Abstract

A composite containing cellulose (CEL) and chitosan (CS) synthesized by a simple and recyclable method by using butylmethylimmidazolium chloride, an ionic liquid, was found to exhibit remarkable enantiomeric selectivity toward adsorption of amino acids. 100%CS shows the highest adsorption capacity and enantiomeric selectivity. A racemic amino acid can be enantiomerically resolved by 100%CS in about 96–120 hrs. Interestingly, adsorption by 50:50 CEL:CS is more similar to that by 100%CS than to 100%CEL. Specifically, while 100% CEL shows lowest adsorption capacity and enantiomeric selectivity, 50:50 CEL:CS has sufficient enantiomeric selectivity to enable it to be used for chiral resolution. This is very significant because in spite of its high enantiomeric selectivity, 100%CS cannot practically be used because it has relatively poor mechanical properties and undergoes extensive swelling. Adding 50% of CEL to CS substantially improves the mechanic properties and reduces its swelling while retains sufficient enantiomeric selectivity to enable it to be used for routine chiral separations. Kinetic results indicate that the enantiomeric selective adsorption is due not to the initial surface adsorption but rather to the subsequent stage in which the adsorbate molecules diffuse into the pores within the particle of the composites and consequently got adsorbed by the interior of each particle. The strong inter- and intramolecular hydrogen bond network in CEL enables it to adopt a very dense structure which makes it difficult for adsorbate molecules to diffuse to its interior thereby leading to low enantiomeric selectivity. Compared to hydroxy group, amino group cannot form strong hydrogen bond. The hydrogen bond network in CS is not as extensive as in CEL, and its inner structure is relatively less dense than CEL. Adsorbate molecules can, therefore, diffuse from the outer surface to its inner structure relatively easier than in CEL, thereby leading to higher enantiomeric selectivity for 100%CS.

INTRODUCTION

Differences between the physiological properties and the therapeutic effects of the enantiomeric forms of many compounds have been recognized for some time1–4. Very often, only one form of an enantiomeric pair is pharmacologically active. The other or others can reverse or otherwise limit the effect of the desired enantiomer. However, despite this knowledge, only 61 of the 528 chiral synthetic drugs are marketed as single enantiomers while the other 467 are sold as racemates.1 Recognizing the importance of chiral effects, the FDA in 1992 issued a mandate requiring pharmaceutical companies to evaluate the effects of individual enantiomers and to verify the enantiomeric purity of chiral drugs that are produced1–4. It is thus hardly surprising that the pharmaceutical industry needs effective methods for optical resolution of racemic mixtures in preparative scale. Conventional chiral resolution methods, including preferential crystallization, stereoselective transformation by an optical resolution agent, high performance liquid chromatography and electrophoresis, have the common shortcomings such as relatively low productivity, expensive chemical consumables, and high energy consumption.8–10 The use of membrane technology for chiral separations offers several advantages over traditional methods, including low time cost, simplicity of operation, and easy scale-up.5–10 Furthermore, when using chiral activated membranes only a small quantity of an expensive chiral selector is required.8–10

Polysaccharides are chiral polymers that can potentially be used as chiral membrane for enantiomeric separations. Chitosan (CS) and cellulose (CEL) are two of the most widely used polysaccharides. Chitosan (CS) is a linear amino polysaccharide, obtained by N-deacetylation of chitin, and chitin is the second most abundant naturally occurring polysaccharide after cellulose (CEL).11–14 CS structure allows it to have some unique properties including antimicrobial, drug delivery, wound healing, hemostasis and pollutant adsorbant.12–32 In addition, CS is also biocompatible and biodegradable. Unfortunately, in spite of its potentials, there are drawbacks which severely limit applications of CS. For example similar to cellulose (CEL), the most abundant substance on earth, in CS, a network of intra- and inter-hydrogen bonds enables it to adopt an ordered structure.15–22 While such structure is responsible for CS to have aforementioned properties and CEL to have superior mechanical strength, it also makes them insoluble in most solvents.15–22 As a consequence, high temperature and strong exotic solvents, and strong acid followed by neutralization with base are needed to dissolve CEL and CS, respectively. These methods are undesirable because they are based on the use of corrosive and volatile solvents, require high temperature and suffer from side reactions and impurities which may lead to changes in structure and properties of the polysaccharides. More importantly, it is not possible to use a single solvent or system of solvents to dissolve both CEL and CS. Furthermore, CS is known to swell in water which leads to structural weakening in wet environments.15–22 To increase the structural strength of CS products, attempts have been made to covalently bind or graft CS onto man-made polymers to strengthen its structure [9–29]. Such modification is not desirable because it may inadvertently alter CS properties, making it not biocompatible and toxic and lessening or removing its unique properties. A new method which can effectively dissolve both CS and CEL not at high temperature and not by corrosive and volatile solvents but rather by recyclable “green” solvent is particularly needed.

