Abstract

Objectives

Chest pain is a common and frightening symptom. Once cardiac disease has been excluded, an esophageal source is most likely. Pathophysiologically, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), esophageal dysmotility, esophageal hypersensitivity and anxiety disorders have been implicated. Treatment however remains a challenge. Here, we examined the efficacy and safety of various commonly used modalities for treatment of esophageal (non-cardiac) chest pain (ECP) and provided evidence-based recommendations.

Methods

We reviewed the English literature for drug trials evaluating treatment of ECP in PUBMED, COCHRANE and MEDLINE databases from 1968 to 2012. Standard forms were used to abstract data regarding study design, duration, outcome measures and adverse events and study quality.

Results

Thirty five studies comprising of various treatments were included and grouped under five broad catagories. Patient inclusion criteria were extremely variable and studies were generally small with methodological concerns. There was good evidence to support the use of omeprazole, and fair evidence for lansoprazole, rabeprazole, theophylline, sertraline, trazodone, venlafaxine, imipramine and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). There was poor evidence for nifedipine, diltiazem, paroxetine, biofeedback therapy, ranitidine, nitrates, botulinum toxin, esophageal myotomy and hypnotherapy.

Conclusions

Ideally, treatment of ECP should be aimed at correcting the underlying mechanism(s) and relieving symptoms. PPIs, antidepressants, theophylline and CBT appear to be useful for the treatment of ECP. However, there is urgent and unmet need for effective treatments and for rigorous, randomized controlled trials.

Keywords: Esophageal Chest Pain, Non-cardiac Chest Pain Treatment, Hypersensitivity, GERD, Behavioral Therapy

Introduction

Esophageal chest pain (ECP) is common (1) with global prevalence of 13% (2), and affects up to 30% of patients with chest pain (3). It is also described as non-cardiac chest pain (NCCP), because patients describe recurrent retrosternal chest pain, and a cardiac source has been excluded. Because chest pain may herald life threatening disease, if possible an underlying mechanism should be identified. A lack of positive diagnosis leads to frequent ER visits, increasing disability and loss of productivity and increased health care expenditure (4,5). In a large series of patients with ECP, 42 % had GERD, 7 % of patients had motility disorder, and 37% had esophageal hypersensitivity, and 14% were unexplained (6).

Although the precise cause or origin of ECP is not fully understood, mechanisms have been implicated, including gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD), dysmotility, hypersensitivity, altered cerebral processing of pain, autonomic dysregulation, panic disorder and anxiety (7). Because of its heterogeneous nature, there is significant overlap and uncertainty regarding diagnostic criteria for ECP. The Rome III diagnostic criteria proposed that patients have ECP if they report symptoms for 3 months with symptoms beginning at least 6 months before diagnosis and include: i) midline chest pain or discomfort that is not burning quality, ii) absence of evidence that gastroesophageal reflux is the cause of the symptom and iii) absence of histopathology-based esophageal motility disorders (8). However, chest pain is complex and may occur with or without acid reflux disease. Hence, the Rome III criteria may not encompass the heterogeneous nature of this illness.

The aim of this review is to critically examine the evidence for several proposed treatments for ECP, and to provide perspectives regarding its management.

Methods

Literature search

We conducted a search using PUBMED, MEDLINE and COCHRANE databases from 1968 to April 2012. The search terms were “functional esophageal chest pain”, “non-cardiac chest pain” and “esophageal chest pain” and “treatment” and/or “management” or “drug therapy” or “therapeutics”. Full-text manuscripts and written in English were included. Case reports were excluded. Included studies had at least one clinical end point of improvement for ECP. We mostly included RCTs but case control studies for the treatment of ECP were also included when there was lack of high quality data for a particular treatment modality.

Qualitative assessment of study methodology

The authors independently extracted data and disagreements were resolved by consensus. The methodological quality was assessed by Jadad score (9). The quality scale ranged from 0 to 5 points with a low quality of 2 or less and high quality report of at least 3 (9). Although data from published studies are described in the tables, only randomized studies with a score of ≥3 were considered for treatment recommendations and were based on the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendations (10).

The treatment of ECP is directed towards relieving symptoms and ameliorating the key mechanism(s). Because a mechanistic cause was either not elucidated or described in many clinical trials, for the purposes of this review, we felt that the best approach would be to describe the treatments and to group them under five broad therapeutic categories. Also the literature contains terms such as unexplained chest pain, ECP, NCCP, irritable esophagus and others, for the purposes of this review the terms ECP and/or NCCP have been used, largely based on the original author’s description of their studies.

Treatment of ECP related to gastroesophageal reflux disease

Treatment of ECP related to esophageal spastic motility/dysmotility disorders

Treatment of ECP related to esophageal hypersensitivity

Treatment of ECP using non-pharmacological/behavioral approaches

Treatment of ECP using Surgery

Results

Our database search revealed 182 articles, of which 35 met our inclusion criteria and 17 were excluded for cross-search, 41 for non-English language, 32 for being non-original, 30 for nontreatment related, and 27 because of no outcome measures. .Tables (1a, 2a, 3a, 4a) provide details regarding study methodology and design, outcome measures, patient characteristics, including whether cardiac disease was excluded and presence/absence of GERD, results and safety analysis as well as the quality assessment of these studies.

TABLE 1.

| a PPI treatment of ECP related to GERD | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Referenc e |

Method s Score |

Interventio n |

Study Design |

Study Size (n) |

Mean Age Years |

F/M | Duratio n |

Outcome Measures |

Patient characteristics |

Results | Safety Analysis |

| 14 Fass et al. |

5 | Omeprazole 40 mg a.m. and 20 mg p.m. or Placebo |

Double-blind, placebo controlled crossover |

39 | 60 | 1/38 | 7 days then crossov er for 7 days |

CPF and CPS on a VAS Composite chest pain score severity x frequency/wk |

+ve and −ve EGD and/ or positive pH metry, no manometry, −ve cardiac angiogram or – ve cardiac stress tests |

|

1 diarrhea and 1 abdominal pain |

| 19 Achem et al. |

5 | Omeprazole 20 mg BID or Placebo |

Double-blind, placebo controlled |

36 | 49 | 23/1 1 |

8 weeks | CPF and CPS (0– 10); global chest pain rating (better, same and worse) |

−ve EGD (90%), +ve pH metry (100%), +ve/−ve manometry, −ve coronary angiography, or −ve stress thallium test |

|

Mild symptoms of headaches, abdominal pain, diarrhea, nausea and rash |

| 20 Pandak et al. |

5 | Omeprazole 40 mg BID or Placebo |

Double-blind, placebo controlled crossover |

42 | 48 | 24/1 8 |

14 days then crossov er for 14 days |

CPF and CPS improvement in 2 points from baseline VAS(0–10) and > 50% response |

+ve and −ve EGD and/ or +ve pH metry, −ve stress test |

|

Not performed |

| 21Xia et al | 2 | Lansoprazole 30 mg/day or placebo |

Single blind, placebo controlled |

68 | 58 | 26/42 | 4 weeks | CPF and CPS= severity x frequency/wk |

−ve EGD, +ve and −ve pH metry, no manometry, −ve coronary angiography |

|

Not reported |

| 22Bautista et al. |

4 | Lansoprazole 60 mg am and 30 mg pm or placebo |

Double blind, placebo-controlled crossover |

40 | 54 | 9/31 | 7 days then crossover for 7days |

CPF and CPS VAS Composite chest pain score severity x frequency/wk |

+ve EGD and / or pH metry −ve coronary angiogram or – ve cardiac stress test |

|

Not reported |

| 23Dickman et al. |

4 | Rabeprazole 20 mg/day or placebo |

Double blind, placebo controlled, crossover |

35 | 56 | 12/23 | 7 days | CPF and CPS improvement > 50% |

+ve and −ve EGD, and/ or pH metry, no manometry, −ve coronary angiogram or – ve stress test |

|

Not reported |

| 24Kim et al. |

0 | Rabeprazole 20 mg BID |

Open label trial, First week vs second week |

42 | 54 | 17/25 | 2 weeks | CPF and CPS = >50% improvement Composite score= severity x frequency/wk |

