ABSTRACT

Nonstructural protein 3A of foot-and-mouth disease virus (FMDV) is a partially conserved protein of 153 amino acids in most FMDVs examined to date. The role of 3A in virus growth and virulence within the natural host is not well understood. Using a yeast two-hybrid approach, we identified cellular protein DCTN3 as a specific host binding partner for 3A. DCTN3 is a subunit of the dynactin complex, a cofactor for dynein, a motor protein. The dynactin-dynein duplex has been implicated in several subcellular functions involving intracellular organelle transport. The 3A-DCTN3 interaction identified by the yeast two-hybrid approach was further confirmed in mammalian cells. Overexpression of DCTN3 or proteins known to disrupt dynein, p150/Glued and 50/dynamitin, resulted in decreased FMDV replication in infected cells. We mapped the critical amino acid residues in the 3A protein that mediate the protein interaction with DCTN3 by mutational analysis and, based on that information, we developed a mutant harboring the same mutations in O1 Campos FMDV (O1C3A-PLDGv). Although O1C3A-PLDGv FMDV and its parental virus (O1Cv) grew equally well in LFBK-αvβ6, O1C3A-PLDGv virus exhibited a decreased ability to replicate in primary bovine cell cultures. Importantly, O1C3A-PLDGv virus exhibited a delayed disease in cattle compared to the virulent parental O1Campus (O1Cv). Virus isolated from lesions of animals inoculated with O1C3A-PLDGv virus contained amino acid substitutions in the area of 3A mediating binding to DCTN3. Importantly, 3A protein harboring similar amino acid substitutions regained interaction with DCTN3, supporting the hypothesis that DCTN3 interaction likely contributes to virulence in cattle.

IMPORTANCE The objective of this study was to understand the possible role of a FMD virus protein 3A, in causing disease in cattle. We have found that the cellular protein, DCTN3, is a specific binding partner for 3A. It was shown that manipulation of DCTN3 has a profound effect in virus replication. We developed a FMDV mutant virus that could not bind DCTN3. This mutant virus exhibited a delayed disease in cattle compared to the parental strain highlighting the role of the 3A-DCTN3 interaction in virulence in cattle. Interestingly, virus isolated from lesions of animals inoculated with mutant virus contained mutations in the area of 3A that allowed binding to DCTN3. This highlights the importance of the 3A-DCTN3 interaction in FMD virus virulence and provides possible mechanisms of virus attenuation for the development of improved FMD vaccines.

INTRODUCTION

Foot-and-mouth disease (FMD) is an infectious viral disease that affects cloven-hoofed animals, including cattle, sheep, swine, goats, camelids and deer. Its wide host range and rapid spread make FMD an international animal health concern, since all countries are vulnerable to accidental or intentional trans-boundary introduction (1, 2). The disease is caused by foot-and-mouth disease virus (FMDV), an Aphthovirus within the viral family Picornaviridae that exists as seven immunologically distinct serotypes: O, A, C, Asia 1, and South African Territories type 1 (SAT1), SAT2, and SAT3. The viral genome consists of a single-stranded, positive-sense RNA of about 8,200 nucleotides. The open reading frame encodes a single polyprotein that is posttranslationally processed by virus-encoded proteases into four structural proteins (VP1 through VP4) and eight nonstructural proteins (L, 2A, 2B, 2C, 3A, 3B, 3C, and 3D) (3). Although the contribution of each of these proteins to virulence during infection of the natural host is not clear, the role of nonstructural protein 3A in virulence has been the focus of several studies (4–6).

