Abstract

Congenital vertebral malformations (CVM) occur in 1 in 1,000 live births and in many cases can cause spinal deformities, such as scoliosis, and result in disability and distress of affected individuals. Many severe forms of the disease, such as spondylocostal dystostosis, are recessive monogenic traits affecting somitogenesis, however the etiologies of the majority of CVM cases remain undetermined. Here we demonstrate that morphological defects of the notochord in zebrafish can generate congenital-type spine defects. We characterize three recessive zebrafish leviathan/col8a1a mutant alleles (m531, vu41, vu105) that disrupt collagen type VIII alpha1a (col8a1a), and cause folding of the embryonic notochord and consequently adult vertebral column malformations. Furthermore, we provide evidence that a transient loss of col8a1a function or inhibition of Lysyl oxidases with drugs during embryogenesis was sufficient to generate vertebral fusions and scoliosis in the adult spine. Using periodic imaging of individual zebrafish, we correlate focal notochord defects of the embryo with vertebral malformations (VM) in the adult. Finally, we show that bends and kinks in the notochord can lead to aberrant apposition of osteoblasts normally confined to well-segmented areas of the developing vertebral bodies. Our results afford a novel mechanism for the formation of VM, independent of defects of somitogenesis, resulting from aberrant bone deposition at regions of misshapen notochord tissue.

Keywords: Notochord, Vertebral Malformations, Collagen, Osteoblast

Introduction

Congenital vertebral malformations (CVM), with an estimated prevalence of 0.5–1 per 1000 persons (Giampietro et al., 2009), presents pathology at birth and display focal vertebral malformations (VM); including, hemivertebrae, wedge-shaped vertebrae, vertebral fusions, and bar vertebrae (Eckalbar et al., 2012). Scoliosis remains a significant health care concern, affecting 2–3% of the population (Weinstein et al., 2008; Wise et al., 2008), with CVM acting as the structural antecedent for the majority of congenital scoliosis (CS) cases (Giampietro et al., 2009). Severe forms of CS, such as spondylocostal dysostosis (SCD) or spondylothoracic dysostosis (STD), are characterized by more contiguous vertebral defects (i.e. encompassing the entire spine) and in some cases are directly attributed to recessive monogenic genes that regulate somitogenesis (Giampietro et al., 2009; Pourquie, 2011). Less severe forms of CS display fewer regions of defective vertebral units and recent data suggests that, in some cases, these defects may be a result of haploinsufficiency of known mutant gene(s) and influenced by an environmental factors, such as hypoxia, during embryogenesis (Sparrow et al., 2012). As such, even minor disruptions in the development of the embryonic axial tissues and/or environmental insults may underlie defective spine development.

The notochord is a defining axial tissue of the chordates, possessing several distinct developmental functions such as patterning information for the ventral neural tube via secretion of Sonic hedgehog (Wilson and Maden, 2005). Structurally, the notochord tissue assists the anterior-posterior extension of the embryonic body during development (Ellis et al., 2013) and provides a flexible, axial rod, crucial for the kinetics of swimming larvae (Adams et al., 1990). The development of the notochord in zebrafish initiates during gastrulation with the tissue-level segregation of internalized chordamesodermal cells along the midline from the bilaterally adjacent presomitic tissues and deposition of Collagen-rich extracellular matrix molecules demarking these notochord-somite boundaries (Glickman et al., 2003; Julich et al., 2009). At the end of gastrulation the individual chordamesoderm cells span the width of the notochord, giving the early notochord its typical “stack of coins” appearance (Glickman et al., 2003; Sepich et al., 2005). The notochord matures via a Notch-dependent morphogenesis where ~70% of notochord cells migrate outward to form a hexagonally arrayed and flat notochord sheath epithelium (Dale and Topczewski, 2011; Yamamoto et al., 2010), while the remaining cells expand their volume via a lysosome-related process of vacuolation driving continued extension of the notochord (Ellis et al., 2013) (see Fig 2A). The notochord is circumferentially wrapped by a tri-laminar extracellular notochord sheath, composed of an inner Laminin-rich basement membrane (Parsons et al., 2002), a middle layer composed of Collagen fibers, and an outer layer composed of Collagen and Elastin fibers lying at orthogonal angles to the middle layer (Grotmol et al., 2006; Scott and Stemple, 2005) (see Fig 2A). The interactions between the inner fluid-filled vacuolated cells (chordacytes) and the extracellular notochord sheath layer generate a mechanically coupled rod-shaped hydrostatic skeleton, which responds to osmotic stresses (Adams et al., 1990; Koehl, 2000). In agreement, the volumetric expansion of the inner vacuolated cells is required for the robust elongation and morphology of the notochord tissue (Ellis et al., 2013) and the inhibition or loss of extracellular matrix components important for the development of the extracellular notochord sheath results in misshapen notochord in the early embryo (Christiansen et al., 2009; Gansner and Gitlin, 2008; Gansner et al., 2008; Gansner et al., 2007; Mendelsohn et al., 2006; Pagnon-Minot et al., 2008; Parsons et al., 2002).

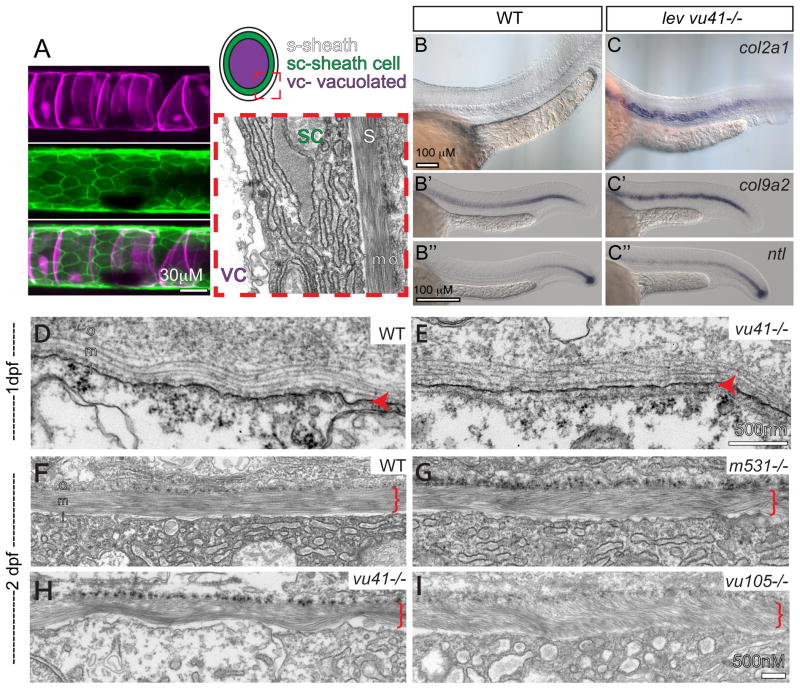

Figure 2. col8a1a mutations disrupt the normal morphology of the notochord sheath.

(A) The primary components of the notochord tissue at embryonic maturation illustrated with a confocal (A, B, C), cartoon (D), and transmission electron micrographs (TEM) (E). The large vacuolated cell layer (VC; Tg(TK5xC twhh:memRFP) expression; magenta), surrounded by a sheath epidermis (SC; 1.75KB col2a1 GFP-CAAX; green) are shown in a lateral view with a confocal projection. The cartoon and the TEM image are transverse views highlighting the extracellular trilaminar notochord sheath (S) composed of laminin-, collagen- and elastin-rich components. (B–C″) Representative examples of in situ hybridization of chordamesodermal genes col2a1 (B, C), col9a2 (B′, C′), and ntl (B″, C″) in WT (B–B″) and levvu41 mutant (C–C″) embryos. (C) The expression of col9a2 and ntl transcripts is upregulated, especially in more anterior regions of the notochord (C′, C″) as compared to time matched sibling embryos (B′, B″). TEM of transverse sections from WT and mutant embryos at 2dpf (D–I). (D) WT notochord at 1 dpf. (E) lev vu41−/− notochord at 1dpf. (F) WT notochord sheath at 2dpf display very straight, well organized medial sheath layer. Extracellular notochord sheaths of lev m531−/− (G), lev vu41−/− (H), and lev vu105−/− (I) mutants exhibiting a wavy, disordered organization of the medial layer at 2dpf. i- inner laminin-rich layer, m-medial, and o- outer collagen-rich layers of the extracellular sheath; SC- sheath cell, S- extra-cellular sheath, and VC- vacuolated cell.

Importantly, the notochord serves as the site of vertebral body condensation during spine development and is the progenitor of the intervertebral tissues, in particular the nucleus pulposus tissues found in mammals (Bruggeman et al., 2012). The patterning information promoting segmented condensation of vertebrae along the axial notochord tissue is thought to derive via the ‘resegmentation’ of the somite blocks. Wherein, a single vertebra is composed and patterned by the anterior and posterior halves of adjacent sclerotome tissue (Verbout, 1976). In agreement, SCD and STD cases are due to disruptions in somitogenesis (Pourquie, 2011), however the majority of cases of human CS are not likely to be explained by disruptions of this process. One outstanding question is whether the classical “re-segmentation” theory can explain the segmentation of the vertebral column (Verbout, 1976). For instance, cell lineage experiments in chicken and in zebrafish suggest a modified mechanism of ‘leaky’ re-segmentation, as labeled sclerotome from one somite can contribute to two adjacent vertebrae (Morin-Kensicki et al., 2002; Stern and Keynes, 1987). This modifies the notion of a strict one-one relationship of somite to vertebral body as posited by the ‘Neugliederung’ model of Remak over a century ago (Morin-Kensicki et al., 2002; Stern and Keynes, 1987; Verbout, 1976).

While the complete mechanism of vertebral column segmentation remains unclear, the notochord and specifically the notochord sheath cells appear to have a role in the initial deposition of centra (chordacentra) in zebrafish and salmon. In teleost fish, the overt segmentation of the vertebral column begins with the formation of rings of bone around the notochord, referred to as centra. In this process, individual centra are deposited outward from the notochord sheath cells – referred to as chordoblasts (Dale and Topczewski, 2011; Grotmol et al., 2003). Moreover, osterix/sp7 expressing, mature osteoblasts are not observed at the notochord during the timing of centra formation in zebrafish or salmon (Bensimon-Brito et al., 2012; Fleming et al., 2004). In addition, focal laser ablation of the zebrafish notochord can completely disrupt the formation of the axial centra in that targeted region (Fleming et al., 2004). Finally, recent evidence suggests that embryonic defects of the notochord tissue are correlated with CVM-like defects of the spinal column in adults (Christiansen et al., 2009; Ellis et al., 2013; Fleming et al., 2004).