+ve and −ve EGD and/ or +ve pH metry, no manometry, −ve stress test |

|

Not performed |

| b Quality assessment of PPIs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference | Randomization | Blinding | Statement on Withdrawals | Total Score |

| Fass et al. (14) | 2 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| Achem et al. (19) | 2 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| Pandak et.al. (20) | 2 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| Xia et al. (21) | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Bautista et al. (22) | 2 | 2 | 0 | 4 |

| Dickman et al. (23) | 2 | 2 | 0 | 4 |

| Kim et al. (24) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

CPF: Chest Pain Frequency CPS: Chest Pain Score (severity) VAS: Visual Analog Scale GERD: Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease

NS: Not Significant

TABLE 2.

| a Trials of ECP related to esophageal spastic motility/dysmotility disorders | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Refere nce |

Meth od Scor e |

Interventio n |

Study Design |

Study Size (n) |

Mean Age |

F/M | Duration | Outcome Measure |

Patient characteristics |

Results | Safety Analysis |

| 30 Richter et al. |

4 | Nifedipine 10–30mg tid vs placebo |

Double blind crossove r study |

20 | 50 | 8/12 | 14 weeks | Peristaltic amplitude, CPF and CPS and Chest Pain Index= Frequenc y x Severity |

ECP and nutcracker esophagus + (manometry) −ve EGD or upper GI x-ray, Bernstein test (14 −ve, 6+ve),−ve or non-obstructing coronary angiography or −ve stress test. |

|

Nifedipine > placebo: facial flushing, edema, headaches, lightheadedne ss, nervousness |

| 31 Nasrall ah et al. |

2 | Nifedipine 10mg tid vs placebo |

Double blind crossove r study |

16 | 29–76 | - | 4 weeks | Global improvem ent in chest pain (0–10 scale) |

ECP+ Achalasia, or nutcracker or spasm, hypertensive LES (manometry), −ve EGD, no pH metry, −ve cardiac catheterization or −ve stress test . |

|

Light headedness= 1 Throbbing headache=1 No change in blood pressure |

| 32 Davies et al. |

4 | Nifedipine vs placebo |

Double blind placebo controlle d |

8 | - | - | 6 weeks | Chest pain using dairy |

ECP+, dysphagia + Esophageal spasm (manometry), + EGD (2), no pH metry, −ve coronary angiography (7) |

|

- |

| 33 Richter et al. |

0 | Diltiazem 90mg qid |

Open label study |

10 | 8 weeks | Chest pain |

ECP+ Nutcracker esophagus (manometry), −ve EGD, −ve Bernstein test, −ve coronary angiography (3/10 pts), others not mentioned. |

|

Minimal side effects |

||

| 34 Drenth et |

3 | Diltiazem 16mg tid |

Double blind crossove r |

8 | 10 weeks | CPF and CPS (intensity) |

ECP+ Diffuse Esophageal Spasm (manometry), −ve EGD, no pH metry, −ve cardiac tests (no details). |

|

No side effects |

||

| 35 Cattau et al. |

3 | Diltiazem 60– 90mg.qid |

Double blind crossove r |

22 | 8 weeks | ECP+ Nutcracker esophagus (manometry), no EGD, no pH metry, −ve cardiac stress test and/or cardiac catheterization |

|

Withdrawal=8/ 22 (34%) |

|||

| 36 Swamy et al. |

0 | Short acting NTG=12 Long acting Nitrate =5/12 |

Open label |

12 | Short acting=<6 months Long acting=6 months to 4 years |

Chest pain |

ECP+ esophageal spasm (manometry), +ve /−ve pH metry correlated to EGD, no cardiac tests. |

|

-Side effects + in GERD group |

||

| 37 Miller et al. |

0 | Botulinum toxin 100 IU injected |

Open-label prospect ive |

29 | 61 | 24/5 | 1–18 months |

CPS (0–4 Likert scale) < 50% in pain severity |

ECP in non-achalasia, non-reflux motility disorders (manometry), −ve PPI test or −ve pH metry,−ve manometry, −ve stress test or – ve cardiac catheterization. |

|

Not reported |

| 38 Storr et al. |

1 | Botulinum toxin 100 IU injected at multiple sites 1–1.5cm levels |

Open-label prospect ive |

9 | 71 | 3/6 | 6 months | Total symptoms score, regurgitati on score, dysphagia score and NCCP score |

ECP and Distal Esophageal spasm (barium radiogram or manometry), −ve EGD, −ve pH metry or PPI test, −ve stress test, or −ve cardiac angiography. |

|

Slight chest pain (transient) < 2 hr after procedure |

| 39 Borjess on et al. |

4 | Lansopraz ole 30mg.bid vs placebo 8 weeks |

Double blind crossove r |

19 | 58 | 9/10 | 8 weeks | CPF and CPS Esophage al manometr y |

Nutcracker esophagus (manometry) 12/19 had GER (pH<4= >4% of time)( pH metry), −ve cardiac tests (no details). |

|

Not reported |

| 40 Eherer et al |

0 | Patients: Sidenafil 50mg, Healthy subjects: Sildenafil 50 mg vs placebo |

Open label study (patients ). (Double blind RCT; healthy subjects only) |

11 patients 6 healthy subject s |

26–30 in healthy subject s |

7/4 patients, 0/6 healthy |

Treatment upto 4 months in patients, healthy subjects received once. |

Esophage al manometr y (vector volume of LOS, pressure amplitude s of esophage al body |

3 Achalasia, 2 Hypertensive LOS, 4 nutcracker oesophagus, 2 oesophageal spasm: (manometry) – ve PPI test. -no cardiac tests |

|

2 had sleep disturbances, or feeling of tightness to the chest, 3 had dizziness and headache. |

| b Quality assessment of studies of spastic motility/dysmotility disorders | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference | Randomization | Blinding | Statement on Withdrawals | Total Score |

| Richter et al. (30) | 2 | 2 | 0 | 4 |

| Nasrallah et al. (31) | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Davies et al. (32) | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| Richter et al. (33) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Drenth et al. (34) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| Cattau et al. (35) | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| Swamy et al. (36) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Miller et al. (37) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Storr et al. (38) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Borjesson et al. (39) | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 |

| Eherer et al. (40) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

GERD: Gastroesophageal Reflux, CPF: Chest Pain Frequency, CPS: Chest Pain (Severity) Score

TABLE 3.

| a Trials of ECP related to visceral hypersensitivity | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Referen ce |

Method Score |

Intervention | Study Design |

Study Size (n) |

Mean Age |

F/M | Duration | Outcome Measure |

Patients characteristics |

Results | Safety Analysis |

| 49 Cannon et al. |

4 | Clonidine 0.1 mg BID or Imipramine 50 mg QHS or Placebo BID |

Double-blind, placebo controlled crossover |

60 | 50 | 40/20 | 10 weeks | CPF and CPI Change in frequency (number of episodes) and intensity from baseline |