We have demonstrated recently that a simple ionic liquid, BMIm+Cl−, can dissolve both CEL and CS, and by use of this BMIm+Cl− as the sole solvent, we developed a simple, GREEN and totally recyclable method to synthesize [CEL+CS] composites just by dissolution without using any chemical modifications or reactions.23–25 The [CEL+CS] composite obtained was found to be not only biodegradable and biocompatible but also retain unique properties of its component, namely superior mechanical strength (from CEL) and excellent antibacterial and adsorption capability for pollutants and toxins (from CS).23–25

Since the [CEL+CS] composite was synthesized without employing any chemical modifications, the chirality nature of its components remain intact, it is possible that it may be used as chiral membrane for enantiomeric separation of racemic mixtures. Such considerations prompted us to initiate this study which aims to hasten the breakthrough by using the [CEL+CS] composite synthesized by the green and recyclable method which we have developed recently, for chiral separation. Results on enantiomeric differentiation on the adsorption of different amino acids by the [CEL+CS] composite and mechanism of the chiral adsorption deduced from adsorption kinetics of composites having different concentration of CEL and CS will be reported herein.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

The polysaccharide composite materials used in this study were prepared according to procedures previously developed in our laboratory.23–25 D- and L-enantiomers (99%) of tryptophan (Trp), tyrosine (Tyr), histidine (His) and phenylalanine (Phe) were obtained from Alfa Aesar. Experiments with racemic mixtures were carried out on a Shimadzu LC-20AT prominence Liquid Chromatograph equipped with a SPD-20A prominence UV/Vis detector. The chiral column used was a 250 L × 4.6 mm ID 5-μm particles stainless steel column (Advance Separation Technologies, Whippany, NJ, Chirobiotic TAG column. The mobile phase for Trp, Tyr and Phe was 60:40 methanol/water while His was separated using 30:70 ethanol/water in 160mM sodium phosphate buffer adjusted to pH 4.5, and the flow rate was 1.0mL/min. Trp and Tyr were detected at 275nm, and His and Phe were detected at 205nm. Experiments with optically active (pure enantiomers) samples were carried out on a Perkin Elmer Lambda 35 UV/Visible spectrometer.

For the enantiomeric resolution experiments, about 0.3g of the dry polysaccharide composite material was placed in a sample vial. 30mL of 1.0×10−3M DL racemic solution of the amino acid was added (concentration of both the D and the L enantiomers in this solution was 5.0×10−4M). The amino acid solutions were prepared in distilled de-ionized water at pH 6.6. The vials were tightly closed and agitated (at room temperature) at 240 osc/min on a mechanical shaker (Model E6005 Explosion Proof Reciprocal Shaker, Eberbach Corporation, Ann Arbor, MI). At specific time intervals, 20KL solutions were withdrawn and injected into the HPLC for analysis. It is possible that for racemic mixture, the presence of one enantiomer may have some effect on the adsorption of other enantiomer. To determine if such an effect is present the adsorption of optically active (pure enantiomers) D and L enantiomers was measured separately by UV-vis spectrophometer. The experimental set-up and conditions (mass of film and volume of solution) was the same as those used for the racemic mixture. The concentration of the optically active solutions used for this experiment was 5.0×10−4M. This concentration is the same as that of the individual enantiomers used for the racemic experiment described above. In addition, since these were solutions of pure enantiomers, the residual concentration of the enantiomer in solution at specific time intervals was directly determined by UV-vis absorption. After measuring the UV absorption of the solution, the sample solution was returned to its sample vial to ensure that there were no significant volume changes of the sample during the course of the experiment.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