Here we extend this evidence by showing that the loss of the col8a1a function, previously associated with kinks and bends of the notochord (Gansner and Gitlin, 2008), is sufficient to generate VM and scoliosis in the adult fish. Moreover, we show that an early, transient loss of the col8a1a function and/or disruption of notochord morphology by drugs inhibiting Lysyl oxidases, is sufficient to generate CS-like spine defects. We utilize periodic imaging of individual zebrafish in order to follow the progression of focal notochord defects towards focal VM during the course of spine development. Ultimately, this work supports the model of notochord dependent vertebral column formation, whereby the patterns of CVM and scoliosis can be consequences of malformations or injury to embryonic notochord tissues.

Results

leviathan (lev) mutant alleles disrupt the zebrafish col8a1a gene

Homozygous zygotic levvu41/vu41, levvu105/vu105 and levpd1100/pd1100 mutant embryos generated from heterozygous aphenotypic parents exhibit severe bends and kinks of the notochord, found in both dorsal-ventral and medial-lateral orientations, as previously described for levm531/m531 mutants (Fig 1A) (Stemple et al., 1996). This notochord phenotype is also observed in embryos reared under conditions of copper deficiency or in the presence of an inhibitor of Lysyl oxidases, β-aminopropionitrile (bAPN) (Gansner et al., 2007), as well as closely phenocopying the early notochord phenotype of a previously characterized col8a1a mutant, gulliver (gulm208) (Gansner and Gitlin, 2008). For all lev alleles (vu41, vu105, m531 and pd1100), dorsal-ventral bending of the notochord is first observed at 1 dpf, beginning at the most anterior region of the notochord and proceeding posteriorly. The severity of the bending after 3dpf is variable, in that sibling homozygous mutant embryos display notochord buckling randomly positioned along the anterior-posterior axis (Supp. Fig 1A). Despite these early notochord defects, embryos homozygous for all the lev alleles can develop into fertile adults; albeit with decreased viability and decreased average standard length (SL) compared with unaffected siblings (Fig 1B and Supp Fig 1B). Maternal zygotic lev mutant embryos, generated by homozygous parents, displayed no enhancement of the embryonic phenotypes and developed into viable, yet shortened adults, as did their zygotic counterparts.

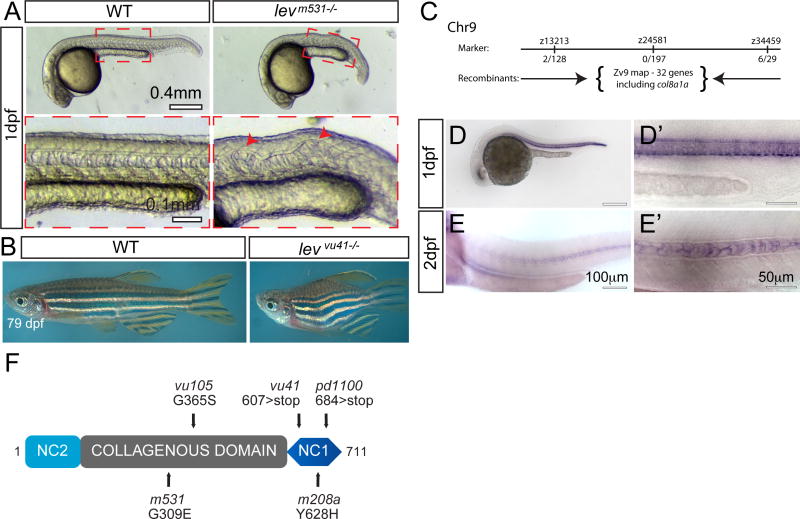

Figure 1. lev zebrafish mutant alleles disrupt the col8a1a gene.

(A) Representative col8a1a (e.g. levm531−/−) mutant embryo displaying kinking of the notochord (red arrowhead) and shortened body axis at 1 dpf. (B) Representative homozygous col8a1a mutant adult (e.g. levvu41−/−) displays shortened body axis. (C) The lev vu41 lesion was meiotically mapped to a region of chromosome 9 between the markers z13213 and z34459 (number of recombinants are noted at each region) and was most highly associated with the SNP, rs40743937 in our bulk segregant analysis. According to the ensemble map (ZV9), 32 genes are located within this critical region flanked by the SSLP markers, including the col8a1a. (D–E′) col8a1a in situ hybridization at 1dpf (D, D′) showing robust expression in several midline structures at 1dpf including the floorplate, chordamesoderm/notochord, and hypochord. At 2dpf (E, E′), the expression is specific to the large vacuolated cells. (F) Structure of the predicted 711-amino acid zebrafish Col8a1a protein. The N-terminal NC2 domain and C-terminal NC1 domain flank the more-canonical collagenous domain. The NC2 domain is thought to be a propeptide domain lost during maturation, whereas the collagenous and NC1 domains are important for trimerization and supermolecular network formation respectively. The G309E (levm531) and G365S (levvu105) substitutions are located with in the collagenous domain (gray box); the 607 nonsense mutation (levvu41) resides just N-terminal to the NC1 domain and the previously described gulm208a mutation.

To determine the molecular genetic basis of the lev phenotype, we first sought to determine an approximate linkage group and chromosomal position for the mutant lesion. We used bulked segregant analysis to identify specific single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) alleles associated with lev mutant pools but not in the mapping strain (Bradley et al., 2011). One SNP --rs40743937;zv9-31629009bp—on chromosome 9 was poorly represented in the mapping strain (WT Allele Frequency 0.003) (Fig 1C). Furthermore, we mapped the levvu41 locus to a defined region of Chromosome 9 using informative Simple Sequence Length Polymorphism (SSLP) markers (Fig 1C) (Knapik et al., 1998). We chose a list of candidate genes in this region to sequence, on the basis of notochord expression from the available zebrafish gene expression database (ZFIN.org). Subsequent sequencing of the candidate genes revealed lesions for all four lev mutant alleles (vu41, vu105, m531 and pd1100) only in col8a1a, the gene also affected in gulm208 mutants (Gansner and Gitlin, 2008). We performed in situ hybridization on wild-type embryos at various stages of development in order to assay the spatiotemporal expression of zebrafish col8a1a during notochord maturation (Fig 1D). In agreement with previous findings (Gansner and Gitlin, 2008) that col8a1a is expressed in the developing chordamesoderm/notochord, floor plate, and the hypochord (Fig 1D, D′). However, we show that col8a1a continues to be expressed in the vacuolated cells of the mature notochord, while other midline structures and the notochord sheath cells down regulate col8a1a expression (2dpf) (Fig 1E, E′).

The levvu41 and levpd1100 alleles are nonsense mutations at aa607 (Tyrosine) and aa684 (Glutamine) respectively, both predicted to truncate the C1q-like NC1 domain of Col8a1a protein (Fig 1F). The levvu105 and levm531 alleles are missense mutations affecting evolutionarily conserved Glycine residues – of the canonical Gly-X-Y motif commonly found in the so-called collagenous domains of many Collagen proteins (G365S and G309E respectively) (Fig 1F) (Ricard-Blum, 2011). ClustalW alignments (Higgins et al., 1996) demonstrated that all mutated Col8a1 protein residues altered by the levvu41, levvu105, levm531 and levpd1100 alleles, are highly conserved in other vertebrate homologues of Col8a1 protein (Supp Fig 2).

Since the gulm208 is a col8a1a allele (Gansner and Gitlin, 2008), we further tested the hypothesis that lev is a col8a1a allele by complementation testing of levvu41 against gulm208 (Table 1). The finding that transheterozygotes for levvu41 and gulm208 have the same phenotype as levvu41/41 homozygotes and similar to gul m208/m208 homozygotes at 1dpf provided further support for the notion that levvu41 is a new allele of the col8a1a locus.

Table 1.

Complementation testing for lev and gul alleles

| Genetic Cross | Notochord defect (%) | Loss of lower mandible (%) | n= |

|---|---|---|---|

| gulm208/+x gul/m208/+ | 11 (20.0) | 13 (23.6) | 55 |

| levvu41/+ x levvu41/+ | 47 (19.5) | 0 (0.0) | 244 |

| gulm208/+ x levvu41/+ | 210 (22.3) | 0 (0.0) | 942 |

| gulm208/+ x levm531/+ | 35 (9.4) | 0 (0.0) | 373 |

| levm531/+ x levm531/+ | 140 (22.4) | 0 (0.0) | 625 |

| levvu41/+ x levpd1100/+ | 82 (26.7) | 0 (0.0) | 307 |

In contrast to severe notochord folds observed in all lev mutants, gulm208/m208 mutants exhibit only mild notochord defects at 1dpf, yet display additional abnormalities including: small eyes, impaired mandible development, heart edema, and larval lethality at 4–5dpf (Stemple et al., 1996). We cloned and sequenced the zebrafish col8a1a cDNA from homozygous gulm208/m208 mutants and confirmed the Y628H missense mutation in the original report by Gansner and others (Gansner and Gitlin, 2008). As such, we sought out to understand why striking phenotypic differences characterize gul and lev col8a1a locus mutant alleles in zebrafish. One possibility is that the Y628H (gulm208) mutation acts as a neomorphic allele of col8a1a, causing phenotypes in tissues that normally do not express this gene, accounting for the weaker notochord defect as well as the additional defects in various tissues (i.e. small eyes, heart edema, and impaired mandible development) and lethality observed in larval stages. Alternatively, pleiotropic developmental defects and embryonic lethality not related to the notochord defect could be due to a second site mutation, closely linked to the Y628H mutation affecting col8a1a gene. To distinguish between these hypotheses, we extended complementation tests to ask if the nonsense levvu41 or the missense levm531 alleles would complement either of the gulm208/m208 phenotypes: (1) the early kinked notochord scored at 1dpf; and (2) the impaired mandible development scored at 5dpf. We observed that transheterozygous embryos from gulm208/+ x levvu41/+ or gulm208/+ x levm531/+ crosses displayed notochord defects at 1dpf, however neither of these complementation crosses produced the other pleiotropic phenotypes manifested by homozygous gulm208/m08 mutants mentioned above (Table 1). We interpret these results to mean that the previously described phenotypes observed in gulm208/m208 mutant embryos are the result of homozygosity in two closely linked mutations. One in the leviathan/col8a1a locus, which we now designate m208a and the second, in a still molecularly uncharacterized gulliver locus, which we now name the m208b mutant allele and which is responsible for the pleiotropic phenotypes described for gulm208 (Stemple et al., 1996).

