0.03 | 1.29 | 0.02 | Glutathione S-transferase | Glutathione transferase activity | Cytoplasm |

| At2g30550 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 1.02 | 0.05 | Lipase class 3 family protein | Triacylglycerol lipase activity | Chloroplast |

| At4g36430 | 0.79 | 0.04 | 3.20 | 0.00 | Peroxidase, putative | Peroxidase activity/calcium ion binding/oxidoreductase activity | Endomembrane system |

| At5g64905 | 1.78 | 0.04 | 1.10 | 0.01 | Expressed protein | – | – |

| At1g76800 | −1.43 | 0.00 | −0.74 | 0.02 | Nodulin, putative | – | – |

| At3g09580 | −0.73 | 0.05 | −0.90 | 0.02 | Amine oxidase family protein | Oxidoreductase activity | Chloroplast |

M-value (M) is the value of the contrast and represents a log2 fold change.

adj-P.value, the p-value adjusted for multiple testing with Benjamini and Hochberg's method to control the false discovery rate, were shown for 48 h-LT-treated vte2 plant and 3-d-old vte2 seedling, respectively.

Descriptions of gene function and cellular component were obtained from the Gene Ontology section of The Arabidopsis Information Resources.

Expression profiles of 0-day and 3-day-old seedling of Col and vte2 were subjected to the same process of limma analysis for analysis of significant genes in 48 h-LT-treated vte2 plants (see Materials and Methods). The list of 744 differentially expressed genes in 3-day-old vte2 seedlings was compared with the list of 77 differentially expressed genes in 48 h-LT-treated vte2 plants and overlapping 12 genes were listed.

Generation of mutant genotypes

The following gsl mutant lines were obtained from the Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center at Ohio State University: SALK_000507 for GSL4 (with a T-DNA insert in exon 34 of At3g14570), gsl5-1/pmr4-1 for GSL5 (with a non-sense mutation in exon 2 of At4g03550), and SALK_019534 for GSL11 (with a T-DNA insert in exon 15 of At3g59100). Homozygous mutant lines for gsl5-1 were identified by PCR using CAPs genotyping primers (Nishimura et al., 2003). Homozygous mutants for gsl4 and gsl11 were identified by PCR using gene specific primers; 5′ - TTGCCTGAGAGGATTAGCAAG −3′ (forward) and 5′ -TTGAAGGATACAAGGACGTGG −3′ (reverse) for gsl4 and 5′ -TCACACCTTCATTCCCTGTTC −3′ (forward) and 5′-GTTCCTGTGTAAGGCCTCATG −3′ (reverse) for gsl11. The double homozygous mutant genotypes vte2 gsl4, vte2 gsl5, and vte2 gsl11 were obtained by HPLC analysis for tocopherol deficiency (Collakova and DellaPenna, 2001) and the above mentioned PCR-based genotyping for gsl homozygosity. vte2 homozygosity was also confirmed by a CAPs marker developed for the vte2-1 point mutation (Maeda et al., 2006). Plants of Col, vte2, the single mutants of gsl4, gsl5, gsl11, and the three double mutants were grown for 4 weeks at permissive conditions and then transferred to LT conditions for the time periods, indicated in each figure legend for evaluation of different LT-induced phenotypes. Optimal time points were chosen based on our previous time-course analysis of the appearance of different LT-induced vte2 phenotypes (Maeda et al., 2006, 2008).

14C photoassimilate labeling and analysis of sugars

Analyses for leaf glucose, fructose, and sucrose levels were performed as previously described (Maeda et al., 2006). 14CO2 labeling of photoassimilate and measurement of phloem exudation were also carried out as described (Maeda et al., 2006) except that 10 mM EDTA was used for exudation buffer and 0.05 mCi of NaH14CO3 was used per labeling experiment. Phloem exudates were collected after 5 h of exudation.

Fluorescence and transmission electron microscopy

Leaves were prepared for aniline blue fluorescence microscopy and staining and visualization were performed as described (Maeda et al., 2006) except that the gain adjustment of the camera was set to 2.0 for images in Figures 4B, 5A. Leaves were prepared for transmission electron microscopy and immunolocalization of β-1,3-glucan as described (Maeda et al., 2006).

Figure 4.

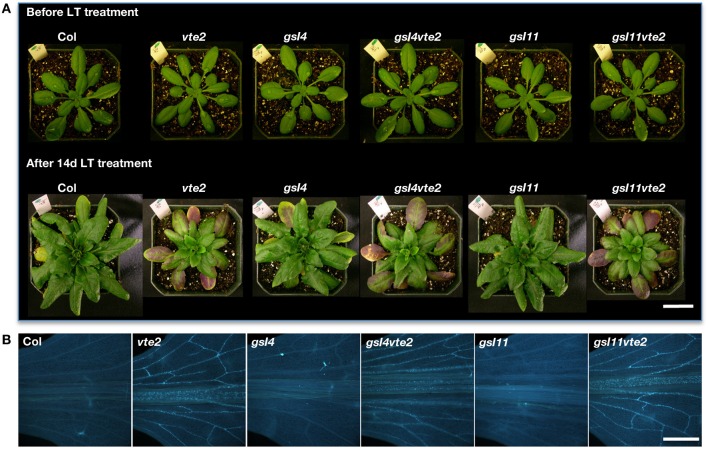

Whole plant and vascular callose phenotypes of Col, vte2, gsl4, gsl4 vte2, gsl11, and gsl11 vte2. All genotypes were grown under permissive conditions for 4 weeks and then transferred to LT conditions for the specified periods previously shown to maximize each phenotype (Maeda et al., 2006). (A) Whole plant phenotype of the indicated genotypes before (top) and after (bottom) 28 days of LT treatment. Bar = 2 cm. (B) Aniline-blue positive fluorescence in the lower portions of leaves after 3 days of LT treatment. Samples for callose staining were fixed in the middle of the light cycle. Representative images are shown (n = 3). Bar = 1 mm.

Figure 5.

