Abstract

A computationally efficient speech enhancement pipeline in noisy environments based on a single-processor implementation is developed for utilization in bilateral cochlear implant systems. A two-channel joint objective function is defined and a closed form solution is obtained based on the weighted-Euclidean distortion measure. The computational efficiency and no need for synchronization aspects of this pipeline make it a suitable solution for real-time deployment. A speech quality measure is used to show its effectiveness in six different noisy environments as compared to a similar one-channel enhancement pipeline when using two separate processors or when using independent sequential processing.

Keywords: Bilateral cochlear implants, Single-processor speech enhancement for bilateral cochlear implants, Environment-adaptive speech enhancement

1. Introduction

Cochlear Implants (CIs) are prosthetic devices used to restore hearing sensation in profoundly deaf people. Speech understanding by CI patients has been reported to be acceptable in quiet and controlled listening conditions, but in actual noisy environments, it has been shown to decrease significantly (Remus and Collins, 2005; Fetterman and Domico, 2002). This issue has led to the development of speech enhancement algorithms to suppress noise (Loizou, 2006; Hu et al., 2007; Loizou et al., 2005). These algorithms have involved noise reduction strategies either as a preprocessing step before delivering speech to the CI speech processing pipeline or devising a noise attenuation technique as a built-in function inside the CI speech processing components (Loizou, 2006).

Because of different characteristics of different noise types, a system capable of adapting its parameters to different noisy environments was developed in our previous work (Gopalakrishna et al., 2012). This system allowed a real-time implementation of a noise suppression technique which automatically selected a set of parameters trained offline for each noisy environment. As a result, automatic noise suppression was achieved by switching among appropriate parameters via a noise classification decision in an online manner. Also, the system design was done in such a way that some of its components shared the same computations, leading to real-time throughputs (Mirzahasanloo et al., 2012).

In this work, the automatic enhancement framework in (Gopalakrishna et al., 2012) is extended to bilateral cochlear implants. The objective here is to increase the reliability of the system by taking advantage of the two (left and right) signal sources, and provide better enhancement of the noisy signals. In unilateral CIs, there is no directional information perceived by patients, so they face difficulties locating sound sources (Litovsky et al., 2004; Ching et al., 2007). Bilateral CIs provide a natural way to create a sense of directionality. There are many studies, e.g. (Kühn-Inacker et al., 2004; Litovsky et al., 2006, 2004; Van Hoesel and Tyler, 2003; Müller et al., 2002; Van Hoesel, 2004), supporting that wearing two CI devices, instead of only one, contributes to improvements in speech understanding. The main challenges addressed in this work have been how to keep speech distortions as low as possible and at the same time not let the computational complexity increase.

Bilateral CIs, utilizing multi-microphone or multichannel techniques, have been developed mainly based on adaptive beamforming algorithms (Kokkinakis and Loizou, 2010). Limited attempts have been made in the literature towards developing strategies that are amenable to real-time operation on resource limited processors. This work is an attempt to advance the CI technology toward the real-time implementation of the speech processing algorithms in bilateral systems. We have approached the problem by considering that there is only a single processor that is feeding the left and right CIs. Using two processors would require the two signals to be synchronized in real-time. In our approach, since the bilateral stimulation signals are provided by only one processor, no synchronization problem exists. In addition, the system is made more cost-effective since only a single processor is used.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. First, an overview of the existing system for unilateral CIs is provided in Section 2, where its data-driven noise estimation and suppression approaches are reviewed. Our extension of this system to the bilateral stimulation on a single-processor is then outlined in Section 3. Section 4 formulates the proposed joint optimization approach for the bilateral system and provides more details of our solution. The components of our pipeline are then presented in Section 5. Section 6 provides an analysis of the storage requirements and memory efficiency of the proposed approach. Speech quality measure and timing results are reported and discussed in Sections 7 and 8 for different noise types and across different binaural directionalities. Finally, Section 9 concludes the paper.

2. Overview of existing unilateral system

Fig. 1 illustrates a block diagram of the environment-adaptive pipeline for unilateral cochlear implant speech processing previously developed in (Gopalakrishna et al., 2012). The pipeline involves two main parallel paths for noise detection and noise suppression. A Voice Activity Detector (VAD) is used to determine signal frames containing speech. When it is purely noise, a Gaussian Mixture Model (GMM) classifier, trained on different noise classes, is used to determine the noise type. After noise detection, the corresponding optimized gain parameters are loaded to a noise suppression function to make the suppression path specific to the detected noise environment.

Fig. 1.

Block diagram representation of the previously developed unilateral cochlear implant system.

2.1. Data-driven noise tracking and speech enhancement

Statistical spectral enhancement methods can be characterized based on the following three main items (Loizou, 2007):

2.1.1. Prior SNR estimation

Decision-directed approach is the most commonly used method (Ephraim and Malah, 1984). Also, the modifications proposed in (Erkelens et al., 2007) address the bias aspect in the convergence behavior of the decision-directed rule.

