Abstract

Background

We aimed to determine the feasibility of monitoring viral delivery and initial distribution to solid tumors using iodinated contrast agent and micro-computed tomography (CT).

Methods

Human BxPC-3 pancreatic tumor xenografts were established in nude mice. An oncolytic measles virus with an additional transcriptional unit encoding the sodium iodide symporter (NIS), as a reporter for viral infection, was mixed with a 1:10 dilution of Omnipaque 300 (GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI, USA) contrast agent and injected directly into tumors. Mice were imaged with micro-CT immediately before and after injection to determine the location of contrast agent/virus mixture. Mice were imaged again on day 3 after injection with micro-single-photon emission CT/CT to determine the location of NIS-mediated 99mTcO4 transport.

Results

A 1:10 dilution of Omnipaque had no effect on viral infectivity or cell viability in vitro and was more than adequate for CT imaging of the intratumoral injectate distribution. The volume of tumor coverage with initial CT contrast agent and the 3-day postinfection measurement of virally infected tumor volume were significantly correlated. Additionally, regions of the tumor that did not receive contrast agent from the initial injection were largely devoid of viral infection at early time points.

Conclusions

Contrast-enhanced viral delivery enables a rapid and accurate prediction of the initial viral distribution within a solid tumor. This technique should enable real-time monitoring of viral propagation from initially infected tumor regions to adjacent tumor regions.

Keywords: iodinated contrast agent, Omnipaque, oncolytic measles, pancreatic cancer, sodium-iodide symporter, SPECT/CT

Introduction

Viruses that can selectively infect or selectively replicate in tumor cells (oncolytic viruses) are attractive candidates for the targeted treatment of solid tumors [1]. In our laboratory, we use a tumor-selective, highly fusogenic measles vaccine derivative engineered to express the sodium iodide symporter (NIS). NIS-mediated uptake of 99mTcO4, 123I, 125I, 124I or [18F]-tetrafluoroborate permits single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) or positron emission tomography imaging of zones of viral infection [2–6]. Using NIS-mediated reporter imaging techniques, we can visualize viral distribution after the initial round of infection and amplification via cell-to-cell spread: a process that takes approximately 72 h.

The inability to deliver virus homogeneously throughout solid tumors is a universal obstacle encountered in oncolytic virotherapy [7–12]. Direct oncolytic viral therapy requires replicative viral spread from the initial zones of infection to adjacent regions of the tumor. Several barriers (i.e. both temporal and spatial) to the spread of viruses exist in solid tumors. These include innate and adaptive immunity and zones of hypoxia, necrosis, fibrosis and inflammation [13–19]. Many efforts are under way to engineer or adapt new oncolytic platforms that are better suited for spread within the architecture of a solid tumor [20–24].

One way of monitoring oncolytic virus propagation in vivo is the bilateral tumor model, in which one flank tumor is injected (source tumor) and the opposite flank tumor serves as a sink for virus released from the source tumor or from infected mouse tissue [25–28]. The bilateral model is attractive because it mimics the clinical situation, in which not all tumor sites are known, and directly tests the most desirable attribute of an oncolytic virus: the ability to amplify and spread systemically. However, for human-specific viruses, particularly viruses that spread by infected host cell carriers, the bilateral tumor mouse model is not particularly useful. Therefore, we aimed to design a tumor model and imaging strategy to monitor viral propagation within a tumor.

We investigated a model in which dual-flank tumors are used for the more efficient use of animal resources, although each tumor is independent. We hypothesized that, if one pole of each tumor was injected and the initial distribution of the viral injectate was documented by contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT), then non-invasive imaging could be used to monitor the progression of infection to regions of the tumor not covered by the initial injection. The hope is that this technique could be used to test new viral vector platforms aimed at enhancing tumor persistence or increasing intratumoral replication kinetics, as well as to test new mathematical models of virus propagation in three dimensions [29].

Materials and methods

Recombinant measles virus

A recombinant measles virus (MV) that contains an additional gene encoding human NIS (MV-NIS) was described previously [2]. MV-NIS was used for in vivo imaging studies to monitor and quantitate intratumoral viral infection. The MV-NIS preparation used in all experiments was produced by the Mayo Clinic Viral Vector Production Laboratory [30,31] and contains a 3.5 × 107 Vero cell tissue culture infective dose (TCID50)/ml.

Animal maintenance

Experiments were approved by and performed in accordance with Mayo Clinic Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines. Five- to 7-week-old female nude mice were used in all experiments (Harlan Sprague–Dawley, Madison, WI, USA). Mice were housed in a pathogen-free barrier facility with access to food and water ad libitum. Mice were maintained on a PicoLab 5053 mouse diet (LabDiet, Richmond, IN, USA), which contains 0.97 p.p.m. total iodine.

Tumor xenografts

BxPC-3 human pancreatic cancer cells were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VI, USA) and maintained in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1× penicillin/streptomycin cocktail (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). To establish tumor xenografts, mice were inoculated subcutaneously in the flank with 3 × 106 BxPC-3 cells in 100 µl of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Mice were euthanized by CO2 gas inhalation, as recommended by the American Veterinary Medicine Association, at the end of the experiments or immediately if they met euthanization criteria (loss of approximately 15% body weight, inability to access food and water, tumor ulceration, or tumor burden exceeding 2 cm3).