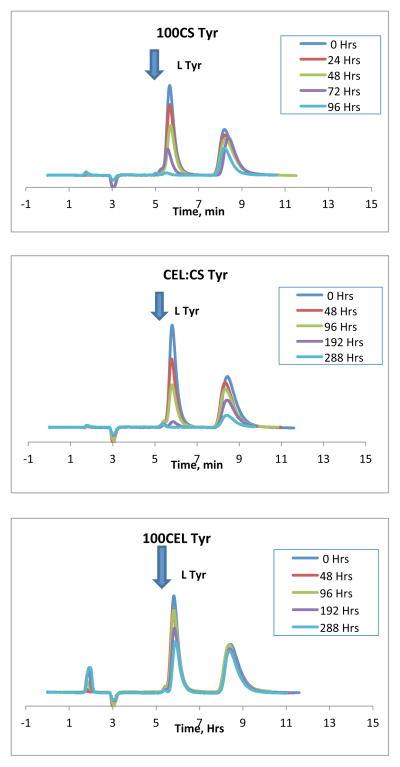

HPLC chiral separation was carried out to determine adsorption of D and L-Tyr enantiomers from a solution of 1.0×10−3M racemic mixture using the 3 different polysaccharide composite materials: 100%CS, [CEL+CS] and 100%CEL. Obtained chromatograms are shown in Figure 1. As expected, the HPLC chromatograms contain two bands corresponding to the two enantiomers in solution (D and L). The identity of each band was determined by spiking the racemic solutions with one of the enantiomers and identifying the band whose intensity increased as corresponding to that of the enantiomer in the spike. In all cases, the L enantiomer was eluted first (this band is indicated by an arrow in Figure 1). The second unlabeled band corresponds to the D enantiomer. The intensity of the two bands was found to decrease with time. However, as indicated by the arrow in the Figure, the intensity of the L enantiomer decreases relatively faster than that of the D enantiomer. For the 100%CS composite, the band for the L enantiomer decreases and disappears completely after about 96 hrs while the band for the D enantiomer had only changed slightly. For the [CEL+CS] composite, it required about 288 hrs for the band of the L enantiomer to disappear. For the 100%CEL composite, both bands were still present in the chromatograms even after 288 hrs. However, even though both bands were still present, the intensity of the L-enantiomer band has decreased more than that of the D enantiomer. Similar results were also found for Trp, His and Phe. The results seem to suggest that these polysaccharide composite materials selectvively adsorb more of the L enantiomer than of the D enantiomer. Such selective adsorption of one enantiomer over the other can lead to enrichment of the racemic mixtures which potentially could be used for enantiomeric resolution. Results also indicate that the rate at which the intensity of the L band decreases seem to be dependent on the polysaccharide composite used. For example, it took about 96 hrs for the L band to disappear with the 100%CS composite whereas the [CEL+CS] composite required about 288 hrs. For the 100%CEL, both HPLC bands were still present even after 288 hrs.

Figure 1.

HPLC chromatograms for the sorption of D and L Tyr on to the different polysaccharide composites

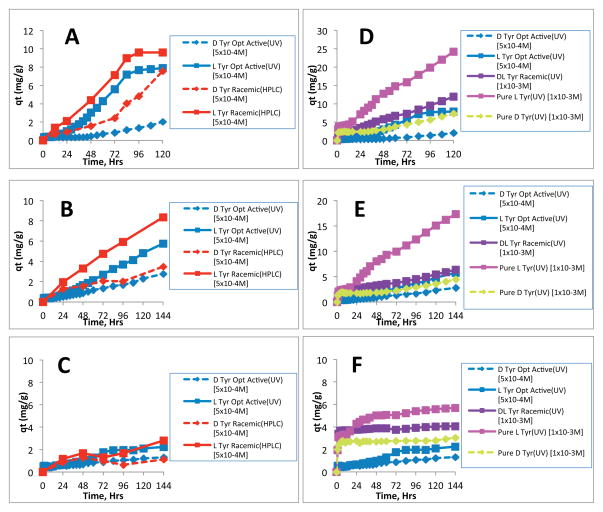

These HPLC results were then used to calculate the solution concentration of each enantiomer at each measurement time point. The change in solution concentration with time for the three polysaccharide composites is shown in Figure 2A. This figure also illustrates what was observed with the chromatograms where the solution concentrations of the enantiomers is decreasing with time. Also, for each of the three composites, the solution concentration of the L enantiomer (squares, solid line) was found to decrease faster than that of the D enantiomer (diamond, dashed line). From these HPLC results, the amount of each enantiomer that has been adsorbed onto the composite material can be calculated using the following mass balance equation:

| (1) |

where qt (mg/g) is the amount of enantiomer adsorbed at any given time, t, Ci and Ct (mg/L) are the initial and at time t of solution concentration of the enantiomer, respectively. V (L) is the volume of the solution and m (g) is the weight of the composite material. Typical results for the adsorption of D and L Tyr form of a racemic mixture by all three composite materials are shown in Figure 2B. Essentially, these results show similar information which is depicted in Figure 2A, namely, the amount of L enantiomer adsorbed onto the composite material is higher than that of the D enantiomer. For both L and D enantiomers, the order of adsorption capacity for the composites as explained earlier was found to be 100%CS > [CEL+CS] > 100%CEL. This finding was not unexpected as CS is generally known to be a good adsorbent. The purpose of adding CEL into CS is, as explained before and verified in our previous publication, to improve the poor mechanical and rheological properties of CS.23–25 The results in Figure 2B show that after about 96 hrs, 100CS had adsorbed about 5.7 times more L enantiomer than 100%CEL. Interestingly, even though the adsorption of the L enantiomer by the [CEL+CS] composite is expectedly lower than that of the 100%CS, it is still about 3.5 times higher than that of the 100%CEL composite material. This adsorption performance is still relatively high considering the improvement in mechanical and rheological properties that is gained by adding 50% CEL into CS. Specifically, as described in our previous publication, while the tensile strength of the 50:50 CEL:CS composite material is 2X higher than that of the 100%CS, the swelling in water of the former is only about 1.2 times less than that of the 100CS material.37 These observations clearly indicate that stronger, more stable and effective enantiomeric selective polysaccharide composite materials can be fabricated by judiciously control compositions and concentration of the CEL:CS composite.

Figure 2.

A) Change in solution concentration with time for a Tyr racemic solution and B) Adsorption of different Tyr enantiomers by the different composites.