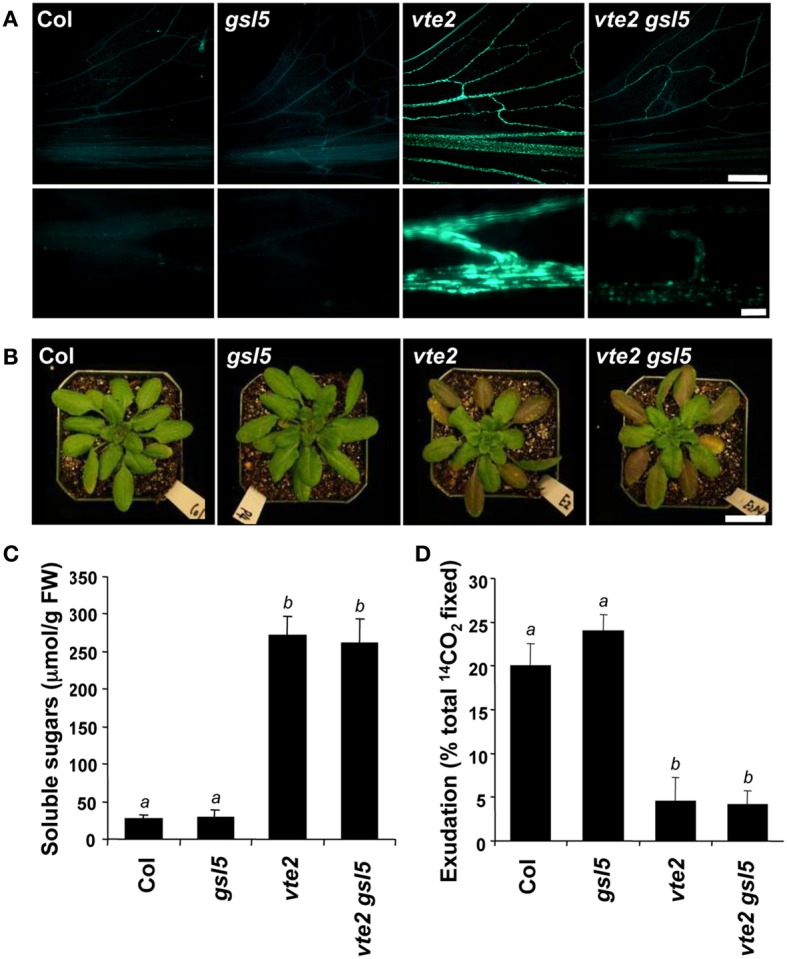

Characterization of the gsl5 vte2 mutant at LT. Col, gsl5, vte2, and gsl5 vte2 were grown under permissive conditions for 4 weeks and transferred to LT conditions for the indicated times previously shown to maximize each phenotype (Maeda et al., 2006). (A) Aniline-blue positive fluorescence in the lower portions of leaves after 7 days of LT treatment. Samples for callose staining were fixed in the middle of the light cycle. Representative images are shown (n = 3). The bottom panels are higher magnification pictures of vasculature. Bars = 1 mm (top) and 100 μm (bottom). (B) Whole plant phenotypes after 2 weeks of LT treatment. Bar = 2 cm. (C) Total soluble sugar content of mature leaves after 2 weeks of LT treatment. Data are means ± SD (n = 5). Non-significant groups are indicated by a and b (P < 0.05). (D) 14C-labeled photoassimilate export capacity of mature leaves after one additional week of LT treatment. Data are means ± SD (n = 5). Non-significant groups are indicated by a and b (P < 0.05).

Results

Tocopherol deficiency has little impact on global gene expression at permissive conditions

To identify changes in gene expression that might be specifically related to the absence of tocopherols, global transcript profiles were compared between vte2 and Col plants grown under permissive conditions for 4 weeks, when they are physiologically and biochemically indistinguishable, and at two time points of LT treatment (48 and 120 h) selected based on our previous timecourse study of the physiological and biochemical changes of vte2 and Col during LT treatment (Maeda et al., 2006). After 48 h of LT, vascular callose deposition is strongly induced and photoassimilate export capacity is significantly lower in vte2 compared to Col, though the visible whole plant phenotypes and soluble sugar accumulation between the two genotypes do not differ (Maeda et al., 2006). The 120 h LT timepoint represents a relatively late response time point when soluble sugars are significantly higher and callose deposition is even more extensive and wide spread in vte2 (Maeda et al., 2006). Thus the 48 h time point should allow identification of early responses to tocopherol deficiency that are distinct from later, pleiotropic responses resulting from the strongly elevated sugar levels in vte2 after 120 h of LT. The 0 h time point represents the absence of LT treatment (see Materials and Methods) and serves as a critical treatment control.

The vte2 LT experiment comprised 18 chips in a factorial design. Three independent biological replicates were conducted for Col and vte2 at each of the three time points, allowing rigorous statistical analysis of the data obtained. When the relationship of chips was examined by a cluster dendrogram, three clusters consistent with the three time points of LT treatment were apparent (Figure 1). The 48 and 120 h LT-treated samples were more closely related to each other than to the 0 h data, suggesting that the effect of LT treatment was greater than effects due to genotypic differences.

To investigate if tocopherol deficiency leads to any transcriptional changes before LT treatment, the linear models for microarray data (limma) analysis (Smyth, 2005) was performed to detect differently expressed genes between vte2 and Col at 0 h (see Materials and Methods). With the exception of At2g18950, which encodes the mutated gene in the background (VTE2/HPT, Collakova and DellaPenna, 2003), no other statistically significant differences (at adjusted p-values of < 0.05) were observed. These data indicate that the lack of tocopherols per se has little impact on global gene expression in mature vte2 plants under permissive conditions.

