Abstract

Metal hyperaccumulating plants are able to store very large amounts of metals in their shoots. There are a number of reasons why it is important to be able to introduce metal hyperaccumulation traits into non-accumulating species (e.g., phytoremediation or biofortification in minerals) and to engineer a desired level of accumulation and distribution of metals. Metal homeostasis genes have therefore been used for these purposes. Engineered accumulation levels, however, have often been far from expected, and transgenic plants frequently display phenotypic features not related to the physiological function of the introduced gene. In this review, we focus on an aspect often neglected in research on plants expressing metal homeostasis genes: the specific regulation of endogenous metal homeostasis genes of the host plant in response to the transgene-induced imbalance of the metal status. These modifications constitute one of the major mechanisms involved in the generation of the plant's phenotype, including unexpected characteristics. Interestingly, activation of so-called “metal cross-homeostasis” has emerged as a factor of primary importance.

Keywords: zinc (Zn), cadmium (Cd), nickel (Ni), hyperaccumulation, heavy metal, plant transformation, overexpression

Introduction

Engineered metal uptake, organ- and tissue-specific distribution, and tolerance in plants contribute to phytoremediation/phytoextraction (use of plants to remove metals from contaminated soils) and mineral biofortification (optimization of micronutrient contents in plant-derived food and exclusion of toxic metals). For both it is crucial to modify the metal concentration in plant parts (Palmgren et al., 2008; Verbruggen et al., 2009). For these purposes, plants have been transformed using metal homeostasis genes involved in uptake, compartmentalization, long-distance transport, and chelation of metals.

Contrary to expectations, the resulting plants expressing introduced genes have displayed characteristics unrelated to the physiological functions which these genes perform in their species of origin. For example, transformation with transporters not involved in metal uptake or with other metal homeostasis genes may lead to: (i)induction of an endogenous metal uptake system (e.g., Song et al., 2003; Thomas et al., 2003; Martinez et al., 2006; Gorinova et al., 2007; Korenkov et al., 2007); (ii)decreased uptake/accumulation, alteration of the status of a range of other metals, their distribution, and sensitivity to them (e.g., Harada et al., 2001; Li et al., 2004; Gasic and Korban, 2007; Wojas et al., 2008, 2009; Grispen et al., 2011; Barabasz et al., 2012, 2013 see also reviews by Kärenlampi et al., 2000; Pilon-Smits and Pilon, 2002; Eapen and D'Souza, 2005; Seth, 2012). The development of unexpected features is a manifestation of changes in a range of host-plant endogenous molecular and physiological pathways due to expression of the introduced gene/genes. As these alterations substantially contribute to generation of the plant's phenotype, understanding the underlying mechanisms is crucial for better planning of future modifications of metal accumulation and tolerance, and for Environmental Risk Assessment of genetically modified plants.

Increasing amounts of evidence indicate that molecular mechanisms governing the maintenance of metal homeostasis are not specific for each metal, but are interconnected by common pathways. This phenomenon, termed “cross-homeostasis,” results from regulation by several metals of the same transcription factor, the same metal transporter (which mediates—with different affinities—the translocation of more than one metal ion), or metal chelator (Sinclair and Krämer, 2012). In studies aimed at deciphering the mechanisms through which the metal-related phenotype of plants expressing a foreign gene is generated, specific regulation of the endogenous metal cross-homeostasis network of the host plant appeared to be a consequence of the expression of the transgene, and one of the major causes of the development of various characteristic features of transformants.