It is possible that for racemic mixture, the presence of one enantiomer may have some effect on the adsorption of other enantiomer. To determine if such an effect is present the adsorption of optically active (pure enantiomers) D and L enantiomers was measured separately by UV-vis spectrophometer. The experimental set-up and conditions (mass of film and volume of solution) was the same as those used for the racemic mixture. The concentration of the optically active amino acid solutions used for this experiment was 5.0×10−4M which is the same as that of the individual enantiomers used for the HPLC racemic experiment described above

The results obtained for the adsorption of Tyr enantiomers by all three polysaccharide composite materials, determined by UV-vis, are plotted together with the HPLC results for the racemic experiment (Figure 3). The concentration of each enantiomer in the solution at the beginning of the experiment and the method used for the measurement (HPLC or UV) are indicated in the figure legend. The plots on the left side of the figure are a comparison of the HPLC method and the UV method (Figs 3A, B and C). It can be seen from this figure that for both methods, the adsorption of the L enantiomer is higher than that of the D enantiomer. The results of the UV method in this figure further confirm that the adsorption of the L enantiomer is selectively favored, even when the enantiomers are measured separately (optically active solutions). However, it can also be observed from this figure that the rate of adsorption of the enantiomers from racemic solutions (HPLC) is different from that of adsorption from optically active solutions (UV). It should be noted, however, that the total amino acid concentration in these two experiments was not the same. The HPLC racemic experiment was performed with a total concentration of 1.0×10−3M (i.e., 5.0×10−4M for each enantiomer). Conversely, the concentration used in the UV experiment for the pure enantiomers was 5.0×10−4M. Since adsorption capacity is known to be dependent on the type and concentration of chemicals present in the solution, the differences in the type (racemic mixture compared to optically active compounds) and concentration of the amino acid in these two experimental methods may be responsible for the observed differences in the adsorption profiles for the two methods. Nevertheless, additional experiments were then carried out under different conditions to gain more insight into the processes governing the adsorption and ultimately the resolution of the amino acid enantiomers. The results of these experiments are shown in the plots on the right side of Figure 3, i.e., 3D, E and F.

Figure 3.

Sorption of D and L Tyr enantiomers from different solutions using (A and D) 100%CS (A), (B and E) [CEL+CS] composite; and (C and F) 100CEL composite.

As expected, the adsorption of both D and L enantiomers exhibits dependency not only on the type (ie., optically active or racemic mixture) but also on the concentration of the amino acid present in solution. For example, in the adsorption of D Tyr (Figure 3D, the right plot), the adsorption profile of D Tyr in which the initial concentration was 1.0×10−3M (yellow diamond plot) is nearly twice as high as the sorption profile where the initial concentration was 5.0×10−4M (blue diamond plot). Similarly, the adsorption profile of L Tyr with an initial concentration of 1.0×10−3M (pink square plot) is also twice as high as the sorption profile where the initial concentration was 5.0×10−4M (blue square plot). However, when the adsorption experiment was done with two samples of the same total concentration but with different enantiomeric composition, i.e. 1.0×10−3M DL Tyr racemic mixture (purple square plot) and 1.0×10−3M pure optically active L solution (pink square plot), interesting adsorption profiles were observed. The adsorption profile of the pure L enantiomer solution was found to be nearly twice as high as that of the DL racemic solution. Since the total amino acid concentration of these two solutions is the same, the observed differences in the adsorption profiles is clearly due to the difference in the enantiomeric composition of the solutions. The solution that gave the highest adsorption profile is that of the pure optically active L solution. The relatively lower adsorptivity observed for the DL racemic mixture can be explained using results previously obtained with HPLC measurements. Specifically, in the HPLC experiments of the racemic mixtures, adsorption is favor the L-Tyr component of the DL-Tyr solution and not much of the D Tyr component is adsorbed. Since the concentration of the L Tyr component in this racemic solution is only half (5.0×10−4M) of that in the pure L (1.0×10−3M), the adsorption profile of the entire racemic solution equal adsorption of L-Tyr (i.e., QL-Tyr) + QD-Tyr where QL-Tyr is much higher than QD-Tyr. As a consequence, adsorption of the racemic mixture is relatively lower than the adsorption by 1.0×10−3M of pure optically active L-Tyr. These results are further confirmed by the observation that the adsorption profiles of 1.0×10−3M DL racemic solution (purple square plot) and 5.0×10−4 M pure L solution (blue square plot) are almost the same. As shown in Figure 3A and D, and 3B and E, similar results were observed for both 100%CS and [CEL+CS] composites, respectively while the trend for the 100CEL material (Figure 3C and F) was not as obvious due to the low adsorption capacity of this material.

Additional experiments were also carried on adsorption by all three composites (100CS, CEL:CS and 100CEL) of Tyr with the same total concentration but different enantiomeric compositions, namely, a 1.0×10−3 M solution which contains 6.67×10−4 M L-Tyr and 3.33×10−4M D-Try (on HPLC), 1.0×10−3 M of pure L-Try and1.0×10−3 M of DL-Try as well as 6.67×10−4M L-Tyr (on UV-vis). Results obtained are plotted together with those previously plotted in Figure 3A–F (for 5.0×10−4M of pure L- or pure D-Try and 1.0×10−3M of DL-Tyr) in Figure SI A, B, C of the Supporting Information. Again these results are in agreement with those presented in Figure 3, and further confirm conclusion described in previous paragraph, namely, all three 100CS, CEL:CS and 100CEL composites can enantiomerically adsorb the amino acids, and the adsorption is more favor of the L enantiomer than the D-enantiomer.