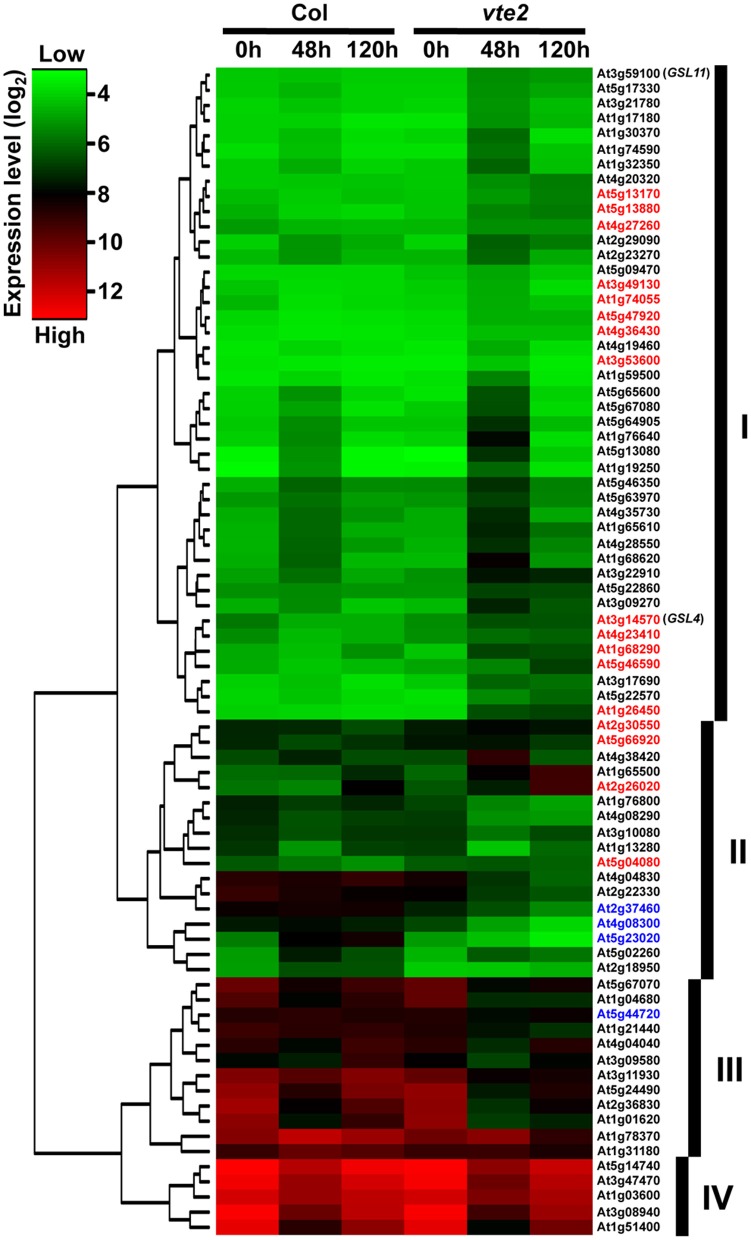

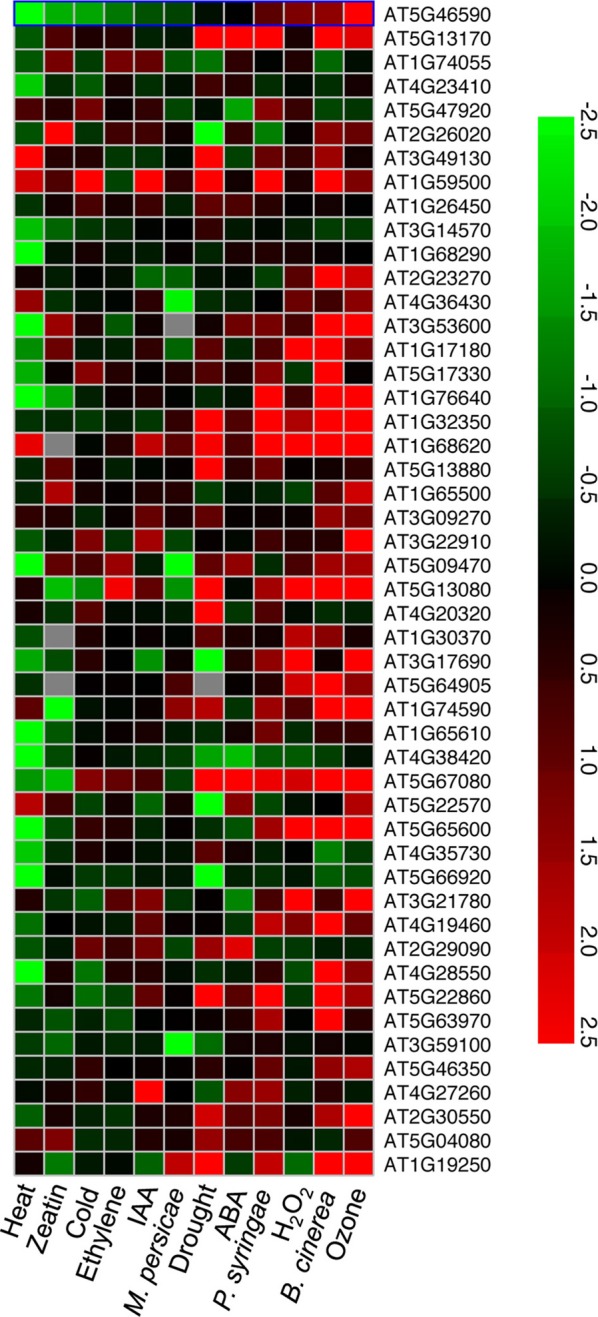

Identification of differentially expressed genes in 48 h-LT-treated vte2 and Col

After 48 h at LT, 77 probe sets were found to be significantly different between vte2 and Col: 49 genes were significantly induced (Table 1) and 28 were significantly repressed (Table 2) in vte2 relative to Col. The expression patterns of these 77 genes across all time points are visualized in the gene tree in Figure 2. As discussed above, before LT treatment (0 h) expression levels of all genes are very similar between Col and vte2 and changed differently between genotypes after LT treatment. Group I contains 43 genes whose expression is generally low at 0 h and induced in both Col and vte2 after LT treatment, with induction in vte2 being stronger and more persistent. Group II contains 17 genes whose expression is somewhat high at 0 h and then more strongly induced or repressed in vte2 after LT treatment compared to Col. Group III (12 genes) and IV (5 genes) are expressed at moderately and very high levels at 0 h, respectively, and both repressed at LT more strongly and persistently in vte2 than Col. Several genes in groups I, II, and III show opposite expression patterns in vte2 and Col from 0 to 48 h of LT treatment (highlighted in red for induced or blue for repressed in vte2 relative to Col, respectively) and are particularly interesting as they represent potential “marker genes” that are specifically impacted by tocopherol deficiency at LT.

Table 2.

The 28 genes significantly downregulated in vte2 relative to Col at 48 h of LT treatment.

| AGI number | Ma | adj-P.valueb | Bc | Annotated gene functiond |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| At2g18950 | −2.36 | 0.00 | 7.93 | HPT: tocopherol phytyltransferase |

| At5g14740 | −0.77 | 0.00 | 6.32 | Carbonate dehydratase 2 (CA2) (CA18) |

| At3g11930 | −1.47 | 0.00 | 6.10 | Universal stress protein (USP) family protein |

| At2g36830 | −1.01 | 0.00 | 5.94 | Major intrinsic family protein/MIP family protein |

| At1g04680 | −0.74 | 0.00 | 5.41 | Pectate lyase family protein |

| At1g76800 | −1.43 | 0.00 | 5.36 | Nodulin, putative |

| At4g08300 | −2.98 | 0.00 | 4.58 | Nodulin MtN21 family protein |

| At2g22330 | −1.67 | 0.00 | 4.44 | Cytochrome P450, putative |

| At3g10080 | −0.72 | 0.01 | 3.86 | Germin-like protein, putative |

| At5g44720 | −1.05 | 0.02 | 2.89 | Molybdenum cofactor sulfurase family protein |

| At5g23020 | −3.81 | 0.02 | 2.88 | 2-isopropylmalate synthase 2 (IMS2) |

| At3g47470 | −0.84 | 0.02 | 2.77 | Chlorophyll A-B binding protein 4, chloroplast/LHCI type III CAB-4 (CAB4) |

| At1g51400 | −0.88 | 0.02 | 2.61 | Photosystem II 5 kD protein |

| At4g08290 | −1.22 | 0.02 | 2.56 | Nodulin MtN21 family protein |

| At1g21440 | −1.17 | 0.03 | 2.18 | Mutase family protein |

| At1g01620 | −0.83 | 0.03 | 2.02 | Plasma membrane intrinsic protein 1C (PIP1C)/aquaporin PIP1.3 (PIP1.3)/transmembrane protein B (TMPB) |

| At3g08940 | −0.82 | 0.03 | 1.95 | Chlorophyll A-B binding protein (LHCB4.2) |

| At5g24490 | −1.22 | 0.03 | 1.91 | 30S ribosomal protein, putative |

| At4g04830 | −1.57 | 0.04 | 1.58 | Methionine sulfoxide reductase domain-containing protein |

| At2g37460 | −1.93 | 0.04 | 1.54 | Nodulin MtN21 family protein |

| At4g04040 | −0.69 | 0.04 | 1.44 | Pyrophosphate–fructose-6-phosphate 1-phosphotransferase beta subunit, putative |

| At1g31180 | −0.85 | 0.04 | 1.41 | 3-isopropylmalate dehydrogenase, chloroplast, putative |

| At1g78370 | −1.07 | 0.04 | 1.40 | Glutathione S-transferase, putative |

| At5g02260 | −1.23 | 0.04 | 1.38 | Expansin, putative (EXP9) |

| At5g67070 | −0.51 | 0.04 | 1.28 | Rapid alkalinization factor (RALF) family protein |

| At1g13280 | −0.94 | 0.04 | 1.26 | Allene oxide cyclase family protein |

| At3g09580 | −0.73 | 0.05 | 1.08 | Amine oxidase family protein |

| At1g03600 | −0.48 | 0.05 | 1.08 | Photosystem II family protein |

M-value (M) is the value of the contrast and represents a log2 fold change between 48 h-LT-treated vte2 and Col.

adj-P.value is the p-value adjusted for multiple testing with Benjamini and Hochberg's method to control the false discovery rate.

B-statistic (B) is the log-odds that the gene is differentially expressed.

Annotation was obtained from the Gene Ontology of The Arabidopsis Information Resources.

Figure 2.

A gene tree of the 77 genes significantly altered in 48 h-LT-treated vte2 relative to Col (adjusted p-value < 0.05). The color bar represents expression levels (log2), with green to red being low to high expression. The groups (labeled as I, II, III, and IV) were based on general expression patterns across Col and vte2 at three time points of LT treatment. Genes showing opposite directions of expression from 0 to 48 h of LT treatment in Col and vte2 are highlighted in red (induced in vte2) or blue (repressed in vte2). See text for additional details.

Among the 49 induced genes at 48 h (Table 1), 6 are annotated as glycosyl transferases (At3g14570, At3g59100, At4g19460), UDP-glucosyl transferase (At3g21780), or glucanases (At1g26450, At1g65610). These genes are likely involved in aspects of cell wall modification, consistent with the major modifications to cell wall structure in phloem parenchyma cells of LT-treated vte2 (Maeda et al., 2006, 2008). Notably, LT treatment induced significant, albeit low, expression of two putative callose synthase genes, GSL4 (At3g14570) and GSL11 (At3g59100) in vte2 (Table 1). These genes are two members of the 12 member GSL callose synthase gene family in Arabidopsis and may contribute to the substantial callose deposition in transfer cells of LT-treated vte2. Other notable upregulated genes in LT-treated vte2 are involved in stress and senescence responses, various signaling pathways, and transcriptional regulation, including WRKY (At5g13080, At5g46350, At5g22570), NAM (At5g46590), and zinc finger (C2H2 type, At3g53600) transcription factors (Table 1).

