Abstract

The effectiveness of any biomedical prevention technology relies on both biological efficacy and behavioral adherence. Microbicide trials have been hampered by low adherence, limiting the ability to draw meaningful conclusions about product effectiveness. Central to this problem may be an inadequate conceptualization of how product properties themselves impact user experience and adherence. Our goal is to expand the current microbicide development framework to include product “perceptibility,” the objective measurement of user sensory perceptions (i.e., sensations) and experiences of formulation performance during use. For vaginal gels, a set of biophysical properties, including rheological properties and measures of spreading and retention, may critically impact user experiences. Project LINK sought to characterize the user experience in this regard, and to validate measures of user sensory perceptions and experiences (USPEs) using four prototype topical vaginal gel formulations designed for pericoital use. Perceptibility scales captured a range of USPEs during the product application process (five scales), ambulation after product insertion (six scales), and during sexual activity (eight scales). Comparative statistical analyses provided empirical support for hypothesized relationships between gel properties, spreading performance, and the user experience. Project LINK provides preliminary evidence for the utility of evaluating USPEs, introducing a paradigm shift in the field of microbicide formulation design. We propose that these user sensory perceptions and experiences initiate cognitive processes in users resulting in product choice and willingness-to-use. By understanding the impact of USPEs on that process, formulation development can optimize both drug delivery and adherence.

Introduction

The HIV prevention field is intensively focused on the development of chemoprophylactic prevention technologies to reduce sexual transmission. Topical microbicides remain a critical component of this work.1–3 Ongoing studies continue to evaluate several topical microbicide candidates (both vaginal and rectal formulations)4–7 and are in various phases of development. There is cautious optimism regarding the population-level impacts and cost-effectiveness of efficacious microbicides.8–11 Yet even if highly efficacious, the public health impact of anti-HIV microbicides will depend on actual use (i.e., adherence) by at-risk individuals.12–16 That is, the ultimate effectiveness of any biomedical prevention technology to reduce HIV incidence will require both biological efficacy and behavioral adherence.

Biological efficacy of any biomedical prevention technology derives from the pharmacokinetic (PK) and pharmacodynamic (PD) performance of the active pharmaceutical ingredient(s) (APIs), as delivered by their dosage form and dosing regimen. APIs can be delivered to targeted tissues via a diverse set of dosage forms, including semisolids (e.g., gels), quick-dissolving films and tablets, and controlled release devices (e.g., intravaginal rings), as well as oral tablets (preexposure or postexposure prophylaxis).17–20 Each formulation will exhibit a range of performance characteristics that depends upon product constituents, rheological and other biophysical properties, and characteristics and behaviors of the user. Product “behavior” is an anthropomorphic term used with participant-evaluators to help them conceptualize the product's activity/performance in the vagina (i.e., what is does and where it goes).

Behavioral adherence is likely a function of characteristics of these formulations (and how the product behaves), as well as the demands of dosing regimens, and the lives and needs of users. Users must be able and willing to correctly implement specific instructions regarding dosing schedule and product application, as well as to tolerate product characteristics well enough to maintain use, in order to optimize product effectiveness. To maximize user uptake and maintain product use, it is critical that products be designed and developed with careful consideration of what users want to experience, or will tolerate, when using these HIV prevention products.

In the product development framework currently being utilized, user adherence and product acceptability have historically been assessed in the context of phase 1–3 clinical trials, in which microbicides are tested with human subjects to determine safety, dosing, effectiveness, and side effects.1,21–25 Product acceptability has typically been conceptualized as a lack of annoyances (e.g., no excessive product leakage) or, in some cases, has been inferred solely from high levels of reported product use. Whether or not a microbicide's acceptability is both necessary and sufficient for its biological success, it is clear that adherence to use is necessary. Product adherence has been traditionally assessed by patient self-report and leftover product counts. Many studies have reported high self-reported adherence rates (80–90%).21,26 However, when studies have included biological measures to deduce product adherence (i.e., blood tests to measure plasma levels of active drug), these studies have found evidence inconsistent with self-reports and suggesting substantially lower rates of adherence (23–29%).27 The discrepancies in adherence rates obtained by participant self-report versus those indicated by biological assays may be associated with the quality of participant recall, limitations of assay sensitivity/specificity, and/or less-than-perfect data collection methods.1,16,28 True adherence rates likely reflect some function of each of these, as well as other factors.16

The relatively low microbicide effectiveness rates in several clinical trials may have been, at least in part, associated with lack of adherence to product use.29–32 The CAPRISA 004 microbicide trial provides some support for the critical relationship between adherence and product effectiveness. In the CAPRISA 004 trial, those with the highest rates of adherence (>80%) had a 54% lower HIV incidence rate versus the placebo, while those with intermediate (50–80%) adherence had a 38% lower HIV incidence, and those with low (<50%) adherence had a 28% lower HIV incidence.1 These findings point to the obvious need to increase user adherence to gather meaningful data on the biological effectiveness of these products and, in turn, to have a long-term impact on the number of new HIV infections.

To increase adherence, we believe that the current adherence and acceptability framework must be expanded to include antecedents to a user's willingness to use a specific microbicide product. We utilized methods similar to sensory evaluation science33,34 to begin to understand an individual's physical sensations and experiences of a product, with the goal of translating this into the design and development of microbicides. Sensory evaluation science is critical to the food and cosmetic industries. The field explores how products feel to prospective users (e.g., how chocolate feels when it melts on the tongue35; how lotion feels on the skin36), and contributes to design and refinement of products that best meet user needs and demands.37 We demonstrate that similar conceptualizations and methods can be used to evaluate pericoital topical vaginal microbicides.38

Rheological and other biophysical properties, and product performance attributes that depend upon them (e.g., shear stresses on tissue surfaces, rates of formulation spreading), can be objectively considered in relation to physical sensations and user experiences. These formulation properties and performance characteristics are under the direct control of developers. An integrated understanding of these elements could facilitate design of microbicide products that both effectively deliver the microbicide API(s) and elicit user experiences that reinforce future use. That is, what users experience on a sensory level when they insert a vaginal formulation (e.g., gel, film, tablet, suppository) or device (e.g., intravaginal ring, diaphragm), engage in interim behaviors (e.g., walking, foreplay), and/or engage in coital activities may play a critical role in product use adherence. Attending to the user sensations and experiences elicited by a particular formulation or device (i.e., perceptibility) is a plausible strategy for rationally designing products that have the potential to optimize proper adherence and/or mitigate poor adherence. We define “perceptibility” as the objective measurement of user sensory perceptions (i.e., sensations) and experiences (USPEs) of formulation properties and performance during use.

The overall goal of Project LINK was to develop an integrated framework that captures the range of USPEs of vaginal gels in relation to application, ambulation, and sexual experiences. We aimed to explore how those sensations and experiences can be meaningfully understood with respect to biophysical properties and vaginal spreading performance characteristics of the products. We hypothesize that USPEs are governed in part by properties of the gels (those properties that also govern gel vaginal distribution and retention). Using formative qualitative data, we postulated a set of behavioral constructs and dimensions, and developed survey items to measure them within a set of four test gels. The original set of items generated from qualitative interviews was reduced through psychometric analyses, resulting in a subset of items containing the scales that are presented here. The gels were designed to have a range of properties that spans those anticipated for topical vaginal microbicide gels. We focus here on the development of scales that assess USPEs of specific product properties and performance characteristics. The scope of the present article is to describe this novel methodology and to propose that biophysical properties can be meaningfully linked with user sensory perceptions and experiences.

Materials and Methods

The overall study proceeded in three stages. In the first stage, female participants completed qualitative formulation evaluation sessions for each of two vaginal gels, Replens (Parke-Davis, Morris Plains, NJ) and the “universal placebo,” hydroxyethylcellulose (HEC; CONRAD, Arlington, VA).39 These products were chosen by the study's formulation science team because of their different but representative range of formulation properties being considered for development as topical microbicides. The intention of the qualitative formative work that preceded scale item development was to characterize the range of user sensory perceptions that could be reliably experienced by users, to identify the language they used to describe those experiences, and to use that language and those experiences to generate an initial pool of statements (i.e., items) that could be further revised and evaluated in scale development.

Initial psychometric evaluation of those items and users' responses to them was completed in stage 2. This resulted in a set of scales that captured salient elements of USPEs during and following application, ambulation, and sexual activity. We then postulated rheological performance measures and other biophysical properties that might parallel those user experiences in, and outside of, the body. In so doing, we sought to gain an understanding of the relationship between USPEs and the properties and performance measures that govern delivery of drug into the vaginal vault (i.e., gel spreading as a deterministic factor in drug transport from a gel into the vaginal environment40).