Together these data provide additional support for the role of col8a1a for the normal stability of notochord tissues and explain the puzzle of mutations in notochord-expressed col8a1a underlying the pleiotropic effects and early lethality observed in gulm208 mutants (Gansner and Gitlin, 2008). Finally, we demonstrate a necessity of col8a1a function for the normal extension of the body axis in embryos and in the adult.

Cell and Tissue Bases of Notochord Defects in leviathan Mutants

Concurrent with the molecular characterization of the lev/col8a1a mutations, we sought to understand the cellular and tissue level defects associated with the notochord dysmorphology they are causing. Our analysis focused on the three major components of the notochord tissue: the vacuolated cells; the sheath epithelium; and the surrounding extracellular notochord sheath (Fig 2A).

Previously described notochord mutants, such as grumpy and sleepy affecting Laminins, were found to have extracellular sheath defects and also to display a persistent expression of chordamesodermal marker genes in the developing notochord (Parsons et al., 2002). Similarly, we observed persistent expression of the chordamesodermal markers col2a1, col9a2, and ntl in levvu41/vu41 mutant embryos at 2dpf (Fig 2C–C″), when expression of these genes was no longer detected (Fig 2B) or diminished in the anterior region of wild-type siblings (Fig 2B′,B″). A predicted, secreted Col8a1 protein, likely provides a necessary extracellular matrix component during development. In order to visualize the Col8a1 protein directly we fluorescently tagged wild-type col8a1a using various strategies to conserve the N-terminal signal peptide, we also to generated a zebrafish specific peptide-based rabbit antibody (ac-PHYRKDLPMHLNKGKDNKC-amide; AA54-72), however both strategies were ineffective in reporting the location of the Col8a1a protein (data not shown). Analyses of the extracellular notochord sheath in lev/col8a1a mutant embryos, revealed no loss of the inner Laminin rich layer using whole mount immunohistochemistry (data not shown). In order to assess any ultra-structural defects in the extracellular sheath, we next analyzed transverse sections for all col8a1a mutants and wild-type siblings at 1dpf and 2dpf with transmission electron microscopy (TEM) (Fig 2D–I). At 1dpf, intercalated chordamesodermal cells undergo a Notch-dependent transition (Yamamoto et al., 2010) to form the inner vacuolated cell core and the outer sheath cell epithelium that is completed by 3dpf (Dale and Topczewski, 2011). As this process begins in the anterior notochord region and progresses posteriorly, we focused our analysis of 1dpf and 2dpf embryos on the more anterior portion of the notochord, just posterior to the yolk sac (~the 5th somite). The electron dense innermost basement layer (Laminin-rich) was present in both mutant and wild-type samples (red arrowhead Fig 2D, E). We observed no qualitative changes in the middle or outer layers of the notochord sheath when comparing lev/col8a1a mutants with wild-type samples at 1dpf. Moreover, the straightness or waviness of the middle layer fibers varied along the circumference of the 1dpf notochord, regardless of genotype (Fig 2D, E).

At 2dpf, the anterior notochord had mostly completed the morphogenesis of the vacuolated cells and the surrounding hexagon-arrayed sheath epithelium (Fig 2A). In addition, at 2dpf, the middle layer of the extracellular sheath is doubled in thickness (i.e. 250nM at 1dpf; 500nM at 2dpf) and exhibits an increased density of well-organized Collagen fibers in comparison to the extracellular middle-layer notochord sheath at 1dpf (red brackets, comparing Fig 2D, F). Moreover, the collagen fibrils of the middle-layer extracellular notochord sheath were very straight along the entire circumference in wild-type embryos (Fig 2F). In contrast, we occasionally observed disorganized and thinned regions in this middle layer in all lev/col8a1a mutants, yet interspersed with regions of normal ultra-structure (Fig 2G–I).

In order to assay any cellular defects underlying the notochord bending phenotype of lev/col8a1a mutants, we carried out confocal imaging of Tg(Tk5xc twhh:mCherry-CAAX) transgenic embryos in which the vacuolated cells express membrane-localized mCherry, and Tg(1.7c2a1a:mGFP) transgenic embryos with the notochord sheath epithelial cells expressing membrane localized GFP (Fig 2A and Supp. Fig 3A) (Dale and Topczewski, 2011; Distel et al., 2009). We obtained confocal datasets of the vacuolated cells at 3dpf at the level of the cloaca/vent and utilized volume rendering of the vacuolated cells in order to produce an accurate description of their shapes and volumes (Bitplane IMARIS). We did not observe any significant differences in the numbers of the vacuolated cells within identical spans of notochord length (wild type= 10.7 (n=3 embryos), levvu105/vu105 = 10.6 (n=3 embryos); mean cell number/379.6mM2). Moreover, there was no significant change in vacuolated cell volumes between wild type (n=15 cells) and lev/col8a1a mutant cells (n=10 cells), despite dramatic cell shape changes (Supp. Fig. 3B). In addition, we observed no overt defects in the formation of the notochord sheath cells, in the ability of notochord sheath cells to migrate out of the chordamesoderm, or to divide and form a hexagonally arrayed epithelial layer, despite severe bends and kinks in regions of the notochord (Supp. Fig. 3C). In conclusion, because the cellular notochord components appeared relatively intact in the lev/col8a1a mutants, this points to the instability of the extracellular notochord sheath as the likely primary cause of the notochord bending, and is possibly due to a reduced or missing secretion of Col8a1a protein by the sheath cells.

Loss of col8a1a Function during Early Development Results in Vertebral Column Defects

In order to investigate the adult pathology of impaired or absent col8a1a function, we raised lev/col8a1a mutants to adulthood and analyzed their skeleton (between 30–60dpf) with Alizarin red staining (not shown) or with X-ray microtomography imaging (microCT) of fixed samples (Fig 3A). The use of microCT imaging generates high-resolution datasets (10mM voxels) allowing for a consistent and accurate description of VM in three dimensions. Spinal columns of wild-type fish displayed characteristic morphology of individual vertebrae, where neural and humeral arches extend from the anterior face of individual vertebral units (Fig 3A, A′). In addition, individual vertebral units of wild-type vertebral columns were well separated by unmineralized intervertebral regions (Fig 3A′ and see also Movie 1). In contrast, lev/col8a1a mutants displayed regional VMs (Fig 3C, C′; red arrowheads) and scoliosis (Fig 3D, D′; yellow arrowheads), in both thoracic and caudal portions of the spine (see also Movie 2). We defined a VM as a region of continuous vertebral tissue along the axis of the spinal column that displayed two or more sets of neural and humeral arches extending outward from a vertebral unit (Fig 3C′; red arrowheads and see also Movie 2). Scoliosis was classified as a lateral deviation of the spine (Fig 3D′; yellow arrowhead), viewed from dorsal, greater than or equal to 10 degrees, in agreement with similar metrics in human scoliosis patients (Weinstein et al., 2008). Many of the observed VM were not associated with scoliosis, yet all regions of scoliosis we observed also displayed dysmorphogenesis of the vertebrae; hemivertebrae or fused vertebrae (data not shown). As well, some lev/col8a1a mutants displayed multiple severe CVM without scoliosis (Fig 3E″ red bracket). For this reason, we ignored scoliosis as a variable in our analysis of lev/col8a1a mutants and focused on the incidence of VM.

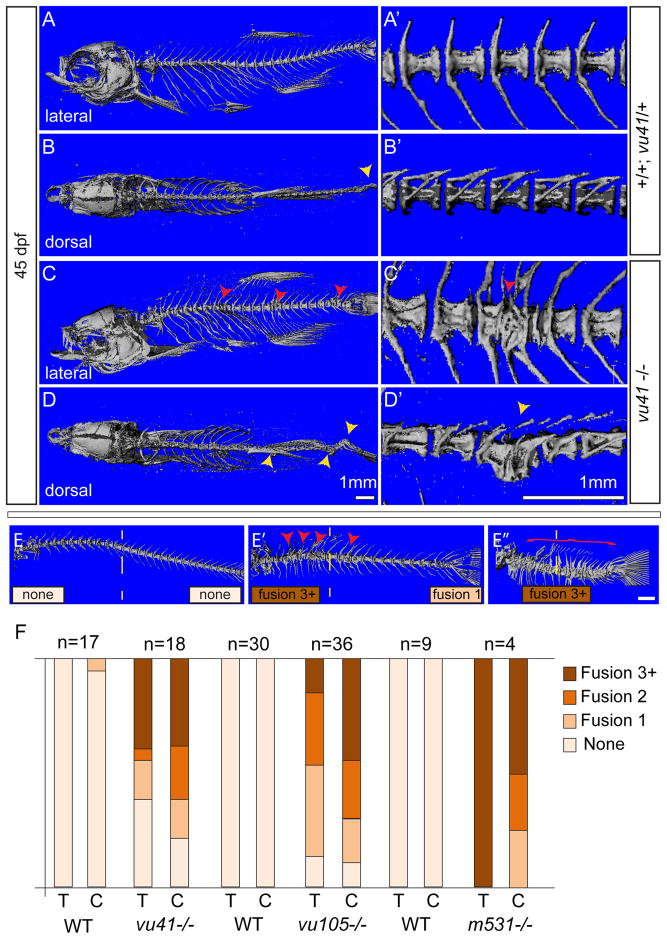

Figure 3. Homozyogus col8a1a mutant adults display vertebral fusions and scoliosis.

MicroCT imaging of WT (A–B′) and col8a1a mutant zebrafish (C–D′) adults (45dpf) (A–E″) in both lateral views (A, C, E–E″) with insets (A′, C′) and dorsal views (B, D) with insets (B′, D′) (A, A′, B′) WT vertebrae with one neural and hemal arches per vertebral body. (B) Representative scoliosis in the tail of a WT adult (yellow arrowhead). (C, C′) Representative levvu41−/− zebrafish with VM (red arrowheads). (D, D′) Representative levvu41−/− multiple scoliosis along the axis (yellow arrowheads) and (E–E″) Representative individuals scored for the presence of individual VM (red arrowheads) or complete fusion of vertebral column (red bracket) in the thoracic or caudal regions (as number of fused regions). (F) Graphed categorical data of VM from all lev alleles and unaffected WT siblings in thoracic (T) and caudal (C) regions. All scale bars (A–D), (A′–D′), and (E–E″) = 1mM.