The most significantly repressed gene in vte2 at 48 h LT (Table 2) was VTE2/HPT (At2g18950, Collakova and DellaPenna, 2003), the locus mutated in the vte2 background. Other downregulated genes of interest include a methionine sulfoxide reductase (At4g04830, EC 1.8.4.6), one member of a small gene family encoding enzymes that reduce oxidized methionine residues of proteins, and four genes encoding nodulin drug/metabolite transporters (Table 2). Nodulins are involved in nodulation of legume roots during symbiosis with Rhizobia, a process where extensive metabolite transport across peribacteroid membranes is required (Vandewiel et al., 1990; Hohnjec et al., 2009). Repression of these nodulins might be related to altered carbohydrate transport in LT-treated vte2.

The 49 genes induced in vte2 are not upregulated by abiotic stress per se

To investigate whether the 49 genes induced in LT-treated vte2 are part of a general stress response their expression patterns under diverse abiotic and biotic stress conditions were examined using publically available Arabidopsis microarray data (Figure 3). Approximately half of the 49 genes induced in LT-treated vte2 were also strongly and specifically upregulated by biotic treatments including the necrotrophic fungus Botrytis cinerea and pathogenic leaf bacterium Pseudomonas syringae but not the phloem-feeding aphid Myzus persicae. Interestingly, many of the genes that were upregulated by pathogen treatments were also induced by ozone treatment (Figure 3). These include most of the transcription factors (WRKY, NAM, and zinc finger family proteins) and some of the stress- and signaling-related genes (Glutathione S-transferases: At1g74590, At1g17180, At3g09270; auxin-responsive GH3 family proteins: At1g59500, At4g27260) induced in LT-treated vte2. In contrast, very few genes induced in LT-treated vte2 overlapped with genes responsive to abiotic stress conditions including heat, drought, and cold treatments or hormone treatments such as zeatin, IAA, ethylene, or ABA (Figure 3). These results suggest that the 49 genes with induced expression in LT-treated vte2 are due to tocopherol deficiency rather than a general response to cold or other abiotic stresses.

Figure 3.

A heat map of expression patterns for the 49 upregulated genes in 48 h LT-treated vte2 under other stress conditions. Genes (AGI number) significantly induced in 48 h LT-treated vte2 relative to Col plants were examined using the Meta-Analyzer feature of GENEVESTIGATOR to assess their responses to various stress conditions or treatments. The conditions and treatments shown were selected from GENEVESTIGATOR to represent a range of biotic, abiotic, and major hormone treatments and are sorted by increasing ratios from the left to the right. The color bar represents expression levels (log2) relative to each corresponding negative control in GENEVESTIGATOR.

A prior study showed that the transcriptome of germinating vte2 seedlings (at permissive conditions) is substantially influenced by elevated non-enzymatic lipid peroxidation occurring in the mutant at this developmental stage (Sattler et al., 2006). To compare transcriptional responses of LT-treated vte2 with those of 3-day-old vte2 seedlings, our preprocessing and statistical analysis approach was applied to germinating Col and vte2 seedling microarray datasets. Out of 744 genes identified as significantly different (adjusted p < 0.05) in 3-day-old vte2 seedlings relative to 3-day-old Col, only 12 were in common with the 77 significant altered genes in 48 h-LT-treated vte2 (Table 3). These results suggest that the majority of the transcriptional response of LT-treated vte2 plants is largely distinct from that of vte2 seedlings.

gsl4 and gsl11 have little impact on lt-induced vte2 callose deposition

Vascular-specific callose deposition is a phenotype shared by tocopherol-deficient mutants in several plant species (Russin et al., 1996; Hofius et al., 2004; Maeda et al., 2006). It has been suggested that vascular-specific callose deposition may directly block photoassimilate translocation and lead to the subsequent carbohydrate accumulation and growth inhibition phenotypes in tocopherol-deficient plants (Russin et al., 1996; Hofius et al., 2004; Maeda et al., 2006). To test this hypothesis we attempted to genetically eliminate induced callose deposition in vte2 by introducing mutations affecting specific callose synthase genes. Among the 12 GSL genes encoding putative callose synthases in the Arabidopsis genome (Richmond and Somerville, 2000; Hong et al., 2001), GSL4 (At3g14570) and GSL11 (At3g59100) were the only two family members whose expression was significantly altered in both 48 and 120 h LT-treated vte2 relative to Col (adjusted p-value < 0.01) (Table 1, Supplemental Figure S5). Homozygous mutants of GSL4 and GSL11 were therefore selected and introduced into the vte2 background (see Materials and Methods) and the single gsl and vte2 mutants and gsl4 vte2 and gsl11 vte2 double mutants were subjected to LT treatment to assess their phenotypes. Before LT treatment, the visible phenotypes of all the single and double mutants were similar to Col (Figure 4A). After prolonged LT treatment (28 days), which allows for full development of visible vte2 LT phenotypes (Maeda et al., 2006), the gsl4 and gsl11 mutants appeared similar to Col while both of the double mutants were smaller, purple and similar to vte2 (Figure 4A), indicating that neither the gsl4 nor gsl11 mutations have a substantial impact on the vte2 LT phenotype. The levels of LT-induced vascular callose deposition (an early phenotype, as described in Maeda et al., 2006) detectable by aniline-blue fluorescence after 3 days LT treatment was also indistinguishable between the vte2 single mutant and the gsl4 vte2 or gsl11 vte2 double mutants (Figure 4B). Thus, although GSL4 and GSL11 transcript levels are the only GSL family members induced higher in vte2 than Col in response to LT treatment, loss of either gene activity does not have a major impact on callose deposition in LT-treated vte2.

gsl5 attenuates the majority of callose deposition in vte2 without suppressing the photoassimilate export phenotype

Given that callose synthases are often post-transcriptionally regulated (Zavaliev et al., 2011), it is possible that enzymes responsible for the vascular-specific callose deposition of LT-treated vte2 may be post-transcriptionally induced and not identified as differentially expressed between vte2 and Col. GSL5 is the best characterized of the 12 GSLs in Arabidopsis and has been shown to be required for callose formation in response to wounding and fungal pathogens (Jacobs et al., 2003; Nishimura et al., 2003). Although GSL5 expression is modestly induced in response to LT-treatment and not differentially expressed in LT-treated vte2 relative to wild type (Table 1, Supplemental Figure S5), it might still play a role in the vascular callose deposition of vte2. To test this possibility we introduced the gsl5 mutation into the vte2 background and examined its effect on LT-induced vte2 phenotypes, including vascular callose deposition. Under permissive conditions, the gsl5 vte2 double mutant had a visible phenotype similar to Col, gsl5 and vte2 (Supplemental Figure S4). When 4 week-old plants were subjected to 7 days of LT treatment (which induces a stronger callose deposition phenotype than 3 days of LT treatment), vte2 exhibited the expected strong vascular-specific callose deposition, while no fluorescence signal was detectable in the vasculature of Col and gsl5 (Figure 5A). Although the gsl5 vte2 double mutant showed a substantial reduction in fluorescence intensity, weakly fluorescent spots were still present in the gsl5 vte2 vasculature (Figure 5A). However, despite the strong reduction in callose deposition at LT, photoassimilate export capacity, elevated soluble sugar content, and the visible phenotype of gsl5 vte2 were indistinguishable from that of vte2 (Figures 5B–D).