Let Rk(n) and Ak(n) be the noisy and clean spectral amplitudes in the frequency bin k for the time frame n, respectively. The clean amplitude estimates Âk are then derived by applying a SNR-dependent gain function G to the noisy amplitudes as follows:

| (1) |

where ζk and ξk denote the prior and posterior SNRs which are defined as ζk = λx(k)/λd(k) and . The computation of these SNRs require estimates of the clean spectral variance λx(k) and the noise spectral variance λd(k). The decision-directed estimator uses the following rule to update the prior SNR for each time frame n

| (2) |

where α is a weight close to one (for the results reported later in the paper, α was set to 0.98), and ζmin is a lower bound on the estimated value of ζ̂k (for the results reported later in the paper, ζmin was set to −19 dB).

2.1.2. Reconstruction

Based on the estimated prior and posterior SNRs, the spectral amplitude of the enhanced signal is retrieved from the noisy input signal based on an assumed probability density function and the optimization of an objective function. The optimization solution for the reconstruction gain defined in (1) is derived either analytically or obtained using data-driven training algorithms. Two noteworthy solutions include:

-

MMSE spectral amplitude estimation (Ephraim and Malah, 1984) which provides an analytical solution for Gaussian density and optimizing the minimum mean-squared error, that is

(3) where(4) and Φ(a; b; x) denotes the confluent hypergeometric function defined as in (Abramowitz and Stegun, 1965).

-

MMSE log spectral amplitude estimation (Ephraim and Malah, 1985) which provides an analytical solution for Gaussian density and optimizing the minimum mean-squared log spectral error, that is

(5) where vk is the same as in (4).

Maximum a posteriori (MAP) amplitude estimation approaches including joint MAP estimator proposed in (Lotter and Vary, 2005).

The data-driven approach utilized is the one reported in (Erkelens et al., 2007). It uses a gain table representation over prior and posterior SNRs for the amplitude estimation. The optimal gains corresponding to this lookup table representation are then obtained by using a distortion measure defined over noisy and clean spectral data. This is further discussed in Section 3.

2.1.3. Noise estimation

In parallel to the prior SNR estimation and the amplitude reconstruction, noise statistics need to be estimated:

Stationary noise: constant variance is usually estimated in the first few silent frames of a sentence.

Non-stationary noise: The minimum statistics method (Martin, 2001) is often used for the non-stationary case (Erkelens and Heusdens, 2008).

To design the enhancement system optimized for different environments, either the noise estimation or the reconstruction needs to be parameterized based on the noise data. As will be discussed in Section 4, the gain table representation in (1) was utilized for training the reconstruction function in this work.

Our approach in (Gopalakrishna et al., 2012) as outlined in Fig. 1 incorporates a gain table representation for the noise tracking transformation and uses the log- MMSE reconstruction in (5) for the final amplitude estimation along with the environment-specific noise estimation trained and optimized for various noise environments. The main idea here is relying on the data-driven gain table for the noise tracking (Erkelens and Heusdens, 2008). The reconstruction part is independent of the environment and the same algorithm is used for all the noise types.

3. Extension to bilateral cochlear implants

The approach adopted in (Gopalakrishna et al., 2012) is that the noise suppression structure is different for each noisy environment. Then, by detecting a noise class, the system switches to the appropriate structure. Now, the approach taken here is that the environment-dependent structure is the case not only for the noise suppression but also for different directions. One realization of this extension is shown in Fig. 2 by considering the parameter space consisting of noise suppression parameters plus directional parameters. Here, gains are considered to be functions of both SNRs and source angles (directions). In other words, the gain function becomes different along different directions. Its basic enhancement part is illustrated in Fig. 3.

Fig. 2.

Block diagram representation of the extension to bilateral cochlear implant system.

Fig. 3.

Gain function based on the proposed suppression scheme.

Basically, gain G is applied only onto the first input, though it is not only a function of estimated prior SNR (ζ) and posterior SNR (ξ) but also dependent on the time delay estimation between the two inputs. This time delay estimate is the Interaural Time Difference (ITD) in binaural hearing. It is denoted by τ̂ here, as shown in Fig. 3. In addition to the third argument of the gain function, the second input is used as extra information to increase the reliability of the Voice Activity Detector (VAD) and the noise classification components. All the processing in the main pipeline including the noise suppression is performed on the first input only. Stimulation signals representing the second input is reconstructed using the directional information estimated from the ITD algorithm.

Although this approach is computationally attractive, it might be prone to non-negligible distortions. This drawback becomes more pronounced if the τ̂ estimate is not precise enough. To address this issue, the optimization of the direction-dependent gain parameters is performed with respect to the distortion measure not only for the first input but also for the reconstructed second input. In this manner, the distortion measure is defined to minimize MSE for both the inputs.