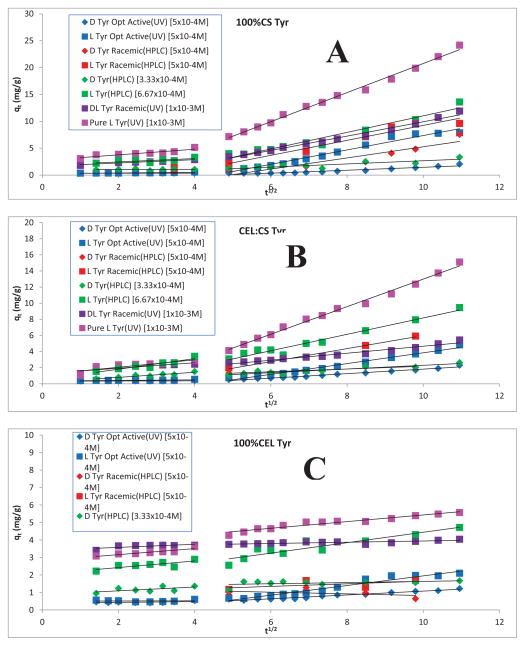

Additional information on adsorption mechanism can be gained by fitting experimental data to Weber’s intraparticle diffusion model.26–29 The intra-particle diffusion equation is given as follows26–29

| (2) |

where ki (mg g−1 min−0.5) is the intra-particle diffusion rate constant and I (mg g−1) is a constant that gives the information regarding the thickness of the boundary layer.26–29 Shown in figure 4 are representative intra-particle pore diffusion plots (qt versus t1/2) for different Tyr samples adsorbed on (A)100%CS, (B) 50:50 CS:CEL and (C)100%CEL. It is evident from the figure that there are two separate stages for all Tyr samples on all three composites. In the first linear portion (Stage I), the adsorbate molecules (in this case, Tyr molecules) were transported from solution through the solution/composite interface and characterized by kip1. This can be attributed to the immediate utilization of the most readily available adsorbing sites on surfaces of the composites 26–29. The first stage is followed by a second linear portion in which the adsorbate molecules diffuse into the pores within the particle of the composites and consequently got adsorbed by the interior of each particle which is measured by kip2.26–29 Table 1 lists values of kip1 and kip2, for adsorption of different Tyr samples by 100%CS, 50:50 CS:CEL and 100%CEL composite materials. (Similar values for His and Trp are listed in Table 2 and 3, respectively). Interestingly, it was found that kip2 is much larger than kip1 (from 6X to 14X) when Tyr molecules were adsorbed by 100% CS. When 50% of CEL was added to CS (i.e, 50:50 CS:CEL composite), kip2 is still larger than kip1 but the difference is much smaller than that by 100% CS composite (0.8X and 7.7X compared to 6X and 10X). However, in the absence of CS (i.e., 100%CEL composite) kip2 is either smaller than or within experimental error equal to kip1. These results may be explained by the differences in the structure of CS and CEL. It is a well-known fact that the strong inter- and intramolecular hydrogen bond network in CEL enables it to adopt a strong and very dense structure which makes it difficult for adsorbate molecules to diffuse from its surface to interior thereby leading to relatively low kip2 values. Compared to hydroxy group, amino group cannot form strong hydrogen bond. The hydrogen bond network in CS is, therefore, not as extensive as in CEL. As a consequence, the inner structure of CS is relatively less dense than CEL. Tyr molecules can, therefore, diffuse from the outer surface to its inner structure relatively easier than that in CEL. kip2 values are, therefore, much larger than kip1 as well as kip2 for CEL (since kip2 ~ kip1 for CEL). It is evident from Figure 4 and Table 1 that in all Tyr samples and for all three composites, kip1 is, within experimental error, the same for both enantiomers of L-Tyr whereas kip2 for L-Tyr is always higher than that for D-Tyr sample. The differences are, as expected, largest for 100%CS and smallest for 100%CEL. The results suggest that the enantiomeric selective adsorption is due mainly to the differences not in kip1 but rather kip2 values. It seems that the binding sites available on the surface of the composites cannot effectively differentiate between L-Tyr and D-Tyr. Enantiomeric selective adsorption is realized as adsorbate molecules diffuse to the interior of the composite because chirality of the CS and CEL makes it possible for it to chirally discriminate against both enantiomers of Tyr, and the discrimination increases as Tyr molecules diffuse into pore of the particle in the interior of the composite. Selectivity is highest for 100% CS because the higher is the binding between Tyr molecules to the interior particles, the larger is the enantiomeric selectivity.

Figure 4.