FMDV 3A is a partially conserved protein of 153 amino acids (4). The first half of the 3A coding region, which encodes an N-terminal hydrophilic domain and a hydrophobic domain capable of binding membranes, is highly conserved among all FMDVs (4). Changes in 3A have been associated with altered host range in the hepatoviruses, rhinoviruses, and enteroviruses (7). In FMDV, a deletion in the C-terminal half of 3A has been associated with decreased virulence in cattle. Thus, FMDV strains that were attenuated through serial passages in chicken embryos had reduced virulence in cattle and contained 19- to 20-codon deletions in the 3A coding region (8). A similar deletion, consisting of 10 amino acids, was also observed (9) in the FMDV isolate responsible for an outbreak of FMD in Taiwan in 1997 (O/TAW/97) that severely affected swine but did not spread to cattle (10, 11). This association between the presence of a specific deletion in this particular area of 3A and attenuation of virus virulence in cattle was recently confirmed using a recombinant O1 Campos virus harboring a 20-amino-acid deletion (12). The likely role for 3A in virulence and host range suggests that interactions with host factors underlie 3A's variability and the diversifying selection predicted to act upon it.

To better understand the role of FMDV 3A in virus replication and virulence, we attempted to identify host cell proteins that interact with 3A utilizing a yeast two-hybrid approach. Using a similar approach, we previously reported that FMDV 2C was able to bind cellular Beclin1 and vimentin facilitating virus replication (13). Here, we report that FMDV nonstructural protein 3A binds to DCTN3 (dynactin 3), a subunit of the dynactin complex that acts as a cofactor for the microtubule-base motor dynein. The screen identified a host protein, DCTN3, as a binding partner for 3A of FMDV strains O1 Campos and A24 Cruzeiro. DCTN3 is a subunit of the dynactin complex which is a cofactor for the microtubule-based motor dynein. The dynactin-dynein duplex has been implicated in several important subcellular functions involving intracellular organelle transport (14). The 3A-DCTN3 interaction initially identified by the yeast two-hybrid approach was further confirmed by deconvolution microscopy. Overexpression of DCTN3 or two proteins known to disrupt the intra- and intersubunit contacts of dynactin, p150/Glued and 50/dynamitin, induced decreased FMDV replication within infected cells. The critical amino acid residues in 3A that mediate the interaction with DCTN3 were mapped and a mutant O1 Campos FMDV (O1C3A-PLDGv) harboring substitutions in 3A altering the area critical for the interaction with DCTN3 exhibited a significant decreased ability to replicate in primary bovine cell cultures compared to its parental virus. Importantly, a significantly delayed disease was observed in cattle inoculated with O1C3A-PLDGv compared to disease produced by the virulent parental virus (O1Cv). Virus isolated from lesions of animals inoculated with O1C3A-PLDGv contained amino acid substitutions in the area of 3A mediating binding to DCTN3. FMDV 3A proteins harboring similar amino acid substitutions at critical positions were shown to react with DCTN3, supporting the possibility that interaction between DCTN3 and 3A may contribute to virulence in cattle.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines, viruses and plasmids and reagents.

Human mammary gland epithelial cells (MCF-10A) were obtained from ATCC (catalog no. CRL-10317) and maintained in a mixture of Dulbecco minimal essential medium (DMEM; Life Technologies) and F-12 Ham medium (1:1; Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) containing 5% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA), 20 ng of epidermal growth factor (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO)/ml, 100 ng of cholera toxin (Sigma-Aldrich)/ml, 10 μg of insulin (Sigma-Aldrich)/ml, and 500 ng of hydrocortisone (Sigma-Aldrich)/ml. The baby hamster kidney cell line (BHK-21; ATCC catalog no. CCL-10) was used as previously described (15). A derivative cell line obtained from bovine kidney, LFBK (16), expressing the bovine αVβ6 integrin (LFBK-αVβ6) (17) and primary cell cultures of fetal bovine kidney cells (FBK) were grown and maintained in DMEM containing 10% fetal calf serum. Growth kinetics and plaque assays were performed as described previously (18). The FMDV strain O1Campos/Bra/58 was obtained from the Institute of Virology at the National Agricultural Technology Institute, Argentina (15).

For viral replication studies, cells were plated at a density of 106 per well in a six-well plate (Falcon; Becton Dickinson Labware, Franklin Lakes, NJ). The indicated plasmids were transfected into cells using FuGene (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN) according to the manufacturer's protocol. After 24 h, the cells were infected with FMDV type O1Cv at the specified multiplicity of infection (MOI) or mock infected. Virus was allowed to adsorb for 1 h, followed by an acid wash, and then fresh medium was added containing 0.5% serum. Samples were taken at the indicated time points.