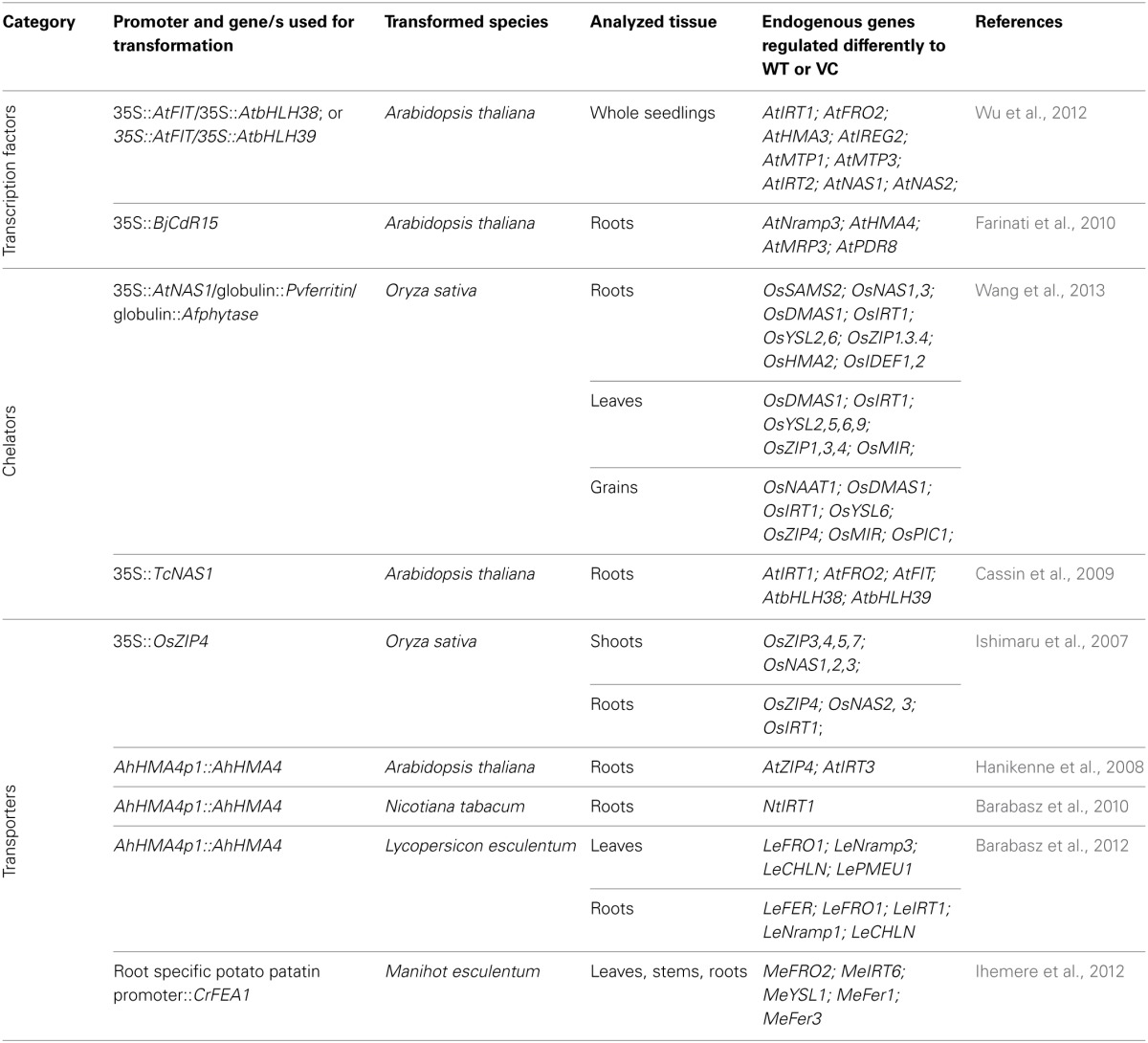

Only a few studies were performed so far to link modifications of an endogenous metal homeostasis network due to transgene expression with development of unforeseen characteristics of transgenic plants. This review will highlight the importance of understanding these processes for better engineering of metal-related features. Table 1 provides a summary of the studies discussed in the review.

Table 1.

List of transformations discussed in the review; shown are the genes and species used for transformation, and identified metal-homeostasis genes differentially expressed in transformants relative to wild-type (WT) or vector-controls (VC).

Alteration of endogenous metal homeostasis mechanisms of plants expressing transgenes involved in metal homeostasis

Expression of transcription factors

IRT1 (ZRT-IRT-like Protein, ZIP family) mediates Fe2+ uptake by roots and, with a lower affinity, of Zn2+, Mn2+, Cd2+. In Arabidopsis thaliana, AtIRT1 and AtFRO2 (root surface ferric chelate reductase) are components of the Strategy I Fe-deficiency-induced Fe-acquisition system. Their expression is regulated by FIT (Fer-like Deficiency-Induced Transcription Factor), that forms heterodimers with one of the two transcription factors, AtbHLH38 or AtbHLH39 (Puig et al., 2007; Sinclair and Krämer, 2012).

Enhanced Cd tolerance in the model plant Arabidopsis was engineered by co-expression of transcription factors: 35S::AtFIT with 35S:: AtbHLH38 (ox29/38) or 35S::AtFIT with 35S::AtbHLH39 (ox29/39) (Wu et al., 2012). By studying the impact of transgene expression on the transcript level of chosen endogenous metal homeostasis genes, it was shown that their distinct regulation contributes to gaining new features related to a plant's response to Cd. In transformed plants, three fundamental changes that contribute to increased Cd tolerance were found at the molecular level.

First, transgenic plants had higher Fe levels in shoots (known to alleviate Cd-toxicity) resulting from greater Fe-uptake, associated with higher expression of Fe-deficiency inducible Fe-uptake genes AtIRT1 and AtFRO2, and from more efficient upward translocation through unknown mechanisms.

Second, Cd concentrations were higher in roots, but lower in shoots. It was suggested that increased accumulation of Cd in roots resulted from detected constitutive enhancement of expression of genes known for their involvement in the retention of Cd in vacuoles and intracellular vesicles, such as AtHMA3 (Heavy-metal ATPase) and Cd-regulated AtIRT2 (Wu et al., 2012). Moreover, up-regulation of other Fe-deficiency response genes such as AtIREG2 (Iron Regulated Gene, known to be co-regulated with AtIRT1) and AtMTP3 (Metal Tolerance Protein) were noted. They contribute to metal homeostasis and their enhanced expression under low Fe status results from Fe-deficiency dependent enhancement of uptake of other divalent metal cations mediated by the Fe-uptake protein AtIRT1, which is a side effect of its low substrate specificity (Arrivault et al., 2006; Schaaf et al., 2006; Ricachenevsky et al., 2013).

Third, expression of NAS1 and NAS2 (nicotianamine synthase) was up-regulated and concentrations of metal-chelator nicotianamine (NA) were higher, indicating NA involvement in Cd-tolerance.