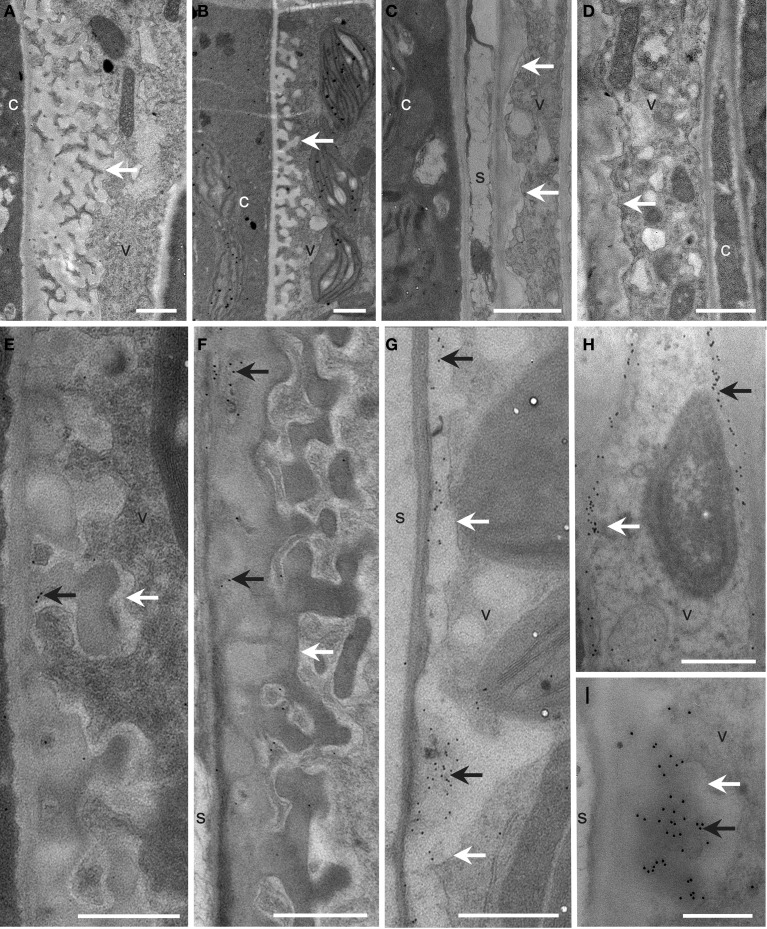

To further address the role of the remaining GSL5-independent callose deposition in gsl5 vte2, transmission electron microscopy was used to examine the ultrastructure and localization of callose in TCWs of Col, gsl5, vte2, and gsl5 vte2. The spatial organization and types of cells constituting the phloem and xylem of all genotypes were similar to prior reports (Haritatos et al., 2000; Maeda et al., 2006) and notable differences were observed only in the phloem parenchyma TCWs following 3 days of LT treatment. In all instances, cell wall differentiation ensued in phloem transfer cells of LT-treated plants. Both Col and gsl5 developed uniform TCWs adjacent to the companion cell/sieve element complex (Figures 6A,B,E,F), whereas those in vte2 and gsl5 vte2 were not uniform and were abnormally thickened to varying degrees (Figures 6C,D,G–I). The extensive localized globular outgrowths of wall commonly found in transfer cells of vte2 (Maeda et al., 2006) also developed in gsl5 vte2 but were less frequent. Positive immunolocalization with monoclonal antibodies to callose (β-1,3-glucan) showed it was present in TCWs at the companion cell/sieve element boundary in vte2 (Maeda et al., 2006), and also in gsl5 vte2 (Figures 6H,I). Immunolabeling of callose was sometimes present but mostly rare to absent in all cell types of Col and gsl5 (Figures 6E,F). These results indicate that although GSL5 is responsible for the bulk of detectable callose deposition in LT treated vte2 (Figure 5A), callose synthase(s) other than GSL5 initiate the LT-induced callose deposition in transfer cells of vte2 that may associate with the inhibition of photoassimilate export capacity in vte2.

Figure 6.

Cellular structure and immunodetection of callose after 3 days of LT treatment. Col, gsl5, vte2, and gsl5 vte2 were grown under permissive conditions for 4 weeks and transferred to LT conditions for 3 additional days. Col (A,E), gsl5 (B,F), vte2 (C,G), and gsl5 vte2 (D,H,I). Black arrows highlight wall ingrowths of phloem parenchyma transfer cells immunolabeled with anti-β-1,3-glucan. White arrows mark transfer cell walls. c, companion cell; s, sieve element; v, vascular parenchyma transfer cell. Bars = 1 μm (A–H), 0.5 μm (I).

Discussion

Genome wide transcriptional responses to tocopherol deficiency have been extensively studied in animals using α-tocopherol transfer protein knock-out mice (Ttpa−/−) (Gohil et al., 2003; Vasu et al., 2007, 2009) or animals fed with tocopherol-deficient diets (Barella et al., 2004; Rota et al., 2004, 2005; Nell et al., 2007; Oommen et al., 2007). In addition to oxidative stress related transcripts (Gohil et al., 2003; Jervis and Robaire, 2004; Hyland et al., 2006), tocopherols were found to modulate the expression of genes involved in hormone metabolism and apoptosis in the brain (Rota et al., 2005), lipid metabolism, inflammation, and immune system in the heart (Vasu et al., 2007), cytoskeleton modulation in lungs (Oommen et al., 2007), synaptic vesicular trafficking in liver (Nell et al., 2007), and muscle contractility and protein degradation in muscle (Vasu et al., 2009). In contrast to the broad effects of tocopherol deficiency on the animal transcriptome, we found that the absence of tocopherols in Arabidopsis leads to no significant changes in the global transcript profile of mature plants under permissive conditions. This finding extends a previous observation that Arabidopsis tocopherol-deficient mutants and wild type are virtually indistinguishable once they pass the oxidative stress bottlenecks of seed development and seedling germination (Maeda et al., 2006).

We previously showed that germinating seedlings of tocopherol-deficient Arabidopsis vte2 mutants exhibit massive levels of non-enzymatic lipid peroxidation (Sattler et al., 2004) resulting in differential expression of more than 700 genes when compared to wild type (Sattler et al., 2006). In contrast to these drastic biochemical and transcriptional changes in vte2 seedlings, lipid peroxidation was not detectable in mature vte2 leaves subject to LT treatment (Maeda et al., 2006, 2008) with only 77 genes having significantly altered expression (Tables 1, 2). Just 12 of these 77 genes are in common with the > 700 altered genes in vte2 seedlings, demonstrating that tocopherols play fundamentally distinct roles in seedlings and fully-expanded mature leaves. Moreover, of the 49 genes significantly upregulated in LT vte2 (Table 1), very few were also induced in response to other abiotic stresses (see Results). Instead approximately half of the 49 induced genes in LT vte2 were strongly and specifically upregulated by biotic and ozone treatments (Figure 3) with the latter significantly overlapping with transcriptional responses of plants to diseases (Eckeykaltenbach et al., 1994; Kangasjarvi et al., 1994; Ludwikow et al., 2004). Thus, in contrast to the strong oxidative response of the vte2 seedling transcriptome to germination, the transcriptome of mature vte2 Arabidopsis leaves subjected to LT show a very limited oxidative stress response.

Prior studies have highlighted the involvement of tocopherols in extra-plastidic lipid metabolism under LT conditions (Maeda et al., 2006, 2008; Song et al., 2010). Based on these results, it might be expected that some genes related to lipid metabolism would be differentially expressed in vte2 under LT. Surprisingly, however, only 2 of the 77 genes differentially expressed in LT-treated vte2 are involved in lipid metabolism. Both are lipase class 3 family proteins and proposed to have triacylglycerol lipase activities, with one (At2g30550) localized in the chloroplast and the other (At1g30370) to mitochondria. The majority of fatty acid desaturase genes in Arabidopsis, with the exception of FAD8 (Gibson et al., 1994), are not transcriptionally regulated in response to LT (Iba et al., 1993; Okuley et al., 1994; Heppard et al., 1996) or alterations in the membrane fatty acid composition (Falcone et al., 1994). Thus, it seems that changes in extra-plastidic lipid metabolism in LT-treated vte2 plants are not transcriptionally-regulated but rather are regulated at the post-transcriptional level.