Fluorescent microsphere experiment

Fluorescent microspheres similar in size to the MV particle (0.5 µm) were used to allow visualization of the initial intratumoral particle distribution immediately after injection. Fluoresbrite Polychromatic Red 0.5-µm microspheres (Polysciences, Inc, Warrington, PN, USA) were diluted to a concentration of 109/ml in PBS. Controlled intratumoral injections were performed with a foot pedal-initiated microsyringe pump and controller (Micro4) from World Precision Instruments (Sarasota, FL, USA). The microsphere suspension (100 µl) was injected into five mouse flank tumors at a single central location. Five minutes post injection, the mice were euthanized and the tumor was harvested. Frozen tumor sections were fixed in methanol and air dried, and a drop of mounting media containing 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) was added. Whole slides were scanned on a HistoRx multiplex fluorescent imager (Branford, CT, USA) using HistoRx Aquos software.

Intratumoral injection of omnipaque and virus

Dual-flank BxPC-3 tumors were established in a group of six mice (12 tumors). Bilateral intratumoral injections were performed under isoflurane anesthesia using a 27-gauge standard end-hole needle; 100 µl of viral injectate was used containing 10% (v/v) Omnipaque (iohexol) 300 mg I/ml contrast agent (GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI, USA) and 3.5 × 106 TCID50 MV-NIS per tumor, at an injection rate of 10 µl/s. The tip of the needle was placed one-quarter of the way into the tumor from either the superior or inferior pole. Before the study with virus, one mouse was used for an initial investigation of instrument parameters for contrast CT. The mouse was injected during CT acquisition with a prepositioned needle and imaged serially for 12 min. The remaining mice were imaged with micro-CT (described below) at 1, 2, 5 and 10 min after the Omnipaque/virus injection. Three days after infection, mice were imaged with 99mTcO4 micro-SPECT/CT and immediately sacrificed for immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining of intratumoral MV distribution. Previous studies have determined that day 3 post infection is the time of peak NIS-mediated radiotracer uptake from the initial round of viral spread in the this model [4].

Small animal imaging system

A high-resolution micro-SPECT/CT system (X-SPECT; Gamma Medica Ideas, Inc, Northridge, CA, USA) was used for micro-CT and fusion micro-SPECT/CT imaging. A detailed description of the instrument has been provided previously [32]. This system offers small animal functional and anatomical imaging with a micro-CT resolution of approximately 155 µm and a micro-SPECT resolution of 3–4 mm (using a low-energy, high-resolution, parallel-hole collimator with a 12.5-cm field of view) or resolution approaching 1 mm (using a 1-mm pinhole collimator). Mice were injected intraperitoneally with 1 mCi (37 MBq) of 99mTcO4 1 h before imaging, on the basis of previous data [32]. During imaging, animals were induced briefly with 3–4% gaseous isoflurane in O2 and maintained at 1–2% isoflurane in O2 throughout the procedure. The anesthesia was tightly controlled with a surgical vaporizer (Summit Medical, Bend, OR, USA) and delivered through mouse-specific nose cones. With a combined intratumoral viral dose to each mouse of 7 × 106 TCID50 (in 200 µL of injectate), approximately 30% of mice failed to recover from anesthesia following imaging. Imaging data was only included in the analysis if the animal recovered in a normal, timely manner. For pinhole micro-SPECT imaging, we used a 5-cm radius of rotation and obtained 64 projections at 15 s per projection with a resolution of approximately 2 mm. Micro-CT image acquisition (155-µm slice thickness, 256 images) was performed in 1 min at 0.25 mA and 80 kV peak.

Image analysis and quantification

Whole-body radiotracer activity (injected dose) in each mouse was determined by measuring activity in the syringe in a National Institute of Standards and Technology (Gaithersburg, MD, USA)-calibrated dose calibrator before and after injection and correcting for decay between the time of injection and time of analysis. Subcutaneous tumor activity was determined by volume-of-interest micro-SPECT/CT image analysis using PMOD Biomedical Image Quantification and Kinetic Modeling Software (PMOD Technologies, Zurich, Switzerland).

Tumor harvest and IHC for measles N protein

Mice were euthanized immediately after micro-SPECT/CT imaging. Tumors were excised and weighed, and 99mTcO4 activity was counted in a dose calibrator. Tumors were placed in a Tissue-Tek Cryomold (Sakura, Torrance, CA, USA) and embedded in optimal cutting temperature compound. tissue freezing medium in the same orientation as they appeared on rotated coronal micro-SPECT/CT images that were reconstructed using PMOD software. Ten equally spaced frozen sections were obtained from each tumor. Slides were incubated with a biotinylated mouse anti-measles N protein monoclonal antibody (MAB8906B; Chemicon, Billerica, MA, USA) and developed with Vectastain Elite ABC kit and a diaminobenzidine kit (both from Vector Laboratories). Slides were counterstained in hematoxylin and scanned with a Nanozoomer Digital Pathology System (Bacus Laboratories, Center Valley, PA, USA) using a × 20 objective.

Statistical analysis

Linear regression and Spearman correlation analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism, version 4 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA).