Cd tolerance and Cd translocation to shoots were also enhanced by overexpression of bZIP transcription factor 35S::BjCdR15 from Brassica juncea using the 35S promoter (Farinati et al., 2010) in Arabidopsis. It was shown that at longer exposure to Cd, the expression levels of AtNramp3 (Natural resistance-associated macrophage protein), AtHMA4, AtMRP3 (Multidrug resistance-associated proteins from subfamily ABC) and AtPDR8 (transporter from subfamily ABC) were significantly different in transgenic plants than in the wild-type. Interestingly, enhanced translocation of Cd to shoots of transformants was accompanied by lower expression of AtHMA4 than in the wild-type. Since HMA4 controls Zn/Cd root-to-shoot translocation (Hussain et al., 2004; Wong and Cobbett, 2009), the detected enhancement of Cd concentrations in transgenic shoots is likely based on an HMA4-independent mechanism.

Expression of chelator synthesis genes

Nicotianamine (NA), a non-proteinogenic amino acid, chelates metal ions, including Fe3+, Fe2+, Zn2+, Ni2+, Mn2+ (Curie et al., 2009). It is involved in processes regulating metal homeostasis and cross-homeostasis. Therefore, NAS genes were frequently used to engineer metal distribution and enhanced tolerance. The phenotypes of NAS-expressing plant species appeared to be very different with respect to alterations of Fe concentration/distribution, tolerance to low-to-high Fe levels, and responses to other metals (e.g., Ni, Zn, Mn), which indicated modifications of endogenous metal cross-homeostasis mechanisms.

The impact of transgene expression on endogenous metal homeostasis genes was investigated in two species, A. thaliana and Oryza sativa, which differ in Fe-uptake systems. As a dicot, Arabidopsis has reduction-based Strategy I. Grasses, e.g., rice or corn, use chelation-based Strategy II (roots release mugineic acid-MA, a Fe3+-chelating compound, subsequently taken up by YSL transporters). Rice, as an exception, also has the Strategy I system (Ishimaru et al., 2006). The 35S::TcNAS from Thlaspi caerulescens was overexpressed in Arabidopsis (Pianelli et al., 2005; Cassin et al., 2009). In rice, 35S::AtNAS1 was expressed together with Pvferritin (Fe-storage protein) and Afphytase (catalyzing hydrolysis of phytic acid releasing chelated metals) under the rice seed storage globulin promoter (Wirth et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2013).

In both NA-overaccumulating transformants, distinct features were accompanied by different modifications of the expression of metal homeostasis genes, however, certain common changes emerged as well. In both transgenic plants enhanced expression of the Fe-deficiency induced Fe-uptake systems was reported, indicating increased Fe-deficiency status.

In TcNAS-expressing Arabidopsis, transcript level of AtIRT1, AtFRO2 and three transcription factor genes (AtFIT1, AtbHLH38, and AtbHLH39) was higher than in the wild-type (Cassin et al., 2009). Overinduction of the Fe-uptake system increased the concentration of Zn and Mn in NAS-expressing Arabidopsis. Detected up-regulation of the Zn-transporter gene AtZIP3 in these plants was interpreted as induction of endogenous metal transport mechanisms, to overcome the metal ion imbalances generated by expression of TcNAS.

In transgenic rice enhanced Fe uptake and translocation to grains (accumulating more Fe than wild-type) were noted (Wang et al., 2013). It was accompanied by induction of the Strategy I uptake system (as expression of OsIRT1 was enhanced) but also by the Strategy II Fe-uptake system. Upregulation of genes from the MAs biosynthesis pathway were noted, including OsSAMS2 (methionine synthetase); OsNAAT1 (nicotianamine aminotransferase); OsDMAS1 (deoxymugineic acid synthase), OsNAS1,OsNAS2,OsNAS3, and YSL transporters. Detailed tests performed at different developmental stages of transgenic and wild-type plants grown at high Fe and low Fe, shown also changes in expression of several metal homeostasis genes due to expression of AtNAS1/Pvferritin/Afphytase in rice. These include primarily OsZIP1, OsZIP3, OsZIP4, OsZIP8, OsYSL2, OsYSL5, OsYSL6 encoding transporters which mediate translocation of different metals with different affinity.

Thus, ectopic expression of TcNAS in Arabidopsis, and AtNAS1/Pvferritin/Afphytase in rice, led to deregulation of homeostasis of several metals and induced endogenous metal-homeostasis molecular mechanisms to cope with these changes, thus contributing to the development of new plant's traits. Although the complete picture is not clear at the current stage of investigation, obtained results indicate that expression of AtNAS1/Pvferritin/Afphytase in rice contributes to better utilization of overproduced NA and DMA, and higher Fe storage capacity via ferritin, than the expression of only TcNAS in Arabidopsis. In the latter case, unwanted characteristics developed likely due to generation of more severe imbalances, primarily at the cellular level.

Expression of metal transporters

ZIP4

OsZIP4 from Oryza sativa is a Zn-deficiency-inducible gene expressed in the vasculature of roots and leaves. It encodes a plasma-membrane-localized protein responsible for Zn transport within plants, but not for its uptake from soil (Ishimaru et al., 2005). The overexpression of 35S::OsZIP4 in rice altered numerous endogenous pathways leading to 10-fold higher Zn concentrations in roots, 5-fold lower in shoots (accompanied by Zn-deficiency symptoms) and 50% reduction in grains (Ishimaru et al., 2007).