Suppose X1 and X̂1 are the clean and enhanced signals for input 1 and D(X1, X̂1) is the distortion measure used to optimize the gain parameters, then

| (6) |

where Gij denotes the gain parameter corresponding to the cell representing the ith partition of the prior SNR range and the jth partition of the posterior SNR range. If the range of prior and posterior SNR estimates are partitioned to a total of I and J values, respectively, the gain is an I × J matrix containing the noise suppression parameters, that is

| (7) |

Now assume that the following directionality distortion measure incorporating both of the inputs is minimized, that is

| (8) |

where Gijl is the gain parameter corresponding to the cell representing the ith partition of the prior SNR range and the jth partition of the posterior SNR range and the lth partition of the time delay range. Different weights could be assigned to the two distortion measures as stated in the next section. This is exhibited in Fig. 4, where Y1 and Y2 in this figure denote the original noisy inputs. Once the optimal gain parameters are stored for each noise environment, they are then used in real-time to suppress noise in the first input signal.

Fig. 4.

Optimization process of data-driven noise suppression gain.

4. Bilateral data-driven enhancement

As outlined in the previous section, noise suppression is applied to a reference signal according to the prior and posterior SNR estimates. The reference signal is defined as the input which arrives first from the right or left microphones and the other one is defined as the non-reference signal. All the associated variables are distinguished here by the subscripts r and nr, respectively. In other words, the reference signal is the first input when the delay τ̂ is positive, and it is the second one if it is negative.

After applying the suppression gain on the reference signal, an enhanced reference signal is obtained. This gain is a function of prior and posterior SNRs.

Then, the enhanced non-reference signal is obtained by applying another gain H which is a function of the time difference of the estimate of the direction of arrival,

| (9) |

This constitutes a simple representation of the Head-Related Transfer Function (HRTF) where Hl values are assumed to be only a function of delay. This function is a representation of the Interaural Level Difference (ILD). The ITD and ILD are the two main binaural cues for sound localization that are modeled in this representation. HRTF is also assumed to be the same for both left-to-right and right-to-left directions. As a result, the problem of identifying these transfer functions is transformed to the problem of estimating the time difference of arrival, thereby utilizing a data-driven approach to identify ILDs. There are many methods developed for this purpose in the literature; here we have utilized the Generalized Cross Correlation technique as it provides an appropriate compromise between accuracy and computational complexity (Chen et al., 2006).

The objective is to find all Gij and Hl parameters by optimizing a distortion measure defined based on both the reference and non-reference outputs. Having estimated the prior and posterior SNRs and the time delay in a given fame, the corresponding cells of Gij and Hl can then be determined. Because Gij’s are applied only onto the reference input, their optimal values are independent of the non-reference signal. To find optimal Gij’s via the MMSE minimization, noisy and clean data points of the reference signal need to be stored during an offline data collection process.

If Rr,ij(m) is the mth data-point of the magnitude spectrum of the noisy reference signal and Ar,ij(m) is the corresponding clean signal for which the estimated prior and posterior SNRs fall into the (i, j)th cell of the table G, this dataset is needed to be stored for the optimization of , where Mij denotes the total number of data points observed at the SNRs corresponding to (i, j). Note that m is only an index for pairs of noisy amplitude Rr,ij(m) and corresponding clean amplitude Ar,ij(m) which fall into the (i, j)th cell of G. Then, noting Mij is the number of train data points for each (i, j)th parameter of G or Gij, a total of data points need to be collected from the reference signal for training purposes.

The gain H is applied onto the enhanced reference signal to obtain the enhanced non-reference output. Therefore, the corresponding clean non-reference output spectrum is stored as , where (Rrijl(m′), Anr,ijl(m′)) denotes the m′th pair of data for the (i, j)th estimate of the SNRs and when τ̂ falls into the lth cell of the vector H, and denotes the total number of observations in the (i, j)th estimate of SNRs and lth estimate of the delay.

The total distortion is considered to be a linear combination of distortions associated with the reference and the non-reference spectral errors, that is

| (10) |

The parameter 0 ≤ β ≤ 1 corresponds to the weight assigned to the error in the non-reference signal versus the reference signal. It is a user-defined parameter which reflects the relative importance of optimization on the non-reference path versus the reference one. A weight of zero corresponds to the regular one-channel (unilateral) case (Erkelens et al., 2007) and the non-reference speech signal is left unprocessed. On the other hand, a weight of unity treats the two distortion paths equally. The unilateral case (β = 0) is shown in our previous work to outperform the fixed suppression approach in terms of a number of quality measures. With a non-zero value of β, one would deal with a more complicated gain optimization problem as it becomes a joint optimization with an objective function defined over both left and right spectra. Then, a weight of β = 1 would correspond to the most complicated form of this optimization problem. In the experiments reported in this paper, the worst case results are reported with β set to 1.

