Abstract

Glioblastoma (GBM) proliferation is a multistep process during which the expression levels of many genes that control cell proliferation, cell death, and genetic stability are altered. MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are emerging as important modulators of cellular signaling, including cell proliferation in cancer. In this study, using next generation sequencing analysis of miRNAs, we found that miR-127-3p was downregulated in GBM tissues compared with normal brain tissues; we validated this result by RT-PCR. We further showed that DNA demethylation and histone deacetylase inhibition resulted in downregulation of miR-127-3p. We demonstrated that miR-127-3p overexpression inhibited GBM cell growth by inducing G1-phase arrest both in vitro and in vivo. We showed that miR-127-3p targeted SKI (v-ski sarcoma viral oncogene homolog [avian]), RGMA (RGM domain family, member A), ZWINT (ZW10 interactor, kinetochore protein), SERPINB9 (serpin peptidase inhibitor, clade B [ovalbumin], member 9), and SFRP1 (secreted frizzled-related protein 1). Finally, we found that miR-127-3p suppressed GBM cell growth by inhibiting tumor-promoting SKI and activating the tumor suppression effect of transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) signaling. This study showed, for the first time, that miR-127-3p and its targeted gene SKI, play important roles in GBM and may serve as potential targets for GBM therapy.

Introduction

Glioma is the most common primary tumor in the brain and is categorized into four clinical grades on the basis of histology and prognosis. Grade IV GBM is the most malignant of all brain tumors, and the 5-year survival rate is dismal (Vescovi et al., 2006). Alterations in signal transduction pathways such as TGF-β signaling contribute to GBM initiation and progression (Joseph et al., 2013). TGF-β signaling plays important roles in tumorigenesis by functioning either in tumor suppression or promotion. Most members of the TGF-β signaling pathway are known to be targeted by one or more miRNAs (Butz et al., 2012).

MiRNAs are endogenous, small, noncoding RNAs, ranging in size from 20 to 25 nt, that function as post-transcriptional regulators of gene expression through their interaction with the 3′ untranslated region (3′UTR) of target mRNAs (Filipowicz et al., 2008). MiRNAs are well known to participate in cell proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis. For example, miR-21, as an important oncogene, promotes multiple important components of TGF-β signaling because downregulation of miR-21 in GBM cells leads to reduction of TGF-β signaling, causing repression of growth, increased apoptosis, and cell cycle arrest (Papagiannakopoulos et al., 2008). Additionally, miR-18a inhibits the transcription of CTGF (connective tissue growth factor) partially by reducing the protein expression and phosphorylation of Smad3 and the TGF-β signaling. Most importantly, miR-18 expression inversely correlates with the TGF-β signature, and miR-18 expressions are correlated with prolonged survival in GBM patients (Fox et al., 2013).

Here, we found that miR-127-3p was downregulated in GBM tissues compared with normal brain tissues and that simultaneous DNA demethylation and histone deacetylase inhibition resulted in downregulation of miR-127-3p in GBM cells. In addition, we demonstrated that miR-127-3p inhibits GBM cell growth by inducing G1-phase arrest both in vitro and in vivo. Furthermore, we showed that SKI (v-ski sarcoma viral oncogene homolog [avian]), RGMA (RGM domain family, member 1), ZWINT (ZW10 interacaator, kinetochore protein), SERPINB9 (serpin peptidase inhibitor, clade B [ovalbumin]), and SFRP1 (secreted frizzled-related protein 1) are the direct target genes of miR-127-3p. Finally, we found that miR-127-3p activated TGF-β signaling to suppress GBM cell growth by influencing the expression of SKI, TGFBR1 (transforming growth factor, beta receptor 1), and MYC (v-myc myelocytomatosis viral oncogene homolog [Avian]), as well as the phosphorylation of Smad3.

Materials and Methods

Human tissue samples

Tissue samples from 17 patients with GBM and 6 patients with other neurological diseases were collected after informed consent was obtained and approval was granted from the Institutional Ethics Committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Soochow University, Suzhou, China. All tissues were obtained at the time of surgery, verified by a pathologist, and immediately stored in liquid nitrogen until use.

Cell culture and reagents

The human GBM cell lines LN229 and T98G and the stably transfected cells LN229miR-con, LN229miR-127-3p, T98GmiR-con’, and T98GmiR-127-3p were grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum in a 5% CO2 humidified incubator at 37°C. MiR-127-3p inhibitors, which were single antisense sequences of miR-127-3p with a 2’-O-methyl modification, and their respective negative controls, were obtained from Ribobio Co. (Guangzhou, China). siRNAs against SKI and scrambled siRNA negative controls were synthesized by Ribobio Co.

Small RNA sequencing and data analysis

The construction of a small RNA sequencing library and Illumina sequencing were performed as described in our previous report (Hua et al., 2012). After sequencing, we aligned each sequence to the human miRNA precursor (Sanger miRBase 17.0) using BLAST (version 2.2.11). Raw abundance in the libraries was normalized according to the following formula: normalized abundance=raw abundance/total miRNA matched *1,000,000 (TPM: transcripts per million). Student's t-test was used to measure significant differences in expression.

PBA and 5-Aza-CdR treatments

LN229 cells were seeded in 6-well plates 24 h prior to treatment with 5-aza-2’-deoxycytidine (5-Aza-CdR) (0.1 μmol/L, 1 μmol/L or 3 μmol/L; Sigma-Aldrich) and 4-phenylbutyric acid (PBA) (0.1 mmol/L, 1 mmol/L or 3 mmol/L; Sigma-Aldrich). After 24 h, 5-Aza-CdR was removed, whereas PBA was continuously administered by replacing the medium with fresh medium containing PBA every 24 h for 5 days. DMSO-treated cells were used as controls, and each experiment was repeated three times.

