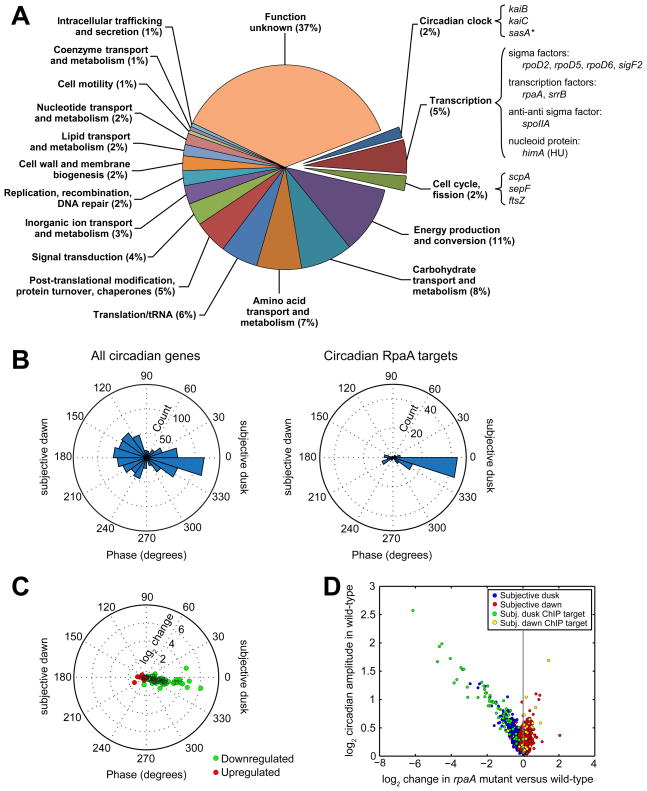

Figure 5. The RpaA regulon.

A. Functional characterization of protein and tRNA ChIP targets of RpaA. We identified 134 transcripts closest to the 110 binding sites (see Extended Experimental Procedures). Of those transcripts, 93 encode proteins or tRNAs (corresponding to 170 genes, some of which are co-expressed in operons), while the other 41 are classified as non-coding RNAs (Vijayan et al., 2011). Because the function of the non-coding RNAs is not known, we restrict our functional analysis to the 170 protein-coding or tRNA genes (“RpaA ChIP target genes”). RpaA ChIP target genes were categorized as described in the Extended Experimental Procedures. Some genes of particular interest are highlighted. The asterisk (*) indicates that the gene’s classification as an RpaA ChIP target is artifactual because of assignment to an incorrectly-demarcated operon containing a bona fide target (Vijayan et al., 2011).

B. Comparison of the distribution of phases of all circadian genes (left, n = 856, from Figure 1A) and of the ChIP target genes whose expression oscillates with circadian periodicity (right, n = 95).

C. Change in expression of circadian ChIP target genes downregulated (green, n = 72) or upregulated (red, n = 23) in the rpaA mutant plotted as a function of their phase in the wild-type strain.

D. Comparison of gene expression change in the rpaA mutant with circadian amplitude in the wild-type strain (from Figure 1B). Only genes that oscillate with circadian periodicity in the wild-type strain are shown (n = 856). Circadianly-expressed RpaA ChIP target genes (n = 95) are highlighted.

See also Tables S1 and S6.