The distortions Dr and Dnr are

| (11) |

with

| (12) |

and

| (13) |

with

| (14) |

where Dr,ij and Dnr,ijl in (12) and (14) are defined based on the weighted-Euclidean distortion measure on spectral errors (Loizou, 2005; Erkelens et al., 2007) and p is a weighting parameter. A weight of p = 0 reduces the problem to the traditional MMSE optimization problem, while non-zero weights amplify the effect of smaller or larger amplitudes. For example, a weight of p = −1 gives more weight to smaller amplitudes. An analytical study of the effect of different weights on the derived gain functions and their relations to MMSE and log-MMSE solutions is provided in (Loizou, 2005). In the experiments reported in this work, the MMSE criterion (p = 0) is considered, while the derivations are stated for any weights.

Hence,

| (15) |

To find the solution for this optimization problem, let us define the following quantities:

| (16) |

| (17) |

| (18) |

| (19) |

As a result of setting the partial derivatives to zero, that is

| (20) |

| (21) |

| (22) |

| (23) |

From the above equations, it can be seen that the optimal value of each Gij and Hl depends on the knowledge of the true value of the other one. A simple approach would be to recursively update the solution by starting with an appropriate initialization. Here, Gij is initialized with the weighted-Euclidean response of the regular case (Loizou, 2005; Erkelens et al., 2007) and the problem is solved in a quasi-static way as follows:

| (24) |

Then, the solution is updated according to ((21) and (23)) at any iteration step q as follows:

| (25) |

| (26) |

This recursion is repeated until a satisfactory convergence is reached. Note that although unlike the unilateral case the optimal values of the gain parameters in (21) are not reached in a closed form, it can be simply shown that the optimization problem defined in (15) is a convex function of G and H gain parameters. Therefore, a sufficient number of recursions stated in (25) and (26) guarantees reaching the global optimum. In practice, reaching only a close estimation of the global optimal point may be satisfactory and then going through a limited number of recursions can reduce the training time. Initializing the recursion with an appropriate starting gain value is important in this regard. The closed form solution of the unilateral case would serve as a good initialization choice and is used here in (24). Obviously, as these computations are all performed offline, attempting to reach a more accurate estimate by considering more number of recursions would not have any effect on the real-time processing load of the algorithm.

5. Components of bilateral enhancement

To further clarify the entire process, the real-time pipeline of the environment-specific unilateral CI system in (Gopalakrishna et al., 2012) is outlined below. The operations written inside parentheses are added to the one-channel pipeline for the bilateral extension.

In each frame:

Estimate time delay between input 1 and input 2.)

Decompose input 1 (and input 2) using Wavelet Packet Transform.

Use wavelet coefficients to compute the subband power difference for the VAD to determine whether speech data is noise-only.

Combine the VAD outputs from both decompositions to make the final decision on noise-only detection.)

If noise is detected by the VAD, extract features using the wavelet coefficients of the decomposition 1 (and decomposition 2).

Classify the noise using features extracted for the input 1 (and input 2) or (combine classification results using features of input 1 with those of input 2).

If change in the noise class is detected, load the gain function optimized for the corresponding noise environment (and the estimated direction).

Estimate prior and posterior SNRs.

Apply appropriate gains to the input 1 frequency bands.

Extract envelope, select max amplitude channels, compress, and pulse modulate.

Reconstruct input 2 stimulation signal based on input 1 stimulation signal using the estimated time delay.)

With the gain function receiving three inputs of SNRs and direction, the requirement remains manageable in storage requirements. It should be noted that the optimization solution for the noise environment is challenging even for a simple distortion. Therefore, here it is considered that the gain on the first input is dependent on SNR estimations, and the second input is dependent on the direction estimation. This is based on the assumption that SNR-dependent and direction-dependent gains are independent. However, still the gain optimization is performed based on the joint distortion of the sources.

Let the reference signal be the input that is recognized based on our estimation of the time difference of arrival. Then, the SNR-dependent gains are applied onto the reference signal and the non-reference enhanced signal is reconstructed by using the direction-dependent gains applied onto the enhanced version of the reference signal. For each noise type, tuning of the gains is performed based on an extension of the data-driven approach in (Erkelens and Heusdens, 2008; Ephraim and Malah, 1984). It uses the decision-directed approach in (Ephraim and Malah, 1984) to estimate the prior SNR and the IMCRA method (Cohen, 2003) to estimate noise.

After collecting appropriate training data corresponding to the recognized grid cell, they are used in the MSE optimization of the gain parameters. Note that here we have only stated the solution for the weighted Euclidean distortion measure for the two signals with the weighting parameter p as defined in (12) and (14). After learning the gain parameters for each environment, real-time automatic suppression can be performed according to the model considered in the above offline gain optimization procedure.