In order to classify the occurrence of VM in fish homozygous for different lev mutant alleles, we subdivided the occurrences within the thoracic (1st ten or rib vertebrae) and the caudal regions (remaining vertebrae, posterior of last rib) and ranked the incidence of dysmorphogenesis as: None, having no VM (Fig 3E); Fusion 1, presenting with a single VM region (caudal Fig 3E′;red arrowhead); Fusion 2, having two VM regions (not shown); and Fusion 3+ presenting with three or more severely contiguous VM regions (thoracic Fig 3E′ and red bracket Fig 3E″). Using these categorical variables we observed a dramatic increase in the percentage of VM in both thoracic and caudal regions for all lev/col8a1a mutant alleles in direct comparison to age matched unaffected siblings of each allele (not genotyped; predicted to be 33% +/+ and 66% lev /+) (Fig 3F). We observed no significant correlation between the incidence of the thoracic and caudal VM in the mutants, however there was a noticeable increase in the incidence of more contiguous VM (Fusion 3+; Fig 3E) in levm531/m531 mutants (levvu105/vu105 r2= 0.03; levvu41/vu41 r2= 0.48; levm531/m531 N/A).

In order to address the mechanism via which lev/col8a1a mutations generate vertebral column defects, we first assayed the temporal necessity of col8a1a function for normal vertebral column development. The maturation of the notochord is largely complete along the body axis at 5dpf. Subsequent to this is the establishment of the segmented axial centra beginning with the most anterior segments at approximately 5dpf; this is followed by an anteroposterior wave of osteoblast dependent vertebral body formation at approximately 15dpf (Fig 4A). A previously described col8a1a splice blocking antisense morpholino oligonucleotide (MO2-col8a1a; ZFIN.ORG) inhibits normal col8a1a splicing and is thus predicted to generate a frame shift and then a stop codon distal of the first exon (aa178) (Gansner and Gitlin, 2008) (Supp Fig 4B). The injection MO2-col8a1a at both 2ng and 4ng doses into 1-cell stage wild-type embryos phenocopied lev-like notochord defects at 1dpf (Fig 4C), as previously reported (Gansner and Gitlin, 2008). In order to assess the ability of MO2-col8a1a to block splicing of the 1st intron (predicted to be 9,625bp in length; ENSDART00000102981 intron 1), we developed PCR primers flanking this intron. Using standard PCR reaction conditions, these primers should generate an amplicon only after the correct splicing of intron1 of col8a1a. qPCR analysis of cDNA from wild-type uninjected and MO2-col8a1a injected embryos revealed that the range of highest efficacy of the MO2-col8a1a to inhibit col8a1a splicing was between the time of injection at 1 the cell stage and 3 dpf (Fig 4A purple bar and Supp. Fig 4A). Despite the limited ability of MO2-col8a1a to inhibit normal splicing of the col8a1a1 transcript after 3dpf, we consistently observed that MO2-col8a1a injected embryos generated adult fish that were shorter in standard length at 45dpf compared to uninjected controls (Fig 4C′) and displayed increased incidence of VM and scoliosis, in a dose dependent manner, as comparable to observations in homozygous lev/col8a1a mutants (Fig 4C′,E).

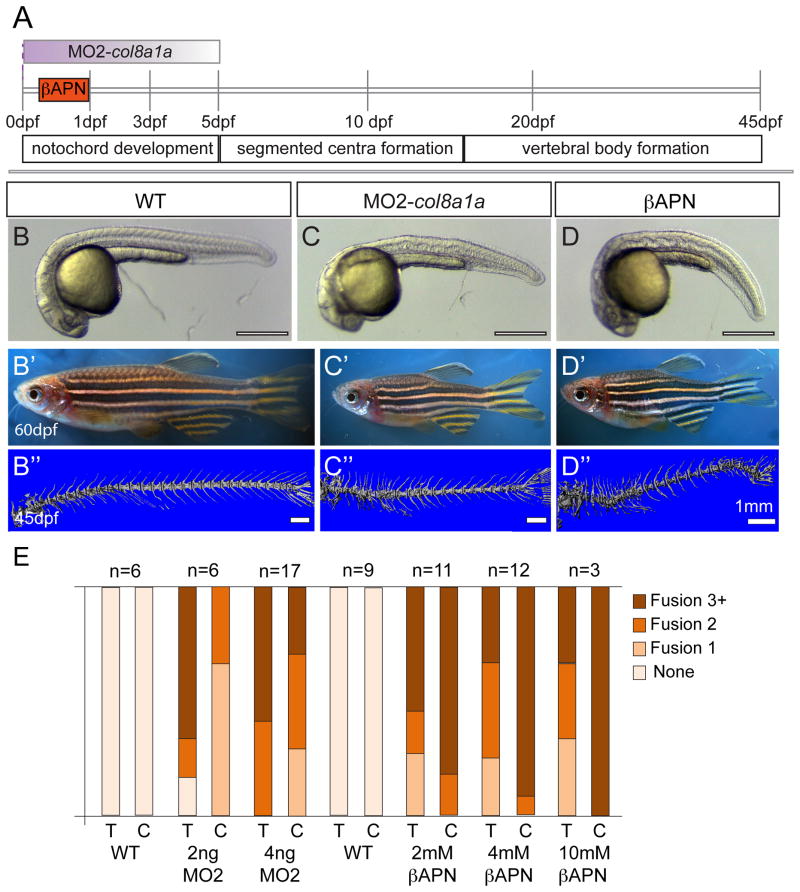

Figure 4. Embryonic inhibition of col8a1a function or lysyl oxidases is sufficient to generate vertebral defects.

(A) Timeline of vertebral column development in zebrafish. In one experiment, the injection of MO2-col8a1a at the 1-cell stage, is effective in blocking the splicing of col8a1a until ~ 3–5dpf (purple gradient bar) (C–C″). In the second experiment the lysyl oxidases inhibitor, bAPN, is added at 4 hpf and washed out at 1dpf (orange bar) (D–D″). Both treatments completed well before the onset of centra formation started in the anterior regions at 5dpf. Representative brightfield images of 1dpf (B, C, D) and 60dpf (B′, C′, D′) and microCT images (45dpf) (B″, C″, D″) of WT (B–B″), MO2-col8a1a injected (C–C″), and bAPN pulsed adult zebrafish (D–D″). (D) Categorical frequency of VM for 2 and 4ng MO2-col8a1a morpholino injected adults and uninjected WT siblings and 2, 4, and 10mM bAPN treated adults and DMSO treated sibling controls for both thoracic (T) and caudal (C) regions. Scale bars for (B, C, D) = 4mm, (B′, C′, D′) = 5mm, and (B″, C″, D″) = 1mm.

As an alternative method to test whether early notochord dysmorphogenesis can lead to adult VM and scoliosis, we employed drug treatments previously shown to interfere with notochord morphogenesis. The notochord defects observed in lev/col8a1a mutants are very reminiscent of phenotypes of embryos reared under conditions of copper deficiency, which indirectly inhibits the function of many cuproenzymes (e.g. Lysyl oxidases). For example, notochord defects are observed in zebrafish embryos injected with MOs targeting genes encoding various Lysyl oxidases (Gansner et al., 2007) or via pharmacological inhibition of Lysyl oxidases by β-aminopropionitrile (bAPN) (Gansner and Gitlin, 2008); and in calamity mutants defective in Atp7a, copper transport ATPase (Madsen and Gitlin, 2008). Because Lysyl oxidases are crucial for the cross linking of fibrillar Collagens and Elastins (Kagan and Li, 2003), we hypothesized that bAPN-specific disruption of the medial and outer layers of the notochord sheath, rich in fibrillar Collagens and Elastins respectively, would be sufficient to generate VM in the adult. Individual clutches of wild-type (AB*) embryos were treated from 4hpf till 24hpf with a range of bAPN (0, 2, 4 and 10 mM) doses (Fig 4A). As previously reported, all bAPN-treated embryos displayed notochord defects (Fig 4D) (Gansner and Gitlin, 2008). Whereas many of the bAPN treated embryo died as larvae in a dose dependent manner, those that survived displayed shorter standard length at 45dpf (Fig D′). Using microCT imaging, we observed VM in these bAPN-treated adult fish, in both thoracic and caudal regions of the spine and in a dose dependent manner (Fig 4D″, E). Therefore, like the MO2-col8a1a injections, the early notochord defects caused by the pulse of bAPN (4hpf-24hpf), resulted in skeletal defects in the adult (45dpf).

The limited perdurance of MO function in the zebrafish larvae (median time of effectiveness ~3.5 dpf) (Mellgren and Johnson, 2004) (and this work), indicates that col8a1a is specifically required during embryonic development for normal vertebral column morphology in the adult. Moreover, both lev/col8a1a mutants and MO2-col8a1a injected adults displayed similar indices of VM and shortened adult body length. Thus, we conclude that Col8a1 function is required for normal vertebral column development at a time prior to the onset of centra formation. Finally, these data together with the results of bAPN treatments support a general requirement of Collagen function during embryogenesis, first in the normal properties of the extracellular notochord sheath, consequently for the establishment of normal notochord morphology, and ultimately promoting normal spine development.