Monoclonal antibody (MAb) 2C2, directed against the FMDV type O1 nonstructural protein 3A, was developed at the Istituto Zooprofilattico Sperimentale della Lombardia e dell Emilia-Romagna, Brescia, Italy. Rabbit antibodies to DCTN3 GTX115607 (Genetex, Irvine, CA) were used to detect DCTN3. The pmEGFP-C1-CC1 and pmEGF-N1-p50 plasmids were generously donated by Martin Engelke and Bettina Cardel (University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland) and are previously described (19). Plasmid phrGFP II-N mammalian expression vector is commercially available (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). The DCTN3 overexpression plasmid utilizes a cytomegalovirus promoter that overexpresses DCTN3 (Origene, Rockville, MD; catalog no. SC110251).

Infection and transfection of cells for deconvolution microscopy.

Subconfluent monolayers of MCF-10A cells were grown on 12-mm glass coverslips in 24-well tissue culture dishes and transfected with the indicated plasmids. After 24 h, they were infected with FMDV O1Cv at an MOI of 10 50% tissue culture infective dose(s) (TCID50)/cell in MEM containing 0.5% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, 25 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), and 1% antibiotics. After the 1-h adsorption period, the supernatant was removed, and the cells rinsed with ice-cold 2-morpholinoethanesulfonic acid (MES) buffered saline (25 mM MES [pH 5.5], 145 mM NaCl) to remove unabsorbed virus. The cells were washed once with medium before fresh medium was added and then incubated at 37°C. At the indicated time points after infection, the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (EMS, Hatfield, PA) and analyzed by deconvolution microscopy. To express green fluorescent protein (GFP)-BCL2, Beclin1-FLAG, or GFP, monolayers of MCF-10A cells were transfected with 0.5 μg of plasmid DNA using FuGene (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. At 19 to 24 h posttransfection, the cells were infected as described above and then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (EMS) at the appropriate times.

After fixation, the paraformaldehyde was removed, and the cells were permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 for 5 min at room temperature (RT) and then incubated in blocking buffer (phosphate-buffered saline [PBS], 5% normal goat serum, 2% bovine serum albumin, 10 mM glycine, 0.01% thimerosa) for 1 h at room temperature. The fixed cells were then incubated with the primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. When double labeling was performed, the cells were incubated with both antibodies together. After being washed three times with PBS, the cells were incubated with the appropriate secondary antibody, goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG; 1/400; Alexa Fluor 594 or Alexa Flour 647; Molecular Probes) or goat anti-mouse isotype-specific IgG (1/400; Alexa Fluor 488 or Alexa Fluor 594; Molecular Probes), for 1 h at room temperature. After this incubation, the coverslips were washed three times with PBS, counterstained with the nuclear stain TOPRO-iodide 642/661 (Molecular Probes) or DAPI (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) for 5 min at room temperature, washed as before, mounted, and examined using a Nikon Eclipse 90i deconvolution microscope. The data were collected utilizing appropriate prepared controls lacking the primary antibodies, as well as using anti-FMDV antibodies in uninfected cells to give the negative background levels and to determine channel crossover settings. The captured images were adjusted for contrast and brightness using Adobe Photoshop software.

Development of the cDNA library.

A bovine cDNA expression library was constructed (Clontech, Mountain View, CA) using tissues susceptible to FMDV infection (dorsal soft palate, interdigital skin, middle tongue epithelium, and middle anterior lung) from healthy FMDV-free bovine. Total RNA was extracted using an RNeasy extraction kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Contaminant genomic DNA was removed by DNase treatment using Turbo DNA-free (Ambion, Austin, TX). After DNase treatment, genomic DNA contamination of RNA stocks was assessed by real-time PCR amplification targeting the bovine β-actin gene. RNA quality was assessed using RNA nanochips on an Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100. Cellular proteins were expressed as GAL4-AD fusion proteins, while FMDV 3A was expressed as a GAL 4-BD fusion protein.