6. Memory requirements

Running the proposed enhancement method requires storing a suppression gain function G and an HRTF table H for each environment. In this section, the storage requirement is discussed. If the bilateral enhancement was performed using two independent processors in parallel or by a single processor but in a sequential manner, it would require storing two suppression gain functions for each noise type. This would be equal to 2 × I × J number of parameters. Note that this way, synchronization would be required and two processors would be performing the bilateral stimulation. To avoid the synchronization problem while providing the bilateral stimulation using only a single processor, one needs to store L independent suppression gain tables for each direction of a noise type. This would require a storage capacity of L × I × J number of gain parameters. Using our proposed method, this storage is reduced to storing a suppression gain table and an HRTF vector according to the number of directions. This means that the storage is reduced to only (I × J + L) number of gain parameters. Based on a word length of W bits for each gain parameter, Table 1 shows the memory requirements for each method of the bilateral enhancement. Typical memory requirements for a 60 × 70 representation of the suppression gain table, considering 13 different directions, using a word length of 16 bits are also listed. It can be seen that our proposed method for the bilateral enhancement requires only 8.2285 kB of storage which is only 0.3% more than what is required for storing one suppression gain table for the unilateral enhancement (16.4063/2 = 8.2032 kB).

Table 1.

Storage requirements of different bilateral enhancement methods and typical needed memory for a 60 × 70 suppression gain table, an HRTF of length 13 directions, and a word length of 16 bits.

| Hardware system architecture | Double-processor/single-processor (sequential processing) | Single-processor (independent gains for different directions) | Single-processor (proposed) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Storage requirements (bits) | 2 × I × J × W | L × I × J × W | (I × J + L) × W |

| Typical memory (kB) | ≈16.4 | ≈106.6 | ≈8.2 |

7. Experimental setup

Speech enhancement quality and timing performance of the discussed extension were assessed using six commonly encountered noise types. Noise samples for training were collected using the same BTE (Behind-The-Ear) microphone worn by Nucleus ESPrit implant users. For each environment, a total of five sample files of one minute duration were collected. In every recording, we also data-logged the integrated (average) sound pressure levels (SPLs) for the run periods of one minute, almost exactly while the BTE recordings were on. The average SPLs were 75.8 dBA for Street, 66.4 dBA for Car, 60.4 dBA for Restaurant, 67.8 dBA for Mall, 81.7 dBA for Bus, and 74.6 dBA for Train noise.

To simulate bilateral hearing conditions, speech sentences were convolved with a patient-specific HRTF. Training of the suppression functions along with the HRTF gain parameters were performed using the first 50 clean speech sentences from the IEEE Corpus database (Subcommittee, 1969). All suppression and HRTF gain parameters associated with each environment were trained by adding the recorded noise samples to the IEEE sentences as clean speech signals. The resulting noisy files were then used to generate the required training set.

The CIPIC HRTF database (Algazi et al., 2001) was utilized to generate the reference and non-reference signals associated with the clean, noise and noisy data. It was considered that both the clean and noise signals passed through a left and a right HRTF before being delivered to the CI speech enhancement pipeline. The subject number 3 of the CIPIC database is reported here. The elevation angle was assumed to be zero, but different azimuth angles ranging from −80° to 80° with this discretization [−80, −65, −55, −45:5:45, 55, 65, 80] were considered for a total of 25 different Head-Related Impulse Responses (HRIRs). We used half of the data covering −80° to 0° (a total of 13 HRIRs); for the other half the only difference was switching the reference signal with the non-reference signal. We parameterized our estimation of the HRTF gains in seven different ITD values, distributed uniformly. Each τ̂ estimate was assigned to its closest HRTF parameter point. These impulse responses were downsampled to the clean signal sampling frequency. They were then convolved with the clean, noise and noisy signals to simulate pairs of reference and non-reference signals. Although only a portion of the entire spherical space around the head was examined here, other elevation or azimuth angles can be simply evaluated in a similar way to generate corresponding parameters. For higher resolution elevation and azimuth angles for which we did not have the HRIRs, a simple linear interpolation technique was used to estimate the enhancement output in the missing points based on their neighboring HRIRs.

The performance of the gains resulted from our joint optimization approach is compared against using the direct one-channel gain optimization applied independently on each of the reference and the non-reference signals. The weighted Euclidean distortion measure was used for a fair comparison. A total of three out of five noise files for each environment and the first 50 IEEE sentences were used to generate the training data. Two different gain tables were obtained using the reference data for the left ear and using the non-reference data for the right ear. The combination of the same reference and non-reference data was used in our two-channel enhancement involving a single-processor to obtain a suppression gain and an HRTF function for 13 different azimuth angles of the six different noise types. It was always assumed that the left ear was ipsilateral to the sound source, hence receiving the reference signal.

Noting that the delay estimation itself could produce errors in each frame, we used a median filter across the past 20 delay estimations to filter out outlier estimates. For the real-time operation of the system, this helps to prevent clicks in the outputs when the direction between the ears and the source changes. By using the median filter, a smoother transition for the change of direction over time was obtained.

Although subjective listening tests provide accurate quality evaluation measures, they are time consuming, costly and require trained listeners (Hu and Loizou, 2007, 2011). Fortunately, there are many objective evaluation methods (Quackenbush et al., 1988) attempting to predict the subjective quality of processed speech. Perceptual Evaluation of Speech Quality (PESQ), an ITU-T recommended standardized objective quality measure (ITU, 2000), is a widely used measure for this purpose. Hence, we used it here for evaluation purposes.