The comparison of transcription profiles of transgenic rice with vector-controls showed up-regulation of 236 genes in Zn-deficient shoots, of which 188 are Zn-deficiency-inducible genes. In contrast, out of 235 genes up-regulated in transgenic roots (accumulating high Zn) 102 genes are down-regulated by Zn-deficiency in vector control plants. Expression of 35S::OsZIP4 deregulated also the expression of the endogenous OsZIP4. At control conditions, its transcript level was significantly lower in the roots and higher in the shoots, as compared with the vector control. Moreover, 35S::OsZIP4-expression induced Fe-uptake and resulted in higher Fe concentrations in roots and shoots.

Thus, the transport activity of 35S::OsZIP4 in tissues other than those targeted in wild-types leads to substantial modification of Zn/Fe status at the cellular and tissue levels, stimulates uptake of Zn and Fe, and induces the Zn/Fe cross-homeostasis network to reconstitute the ion balance. Such modifications contribute to changes in Zn/Fe accumulation.

HMA4

It was shown that HMA4, a P1B-ATPase involved in Zn loading into xylem vessels, is responsible for control of Zn translocation to shoots both in non-accumulating A. thaliana and in the Zn-hyperaccumulator, A. halleri (Hussain et al., 2004; Hanikenne et al., 2008). Therefore HMA4 was used for transformation to increase Zn levels in shoots of non-accumulating species. AhHMA4 from A. halleri was expressed under its endogenous promoter in three plant species: A. thaliana, tobacco, and tomato (Hanikenne et al., 2008; Barabasz et al., 2010, 2012). Although the experimental conditions were very different (e.g., growth media, metals, time of exposure), the results provide new information about the modifications of endogenous molecular traits that contribute to the generation of the characteristic new features of genetically modifies plants.

The expression of AhHMA4p1::AhHMA4 in A. thaliana introduced several traits of the Zn-hyperaccumulator (Hanikenne et al., 2008). First, loading of Zn into xylem vessels was enhanced. Second, the expression pattern of AhHMA4p1::AhHMA4 in A. thaliana followed that characteristic of A. halleri. Moreover, similarly as in A. halleri, in transgenic A. thaliana roots the expression of Zn-deficiency-responsive genes AtZIP4 and AtIRT3 was enhanced. The increased expression of these genes in A. halleri, which is driven by Zn-deficiency generated by high activity of AhHMA4 contributes to the Zn-hyperaccumulation phenotype. Nevertheless, in AhHMA4-expressing A. thaliana exposed to 5 μM Zn, the shoot metal concentration was only slightly enhanced (1.16-fold). Increases in Zn concentrations in shoots to extents not characteristic of hyperaccumulators were also found in tobacco and tomato expressing AhHMA4p1::AhHMA4 (Barabasz et al., 2010, 2012), but not at all doses in the range of tested Zn medium concentrations (from 0.5 to 500 μM Zn). Dose-dependence of metal root/shoot distribution, different in transgenic and wild-type, has also been reported for plants expressing 35S::AtHMA4 as well as other metal transporters such as CAXs, AtECA3 and HvHMA2 (Korenkov et al., 2007; Barabasz et al., 2011, 2013; Siemianowski et al., 2011). The Zn-supply dependent modifications of Zn concentrations in the shoots of plants expressing HMA2, HMA4, and ECA3 were listed in the Table 2. It has previously been reported for A. thaliana, A. halleri, and T. caerulescens that distinct homeostatic mechanisms underlie low, sufficient, and excess Zn statuses (Talke et al., 2006; van de Mortel et al., 2006). Therefore, phenomenon of the metal-supply dependent metal-accumulation pattern detected in transgenic plants was thought to result from different molecular backgrounds at varying metal statuses, against which the expression of a transgene takes place.

Table 2.

Zn-supply dependent modifications of Zn concentration in the shoots of plants expressing genes listed in the first column (relative to wild-type).

| Promoter/gene used for transformation | Transformed species | Alterations of Zn concentration in shoots of transgenic plants (relative to wild-type) exposed to 0.5; 1; 10; 100; 150; and 200 μM Zn | References | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5 μM Zn | 1 μM Zn | 10 μM Zn | 100 μM Zn | 150 μM Zn | 200 μM Zn | |||

| 35S::AtHMA4 | Tobacco | ND | – | H | ND | – | ND | Siemianowski et al., 2011 |

| 35S::AtHMA4-Cterm | Tobacco | H | – | H | L | – | L | |

| 35S::AtHMA4-trunc | Tobacco | ND | – | ND | L | – | L | |

| AhHMA4p1::AhHMA4 | Tobacco | H* | L | ND | – | ND | ND | Barabasz et al., 2010 |

| AhHMA4p1::AhHMA4 | Tomato | – | ND | H | – | – | – | Barabasz et al., 2012 |

| 35S::HvHMA2 | Tobacco | – | ND | H | ND | – | – | Barabasz et al., 2013 |

| 35S::AtECA3 | Tobacco | ND | – | L | – | – | – | Barabasz et al., 2011 |

Changes in Zn concentrations in shoots of transgenic tobacco or tomato (relative to wild-type) due to expression of a given gene, grown in the presence of 0.5; 1; 10; 100; 150; and 200 μM Zn, were marked as: ND, no difference between transgenic and wild-type plant; H, higher in transgenic plants than in wild-type; L, lower in transgenic plants than in wild-type; –, not examined;

, only in upper leaves.