Focal notochord defects can result in focal vertebral fusions and scoliosis

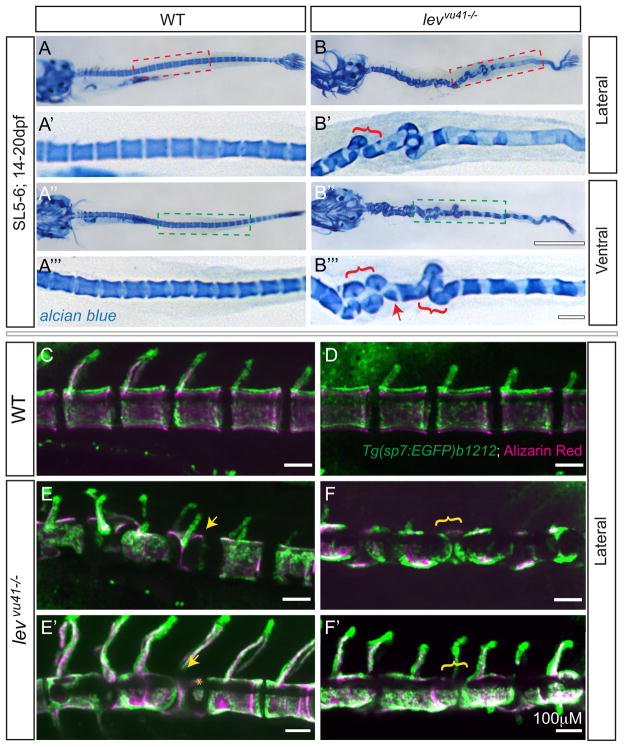

Next we asked which tissues are affected in lev/col8a1a mutants and could contribute to the scoliosis phenotype. Congenital forms of scoliosis in humans are the result of VM (Hedequist and Emans, 2007); some of which are attributed to defects in the somite segmentation (Pourquie, 2011). However, our morphological assessment of col8a1a mutants during segmentation did not reveal any somitogenesis defects (data not shown). We also utilized phalloidin staining of filamentous actin to assess somite segmentation at 1dpf in levvu41/vu41 mutants and unaffected siblings, and observed well-formed, chevron shaped somites (Supp Fig. 5) indicative of normal somite development (Stickney et al., 2000). Moreover, all lev/col8a1a mutants and MO2-col8a1a injected larvae can generate swimming fish, albeit with shorter body lengths and vertebral column defects. For this reason, we hypothesized that the VM observed in lev/col8a1a mutants might arise as a consequence of a spatially disrupted notochord template, which could effect the formation of correctly segmented centra along the notochord axis. To observe segmentation of the centra in whole larvae, we utilized Alcian blue staining in unaffected wild-type larvae of SL5-6 (~14–20dpf) and affected sibling mutants. We observed occasional defects in the normal spacing and morphology of the vertebral centra along the notochord in levvu41/41 mutants (Fig 5B–B‴). In regions of severe notochord bends we noted the formation of hemicentra (Fig 5B‴; red arrow) and the aberrant apposition of centra (Fig 5B‴; red brackets). The fidelity the pattern of centra formation along the notochord was not severely disrupted; following the line of notochord, despite large bends and kinks. Moreover, intervertebral regions normally perpendicular to the midline (Fig 5A′, A‴) were in many cases parallel to the notochord axis (Fig 5B‴, red brackets).

Figure 5. Segmentation of the vertebral column and localization of osteoblasts proceeds on a dysmorphic notochord template.

Alcian blue stained larvae (14dpf) (A–B‴) with lateral insets (red dashed box; A′, B′) and ventral insets (green dashed box; A‴, B‴). (A–A‴) WT larvae display well-formed and segmented centra. (B–B‴) levvu41−/− larvae display abberant apposition of centra (red brackets) and hemicentra (red arrow). Confocal projections of zebrafish vertebral column at 21dpf, illustrating boney matrix (alizarin red in magenta) and osteoblasts (Tg(sp7:EGFP)b1212 in green) (C–F′). (C, D) WT vertebrae and associated osteoblasts are well segmented along the vertebral axis. (E, E′) An individual levvu41−/− mutant displaying segmented colocalization of osteoblast and centra, including malformed hemivertebrae (yellow arrows) that continues to have mostly well segmented osteoblasts (E′), excepting some ectopic osteoblast-mineral formations in regions previously devoid of osteoblasts or mineral (E′, yellow asterix).

(F, F′) An individual levvu41−/− mutant displaying regions of severe notochord bending with aberrantly apposed osteoblasts (F, yellow bracket), those progresses to a region with more complete osteoblast coverage (F′, yellow bracket). (C,D) 10dpf; ~SL3–4 (E,F) 10 dpf; ~SL3–4 (E′, F′) 14dpf; ~SL4–5. Scale bars for (A, B, A″, B″) = 1mM; (C–F′) and (A′, A‴,B′,B‴) = 100mM.

The formation of the mineralized centra does not seem to require sp7/osterix expressing or zns5 antibody-stained osteoblasts in zebrafish (not shown and (Fleming et al., 2004)). However, the formation of the fully elaborated vertebral units with neural and humeral arches requires sclerotome-derived osteoblasts. The Tg(sp7:EGFP) transgenic zebrafish line marks mature osteoblasts (DeLaurier et al., 2010) and, in combination with vital Alizarin Red staining (Kimmel et al., 2010), we first observed osteoblasts at neural arches, followed by the localization of osteoblasts along the area of the mineralized centra and then excluded from sites of non-mineralized developing intervertebral disc (IVD) regions (Fig 5C, D). This raised the possibility that the osteoblasts in lev/col8a1a mutants may display aberrant localization within IVD regions, thus promoting VM. Inconsistent with this model, we observed no defects in the localization of osteoblasts in lev/col8a1a mutants during the early phases of centra development. Osteoblasts were associated with the mineralized centra and excluded from IVDs (100% of levvu41/41 larvae observed at 10dpf; n=6) (Figure 5E, F) and in regions with malformed hemivertebrae (yellow arrow Fig 5E, E′). However, in regions of severe notochord bending, we routinely observed regions of osteoblast apposition (yellow bracket Fig 5F). In some cases, these apposed groups of osteoblasts could progress to condensations of osteoblasts spanning the notochord bends observed previously (yellow bracket Fig 5F′) (33% of levvu41/41 larvae; n=6). The apposition of osteoblasts and spanning across intervertebral regions or the formation of hemivertebrae was not observed in wild-type larvae (0/10).

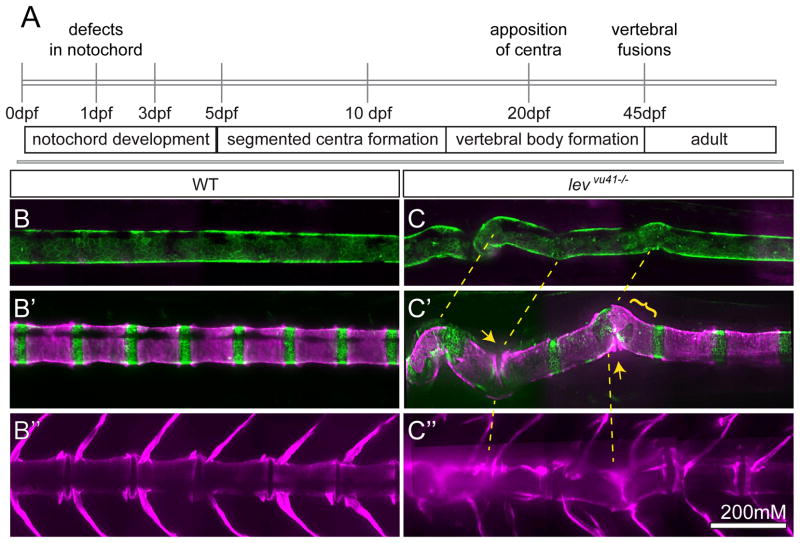

We hypothesized that regional VM and scoliosis observed after 5dpf are consequences of regional notochord defects that arise in the early embryo. To test this, we used the Tg(1.7c2a1a:mGFP) transgenic fish (Dale and Topczewski, 2011) and vital Alizarin red staining (Kimmel et al., 2010) in order to image vertebral column development in individual zebrafish over time (10–40 dpf) (Fig 6A, B–B″). The notochord is the first axial structure of the vertebral column that is established (Fig 6B); followed by the segmentation of the axial centra (Fig 6B′); and finally the elaboration of the vertebral bodies by osteoblasts (Fig 6B″). Zebrafish vertebral column development takes place over many weeks of larval development and requires nutrient intake (Parichy et al., 2009), as such, we were unable to directly visualize this process in real-time. Rather, we analyzed wild type and lev/col8a1a mutant larvae at periodic intervals using these methods. We set out to observe individuals at well-spaced intervals in order to capture informative periods of vertebral column development. A survey of mutant individuals showed that subtle bends in the notochord at 10dpf (Fig 6C), could progress in severity over the course of larval development by 20dpf (yellow dashed lines Fig 6C, C′) (n=4). Moreover, the formation of centra within regions of severe notochord bending displayed morphological changes, including apparent fusions at centra edges and aberrant morphology of centra boundaries (Fig 6C′). In contrast, regions not associated with notochord bending in lev/col8a1a mutants displayed normally spaced centra with well-defined borders (Fig 6C′).

Figure 6. Periodic imaging of individual col8a1a mutants illustrates the progression of notochord bends towards malformed vertebral units.

(A) Timeline of vertebral column development in zebrafish highlighting the timing of this particular periodic imaging method. Confocal projections of an transgenic individuals WT (B–B″) or col8a1a/levvu41−/− mutant (C–C″), and vitally stained with alizarin red (Tg[1.75KB col2a1 GFP-CAAX]; green (B,C′) and Alizarin Red; magenta (B–C″) periodically imaged over the range of vertebral column development. (B, C) mature notochord (10dpf; ~SL 3.5–4) (B′, C′) segmentation of axial centra (20dpf; ~SL 5–6) (B″, C″) mature vertebral column (39dpf; ~SL 8–9). (C) lev mutant individual at 10dpf displaying subtle bends in the notochord which transition to larger bends (yellow dashed lines (B′)). (C′) At 20dpf, these bends can display dysmorphic centra morphology (yellow bracket) or close apposition of centra edges in regions of severe bending (yellow arrows). (C″) At 39 dpf, the formation of VM and scoliosis is predicted from the previous disrupted notochord regions (yellow dashed line). Scale bar is 200mM.

While earlier developmental stages can be easily imaged at high resolution (Fig 6B, B′, C, C′), the formation of mature vertebral bodies coincides with the onset of juvenile development including the formation of epidermal scales and a highly pigmented, keratinized squamous epithelium; contributing to light scattering and an inhibition of light collection. In addition to the onset of adult epithelial features, lev/col8a1a mutants are not planar (due to scoliosis) throughout the depth of focus, making high resolution imaging of some regions of the vertebral columns difficult (Fig 6C″). Despite these challenges we were able to follow, albeit with low resolution, the formation of VM in individual adults from previously bent regions of the embryonic notochord (yellow dashed lines (Fig 6C–C″).

These results illustrate that regional bends of the notochord, caused by loss of lev/col8a1a function, can progress in severity over time and can generate regional malformed centra or the apposition of developing centra. These observations support the notion that these regional bends of the notochord can bring together normally well-separated groups of osteoblast cells. In turn, this aberrant apposition of osteoblasts might facilitate the formation of VM and promote the ossification of some notochord bend and kinks into regions of scoliosis. Taken together, these observations suggest that, in addition to its role in embryonic axis extension and larval motility, the notochord has an important role in the normal development of the spinal column.