It is worth noting that our joint enhancement approach performs the noise estimation and a priori SNR estimation only on the reference signal, but the non-reference counterpart is reconstructed based on the direction or ITDs, and thus this is a more efficient computation than processing the two signals.

8. Results and discussion

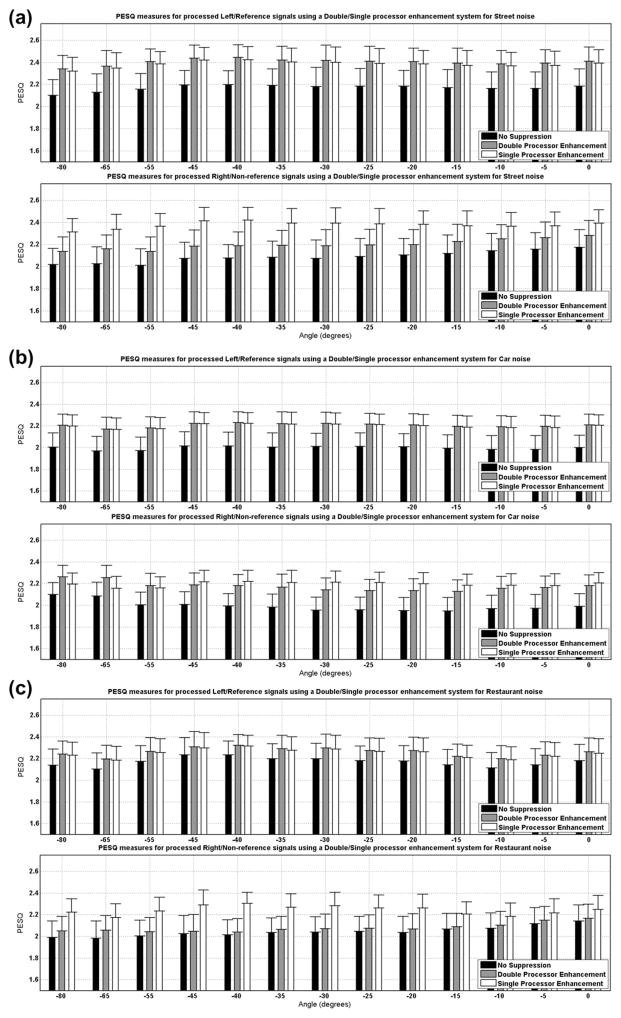

Fig. 5(a)–(f) show the comparison of the PESQ measure evaluating our joint enhancement gain parameters using single-processor bilateral processing against those involving one-channel enhancement gains using double-processor bilateral processing of the reference and non-reference signals independently for the six different noise types across 13 azimuth angles ranging from −80° to 0°. The PESQ scores on the non-processed noisy signals are shown to serve as the baseline. The results shown denote averages on the second half of the 50 IEEE sentences which had not been considered in the training phase. Also, the other two noise files of each environment not used in the training were used to generate noisy signals. It can be observed that for the reference signal which was obtained directly by applying the suppression gain table, there was not a significant performance loss when using our joint enhancement method. However, a higher quality was achieved for the non-reference signal which was obtained by applying the HRTF estimates onto the reference counterpart according to the binaural reconstruction based on the time delay estimation (see Fig. 4). From this figure, it can be seen that not only one gets the binaural stimulation capability, but also some correction of errors given by the single suppression gain table. In other words, one obtains the non-reference processed signal with a slightly higher PESQ scores than the single optimization of the suppression gain.

Fig. 5.

Quality assessments are performed based on PESQ scores, comparison with no-suppression scores as baseline in six noisy environments of (a) Street, (b) Car, (c) Restaurant, (d) Mall, (e) Bus and (f) Train noise. The double-processor enhancement system processes the left and right signals independently in parallel, each using one of the two available processors. The suppression gain tables used for the left and right signals were optimized by training over their associated left or right collected data along each direction. The same datasets were used for training our proposed single-processor enhancement and HRTF gain tables. The left signal was considered to be the reference input in this set of experiments.

A statistical significance analysis using the standard t-test was carried out revealing that in all 78 cases involving six noise types and 13 directions, it always failed to reject the null hypothesis between double-processor and single-processor PESQ scores on the reference signal. The averages of the p-values over different directions were 0.44, 0.76, 0.89, 0.96, 0.67 and 0.83 for the noisy environments of Street, Car, Restaurant, Mall, Bus and Train, respectively, indicating non-significant differences. On the other hand, the same statistical test on the associated non-reference PESQ scores showed significant improvement of single-processor results over double-processor ones in 70 out of 78 cases at the 95% confidence level and in 65 cases at the 99% confidence level.