Intraparticle diffusion plots for the sorption of D and L-Tyr from solutions with different concentrations and/or enantiomeric compositions by (A) 100CS; (B) CEL:CS and (C) 100CEL composite.

Table 1.

Intraparticle diffusion model parameters for sorption of Tyr enantiomers

| 100CS | CEL:CS | 100CEL | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ki1 | R2 | ki2 | R2 | ki1 | R2 | ki2 | R2 | ki1 | R2 | kis | R2 | |

| D Tyr Opt Active(UV) [5×10−4M] | - | - | 0.27±0.02 | 0.9086 | - | - | 0.28±0.01 | 0.9769 | - | - | 0.109±0.006 | 0.9616 |

| L Tyr Opt Active(UV) [5×10−4M] | - | - | 1.34±0.06 | 0.9722 | - | 0.67±0.02 | 0.9833 | - | - | 0.28±0.02 | 0.9495 | |

| D Tyr Racemic(HPLC) [5×10−4M] | - | - | 1.0±0.2 | 0.8455 | - | - | 0.17±0.04 | 0.8916 | - | - | −0.05±0.08 | 0.1438 |

| L Tyr Racemic(HPLC) [5×10−4M] | - | - | 1.5±0.1 | 0.9803 | - | - | 0.81±0.05 | 0.9933 | - | - | 0.07±0.07 | 0.3482 |

| D Tyr(HPLC) [3.33×10−4M] | 0.02±0.09 | 0.0092 | 0.29±0.06 | 0.7739 | 0.27±0.06 | 0.8518 | 0.23±0.03 | 0.8697 | 0.08±0.08 | 0.1986 | 0.03±0.02 | 0.1974 |

| L Tyr(HPLC) [6.67×10−4M] | 0.2±0.1 | 0.297 | 1.5±0.1 | 0.9539 | 0.52±0.09 | 0.8845 | 1.02±0.07 | 0.9658 | 0.14±0.08 | 0.4311 | 0.30±0.04 | 0.8584 |

| DL Tyr Racemic(UV) [1×10−3M] | 0.22±0.02 | 0.9678 | 1.34±0.05 | 0.9841 | 0.25±0.06 | 0.8411 | 0.43±0.02 | 0.9641 | 0.12±0.05 | 0.6042 | 0.036±0.008 | 0.6297 |

| Pure L Tyr(UV) [1×10−3M] | 0.26±0.04 | 0.9314 | 2.71±0.07 | 0.9935 | 0.22±0.02 | 0.9547 | 1.71±0.04 | 0.9931 | 0.13±0.02 | 0.9580 | 0.19±0.01 | 0.9382 |

Table 2.

Intraparticle diffusion model parameters for the sorption of His enantiomers

| 100CS | CEL:CS | 100CEL | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| ki1 | R2 | ki2 | R2 | ki1 | R2 | ki2 | R2 | ki1 | R2 | ki2 | R2 | |

|

| ||||||||||||

| D His Opt Active(UV) [5×10−4M] | - | - | 0.08 | 0.7954 | - | - | 0.11 | 0.4983 | - | - | 0.06 | 0.6409 |

| L His Opt Active(UV) [5×10−4M] | - | - | 1.08 | 0.9057 | - | - | 0.94 | 0.9888 | - | - | 0.75 | 0.7015 |

| D His Racemic(HPLC) [5×10−4M] | - | - | 0.22 | 0.9010 | - | - | 0.11 | 0.8180 | - | - | 0.16 | 0.9257 |

| L His Racemic(HPLC) [5×10−4M] | - | - | 1.53 | 0.9753 | - | - | 1.41 | 0.9943 | - | - | 1.25 | 0.9949 |

Table 3.

Intraparticle diffusion model parameters for the sorption of Trp enantiomers

| 100CS | CEL:CS | 100CEL | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| ki1 | R2 | ki2 | R2 | ki1 | R2 | ki2 | R2 | ki1 | R2 | ki2 | R2 | |

|

| ||||||||||||

| D Trp Opt Active(UV) [5×10−4M] | - | - | 0.21 | 0.9038 | - | - | 0.18 | 0.9525 | - | - | 0.04 | 0.8653 |

| L Trp Opt Active(UV) [5×10−4M] | - | - | 0.71 | 0.9712 | - | - | 0.55 | 0.9832 | - | - | 0.25 | 0.9905 |

| D Trp Racemic(HPLC) [5×10−4M] | - | - | 0.21 | 0.3962 | - | - | 0.10 | 0.5193 | - | - | 0.06 | 0.0782 |

| L Trp Racemic(HPLC) [5×10−4M] | - | - | 1.44 | 0.9224 | - | - | 0.84 | 0.9924 | - | - | 0.36 | 0.8891 |

The 100%CS has the highest and 100% CEL has the lowest enantiomer selectivity. The fact that the 50:50 CS:CEL composite exhibits not only relatively high selectivity but also is more similar to 100%CS than to 100%CEL. This is very encouraging because as described in our previous work, CS has relatively poor rheological and mechanical properties and is known to undergo swelling in water.37 Adding CEL to CS not only improves its rheological and mechanical properties but also reduces its swelling.24,25 In fact, we showed that adding 50% of CEL to CS increases its tensile strength by 2X and reduces its swelling by 35%.24,25 Taken together, the results indicate that a 50:50 CS:CEL composite has good enantiomer selectivity and adequate rheological properties required for daily practical use.