ECP+, [Manometry (54, 90% tested); 22 (41%) had motility disorder], no pH metry, +ve Bernstein test (41%), −ve coronary angiogram, and −ve stress test |

|

Imipramine: prolonged QT interval |

| 50 Clous e et al. |

3 | Trazadone 100– 150 mg QD or Placebo QD |

Double-blind, placebo controlled |

29 | 48 | 21/8 | 6weeks |

Global i mprovement in Chest Pain, r esidual distress, manometric changes |

ECP+, Dysmotility (DES, Nutcracker, IEM)(manometry ) −ve esophagogram, no pH test −ve stress test, or – ve cardiac catheterization |

|

Sedation |

| 51 Varia et al. |

4 | Sertraline 50 mg QD or Placebo |

Double-blind placebo controlled |

, 30 | 8 wks | VAS, CPS, BDI, SF36 Change in VAS (baseline-end Rx) |

ECP+, GERD not ruled out (no pH test), no manometry −ve angiogram and/or −ve stress test |

|

Sertraline: nausea, restlessness, decreased libido, delayed ejaculation (all mild) |

||

| 52 Keefe et al. |

5 | CST + sertraline, CST + placebo, Sertraline alone or placebo alone |

Double-blind, placebo controlled |

115 | 48 | 77/3 8 |

34 weeks |

CPS on a VAS (0– 100. BDI, Rate of Change in outcomes |

ECP+ GERD not ruled out (no pH test), no manometry, −ve stress test or −ve coronary angiogram |

|

Dry mouth Diarrhea Sexual side effects Nausea, Headache |

| 53Lee et al. |

5 | Venlafaxine 75 mg or placebo |

Double-blind, placebo controlled crossover |

43 | 24 | 6/37 | 4 weeks | CPF and CPS Composite score (Frequency x severity) > 50% improvement |

ECP+ −ve EGD, −ve pH metry, −ve manometry, 4-weeks off-PPI, −ve cardiac stress test −ve coronary angiogram. |

|

Sleep disturbance, loss of appetite ( 1 withdrew) Prevalence of any adverse events: 52% venlafaxine vs 12% placebo |

| 54 Dorais wamy et al. |

5 | Paroxetine 10– 50mg daily vs placebo |

Double-blind placebo controlled |

50 | 53 | 42/8 | 8 weeks | Physcian Rated Clinical Global Impression Scale + Patient Rated Score |

Cardiac testing: NA |

|

Fatigue and dizziness |

| 55 Spinh oven et al. |

5 | Paroxetine 10– 50mg. daily vs placebo |

Randomize d Double-blind, placebo controlled |

95 | 55 | 48/4 7 | 16 week | NCCP and HADS |

ECP+, no pH metry, no manometry, no EGD, −ve coronary angiography, or −ve stress test, or −ve cardiac history |

|

Similar number of adverse events between paroxetine and placebo n=22 |

| 56 Praka sh et al |

1 | Amitriptyline, Imipramine, Nortriptyline, Desipramine (20–75 mg/day) |

Open-label retrospective review |

21 | 50 | 14/7 | 0.8–8.6 (mean 2.7) years |

Likert Scale (0= no mprove, 3 clinical remission) responders ≥ 2 after treatment and 3 for remission Chest pain Index Freq x severity CPF,CPI |

ECP +, Use of tricyclic antidepressants and 6 month follow-up, −ve EGD, −ve pH metry, −ve PPI response, no cardiac tests |

|

Sedation, anticholi-nergic symptom |

| 57 Raoet al. |

1 | Theophylline 150–250mg. bid |

Open-label |

12 | 46 | 10/2 | 12 weeks |

(VAS) Global chest pain improvemen t =>50% improvemen t |

ECP+, −ve EGD, −ve pH metry, −ve manometry,+ve EBDT, −ve coronary angiography, or −ve stress thallium study. |

|

2 side effects Nausea palpitation, tremor |

| 58 Rao et al. |

5 | Theophylline SR 200 mg bid or placebo |

Double-blind, placebo controlled |

25 | 46 | 18/7 | 8 weeks |

CPF, CPI Change in number of days with chest pain Global assessment (better, same, worse) |

ECP+, −ve EGD, −ve pH metry, −ve anometry,+v e EBDT,-stress test, or −ve coronary angiography. |

|

Theophylli ne: nausea, insomnia, tremor, and lightheaded ness; Placebo: palpitations, insomnia |

| b Quality assessment of trials on visceral hypersensitivity for ECP | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference | Randomization | Blinding | Statement on Withdrawals | Total Score |

| Cannon et al. (49) | 2 | 2 | 0 | 4 |

| Clouse et al. (50) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| Varia et al. (51) | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 |

| Keefe et al. (52) | 2 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| Lee et al. (53) | 2 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| Spinhov et al. (55) | 2 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| Prakash et al. (56) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Rao et al. (57) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Rao et al. (58) | 2 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| Doraiswamy et al. (54) | 2 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

CPF=Chest Pain Frequency, CPI=Chest Pain Intensity, DES=Diffuse Esophageal Spasm, IEM=Ineffective Esophageal Motility, CST=Coping Skills Treatment, BDI=Beck Depression Inventory, SF36=Quality of Life Measure, EBDT: Esophageal Baloon Distention Test, SR: Slow Release, NS: Not Significant

TABLE 4.

| a Trials of behavioral therapy for ECP | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference | Method s Score |

Intervention | Study Design |

Study Size (n) |

Mea n Age |

F/M | Duratio n |

Outcome Measure | Patient characteristics | Results | Safety Analys is |

| 61 Jones et al. |

3 | Hypnotherapy (12 sessions) or supportive therapy & placebo |

Single blind, randomize d controlled |

28 | 57 | 18/10 | 12 weeks |

Global assessment of chest pain 7 point Likert Scale Completely better or c moderately better = improvement |

ECP+ −ve pH metry, −ve EGD, no manometry, −ve coronary angiogram |

|

None |

| 62 Klimes et al. |

2 | CBT vs assessment control |

Single blind, controlled trial |

35 | 41 | 15/2 0 |

12 weeks |

BDI, Frequency chest pain and STAI > 50% imrpovement |

-ECP+ (symptoms persistent 3 months after −ve cardiac evaluation), no pH test, no manometry, −ve stress test, |

|

None |

| 63 Mayou et al. |

3 | CBT vs standard clinical advice |

Single blind controlled trial |

37 | 49 | 22/1 5 |

12 weeks |

CPF and CPS, improve in mood, mental state |

ECP+, no pH metry or manometry, −ve coronary angiography or −ve outpatient cardiac evaluation (no details) |

|

33% drop-out rate |

| 64 Van Peski et al. |

2 | CBT vs usual care | Single blind controlled trial |

65 | 49 | 36/2 9 |

12 weeks |

CPF and duration. Hospital Anxiety - Depression scale (HADS) |

ECP +, no pHmetry or manometry, GI source excluded (no details) −ve coronary angiograpy, or −ve exercise testing, or −ve cardiac history. |

|

None |

| 65 Jonsbu et al. |

3 | CBT or normal care by a general practitioner |

Single blind controlled trial |

40 | 52 | 26/1 4 |

3 sessions (every week) |

Reduction of fear to bodi sensations. CPF using a 1 (daily) to 4 scale (no symptoms in last 6 months), BDI, SF-36 (QOL) |

ECP+ (persistent symptoms after 6 months of −ve cardiac evaluation, no details), no pH metry and manometry |

|

none |

| 66 Potts et al. |

1 | Psychological treatment | Open label trial |

60 | 53 | 38/2 2 |

8 weeks | HADS, CPF and severity Scale: Improvement, same, worse. |

ECP+ (symptoms ≥2/wk after −ve coronary angiography or <50% stenosed coronary arteries), no pH test, no manometry |

|

none |

| 67 Shapiro et al. |

1 | Biofeedback for non-GERD FCP vs standard care |

Open label study |

22, FCP=9, Biofeedback =6, Standard Care=3 Functional Heartburn=1 3 Biofeedback =6 Standard Care=7 |