As shown in Table 2, the CPU processing time was significantly decreased by using our single-processor enhancement pipeline (the timing measurements were obtained on a PC platform with a CPU of 2.66 GHz clock rate. Also, note that the numbers denote average timings for processing the IEEE sentences which are approximately 2–3 s long). It can be noticed that the independent processing via using two processors running in parallel is only 11% faster than using only a single processor. Furthermore, the proposed single-processor approach is about 44% faster than using a single processor with a sequential processing of the two signals. Thus, it is more suitable for real-time implementation than a sequential processing of both the left and right signals for bilateral stimulation. It is also worth emphasizing that in our approach there would be no need to be concerned about any synchronization to coordinate the operation of the two signal processing paths.

Table 2.

Average timing outcome over all noise types and all azimuth angles (in seconds on speech files with length of 2–3 s) by a single processor (proposed) compared to sequential independent processing of the left and right signals using a single processor and a double-processor system (two separate processors) without any synchronization.

| Hardware system architecture/direction | Left | Right |

|---|---|---|

| Double-processor | 0.2741 | 0.2735 |

| Single-processor (sequential processing) | 0.5476 | |

| Single-processor (proposed) | 0.3081 | |

We have considered six commonly encountered noise types and trained the gain tables for each environment independently. When the ambient noise type is not one of these six trained environments, the classifier assigns it to the closest class among the trained noise types and the associated suppression gain table is loaded to the enhancement component. To assess the performance when a noise type other than those considered for training is encountered, an unknown noise (Flight noise) was added to the clean speech files, but the trained gain tables were used for the enhancement. Fig. 6 shows the average PESQ measures for the left and right processed signals when each of the six trained gain tables was used for the enhancement. It can be observed that the measures were still improved but not as much as when the specific gain tables were used for each specific noise type. This experiment demonstrates how unseen noise types are dealt with. It should be emphasized that the measures in Fig. 6 correspond to the averaged outcome over all the trained gain tables. However, in general, better results are obtained as the gain for the noise type with the highest similarity to the unknown noise is loaded into the enhancement function.

Fig. 6.

PESQ quality measure comparisons when an unknown noise is encountered. The scores are the average of the right and left quality measures when each of the other six trained gain tables is used for the enhancement.

In summary, the introduced pipeline is computationally more efficient than independently processing two signals for bilateral stimulation while it does not cause any statistically significant performance loss in terms of speech quality. Meanwhile, it is still environment-adaptive and amenable to real-time implementation. These characteristics make this pipeline a suitable choice for deployment in bilateral CIs. It is worth mentioning that the above framework is data-driven and is not based on a closed form analytical solution. If nonlinear optimization techniques are used, various distortion measures can be considered. Also, it should be noted that putting both suppression and HRTF gain functions in the data-driven optimization enables some modeling and estimation errors in the suppression gain to be corrected by the HRTF parameters. Finally, note that we have not considered a simple extension of the previous one-channel enhancement to include directionality, rather reached a computationally tractable framework by not considering different suppression gains for different directions, but by training the HRTF parameters directly. This makes the obtained optimized parameters reusable for other speech processing tasks.

9. Conclusion

A single-processor enhancement approach has been introduced in this paper for deployment in bilateral cochlear implant systems. Because the optimization of suppression and binaural reconstruction gain parameters is done in a data-driven manner, it has been shown that it can be tuned to different noise types with different characteristics. The PESQ quality assessment measure in six different commonly encountered noisy environments showed that the performance loss is statistically not significant compared to the independent processing of the left and right signals. The proposed pipeline has been demonstrated to be suitable for real-time deployment because of its computational and storage efficiency.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Grant No. DC010494 from NIH/NIDCD.

Footnotes

This paper is dedicated to the memory of Dr. Philipos Loizou who lost his battle against cancer and passed away in July 2012.

References

- Abramowitz M, Stegun IA, editors. Handbook of Mathematical Functions. Ninth Dover Printing; Dover, New York: 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Algazi VR, Duda RO, Thompson DM, Avendano C. The CIPIC HRTF database. Paper presented at the IEEE ASSP Workshop on Applications of Signal Processing to Audio and Acoustics; 2001. pp. 99–102. [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Benesty J, Huang Y. Time delay estimation in room acoustic environments: An overview. EURASIP J Appl Signal Process. 2006;26:19. [Google Scholar]

- Ching TYC, Van Wanrooy E, Dillon H. Binaural-bimodal fitting or bilateral implantation for managing severe to profound deafness: A review. Trends Amplif. 2007;11:161–192. doi: 10.1177/1084713807304357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen I. Noise spectrum estimation in adverse environments: Improved minima controlled recursive averaging. IEEE Trans Speech Audio Process. 2003;11:466–475. [Google Scholar]

- Ephraim Y, Malah D. Speech enhancement using a minimum mean-square error short-time spectral amplitude estimator. IEEE Trans Acoust Speech Signal Process. 1984;32:1109–1121. [Google Scholar]