Results

Intratumoral barriers to viral dispersion and spread

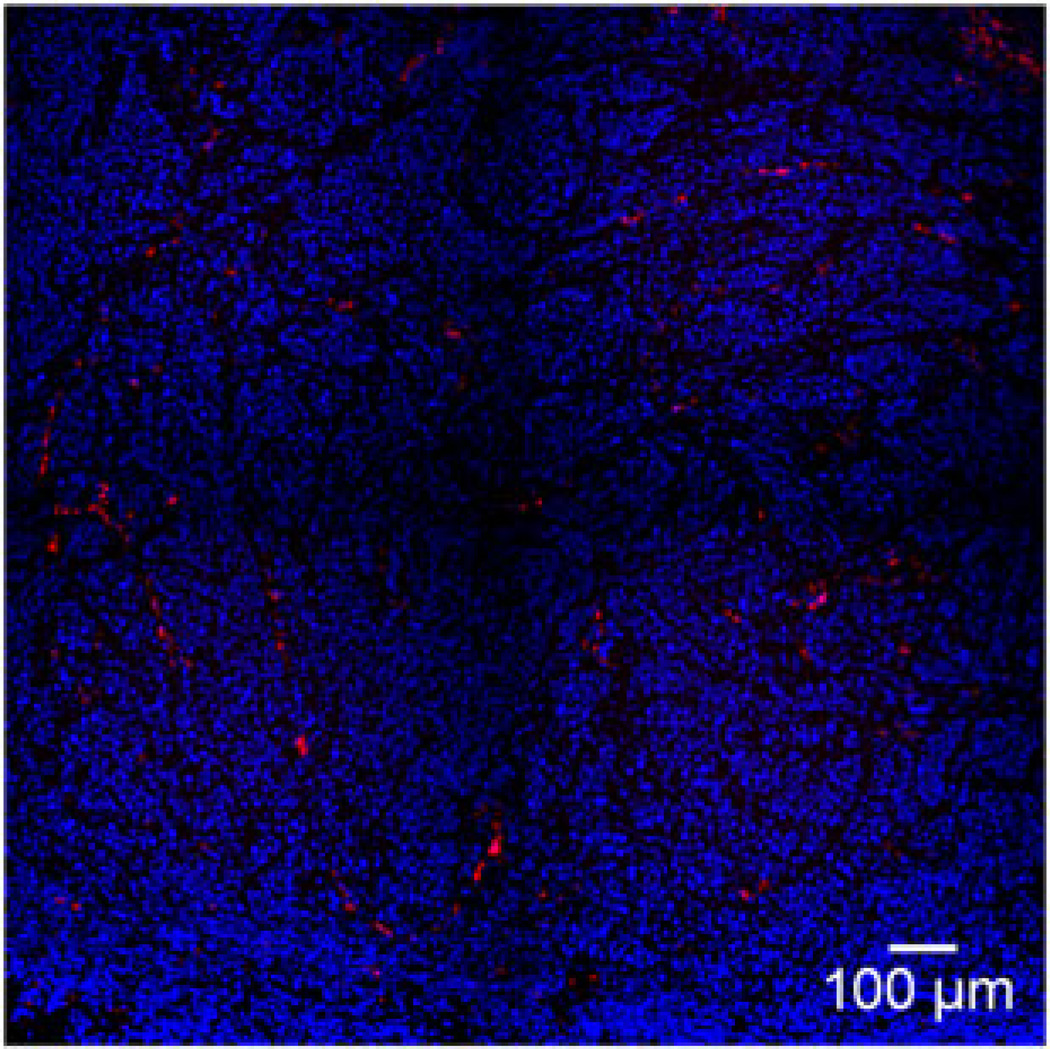

The BxPC-3 pancreatic cancer flank tumors established in the nude mice were multinodular and encapsulated (Figure 1A). By histologic analysis, they were shown to have extensive fibroblast infiltration and deposition of collagen fibrils (Figures 1B and 1C). To better understand the properties governing initial viral delivery, we then directly injected these BxPC-3 tumor xenografts with Fluoresbrite microspheres. After tumors were harvested, histology and fluorescence microscopy showed the injectate pattern to be approximately spherical, with a spoke-like distribution along the human tumor cell–mouse fibroblast boundary (Figure 2; see also Supporting information, Figures 1 and 2). The capsule of the xenograft tumor did not appear to deflect or redirect the distribution of the microspheres. Rather, the spherical deposition of virus simply appeared to continue outside the boundary of the tumor as the capsule burst from the injection pressure. The forces created by the injection, even with moderate and well-controlled injection parameters, apparently were sufficient to overcome capsule containment, particularly when large injectate volumes were used relative to tumor size or, more accurately, when the injectate volume was large relative to the shortest diameter from the injection mid point to the tumor capsule (see Supporting information, Figure S1).