Using those hypotheses, the study's formulation science team then developed and selected a set of four gel formulations with a range of properties that spanned a reasonable parameter space of gels suitable for vaginal use. The focus was on rheological properties that govern gel spreading and retention—during expression from an applicator into the vagina, during ambulation, and during subsequent sexual activity. In this way, we sought a context that could reveal potential linkages between rheological and other biophysical properties and the user experience. In the third and final stage of the study, each of these four gel formulations was evaluated, as described below, and psychometrically validated Perceptibility Scales were finalized.

Participants

Study activities were conducted at two urban sites in the northeastern United States. Eligible participants were 18–45 years of age: they reported regular menstrual cycles of 24–34 days in average length and vaginal sex with a male sexual partner in the previous 12 months. Women were ineligible if they reported any of the following: being diagnosed with a sexually transmitted infection (STI) in the previous 12 months, being HIV positive, being pregnant or breastfeeding, a vaginal delivery or reproductive surgical procedure in the previous 3 months, or previous irritation from vaginal products or latex. All participants were asked to use condoms (male or female) for any vaginal sex within 4 days of the first session and for the remainder of their participation in the study, and to refrain from vaginal sex for 24 h before each session. In addition, women were asked to refrain from douching for 48 h before their first session and throughout the remainder of their participation. Women were compensated for their time and effort after each session.

Recruitment

Because the scope of the project was limited to proof of concept and scale development, participants were recruited with the intention of enrolling a sample of women that would represent a range of vaginal anatomy/physiology as a function of age and vaginal births (see Table 1), while emphasizing the epidemiological burden of HIV among women of childbearing age.41 Women over age 45 years were not studied because we postulated that changes in the vaginal environment that occur perimenopause or postmenopause may alter the user experience outcomes being studied.

Table 1.

Distribution of Sample by Age Range and Parity

| 18–29 years | 30–45 years | |

|---|---|---|

| No (0) vaginal deliveries | 103 | 34 |

| One or more (1+) vaginal deliveries | 22 | 45 |

Study participants were recruited via advertisements (e.g., posters and street outreach), recruitment sessions at community-based organizations, internet advertisements (e.g., Craigslist), the research team's future studies contact log (composed of women who had given permission to be contacted for similar studies), and word of mouth. During screening, researchers described study requirements and procedures, including risks and benefits. If the prospective participant met all eligibility criteria, she was scheduled for enrollment, at which time informed consent procedures were completed. All study procedures were approved by the local human subjects' protection review boards.

Procedures

Each participant enrolled and completed four formulation evaluation sessions, with a minimum of 5–7 days between sessions. The order in which each participant experienced each of the gels was randomly assigned. At each session, participants first observed and manipulated the gel in their hands, guided by specific scripted instructions from the research staff. They then responded to survey items with respect to their initial impressions of the formulation and its properties (data not presented here). The participant was then escorted to an examination room where she was verbally instructed in application, ambulation, and simulated coitus procedures: written instructions were also available. The research staff left the room prior to application. In the privacy of the examination room, the participant inserted the formulation into her vaginal canal using a standardized prefilled applicator (HTI Comfort Tip applicator: HTI Plastics, Lincoln, NE). She then ambulated about the examination room and completed simulated coitus with a condom-covered (nonlubricated) artificial phallus. Application, ambulation, and coital simulation activities took approximately 7 min: 1 min to apply, 2 min to ambulate, and 4 min to simulate coitus. Each participant then responded to survey items with respect to her application, ambulation, and simulation experiences. The behavioral survey and associated scale items were administered via Computer-Assisted Self-Interview (CASI) on a laptop computer.

Formulations

Four gel formulations were evaluated. These formulations were designed to exhibit differing biophysical properties that, in turn, would give rise to different rheological performance characteristics, such as rates of spreading along the vaginal canal. At present, there is no gold standard gel formulation composition for vaginal microbicides, and gels with varying compositions, properties, and volumes have been evaluated in clinical trials.1,21,26,42–48 A common denominator in many of the trials has been the use of a 3% HEC gel as the placebo39; the tenofovir gel currently in its third effectiveness trial has properties similar to this 3% HEC gel (though slightly more viscous; unpublished data). Using our understanding of the biophysics of gel distribution and spreading along the vaginal canal, we selected four gels with varying amounts of HEC and carbopol to achieve a range of rheological properties that would give rise to a range in predicted vaginal spreadability and retention. These included the 3% HEC placebo gel as the most spreadable gel, and three others exhibiting higher viscosity ranges and yield stresses. Each was given a color label (i.e., orange, yellow, purple, and green) to avoid primacy effects of A-B-C-D or 1-2-3-4. All gels were composed of GRAS (generally recognized as safe) ingredients. The primary constituents for each gel, along with their compositions, are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Composition and Selected Formulation Properties for Each of Four Semisolid Gel Formulations Evaluated

| Composition of the Gels (wt%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constituentsa | [Orange] 3% HEC | [Yellow] 1.25% carbopol | [Purple] 2% HEC; 1.73% carbopol | [Green] 3% HEC; 2.5% carbopol |

| Carbopol 974P | 0% | 1.25% | 1.73% | 2.5% |

| Hydroxyethylcellulose | 3.0% | 0% | 2.0% | 3.0% |

| Glycerol | 5.0% | 5.0% | 5.0% | 5.0% |

| Methylparaben | 0.15% | 0.15% | 0.15% | 0.15% |

| Propylparaben | 0.05% | 0.05% | 0.05% | 0.05% |

| Sodium hydroxide | As needed to pH | As needed to pH | As needed to pH | As needed to pH |

| Hydrochloric acid | As needed to pH | As needed to pH | As needed to pH | As needed to pH |

| Purified water | QS to 100% | QS to 100% | QS to 100% | QS to 100% |

| Sodium chloride | 0.195% | 0.195% | 0.195% | 0.195% |

| Selected Formulation Properties | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [Orange] 3% HEC | [Yellow] 1.25% carbopol | [Purple] 2% HEC; 1.73% carbopol | [Green] 3% HEC; 2.5% carbopol | |||||

| Formulation properties | Undiluted | Dilutedb | Undiluted | Dilutedb | Undiluted | Dilutedb | Undiluted | Dilutedb |

| Viscosity at 1 s−1 (Pa-s)c | 96 | 40 | 250 | 184 | 492 | 287 | 1,474 | 1,079 |

| Viscosity at 100 s−1 (Pa-s)d | 3.9 | 2.2 | 6.6 | 4.6 | 10.9 | 7.5 | 14.4 | 14.0 |

| Residual stress (Pa)e | 13 | 0 | 129 | 87 | 120 | 72 | 182 | 172 |

| Volume (ml) | 3.5 | 3.5 | 3.5 | 2 | ||||

| Area coatedf at 2.5 min (cm2) | 53 | 67 | 35 | 35 | 35 | 36 | 20 | 20 |

| Area coatedf at 6 min (cm2) | 57 | 76 | 35 | 36 | 35 | 37 | 20 | 20 |

Ingredients were added as preservatives (methylparaben, propylparaben), to adjust pH (sodium hydroxide, hydrochloric acid) and to ensure proper gelation (water, glycerin, sodium chloride). The final pH values of the gels were adjusted to 5.0–5.6 with sodium hydroxide.

Diluted with 20% vaginal fluid simulant: simulates an upper bound of expected dilution in vivo.53

Viscosity at 1 s−1: characteristic of gel flow along the vaginal canal.

Viscosity at 100 s−1: characteristic of coital activity.

Residual stress: estimate of yield stress.

Area coated: predicted area of the vaginal epithelium coated by gel correlates with distance spread along the canal from the site of gel insertion in the fornix. Values are given at representative times for gel use in this study: 2.5 min after gel insertion (which corresponds to having applied the gel and ∼near completion of the 2-min ambulation period); and 6 min after gel insertion (which corresponds to the time passage from application, ambulation, and ∼near completion of coital activity time).

HEC, hydroxyethylcellulose.