- Ephraim Y, Malah D. Speech enhancement using a minimum mean-square error-log-spectral amplitude estimator. IEEE Trans Acoust Speech Signal Process. 1985;33:443–445. [Google Scholar]

- Erkelens JS, Heusdens R. Tracking of nonstationary noise based on data-driven recursive noise power estimation. IEEE Trans Audio, Speech Lang Process. 2008;16:1112–1123. [Google Scholar]

- Erkelens J, Jensen J, Heusdens R. A data-driven approach to optimizing spectral speech enhancement methods for various error criteria. Speech Comm. 2007;49:530–541. [Google Scholar]

- Fetterman B, Domico E. Speech recognition in background noise of cochlear implant patients. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;126:257–263. doi: 10.1067/mhn.2002.123044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gopalakrishna V, Kehtarnavaz N, Mirzahasanloo TS, Loizou PC. Real-time automatic tuning of noise suppression algorithms for cochlear implant applications. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2012;59:1691–1700. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2012.2191968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y, Loizou PC. Subjective comparison and evaluation of speech enhancement algorithms. Speech Comm. 2007;49:588–601. doi: 10.1016/j.specom.2006.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y, Loizou P, Li N, Kasturi K. Use of a sigmoidal-shaped function for noise attenuation in cochlear implants. J Acoust Soc Amer. 2007;128:128–134. doi: 10.1121/1.2772401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ITU, Perceptual evaluation of speech quality (PESQ), and objective method for end-to-end speech quality assessment of narrowband telephone networks and speech codecs, ITU, ITU-T rec. 2000. p. 862. [Google Scholar]

- Kokkinakis K, Loizou PC. Multi-microphone adaptive noise reduction strategies for coordinated stimulation in bilateral cochlear implant devices. J Acoust Soc Amer. 2010;127:3136–3144. doi: 10.1121/1.3372727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kühn-Inacker H, et al. Bilateral cochlear implants: A way to optimize auditory perception abilities in deaf children? Internat J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2004;68:1257–1266. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2004.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litovsky RY, et al. Bilateral cochlear implants in adults and children. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130:648–655. doi: 10.1001/archotol.130.5.648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litovsky RY, Johnstone PM, Godar SP. Benefits of bilateral cochlear implants and/or hearing aids in children. Internat J Audiol. 2006;45:S78–S91. doi: 10.1080/14992020600782956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loizou P. Speech enhancement based on perceptually motivated Bayesian estimators of the magnitude spectrum. IEEE Trans Speech Audio Process. 2005;13:857–869. [Google Scholar]

- Loizou PC. Speech processing in vocoder-centric cochlear implants. Adv Otorhinolaryngol. 2006;64:109–143. doi: 10.1159/000094648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loizou P. Speech Enhancement: Theory and Practice. CRC Press LLC; Boca Raton, Florida: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Loizou PC. Speech quality assessment. Stud Comput Intell. 2011;346:623–654. [Google Scholar]

- Loizou P, Lobo A, Hu Y. Subspace algorithms for noise reduction in cochlear implants. J Acoust Soc Amer. 2005;118:2791–2793. doi: 10.1121/1.2065847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lotter T, Vary P. Speech enhancement by MAP spectral amplitude estimation using a super-Gaussian speech model. EURASIP J Appl Signal Process. 2005;2005:1110–1126. [Google Scholar]

- Martin R. Noise power spectral density estimation based on optimal smoothing and minimum statistics. IEEE Trans Speech Audio Process. 2001;9:504–512. [Google Scholar]

- Mirzahasanloo TS, Gopalakrishna V, Kehtarnavaz N, Loizou PC. Adding real-time noise suppression capability to the cochlear implant PDA research platform. IEEE Internat Conf Eng Med Biol. 2012;2012:2271–2274. doi: 10.1109/EMBC.2012.6346415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller J, Schon F, Helms J. Speech understanding in quiet and noise in bilateral users of the MED-EL COMBI 40/40+ cochlear implant system. Ear Hear. 2002;23:198–206. doi: 10.1097/00003446-200206000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quackenbush S, Barnwell T, Clements M. Objective Measures of Speech Quality. 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Remus J, Collins L. The effects of noise on speech recognition in cochlear implant subjects: predictions and analysis using acoustic models. EURASIP J Appl Signal Process: Special Issue on DSP in Hearing Aids and Cochlear Implants. 2005;18:2979–2990. [Google Scholar]

- IEEE Subcommittee. IEEE recommended practice for speech quality measurements. IEEE Trans Audio Electroacoust. 1969;AU-17:225–246. [Google Scholar]

- Van Hoesel RJM. Exploring the benefits of bilateral cochlear implants. Audiol Neurootol. 2004;9:234–246. doi: 10.1159/000078393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Hoesel RJM, Tyler RS. Speech perception, localization, and lateralization with bilateral cochlear implants. J Acoust Soc Amer. 2003;113:1617–1630. doi: 10.1121/1.1539520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]