Discussion

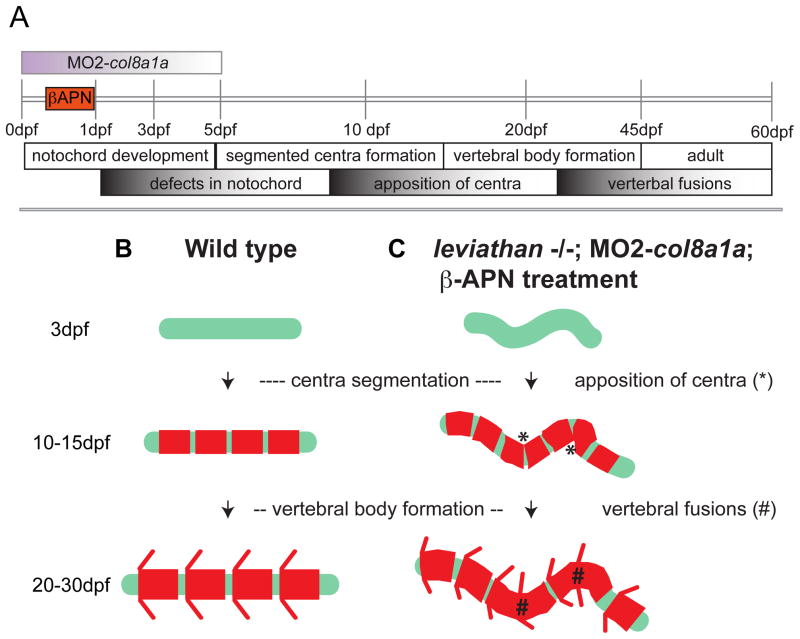

Our genetic analyses of the lev/col8a1a gene extend previous studies in zebrafish to support the notion that VM and scoliosis in adults can be traced back to embryonic notochord defects (Fig 7A, C)(Christiansen et al., 2009; Ellis et al., 2013; Madsen and Gitlin, 2008). We characterized three independent recessive missense and nonsense alleles of lev/col8a1a; all displaying embryonic notochord defects that transition into defects of the vertebral column in the adult. Furthermore, we provide evidence that early and transient loss of lev/col8a1a function (0–3dpf) or transient inhibition of Lysyl oxidases (4hpf–24hpf) is sufficient to generate both early notochord defects and consequently VM and scoliosis in adult fish (Fig 4, and 7A, C). Ultra-structural analysis showed the middle-layer of the extracellular notochord sheath displays disorganization in all lev/col8a1a mutants, without overt defects in the formation of the cellular components of the mature notochord – the vacuolated cells (chordacytes) and the sheath epithelium (chordoblasts). Based on these data we suggest that structurally defective extracellular notochord sheath in lev/col8a1a mutants underlies the formation of embryonic notochord defects, which in turn contribute to the formation of VM and scoliosis in adults. Our work also proposes a novel mechanism for the formation of a shortened adult body axis. We demonstrate that early lev/col8a1a function and the extracellular notochord sheath is necessary for both elongation and straightening of the embryonic and adult body axis. Finally, our studies provide support for the hypothesis that the structural properties and wrapping of the extracellular notochord sheath are necessary for the normal hydrostatic mechanics of the notochord tissue as a whole, as hypothesized by previous ex vivo data (Adams et al., 1990; Koehl, 2000).

Figure 7. The formation of vertebral fusions and scoliosis are consequences of notochord defects.

(A) Timeline of vertebral column development in zebrafish. All manipulations of the notochord in this study are first observed at 1dpf but can progress for some time afterwards in a stochastic fashion (graded bar defects in notochord). The segmentation of the axial centra begin well after the effectiveness of inhibition of lysyl oxidases or col8a1a splicing (orange bar and gradient purple bar), and proceeds prior to and after the observation of centra apposition. Finally, VM are presumed to form continuously from 30dpf onward at regions of centra apposition. (B) Wild type zebrafish form a straight, stiff notochord (green line). This notochord provides a template for the segmentation of the axial centra (red rectangles). These axial centra then provide a template for the elaboration of osteoblast dependent formation of the vertebral bodies. (C) However, when the notochord becomes dysmorphic by early loss of col8a1a function or through the loss of activity of lysyl oxidases, the stereotyped segmentation of the axial centra is disrupted allowing for apposition of centra (*) in regions of severe bending. Finally, as the deposition of vertebral bodies proceeds closely apposed osteoblasts might simply bridge small gaps and generate VM and stabilize regions of bend notochord forming a region of scoliosis (#).

How does the embryonic notochord affect the process of vertebral column development? In teleost fish, the formation of the axial centra (chordacentra) provides a segmented matrix for subsequent development of vertebral bodies (Grotmol et al., 2003). In that, centra are formed by the direct mineralization of the extracellular notochord sheath (Wang et al., 2013) and ultimately the elaboration of the vertebral bodies is carried out by the actions of sclerotome-derived osteoblasts on these segmented templates (Grotmol et al., 2003). We suggest that vertebral defects observed in lev/col8a1a mutants are directly attributed to the function of the notochord as a linear “vertebral body template”. Thus, in regions of severe kinks of the notochord there may be aberrant joining of normally well-separated ossifying regions (centra) that can promote the formation of focal VM and/or stabilize focal kinks in the notochord, consequently leading to regions of scoliosis. Interestingly, we never observed any major loss of the fidelity of the segmented pattern of centra deposition along the notochord; despite severe kinks and bends (Fig 5B–B‴). This could be due to the early deposition of sclerotome derived osteoblast precursors (col10a1 positive cells) that would be patterned prior to the onset of severe notochord defects (2–3dpf), as recently proposed for medaka (Renn et al., 2013). Alternately, this could highlight an intrinsic role of the notochord to provide direct patterning information for establishment of the axial centra. The most likely candidate cellular component controlling notochord dependent segmentation information would be the notochord sheath epithelium. This tissue is intrinsically segmented as revealed by the expression of Tg(1.7c2a1a:mGFP) transgenic zebrafish, in the expression of col2a1a in anti-phase with mineralized centra regions throughout the development of the spinal column (Dale and Topczewski, 2011). We hypothesize that the sheath epithelium turns off col2a1a and begins to secrete factors necessary for localized mineralization of centra. Presumably this could be analogous to mechanisms by which hypertrophic chondrocytes can promote tissue mineralization (Kirsch et al., 1997). It will be interesting to uncover how this intrinsic patterning of col2a1a gene expression in the notochord sheath epithelium is determined.

What is the mechanism leading to abnormal notochord defects in lev/col8a1a mutants? The formation of bends and kinks of the notochord progresses from anterior to posterior throughout embryonic development; this is consistent with the pattern of Notch dependent differentiation of the notochord sheath cells, and interestingly, the presence of functional notochord sheath cells is tightly correlated with the deposition of the extracellular sheath (type II Collagen) at 2dpf (Yamamoto et al., 2010). Thus, it follows that the anterior-posterior wave of notochord sheath cell differentiation is synchronous with the deposition of new components of the extracellular notochord sheath. In agreement, we observed the middle layer of the notochord sheath was approximately doubled in the thickness and displayed an increased of the density of the Collagen fibers at 2dpf in comparison to observations at 1dpf (Fig 2B, F). In contrast to previously reported notochord defects due the pharmacological inhibition of MEK1/2 (U0126) (Hawkins et al., 2008), we did not observe outward herniation of vacuolated cells through the extracellular sheath. Rather, all the vacuolated-cell shape changes were in the direction of the acute angle of the notochord bend (see Supp Fig 3A). In addition, the lack of significant changes in lev/col8a1a mutants in vacuolated cell volumes suggests that vacuole inflation is not largely affected in these mutants (see Supp Fig 3B). We speculate that the defects in the notochord of lev/col8a1a mutants are caused by regional failures of the ‘hydrostatic system’ of the differentiating notochord due to loss of a crucial protein component (Col8a1a) of the extracellular notochord sheath. Accordingly, the coupling of forces generated by the vacuolated cells and encompassed by a structurally weak notochord sheath would create disequilibrium of the ‘hydrostatic system’.

In agreement, recent work has shown that the process of vacuolation drives the elongation of the notochord (Ellis et al., 2013). Moreover, in larvae in which vacuolation was inhibited, the notochord displayed bends and kinks, correlated with scoliosis in adult fish (Ellis et al., 2013). Similar correlations between misshapen notochord and vertebral column defects have been previously reported using MOs directed to the zebrafish Collagen type XXVII genes, col27a1 and b (Christiansen et al., 2009) and with the hypomorphic mutants of calamity/atp7agw71 (calgw71) (Madsen and Gitlin, 2008). The loss-of-function of col27a and b has an obvious parallel with this study, in that both Collagen type VIII and XXVII are likely to represent critical components of the extracellular notochord sheath. The Atp7a protein is a copper transporter localized to intracellular secretory compartments, thus can indirectly affect the function of many secretory cuproenzymes, such as Lysyl oxidases (Mendelsohn et al., 2006). As such, homozygous mutants harboring a strong allele of atp7a (calvu69) are embryonic lethal and display pleiotropic defects including undulations of the notochord (Madsen and Gitlin, 2008). In light of our results, we suggest that proximal etiology of the VM and scoliosis observed in calgw71 mutants is via focal notochord defects.

The adult phenotype we describe for lev/col8a1a mutants most closely resembles a milder CS-like phenotype constituting in most cases ≤3 VM (e.g. fusions or hemivertebrae) with occasional scoliosis in the thoracic or caudal region of the spine (Fig 3E). However, in some cases we observed more contiguous VM, affecting the entire spinal column akin to SCD or STD cases in human patients (Fig 3 D). Previous work has shown that human SCD or STD cases are the result of mutations in genes known to be responsible for somitogenesis (Eckalbar et al., 2012; Giampietro et al., 2009). Since the majority of human CVM cases remain undetermined, it remains possible that the mechanisms we report here underlie the pathology of some human cases. With this in mind, previously reported folded/defective notochord mutants (e.g. crash test dummy, kinks, falowany, and falsity (Odenthal et al., 1996; Stemple et al., 1996)) will be valuable resources to uncover new, potentially informative mutations for testing of human CVM and CS samples.

The loss of environmental copper and the subsequent effects on cuproenzymes, such as Lysyl oxidases, have been shown to generate notochord defects during embryogenesis in the zebrafish (Gansner et al., 2007; Madsen and Gitlin, 2008). In addition, both col8a1a and atp7a genes are important for normal notochord morphology in the zebrafish and are sensitized to loss of environmental copper (Gansner and Gitlin, 2008; Mendelsohn et al., 2006). Moreover, our results illustrate that the transient inhibition of Lysyl oxidases during embryogenesis (4hpf-1dpf) is sufficient to generate both embryonic notochord defects and adult defects of the vertebral column as observed in lev/col8a1 mutants. This suggests possible environmental influences for the etiology of CVM and CS through the inhibition of molecules and signaling pathways necessary for notochord differentiation and morphology, during critical early stages of human gestation.