The sorption selectivity for the racemic mixtures of different amino acids can be calculated using the following equation:30

| (3) |

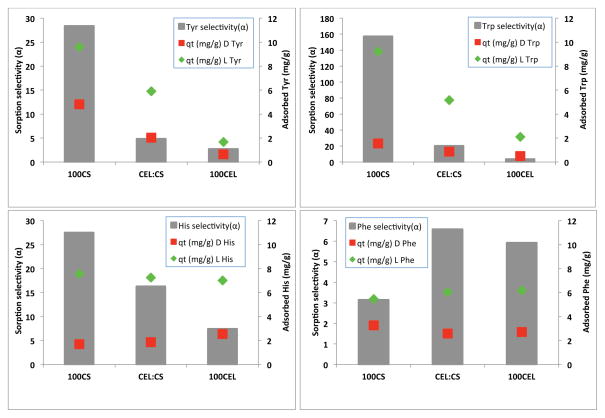

where cLi and cLf denote the initial and final L concentration of the L-enantiomer, and cDi and cDf is the initial and final concentration of D-enantiomer, respectively. The sorption selectivity was calculated for the HPLC experiments with 1.0×10−3M racemic solutions after 96 hrs. The 96 hr time period was selected as this was generally the amount of time it took for the HPLC band of the L-enantiomer to disappear for the 100CS composite material. Results obtained for different amino acids together with the amount of each enantiomer adsorbed at this time are shown in Figure 5. The sorption selectivity is indicated by the grey bars, adsorbed L-enantiomer and D-enantiomer are shown as the green diamond and the red squares, respectively. It is clear that except Phe, for all other three amino acids (Tyr and Trp and His), the enantioselectivity of the different composites was found to follow the order 100CS > CEL:CS > 100CEL. Since the amount of amino acid adsorption is highest for 100CS and lowest for 100CEL with CEL:CS is in the middle, the order of the enantioselectivity seems to be closely related to the adsorbed amount of amino acid. Also, the amount of L enantiomer adsorbed is progressively larger than that of the D enantiomer, and again the largest difference was found to be largest for 100CS and smallest for 100CEL. As explained in previous section, this was the reason for the 100CS composite to have the highest sorption selectivity. Interestingly, different from other three amino acids, Phe exhibits different selectivity for all three composites. The adsorbed amount of both the D-Phe and L-Phe was generally the same for 100%CS, 50:50 CS:CEL and 100%CEL, Furthermore, the amount of L Phe adsorbed by the 100CS composite was unexpectedly lower compared to the other 3 amino acids. This might have contributed to the relatively low selectivity observed for Phe with this composite material. Also, it is possible that enantioselectivity is also dependent on the initial amino acid concentration. Further study is needed to determine this possibility.

Figure 5.

Comparison of the selectivity of the different composite materials with the 4 amino acids studied. Initial concentration of each racemic amino acid was 1.0×10−3M.