DNA extraction, methylation-specific PCR and bisulfite-modified DNA sequencing

Genomic DNA was extracted from cultured cells using the DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (Qiagen). Genomic DNA (250 ng) was bisulfite-treated with the EZ DNA Methylation-GoldTM Kit (Zymo Research) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Methylation-specific PCR (MS-PCR) for miR-127-3p was performed using Zymo Taq™ DNA polymerase (Zymo Research) with the following primers: M forward, 5′-GTATTCGAAGGTTTTTTGTTTTTC-3′ M reverse, 5′-CCCTAACTCCAAACTATCTCTACGA-3′; U forward, 5′-GGTATTTGAAGGTTTTTTGTTTTTT-3′; U reverse, 5′-CCCCTAACTCCAAACTATCTCTACA-3′. For bisulfite-modified DNA sequencing, Zymo Taq™ DNA polymerase was used to amplify the miR-127-3p gene with the following primers: forward, 5′-TAGTTTGGAGTTAGGGGTAGGGTAT-3′; reverse, 5′-AATAAATCAAAAAAAACACCTCCAC-3′. The PCR products were gel-extracted, subcloned into a pMD®18-T vector (Takara), and transformed into Escherichia coli. Six colonies were randomly chosen for sequencing. Primers for both MSPCR and bisulfite PCR were designed using the MethPrimer web tool (http://www.urogene.org/cgi-bin/methprimer/methprimer.cgi).

Plasmid construction and transfection

The genomic sequence of the human miR-127-3p gene was cloned from the genomic DNA of LN229, inserted into pSUPER.neo (Oligoengine), and designated as pSUPER.neo-miR-127-3p. The 3′UTR segments of SKI, SFRP1, ZWINT, RGMA, and SERPINB9 were amplified by PCR from the genomic DNA of LN229 and cloned into the pmirGLO vector (Promega). Mutant 3′UTR segments of SKI, SFRP1, ZWINT, RGMA, and SERPINB9 were generated based on the TaKaRa MutanBEST Kit by mutating four nucleotides that are recognized by miR-127-3p. The coding sequence of SKI was synthesized and subcloned into the pcDNA3.1(+) vector (Genscript). All PCR products were verified by DNA sequencing. All primers for PCR are listed in Supplementary Table S1 (supplementary material is available online at www.liebertpub.com). Transfections were carried out using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Cell proliferation assay

Cells (2×103) were seeded in 96-well plates. On the following day, the cells were transfected with pSUPER.neo-miR-127-3p, vector control, pSUPER.neo-miR-127-3p+miR-127-3p inhibitor, the pSUPER.neo-miR-127-3p+miRNA inhibitor control, SKI siRNA, or the siRNA negative control. The DMEM (100 μL) containing 10% fetal bovine serum was changed at 6 hours post-transfection. Cell viability was measured using a Cell Counting Kit-8 (Dojindo) at 24, 48, 72, and 96 h after transfection. CCK-8 solution (10 μL) was added to each well, and the cultures were incubated at 37°C for 3 h. Finally, the optical density was measured with a microplate spectrophotometer at a wavelength of 450 nm. The results are presented as the mean values of three separate experiments.

Colony formation assay

For the colony formation assay, cells were seeded in 6-well plates. On the following day, the cells were transfected with pSUPER.neo-miR-127-3p or the control vector, and untreated cells were used as the blank control. At 48 h after transfection, the medium was replaced with fresh medium containing G418 (1 mg/mL) to kill untransfected cells. The cells were grown for 14 days prior to fixation with methanol for 30 min at room temperature and staining with 0.1% crystal violet. The colonies were then counted by microscopy. All assays were repeated three times.

Apoptosis and cell cycle analysis

For apoptosis and cell cycle analyses, the cells were harvested and washed with PBS, followed by fixation with 70% ethanol overnight at −20°C. After washing three times in PBS, the cells were resuspended in 0.979 mL of PBS solution with 1 μL of Triton X-100, 20 μg of PI, and 200 μg of DNase-free RNase for 30 min at room temperature in the dark. The samples were then analyzed to determine their DNA content by flow cytometry (BD FACSCantoII). The apoptosis and cell-cycle phases were analyzed using FACSDiva software (v6.1.3).

Orthotopic transplants

All animal experiments were approved by the institutional animal care committee. Five-week-old female nude mice were anesthetized, and LN229miR-con or LN229miR-127-3p cells (3.5×104 in 3 μL of PBS) were stereotactically implanted in the putamen region (1 mm anterior and 2.5 mm lateral to the Bregma at a depth of 3.5 mm). The mice were monitored for recovery until complete wakening. The animals were sacrificed 8 weeks after tumor implantation. The brains were removed, sectioned, and stained with H&E. Maximal tumor cross-sectional areas were measured by computer-assisted image analysis.

MiRNA target prediction

Target genes of miR-127-3p were predicted using five algorithms: PicTar (http://pictar.mdc-berlin.de), TargetScan (http://www.targetscan.org), miRDB (http://mirdb.org), DIANA (http://diana.cslab.ece.ntua.gr), and MiRanda (http://www.microrna.org). The genes in the predicted target list were then filtered based on their overlap with downregulated genes identified in the microarray comparison between LN229miR-127-3p and LN229miR-con. The array data were submitted to the GEO database (GSE50173).