At varying metal levels in the medium, the expression pattern of endogenous metal homeostasis genes in transgenic plants also differed from wild-type. For example, in tobacco transformed with AhHMA4p1::AhHMA4, the expression of NtIRT1 was enhanced specifically upon Zn-deficiency and at 10 μM Zn when compared with control conditions or with the NtIRT1 transcript level in the wild-type (Barabasz et al., 2010). This suggests that the transcript abundance of the Fe/Zn uptake gene NtIRT1 undergoes differential regulation in transformants over a range of Zn exposures. This might result from distinct Zn/Fe-statuses under these conditions in connection with differential modification of the endogenous metal homeostasis network resulting from expression of the transgene. Similarly, in tomato expressing AhHMA4p1::AhHMA4 there was a substantial difference in the expression levels of LeFER, LeIRT1, LeNramp1, LeCHLN (LeNAS), and LePMEU1 (pectinmethylesterase) between transgenic and wild-type plants exposed to low and high Zn (Barabasz et al., 2012).

It was found that the expression of HMA4 in tomato, tobacco, and Arabidopsis makes plants more sensitive to Zn (Hanikenne et al., 2008; Barabasz et al., 2010, 2012; Siemianowski et al., 2011). Expression of the Zn export gene 35S::AtHMA4 in tobacco and AhHMA4p1::AhHMA4 in tomato led to overloading of the apoplast with Zn (Barabasz et al., 2012, Siemianowski et al., 2013). In 35S::AtHMA4-expressing tobacco enhanced Zn concentrations in the apoplast were shown to be critical for development of leaf necrosis—symptoms of Zn-sensitivity (Siemianowski et al., 2013). Molecular consequences of HMA4 expression were also detected within the cell wall. In AhHMA4p1::AhHMA4-expressing tomato, a 20-fold higher Zn concentration in the apoplast was associated with up-regulation of LePMEU1 (Barabasz et al., 2012), the cell-wall remodeling pectinmethylesterase (Pelloux et al., 2007). These indicate that transgene-induced processes leading to cell-wall modifications might significantly contribute to the response of transgenic plants to metals. A role for pectinmethylesterase in the apoplastic storage of Zn or Hg had been already suggested (Heidenreich et al., 2001; Hassinen et al., 2007). Moreover, studies performed on AhHMA4p1::AhHMA4-expressing tomato showed that higher than wild-type sensitivity to excess Zn was accompanied by: (i) decreased Fe concentrations in leaves; (ii) enhanced expression of Fe-deficiency-induced LeFRO1, LeIRT1, and LeFER (a functional ortholog of AtFIT); (iii) higher activity of FRO; (iv) higher transcript abundance of LeNramp1, which is a transporter involved in redistribution of iron from vacuolar stores under Fe-limiting conditions (Bereczky et al., 2003); (v) higher LeCHLN expression. Thus, disturbances in apoplast/symplast Zn-status due to expression of Zn-export genes (e.g., HMA4) seem to be a key factor inducing ion imbalances at the cellular/tissue level. Subsequent modifications of transcription profiles of metal homeostasis genes in engineered plants underlie development of characteristic features unrelated to the physiological functions of introduced genes.

Another detected unforeseen characteristic feature resulting from the ectopic expression of a transgene, was decreased Cd uptake/accumulation in roots and shoots of tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum v.Xanthi) expressing 35S::AtHMA4 (Siemianowski et al., 2011). For understanding the mechanisms underlying this Cd-dependent phenotype and to help predict the consequences of a transgene expression for potential phytoremediation/biofortification-based strategies, microarray analysis was performed to identify metal homeostasis genes that were differentially expressed in roots of Cd-exposed AtHMA4-expressing tobacco relative to the wild type (Siemianowski et al., 2014). It was shown that restriction of Cd uptake/accumulation in AtHMA4-expressing plants was not related to downregulation of genes involved in Cd uptake. The expression level of NtIRT1 and NtZIP1 were higher in transgenic plants indicating generated Fe- and Zn-deficiency status due to AtHMA4 expression. Interestingly, due to ectopic expression of 35S::AtHMA4 the physical apoplastic barrier within the external cell layer developed, which was considered responsible for the reduction of Cd uptake/accumulation. Biochemical and microscopic analysis of roots showed that expression of AtHMA4 caused an induction of cell wall lignification in the external cell layers that was accompanied by enhanced H2O2 accumulation. These changes were accompanied by the upregulation of genes involved in cell wall lignification (NtHCT, NtOMET, NtPrx11a).

Implications

A challenge in engineering metal tolerance, accumulation and distribution in plants is to eliminate unwanted, unfavorable features. The observed phenotypes are unexpected based solely on the molecular function of the protein encoded by the transgene (for example Zn transport), but result from a complex interaction between this molecular function, the expression pattern and strength of the transgene and the host response to the modification of the metal homeostasis network.

Recent studies indicate that deregulation of a metal balance due to activity of a protein encoded by a gene used for transformation (primarily in cells/tissues other than in the species from which the gene was cloned) contribute to generation of plant's characteristics. Changed metal status at a cellular/tissue/organ level activates endogenous metal homeostasis mechanisms to combat the generated imbalance. Thus, the secondary effects induced by expression of introduced genes are, in fact, an integral part of the mechanisms underlying development of unwanted features, although usually they have remained unstudied.

