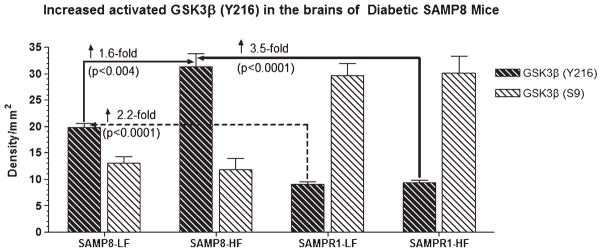

Fig. 8.

Western blot of brain samples derived from SAMP8 or SAMPR1 mice fed with high fat (HF) or low fat (LF) diets showing the reactivity for glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK3β) phosphorylated at tyrosine 216 site-activated form of GSK3β (anti-Y216 GSK3β) and at serine 9 site-inactive form of GSK3β (anti-S9 GSK3β) (BioSource International). In general, density for activated GSK3β (Y216) is greater in the brains of SAMP8 mice than that of SAMPR1 mice. By contrast, density for inactive form of GSK3β (S9) is greater in the brains of SAMPR1 mice than that of SAMP8 mice. HF treatment did not affect the reaction for inactive GSK3β (S9) in the brains of SAMP8 mice. HF treatment increased the density for activated GSK3β (Y216) only in the brains of SAMP8 mice, but not in the brains of SAMPR1 mice, indicating that experimental induction of type 2diabetes in SAMP8 mice promotes abnormal phosphorylation of tau. Densitometric analysis showed that compared to LF-fed non-diabetic SAMP8 mice, the levels of GSK3β (Y216) increased by 1.6-fold (p < 0.004) in HF-fed diabetic SAMP8 mice. Compared to LF-or HF-fed non-diabetic or diabetic SAMPR1 mice, the levels of GSK3β (Y216) increased by 2.2-fold (p < 0.0001) in HF-fed diabetic SAMP8 mice.