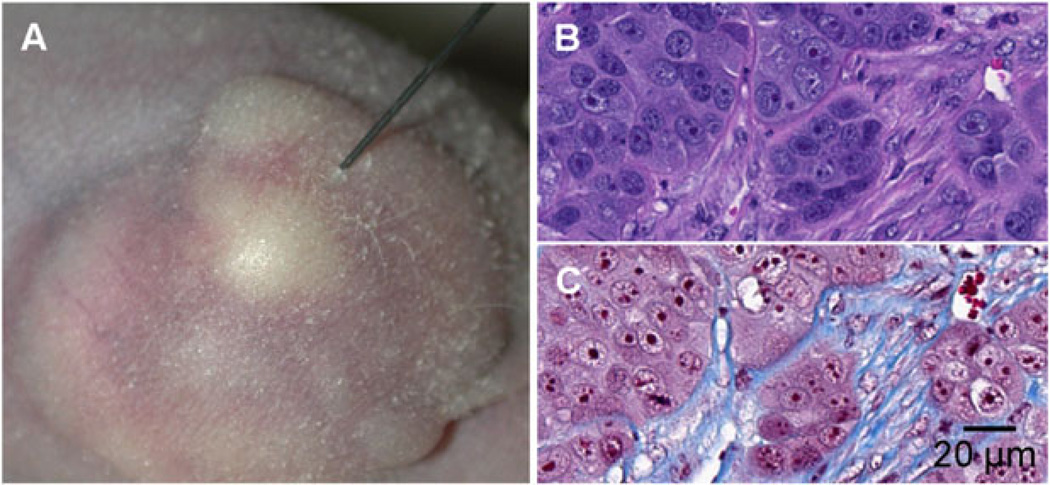

Figure 1.

Tumor characteristics. (A) Representative image of a BxPC-3 subcutaneous tumor being injected with MV-NIS. (B, C) Tumor sections of BxPC-3 xenograft stained with hematoxylin and eosin (B) and Masson’s trichrome (C) showing densely packed tumor cell clusters surrounded by networks of fibroblasts and collagen fibrils (blue staining in C).

Figure 2.

Intratumoral fluorescent microspheres. A BxPC-3 xenograft with a central intratumoral injection of fluorescent microspheres (500 nm) was fixed and stained with 4′, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole. Note the alignment of fluorescent microspheres along the tumor cell–stroma boundaries.

Evaluation of Omnipaque/MV-NIS solution for contrast-enhanced CT imaging

The experiments with fluorescent microspheres pointed to the sometimes unpredictable nature of initial virus distribution; and it was apparent that, if we wanted to observe spread of virus through a tumor, we needed to know the location of the virus at time zero. We hypothesized mixing of iodinated contrast agent and MV-NIS combined with CT imaging would provide an accurate ‘snapshot’ of the initial distribution. For initial validation of the approach, we performed micro-CT imaging of a dilution series of Omnipaque 300 using the same settings typically used for reporter gene micro-SPECT/CT imaging (see Supporting information, Figure S3). These results showed that a 10% solution of contrast agent was more than adequate for detection on CT. Testing the effects of 10% Omnipaque in vitro confirmed that Omnipaque had no inhibitory effects on viral infection (see Supporting information, Figure S4) and had no observable effect on the cultured cells.

Correlation between CT contrast volume and infection volume

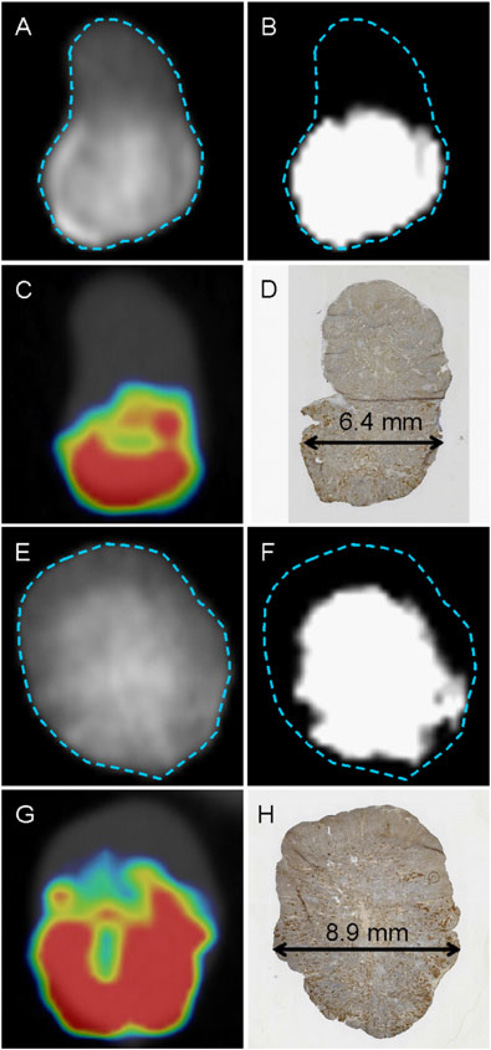

Flank tumors were injected with a mixture of 10% Omnipaque and 3.5 × 106 MV-NIS (Figure 3). To determine whether there was a significant correlation between CT contrast volume and viral infection volume, we first established a method to isolate regions of the tumor that contained the contrast agent. We empirically chose a background cut-off value of 1300 PMOD CT units, which filtered out all background CT attenuation in tumors before injection of contrast. The amount of tumor tissue with a contrast enhancement value above 1300 CT units was measured with volume-of-interest analysis, taking care to exclude extratumoral regions of contrast agent. The measured viral infection distribution volumes exhibit an approximately spherical shape about the injection site and were, on average, 1.6 times larger than the injection volume, with larger tumors apparently able to accommodate more fluid (up to three times the injection volume) (Table 1). Note that, in the two examples shown (Figure 3) and in the other eight tumors examined, there was a general lack of SPECT signal in geometrical regions of the tumor that were below a threshold level of contrast enhancement.