RNA isolation and real-time PCR analysis

For mRNA analysis, reverse transcription was performed by using M-MLV reverse transcriptase (Promega). Amplification reactions were performed using SYBR® Premix Ex Taq™ (TaKaRa). The data were normalized to the level of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) expression in each sample. Expression of miR-127-3p was quantified using stem-loop RT-PCR analysis. All reagents for stem-loop RT-PCR were obtained from Ribobio Co. (Guangzhou, China). U6 RNA was used as an internal control. The 2-ΔΔCT method for relative quantification of gene expression was used to determine the expression levels of the transcripts. All primers are listed in Supplementary Table S2.

Luciferase assay

LN229 cells were transiently transfected with the luciferase reporter gene constructs and the miR-127-3p-expressing plasmid. After 48 h, luciferase activity was measured using a dual luciferase reporter assay system according to the manufacturer's protocol (Promega). For each plasmid construct, three independent transfection experiments were performed in triplicate.

Western blot analysis

The cells were lysed using RIPA buffer supplemented with protease inhibitors (Calbiochem), and the protein concentration was estimated using the Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Scientific). Equal amounts of protein were separated by electrophoresis on 12% SDS-PAGE gels and transferred onto PVDF membranes, which were then blocked for 1.5 h in 5% skim milk in TBST. The membranes were then incubated with primary and secondary antibodies as indicated, and the proteins were detected using the ECL system (Thermo Scientific). The antibodies used in these assays included anti-SFRP1 (5467-1, Epitomics; 1:10000); anti-SKI (sc-9140, Santa Cruz Biotechnology; 1:1000); anti-RGMA (sc-46484, Santa Cruz Biotechnology; 1:500); anti-ZWINT (sc-67362, Santa Cruz Biotechnology; 1:500); anti-SERPINB9 (sc-71897, Santa Cruz Biotechnology; 1:10); anti-GAPDH (ab9483, Abcam; 1:5000); anti-TGFBR1 (3712S, Cell Signaling; 1:500); anti-Smad3 (1735-1, Epitomics; 1:5000); anti-Smad3 Phospho (1880-1, Epitomics; 1:1000); anti-MYC (M20002, Abmart; 1:500); rabbit anti-goat IgG HRP (RAG007, MultiSciences; 1:5000); goat anti-rabbit IgG HRP (GAR007 MultiSciences; 1:5000); and goat anti-mouse IgG HRP (GAM007, MultiSciences; 1:5000).

Statistical analysis

The results are reported as the mean±SD. Statistical analysis was performed using Student's t-test. A p value <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

MiR-127-3p is significantly downregulated in GBM and is highly induced by DNA demethylation and histone deacetylase inhibition.

Using next generation sequencing, we analyzed the miRNA profiles of four GBM and four normal brain tissues, and we found that miR-127-3p was significantly downregulated (p<0.005) in GBM tissues compared with normal brain tissues (Fig. 1A). To confirm the observed differential miR-127-3p expression, we further analyzed the expression of miR-127-3p in 17 individual GBM samples and 6 individual normal brain tissues by quantitative RT-PCR. The results showed that the expression of miR-127-3p was significantly downregulated (p=0.032) in GBM tissues compared with normal brain tissues (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 1.

MiR-127-3p is significantly downregulated in GBM tissues. (A) MiRNA-seq analysis of 4 GBM (G1–G4) and 4 normal brain tissues (N1—N4). Y-axis, reads per million from the next generation sequencing data. (B) MiR-127-3p expression in 6 normal brain tissues (N, white columns) and 17 GBM tissues (G, black columns) was measured by stem-loop RT-PCR. U6 small nuclear RNA was used as an internal control. Student's t test was used to examine differences in miR-127-3p levels between normal brain tissues and GBM tissues (p=0.032).

MiR-127-3p maps to a region on chromosome 14 between two LincRNAs (ENSG00000214548 and ENSG00000258399). This region overlaps with a strong CpG island (36 CpGs), and it is embedded within the gene RTL1 (retrotransposon-like 1) (http://genome.ucsc.edu). We hypothesized that miR-127 may be regulated via promoter methylation and histone deacetylase. Therefore, we first analyzed miR-127-3p expression levels in LN229 cells treated with 5-Aza-CdR and PBA, which inhibit DNA methylation and histone deacetylase, respectively. As shown in Figure 2A, miR-127-3p was upregulated approximately three-fold after treatment with a combination of 3 μmol/L 5-Aza-CdR and 3 mmol/L PBA; however, it showed no significant difference in the presence of either one of the two drugs alone. Next, we examined the DNA methylation status of the promoter region of the miR-127-3p gene before and after 5-Aza-CdR and PBA treatment by MS-PCR and bisulfite genomic sequencing. We found that the methylation level of the miR-127-3p promoter decreased from 60% to 27% after 5-Aza-CdR and PBA treatment in LN229 cells (Fig. 2B and 2C).

FIG. 2.