The orange, yellow, and purple gels were designed to spread relatively well along the vaginal canal (termed “spreading” gels). The purple gel had an initial viscosity that was much higher than the orange and yellow gels but, upon dilution (see below), the viscosity was comparable. Their applied volumes in this study were all 3.5 ml. This volume is less than the 4 ml used for the tenofovir gel in CAPRISA004, VOICE, and FACTS trials,1,44,47 but the same as the volume in a number of other trials.45,49 The green gel was designed to be more solid like, consistent with interest in the microbicide field at the time in high viscosity (“bolus”) gels that do not tend to spread.50,51 The applied volume of the green gel was 2 ml, also in accord with the notion that high viscosity gels could be applied in smaller volumes than spreading gels (e.g., the volume of the relatively high viscosity dapivirine gel in trials has been 2.5 ml52).

Gel properties were measured, including viscosity versus shear rate, and residual stress, on a controlled stress rheometer (TA Instruments AR 1500ex, New Castle, DE) using standard methods.40 Gels were measured whole (undiluted) and also after 20% dilution and mixing with vaginal fluid simulant.53 The latter was undertaken to account for affects of dilution by vaginal fluid in vivo that, while not well understood, will tend to reduce viscosity and residual stress and, therefore, increase spreadability and decrease retention.54–56 These data, together with applied gel volume, were input to a computational model of gel spreading along the vaginal canal,40 a process currently used in the evaluation and development of vaginal microbicide gels.40,50,51,57,58 Table 2 presents the salient formulation properties and computational predictions of coated vaginal surface area within the context of this protocol. These quantitative performance measures are factors that contribute to delivery of microbicide drugs to target tissues and fluids.40 For example, the area of contact of gel with the vaginal epithelial surfaces has an impact on the rate and amount of drug that is transported out of the gel and into the vaginal mucosa, where it may act to inhibit HIV infection. As another example, a residual stress acts to hold a gel in place, and thus will constrain initial spreading and the tendency to leak, as well as increase the amount of time available for drug transport.

Taking into account our understanding of the gel properties and consequent potentials for vaginal spreading as they may relate to USPE, we postulated the following contrasts across gels. The orange gel would tend to spread early and well along the vaginal canal because of its relatively low viscosity values and virtual absence of a residual stress. The orange gel was thus hypothesized to be the most likely to leak from the vaginal vault. Similarly, we hypothesized that a moderate viscosity and lower yield stress would be most correlated with perceptions of smoothness; thus orange would be more smooth than yellow. Conversely, the yellow gel has a higher viscosity and higher residual stress than the orange gel, and thus would have less of a tendency to flow (or leak) than the orange gel. Although the yellow gel's net coating distance along the vaginal canal is similar to that of the purple gel, the yellow gel's lower viscosity allowed us to hypothesize that it would initially flow more readily than the purple gel. The purple gel's higher viscosity but lower residual stress than the yellow gel allowed us to hypothesize that it would be more adhesive than the yellow gel. Finally, the properties of the green gel were the most distinct from the orange gel. Its high viscosity and high residual stress inhibit deformation and spreading. Even when applied at a smaller volume (2 ml) than the other three gels, the green gel was expected to be less affected by dilution than the other gels during the time span of the protocol. Therefore, it was expected to flow very little, if at all, along the vaginal canal, ultimately behaving more like a flexible solid than a flowing gel. Furthermore, we hypothesized that after dilution the higher viscosity gels (e.g., green and purple) would be stickier than the gels with lower viscosities.

Of note, conventional microbicide acceptability characteristics, such as smell, taste, and packaging,14,59–62 were intentionally not the focus in Project LINK; sensory perceptions and experiences as a function of use (perceptibility), and how those USPEs may correspond to formulation properties, were the target constructs for evaluation. Items primarily attempted to capture gel performance (elicited sensations, flow: referred to as “gel behavior”) in as objective a process as possible, limiting regard for cognitive judgment and opinion until later in the evaluation process.

Measures

Table 3 contains a listing of variable categories and scales completed by participants at each session. The Perceptibility Scales utilize a Likert scale response format developed in an earlier scale development study13,63–66 through intensive cognitive interviewing strategies: (1) do not agree at all, (2) agree a little, (3) agree somewhat, (4) agree a lot, (5) agree completely.

Table 3.

Variables Captured by Session

| Session | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survey section | Description of variables captured | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Demographic information | Age (eligibility criterion), ethnicity, race, household income | X | ||||

| Demographic and eligibility questions | Eligibility criteria: age, sexual and reproductive health history; latex allergy; contraceptive use | X | ||||

| Session update questions | Per session behavioral eligibility (e.g., following intersession rules) | X | X | X | X | |

| Vaginal product use | Types of products used; by formulation | X | ||||

| Partner identification | Number; type | X | X* | X* | X* | |

| Sex behavior with partner | Vaginal, anal and oral sex; condom/barrier use | X | X* | X* | X* | |

| Risk perception with partner | HIV risk perception; STD risk perception | X | X* | X* | X* | |

| Pregnancy intention | Pregnancy intention with respect to partner | X | X* | X* | X* | |

| Rank options | Perceived importance of products intended for various sexual and reproductive health purposes (e.g., HIV prevention, STI prevention, contraception, lubrication, etc.) | X | X* | X* | X* | |

| USPE: in mano | User sensory perceptions and experiences of the formulation when in the hands; scripted manipulations | X | X | X | X | |

| USPE: Application | User sensory perceptions and experiences of the formulation periapplication | X | X | X | X | |

| USPE: Ambulation | User sensory perceptions and experiences of the formulation periambulation | X | X | X | X | |

| USPE: Coital activity | User sensory perceptions and experiences of the formulation perisimulated coitus | X | X | X | X | |

| Preferences | User evaluation of the formulation (e.g., ability to use the product covertly or as a part of foreplay, etc.) | X | X | X | X | |

| Willingness to use | Willingness to use the formulation with respect to their reproductive and health needs (e.g., HIV prevention, STI prevention, contraception, lubrication, etc.) in the next 30 days | X | X | X | X | |

| Important microbicide characteristics (IMC)33 | User evaluation of important formulation characteristics | X | X | X | X | |

| Microbicide use self-efficacy (MUSE)35,40 | User's confidence in formulation use | X | X | X | X | |

| Postcoital leakage experiences | User sensory perceptions and experiences following the passage of time in the laboratory: e.g., formulation leakage | X | X | X | X | |

| Postsession leakage experiences | User sensory perceptions and experiences of leakage in the 4 h subsequent to session 1, 2, or 3 | X | X | X | ||

| End of study questions | User choice of formulation, considering their own USPEs and anticipated USPEs of sexual partner(s) (e.g., which formulation would they be willing to use for various reproductive and sexual health needs (e.g., HIV or STI prevention, contraception, lubrication, etc.) | X | ||||

X*: if, in the “Session Update Questions,” the participant identified a new/different partner since the last session, these items would be completed with respect to that new/different partner.

USPE, user sensory perception and experience; STD, sexually transmitted disease; STI, sexually transmitted infection.

Statistical analyses

All analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics 20.0. Descriptive analyses are presented on the participant characteristics. Internal validity analyses were conducted for each behavioral instrument used within each gel formulation using principal component analysis (PCA) to determine the degree to which each item was related to its associated scale in this sample, as measured by its specific loading value. The strength of each item loading (the correlation of the item to the overall scale of which it is an indicator) was the primary criterion used to determine whether a specific item should be included within a specific scale. Within a PCA, item loadings can have an absolute value between 0 and 1, with loadings above 0.6 considered very good.67 The reliability of each behavioral instrument used with each gel was examined using Cronbach's coefficient alpha statistic,68 a measure of internal consistency. Consistent with the analytic scheme proposed in the funded project, in which our primary goal was to directly compare each gel to every other gel to fully understand the complete parameter space of gel differences, we conducted our analyses at the individual gel level with a series of paired t-tests that examined the averaged scale item score differences for each behavioral instrument between each pair of gels. Conceptually, this allowed us to compare scale scores of two gels with their corresponding biophysical/rheological properties, to elucidate initial understandings regarding which properties most impact USPEs. Cohen's d statistic69 was used to quantify the effect size differences of the paired t-test comparisons. This statistic provides a standardized measure of differences in standard deviation units, with values of 0.2, 0.5, and 0.8 suggested by Cohen to define small, medium, and large effect sizes, respectively.

Results

Sample characteristics

Two hundred and twenty-one (221) women were enrolled in the final formulation evaluation study (stage 3). Of those, 204 (92.3%) women completed all four product evaluation sessions (see Table 4 for basic demographic characteristics). Relevant demographic characteristics, as well as distributions of the sample by age, parity, and race/ethnicity, on all those who enrolled and completed the study are presented in Tables 4 and 1.

Table 4.