44 | 3/6 | 10 weeks |

HADS, and Global assessment scale: Free of symptoms (five points), to no change/worse (one point). Improvement = 3 to 5 points |

Functional Heartburn and FCP, −ve EGD, −ve pH metry, −ve coronary angiogram/stress-ECHO test |

|

none |

| 68 Gasiorowska et al. |

3 | Johrei Treatment | Single Blind Controled Trial |

39, Johrei=21 Wait List Control=18 |

54.5 | 13/2 6 |

6 weeks | Daily Symptoms Assessment Diary (Symptom Intensity Score), SF-36, HADS, PSS, SCL-90R |

ECP+, −ve EGD, −ve pH metry, −ve manometry, −ve cardiac angiogram, or −ve stress test |

|

No side effects |

| b Quality assessment of trials of behavioral therapy for ECP | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference | Randomization | Blinding | Statement on Withdrawals | Total Score |

| Jones et al. (61) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| Klimes et al. (62) | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Mayou et al. (63) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| Van Peski et al. (64) | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Jonsbu et al. (65) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| Potts et al. (66) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Shapiro et al. (67) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Gasiorowska et al. (68) | 2 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

FCP=Functional Chest Pain; HADS=Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; STAI=State trait Anxiety Inventory, SCL-90R=Symptom Checklist 90 Revised, PSS: Perceived Stress Scale

Treatment of ECP related to gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)

Pathophysiology

ECP is often presumed to be due to GERD Through activation of esophageal chemoreceptors (11). Demeester showed that 46% of patients with chest pain had acid reflux during ambulatory pH studies (12). pH testing also yielded a combined positive symptom index and/or pathological acid reflux in 50% of individuals (13). Others have shown that acid reflux may cause ECP in 30–60% of patients (6,14). Non-acid reflux may also cause chest pain (15). In one; study on and off PPI therapy .heartburn decreased significantly, but not regurgitation or chest pain indicating that non-acid reflux caused ECP (16). Thus, both acid and non-acid reflux may be involved in the pathogenesis of ECP.

Treatment

Several PPIs have been tried including omeprazole, lansoprazole, rabeprazole. However, the literature on GERD and ECP is inconsistent. In one study, ECP patients with acid reflux were more likely to respond to PPI’s than those without reflux (14). Because non-erosive reflux (NER) represents 70% of the GER population, and approximately 50% of these individuals may experience heartburn without acid reflux (7), not all patients with ECP have abnormal acid reflux. At least one third of patients have physiologically normal levels of acid reflux, and these individuals either have altered afferent receptor dysfunction or aberrant central modulation of pain.

Undoubtedly, acid reflux causes ECP, but is only one of many components of a complex, multifactorial disorder. A recent systematic review, that included 7 RCT (tables 1a &1b) found a therapeutic gain compared to placebo ranging from 56–85% and RR of >50%, 4.3 (95% CI 2.8– 6.7), p<0.001, in GERD positive patients and only 0–17% and RR of 0.4 (95% CI 0.3 to 0.7; p<0.0004) in GERD negative patients. (17). In another meta-analysis of 8 studies, pooled sensitivity, specificity and diagnostic odds ratio for the PPI test versus 24hr pH study and endoscopy were 80%, 74% and 13.8% (95% CI 5.48–34.91) respectively. The pooled risk ratio for continued chest pain was 0.54 (95% CI 0.41–0.71) (17). These data suggest that patients with acid reflux and ECP may improve with PPI, although numbers were small and there was publication bias (17,18).

Omeprazole

Three studies showed that omeprazole was effective in treatment of ECP (14,19,20).

Fass, et al (14), reported 65% improvement in ECP in 39 patients after one 1-week course of omeprazole 60 mg/day, but maximal benefit was noted in GERD positive patients (52% vs. 7%). They suggested that a 7-day PPI trial may serve as a diagnostic and cost-effective approach for GERD-related chest pain (14,20). The “omeprazole test” has a sensitivity of 87%, specificity of 85.7% and positive-predictive value of 90.9%. In summary, there is good evidence (Level I) for omeprazole in GERD-related chest pain, especially in those with esophagitis and/or abnormal 24 hr pH-metry.

Omeprazole – three double blind placebo-controlled trials (14,19,20) with quality scores of 5,5,5. Evidence good, (Level I).

Lansoprazole

In a single blinded study, 92% with GERD and 33% without GERD improved (odds ratio = 22, p<0.001). In the placebo group, there was no difference in response rates between GERD groups (21). The “lansoprazole test” had a sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value and accuracy of 92%, 67%, 58%, 94% and 75% respectively, for detection of GERD-related chest pain. In another randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled cross over study of lansoprazole 60 mg am and 30 mg pm for 7 days, 78% were responders (50% improvement in chest pain score), with lansoprazole and 22% with placebo (p< 0.0143) in GERD positive patients and only 9% in GERD negative patients (30).

Lansoprazole – one double blind and one single blind controlled trial (21,22) with quality scores of 2,4. Evidence fair, (Level II).

Rabeprazole

In a double blind placebo-controlled crossover study of 35 patients, rabeprazole (40 mg) for 7 days showed a response rate of 75% with rabeprazole in GERD positive and 19% in GERDnegative (23). Importantly, majority of GERD-related responders (75%) had erosive esophagitis. Rabeprazole was mostly useful in GERD-related ECP. Rabeprazole - one double blind placebo-controlled trial (23) and open label trial (24) with quality scores of 4,0. Evidence fair, (Level II).

Ranitidine

The efficacy of ranitidine 150 mg QID was evaluated in one open label trial of 13 patients (25), without cardiologic evaluation. All improved but results were better in patients with positive symptom index (SI) on pH metry. Ranitidine- one open label trial with quality score of 1. Evidence poor, (Level III).

Treatment of ECP related to esophageal spastic motility/dysmotility disorders

Pathophysiology

Several motility disorders, have been implicated in the pathogenesis of ECP including diffuse esophageal spasm (DES), “nutcracker esophagus”, achalasia, scleroderma, and nonspecific motility disorders (6,26), however, the evidence is conflicting. In one study, although 32% of patients had dysmotility, none experienced pain during the abnormal manometry (13). Another study of 10 patients with 24-hr endoluminal ultrasonography described sustained esophageal contractions (SEC) during episodes of spontaneous chest pain (27). However, this activity mediated by longitudinal muscle contractions occurred only in a subset and only during some of the pain episodes, and is probably due to heartburn and acid reflux (28). Esophageal spasm may cause ECP and may occur either spontaneously or secondary to noxious stimuli such as acid reflux (29), and this formed the basis for testing with calcium channel blockers (CCB) or nitrates or botulinum toxin injection.

Treatment

Therapeutic trials for this category are summarized in tables 2a & 2b.

Nifedipine

Nifedipine, a calcium channel blocker (CCB) was tested in 3 RCTs (30–32). Twenty patients with ECP and nutcracker esophagus were randomized to receive nifedipine or placebo, 10–30 mg t.i.d for 14 weeks (30). Nifedipine did not decrease chest pain frequency or intensity but chest pain index (severity x frequency) decreased from 10.3 +/− 2.0 to 3.2 +/− 0.8; p<0.005). A second study compared nifedipine 10 mg t.i.d with placebo in a 4 week randomized crossover study in 16 patients with esophageal motor disorders including achalasia, spasm and nutcracker esophagus (31). 13/16 (81%) patients on nifedipine and 4/16 (25%) on placebo had >50% improvement in ECP. A third placebo controlled study in 8 patients with esophageal spasm showed no differences (32).