As with biochemical analysis of LT treated plants, experimental materials for the current microarray analysis were of necessity taken from whole leaves (see Materials and Methods) and it is possible that vte2 LT transcriptional “signatures” related to altered lipid metabolism or TCW synthesis are present but are restricted to such a small portion of specialized cell types (e.g., transfer cells) that their signals are diluted and difficult to identify in bulk leaf samples. Consistent with this idea, most of the genes identified as differentially expressed in LT-treated vte2 have low expression levels and attempts to verify their expression by traditional RNA gel blot analysis often failed (data not shown). It is possible that differential transcriptional responses may only be present in transfer cells of vte2, where endomembrane biogenesis is strongly induced (Maeda et al., 2006) and the deposition of callose and abnormal cell wall ingrowths occur (Figure 6). Future experiments utilizing in situ hybridization or laser-microdissection of vascular parenchyma cells would be necessary to directly test whether more than the 77 genes identified in this study show such cell specific expression at LT and whether additional genes are regulated by tocopherols and also may contribute to the LT-induced phenotype of vte2.

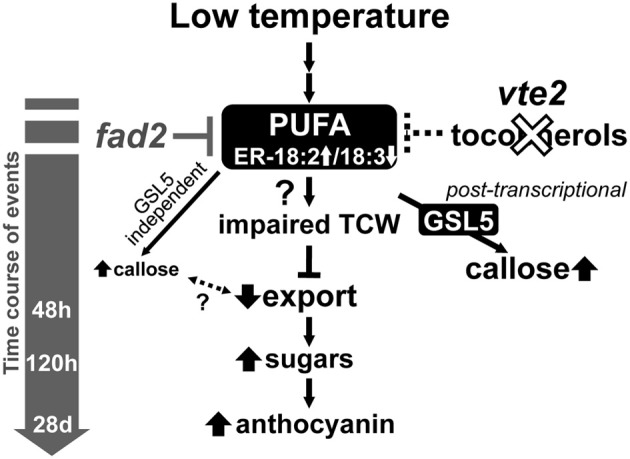

The biochemical phenotype of 48 h-LT-treated vte2 plants includes phloem transfer cell-specific callose deposition that spreads from the petiole to the upper part of the mature leaves and potentially impacts the capacity of source to sink photoassimilate transportation (Maeda et al., 2006). Consistent with these phenotypes, the expression of several genes (e.g., glycosyl transferases, glucanases) that are potentially involved in cell wall polymer modification in transfer cells (Dibley et al., 2009) were significantly upregulated in vte2 (Table 1). We also assessed the molecular nature of vasculature specific callose deposition observed in LT-treated vte2 and its impact on the photoassimilate export phenotype. Based on our microarray analysis GSL4 and GSL11 were more strongly upregulated in LT-treated vte2 than in Col (Supplemental Figure S5) and therefore considered likely candidates for enzymes mediating the massive callose deposition observed in LT-treated vte2. However, introduction of gsl4 and gsl11 mutations into the vte2 background did not visibly alter the callose deposition or overall phenotypes in LT-induced gsl4 vte2 or gsl11 vte2 double mutants (Figure 4). Somewhat surprisingly, though GSL5 was not differentially expressed in LT-treated vte2 and Col (Supplemental Figure S5), knocking out GSL5 in the vte2 background eliminated the majority, but not all, of callose deposition in LT-treated vte2 (Figures 5A and 7), indicating that the bulk of vte2 callose deposition at LT is GSL5-dependent (Figure 7). Because GSL5 is also responsible for callose deposition in response to wounding (Jacobs et al., 2003), tocopherol deficiency may improperly stimulate the wound response pathway in transfer cells and lead to post-transcriptional activation of the GSL5 enzyme in transfer cells. However, Col and vte2 showed similar levels of wound-induced callose deposition (data not shown). Taken together, these data suggest that tocopherols are required for post-transcriptional activation of GSL5 in transfer cells by a mechanism that is likely independent of the wound-signaling pathway.

Figure 7.

A proposed model of the timing of biochemical changes in LT-induced phenotypes of tocopherol-deficient mutants. Tocopherol deficiency, e.g., by the vte2 mutation, leads to constitutive alterations in the fatty acid composition of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane lipids [i.e., reduced linolenic acid (18:3) and increased linoleic acid (18:2)]. These alterations are suppressed by the mutation of the ER FATTY ACID DESATURASE 2 gene (fad2), which also suppresses all of the LT-induced vte2 phenotypes (Maeda et al., 2008; Song et al., 2010). Subsequent vasculature-specific callose deposition is primarily mediated by the GSL5 enzyme and tocopherol-deficiency affects its activity post-transcriptionally. Although low levels of GSL5-independent callose deposition still occurs, loss of the massive GSL5-dependent callose deposition in transfer cells does not affected the subsequent defect in photoassimilate export in LT-treated vte2.

Unexpectedly, elimination of the majority of LT-inducible callose deposition by introduction of the gsl5 mutation into the vte2 background did not impact any of the other vte2 LT phenotypes (Figure 5). The vte2 mutant develops an abnormally thickened TCW structure with fewer to no reticulate wall ingrowths (Figure 6; Maeda et al., 2006, 2008). These structural anomalies are still retained in vte2 gsl5 (Figure 6). Thus, although it can be argued that the weaker, GSL5-independent fluorescent signals observed in the vasculature of vte2 gsl5 may still impact photosynthate transport and development of the full suite of vte2 LT phenotypes (Figures 6A,C,E,G, 7), these results indicate that the absolute level of callose deposition in transfer cells does not correlate with the photoassimilate export phenotype of vte2. This suggests that GSL5-dependent callose deposition is an event independent or downstream of the impaired photoassimilate export in LT-treated vte2 (Figure 7). Future studies will focus on whether GSL5-independent callose deposition is involved in the impaired photoassimilate transportation phenotype by introducing additional gsl mutations into the vte2 gsl5 background (e.g., by constructing vte2 gsl5 gsl4 gsl11 quadruple mutant) to attempt elimination of all callose deposition in LT-treated vte2. Additional candidates to assess for this function include GSL8 and GSL12, which contribute to the control of symplastic trafficking through plasmodesmata (Guseman et al., 2010; Vaten et al., 2011).

Previous and current studies have demonstrated that tocopherols are required for normal development of TCW ingrowths in Arabidopsis leaves in response to LT (Figure 6; Maeda et al., 2006, 2008). Although the precise underlying mechanism remains elusive, suppressor mutant analyses (Maeda et al., 2008; Song et al., 2010) and our recent transorganellar complementation study (Mehrshahi et al., 2013) suggest that deficiency in plastid-localized tocopherols directly impacts ER membrane lipid biogenesis. Although speculative at this point, these alterations in ER membrane lipid metabolism may in turn impact other endomembrane-related processes, such as the massive increase in vesicular trafficking required for deposition of cell wall material in transfer cells at LT (Talbot et al., 2002; McCurdy et al., 2008). Further investigation of the molecular links between altered ER lipid metabolism and the impairment of TCW development in LT-treated vte2 (Figure 7) will illuminate the fundamental mechanisms underlying TCW development and function at LT.

Author contributions

Hiroshi Maeda, Wan Song, and Dean DellaPenna designed research; Hiroshi Maeda, Wan Song, and Tammy Sage performed research; Hiroshi Maeda, Wan Song, Tammy Sage, and Dean DellaPenna analyzed data; Hiroshi Maeda, Wan Song, and Dean DellaPenna wrote the paper.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Maria Magallanes-Lundback for performing RNA extraction and labeling and the Research Technology Support Facility (RTSF) at Michigan State University for performing microarray analysis. We thank Kathy Sault for technical assistance with microscopy and other members of the DellaPenna lab for their critical advice and discussions. This work was supported by NSF grant MCB-023529 to Dean DellaPenna and a Connaught Award and NSERC of Canada Discovery Grant to Tammy Sage.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://www.frontiersin.org/journal/10.3389/fpls.2014.00046/abstract

RNA degradation plot for the 18 microarrays.

QC plot of 3': 5' ratios for control genes, percentage of present gene calls, and background levels of 18 microarrays.

Box plots of all perfect match (PM) intensities of non-normalized (upper) and quantile normalized (bottom) 18 array data set.

Whole plant phenotypes of the gsl5 vte2 mutant grown under permissive conditions for 4 weeks.

Gene expression profiles for the 12 GSL family members in 4-week old Col and vte2 treated at LT for 0, 48, and 120 h.