Materials and Methods

Fish stocks and rearing conditions

Gulliverm208 and leviathanm531 were obtained from frozen sperm stocks from the Boston mutant screen (Stemple et al., 1996). Leviathanvu41 and vu105 were found in subsequent screening efforts at Vanderbilt University. Zebrafish were reared under standard conditions at 28.5°C (M., 1993) and staged as described (Kimmel et al., 1995). The 1.75KB col2a1:GFP-CAAX fish was a gift from Jacek Topczewski (Northwestern University, Feinberg School of Medicine Chicago, Il). The Tg[sp7:EGFP]b1212 fish was a gift from Matthew Goldsmith (Washington University School of Medicine Saint Louis, MO). Synchronous, fertilized embryos were obtained for all experiments, which were carried out in accordance with Washington University’s animal protocol guidelines.

In situ hybridization

Embryos were manually dechorionated at the indicated developmental stages, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde-PBS overnight at 4°C, and dehydrated by methanol series. The probe construct was generated by cloning the 5′ end of zebrafish col8a1 into pCRII (Invitrogen). The primers used for the PCR amplification reaction were: forward primer 5′-GAGTGAGCCCACCAATCCTTG-3′ and reverse primer 5′-CTCCTGGACTTCCAATACCC-3′. DIG-labeled antisense RNA probes were synthesized using a DIG-labeling kit (Roche), and whole-mount in situ hybridization was performed as previously described (Thisse and Thisse, 2008).

RT-PCR and quantitative RT-PCR

RNA was obtained from pooled embryos using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen). All cDNA was prepared with Superscript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) or using iScript cDNA synthesis kit (BioRad). PCR amplification over 35 cycles was subsequently performed using 1 μL of cDNA and GoTaq Flexi DNA polymerase (Promega) in a final volume 25 μL. The annealing temperature was 57°C and the extension time 1 minute. For each leviathan mutant full-length col8a1a coding sequence alleles were amplified using forward primer 5′-GAGTGAGCCCACCAATCCTTG-3′ and reverse primer 5′-CCTTCAAATTCTTACTTATTCTTGC-3′ and subcloned using the CRII-TOPO Dual cloning kit (Invitrogen). Sequencing of the full length col8a1a amplicon was done using the the forward primer above; col8a1a 131–148 fwd 5′-TGGGAAAGGAAATGCCAC-3′; col8a1a 617–637 5′-CTGGACCTAAAGGAGACAGAG-3′; col8a1a 1217–1236 5′-CCAGGACCTATTGGGCTAAC-3′; and col8a1a 1790–1811 5′-TTCACTGCCAAACTGACCGCAC-3′. The primers used for detection of correct splicing of col8a1a intron 1 (blocked by col8a1 splice morpholino) were: foward 5′-GTGTGTGTTTTCGGGGTCTT-3′ and reverse 5′-CAGTTGCACCAAAGCTACCA-3′.

Imaging

All confocal images were taken with Quorum Spinning disc Confocal/ IX81-Olympus inverted microscope and Metamorph Acquisition software. All brightfield images were obtained on a Nikon macroscope. All processing of images was done using Fiji or Adobe Photoshop in order to crop, set Levels or Merge image files. Micro CT imaging was performed with a VivaCt40 machine (ScanCo); wrapped in a lightweight porous foam (packing peanuts); and scanned at 10mm resolution (high) with energy of 45kV and intensity of 177mA. For periodic time-lapse imaging all individual zebrafish were anesthetized in 0.016% Tricane-S (MS-222) and quickly mounted in 2% methyl cellulose in the same general orientation (dorsal to the top; anterior to the left) in order to image the same flank at each time interval; however slight changes in the coronal rotation of individuals at each time point was unavoidable. All scale bars were placed using Adobe Illustrator and the correct pixel length of the given imaging modalities and magnification.

Transmission electron microscopy

Live embryos were terminally anesthetized in 4%Tricane-S (MS-222) and fixed in glutaraldehyde /0.1M sodium cacodylate, were sequentially stained with osmium tetroxide and uranyl acetate; then dehydrated and embedded in Polybed 812. Samples were thin sectioned on a Reichert-Jung Ultracut microtome, post stained in uranyl acetate and lead citrate, viewed on a Jeol (JEM-1400) transmission electron microscope, and images were recorded with an attached high-resolution digital camera.

Pharmacologic treatment

Pharmacologic compounds were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). β-aminopropionitrile (A3134) was prepared as 100 mM in egg water. In all cases, embryos were placed in a diluted compound between 3 and 6 hpf and left in solution overnight and washed out thrice with fresh egg water.

Meiotic mapping

levvu41/+ fish in AB background were crossed to the polymorphic WIK strain and the progeny (AB*/WIK) raised to adulthood. The levvu41 mutation was bulk segregate mapped to Chromosome 9 using a panel of 1,536 SNPs conducted using the commercial Illumina GoldenGate assay (Illumina, San Diego, CA). Data was collected in parallel with that of (Bradley et al., 2007). For fine mapping, 197 mutant embryos from AB*/WIK females crossed to AB*/AB males were collected and assessed for recombination along Chromosome 9 by SSLP analysis. DNA from wild type and heterozygous embryos as well as WIK and AB grandparents was used to ensure polymorphism between AB and WIK.

Cloning and annotation

Full-length col8a1 sequence was amplified from wild-type and mutant cDNA and cloned into pCR-II-TOPO (Invitrogen). cDNA for these reactions was generated with Superscript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) and PCR carried out using LA Taq DNA polymerase and high-fidelity buffer (Takara). The primers used for PCR were: forward primer 5′-GAGTGAGCCCACCAATCCTTG-3′ and reverse primer 5′-CCTTCAAATTCTTACTTATTCTTGC-3′. The full-length zebrafish col8a1 coding sequence is available at Genbank (accession number E U781032). The protein sequence alignment of zebrafish Col8a1 with orthologues from other species was created using MacVector. Antisense morpholino oligonucleotide (MO2-col8a1a) targeting the 1st exon-intron boundary of col8a1a were resuspended in water and injected into 1-cell embryos (Gansner and Gitlin, 2008).

Statistical analyses

Data analyses were performed in GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software) and Excel (Microsoft).

Supplementary Material

(A) Representative levvu105−/− mutants at 3dpf illustrating the stochastic nature of the notochord bending. (B) Graph of the standard length (mm) of WT or levvu41−/− mutant embryos. The bends and kinks in the notochord contribute to the significant decrease in the axial length at 2dpf and onward. Error bars are standard error of the mean.

(A) Clustal W alignment of translated leviathan alleles with Human (Hs_col8a1); Mouse (Mm_col8a1); and both Zebrafish homologues of Col8 proteins (Dr_col8a1a and Dr_col8a1b). All residues are highly conserved in higher vertebrates (red boxes).

(A) Volume rendering of confocal projections of vacuolated cells Tg(TK5xC twhh:memRFP) at 3dpf show dramatic cell shape change of the vacuolated cells of lev vu105 affected mutants as compared to a very regular shapes and ordered arrangement of the vacuolated cells of wildtype siblings. All comparisons were done at the same axial level of the zebrafish vent. (B) A comparison of vacuolated cell volumes between levvu105−/− mutant and sibling individuals show no significant change in the distribution of these values. (C) The formation of the sheath epithelium is largely unaffected despite the dysmorphic notochord tissue.

(A) Histogram representing the level of properly spliced col8a1 transcript (exon1-exon2), normalized to WT using both b-Actin and col8a1a (exon1) expression. The relative level of properly spliced is diminished at 2dpf and 3dpf but begins to recover at 5dpf. (B) Diagram of the targeting of the antisense morpholino oligonucleotide at the exon-intron boundary of col8a1a.

Supplemental Figure 5: Phalloidin staining of 1dpf embryos display normal somite segmentation patterns in both WT or levvu41+/− (A,A′) and levvu41−/− (B,B′) mutant embryos.

Highlights.

The notochord serves as a template for the development of the vertebral column.

Embryonic loss of col8a1a results in congenital vertebral malformations (CVM).

Inhibition of lysyl oxidases during embryogenesis results in CVM.