Figure 3.

Injection of Omnipaque Plus MV-NIS. Representative sections from two tumors after both were injected at a single site in the inferior pole. Images (A) to (D) (tumor 1) and (E) to (H) (tumor 2) show the spatial relationship between tumor contrast-enhanced CT imaging and IHC for measles virus. (A, E) CT 1 min post injection (scale, 800–2000 counts) showing tumor boundary. (B, F) Same view as in (A) but with the scale adjusted to show regions with contrast agent above threshold (1300–1400 CT counts). (C, G) Micro-SPECT/CT of NIS reporter activity on day 3 post injection of Omnipaque/MV-NIS. (D, H) IHC for measles N protein (brown) immediately after micro-SPECT/CT imaging. The double-arrowed line shows the diameter of the tumor at the site of injection. Tumor 1 shows contrast agent and infection distributed to approximately 50% of the tumor. Tumor 2 shows contrast agent and infection lacking in the superior region of the tumor. Care was taken when harvesting the tumors to enable alignment with coronal sections after rotation of the imaging data set.

Table 1.

Tumor characteristics

| Tumor | Mass (g) | Threshold voxels |

Mean threshold voxel intensity |

Contrast volume (cm3) | Volume of infection by IHC (cm3) |

% ID/g |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 56L | 0.593 | 1997 | 1435 | 0.078 | 0.199 | 5.7 |

| 518L | 0.428 | 3589 | 1495 | 0.141 | 0.301 | 14.4 |

| 364L | 0.41 | 1559 | 1447 | 0.061 | 0.207 | 9.3 |

| 102L | 0.295 | 1833 | 1504 | 0.072 | 0.228 | 15.1 |

| 518R | 0.293 | 1340 | 1457 | 0.053 | 0.212 | 10.5 |

| 102R | 0.271 | 363 | 1431 | 0.014 | 0.205 | 12.5 |

| 821L | 0.256 | 1074 | 1620 | 0.042 | 0.136 | 12.4 |

| 364R | 0.203 | 521 | 1480 | 0.02 | 0.067 | 10.6 |

| 56R | 0.139 | 510 | 1447 | 0.02 | 0.062 | 11.5 |

| 821R | 0.127 | 752 | 1429 | 0.03 | 0.045 | 15.9 |

| Mean (SE) | 0.302 (0.05) | 1354 (308) | 1475 (18) | 0.053 (0.01) | 0.166 (0.03) | 11.8 (1) |

ID/g, percentage of injected dose per gram of tumor.

