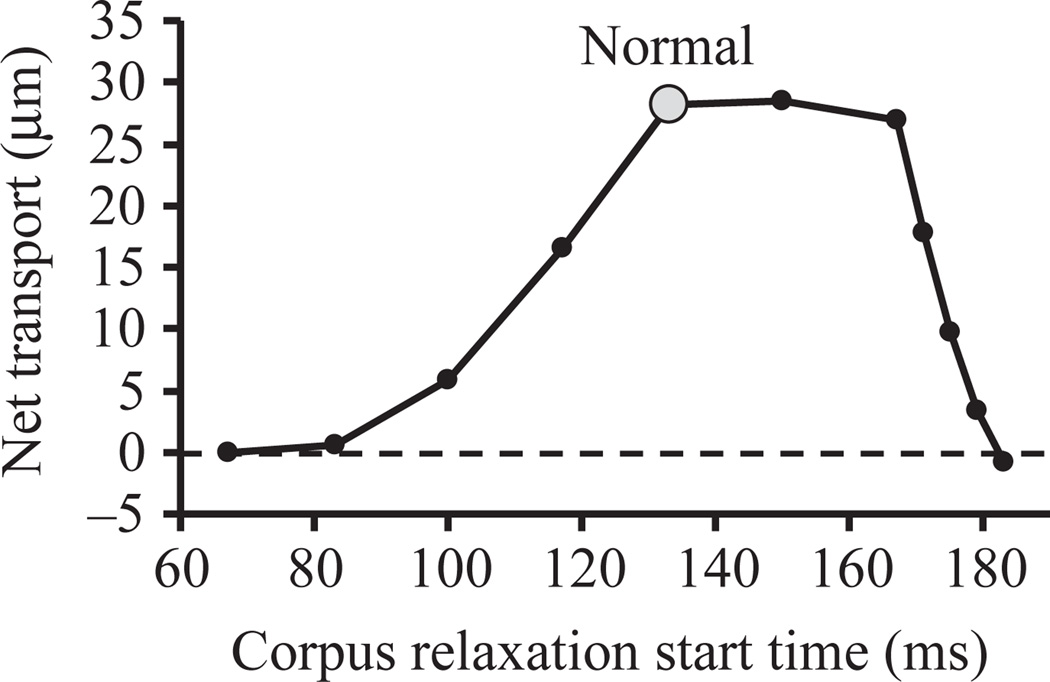

Fig. 11.

Relaxation timing affects transport. Summary of a series of simulations in which the timing of corpus relaxation was varied from the base values in Fig. 5 while isthmus motions were held constant, and the transport of a particle placed at the mouth at time zero moving at center fluid velocity was measured. (Negative net transport means that a particle placed within the corpus at time zero was transported anteriorly that distance toward the mouth.) The point labeled ‘normal’ corresponds to the movement in Fig. 5 and to the blue particle in Fig. 9. For earlier than normal relaxation time, the corpus contracted linearly from time zero to the time plotted on the x axis. For later than normal relaxation time, the corpus contracted linearly from 0 to 133 ms, remained contracted until the time plotted, then relaxed. (We also did a series of simulations in which the corpus contracted linearly from time zero to the beginning of relaxation with no pause in the fully contracted state. The results are similar except that the steep fall-off in transport begins at 167 ms instead of 171 ms and is more severe.) Relaxation always took 1/60 s. In this series, anterior isthmus contraction always began at 150 ms. This graph can however be used to predict the results of simulations in which isthmus contraction began at other times by scaling the x-axis. For instance, if corpus relaxation began at 120 ms and isthmus relaxation began at 180 ms, net transport would be the same as if corpus relaxation began at 100 ms and isthmus relaxation at 150 ms (5.9 µm from the graph), since (120, 180) can be obtained by multiplying (100, 150) by 1.2. For this statement to be exactly true, all other times, e.g. the time at which mid-isthmus relaxation begins, would also have to be multiplied by 1.2.