The MiR-127-3p expression is induced by DNA demethylation and histonedeacetylase inhibition. (A) MiR-127-3p is highly induced by 5-Aza-CdR and PBA treatment. LN229 cells were treated with 5-Aza-CdR and/or PBA, and the miR-127-3p expression level was analyzed by stem-loop RT-PCR. U6 small nuclear RNA expression was used as an internal control. 0.1A, 0.1 μmol/L 5-Aza-CdR; 1A, 1 μmol/L 5-Aza-CdR; 3A, 3 μmol/L 5-Aza-CdR; 0.1P, 0.1 mmol/L PBA; 1P, 1 mmol/L PBA; 3P, 3 mmol/L PBA; 0.1AP, combination of 0.1 μmol/L 5-Aza-CdR and 0.1 mmol/L PBA; 1AP, combination of 1 μmol/L 5-Aza-CdR and 1 mmol/L PBA; 3AP, combination of 3 μmol/L 5-Aza-CdR and 3 mmol/L PBA. The data obtained from three independent experiments are shown as the mean±SD (*p<0.05). (B) MS-PCR data showing the differential methylation states in the promoter region of the miR-127-3p gene in LN229 cells treated (or not) with 5-Aza-CdR (3 μmol/L) and PBA (3 mmol/L). U and M indicate PCR reactions using MSP-PCR primers specific for unmethylated and methylatedDNAs, respectively. (C) The DNA methylation status of the promoter region of the miR-127-3p gene in LN229 cells treated (or not) with 5-Aza-CdR (3 μmol/L) and PBA (3 mmol/L) was determined byPCR-cloning andbisulfite sequencing. Each row represents a single clone that was sequenced (white circles: unmethylatedCpG; black circles: methylatedCpG).

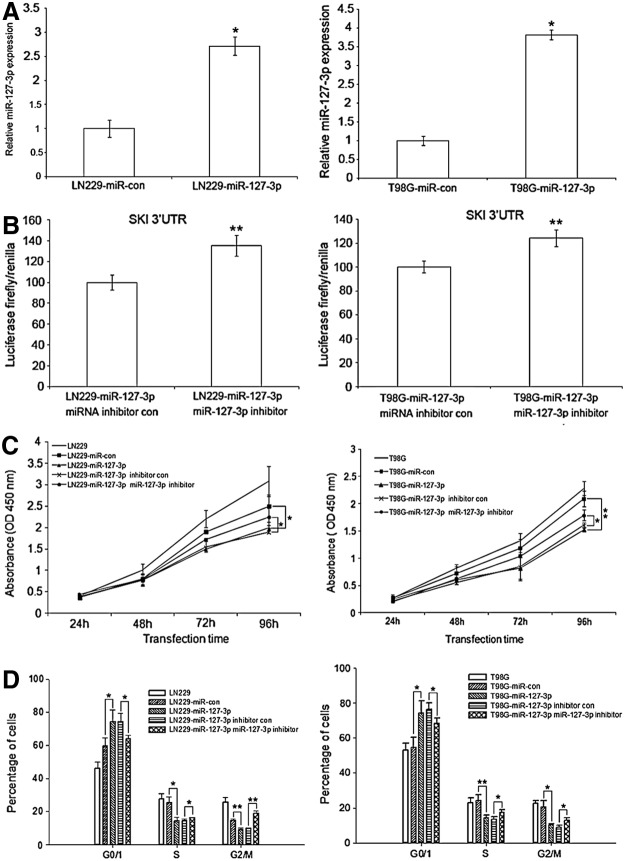

MiR-127-3p inhibits GBM cell growth

The silencing of miR-127-3p in GBM tissues prompted us to investigate whether miR-127-3p functions as a tumor suppressor in GBM. Transfection of pSUPER.neo-miR-127-3p restored the expression of miR-127-3p in the GBM cell lines LN229 and T98G (Fig. 3A), and the miR-127-3p inhibitors decreased the activity of miR-127-3p (Fig. 3B), as measured by the relative activity of a luciferase reporter construct (PmirGLO) containing target sites for miR-127-3p of the 3’UTR of SKI that was co-transfected with pSUPER.neo-miR-127-3p and its inhibitor or pSUPER.neo-miR-127-3p and controls (no inhibitors) in LN229 cells. Restoration of miR-127-3p expression in the GBM cell lines LN229 and T98 repressed cell growth (Fig. 3C). At 96 h after transfection, there was a significant difference (p<0.05) between LN229 or T98G cells overexpressing miR-127-3p and their respective controls (p=0.038 for LN229 and p=0.003 for T98G). Simultaneously, there was a significant difference (p<0.05) between the LN229 or T98G cells overexpressing miR-127-3p and the cells transfected with miR-127-3p inhibitors (p=0.037 for LN229 and p=0.047 for T98G). Furthermore, restoration of miR-127-3p expression in the GBM cell line inhibited cell cycle progression (Fig. 3D). In both LN229 and T98G cells, high levels of miR-127-3p expression resulted in a higher percentage of cells in the G0/G1 phase (p=0.045 for LN229 and p=0.021 for T98G), a smaller fraction in the S phase (p=0.011 for LN229 and p=0.009 for T98G), and a smaller fraction in the G2/M phase (p=0.004 for LN229 and p=0.010 for T98G). In contrast, LN229 and T98G cells overexpressing miR-127-3p that were treated with miR-127-3p inhibitor had lower proportions of cells in the G0/G1 phase (p=0.033 for LN229 and p=0.043 for T98G) with a higher fraction in the S phase (p=0.046 for LN229 and p=0.038 for T98G) and a higher fraction in the G2/M phase (p=0.001 for LN229 and p=0.038 for T98G) compared with LN229 and T98G cells overexpressing miR-127-3p, respectively. However, altering the expression of miR-127-3p had no measurable effect on the apoptosis of GBM cells (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