Nifedipine – Three double blind placebo-controlled trials (30–32) with quality score of 4,2,4. Evidence fair, (Level II).

Diltiazem

In an open label study of 10 patients with nutcracker esophagus, diltiazem 90 mg qid showed improvement (33). However, in a 10 week randomized, double blind cross-over study of 8 patients with diffuse esophageal spasm, diltiazem was not superior to placebo (34). In another double blind randomized crossover study of 8 weeks, the peristaltic amplitude decreased (p<0.05), and chest pain score decreased (p<0.05) in 14 patients with nutcracker esophagus (35). Generally, these were small studies with significant methodological issues, and GERD was not effectively ruled out.

Diltiazem – Two double blind placebo controlled trials with quality score of 3,3 (34,35). Evidence fair, (Level II).

Nitrates

In an open label trial of 12 patients who received nitroglycerine and long acting nitrates, the five patients who did not have reflux responded well to treatment whereas the seven patients with acid reflux had poor response. There were significant methodological issues including subject selection. Nitrates – one open label study with quality score of 0 (36). Evidence poor, (Level III).

Botulinum Toxin

In an open labeled trial, botulinum toxin A was injected into the gastroesophageal junction in 29 patients; 72% responded with at least 50% reduction in chest pain (37). There was a 79% reduction in the mean chest pain score (from 3.7 to 0.78; p < 0.0001). However, mean duration of response was 7.3+/−4.1 months. In another small open label study of 9 patients with diffuse esophageal spasm (DES) and ECP, 100 IU botulinum toxin A was injected at every 1–1.5 cms above the gastroesophageal junction (38). After 4 weeks, 8/9 (89%) patients showed improvement in total symptom score for 6 months, and some required repeat injections. Botulinum Toxin – Two open-label prospective trials (37,38) with quality score of 0,1. Evidence poor, (Level III).

Lansoprazole

Lansoprazole 30 mg opd for 8 weeks neither improved symptoms nor manometric changes in nutcracker esophagus (39). Lansoprazole – One double blind placebo controlled trial (39) with quality score of 4. Evidence poor, (Level III).

Phosphodiesterase inhibitors

Sildenafil, a phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor was examined in an uncontrolled small study of patients with spastic esophageal motor disorders (42), and the results were inconsistent; acid reflux, and cardiac disease were not excluded. Sildenafil – Open label study, not randomized (40) with quality score of 0 (tables 2a & 2b). Evidence poor, (Level III).

Treatment of esophageal visceral hypersensitivity

Pathophysiology

Esophageal hypersensitivity is a key neurobiological mechanism that causes pain (41,42). Patients with ECP demonstrated 50% lower sensory thresholds when compared to controls together with a hyperreactive and poorly compliant esophagus (43). Also, in 80% of patient’s their typical chest pain was reproduced. More significantly, smooth muscle relaxation with atropine did not improve sensory thresholds or chest pain (44). Likewise, esophageal hypersensitivity was seen in 90% of patients with nutcracker esophagus suggesting sensory dysfunction(29). Together, these findings suggest that esophageal hypersensitivity rather than motor dysfunction is important in ECP. Furthermore, it explained why smooth muscle relaxants by themselves are generally ineffective.

Recent studies have suggested that pain perception in ECP patients may be due to central sensitization (45) and that NMDA blockers may alter chest pain (46). In one controlled study of healthy subjects, citalopram, an SSRI given intravenously, significantly increased sensory thresholds, and prolonged the time for perception of heartburn following acid infusion (47), implying that ECP may be a centrally-mediated. Also adenosine may play a key role in mediating pain; adenosine infusion decreased esophageal sensory thresholds, both in healthy controls and ECP patients (48).

Treatment

Various classes of drugs including imipramine, trazodone, citalopram, sertraline and theophylline have been tried (47,49–56) and summarized in tables 3a & 3b.

Imipramine

Cannon et al postulated a role for mediastinal hypersensitivity (49) in ECP. In a placebo controlled study, 60 patients were randomized for a 3 week trial. Chest pain decreased in 52%, 39% and 1% of patients who received imipramine 50 mg q day, clonidine 0.1 mg qid and placebo respectively, but the reduction was significant (p<0.03) only in the imipramine group. Also the response was independent of esophageal dysfunction or psychiatric comorbidities.

Imipramine - one double blind placebo-controlled trial (49) with quality score of 4. Evidence fair, (Level II).

Trazodone

Twenty-nine patients with chest pain and dysmotility completed a 6-week, RCT of trazodone (100–150 mg/day) (50). Trazodone (n = 15) group reported greater global improvement than placebo (n = 14; p = 0.02) group. However this was not related to manometric improvement which was the primary end point. Trazodone - one double blind placebo-controlled trial (50), quality score 3. Evidence fair, (Level lI).

Sertraline

In a double blind-placebo controlled study sertraline was titrated up to 200 mg daily, in 30 patients for 8 weeks (51). The sertraline showed a significant reduction in pain (p<0.02) when compared to placebo but no differences were seen on Beck Depression Inventory.

Another study assessed whether a combination of psychological treatment (coping skills) plus sertraline, sertraline alone, coping skills alone or placebo was effective in ECP (52). Although there was some benefit in each group, the highest response was seen in the combined therapy (coping skills plus sertraline). Also anxiety and catastrophizing improved suggesting that patients with higher levels of anxiety will benefit the most (52).

A major drawback was that GERD was not excluded. These studies showed that psychiatric comorbidity may influence the outcome of this treatment. Sertraline - two double blind placebocontrolled trial (5,52) with quality score of 4,5. Evidence fair, (Level II).

Venlafaxine

In a 4 week randomized placebo controlled study, 43 patients who received 75mg venlafaxine showed a therapeutic response in 52% of subjects compared to 4% on placebo (53). Also the venlafaxine group showed improvements in body pain and role emotional (p<0.002).

Venlafaxine - one double blind placebo-controlled trial (53) with quality score of 5. Evidence fair, (Level II).

Paroxetine

50 patients were randomized to paroxetine (10–50 mg daily, median dose 30 mg) or placebo for 8 weeks. Patients who received paroxetine showed improvement in the clinical global impression scale (physician-rated) but not in the patient-rated chest pain scale (54). In a second study, 69 patients were randomized to receive paroxetine, CBT or placebo (55) for 16 weeks; paroxetine was no more effective than placebo.

Paroxetine – Two double blind, placebo controlled trials (54,55) with quality score of 5,5. Evidence fair, (Level II) against use.

In a retrospective study (mean follow-up 2.7 y) of antidepressants for the treatment of chest pain, in 21 patients moderate symptom reduction was seen in 17 subjects (81.0%) (56). Of these, 7 (41.2%) were successfully treated continuously and 5 (29.4%) discontinued because of side effects.

Theophylline

Following an open label pilot study of 12 patients (59), a RCT showed that intravenous theophylline decreased esophageal hypersensitivity and, wall reactivity, and improved esophageal distensibility (58). In another randomized placebo controlled crossover study of 25 patients with ECP, theophylline 200 mg orally bid improved chest pain (p<0.03) in 58% of patients compared to 6% in placebo (58). . Theophylline, whose effects are mediated by adenosine receptor antagonism may act as visceral analgesic and smooth muscle relaxant.

Theophylline –two double blind placebo-controlled trials (58) with quality score of 5. Evidence fair, (Level II).

Treatment of ECP using non-pharmacological/behavioral approaches

In one study, 21/25 (84%) with abnormal asophageal manometry had a psychiatric diagnosis compared with eight (31%) subjects with normal manometry (59). Another study by Cannon showed that 38 of 60 (63%) patients with ECP had one or more psychiatric disorders and their ECP responded to imipramine (49). In one study of 441 patients with functional chest pain, the prevalence of panic disorder was 24.5% (60). Whether psychological or psychiatric disorders cause ECP or are commonly associated with this condition remains controversial. A number of approaches have been tried and are summarized in tables 4a & 4b.