Ectopic expression under a strong constitutive promoter (e.g., CaMV35S) disturbs status of metal/metals, consequently metal homeostasis networks, everywhere in a plant (Siemianowski et al., 2013). Localized transgene expression under tissue-/organ-specific promoters should result in modifications only in targeted tissues/organs, however, we must know where exactly in a host plant its expression takes place or where proteins accumulate. In the majority of studies this was only assumed, without direct demonstration. This is a challenge for future studies.

Another difficulty in engineering a metal-related trait results from the metal cross-homeostasis phenomenon. It is becoming evident that changes in the status of one metal due to the expression of a chosen gene/genes generate multifactorial responses related to other metals as part of the regulation of an endogenous cross-homeostasis network. In targeted expression, activation of cross-homeostasis mechanisms still takes place also in non-targeted organs leading to effects poorly recognized. Therefore, in devising strategies for engineering a specific metal-related feature, it is necessary to keep in mind that broad spectrums of metals and processes should be investigated. For that purpose, identification and use of marker genes (ideally regulated exclusively or primarily by one metal) could be of help. Current knowledge is very limited, but available data indicate that the Strategy I Fe uptake system is affected in plants transformed with different genes involved in the metabolism of Zn, Fe and other metals, likely as a result of modified cellular/tissue/organs metal-status.

The complexity of difficulties in engineering metal accumulation/distribution is also manifested by the phenomenon of metal-supply-dependent metal distribution, in transgenic plants (phenomenon known for the wild-type). Contribution of the interplay between transgene expression/protein activity and the host plant metal homeostasis network was suggested. It is, therefore, necessary to use a broad range of metal concentrations for tests, otherwise modifications resulting from transgene expression could be overlooked. This also points to difficulties in engineering a plant displaying the desired metal-related trait (e.g., hyperaccumulation) under varying conditions of metal supply.

Moreover, it is worth noting that molecular analysis of modifications of endogenous metal homeostasis pathways altered in transgenic plants can provide knowledge not only about mechanisms generating the phenotype, but also about the regulation of cross-homeostasis mechanisms by identification of sets of genes playing a key role in this phenomenon.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Supported by grant 814/N-COST/2010/0. Work related to COST-Action-FA0905.