Spatial disruptions of the notochord promote aberrant osteoblast condensation.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Zebrafish Consortium for excellent care of fish stocks as well as members of the Solnica-Krezel and Johnson’s groups for helpful discussions during the evolution of this work. We are very thankful to Stephen Canter for technical assistance. We are grateful to Drs. Diane Sepich, Margot Kossman-Williams, Jonathan Gitlin, Philip Giampietro and Christina Gurnett for critical commentary on this manuscript. This work is dedicated to Howard Gray and the 06010 for inspiration and good humor. This work was funded by a Children’s Discovery Institute fellowship grant (MD-F-2011-143) and an NRSA-F32 (NIMAS-NIH 1F32AR063001-01) to RSG and a Pilot and Feasibility from the Washington University Musculoskeletal Research Center (NIH P30 AR057235) to LSK.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adams DS, Keller R, Koehl MA. The mechanics of notochord elongation, straightening and stiffening in the embryo of Xenopus laevis. Development. 1990;110:115–30. doi: 10.1242/dev.110.1.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bensimon-Brito A, Cardeira J, Cancela ML, Huysseune A, Witten PE. Distinct patterns of notochord mineralization in zebrafish coincide with the localization of Osteocalcin isoform 1 during early vertebral centra formation. BMC Dev Biol. 2012;12:28. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-12-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley KM, Breyer JP, Melville DB, Broman KW, Knapik EW, Smith JR. An SNP-Based Linkage Map for Zebrafish Reveals Sex Determination Loci. G3 (Bethesda) 2011;1:3–9. doi: 10.1534/g3.111.000190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley KM, Elmore JB, Breyer JP, Yaspan BL, Jessen JR, Knapik EW, Smith JR. A major zebrafish polymorphism resource for genetic mapping. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R55. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-4-r55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruggeman BJ, Maier JA, Mohiuddin YS, Powers R, Lo Y, Guimaraes-Camboa N, Evans SM, Harfe BD. Avian intervertebral disc arises from rostral sclerotome and lacks a nucleus pulposus: implications for evolution of the vertebrate disc. Dev Dyn. 2012;241:675–83. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.23750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christiansen HE, Lang MR, Pace JM, Parichy DM. Critical early roles for col27a1a and col27a1b in zebrafish notochord morphogenesis, vertebral mineralization and post-embryonic axial growth. PLoS One. 2009;4:e8481. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale RM, Topczewski J. Identification of an evolutionarily conserved regulatory element of the zebrafish col2a1a gene. Dev Biol. 2011;357:518–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLaurier A, Eames BF, Blanco-Sanchez B, Peng G, He X, Swartz ME, Ullmann B, Westerfield M, Kimmel CB. Zebrafish sp7:EGFP: a transgenic for studying otic vesicle formation, skeletogenesis, and bone regeneration. Genesis. 2010;48:505–11. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Distel M, Wullimann MF, Koster RW. Optimized Gal4 genetics for permanent gene expression mapping in zebrafish. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:13365–70. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903060106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckalbar WL, Fisher RE, Rawls A, Kusumi K. Scoliosis and segmentation defects of the vertebrae. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Dev Biol. 2012;1:401–23. doi: 10.1002/wdev.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis K, Bagwell J, Bagnat M. Notochord vacuoles are lysosome-related organelles that function in axis and spine morphogenesis. J Cell Biol. 2013;200:667–79. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201212095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming A, Keynes R, Tannahill D. A central role for the notochord in vertebral patterning. Development. 2004;131:873–80. doi: 10.1242/dev.00952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gansner JM, Gitlin JD. Essential role for the alpha 1 chain of type VIII collagen in zebrafish notochord formation. Dev Dyn. 2008;237:3715–26. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gansner JM, Madsen EC, Mecham RP, Gitlin JD. Essential role for fibrillin-2 in zebrafish notochord and vascular morphogenesis. Dev Dyn. 2008;237:2844–61. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gansner JM, Mendelsohn BA, Hultman KA, Johnson SL, Gitlin JD. Essential role of lysyl oxidases in notochord development. Dev Biol. 2007;307:202–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.04.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giampietro PF, Dunwoodie SL, Kusumi K, Pourquie O, Tassy O, Offiah AC, Cornier AS, Alman BA, Blank RD, Raggio CL, Glurich I, Turnpenny PD. Progress in the understanding of the genetic etiology of vertebral segmentation disorders in humans. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1151:38–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2008.03452.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glickman NS, Kimmel CB, Jones MA, Adams RJ. Shaping the zebrafish notochord. Development. 2003;130:873–87. doi: 10.1242/dev.00314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grotmol S, Kryvi H, Keynes R, Krossoy C, Nordvik K, Totland GK. Stepwise enforcement of the notochord and its intersection with the myoseptum: an evolutionary path leading to development of the vertebra? J Anat. 2006;209:339–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2006.00618.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grotmol S, Kryvi H, Nordvik K, Totland GK. Notochord segmentation may lay down the pathway for the development of the vertebral bodies in the Atlantic salmon. Anat Embryol (Berl) 2003;207:263–72. doi: 10.1007/s00429-003-0349-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins TA, Cavodeassi F, Erdelyi F, Szabo G, Lele Z. The small molecule Mek1/2 inhibitor U0126 disrupts the chordamesoderm to notochord transition in zebrafish. BMC Dev Biol. 2008;8:42. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-8-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedequist D, Emans J. Congenital scoliosis: a review and update. J Pediatr Orthop. 2007;27:106–16. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0b013e31802b4993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins DG, Thompson JD, Gibson TJ. Using CLUSTAL for multiple sequence alignments. Methods Enzymol. 1996;266:383–402. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(96)66024-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Julich D, Mould AP, Koper E, Holley SA. Control of extracellular matrix assembly along tissue boundaries via Integrin and Eph/Ephrin signaling. Development. 2009;136:2913–21. doi: 10.1242/dev.038935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagan HM, Li W. Lysyl oxidase: properties, specificity, and biological roles inside and outside of the cell. J Cell Biochem. 2003;88:660–72. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimmel CB, Ballard WW, Kimmel SR, Ullmann B, Schilling TF. Stages of embryonic development of the zebrafish. Dev Dyn. 1995;203:253–310. doi: 10.1002/aja.1002030302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimmel CB, DeLaurier A, Ullmann B, Dowd J, McFadden M. Modes of developmental outgrowth and shaping of a craniofacial bone in zebrafish. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9475. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirsch T, Nah HD, Shapiro IM, Pacifici M. Regulated production of mineralization-competent matrix vesicles in hypertrophic chondrocytes. J Cell Biol. 1997;137:1149–60. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.5.1149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knapik EW, Goodman A, Ekker M, Chevrette M, Delgado J, Neuhauss S, Shimoda N, Driever W, Fishman MC, Jacob HJ. A microsatellite genetic linkage map for zebrafish (Danio rerio) Nat Genet. 1998;18:338–43. doi: 10.1038/ng0498-338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koehl MA, Quillin KJ, Pell CA. Mechanical design of fiber-wound hydraulic skeletons: the stiffening and straightening of embryonic notochords. Am Zool. 2000;40:28–41. [Google Scholar]

- MW The zebrafish book : a guide for the laboratory use of zebrafish (Brachydanio rerio) Eugene, OR 1993 [Google Scholar]

- Madsen EC, Gitlin JD. Zebrafish mutants calamity and catastrophe define critical pathways of gene-nutrient interactions in developmental copper metabolism. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000261. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellgren EM, Johnson SL. A requirement for kit in embryonic zebrafish melanocyte differentiation is revealed by melanoblast delay. Dev Genes Evol. 2004;214:493–502. doi: 10.1007/s00427-004-0428-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendelsohn BA, Yin C, Johnson SL, Wilm TP, Solnica-Krezel L, Gitlin JD. Atp7a determines a hierarchy of copper metabolism essential for notochord development. Cell Metab. 2006;4:155–62. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin-Kensicki EM, Melancon E, Eisen JS. Segmental relationship between somites and vertebral column in zebrafish. Development. 2002;129:3851–60. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.16.3851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odenthal J, Haffter P, Vogelsang E, Brand M, van Eeden FJ, Furutani-Seiki M, Granato M, Hammerschmidt M, Heisenberg CP, Jiang YJ, Kane DA, Kelsh RN, Mullins MC, Warga RM, Allende ML, Weinberg ES, Nusslein-Volhard C. Mutations affecting the formation of the notochord in the zebrafish, Danio rerio. Development. 1996;123:103–15. doi: 10.1242/dev.123.1.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagnon-Minot A, Malbouyres M, Haftek-Terreau Z, Kim HR, Sasaki T, Thisse C, Thisse B, Ingham PW, Ruggiero F, Le Guellec D. Collagen XV, a novel factor in zebrafish notochord differentiation and muscle development. Dev Biol. 2008;316:21–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parichy DM, Elizondo MR, Mills MG, Gordon TN, Engeszer RE. Normal table of postembryonic zebrafish development: staging by externally visible anatomy of the living fish. Dev Dyn. 2009;238:2975–3015. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons MJ, Pollard SM, Saude L, Feldman B, Coutinho P, Hirst EM, Stemple DL. Zebrafish mutants identify an essential role for laminins in notochord formation. Development. 2002;129:3137–46. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.13.3137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pourquie O. Vertebrate segmentation: from cyclic gene networks to scoliosis. Cell. 2011;145:650–63. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renn J, Buttner A, To TT, Chan SJ, Winkler C. A col10a1:nlGFP transgenic line displays putative osteoblast precursors at the medaka notochordal sheath prior to mineralization. Dev Biol. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2013.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricard-Blum S. The collagen family. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2011;3:a004978. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a004978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott A, Stemple DL. Zebrafish notochordal basement membrane: signaling and structure. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2005;65:229–53. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(04)65009-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sepich DS, Calmelet C, Kiskowski M, Solnica-Krezel L. Initiation of convergence and extension movements of lateral mesoderm during zebrafish gastrulation. Dev Dyn. 2005;234:279–92. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparrow DB, Chapman G, Smith AJ, Mattar MZ, Major JA, O’Reilly VC, Saga Y, Zackai EH, Dormans JP, Alman BA, McGregor L, Kageyama R, Kusumi K, Dunwoodie SL. A mechanism for gene-environment interaction in the etiology of congenital scoliosis. Cell. 2012;149:295–306. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stemple DL, Solnica-Krezel L, Zwartkruis F, Neuhauss SC, Schier AF, Malicki J, Stainier DY, Abdelilah S, Rangini Z, Mountcastle-Shah E, Driever W. Mutations affecting development of the notochord in zebrafish. Development. 1996;123:117–28. doi: 10.1242/dev.123.1.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern CD, Keynes RJ. Interactions between somite cells: the formation and maintenance of segment boundaries in the chick embryo. Development. 1987;99:261–72. doi: 10.1242/dev.99.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stickney HL, Barresi MJ, Devoto SH. Somite development in zebrafish. Dev Dyn. 2000;219:287–303. doi: 10.1002/1097-0177(2000)9999:9999<::AID-DVDY1065>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thisse C, Thisse B. High-resolution in situ hybridization to whole-mount zebrafish embryos. Nat Protoc. 2008;3:59–69. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verbout AJ. A critical review of the ‘neugliederung’ concept in relation to the development of the vertebral column. Acta Biotheor. 1976;25:219–58. doi: 10.1007/BF00046818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Kryvi H, Grotmol S, Wargelius A, Krossoy C, Epple M, Neues F, Furmanek T, Totland GK. Mineralization of the vertebral bodies in Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.) is initiated segmentally in the form of hydroxyapatite crystal accretions in the notochord sheath. J Anat. 2013 doi: 10.1111/joa.12067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein SL, Dolan LA, Cheng JC, Danielsson A, Morcuende JA. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Lancet. 2008;371:1527–37. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60658-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson L, Maden M. The mechanisms of dorsoventral patterning in the vertebrate neural tube. Dev Biol. 2005;282:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise CA, Gao X, Shoemaker S, Gordon D, Herring JA. Understanding genetic factors in idiopathic scoliosis, a complex disease of childhood. Curr Genomics. 2008;9:51–9. doi: 10.2174/138920208783884874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto M, Morita R, Mizoguchi T, Matsuo H, Isoda M, Ishitani T, Chitnis AB, Matsumoto K, Crump JG, Hozumi K, Yonemura S, Kawakami K, Itoh M. Mib-Jag1-Notch signalling regulates patterning and structural roles of the notochord by controlling cell-fate decisions. Development. 2010;137:2527–37. doi: 10.1242/dev.051011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(A) Representative levvu105−/− mutants at 3dpf illustrating the stochastic nature of the notochord bending. (B) Graph of the standard length (mm) of WT or levvu41−/− mutant embryos. The bends and kinks in the notochord contribute to the significant decrease in the axial length at 2dpf and onward. Error bars are standard error of the mean.

(A) Clustal W alignment of translated leviathan alleles with Human (Hs_col8a1); Mouse (Mm_col8a1); and both Zebrafish homologues of Col8 proteins (Dr_col8a1a and Dr_col8a1b). All residues are highly conserved in higher vertebrates (red boxes).