Hypnotherapy

In a single blind RCT, 28 patients were randomized to receive hypnotherapy or supporting listening plus placebo medication. The hypnotherapy arm had greater improvement (p=0.008) in chest pain, and a greater reduction in pain intensity (p = 0.046), but not in frequency and in overall well-being when compared to supportive therapy (61).

Hypnotherapy - one single blind randomized-controlled trial (61) with quality score of 3. Evidence poor, (Level III).

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT)

In a small controlled study of CBT versus conventional treatment, 31% (5/17) of subjects were free of symptoms at 12 weeks and 34% (6/17) were partial responders. Depression and anxiety also improved (62). In another study, 37 patients with persistent chest pain heart disease excluded, but not reflux disease, received 12 sessions of CBT. 15/20 completed CBT treatment (75%) versus 10/17 (59%) in the control group. At 3 months, CBT group showed a decrease in pain severity and the number of pain-free days and additionally at 6 months physical and social impairment improved (63). Major drawbacks were the high dropout rate in both treatments questioning the durability of CBT; and GERD was not excluded.

Another RCT compared CBT with usual care in sixty-five patients and showed significant reduction in chest pain frequency but no improvement in concurrent panic disorders (64).

In another RCT, 40 patients received three weekly sessions of CBT. They showed greater improvement with regard to fear of bodily sensations, and some domains of HRQOL (65). However the un-blinded allocation of patients into each therapy indicated significant bias.

An open-label study of psychological treatment “package” (breathing exercises, education, relaxation and graded exposure to activity) in 60 patients with ECP showed significant reduction (p < 0.01) in median chest pain episodes from 6.5 to 2.5 per week. There were significant improvements in anxiety and depression scores (p < 0.05), disability rating (p < 0.0001) and exercise tolerance (p < 0.05) that were maintained for 6 months (66). This study was not blinded and GERD and other sources of chest pain were not excluded.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy - four single blind randomized-controlled trials, (62,63,64,65) with quality score of 2,3,2,3. Evidence fair, (Level II), tables 4a & 4b).

Biofeedback Therapy

Another study involved biofeedback (diaphragmatic exercises), breathing techniques and selfcontrol of stress using galvanic skin resistance feedback. This technique improved symptoms in 5/9 patients with functional chest pain but not in patients with functional heartburn (67).

Biofeedback therapy - one open label trial (67) with quality a score of 1. Evidence poor, (Level III).

Johrei Treatment

39 patients with functional chest pain were randomized to receive 20 minutes of 6 weeks of Johrei treatment (Spiritual Energy healing) or weight-list control (68). When compared to baseline, there was significant reduction in chest pain symptom intensity score (p <.0002) in the Johrei group but not in the control group (20.2 vs. 23.1, P=NS). This pilot study whose mechanism of action is unclear and did not include Sham treatment needs further confirmation.

Johrei Therapy – one randomized, uncontrolled, non-sham study (68) with a quality score of 3. Evidence poor, (Level III).

Although the aforementioned studies provide some evidence for the utility of CBT and other psychological approaches, the precise mechanism for improvement is unclear and robust RCT are lacking.

Treatment of ECP using surgery

One study compared thoracoscopic versus laparoscopic myotomy in 49 (12%) patients with diffuse esophageal spasm and 41 (10%) with nutcracker esophagus and showed no difference in outcome between the two techniques Chest pain improved in 80% of patients with diffuse esophageal spasm but failed in patients with nutcracker esophagus (69). Several surgical approaches have been tried particularly long esophageal myotomy (70), but RCTs are lacking.

Long esophageal myotomy - Nonrandomized, uncontrolled studies (69,70) with quality scores of 0,1. Evidence poor, (Level III).

Discussion

Although patients with ECP or NCCP are commonly encountered in family medicine, cardiology and gastroenterological practices, with an annual incidence of 200,000 patients (2), with regards to its treatment, there is significant dearth of high quality, placebo-controlled, randomized studies. We identified significant methodological problems including the selection of patients, inconsistent definition of ECP across studies and typically small studies. Some have defined this condition as NCCP when a cardiac source has been excluded, others have either included or excluded GERD as a source of ECP, and yet others have excluded a cardiac source, GERD and motility dysfunction. Likewise, the definition of clinical improvement was quite variable. Some have defined improvement based on changes in the frequency of chest pain episodes, few have defined this as >50% improvement in chest pain and others have used improvement in the intensity of chest pain or a global improvement rate or other subjective parameters. Thus, a lack of clear inclusion/exclusion criteria, and a lack of well-defined and standardized patient reported outcome measure has hampered our ability to compare the efficacy and therapeutic usefulness of clinical trials on this topic. It is clear that no one drug or therapeutic modality is likely to work for ECP as it is caused by one or more pathophysiological mechanism(s).

Ideally, treatment of ECP should alleviate not only the symptom(s) but also remedy the underlying pathophysiological mechanism. An evidence-based summary of the efficacy and safety of therapeutic trials in ECP is presented in Tables 1–4. The quality of these studies was assessed using criteria previously established to minimize bias and enhance validity of therapeutic trials (10).

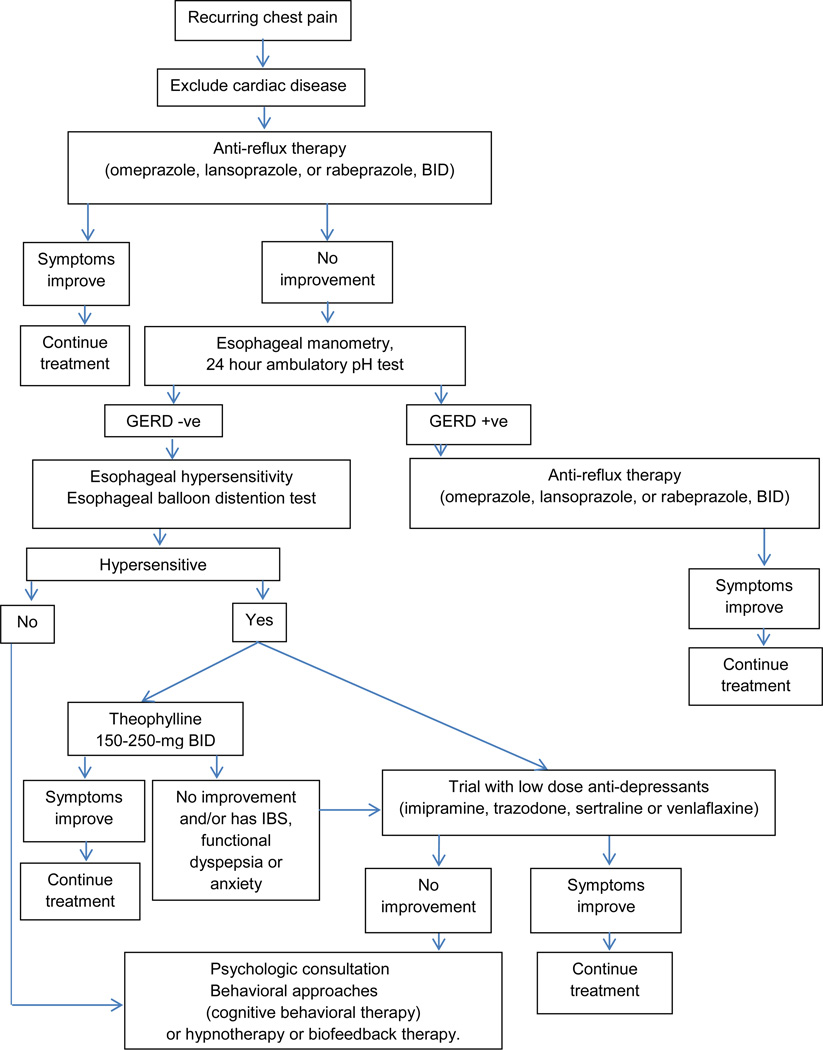

The following recommendations can be made for treatment of ECP based on current evidence summarized above and our clinical experience (Figure 1). After excluding a cardiac source for chest pain, it seems reasonable to begin with anti-reflux therapy (PPI, BID), because GERD affects at least 1/3rd of patients with ECP (6,7). Omeprazole, lansoprazole and rabeprazole appear to be safe and effective (14,18,20–23). If unhelpful, esophageal manometry, 24 hour ambulatory pH test, and esophageal balloon distension test should be considered, and may identify an esophageal source for chest pain in over 75% of patients (6). Alternatively an empirical trial of theophylline 150–250 mg bid should be considered (57, 58).