References

- Arrivault A., Senger T., Krämer U. (2006) The Arabidopsis metal tolerance protein AtMTP3 maintains metal homeostasis by mediating Zn exclusion from the shoot under Fe deficiency and Zn oversupply. Plant J. 46, 861–879 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02746.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barabasz A., Krämer U., Hanikenne M., Rudzka J., Antosiewicz D. M. (2010). Metal accumulation in tobacco expressing Arabidopsis halleri metal hyperaccumulation gene depends on external supply. J. Exp Bot. 61, 3057–3067 10.1093/jxb/erq129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barabasz A., Mills R. F., Trojanowska E., Williams L. E., Antosiewicz D. M. (2011). Expression of AtECA3 in tobacco modifies its response to manganese, zinc and calcium. Environ. Exp. Bot. 72, 202–209 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2011.03.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barabasz A., Wilkowska A., Ruszczyñska A., Bulska E., Hanikenne M., Czarny M., et al. (2012). Metal response of transgenic tomato plants expressing P1B-ATPase. Physiol. Plant. 145, 315–331 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2012.01584.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barabasz A., Wilkowska A., Tracz K., Ruszczyñska A., Bulska E., Mills R. F., et al. (2013). Expression of HvHMA2 in tobacco modifies Zn-Fe-Cd homeostasis. J. Plant Physiol. 170, 1176–1186 10.1016/j.jplph.2013.03.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bereczky Z., Wang H.-Y., Schubert V., Ganal M., Bauer P. (2003). Differential regulation of nramp and irt metal transporter genes in wild type and iron uptake mutants of tomato. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 24697–24704 10.1074/jbc.M301365200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassin G., Mari S., Curie C., Briat J.-F., Czernic P. (2009). Increased sensitivity to iron deficiency in Arabidopsis thaliana overaccumulating nicotianamine. J. Exp. Bot. 60, 1249–1259 10.1093/jxb/erp007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curie C., Cassin G., Couch D., Divol F., Higuchi K., Le Jean M., et al. (2009). Metal movement within the plant: contribution of nicotianamine and yellow stripe 1-like transporters. Ann. Bot. 103, 1–11 10.1093/aob/mcn207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eapen S., D'Souza S. F. (2005). Prospects of genetic engineering of plants for phytoremediation of toxic metals. Biotechnol. Adv. 23, 97–11 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2004.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farinati S., DalCorso G., Varotto S., Furini A. (2010). The Brassica juncea BjCdR15, an ortholog of Arabidopsis TGA3, is a regulator of cadmium uptake, transport and accumulation in shoots and confers cadmium tolerance in transgenic plants. New Phytol. 185, 964–978 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.03132.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasic K., Korban S. S. (2007) Expression of Arabidopsis phytochelatin synthase in Indian mustard (Brassica juncea) plants enhances tolerance for Cd and Zn. Planta 225, 1277–1285 10.1007/s00425-006-0421-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorinova N., Nedkovska M., Todorovska E., Simova-Stoilova L., Stoyanova Z., Georgieva K., et al. (2007). Improved phytoaccumulation of cadmium by genetically modified tobacco plants (Nicotiana tabacum L.). Physiological and biochemical response of the transformants to cadmium toxicity. Environ. Pollut. 145, 161–170 10.1016/j.envpol.2006.03.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grispen V. M. J., Hakvoort H. W. J., Bliek T., Verkleij J. A. C., Schat H. (2011). Combined expression of the Arabidopsis metallothionein MT2 and the heavy metal transporting ATPase HMA4 enhances cadmium tolerance and the root to shoot translocation of cadmium and zinc in tobacco. Environ. Exp. Bot. 72, 71–76 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2010.01.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hanikenne M., Talke I. N., Haydon M. J., Lanz C., Nolte A., Motte P., et al. (2008). Evolution of metal hyperaccumulation required cis-regulatory changes and triplication of HMA4. Nature 453, 391–395 10.1038/nature06877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harada E., Choi Y.-E., Tsuchisaka A., Obata H., Sano H. (2001). Transgenic tobacco plants expressing a rice cysteine synthase gene are tolerant to toxic levels of cadmium. J. Plant Physiol. 158, 655–661 10.1078/0176-1617-00314 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hassinen V. H., Tervahauta A. I., Halima P., Plessl M., Peräniemi S., Schat H., et al. (2007). Isolation of Zn-responsive genes from two accessions of the hyperaccumulator plant Thlaspi caerulescens. Planta 225, 977–989 10.1007/s00425-006-0403-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidenreich B., Mayer K. J., Sandermann H., Ernst D. (2001). Mercury-induced genes in Arabidopsis thaliana: identification of induced genes upon long-term mercuric ion exposure. Plant Cell Environ. 24, 1227–1234 10.1046/j.0016-8025.2001.00775.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hussain D., Haydon M. J., Wang Y., Wong E., Sherson S. M., Young J., et al. (2004), P-type ATPase heavy metal transporters with roles in essential zinc homeostasis in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 16, 1327–1339 10.1105/tpc.020487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ihemere U. E., Narayanan N. N., Sayre R. T. (2012). Iron biofortification and homeostasis in transgenic cassava roots expressing the algal iron assimilatory gene, FEA1. Front. Plant Sci. 3:171 10.3389/fpls.2012.00171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishimaru Y., Masuda H., Suzuki M., Bashir K., Takahashi M., Nakanishi H., et al. (2007). Overexpression of the OsZIP4 zinc transporter confers disarrangement of zinc distribution in rice plants. J. Exp. Bot. 58, 2909–2915 10.1093/jxb/erm147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishimaru Y., Suzuki M., Kobayashi T., Takahashi M., Nakanishi H., Mori S., et al. (2005). OsZIP4, a novel zinc-regulated zinc transporter in rice. J. Exp. Bot. 56, 3207–3214 10.1093/jxb/eri317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishimaru Y., Suzuki M., Tsukamoto T., Suzuki K., Nakazono M., Kobayashi T., et al. (2006). Rice plants take up iron as an Fe3+ phytosiderophore and as Fe2+. Plant J. 45, 335–346 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02624.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kärenlampi S., Schat H., Vangronsveld J., Verkleij J. A. C., van der Lelie D., Mergeay M., et al. (2000). Genetic engineering in the improvement of plants for phytoremediation of metal polluted soils. Environ. Pollut. 107, 225–231 10.1016/S0269-7491(99)00141-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korenkov V., Hirshi K., Crutchfield J. D., Wagner G. J. (2007). Enhancing tonoplast Cd/H antiport activity increases Cd, Zn, and Mn tolerance, and impacts root/shoot Cd partitioning in Nicotiana tabacum L. Planta 226, 1379–1387 10.1007/s00425-007-0577-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Dhankher O. P., Carreira L., Lee D., Chen A., Schroeder J. I., et al. (2004). Overexpression of phytochelatin synthase in Arabidopsis leads to enhanced arsenic tolerance and cadmium hypersensitivity. Plant Cell Physiol. 