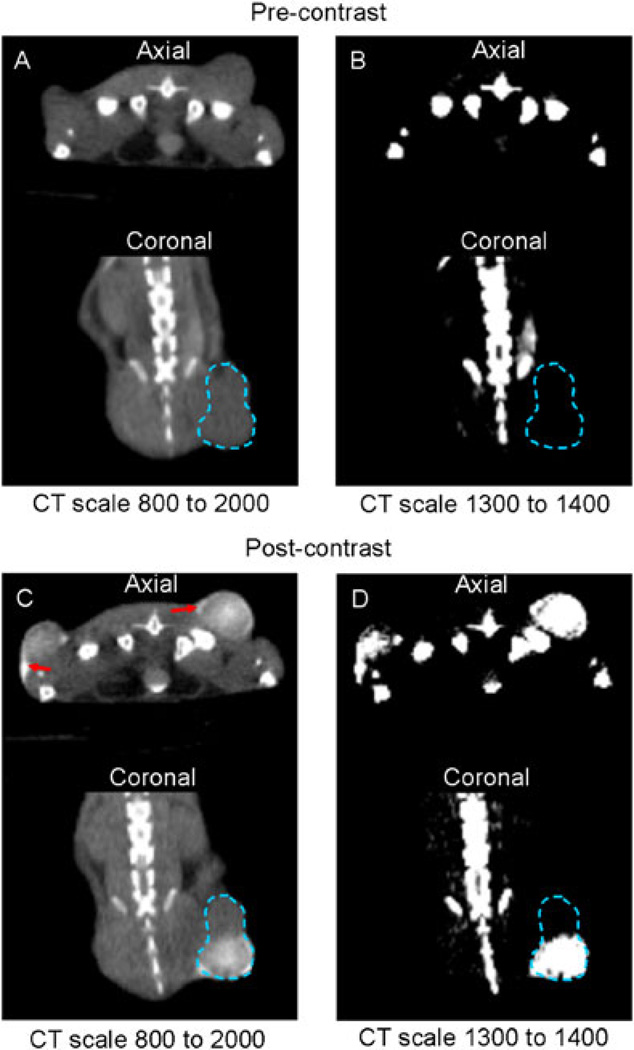

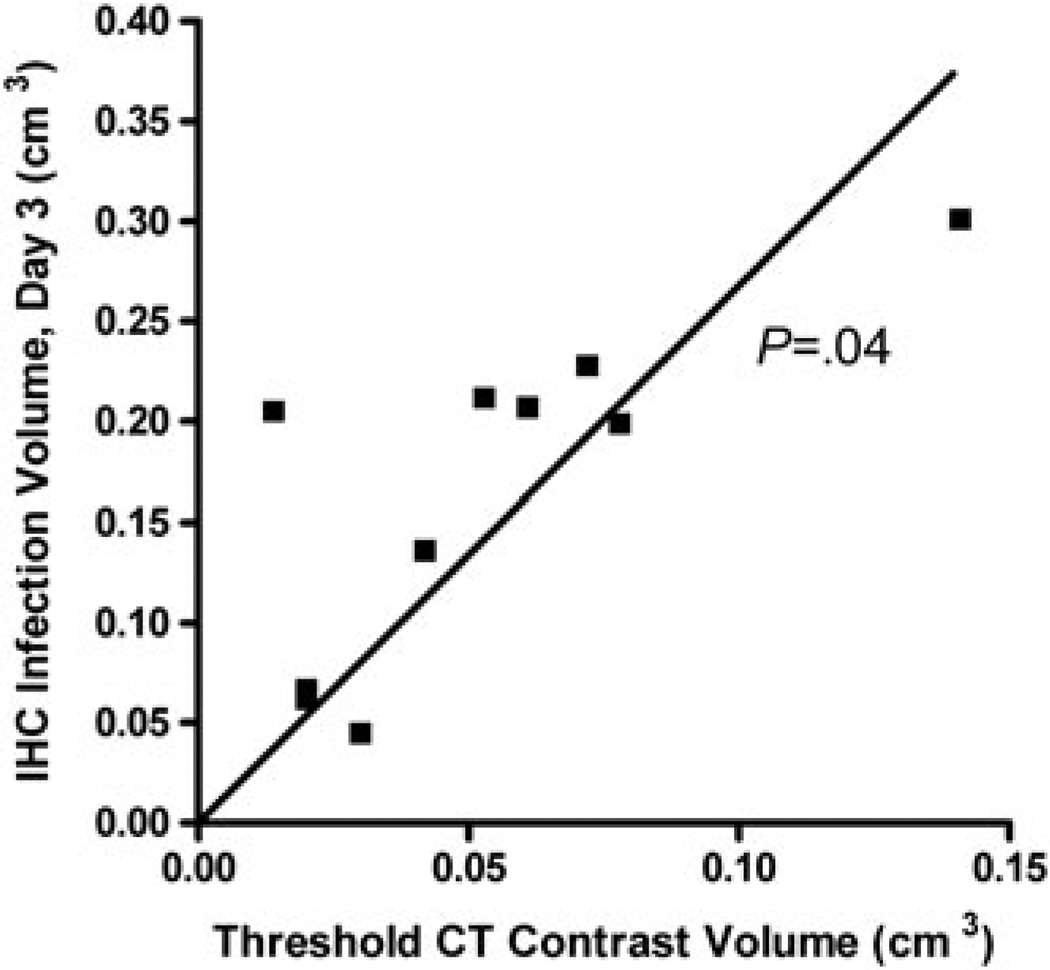

In addition to the visual–spatial relationship between CT contrast and SPECT, we anticipated a correlation that reflected the retention of injectate in the tumor versus inadvertent distribution of much of the injectate (and thus virus) to extratumoral mouse tissue, which is not permissive to measles. Figure 4 shows a mouse with dual-flank tumors imaged before and after Omnipaque/MV-NIS injection and the PMOD grayscale settings used for volume-of-interest analysis. We observed a significant positive correlation between the intratumoral contrast volume on imaging at 1 minute post injection and the viral infection volume (determined by IHC) on day 3 (Figure 5). We hypothesize that the slope of the regression line (2. 7 IHC cm3/contrast cm3) is the result of a combination of tumor growth between day 0 and day 3 and a slight underestimation of injectate distribution using the threshold of 1300 CT units.

Figure 4.

Representative CT Images. Axial and coronal CT images before and after injection of MV-NIS and Omnipaque. (A, B) Precontrast tumor with a standard CT scale (A) and thresholded to exclude background soft tissue (voxel counts < 1300 CT counts) (B). (C, D) The same tumor imaged 1 min after injection is shown with the same CT scales as in (A) and (B). Red arrows show regions of extratumoral contrast agent pooling.

Figure 5.

Correlation between threshold contrast volume and infected tumor volume. Correlation analysis between threshold (> 1300 PMOD CT units) intratumoral contrast volume immediately after injection and infected tumor volume on day 3 post injection, as determined by IHC. The slope of the linear regression line was 2.7 IHC volume/CT contrast volume. Spearman correlation analysis yielded (p = 0.04).