MiR-127-3p inhibits GBM cell growth in vitro. (A) MiR-127-3p expression in LN229 and T98G cells transiently overexpressing miR-127-3p was detected using stem-loop RT-PCR, and U6 small nuclear RNA was used as an internal control. The data are presented as the mean±SD; *p<0.05. (B) PmirGLO, a dual-luciferasemiRNA target expression vector containing the 3′UTR of SKI, was transfected into LN229 or T98G cells containing miR-127-3p and miR-127-3p inhibitors or their respective negative controls. After 48 h, firefly luciferase activity was measured and normalized to renillaluciferase activity. The results are presented as the mean of three independent experiments±SD; **p<0.01. (C) At 24, 48, 72, and 96 h after transfection, cell proliferation was determined using the CCK-8 assay. The data are presented as the mean±SD of three independent experiments; *p<0.05; **p<0.01. (D) The cells were stained using PI and Annexin-V at 72 h post-transfection and analyzed by FACS. The cell cycle distribution was calculated. The results are presented as the average of three separate experiments (mean±SD); *p<0.05; **p<0.01.

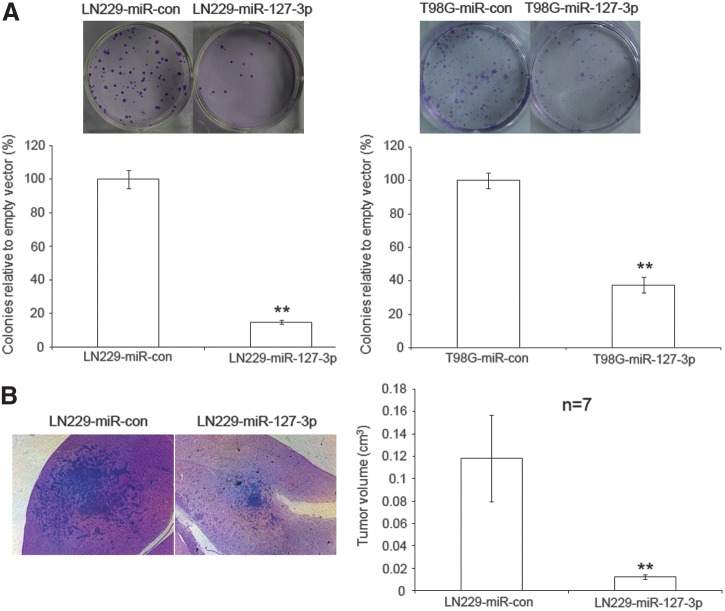

We next examined the effects of miR-127-3p expression on colony formation and in vivo animal studies. We found that miR-127-3p overexpression inhibited colony formation in both LN229 and T98 cells (p<0.01) (Fig. 4A). In animal studies, LN229miR-con or LN229miR-127-3p cells were implanted intracranially into the putamen region of the brain of nude mice (n=7), and tumor volumes were measured after 8 weeks. We found that xenografts generated with LN229miR-127-3p cells were significantly smaller than those generated with LN229miR-con cells (p<0.01) (Fig. 4B). Therefore, miR-127-3p overexpression inhibited the in vivo growth of human GBM cells in nude mice.

FIG. 4.

MiR-127-3p decreases GBM cell colony formationin vitro and inhibits GBM cell growth in vivo. (A) A colony formation assay was performed using LN229 and T98G cells transfected with pSUPER.neo-miR-127-3p or pSUPER.neo-miR-con and selected in media containing 1 mg/mL G418 for 14 days. The colonies were stained with crystal violet and photographed, and the results were quantified by determining the average number of colonies obtained in each transfection reaction relative to pSUPER.neo-miR-con (which was set at 100%). The results are presented as the mean values of three independent experiments±SD; **p<0.01. (B) H&E stained brain sections produced 8 weeks after intracranially implanting LN229miR-127-3p or LN229miR-con into the brains of nude mice (n=7). Magnification=40X. Tumor sizes were measured, and a statistically significant difference was observed between the control and miR-127-3p groups; **p<0.01.