45, 1787–1797 10.1093/pcp/pch202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez M., Bernal P., Almela C., Vélez D., Garcia-Augustin P., Serrano R., et al. (2006). An engineered plant that accumulates higher levels of heavy metals than Thlaspi caerulescens, with yields of 100 times more biomass in mine soils. Chemosphere 64, 478–485 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2005.10.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmgren M. G., Clemens S., Williams L. E., Krämer U., Borg S., Schjorring J. K., et al. (2008). Zinc biofortification of cereals; problems and solutions. Trends Plant Sci. 13, 464–473 10.1016/j.tplants.2008.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelloux J., Rustérucci C., Mellerowicz E. J. (2007). New insights into pectin methylesterase structure and function. Trends Plant Sci 12, 267–277 10.1016/j.tplants.2007.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pianelli K., Mari S., Marquès L., Lebrun M., Czernic P. (2005). Nicotianamine over-accumulation confers resistance to nickel in Arabidopsis thaliana. Transgenic. Res. 14, 739–748 10.1007/s11248-005-7159-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilon-Smits E., Pilon M. (2002). Phytoremediation of metals using transgenic plants. Critcal Rev. Plant Sci. 21, 439–456 10.1080/0735-260291044313 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Puig S., Andrés-Colás N., García-Molina A., Peñarrubia L. (2007). Copper and iron homeostasis in Arabidopsis: responses to metal deficiencies, interactions and biotechnological applications. Plant Cell Environ. 30, 271–290 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2007.01642.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricachenevsky F. K., Menguer P. K., Sperotto R. A., Williams L. E., Fett J. P. (2013) Roles of plant metaltolerance proteins (MTP) in metal storage and potential use in biofortification strategies. Front. Plant Sci. 4:144 10.3389/fpls.2013.00144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaaf G., Honsbein A., Meda A. R., Kirschner S., Wipf D., von Wiren N. (2006). AtIREG2 encodes a tonoplast protein involved in iron-dependent nickel detoxification in Arabidopsis thaliana roots. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 25532–25540 10.1074/jbc.M601062200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seth C. S. (2012). A review on mechanisms of plant tolerance and role of transgenic plants in environmental clean-up. Bot. Rev. 78, 32–62 10.1007/s12229-011-9092-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Siemianowski O., Barabasz A., Kendziorek M., Ruszczyñska A., Bulska E., Williams L. E., et al. (2014). AtHMA4-expression in tobacco reduces Cd accumulation due to the induction of the apoplast barier. J. Exp. Bot. 65, 1125–1139 10.1093/jxb/ert471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siemianowski O., Barabasz A., Weremczuk A., Ruszczyñska A., Bulska E., Williams L. E., et al. (2013). Development of Zn-related necrosis in tobacco is enhanced by expressing AtHMA4 and depends on the apoplastic Zn levels. Plant Cell Environ. 36, 1093–1104 10.1111/pce.12041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siemianowski O., Mills R. F., Williams L. E., Antosiewicz D. M. (2011). Expression of the P1B-type ATPase AtHMA4 in tobacco modifies Zn and Cd root to shoot partitioning and metal tolerance. Plant Biotechnol. J. 9, 64–74 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2010.00531.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair S. A., Krämer U. (2012). The zinc homeostasis network of land plants. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1823, 1553–1567 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2012.05.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song W.-Y., Sohn E. J., Martinoia E., Lee Y. J., Yang Y.-Y., Jasinski M., et al. (2003). Engineering tolerance and accumulation of lead and cadmium in transgenic plants. Nat. Biotechnol. 21, 914–919 10.1038/nbt850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talke I. N., Hanikenne M., Krämer U. (2006). Zinc-dependent global transcriptional control, transcriptional deregulation, and higher gene copy number for genes in metal homeostasis of the hyperaccumulator Arabidopsis halleri. Plant Physiol. 142, 148–167 10.1104/pp.105.076232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas J. C., Davies E. C., Malick F. K., Endreszl W., Williams C. R., Abbas M., et al. (2003). Yeast methallothionein in transgenic tobacco promotes copper uptake from contaminated soils. Biotechnol. Prog. 19, 273–280 10.1021/bp025623q [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Mortel J. E., Villanueva L. A., Schat H., Schat K., Kwekkeboom J., Coughlan S., et al. (2006). Large expression difference in genes for iron and zinc homeostasis, stress response, and lignin biosynthesis distinguish roots of Arabidopsis thaliana and related metal hyperaccumulator Thlaspi caerulescens. Plant. Physiol. 142, 1127–1147 10.1104/pp.106.082073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verbruggen N., Hermans C., Schat H. (2009). Molecular mechanisms of metal hyperaccumulation in plants. New Phytol. 181, 759–776 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02748.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M., Gruissem W., Bhullar N. (2013). Nicotianamine synthase overexpression positively modulates iron homeostasis-related genes in high iron rice. Front. Plant. Sci. 4:156 10.3389/fpls.2013.00156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wirth J., Poletti S., Aeschlimann B., Yakandawala N., Drosse B., Osorio S., et al. (2009). Rice endosperm iron biofortification by targeted and synergistic action of nicotianamine synthase and ferritin. Plant Biotechnol. J. 7, 631–644 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2009.00430.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wojas S., Clemens S., Hennig J., Skłodowska A., Kopera E., Schat H., et al. (2008). Overexpression of phytochelatin synthase in tobacco: distinctive effects of AtPCS1 and CePCS genes on plant response to cadmium. J. Exp. Bot. 59, 2205–2219 10.1093/jxb/ern092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wojas S., Hennig J., Plaza S., Geisler M., Siemianowski O., Skłorodowska A., et al. (2009). Ectopic expression of Arabidopsis ABC transporter MRP7 modifies cadmium root-to-shoot transport and accumulation. Environ. Pollut. 157, 2781–2789 10.1016/j.envpol.2009.04.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong C. K. E., Cobbett C. (2009). HMA P-type ATPases are the major mechanism for root-to-shoot Cd translocation in Arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytol. 181, 71–78 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02638.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H., Chen C., Du J., Liu H., Cui Y., Zhang Y., et al. (2012). Co-overexpression FIT with AtbHLH38 or AtbHLH39 in Arabidopsis-enhanced cadmium tolerance via increased cadmium sequestration in roots and improved iron homeostasis of shoots. Plant Physiol. 158, 790–800 10.1104/pp.111.190983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]