Description of Sample

| Number of volunteers screened | 451 |

| Number of eligible volunteers (% eligible of screened) | 304 (67.4%) |

| Number of enrolled volunteers (% enrolled of eligible) | 221 (72.7%) |

| Number of completed participants (% completed of enrolled) | 204 (92.3%) |

| N=204 | |

|---|---|

| Basic demographics of participants who completed all four sessions | [n (%)] |

| Age | |

| Range | |

| 18–29 years | 125 (61.3) |

| 30–45 years | 79 (38.7) |

| Mean | |

| 28.9 years | |

| Vaginal deliveries | |

| 0 | 137 (67.2) |

| 1 | 24 (11.8) |

| 2+ | 43 (21.1) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Latina/Hispanic | 30 (14.7) |

| Race (regardless of Latina ethnicity) | |

| Black/African American | 32 (15.7) |

| Caucasian/white | 110 (53.9) |

| Asian | 4 (2) |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 4 (2) |

| Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander | 0 (0) |

| Other | 15 (7.4) |

| Multiracial | 39 (19.1) |

| Current use of hormonal contraceptives | 71 (34.8) |

| Ever diagnosed with an STD | 39 (19.1) |

| Yearly income ($) | |

| <15 K | 72 (35.3) |

| 15 – <36 K | 73 (35.8) |

| >36 K | 57 (27.9) |

| Missing | 2 (1) |

Internal validity analyses

The 8 sexual activity and 11 application and ambulation Perceptibility Scales are composed of items developed from USPE information gathered during in-depth interviews that explored theoretical dimensions of interest (e.g., application experience, leakage experiences, experiences related to the gel's potential for covert use and for impacting sexual pleasure). The scales examined in this study were based on previous exploratory dimensional analyses conducted using the stage 2 sample, and on a careful restructuring of the item sets to correspond to the timing of the specific gel behavior–user behavior interaction.

Within each of the sets of items comprising the Perceptibility Scales, analyses were first conducted to examine item response distributions, means, standard deviations, skew, and kurtosis. We then examined a one-dimensional solution for each of the participants' response sets to the 19 posited scales for each of the four gels that they experienced using PCA. For these analyses, we conducted a total of 76 separate PCAs, and the results provided strong support for the internal validity of each scale through associated high scale loadings and good internal consistency. There were a total of 38 items examined within the 8 sexual activity scales, and a total of 48 items within the 11 application and ambulation scales.

Table 5 presents application, ambulation, and sexual activity Perceptibility Scale names, the constructs each captures, the number of items in each scale, and the average item loadings and internal consistency coefficients across all four gels evaluated. The average PCA item loading values for the participants' responses to each of the 48 items of the application and ambulation scales ranged from 0.51 to 0.89, while the average PCA item loading values for each of the 38 items of the sexual activity scales for the four gels ranged from 0.57 to 0.93. The average coefficient alpha measure of internal consistency for 9 of the 11 application and ambulation scales was good to excellent and ranged from 0.76 to 0.87; it was 0.69 and in the acceptable range for one short three-item scale, and was borderline acceptable at 0.57 for one four-item scale. The average coefficient alpha measure of internal consistency for seven of the eight sexual activity scales was good to excellent and ranged from 0.76 to 0.92; it was 0.67 and in the acceptable range for one short three-item scale.

Table 5.

Application, Ambulation, and Sexual Activity Perceptibility Scales

| Perceptibility scale | Constructs captured | Number of items | Component loadings: average item loading (range) | Internal consistency (coefficient alpha): average across gels |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Application: leakage | Perceptions and experiences of leakage immediately upon application | 3 | 0.79–0.81 | 0.69 |

| Application: ease | Physical comfort, simplicity, and ease of the application process | 5 | 0.51–0.88 | 0.78 |

| Application: discreet-portable | Users' perceptions of the applicator (HTI Comfort Tip applicator; similar in size to a standard tampon applicator) can be used and carried discreetly | 3 | 0.80–0.83 | 0.72 |

| Application: product awareness | Physical sensations of the product in the vagina during and after application | 5 | 0.71–0.86 | 0.86 |

| Application: lack of product awareness | Users' lack of awareness of physical sensations of the product in the vagina during application and ambulation | 3 | 0.79–0.89 | 0.80 |

| Ambulation: product movement | Sensations of the product moving/flowing from fornix toward introitus during ambulation | 7 | 0.71–0.85 | 0.87 |

| Ambulation: leakage | Sensations of the product leaking out of the vagina during ambulation; perceptions of messiness during ambulation; sensations of the product having moved/flowed to the introitus by the end of ambulation | 6 | 0.68–0.82 | 0.86 |

| Ambulation: hygiene | Sensations of leakage after ambulation but before coital activity; perceptions of desire to engage in hygiene (wiping) prior to coital activity | 4 | 0.79–0.86 | 0.84 |

| Ambulation: stickiness | Sensations of intra- and extravaginal stickiness during ambulation and prior to coital activity | 3 | 0.86–0.88 | 0.82 |

| Ambulation: product awareness | User perceptions that the product felt natural/comfortable as time passed from application until immediately before coital activity; physical sensations of the product in the vagina changing with time | 4 | 0.53–0.80 | 0.57 |

| Ambulation: spreading behavior | Sensations and perceptions of the product distributing evenly in the vagina prior to coital activity; sensations of smoothness, moisture, lubricated and mixing with natural lubrication | 5 | 0.70–0.82 | 0.82 |

| Sex: initial penetration | Smoothness and lubricity at initial penetration | 3 | 0.78–0.93 | 0.85 |

| Sex: initial lubrication | Coating and lubricating sensations during the first few strokes of coitus | 5 | 0.81–0.89 | 0.92 |

| Sex: spreading behavior | Perceptions of ease of stroke and product spread as coital strokes continued | 3 | 0.76–0.87 | 0.76 |

| Sex: product awareness | Feeling the product intravaginally during coitus (feeling the product moving around in the vagina, feeling the product between the vaginal wall and the phallus) | 7 | 0.60–0.84 | 0.83 |

| Sex: perceived wetness | Feeling as though the product was covering the entire vagina by the end of coitus; sensations of wetness, as they would after having sex or having an orgasm | 3 | 0.66–0.85 | 0.67 |

| Sex: stimulating | Whether or not they felt the product enhanced sexual pleasure or stimulated them | 6 | 0.71–0.88 | 0.89 |

| Sex: messiness | Perceptions of the product feeling watery or leaking/dripping/messiness as coitus continued | 6 | 0.57–0.79 | 0.78 |

| Sex: leakage | Sensations of the product leaking out during and after coitus; sensation of the product close to the introitus by the time coitus was ending; sensation of product in the pubic hair after coitus; feeling the need to clean up after coitus | 5 | 0.58–0.88 | 0.77 |

Perceptibility Scales, ©2013.

The constructs each captures, the number of items in each scale, and the average item loadings and coefficient alphas across all four gels evaluated are given.