References

- Barella L., Muller P. Y., Schlachter M., Hunziker W., Stocklin E., Spitzer V., et al. (2004). Identification of hepatic molecular mechanisms of action of alpha-tocopherol using global gene expression profile analysis in rats. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 1689, 66–74 10.1016/j.bbadis.2004.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y., Hochberg Y. (1995). Controlling the false discovery rate - a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. B Methodol. 57, 289–300 [Google Scholar]

- Bolstad B. M., Irizarry R. A., Astrand M., Speed T. P. (2003). A comparison of normalization methods for high density oligonucleotide array data based on variance and bias. Bioinformatics 19, 185–193 10.1093/bioinformatics/19.2.185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bramley P. M., Elmadfa I., Kafatos A., Kelly F. J., Manios Y., Roxborough H. E., et al. (2000). Vitamin E. J. Sci. Food Agric. 80, 913–938 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burton G. W., Ingold K. U. (1981). Autoxidation of biological molecules. 1. The antioxidant activity of vitamin E and related chain-breaking phenolic antioxidants in vitro. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 103, 6472–6477 10.1021/ja00411a035 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Collakova E., DellaPenna D. (2001). Isolation and functional analysis of homogentisate phytyltransferase from Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 and Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 127, 1113–1124 10.1104/pp.010421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collakova E., DellaPenna D. (2003). The role of homogentisate phytyltransferase and other tocopherol pathway enzymes in the regulation of tocopherol synthesis during abiotic stress. Plant Physiol. 133, 930–940 10.1104/pp.103.026138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DellaPenna D., Mene-Saffrane L. (2011). Vitamin E, in Advances in Botanical Research, eds Rebeille F., Douces R. (Amsterdam: Elsevier Inc.), 179–227 [Google Scholar]