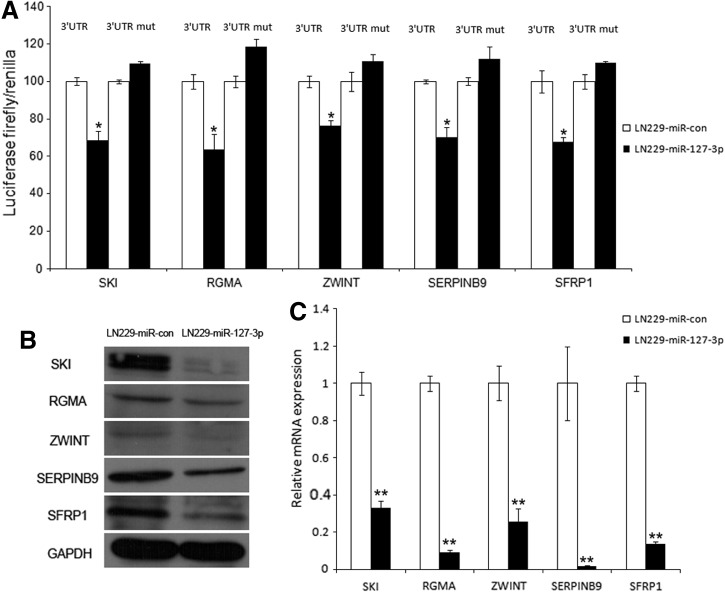

MiR-127-3p targets SKI, RGMA, ZWINT, SERPINB9, and SFRP1

The target genes of miR-127-3p were predicted using five algorithms as described in Materials and Methods. To select the top candidate genes, we first filtered the list based on overlap with downregulated genes from the microarray comparison between LN229miR-127-3p and LN229miR-con (GEO submission GSE50173). The genes identified from the microarray experiment that contain a predicted site for miR-127-3p is listed in Supplementary Table S3. We then selected genes that were related to tumors based on their GO annotations and a literature review. Subsequently, we cloned the 3′UTRs of 10 putative miR-127-3p targets (Supplementary Table S4) into a luciferase construct. Luciferase assays with miR-127-3p-expressing LN229 cells revealed that miR-127-3p repressed the activity of five genes: SKI, RGMA, ZWINT, SERPINB9, and SFRP1. Mutating the putative miR-127-3p site in the 3′UTRs of these five genes abrogated their responsiveness to miR-127-3p (Fig. 5A). Furthermore, miR-127-3p decreased the protein (Fig. 5B) and cellular mRNA levels of these five targets in LN229 cells (Fig. 5C).

FIG. 5.

MiR-127-3p targets SKI, RGMA, ZWINT, SERPINB9, and SFRP1. (A) Luciferase activity assay demonstrating direct targeting of the 3′UTR of SKI, RGMA, ZWINT, SERPINB9, and SFRP1 by miR-127-3p. LN229 cells were transfected with pSUPER.neo-miR-127-3p and the pmirGLO vector containing the 3′UTR (the first and second columns) or the 3’UTR-mut (the third and fourth columns) of SKI, RGMA, ZWINT, SERPINB9, and SFRP1. After 48 h, firefly luciferase activity was measured and normalized to renillaluciferase activity. The results are presented as the mean values of three independent experiments±SD; *p<0.05. (B) Western blot analysis was performed to examine the expression of SKI, RGMA, ZWINT, SERPINB9, and SFRP1 proteins in LN229 cells transfected with pSUPER.neo-miR-127-3p and the control vector. (C) In parallel, the mRNA expression levels in LN229 cells treated as described in (B) were measured by real time RT-PCR. GAPDH was used as the internal control. The data are presented as the mean±SD; **p<0.01.

MiR-127-3p activates TGF-β signaling by targeting SKI in GBM

Based on comparative expression profiling of LN229miR-con and LN229miR-127-3p cells, we identified ten differentially expressed genes belonging to TGF-β signaling pathways (Supplementary Fig. S1A). Real time RT-PCR confirmed the differential expression of these genes (Supplementary Fig. S1B). SKI is an important negative regulator of TGF-β signaling by binding to the SMAD proteins and blocking the ability of the SMAD complexes to activate TGF-β signaling in many types of tumors (Deheuninck and Luo, 2009). Therefore, we investigated whether TGF-β signaling was involved in the antitumor effect of miR-127-3p by targeting SKI.

We found that either overexpression of miR-127-3p or knockdown of SKI increased the expression of TGFBR1, promoted the phosphorylation of Smad3, and decreased the expression of MYC in both LN229 and T98G cells. Moreover, overexpression of SKI decreased the expression of TGFBR1, inhibited the phosphorylation of Smad3, and increased the expression of MYC in LN229miR-127-3p and T98GmiR-127-3p cells stably overexpressing miR-127-3p (Fig. 6A and 6B).

FIG. 6.

MiR-127-3p activates TGF-β tumor suppresser pathway by inhibiting SKI expression in GBM cells. (A) LN229 cells were transfected with pSUPER.neo-miR-127-3p or SKI siRNA or cotransfected with pSUPER.neo-miR-127-3p and pcDNA3.1(+)-SKI. The expression levels of of GAPDH (internal control), SKI, TGFBR1, Smad3, phosphorylated Smad3, and Myc were detected by Western blot. (B) T98G cells were transfected as described in (A), and the expression of the indicated proteins was detected by Western blot. (C) LN229 cells were transfected with SKI siRNA. At 24, 48, 72, and 96 h after transfection, cell proliferation was detected and analyzed. The data are presented as the mean±SD of three independent experiments. (D) LN229 cells were transfected as described in (C), and after 72 h, the cell cycle distribution was calculated. The results are presented as the average of three separate experiments (means±SD).

We further determined that knockdown of SKI in GBM LN229 cells repressed cell growth (Fig. 6C) and inhibited cell cycle progression (Fig. 6D), which was similar to the effect of miR-127-3p restoration on the cell growth and cell cycle of GBM cells (Fig. 2C).

Discussion

Here, we have shown for the first time that miR-127-3p expression is decreased in GBM tissues compared with normal brain tissues (Fig. 1). However, we were unable to obtain a matched set of normal and primary GBM tissues; therefore, we were not able to show that miR-127-3p was silenced in GBM primary tissues compared with the matched normal brain tissues. We further showed that the CpG island in the promoter region of miR-127-3p was highly methylated in GBM cells by MS-PCR and bisulfate genomic sequencing (Fig. 2), suggesting that promoter methylation might be the cause of the decreased miR-127-3p expression in GBM tissues. Saito et al. examined the expression of a miR-127 cluster in a panel of cancer cell lines (HCT116, HeLa, NCCIT, Ramos, CFPAC-1, MCF7, and CALU-1), two normal human fibroblast cell lines (LD98 and CCD-1070Sk), and paired sets of normal tissues and primary prostate, bladder, and colon cancer tumors (Saito et al., 2006). They found that miR-127 was silenced in the cancer cells but expressed in normal cells and further showed that miR-127 expression was substantially induced by the chromatin-modifying drugs 5-Aza-CdR and PBA in a dose-dependent manner in HCT116, HeLa, NCCIT, and Ramos cells (Saito et al., 2006). We also performed a similar experiment and showed that miR-127-3p was significantly induced after treatment with 5-Aza-CdR and PBA (Fig. 2), which is consistent with the findings of Saito et al., (2006). Saito et al. showed that only a combination of the DNA-demethylating agent 5-Aza-CdR and the histone deacetylase inhibitor PBA could induce miR-127 expression in cancer cells, whereas each compound alone did not produce an effect (Saito et al., 2006). We therefore treated the GBM cells with both reagents instead of either single reagent alone (Fig. 2). Cameron et al. (1999) showed that both reagents were needed to maximize the effect of epigenetic modification reversal for genes with densely methylated DNA associated with transcriptionally repressive chromatin characterized by the presence of underacetylated histones.