Gel discrimination comparisons

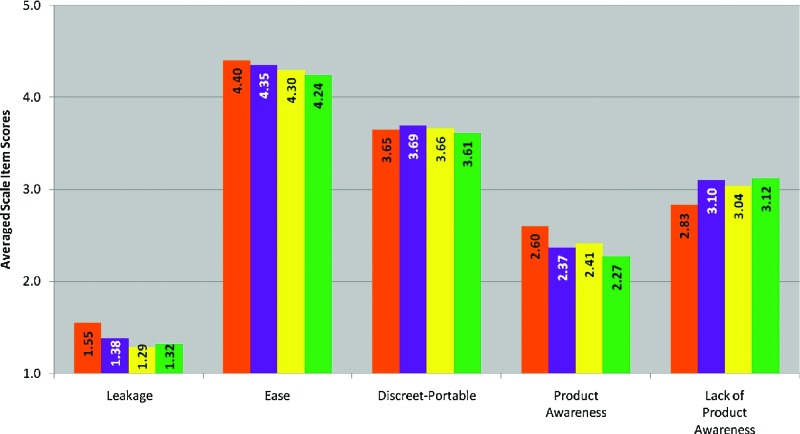

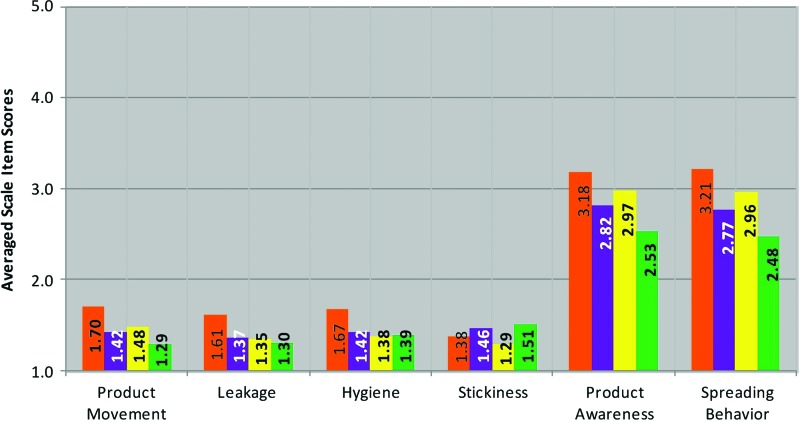

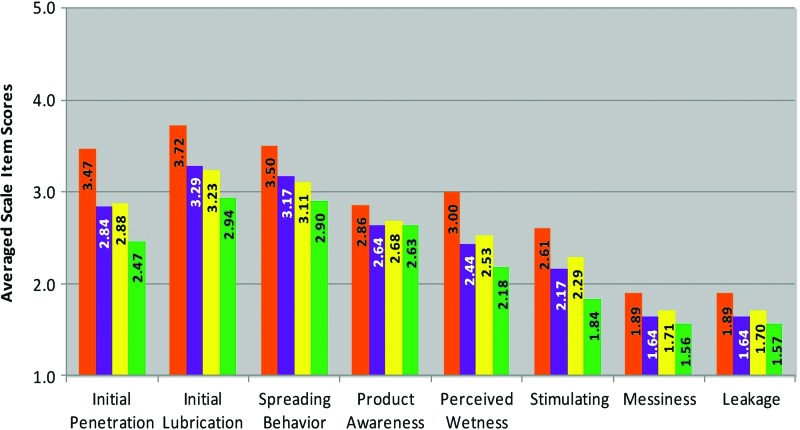

In pairwise comparisons, 10 of the 11 application/ambulation scales and each of the 8 sexual activity scales showed significant differences between one or more gel pairs. Figures 1–3 present averaged scale item scores and Table 6 presents Cohen's d (effect size) and p-value (significance level) for each pairwise comparison. Below, we will discuss only those of particular note in conceptualization.

FIG. 1.

Averaged scale items scores for each Perceptibility Scale for Application. 1=do not agree at all; 2=agree a little; 3=agree somewhat; 4=agree a lot; 5=agree completely. Primary constituents for each gel were 3% hydroxyethylcellulose (HEC) (orange); 1.25% carbopol (yellow); 2% HEC and 1.73% carbopol (purple); and 3% HEC and 2.5% carbopol (green). Pairwise comparisons are presented in Table 6. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/aid

FIG. 2.

Averaged scale items scores for each Perceptibility Scale for Ambulation. 1=do not agree at all; 2=agree a little; 3=agree somewhat; 4=agree a lot; 5=agree completely. Primary constituents for each gel were 3% hydroxyethylcellulose (HEC) (orange); 1.25% carbopol (yellow); 2% HEC and 1.73% carbopol (purple); and 3% HEC and 2.5% carbopol (green). Pairwise comparisons are presented in Table 6. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/aid

FIG. 3.

Averaged scale items scores for each Perceptibility Scale for Sexual Activity. 1=do not agree at all; 2=agree a little; 3=agree somewhat; 4=agree a lot; 5=agree completely. Primary constituents for each gel were 3% hydroxyethylcellulose (HEC) (orange); 1.25% carbopol (yellow); 2% HEC and 1.73% carbopol (purple); and 3% HEC and 2.5% carbopol (green). Pairwise comparisons are presented in Table 6. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/aid

Table 6.

Cohen's d (Effect Size) and p-Value (Significance Level) for Each Pairwise Comparison by Perceptibility Scale

| Gel Pair | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Orange-Yellow | Orange-Purple | Orange-Green | Yellow-Purple | Yellow-Green | Purple-Green | |||||||

| Perceptibility scale | d | p-value | d | p-value | d | p-value | d | p-value | d | p-value | d | p-value |

| Application perceptibility scales | ||||||||||||

| App: leakage | 0.40 | <0.001 | 0.24 | <0.05 | 0.34 | 0.001 | 0.14 | ns | 0.04 | ns | 0.10 | ns |

| App: ease | 0.20 | ns | 0.10 | ns | 0.33 | 0.001 | 0.11 | ns | 0.11 | ns | 0.22 | <0.05 |

| App: discreet-portable | 0.02 | ns | 0.07 | ns | 0.09 | ns | 0.05 | ns | 0.09 | ns | 0.15 | ns |

| App: product awareness | 0.26 | 0.01 | 0.27 | <0.01 | 0.4 | <0.001 | 0.05 | ns | 0.18 | ns | 0.12 | ns |

| App: lack of product awareness | 0.22 | <0.05 | 0.26 | <0.01 | 0.27 | <0.01 | 0.05 | ns | 0.02 | ns | 0.08 | ns |

| Ambulation perceptibility scales | ||||||||||||

| Amb: product movement | 0.38 | <0.001 | 0.46 | <0.001 | 0.75 | <0.001 | 0.12 | ns | 0.31 | <0.01 | 0.40 | <0.001 |

| Amb: leakage | 0.49 | <0.001 | 0.44 | <0.001 | 0.52 | <0.001 | 0.04 | ns | 0.11 | ns | 0.15 | ns |

| Amb: hygiene | 0.42 | <0.001 | 0.35 | 0.001 | 0.42 | <0.001 | 0.06 | ns | 0.01 | ns | 0.04 | ns |

| Amb: stickiness | 0.15 | ns | 0.12 | ns | 0.17 | ns | 0.29 | <0.01 | 0.33 | 0.001 | 0.08 | ns |

| Amb: product awareness | 0.35 | 0.001 | 0.61 | <0.001 | 1.11 | <0.001 | 0.25 | <0.05 | 0.76 | <0.001 | 0.52 | <0.001 |

| Amb: spreading behavior | 0.36 | <0.001 | 0.66 | <0.001 | 1.07 | <0.001 | 0.30 | <0.01 | 0.79 | <0.001 | 0.48 | <0.001 |

| Sexual activity perceptibility scales | ||||||||||||

| Sexa: initial penetration | 0.65 | <0.001 | 0.65 | <0.001 | 1.09 | <0.001 | 0.04 | ns | 0.43 | <0.001 | 0.38 | <0.001 |

| Sex: initial lubrication | 0.56 | <0.001 | 0.48 | <0.001 | 0.82 | <0.001 | 0.07 | ns | 0.30 | <0.01 | 0.36 | <0.001 |

| Sex: spreading behavior | 0.46 | <0.001 | 0.38 | <0.001 | 0.71 | <0.001 | 0.06 | ns | 0.39 | <0.01 | 0.33 | <0.001 |

| Sex: messiness | 0.29 | <0.01 | 0.38 | <0.001 | 0.52 | <0.001 | 0.11 | ns | 0.28 | <0.01 | 0.16 | ns |

| Sex: perceived wetness | 0.54 | <0.001 | 0.60 | <0.001 | 0.81 | <0.001 | 0.11 | ns | 0.42 | <0.001 | 0.32 | <0.001 |

| Sex: product awareness | 0.24 | <0.05 | 0.29 | <0.01 | 0.31 | <0.01 | 0.06 | ns | 0.07 | ns | 0.01 | ns |

| Sex: leakage | 0.29 | <0.01 | 0.39 | <0.001 | 0.49 | <0.001 | 0.26 | ns | 0.028 | ns | 0.25 | ns |

| Sex: stimulating | 0.38 | <0.001 | 0.57 | <0.001 | 1.01 | <0.001 | 0.15 | ns | 0.57 | <0.001 | 0.46 | <0.001 |

“Sex” or “sexual activity” refers to penetrative intercourse (in this study, simulated vaginal intercourse with a condom-covered [nonlubricated] artificial phallus [see Materials and Methods]).

ns, nonsignificant at alpha=0.05.

Application and ambulation scales

The experiences represented by the application (App:) and ambulation (Amb:) Perceptibility Scales occurred during the first approximately 0–3 min of use (application 0–1 min; ambulation for 2 min thereafter [timed]). As would be expected, the App: Discreet-Portable scale showed no significant differences between gel pairs, since the same applicator was used for all test gels. While the App: Ease scale elicited the highest levels of agreement overall (all gels had averaged scale item scores greater than 4, “agree a lot”), the lower agreement for the green gel suggests that its higher viscosity may have required the user to use greater force to push the plunger through the applicator barrel than did the other three gels.