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, the polysaccharide composite materials developed here have shown promising potential application in chiral separations. Preliminary results with 4 different amino acids show that racemic mixtures can potentially be resolved by selective adsorption of the L enantiomer in a period from about 96 to 120 hrs for the 100%CS composite material. The [CEL+CS] composite material, which has relatively superior rheological and mechanical properties, also exhibits good enantioselectivity. The analysis of the enantiomeric adsorption using the intraparticle diffusion model showed that very little to no adsorption was occurring in the first 16 hrs. This is then followed by a period of steady adsorption in which the intraparticle diffusion rate constant of the L enantiomer is higher than that of the D enantiomer. This difference in diffusion rate constants possibly plays a significant role in the enantiomeric resolution that was observed with these polysaccharide composite materials.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award number R15GM099033.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Plots of adsorption of Tyr solutions with different concentrations and/or enantiomeric compositions by 100CS, CEL:CS and 100CEL determined by both UV-vis and chiral HPLC. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Chem Eng News. 1990;68(19):38–44. [Google Scholar]; 1992;70(28):46–79. [Google Scholar]; 2001;79:45–56. 79–97. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Armstrong DW, Han SH. Enantiomeric separations in chromatography. CRC Crit Rev Anal Chem. 1988;19:175. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hinze WH. Applications of cyclodextrins in chromatographic separations and purification methods. Sep Pur Methods. 1981;10:159. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Armstrong DW. Optical isomer separation by liquid chromatography. Anal Chem. 1987;59:84A. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hinze WL, Armstrong DW. Organized surfactant assemblies in separation science. ACS Symposium Ser. 1987;342:2–82. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tran CD, Kang J. Chiral Separation of Amino Acids by Capillary Electrophoresis with Octyl-β-thioglucopyranoside as Chiral Selector. J Chromatogr, A. 2002;978:221–230. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(02)01386-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tran CD, Kang J. Chiral Separation of Amino Acids by Capillary Electrophoresis with 3-[(3-Cholamidopropyl)-dimethylammonio]-1-propane sulfonate (CHAPS) as Chiral Selector. Chromatographia. 2003;57:81–86. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhou Z, Xiao Y, Hatton TA, Chung TS. Effects of spacer arm length and benzoation on enantioseparation of performance of beta-cyclodextrin fuctionalized cellulose membrances. J Membrane Sci. 2009;339:21–27. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xiao YC, Chung TS. Functionalization of cellulose dialysis membranes for chiral separation using beta-cyclodextrin immobilization. J Membrane Sci. 2007;290:78– 85. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhou Z, Cheng JH, Chung TS, Hatton TA. The exploration of the reversed enantioselectivity of a chitosan functionalized cellulose acetate membranes in an electric field driven process. J Membrane Sci. 2012;389:372–379. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Finkenstadt VL, Millane RP. Crystal Structure of Valonia Cellulose 1β. Macromolecules. 1998;31:7776–7783. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Augustine AV, Hudson SM, Cuculo JA. In: Cellulose Sources and Exploitation. Kennedy JF, Philipps GO, Williams PA, editors. New York: E. Horwood; 1990. p. 59. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kadokawa J, Murakami M, Kaneko Y. Composites Science and Technology. 2008;68:493–498. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dawsey TR. Cellulosic Polymers, Blends and Composites. Carl Hanser Verlag; New York: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dai T, Tegos GP, Burkatovskaya M, Castano AP, Hamblin MR. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 2009;53:393–400. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00760-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bordenave N, Grelier S, Coma V. Hydrophobization and antimicrobial activity of chitosan and paper-based packaging material. Biomacromolecules. 2010;11:88–96. doi: 10.1021/bm9009528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rabea EI, Badawy MET, Stevens CV, Smagghe G, Steurbaut W. Chitosan as antimicrobial agent: Applications and mode of action. Biomacromolecules. 2003;4:1457–1465. doi: 10.1021/bm034130m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burkatovskaya M, Tegos GP, Swietlik E, Demidova TN, Castano AP, Hamblin MR. Use of chitosan bandage to prevent fatal infections developing from highly contaminated wounds in mice. Biomaterials. 2006;27:4157–4164. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.03.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kiyozumi T, Kanatani Y, Ishihara M, Saitoh D, Shimizu J, Yura H. Medium (DMEM/F12)-containing chitosan hydrogel as adhesive and dressing in autologous skin grafts and accelerator in the healing process. J Biomed Mat Res B: Appl Biomat. 2006;79B:129–136. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.30522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jain D, Banerjee R. Comparison of ciprofloxacin hydrochloride-loaded protein, lipid, and chitosan nanoparticles for drug delivery. J Biomed Mat Res B Appl Biomat. 2008;86:105–112. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.30994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tirgar A, Golbabaei F, Hamedi J, Nourijelyani K, Shahtaheri S, Moosavi S. Int J Environ Sci Tech. 2006;3:305–313. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nishiki M, Tojima T, Nishi N, Sakairi N. β-Cyclodextrin-linked chitosan beads: preparation and application to removal of bisphenol A from water. Carbohydrate Let. 2000;4:61–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Duri S, Tran CD. Supramolecular composite materials from cellulose, chitosan, and cyclodextrin: Facile preparation and their selective inclusion complex formation with endocrine disruptor. Langmuir. 2013;29:5037–49. doi: 10.1021/la3050016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tran CD, Duri S, Harkins AL. Recyclable synthesis, characterization and antimicrobial activity of cellulose-based polysacchrdie composite materials- J Biomed Mat Res A. 2013:1–10. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.34520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tran CD, Duri S, Delneri A, Franko M. Chitosan-cellulose composite materials: Preparation, characterization and application for removal of microcystin. J Hazard Mat. 2013;252–253:355–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2013.02.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weber JW, Morris JC. Kinetics of adsorption of carbon from solution. J Sanit Eng Div Am Soc Civ Eng. 1963;89:31–39. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hameed BH, Chin LH, Rengaraj S. Adsorption of 4-chlorophenol onto activated carbon prepared from rattan sawdust. Desalination. 2008;225:185–198. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Elsherbiny AB, Salem MA, Ismail AA. Influence of alkyl chain length of cyanine dyes on adsorption by Na+-montmorillonite from aqueous solutions. Chem Eng J. 2012;200:283–290. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gu W, Sun C, Liu Q, Cui H. Adsorption of avermectins on activated carbon: Equilibrium, kinetics, and UV-shielding. Trans Nonferrous Met Soc China. 2009;19:845–850. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang HD, Chu LY, Song H, Yan JP, Xie R, Yang M. Preparation and enantiomer separation characteristics of chitosan/β-cyclodextrin composite membranes. J Membrane Sci. 2007;297:262–270.0. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.