We showed that restoration of miR-127-3p expression in GBM cells suppressed proliferation and blocked the G1/S transition, whereas suppression of miR-127-3p enhanced proliferation and promoted the G1/S transition (Fig. 3). Moreover, miR-127-3p overexpression inhibited the in vivo growth of human GBM cells in nude mice (Fig. 4). These data appear to suggest that miR-127-3p functions as a tumor suppressor. Our data are consistent with a recent publication by Guo et al. (2013) showing that ectopic expression of miR-127 in the gastric cancer cell line HGC-27 inhibits cell proliferation, cell cycle progression, and cell migration and invasion.

Although Saito et al. (2006), Guo et al. (2013), and our group have shown that miR-127 expression is downregulated in GBM as well as gastric, prostate, bladder, and colon cancers, other groups have observed that miR-127-3p expression was higher in acute myeloid leukemia (Dixon-McIver et al., 2008), esophageal squamous cell carcinomas (Zhang et al., 2010), and cervical cancers (Lee et al., 2008). These data provide support for the hypothesis that the function of miR-127 is cancer type-specific.

We also demonstrated for the first time that miR-127-3p targets five genes: SKI, RGMA, ZWINT, SERPINB9, and SFRP1 (Fig. 5), thus expanding the list of validated target genes of miR-127. The proto-oncogenes BCL6 (B-cell CLL/lymphoma 6) and MAPK4 (mitogen-activated protein kinase 4) were previously shown to be targets of miR-127 (Guo et al., 2013; Saito et al., 2006).

Using the TCGA data, we analyzed the miR-127 expression with the survival of GBM patients, but did not find a significant association between the two. We also performed a survival analysis using the Rembrandt databases for the five target genes of miR-127: SKI, RGMA, ZWINT, SERPINB9, and SFRP1. We found only one gene whose expression is significantly associated with patient survival, considering only p<0.01 as significant. We found that SFRP1 expression seemed to be associated with glioma patient survival (log-rank p-value of 2.86E-5, downregulated vs. all other gliomas) (Supplementary Fig. S2).

SKI has been implicated in various types of cancers including gastric cancer (Kiyono et al., 2009; Takahata et al., 2009), colorectal cancer (Bravou et al., 2009), and melanoma (Chen et al., 2003; Lin et al., 2010b), but its roles as a promoter or a repressor is dependent on its interactions with protein complexes and on the cellular context. In melanoma cells, Lin et al. showed that SKI binds to receptor-activated Smads (including pSmad2/3-C proteins) in the nucleus, forming repressor complexes containing HDACs, mSin3, NCoR, and other protein partners (Lin et al., 2010b). However, Lin et al. also found that SKI could promote Smad3 linker (Samd3L) phosphorylation that results in the switch of TGF-β from tumor suppressor to oncogenic functions in melanoma cells (Lin et al., 2010b). In pancreatic cancer, Wang et al. (2009) showed that Ski might act as a tumor proliferation-promoting factor or as a metastatic suppressor in human pancreatic cancer. In gastric cancers, SKI and MEL1 cooperate to inhibit transforming growth factor-beta signal by stabilizing the inactive Smad3-SKI complex on the promoter of TGF-β target genes (Takahata et al., 2009).

To the best of our knowledge, the role of SKI in glioma has not yet been studied. The current study provides the first evidence that SKI plays a role in GBM. We demonstrated that knockdown of SKI increased the expression of TGFBR1 and promoted the phosphorylation of SMAD3 (Fig. 6), resulting in activation of the TGF-β signaling pathway in GBM cells. Furthermore, we identified that SKI is a target of miR-127-3p, suggesting that miR-127-3p is able to activate the TGF-β signaling pathway via SKI. TGF-β signaling has been found to play pivotal roles in GBM carcinogenesis and progression (Jennings and Pietenpol, 1998; Joseph et al., 2013; Lin et al., 2010a). For example, TGFBR1, which is overexpressed in GBM tissues compared with normal brain tissues (Kjellman et al., 2000), appears to be a potential target for GBM therapy. Zhang et al. (2011) showed that a blockade of TGF-β signaling by the TGFBR1 kinase inhibitor LY2109761 enhances the response to radiation and prolongs survival in glioblastoma patients. Anido et al. (2010) showed that TGF-β receptor inhibitors target the CD44(high)/Id1(high) glioma-initiating cell population in human glioblastoma. Future studies are warranted to further explore the possibilities of using miR-127-3p and SKI as targets for glioma therapy.