In general, there was more extratumoral deposition of the contrast agent in small tumors and better retention in larger tumors (Table 1). Interestingly, in the threshold regions of contrast localization, all tumors had approximately the same mean CT voxel intensity (i.e. concentration of contrast agent). This probably reflects the relatively uniform nature of the tumors, with most of the volume occupied by tumor cells. As expected, there was no correlation between intratumoral Omnipaque (contrast enhancement) and the percentage of injected dose per gram of intratumoral NIS-mediated 99mTcO4 uptake. This relationship was dominated by the mass of tumor (i.e. bigger tumors had a proportionally lower percentage injected dose per gram because all tumors were injected with same number of infectious virions). The mean percentage injected dose per gram was slightly higher than we have found in previous studies [4,10,33] using the same model, confirming the in vitro conclusion that mixing the Omnipaque and virus has no inhibitory effects on infection.

Discussion

We have demonstrated that (i) the intravenous contrast agent Omnipaque 300 can be mixed with MV-NIS before intratumoral injection without affecting viral infectivity and (ii) immediate post-injection CT imaging enables a reasonable prediction of zones of the tumor that were not ‘covered’ by virus in the initial distribution. Thus, despite the large difference in hydrodynamic volume between the small contrast agent molecules and the large enveloped MV, both appear to follow a general bulk fluid replacement model of initial distribution.

There were marked differences in sensitivity and resolution between CT and SPECT. The resolution of our CT system is approximately 0.155 cm, whereas the resolution of SPECT with the settings used is approximately 2 mm. The threshold for contrast enhancement that we used corresponds to a concentration of iodine in the millimolar range (approximately 1018 I/ml). For SPECT reporter imaging, a few hundred virions (each resulting in the fusion of 100 or more neighboring cells) can result in a signal above background. By comparison, a single syncytium (ultimately from a single deposited virion) is readily discernible by ex vivo IHC with an antibody against MV. Adding to the complexity of comparison, this xenograft model approximately doubles in volume between day 0 and day 3. Thus, with these caveats in mind, we are satisfied that we observed a reasonable relationship between regions of the tumor not covered by contrast at the initial injection and regions of the tumor devoid of viral infection at day 3.

The present study represents the first step in estimating the initial distribution of viral vectors in solid tumors and provides a methodological tool for evaluating different spatial and temporal injection schemes to optimize viral (and perhaps other large molecule) delivery to solid tumors.

In conclusion, intratumoral viral delivery can be monitored using image-guided injection techniques. Contrast-enhanced viral delivery enables a rapid and accurate view of the initial viral distribution within a solid tumor. This injection method should enable testing of new oncolytic viral platforms and mathematical models of intratumoral viral propagation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank our nuclear medicine technologist, Teresa Decklever (Mayo Clinic), for technical expertise and imaging assistance. This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute (grant K08 CA103859 and grant P50 CA102701 from the Mayo Clinic SPORE in Pancreatic Cancer) and the Arnold Palmer Foundation Career Development Award.

Footnotes

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Supporting information

The following supplementary material can be found in the online article.

Figure S1. Visualization of fluorescent microspheres. A BxPC-3 xenograft tumor with a single central intratumoral injection of fluorescent microspheres (0.5 µm) was fixed and stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole.

Figure S2. Visualization of fluorescent microspheres. BxPC-3 xenograft injected intratumorally with 0.5 µm red fluorescent microspheres.

Figure S3. Micro-CT image of a dilution series of Omnipaque 300 in PBS.

Figure S4. Effect of 10% Omnipaque 300 on the infection of cultured cells with measles virus containing and an additional gene encoding human green fluorescent protein (MV-GFP).