Fig. 1.

Algorithm for Management of Esophageal Chest Pain

If ineffective, or patient has overlapping features of irritable bowel syndrome, functional dyspepsia or anxiety (42), a trial of low dose anti-depressants, such as imipramine, sertraline or venlafaxine may be considered (49,51–53,56). If none of these approaches help, a psychology consultation together cognitive behavioral therapy or hypnotherapy (62–66) should be considered. There appears to be growing evidence in favor. Surgical approaches such as long thoracomyotomy have undesirable long-term consequences and are best avoided.

Acknowledgement

Dr. SSC Rao was supported by NIH grant No. 2R01 KD57100-05A2. We sincerely appreciate the secretarial assistance of Mrs. Anita Rainwater.

Role of authors: Dr. Coss-Adame and Dr. Rao participated in study design and independently extracted data regarding published studies and developed tables and interpreted data and where there was disagreement consensus was reached. Both authors participated in writing the manuscript. Dr. Erdogan participated in data extraction, development of tables and data interpretation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest: None

References

- 1.Talley NJ. Scope of the problem of functional digestive disorders. Eur J Surg. 1998;582:35–41. doi: 10.1080/11024159850191427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ford AC, Suares NC, Talley NJ. Metaanalysis: the epidemiology of noncardiac chest pain in the community. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34:172–180. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04702.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jerlock M, Welin C, Rosengren A, Gaston- Johannson F. Pain characteristics in patients with unexplained chest pain and patients with ischemic heart disease. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2007;6:130–136. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2006.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sandler RS, Everhart JE, Donowitz M, et al. The burden of selected digestive diseases in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:1500–1511. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.32978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ockene IS, Shay MJ, Alpert JS, et al. Unexplained chest pain in patients with normal coronary arteriograms: a follow-up study of functional status. N Engl J Med. 1980;303:1249–1252. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198011273032201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nasr I, Attaluri A, Coss-Adame E, Rao SS. Diagnostic utility of the oesophageal balloon distension test in the evaluation of oesophageal chest pain. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35:1474–1481. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2012.05103.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fass R, Achem SR. Noncardiac chest pain: epidemiology, natural course and pathogenesis. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2011;17:110–123. doi: 10.5056/jnm.2011.17.2.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Galmiche JP, Clouse RE, Balint A, et al. Functional esophageal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1459–1465. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.08.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials. Is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harris RP, Helfand M, Woolf SH, et al. Current methods of the US Preventive Services Task Force: a review of the process. Am J Prev Med. 2001;20:21–35. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(01)00261-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singh S, Richter J, Hewson EG, Sinclair JW, Hackshaw BT. The contribution of gastroesophageal reflux to chest pain in patients with coronary artery disease. Ann Int Med. 1992;117:824–830. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-117-10-824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Demeester TR, O’Sullivan G, Bermudez G, Midell A, et al. Esophageal function in patients with angina-type chest pain and normal coronary angiograms. Annals of Surg. 1982;196:488–498. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198210000-00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hewson E, Sinclair J, Dalton C, Richter J. 24-hour esophageal pH monitoring: The most useful test for evaluating noncardiac chest pain. Am J Med. 1991;90:576–583. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fass R, Fennerty MB, Ofman JJ, et al. The clinical and economical value of a short course of omeprazole in patients with noncardiac chest pain. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:42–49. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70363-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sifrim D, Zerbib F. Diagnosis and management of patients with reflux symptoms refractory to proton pump inhibitors. Gut. 2012;61:1340–1354. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hemmink GJ, Bredenoord AJ, Weusten BL, et al. Esophageal pH-Impedance Monitoring in Patients with Therapy-Resistant reflux Symptoms: ‘On’ or ‘Off’ Proton Pump Inhibitor? Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:2446–2453. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.02033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kahrilas P, Hughes N, Howden CW. Response of unexplained chest pain to proton pump inhibitor treatment in patients with and without objective evidence of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Gut. 2011;60:1473. doi: 10.1136/gut.2011.241307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cremonini F, Wise J, Moayyedi P, Talley NJ. Diagnostic and therapeutic use of proton pump inhibitors in non-cardiac chest pain: a metaanalysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:1226–1232. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.41657.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Achem SKolts B, MacMath T, Richter J, et al. Effects of omeprazole versus placebo in treatment of noncardiac chest pain and gastroesophageal reflux. Dig Dis Sci. 1997;42:2138–2145. doi: 10.1023/a:1018843223263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pandak WM, Arezo S, Everett S, et al. Short course of omeprazole: a better first diagnostic approach to noncardiac chest pain than endoscopy, manometry, or 24-hour oesophageal pH monitoring. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;35:307–314. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200210000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xia HH, Lai KC, Lam SK, et al. Symptomatic response to lansoprazole predicts abnormal acid reflux in endoscopy-negative patients with non-cardiac chest pain. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17:369–377. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01436.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bautista J, Fullerton H, Briseno M, et al. The effect of an empirical trial of high-dose lansoprazole on symptom response of patients with non-cardiac chest pain--a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover trial. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;19(10):1123–1130. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.01941.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dickman R, Emmons S, Cui H, et al. The effectof a therapeutic trial of high-dose rabeprazole on symptom response of patients with non-cardiac chest pain: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover trial. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22:547–555. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02620.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim JH, Sinn DH, Son HJ, et al. Comparison of one-week and two-week empirical trial with a high-dose rabeprazole in non-cardiac chest pain patients. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24:1504–1509. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.05859.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stahl WG, Beton RR, Johnson CS, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of patients with gastroesophageal reflux and noncardiac chest pain. South Med J. 1994;87:739–742. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199407000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rao SC. How to treat esophageal chest pain. Esophageal Pain. 2010:149–159. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Balaban D, Yamamoto Y, Mittal R, et al. Sustained esophageal contraction: A marker of esophageal chest pain identified by intraluminal ultrasonography. Gastroenterology. 1999;16:29–37. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70225-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pehlivanov N, Liu J, Mittal R. Sustained esophageal contraction: a motor correlate of heartburn symptom. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2001;281:G743–G751. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2001.281.3.G743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mujica V, Mudipalli R, Rao S. Pathophysiology of chest pain in patients with nutcracker esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1371–1377. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03791.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Richter J, Dalton C, Bradley L, Castell D. Oral nifedipine in the treatment of noncardiac chest pain in patients with nutcracker esophagus. Gastroenterology. 1987;93:21–28. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(87)90308-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nasrallah SM, Tommaso CL, Singleton RT, Backhaus EA. Primary esophageal motor disorders: clinical response to nifedipine. South Med J. 1985;78(3):312–315. doi: 10.1097/00007611-198503000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Davies HA, Lewis MJ, Rhodes J, Henderson AH. Trial of nifedipine for prevention of oesophageal spasm. Digestion. 1987;36(2):81–83. doi: 10.1159/000199403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Richter JE, Spurling TJ, Cordova CM, Castell DO. Effects of oral calcium blocker, diltiazem, on esophageal contractions. Studies in volunteers and patients with nutcracker esophagus. Dig Dis Sci. 1984;29:649–656. doi: 10.1007/BF01347298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Drenth JP, Bos LP, Engels LG. Efficacy of diltiazem in the treatment of diffuse oesophageal spasm. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1990;4:411–416. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.1990.tb00487.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cattau EL, Jr, Castell DO, Johnson DA, et al. Diltiazem therapy for symptoms associated with nutcracker esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol. 1991;86(3):272–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Swamy N. Esophageal spasm: clinical and manometric response to nitroglycerine and long acting nitrates. Gastroenterology. 1977;72:23–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miller LS, Pullela S, Parkman H, et al. Treatment of chest pain in patients with noncardiac, nonreflux, nonachalasia spastic esophageal motor disorders using botulinum toxin injection into the gastroesophageal junction. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1640–1646. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05821.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Storr M, Allescher HD, Rösch T, et al. Treatment of symptomatic diffuse esophageal spasm by endoscopic injections of botulinum toxin: a prospective study with long-term follow-up. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:754–759. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Borjesson M, Rolny P, Mannheimer C, Pilhall M. Nutcracker oesophagus: a doubleblind, placebo-controlled, cross-over study of the effects of lansoprazole. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003:1129–1135. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2306.2003.01788.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Eherer AJ, Schwetz I, Hammer HF, et al. Effect of sildenafil on oesophageal motor function in healthy subjects and patients with oesophageal motor disorders. Gut. 2002;50:758–764. doi: 10.1136/gut.50.6.758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hobson AR, Furlong PL, Sarkar S, et al. Neurophysiologic assessment of esophageal sensory processing in noncardiac chest pain. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:80–88. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mudipalli RS, Remes-Troche JM, Andersen L, Rao SS. Functional chest pain: esophageal or overlapping functional disorder. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2007;41:264–269. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000225521.36160.1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rao S, Gregersen H, Hayek B, et al. Unexplained chest pain: the hypersensitive, hyperreactive, and poorly compliant esophagus. Annals Int Med. 1996;124:950–958. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-124-11-199606010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rao S, Hayek B, Summers R. Functional chest pain of esophageal origin: Hyperalgesia or motor dysfunction. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:2584–2589. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.04101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sarkar S, Aziz Q, Woolf C, Hobson A, Thompson D. Contribution of central sensitization to the development of non-cardiac chest pain. Lancet. 2000;356:1154–1159. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02758-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Willert R, Woolf C, Hobson A, Delaney C, Thompson D, Aziz Q. The development and maintenance of human visceral pain hypersensitivity is dependent on the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:683–692. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.11.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Broekaert D, Fischler B, Sifrim D, et al. Influence of citalopram, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, on oesophageal hypersensitivity: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23:365–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02772.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Remes-Troche JM, Chahal P, Mudipalli R, Rao SS. Adenosine modulates oesophageal sensorimotor function in humans. Gut. 2009;58:1049–1055. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.116699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cannon R, Quyyumi A, Mincemoyer R, et al. Imipramine in patients with chest pain despite normal coronary angiograms. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:1411–1419. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199405193302003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Clouse R, Lustman P, Eckert T, et al. Low dose trazadone for symptomatic patients with esophageal contraction abnormalities: a double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 1987;92:1027–1036. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(87)90979-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Varia I, Logue E, O’Conner C, et al. Randomized trial of sertraline in patients with unexplained chest pain of noncardiac origin. Am Heart J. 2000;140:367–372. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2000.108514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Keefe FJ, Shelby RA, Somers TJ, et al. Effects of coping skills training and sertraline in patients with non-cardiac chest pain: A randomized controlled study. Pain. 2011;152:7307–7341. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.08.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lee H, Kim JH, Min BH, et al. Efficacy of venlafaxine for symptomatic relief in young adult patients with functional chest pain: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:1504–1512. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Doraiswamy PM, Varia I, Hellegers C, et al. A randomized controlled trial of paroxetine for noncardiac chest pain. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2006;39:15–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Spinhoven P, Van der Does AJ, Van Dijk E. Van Rood YR Heart-focused anxiety as a mediating variable in the treatment of noncardiac chest pain by cognitive-behavioral therapy and paroxetine. J Psychosom Res. 2010;69:227–235. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2010.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Prakash C, Clouse R. Long-term outcome from tricyclic anti-depressant therapy of functional chest pain. Dig Dis Sci. 1999;44:2373–2379. doi: 10.1023/a:1026645914933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rao S, Mudipalli R, Mujica V, et al. An open-label trial of theophylline for functional chest pain. Dig Dis Sci. 2002;47:2763–2768. doi: 10.1023/a:1021017524660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rao SS, Mudipalli RS, Remes-Troche JM, et al. Theophylline improves esophageal chest pain-a randomized, placebo-controlled study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:930–938. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Clouse R, Lustman P. Psychiatric illness and contraction abnormalities of the esophagus. N Engl J Med. 1983;309:1337–1342. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198312013092201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fleet R, Dupuis G, Marchand A, Bureolle D, et al. Panic disorder in emergency department chest pain patients: Prevalence, comorbidity, suicidal ideation and physician recognition. Am J Med. 1996;101:371–380. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(96)00224-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jones H, Cooper P, Miller V, et al. Treatment of non-cardiac chest pain: a controlled trail of hypnotherapy. Gut. 2006;55:1403–1408. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.086694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Klimes I, Mayou RA, Pearce MJ, et al. Psychological treatment for atypical non-cardiac chest pain: a controlled evaluation. Psychol Med. 1990;20:605–611. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700017116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mayou RA, Bryant BM, Sanders D, et al. A controlled trial of cognitive behavioural therapy for non-cardiac chest pain. Psychol Med. 1997;27:1021–1031. doi: 10.1017/s0033291797005254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Van Peski-Oosterbaan AS, Spinhoven P, Van der Does AJ, et al. Cognitive change following cognitive behavioural therapy for non-cardiac chest pain. Psychother Psychosom. 1999;68:214–220. doi: 10.1159/000012335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jonsbu E, Dammen T, Morken G, et al. Short-term cognitive behavioral therapy for non-cardiac chest pain and benign palpitations: a randomized controlled trial. J Psychosom Res. 2011;70:117–123. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2010.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Potts SG, Lewin R, Fox KA, Johnstone EC. Group psychological treatment for chest pain with normal coronary arteries. QJM. 1999;92:81–86. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/92.2.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shapiro M, Shanani R, Taback H, et al. Functional chest pain responds to biofeedback treatment but functional heartburn does not: what is the difference? Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;24:708–714. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3283525a0c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gasiorowska A, Navarro-Rodriguez T, Dickman R, et al. Clinical trial: the effect of Johrei on symptoms of patients with functional chest pain. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29:126–134. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03859.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Patti MG, Gorodner MV, Galvani C, Tedesco P, et al. Spectrum of esophageal motility disorders: implications for diagnosis and treatment. Arch Surg. 2005;140:442–448. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.140.5.442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Henderson RD, Ryder D, Marryatt G. Extended esophageal myotomy and short total fundoplication hernia repair in diffuse esophageal spasm: five-year review in 34 patients. Ann of Thorac Surg. 1987;43:25–31. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(10)60161-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]