- Dibley S. J., Zhou Y. C., Andriunas F. A., Talbot M. J., Offler C. E., Patrick J. W., et al. (2009). Early gene expression programs accompanying trans-differentiation of epidermal cells of Vicia faba cotyledons into transfer cells. New Phytol. 182, 863–877 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.02822.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckeykaltenbach H., Ernst D., Heller W., Sandermann H. (1994). Biochemical-plant responses to ozone. 4. Cross-induction of defensive pathways in parsley (Petroselinum crispum L.) plants. Plant Physiol. 104, 67–74 10.1104/pp.104.1.67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erin A. N., Spirin M. M., Tabidze L. V., Kagan V. E. (1984). Formation of alpha-tocopherol complexes with fatty acids - a hypothetical mechanism of stabilization of biomembranes by vitamin E. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 774, 96–102 10.1016/0005-2736(84)90279-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans H. M., Bishop K. S. (1922). On the existence of a hitherto unrecognized dietary factor essential for reproduction. Science 56, 650–651 10.1126/science.56.1458.650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahrenholtz S. R., Doleiden F. H., Trozzolo A. M., Lamola A. A. (1974). Quenching of singlet oxygen by alpha-tocopherol. Photochem. Photobiol. 20, 505–509 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1974.tb06610.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falcone D. L., Gibson S., Lemieux B., Somerville C. (1994). Identification of a gene that complements an Arabidopsis mutant deficient in chloroplast omega-6 desaturase activity. Plant Physiol. 106, 1453–1459 10.1104/pp.106.4.1453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson S., Arondel V., Iba K., Somerville C. (1994). Cloning of a temperature-regulated gene encoding a chloroplast omega-3 desaturase from Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Physiol. 106, 1615–1621 10.1104/pp.106.4.1615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gohil K., Schock B. C., Chakraborty A. A., Terasawa Y., Raber J., Farese R. V., et al. (2003). Gene expression profile of oxidant stress and neurodegeneration in transgenic mice deficient in alpha-tocopherol transfer protein. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 35, 1343–1354 10.1016/S0891-5849(03)00509-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guseman J. M., Lee J. S., Bogenschutz N. L., Peterson K. M., Virata R. E., Xie B., et al. (2010). Dysregulation of cell-to-cell connectivity and stomatal patterning by loss-of-function mutation in Arabidopsis chorus (glucan synthase-like 8). Development 137, 1731–1741 10.1242/dev.049197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haritatos E., Medville R., Turgeon R. (2000). Minor vein structure and sugar transport in Arabidopsis thaliana. Planta 211, 105–111 10.1007/s004250000268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heppard E. P., Kinney A. J., Stecca K. L., Miao G. H. (1996). Developmental and growth temperature regulation of two different microsomal omega-6 desaturase genes in soybeans. Plant Physiol. 110, 311–319 10.1104/pp.110.1.311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofius D., Hajirezaei M. R., Geiger M., Tschiersch H., Melzer M., Sonnewald U. (2004). RNAi-mediated tocopherol deficiency impairs photoassimilate export in transgenic potato plants. Plant Physiol. 135, 1256–1268 10.1104/pp.104.043927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohnjec N., Lenz F., Fehlberg V., Vieweg M. F., Baier M. C., Hause B., et al. (2009). The signal peptide of the Medicago truncatula modular nodulin MtNOD25 operates as an address label for the specific targeting of proteins to nitrogen-fixing symbiosomes. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 22, 63–72 10.1094/MPMI-22-1-0063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong Z. L., Delauney A. J., Verma D. P. S. (2001). A cell plate specific callose synthase and its interaction with phragmoplastin. Plant Cell 13, 755–768 10.1105/tpc.13.4.755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyland S., Muller D., Hayton S., Stoecklin E., Barella L. (2006). Cortical gene expression in the vitamin E-deficient rat: possible mechanisms for the electrophysiological abnormalities of visual and neural function. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 50, 433–441 10.1159/000094635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iba K., Gibson S., Nishiuchi T., Fuse T., Nishimura M., Arondel V., et al. (1993). A gene encoding a chloroplast omega-3 fatty acid desaturase complements alterations in fatty acid desaturation and chloroplast copy number of the fad7 mutant of Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Biol. Chem. 268, 24099–24105 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irizarry R. A., Bolstad B. M., Collin F., Cope L. M., Hobbs B., Speed T. P. (2003). Summaries of affymetrix GeneChip probe level data. Nucleic Acids Res. 31:e15 10.1093/nar/gng015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs A. K., Lipka V., Burton R. A., Panstruga R., Strizhov N., Schulze-Lefert P., et al. (2003). An Arabidopsis callose synthase, GSL5, is required for wound and papillary callose formation. Plant Cell 15, 2503–2513 10.1105/tpc.016097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jervis K. M., Robaire B. (2004). The effects of long-term vitamin E treatment on gene expression and oxidative stress damage in the aging brown Norway rat epididymis. Biol. Reprod. 71, 1088–1095 10.1095/biolreprod.104.028886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagan V. E. (1989). Tocopherol stabilizes membrane against phospholipase a, free fatty acids, and lysophospholipids. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 570, 121–135 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1989.tb14913.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamal-Eldin A., Appelqvist L. A. (1996). The chemistry and antioxidant properties of tocopherols and tocotrienols. Lipids 31, 671–701 10.1007/BF02522884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kangasjarvi J., Talvinen J., Utriainen M., Katjalainen R. (1994). Plant defence systems induced by ozone. Plant Cell Environ. 17, 783–794 10.1111/j.1365-3040.1994.tb00173.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liebler D. C., Burr J. A. (1992). Oxidation of vitamin E during iron-catalyzed lipid-peroxidation - evidence for electron-transfer reactions of the tocopheroxyl radical. Biochemistry 31, 8278–8284 10.1021/bi00150a022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwikow A., Gallois P., Sadowski J. (2004). Ozone-induced oxidative stress response in Arabidopsis: transcription profiling by microarray approach. Cell. Mol. Biol. Lett. 9, 829–842 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda H., Sage T. L., Isaac G., Welti R., DellaPenna D. (2008). Tocopherols modulate extraplastidic polyunsaturated fatty acid metabolism in Arabidopsis at low temperature. Plant Cell 20, 452–470 10.1105/tpc.107.054718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda H., Song W., Sage T. L., DellaPenna D. (2006). Tocopherols play a crucial role in low-temperature adaptation and phloem loading in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 18, 2710–2732 10.1105/tpc.105.039404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCurdy D. W., Patrick J. W., Offler C. (2008). Wall ingrowth formation in transfer cells: novel examples of localized wall deposition in plant cells. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 653–661 10.1016/j.pbi.2008.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehrshahi P., Stefano G., Andaloro J. M., Brandizzi F., Froehlich J. E., DellaPenna D. (2013). Transorganellar complementation redefines the biochemical continuity of endoplasmic reticulum and chloroplasts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 12126–12131 10.1073/pnas.1306331110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mene-Saffrane L., Jones A. D., DellaPenna D. (2010). Plastochromanol-8 and tocopherols are essential lipid-soluble antioxidants during seed desiccation and quiescence in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 17815–17820 10.1073/pnas.1006971107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nell S., Bahtz R., Bossecker A., Kipp A., Landes N., Bumke-Vogt C., et al. (2007). PCR-verified microarray analysis and functional in vitro studies indicate a role of alpha-tocopherol in vesicular transport. Free Radic. Res. 41, 930–942 10.1080/10715760701416988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura M. T., Stein M., Hou B. H., Vogel J. P., Edwards H., Somerville S. C. (2003). Loss of a callose synthase results in salicylic acid-dependent disease resistance. Science 301, 969–972 10.1126/science.1086716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuley J., Lightner J., Feldmann K., Yadav N., Lark E., Browse J. (1994). Arabidopsis FAD2 gene encodes the enzyme that is essential for polyunsaturated lipid synthesis. Plant Cell 6, 147–158 10.1105/tpc.6.1.147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oommen S., Vasu V. T., Leonard S. W., Traber M. G., Cross C. E., Gohil K. (2007). Genome wide responses of murine lungs to dietary alpha-tocopherol. Free Radic. Res. 41, 98–109 10.1080/10715760600935567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Provencher L. M., Miao L., Sinha N., Lucas W. J. (2001). Sucrose export defective1 encodes a novel protein implicated in chloroplast-to-nucleus signaling. Plant Cell 13, 1127–1141 10.1105/tpc.13.5.1127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richmond T. A., Somerville C. R. (2000). The cellulose synthase superfamily. Plant Physiol. 124, 495–498 10.1104/pp.124.2.495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rota C., Barella L., Minihane A. M., Stocklin E., Rimbach G. (2004). Dietary alpha-tocopherol affects differential gene expression in rat testes. IUBMB Life 56, 277–280 10.1080/15216540410001724133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rota C., Rimbach G., Minihane A. M., Stoecklin E., Barella L. (2005). Dietary vitamin E modulates differential gene expression in the rat hippocampus: potential implications for its neuroprotective properties. Nutr. Neurosci. 8, 21–29 10.1080/10284150400027123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russin W. A., Evert R. F., Vanderveer P. J., Sharkey T. D., Briggs S. P. (1996). Modification of a specific class of plasmodesmata and loss of sucrose export ability in the sucrose export defective1 maize mutant. Plant Cell 8, 645–658 10.1105/tpc.8.4.645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sattler S. E., Cahoon E. B., Coughlan S. J., DellaPenna D. (2003). Characterization of tocopherol cyclases from higher plants and cyanobacteria. Evolutionary implications for tocopherol synthesis and function. Plant Physiol. 132, 2184–2195 10.1104/pp.103.024257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sattler S. E., Gilliland L. U., Magallanes-Lundback M., Pollard M., DellaPenna D. (2004). Vitamin E is essential for seed longevity, and for preventing lipid peroxidation during germination. Plant Cell 16, 1419–1432 10.1105/tpc.021360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sattler S. E., Mene-Saffrane L., Farmer E. E., Krischke M., Mueller M. J., DellaPenna D. (2006). Nonenzymatic lipid peroxidation reprograms gene expression and activates defense markers in Arabidopsis tocopherol-deficient mutants. Plant Cell 18, 3706–3720 10.1105/tpc.106.044065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savidge B., Weiss J. D., Wong Y. H. H., Lassner M. W., Mitsky T. A., Shewmaker C. K., et al. (2002). Isolation and characterization of homogentisate phytyltransferase genes from Synechocystis sp PCC 6803 and Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 129, 321–332 10.1104/pp.010747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider C. (2005). Chemistry and biology of vitamin E. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 49, 7–30 10.1002/mnfr.200400049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyth G. K. (2005). Limma: linear models for microarray data, in Bioinformatics and Computational Biology Solutions Using R and Bioconductor, eds Gentlemen V. C. R., Dudoit S., Irizarry R., Huber W. (New York, NY: Springer; ), 397–420 10.1007/0-387-29362-0_23 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Song W., Maeda H., DellaPenna D. (2010). Mutations of the ER to plastid lipid transporters TGD1, 2, 3 and 4 and the ER oleate desaturase FAD2 suppress the low temperature-induced phenotype of Arabidopsis tocopherol-deficient mutant vte2. Plant J. 62, 1004–1018 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04212.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stillwell W., Dallman T., Dumaual A. C., Crump F. T., Jenski L. J. (1996). Cholesterol versus alpha-tocopherol: effects on properties of bilayers made from heteroacid phosphatidylcholines. Biochemistry 35, 13353–13362 10.1021/bi961058m [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talbot M. J., Offler C. E., McCurdy D. W. (2002). Transfer cell wall architecture: a contribution towards understanding localized wall deposition. Protoplasma 219, 197–209 10.1007/s007090200021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tappel A. L. (1972). Vitamin E and free radical peroxidation of lipids. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 203, 12–28 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1972.tb27851.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandewiel C., Norris J. H., Bochenek B., Dickstein R., Bisseling T., Hirsch A. M. (1990). Nodulin gene expression and Enod2 Localization in effective, nitrogen-fixing and ineffective, bacteria-free nodules of alfalfa. Plant Cell 2, 1009–1017 10.1105/tpc.2.10.1009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasu V. T., Hobson B., Gohil K., Cross C. E. (2007). Genome-wide screening of alpha-tocopherol sensitive genes in heart tissue from alpha-tocopherol transfer protein null mice (ATTP(-/-)). FEBS Lett. 581, 1572–1578 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.03.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasu V. T., Ott S., Hobson B., Rashidi V., Oommen S., Cross C. E., et al. (2009). Sarcolipin and ubiquitin carboxy-terminal hydrolase 1 mRNAs are over-expressed in skeletal muscles of alpha-tocopherol deficient mice. Free Radic. Res. 43, 106–116 10.1080/10715760802616676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaten A., Dettmer J., Wu S., Stierhof Y. D., Miyashima S., Yadav S. R., et al. (2011). Callose biosynthesis regulates symplastic trafficking during root development. Dev. Cell 21, 1144–1155 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X. Y., Quinn P. J. (2000). The location and function of vitamin E in membranes (review). Mol. Membr. Biol. 17, 143–156 10.1080/09687680010000311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zavaliev R., Ueki S., Epel B. L., Citovsky V. (2011). Biology of callose (beta-1,3-glucan) turnover at plasmodesmata. Protoplasma 248, 117–130 10.1007/s00709-010-0247-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann P., Hirsch-Hoffmann M., Hennig L., Gruissem W. (2004). GENEVESTIGATOR. Arabidopsis microarray database and analysis toolbox. Plant Physiol. 136, 2621–2632 10.1104/pp.104.046367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

RNA degradation plot for the 18 microarrays.

QC plot of 3': 5' ratios for control genes, percentage of present gene calls, and background levels of 18 microarrays.

Box plots of all perfect match (PM) intensities of non-normalized (upper) and quantile normalized (bottom) 18 array data set.

Whole plant phenotypes of the gsl5 vte2 mutant grown under permissive conditions for 4 weeks.

Gene expression profiles for the 12 GSL family members in 4-week old Col and vte2 treated at LT for 0, 48, and 120 h.