References

- 1.Kelly E, Russell SJ. History of oncolytic viruses: genesis to genetic engineering. Mol Ther. 2007;15:651–659. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dingli D, Peng KW, Harvey ME, et al. Image-guided radiovirotherapy for multiple myeloma using a recombinant measles virus expressing the thyroidal sodium iodide symporter. Blood. 2004;103:1641–1646. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-07-2233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dingli D, Kemp BJ, O’Connor MK, et al. Combined I-124 positron emission tomography/computed tomography imaging of NIS gene expression in animal models of stably transfected and intravenously transfected tumour. Mol Imaging Biol. 2006;8:16–23. doi: 10.1007/s11307-005-0025-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carlson SK, Classic KL, Hadac EM, et al. Quantitative molecular imaging of viral therapy for pancreatic cancer using an engineered measles virus expressing the sodium-iodide symporter reporter gene. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;192:279–287. doi: 10.2214/AJR.08.1205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jauregui-Osoro M, Sunassee K, weeks AJ, et al. Synthesis and biological evaluation of [(18)F]tetrafluoroborate: a PET imaging agent for thyroid disease and reporter gene imaging of the sodium/iodide symporter. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2010;37:2108–2116. doi: 10.1007/s00259-010-1523-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Groot-Wassink T, Aboagye EO, Wang Y, et al. Quantitative imaging of Na/I symporter transgene expression using positron emission tomography in the living animal. Mol Ther. 2004;9:436–442. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2003.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Netti PA, Berk DA, Swartz MA, Grodzinsky AJ, Jain RK. Role of extracellular matrix assembly in interstitial transport in solid tumours. Cancer Res. 2000;60:2497–2503. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cairns R, Papandreou I, Denko N. Overcoming physiologic barriers to cancer treatment by molecularly targeting the tumour microenvironment. Mol Cancer Res. 2006;4:61–70. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-06-0002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheng J, Sauthoff H, Huang Y, et al. Human matrix metalloproteinase-8 gene delivery increases the oncolytic activity of a replicating adenovirus. Mol Ther. 2007;15:1982–1990. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Penheiter AR, Wegman TR, Classic KL, et al. Sodium iodide symporter (NIS)-mediated radiovirotherapy for pancreatic cancer. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;195:341–349. doi: 10.2214/AJR.09.3672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nagano S, Perentes JY, Jain RK, Boucher Y. Cancer cell death enhances the penetration and efficacy of oncolytic herpes simplex virus in tumours. Cancer Res. 2008;68:3795–3802. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hong CS, Fellows W, Niranjan A, et al. Ectopic matrix metalloproteinase-9 expression in human brain tumour cells enhances oncolytic HSV vector infection. Gene Ther. 2010;17:1200–1205. doi: 10.1038/gt.2010.66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harrison D, Sauthoff H, Heitner S, et al. Wild-type adenovirus decreases tumour xenograft growth, but despite viral persistence complete tumour responses are rarely achieved – deletion of the viral E1b-19-kD gene increases the viral oncolytic effect. Hum Gene Ther. 2001;12:1323–1332. doi: 10.1089/104303401750270977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heise CC, Williams A, Olesch J, Kirn DH. Efficacy of a replication-competent adenovirus (ONYX-015) following intratumoural injection: intratumoural spread and distribution effects. Cancer Gene Ther. 1999;6:499–504. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jain RK. Delivery of molecular medicine to solid tumours. Science. 1996;271:1079–1080. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5252.1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hecht JR, Bedford R, Abbruzzese JL, et al. A phase I/II trial of intratumoural endoscopic ultrasound injection of ONYX-015 with intravenous gemcitabine in unresectable pancreatic carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:555–561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mulvihill S, Warren R, Venook A, et al. Safety and feasibility of injection with an E1B-55 kDa gene-deleted, replication-selective adenovirus (ONYX-015) into primary carcinomas of the pancreas: a phase I trial. Gene Ther. 2001;8:308–315. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Apte MV, Park S, Phillips PA, et al. Desmoplastic reaction in pancreatic cancer: role of pancreatic stellate cells. Pancreas. 2004;29:179–187. doi: 10.1097/00006676-200410000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vonlaufen A, Joshi S, Qu C, et al. Pancreatic stellate cells: partners in crime with pancreatic cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2008;68:2085–2093. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Choi IK, Lee YS, Yoo JY, et al. Effect of decorin on overcoming the extracellular matrix barrier for oncolytic virotherapy. Gene Ther. 2010;17:190–201. doi: 10.1038/gt.2009.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dmitrieva N, Yu L, Viapiano M, et al. Chondroitinase ABC I-mediated enhancement of oncolytic virus spread and antitumour efficacy. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:1362–1372. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ganesh S, Gonzalez Edick M, Idamakanti N, et al. Relaxin-expressing, fiber chimeric oncolytic adenovirus prolongs survival of tumour-bearing mice. Cancer Res. 2007;67:4399–4407. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim JH, Lee YS, Kim H, et al. Relaxin expression from tumour-targeting adenoviruses and its intratumoural spread, apoptosis induction, and efficacy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:1482–1493. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tralhao JG, Schaefer L, Micegova M, et al. In vivo selective and distant killing of cancer cells using adenovirus-mediated decorin gene transfer. FASEB J. 2003;17:464–466. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0534fje. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Etoh T, Himeno Y, Matsumoto T, et al. Oncolytic viral therapy for human pancreatic cancer cells by reovirus. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:1218–1223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kelly EJ, Hadac EM, Cullen BR, Russell SJ. MicroRNA antagonism of the picornaviral life cycle: alternative mechanisms of interference. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000820. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nakano K, Todo T, Chijiiwa K, Tanaka M. Therapeutic efficacy of G207, a conditionally replicating herpes simplex virus type 1 mutant, for gallbladder carcinoma in immunocompetent hamsters. Mol Ther. 2001;3:431–437. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2001.0303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Norman KL, Coffey MC, Hirasawa K, et al. Reovirus oncolysis of human breast cancer. Hum Gene Ther. 2002;13:641–652. doi: 10.1089/10430340252837233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reis CL, Pacheco JM, Ennis MK, Dingli D. In silico evolutionary dynamics of tumour virotherapy. Integr Biol (Camb) 2010;2:41–45. doi: 10.1039/b917597k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hasegawa K, Pham L, O’Connor MK, et al. Dual therapy of ovarian cancer using measles viruses expressing carcinoembryonic antigen and sodium iodide symporter. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:1868–1875. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Langfield KK, Walker HJ, Gregory LC, Federspiel MJ. Manufacture of measles viruses. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;737:345–366. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-095-9_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carlson SK, Classic KL, Hadac EM, et al. In vivo quantification of intratumoural radioisotope uptake using micro-single photon emission computed tomography/computed tomography. Mol Imaging Biol. 2006;8:324–332. doi: 10.1007/s11307-006-0058-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Penheiter AR, Griesmann GE, Federspiel MJ, et al. Pinhole micro-SPECT/CT for noninvasive monitoring and quantification of oncolytic virus dispersion and percentage infection in solid tumours. Gene Ther. 2012;19:279–287. doi: 10.1038/gt.2011.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.