The only gels that did not differ with respect to sensations of product movement during ambulation (Amb: Product Movement scale) were the purple and yellow gels. Data suggest that by the end of ambulation, the yellow, purple, and green gels did not differ from each other with respect to leakage, but the orange gel showed significant differences when compared to each of the other three gels, with user ratings averaging closer to “agree a little” than the other three gels. Overall, data suggest that users were unaware of movement with the green gel, but experienced some movement with the orange, yellow, and purple gels. As would be expected given the lower residual stress of the orange gel, this movement seems to have resulted in some users experiencing leakage by the time the ambulation period was over.

The yellow gel was the least sticky (Amb: Stickiness scale), while the green and purple gels (which have the highest viscosity when whole) were the most sticky according to the averaged scale item scores. The Amb: Product Awareness scale captures users' perceptions that the product feels like their natural experience (or starts to feel natural across time). There were significant differences noted between each of the gel pairs, thus each gel differed from every other gel in this regard. The greatest discrepancy was between the orange and the green gels, with greater endorsement of product awareness with the orange gel. The greatest difference in the Amb: Spreading Behavior scale, as was hypothesized given the rheological properties of the gels, was between the orange and the green gels.

Sexual activity scales

With respect to user sensory perceptions and experiences early in the coital simulation experience, significant differences were noted between user experiences with the orange gel and each of the other three formulations. The orange gel elicited the highest scores for smoothness and lubricity (Sex: Initial Penetration), coating and lubricating sensations during the first few strokes of coitus (Sex: Initial Lubrication), and sensations of ease of stroke and product spread throughout the vagina (Sex: Spreading Behavior). The green gel elicited significantly different scores versus orange and the other two formulations, but had the lowest averaged scale item scores.

Patterns changed somewhat in the pairwise comparisons for the Sex: Product Awareness scale. In these comparisons, users were most aware of the orange formulation. All three of the remaining formulations scored only slightly lower in agreement, and scores did not differ from each other. Thus, users did not quite reach the level of feeling that any of the formulations were highly detectable by themselves, nor did they believe their partners would be able to detect them. This is possibly an indication of a formulation's potential for covert use.

With respect to the Sex: Perceived Wetness scale, overall agreement was generally in a lower range. However, the pattern noted above continued, with the orange formulation eliciting the highest level of vaginal coating sensations by the end of simulation, as well as the highest scores for wetness. The Sex: Stimulating scale scores presented the same comparison patterns, but the scores were low, indicating little agreement among users that any of the formulations elicited sensations or experiences that were perceived as sexually stimulating, or that the users would consider increased their sexual pleasure.

The final two scales, Sex: Messiness and Sex: Leakage, are notable in that they were the lowest of the averaged scale item scores across all formulations and all scales, with the exception of the green formulation score on the Sex: Stimulating scale. Thus users were least likely to agree that any of the formulations were messy or leaked from the vagina during or after simulation (i.e., up to ∼1 h postcoital activity). The orange gel still received scores significantly higher than each of the other gels. With respect to messiness during sexual activity, the yellow gel was significantly more messy than the green formulation. When women returned for a subsequent evaluation session, they were asked to report on experiences in the hours following their previous session, specifically regarding leakage. The orange formulation had the highest levels of agreement to leakage queries (2.5), followed by yellow (2.2), then green (1.8), and purple (1.8).

Of note, the greatest effect sizes (Cohen's d) in the pairwise comparisons were found between averaged scale item scores for the orange and green formulations. Also of note is that the purple and yellow formulations did not differ with respect to any of the sexual activity Perceptibility Scales, effectively eliciting the same responses by users.

Discussion

Topical semisolid vaginal formulations such as gels elicit a complex set of sensations, perceptions, and experiences among users. In the present study, we operationalized gel “behavior” as the product's activity and/or performance in the vagina (i.e., what is does, and where it goes). The sensory perceptions and experiences, elicited by gel behaviors, appear to depend, at least in part, on sets of rheological and other biophysical properties of the formulations, which also govern gel distribution along the vaginal canal and over the external genitalia. Users' sensory perceptions and experiences of gel behaviors, in turn, will likely impact the use of the gels as prevention products.

In the current study, the test gels were chosen to exhibit a range of biophysical properties and rheological performance characteristics. Notably, women were able to perceive and report on differences in the distinct vaginal gel formulations that meaningfully correspond with gel properties. In addition, we were able to successfully explain aspects of the user experience based, in part, on our knowledge of gel properties and how those properties interact with each other and with endogenous fluids in the vaginal lumen. There are complex, multivariate, nonlinear relationships between gel properties and flow, and between properties/flow and sensory perceptions, and computational estimates of spreading behavior contributed to these explanations.40 The Perceptibility Scales developed in this study provide preliminary support for the link between gel properties and user sensory perceptions and experiences. Post-hoc analyses are underway that attempt to identify patterns in user experience and prediction of willingness-to-use as a function of these patterns.

With respect to the Perceptibility Scales, principal component analysis demonstrated that the scales derived (in stage 2) for application, ambulation, and simulated coitus had good internal validity. The scales not only demonstrated good psychometrics, but differences in scale scores between the four contrasting gels were meaningfully related to various gel properties and performance measures. For example, women were able to perceive and report on higher levels of leakage in the orange gel, which had the lowest viscosity and residual stress and, thus, was expected to leak out of the vaginal canal most readily. We also found that, overall, the average scale scores were most discrepant for the orange and green comparisons, which corresponds to the orange and green products having the largest differences in measures of gel properties and spreading. This is the first study to develop discrete user sensory perception and experience measures, and to begin to demonstrate the associations between vaginal gel properties and women's sensory perceptions of those products, and to introduce a novel methodology for assessing and utilizing USPEs.

It is hoped that in this new paradigm, we will gain a more nuanced understanding of how users experience product properties such as viscosity and residual stress. This can translate into rational product design very early in the development pipeline, before embarking on large-scale human trials with immutable—and potentially unacceptable—formulations. With this goal in mind, we make two recommendations regarding integration of perceptibility research into microbicide development.

First, we recommend broadening the current development framework to include perceptibility as a precursor to product choice and adherence. We believe that user sensory perceptions and experiences (i.e., perceptibility) of vaginal formulations are likely to be critical in the ultimate effectiveness of vaginal microbicides. A potent drug in a product with optimal PK and PD is the primary target for developers; however, the importance of the interplay between the product and the user is without question.

Results of the current study suggest some flexibility in achieving the PK/PD targets of developers across the spectrum of formulation and microbicide drug variability. Note that the purple and yellow formulations, differing by primary constituents and viscosity, did not differ with respect to any of the sexual activity perceptibility outcomes, effectively eliciting the same responses by users. If biological efficacy requires a less viscous gel that does not leak (e.g., a target product profile for a pericoital gel), the yellow gel, with its lower viscosity for more immediate spreading and its higher residual stress to minimize leakage, would seem to be a reasonable choice. On the other hand, if developers require a formulation that resides in the vaginal vault for many hours (to ensure adequate drug concentrations in the vaginal mucosa), then the purple gel, with its higher viscosity and a residual stress profile that minimizes leakage across time, could be preferable (either for a daily dosing regimen or for a dosing several hours before sexual intercourse). These are scenarios we plan to explore in follow-up studies.

Second, we recommend integrating perceptibility research into the preclinical product development pathway. Once the product formulations have moved past the preclinical laboratory and animal studies and into phase 1–3 human trials, their material compositions and properties are largely fixed. We propose that in order to make a significant impact in creating products that are likely to elicit user experiences that optimize use, these types of perceptibility evaluations must be incorporated into the preclinical product development pipeline. This could be undertaken with products that are devoid of drugs. It would require that prototype formulations have rheological and other biophysical properties that are duplicated in the bioactive products. Minor adjustments to excipient concentrations might be necessary (e.g., to achieve drug solubility in the clinical product), but this would likely not alter safety and stability concerns. For example, questions as basic as appropriate gel volume could be addressed here. At this early stage in product development, there is an opportunity to alter product formulation details (including volume)—that are objectively designed to achieve optimal PK and PD—to also meet a range of users' needs and preferences.