Library screening.

The GAL4-based yeast two-hybrid system provides a transcriptional assay for detection of protein-protein interactions (20, 21). The bait protein, FMDV strain O1C 3A, was expressed with an N-terminus fusion to the GAL4 binding domain (BD). Full-length 3A protein (amino acids 1426 to 1578 of the FMDV polyprotein) was used for screening and for full-length mutant protein construction. As prey, the previously described bovine cDNA library containing proteins fused to the GAL4-AD were used. The reporter genes used here are histidine and adenine for growth selection. The bovine library used contains >3 × 106 independent cDNA clones. To screen, yeast strain AH109 (Clontech, Mountain View, CA) carrying 3A protein was transformed with library plasmid DNA and selected on plates lacking tryptophan, leucine, histidine, and adenine. Tryptophan and leucine are used for plasmid selection, and histidine and adenine are used for identification of positive interacting library fusions. Once identified the positive library plasmids were recovered in Escherichia coli and sequenced to identify the cellular interacting protein. Sequence analysis also determined whether the library proteins (cellular) were in frame with the activation domain. To eliminate false-positive interactions, all library-activation domain fusion proteins were retransformed into strains carrying the 3A-binding domain fusion protein, as well as into strains carrying lam-binding domain fusion. Lam is human lamin C, commonly used as a negative control in the yeast two-hybrid system as Lamin C does not form complexes or interact with most other proteins. DCTN3-AD plasmid contains the DCTN3 gene (NCBI reference sequence NM_001075660.1) fused on its amino terminus to a GAL4 activation domain.

Mammalian two-hybrid.

A mammalian Matchmaker assay kit (Clontech) was used according to the manufacturer's instructions. The plasmids used for the present study were pM-3A in which 3A was inserted into pM GAL4 DNA-BD cloning vector (Clontech) for an in-frame fusion with the Gal4 BD. pVP16-DCTN3 was inserted into the pVP16 AD cloning vector for an in-frame fusion with the GAL4 AD. As negative controls, the plasmids that were included in the Matchmaker kit—pVP16-CP that expresses a viral coat protein and pM-53 that expresses the mouse p53 protein—were used. The cells were harvested 48 h after transfection and analyzed for chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) gene expression using a CAT enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Roche, Pleasanton, CA) and performed according to the manufacturer's recommended instructions.

Site-directed mutagenesis.

Full-length pO1C (15) or 3A-BD was used as a template in which amino acids were substituted with alanine, introduced by site-directed mutagenesis using a QuikChange XL site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, Cedar Creek, TX) performed according to the manufacturer's instruction where the full-length plasmid was amplified by PCR, digested with DpnI to leave only the newly amplified plasmid, transformed into XL10-Gold Ultracompetent cells, and grown on Terrific broth plates containing ampicillin. Positive colonies were grown for plasmid purification using a Qiagen Maxiprep kit. The full-length pO1C was sequenced to verify that only the desired mutation was present in the plasmid. Primers were designed using the Stratagene primer mutagenesis program, which limited us to a maximum of seven amino acid changes and was the basis for deciding on the regions to be mutated (http://www.genomics.agilent.com/CollectionSubpage.aspx?PageType=Tool&SubPageType=ToolQCPD&PageID=15).

Construction of the FMDV O1C full-length cDNA infectious clone and mutant O1C3A-PLDG.

Construction of the pO1C full-length cDNA IC from the highly virulent FMDV strain O1Campos/Bra/58 has been previously described in detail (15). pO1C3A-PLDG is a derivative of pO1C that contains a 4-amino-acid substitution (between residue positions 89 and 92) of 3A that was introduced by site-directed mutagenesis using full-length pO1C as a template pO1C and pO1C3A-PLDG were completely sequenced to confirm the presence of expected modifications and absence of unwanted substitutions.