Conclusions

Taken together, our data indicate that miR-127-3p was downregulated in GBM tissues compared with normal brain tissues, and that simultaneous DNA demethylation and histone deacetylase inhibition resulted in downregulation of miR-127-3p in GBM cells. In addition, we demonstrated that miR-127-3p inhibits GBM cell growth by inducing G1-phase arrest both in vitro and in vivo. Furthermore, we showed that SKI, RGMA, ZWINT, SERPINB9, and SFRP1 are the direct target genes of miR-127-3p. Finally, we found that miR-127-3p activates TGF-β signaling to suppress GBM cell growth by targeting SKI in GBM.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The work was funded by Grant 81072060 from the National Natural Science Foundation of China; Grants 2008DFA11320 and 2012AA022705 from the Ministry of Science and Technology, China; Grant 20110101120153 from the Ministry of Education, China; Grant 2012R10021 from the Zhejiang Provincial Government, and Grant 2011A11013 from the Shaoxing Major Scientific and Technological Projects. The funding sources had no role in the study design; the collection, analysis or interpretation of the data; the preparation of the manuscript; or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Author Disclosure Statement

The authors declare that no competing financial interests exist.

References

- Anido J, Saez-Borderias A, Gonzalez-Junca A, et al. (2010). TGF-beta receptor inhibitors target the CD44(high)/Id1(high) glioma-initiating cell population in human glioblastoma. Cancer Cell 18, 655–668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bravou V, Antonacopoulou A, Papadaki H, et al. (2009). TGF-beta repressors SnoN and Ski are implicated in human colorectal carcinogenesis. Cell Oncol 31, 41–51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butz H, Racz K, Hunyady L, and Patocs A. (2012). Crosstalk between TGF-beta signaling and the microRNA machinery. Trends Pharmacol Sci 33, 382–393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron EE, Bachman KE, Myohanen S, Herman JG, and Baylin SB. (1999). Synergy of demethylation and histone deacetylase inhibition in the re-expression of genes silenced in cancer. Nat Genet 21, 103–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen D, Xu W, Bales E, Colmenares C, et al. (2003). SKI activates Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in human melanoma. Cancer Res 63, 6626–6634 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deheuninck J, and Luo K. (2009). SKI and SnoN, potent negative regulators of TGF-beta signaling. Cell Res 19, 47–57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon-McIver A, East P, Mein CA, et al. (2008). Distinctive patterns of microRNA expression associated with karyotype in acute myeloid leukaemia. Plos One 3, e2141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filipowicz W, Bhattacharyya SN, and Sonenberg N. (2008). Mechanisms of post-transcriptional regulation by microRNAs: Are the answers in sight? Nat Rev Genet 9, 102–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox JL, Dews M, Minn AJ, and Thomas-Tikhonenko A. (2013). Targeting of TGF beta signature and its essential component CTGF by miR-18 correlates with improved survival in glioblastoma. RNA 19, 177–190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo LH, Li H, Wang F, Yu J, and He JS. (2013). The tumor suppressor roles of miR-433 and miR-127 in gastric cancer. Int J Mol Sci 14, 14171–14184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua D, Mo F, Ding D, et al. (2012). A catalogue of glioblastoma and brain micrornas identified by deep sequencing. OMICS 16, 690–699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennings MT, and Pietenpol JA. (1998). The role of transforming growth factor beta in glioma progression. J Neurooncol 36, 123–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph JV, Balasubramaniyan V, Walenkamp A, and Kruyt FA. (2013). TGF-beta as a therapeutic target in high grade gliomas. Promises and challenges. Biochem Pharmacol 85, 478–485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiyono K, Suzuki HI, Morishita Y, et al. (2009). c-Ski overexpression promotes tumor growth and angiogenesis through inhibition of transforming growth factor-beta signaling in diffuse-type gastric carcinoma. Cancer Sci 100, 1809–1816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JW, Choi CH, Choi JJ, et al. (2008). Altered microRNA expression in cervical carcinomas. Clin Cancer Res 14, 2535–2542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin B, Madan A, Yoon JG, et al. (2010a). Massively parallel signature sequencing and bioinformatics analysis identifies up-regulation of TGFBI and SOX4 in human glioblastoma. Plos One 5, e10210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Q, Chen D, Timchenko NA, and Medrano EE. (2010b). SKI promotes Smad3 linker phosphorylations associated with the tumor-promoting trait of TGFbeta. Cell Cycle 9, 1684–1689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papagiannakopoulos T, Shapiro A, and Kosik KS. (2008). MicroRNA-21 targets a network of key tumor-suppressive pathways in glioblastoma cells. Cancer Res 68, 8164–8172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito Y, Liang G, Egger G, et al. (2006). Specific activation of microRNA-127 with downregulation of the proto-oncogene BCL6 by chromatin-modifying drugs in human cancer cells. Cancer Cell 9, 435–443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahata M, Inoue Y, Tsuda H, et al. (2009). SKI and MEL1 cooperate to inhibit transforming growth factor-beta signal in gastric cancer cells. J Biol Chem 284, 3334–3344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vescovi l, Galli R, and Reynolds BA. (2006). Brain tumour stem cells. Nat Rev Cancer 6, 425–436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P, Chen Z, Meng ZQ, et al. (2009). Dual role of SKI in pancreatic cancer cells: Tumor-promoting versus metastasis-suppressive function. Carcinogenesis 30, 1497–1506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C, Wang C, Chen X, et al. (2010). Expression profile of microRNAs in serum: A fingerprint for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Chem 56, 1871–1879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M, Kleber S, Rohrich M, et al. (2011). Blockade of TGF-beta signaling by the TGFbetaR-Ikinase inhibitor LY2109761 enhances radiation response and prolongs survival in glioblastoma. Cancer Res 71, 7155–7167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.