We believe that the behavioral methodology presented here, integrated with the biophysical methodology, can lead to an objective, novel, and beneficial framework to facilitate the design of effective vaginal microbicide gels. However, there are some limitations. First, while there are many statistically significant differences across the four formulations with respect to various use-associated experiences, until formulations characterized by these properties are evaluated in real-life settings, we cannot determine whether small, medium, or large effect sizes (i.e., Cohen's d) are necessary for “clinical significance.”

Second, within the scope of this article, we are not able to interpret which perceptions and experiences most impact users' decision making with respect to future product use. Indeed, our primary goal was to develop the tools to use in such studies (i.e., Perceptibility [USPE] Scales). Follow-up analyses are underway to begin the process of relating USPEs to product choice; however, given the complex nature of gel properties and user experience, it is likely that no single experience of these formulations can explain user choice. Indeed, a mosaic of experiences may best explain a user's choice of formulation and preferences may vary based on culture and other demographic factors. Understanding these patterns of experience and their relationship to choices that users make will allow for targeted marketing of future products to specific populations.

Third, the current study is limited in its sole use of vaginal semisolid (i.e., gel) formulations outside of the context of a real-life sexual episode. The microbicide field specifically, and the sexual and reproductive health field more broadly, should consider perceptibility across a range of potential drug delivery systems, as well as various sexual practices (e.g., anal sex). Products currently being developed, including vaginal films and tablets, intravaginal rings, and barrier devices, should also consider preclinical perceptibility (USPE) evaluations. Devices such as rings would likely require distinct variables to characterize their material properties and biomechanical performance characteristics. In addition, in vivo studies of actual coital experiences would shed light on the ability of women to perceive product properties in the context of a typical sexual experience. Additionally, the user experiences of sexual partners could be considered, both in terms of partners' own sensory perceptions and experiences of various formulations—and the choices elicited by those experiences—and in terms of the relative influence of partners based on relationship context.

Finally, it will be important for behavioral scientists and microbicide formulation designers and developers to ascertain what factors outside of rheological performance characteristics and other biophysical properties drive user experience and choices. These could include dosing frequency, coital association (or not), user characteristics such as age, vaginal delivery history, or hormonal contraceptive use, and USPE preferences of users' sexual partners. They could also include those factors long associated with more conventional psychosocial conceptualizations of microbicide acceptability, such as product color, scent, taste, and packaging.

Summary and Conclusions

We have developed a set of user sensory perception and experience (USPE: perceptibility) scales that demonstrates good psychometric properties and that reveals potential links between biophysical properties and users' experiences of vaginal gels. While these results are promising, they are preliminary. Still, the formative work presented here offers a novel and potentially paradigm-shifting approach to vaginal product development. It provides a methodological structure and a set of perceptibility metrics that can be used to assess perceptibility parameters targeted during the preclinical design of candidate microbicide products. Admittedly, there is much to be done to develop an efficient strategy that integrates perceptibility into the current design processes of product developers. This will require the creation of design and evaluation protocols that can be implemented in standardized ways by product development teams.

Understanding the perceptibility of formulation properties and device characteristics within a preclinical framework, and discerning how perceptibility elicits user experiences and willingness to use various vaginal drug delivery systems, could lead to critical breakthroughs in designing biomedical prevention products that optimize adherence in clinical trials and eventual market use.

Contributor Information

Collaborators: The Project LINK Study Team

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the efforts of the Project LINK Study Team: Candelaria Barosso, Michelle Higgins, Jacquelyn Wallace, Lara Thompson, Dana Bregman, Jacob van den Berg, Kathleen Jensen, Shira Dunsiger, Anacecilia Panameño, Christopher Colleran (The Miriam Hospital, Providence, RI); Liz Salomon, Charles Covahey, Kenneth H. Mayer, Danielle Dang, Vanessa Frontiero, Lori Panther (Fenway Community Health Center, Boston, MA); Jennifer Peters, Anthony Geonnotti, Marcus Henderson, Bonnie Lai (Duke University, Chapel Hill, NC); Meredith Clark, Anthony Tuitupou, Judith Fabian (University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT). In addition, we would like to thank all of Project LINK's participants and the community-based organizations that facilitated recruitment efforts. Kathleen M. Morrow also acknowledges, and is grateful for, the generous contributions of our colleagues at HTI Plastics, Inc., Rip n Roll, and Good for Her, Inc. This project was funded by the National Institutes of Health's Microbicide Innovation Program award (NIH: R21/R33 MH080591) and CONRAD (PPA-09-023 under USAID Cooperative Agreement GPO-A-00-08-00005-00). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of CONRAD, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), or the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Abdool Karim Q, Abdool Karim SS, Frohlich JA, et al. : Effectiveness and safety of tenofovir gel, an antiretroviral microbicide, for the prevention of HIV infection in women. Science 2010;329(5996):1168–1174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Padian NS, Buve A, Balkus J, Serwadda D, and Cates WJ: Biomedical interventions to prevent HIV infection: Evidence, challenges, and way forward. Lancet 2008;372(9638):585–599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rotheram-Borus MJ, Swendeman D, and Chovnick G: The past, present, and future of HIV prevention: Integrating behavioral, biomedical, and structural intervention strategies for the next generation of HIV prevention. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 2009;5:143–167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McGowan I. and Dezzutti C: Rectal microbicide development. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 2013;April24 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Obiero J, Mwethera PG, Hussey GD, and Wiysonge CS: Vaginal microbicides for reducing the risk of sexual acquisition of HIV infection in women: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect Dis 2012;12(289):1471–2334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McGowan I: Microbicides for HIV prevention: Reality or hope? Curr Opinion Infect Dis 2010;26:26–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Obiero J, Mwethera PG, and Wiysonge CS: Topical microbicides for prevention of sexually transmitted infections. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;13(6): CD007961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Verguet S. and Walsh JA: Vaginal microbicides save money: A model of cost-effectiveness in South Africa and the USA. Sex Transm Infect 2010;86(3):212–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vickerman P, Watts C, Delany S, Alary M, Rees H, and Heise L: The importance of context: Model projections on how microbicide impact could be affected by the underlying epidemiologic and behavioral situation in 2 African settings. Sex Transm Dis 2006;33(6):397–405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Watts C. and Vickerman P: The impact of microbicides on HIV and STD transmission: Model projections. AIDS 2001;15:S43–S44 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Terris-Prestholt F: Model projections of the population-level impact, on HIV and herpes simplex virus type-2 (HSV-2) and cost-effectiveness of tenofovir gel, an antiretroviral microbicide. Paper presented at the XIX International AIDS Conference, July22–27, 2012, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Bruin M. and Viechtbauer W: The meaning of adherence when behavioral risk patterns vary: Obscured use- and method-effectiveness in HIV-prevention trials. PLoS One 2012;7(8):31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morrow K, Rosen R, Vargas S, Barroso C, Kiser P, and Katz D: User-identified vaginal gel characteristics: A qualitative exploration of perceived product efficacy. Paper presented at the International Microbicides 2010 Conference, May24, 2010, Pittsburgh, PA [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morrow KM. and Ruiz MS: Assessing microbicide acceptability: A comprehensive and integrated approach. AIDS Behav 2008;12(2):272–283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thurman AR, Clark MR, and Doncel GF: Multipurpose prevention technologies: Biomedical tools to prevent HIV-1, HSV-2, and unintended pregnancies. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol 2011;2011:1–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tolley EE, Harrison PF, Goetghebeur E, et al. : Adherence and its measurement in phase 2/3 microbicide trials. AIDS Behav 2010;14(5):1124–1136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baeten JM, Donnell D, Ndase P, et al. : Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV prevention in heterosexual men and women. N Engl J Med 2012;367(5):399–410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, et al. : Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med 2011;365(6):493–505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grant RM, Lama JR, Anderson PL, et al. : Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. N Engl J Med 2010;363:2587–2599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Landovitz RJ. and Currier JS: Clinical practice. Postexposure prophylaxis for HIV infection. N Engl J Med 2009;361(18):1768–1775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abdool Karim SS, Richardson BA, Ramjee G, et al. : Safety and effectiveness of BufferGel and 0.5% PRO2000 gel for the prevention of HIV infection in women. AIDS 2011;25(7):957–966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carraguard Phase II South Africa Study Team: Expanded safety and acceptability of the candidate vaginal microbicide carraguard in South Africa. Contraception 2010;82(6):563–571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Greene E, Batona G, Hallad J, Johnson S, Neema S, and Tolley EE: Acceptability and adherence of a candidate microbicide gel among high-risk women in Africa and India. Cult Health Sex 2010;12(7):739–754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kamali A, Byomire H, Muwonge C, et al. : A randomised placebo-controlled safety and acceptability trial of PRO 2000 vaginal and microbicide gel in sexually active women in Uganda. Sex Transm Infect 2010;86(3):222–226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kilmarx PH, van de Wijgert JH, Chaikummao S, et al. : Safety and acceptability of the candidate microbicide Carraguard in Thai Women: Findings from a Phase II clinical trial. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2006;43(3):327–334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McCormack S, Ramjee G, Kamali A, et al. : PRO2000 vaginal gel for prevention of HIV-1 infection (Microbicides Development Programme 301): A phase 3, randomised, double-blind, parallel-group trial. Lancet 2010;376(9749):1329–1337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Microbicide Trials Network: Daily HIV prevention approaches didn't work for African Women in the VOICE Study 2013; www.mtnstopshiv.org/node/4877

- 28.McGowan I, Gomez K, Bruder K, et al. : Phase 1 randomized trial of the vaginal safety and acceptability of SPL7013 gel (VivaGel) in sexually active young women (MTN-004). AIDS 2011;25(8):1057–1064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adams JL. and Kashuba ADM: Formulation, pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of topical microbicides. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2012;26(4):451–462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marrazzo J, Ramjee G, Nair G, et al. :. Pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV in women: Daily oral tenofovir, oral tenofovir/emtricitabine, or vaginal tenofovir gel in the VOICE Study (MTN 003). Paper presented at The Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI), 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shihata AA. and Brody SA: HIV prevention by enhancing compliance of tenofovir microbicide. Using a novel delivery system. HIV AIDS Rev 2010;9(4):105–108 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Simoni JM, Kurth AE, Pearson CR, Pantalone DW, Merrill JO, and Frick PA: Self-report measures of antiretroviral therapy adherence: A review with recommendations for HIV research and clinical management. AIDS Behav 2006;10(3):227–245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hootman RC: Manual on Descriptive Analysis Testing for Sensory Evaluation. ASTM International, West Conshohocken, Pennsylvania, 1992 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meilgaard M, Civille GV, and Carr BT: Sensory Evaluation Techniques, 3rd ed. CRC Press LLC, Boca Raton, FL, 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ziegler G, Mongia G, and Hollender R: The role of particle size distribution of suspended solids in defining the sensory properties of milk chocolate. Int J Food Prop 2001;4(2):353–370 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marty JP, Lafforgue C, Grossiord JL, and Soto P: Rheological properties of three different vitamin D ointments and their clinical perception by patients with mild to moderate psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2005;19(s3):7–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.DeMartine ML. and Cussler EL: Predicting subjective spreadability, viscosity, and stickiness. J Pharm Sci 1975;64(6):976–982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mahan ED, Morrow KM, and Hayes JE: Quantitative perceptual differences among over-the-counter vaginal products using a standardized methodology: Implications for microbicide development. Contraception 2011;84(2):184–193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tien D, Schnaare RL, Kang F, et al. : In vitro and in vivo characterization of a potential universal placebo designed for use in vaginal microbicide clinical trials. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2005;21(10):845–853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Katz DF, Gao Y, and Kang M: Using modeling to help understand vaginal microbicide functionality and create better products. Drug Deliv Transl Res 2011;1(3):256–276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC): HIV among Women, 2011

- 42.Bunge K, Macio I, Meyn L, et al. : The safety, persistence, and acceptability of an antiretroviral microbicide candidate UC781. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2012;60(4):337–343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.ClinicalTrials.gov An Expanded Safety Study of Dapivirine Gel 4789 in Africa, 2013; http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT00917904

- 44.FACTS Consortium FACTS 001 Study, 2011; http://factsconsortium.wordpress.com/facts-001-study/

- 45.Haaland RE, Evans-Strickfaden T, Holder A, et al. : UC781 microbicide gel retains anti-HIV activity in cervicovaginal lavage fluids collected following twice-daily vaginal application. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2012;56(7):3592–3596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mascolini M: HIV Prevention Fails in All Three VOICE Arms, as Daily Truvada PrEP Falls Paper presented at the 20th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, March3–6, 2013, Atlanta, GA [Google Scholar]

- 47.Microbicide Trials Network Fact Sheet Results—Understanding the Results of VOICE. 2013; www.mtnstopshiv.org/node/2003

- 48.Skoler-Karpoff S, Ramjee G, Ahmed K, et al. : Efficacy of Carraguard for prevention of HIV infection in women in South Africa: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2008;372(9654):1977–1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.El-Sadr W, Mayer K, Maslankowski L, et al. : Safety and acceptability of cellulose sulfate as a vaginal microbicide in HIV-infected women. AIDS 2006;20(8):1109–1116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kiser PF, Mahalingam A, Fabian J, et al.: Design of Tenofovir-UC781 combination microbicide vaginal gels. J Pharm Sci 2012;101(5):1852–1864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mahalingam A, Smith E, Fabian J, et al. : Design of a semisolid vaginal microbicide gel by relating composition to properties and performance. Pharm Res 2010;27(11):2478–2491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nel AM, Smythe SC, Habibi S, Kaptur PE, and Romano JW: Pharmacokinetics of 2 dapivirine vaginal microbicide gels and their safety vs. hydroxyethyl cellulose-based universal placebo gel. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2010;55(2):161–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Owen DH. and Katz DF: A vaginal fluid simulant. Contraception 1999;59(2):91–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lai BE, Xie YQ, Lavine ML, Szeri AJ, Owen DH, and Katz DF: Dilution of microbicide gels with vaginal fluid and semen simulants: Effect on rheological properties and coating flow. J Pharm Sci 2008;97(2):1030–1038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tasoglu S, Katz DF, and Szeri AJ: Transient spreading and swelling behavior of a gel deploying an anti-HIV topical microbicide. J Nonnewton Fluid Mech 2012;188:36–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tasoglu S, Peters JJ, Park SC, Verguet S, Katz DF, and Szeri AJ: The effects of inhomogeneous boundary dilution on the coating flow of an anti-HIV microbicide vehicle. Phys Fluids 2011;23(9):93101–931019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mahalingam A, Simmons AP, Ugaonkar SR, et al. : Vaginal microbicide gel for delivery of IQP-0528, a pyrimidinedione analog with a dual mechanism of action against HIV-1. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2011;55(4):1650–1660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ham AS, Ugaonkar SR, Shi L, et al. : Development of a combination microbicide gel formulation containing IQP-0528 and tenofovir for the prevention of HIV infection. J Pharm Sci 2012;101(4):1423–1435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jogelkar N, Joshi S, Kakde M, et al. : Acceptability of PRO2000 vaginal gel among HIV un-infected women in Pune, India. AIDS Care 2007;19(6):817–821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ramjee G, Morar NS, Braunstein S, Friedland B, Jones H, and van de Wijgert J: Acceptability of Carraguard, a candidate microbicide and methyl cellulose placebo vaginal gels among HIV-positive women and men in Durban, South Africa. AIDS Res Ther 2007;4:20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bentley ME, Fullem AM, Tolley EE, et al. : Acceptability of a microbicide among women and their partners in a 4-country phase I trial. Am J Pub Health 2004;94(7):1159–1164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rosen RK, Morrow KM, Carballo-Dieguez A, et al. : Acceptability of tenofovir gel as a vaginal microbicide among women in a phase I trial: A mixed-methods study. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2008;17(3):383–392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fava JL, van den Berg JJ, Rosen RK, et al. : Measuring self-efficacy to use vaginal microbicides: The microbicide use self-efficacy instrument. Sex Health 2013;28(10):339–347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Morrow K, Fava J, Kiser P, Rosen R, and Katz D: The LINK between gel properties and user perceptions: Implications for rational design of microbicides. Paper presented at the International Microbicides 2010 Conference, May23, 2010, Pittsburgh, PA [Google Scholar]

- 65.Morrow KM, Fava JL, Rosen RK, Christensen AL, Vargas S, and Barroso C: Willingness to use microbicides varies by race/ethnicity, experience with prevention products, and partner type. Health Psychol 2007;26(6):777–786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Morrow KM, Fava JL, Rosen RK, et al. : Willingness to use microbicides is affected by the importance of product characteristics, use parameters, and protective properties. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2007;45(1):93–101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Comrey AL. and Lee HB: A First Course in Factor Analysis, 2nd ed. Lawrence Erlbaum, Hillsdale, NJ, 1992 [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cronbach LJ: Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 1951;16:297–334 [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cohen J: Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed. Lawrence Erlbaum, Hillsdale, NJ, 1988 [Google Scholar]