Plasmid pO1C or its mutant version was linearized at the EcoRV site according to the poly(A) tract and used as a template for RNA synthesis using the MegaScript T7 kit (Ambion, Austin, TX) according to the manufacturer's protocols. BHK-21 cells were transfected with these synthetic RNAs by electroporation (Electrocell Manipulator 600; BTX, San Diego, CA) as previously described (15, 22). Briefly, 0.5 ml of BHK-21 cells at a concentration of 1.5 × 107 cells/ml in PBS were mixed with 10 μg of RNA in a 4-mm-gap BTX cuvette. The cells were then pulsed once (330 V, infinite resistance; capacitance, 1,000 μF), diluted in cell growth medium, and allowed to attach to a T-25 flask. After 4 h, the medium was removed, fresh medium was added, and the cultures were incubated at 37°C for up to 24 h.

The supernatants from transfected cells were passaged in LFBK-αVβ6 cells until a cytopathic effect appeared. After successive passages in these cells, virus stocks were prepared, and the viral genome completely sequenced using the Prism 3730xl automated DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems) as previously described (15).

Comparative ability of viruses to grow in cells of different origin.

Comparative growth curves between O1C and pO1C3A-PLDG viruses were performed in LFBK-αVβ6 and FBK cells. Preformed monolayers were prepared in 24-well plates and infected with the two viruses at MOIs of 0.01 (based on TCID50s previously determined in LFBK-αVβ6 cells). After 1 h of adsorption at 37°C, the inoculum was removed, and the cells were rinsed two times with ice-cold 145 mM NaCl–25 mM MES (pH 5.5) to remove residual virus particles. The monolayers were then rinsed with medium containing 1% fetal calf serum and 25 mM HEPES (pH 7.4) and incubated for 0, 4, 8, 24, or 48 h at 37°C. At appropriate times postinfection, the cells were frozen at −70°C, and the thawed lysates were used to determine titers by TCID50/ml in LFBK-αVβ6 cells. All samples were run simultaneously to avoid interassay variability. Plaque assays in LF-BK αVβ6 and FBK cell lines were performed as previously described (18).

Virulence of O1Cv and O1C3A-PLDGv viruses in cattle.

Animal experiments were performed under biosafety level 3 conditions in the animal facilities at PIADC according to a protocol approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Three steers (each 300 to 400 kg) were infected using the established aerosol inoculation method (23) with ∼107 PFU/steer of O1Cv or O1C3A-PLDGv virus, diluted in MEM containing 25 mM HEPES. Different viruses were inoculated in different animal rooms. Rectal temperatures and clinical examinations with sedation looking for secondary site replication (vesicles) were performed daily. Clinical scores were based on presence of vesicles in the mouth and feet, with a maximum score of 20 as previously described (23). The antemortem sample collection consisted of blood (to obtain serum) and nasal and oral swabs collected daily up to 10 days postinfection (dpi) and at 14, 17, and 21 dpi. Postmortem sample acquisition, performed at 21 dpi, consisted of the collection of tissues as previously described (23) from dorsal soft palate, dorsal nasal pharynx, retropharyngeal lymph node, and interdigital cleft.

After collection, clinical samples were divided into aliquots and frozen at ≤−70°C. One serum and one swab aliquot, collected each day from each animal, were used to perform viral titration by real-time reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) as described previously (23).

FMDV RNA quantitation by real-time RT-PCR.

FMDV real-time RT-PCR (rRT-PCR) was performed as previously described (23). The RNA copy numbers per milliliter of fluid (antemortem samples) or per milligram of tissue (postmortem samples) were calculated based on a O1 Campos-specific calibration curve developed with in vitro-synthesized RNA obtained from pO1C. For this, a known amount of FMDV RNA was 10-fold serial diluted in nuclease-free water and each dilution was tested in triplicate by FMDV rRT-PCR. Threshold cycle (CT) values from triplicates were averaged and plotted against FMDV RNA copy number.

RESULTS

FMDV nonstructural 3A protein interacts with the bovine host protein DCTN3.

A yeast two-hybrid system (24) was used to identify host cellular proteins that interact with FMDV 3A protein. Several host proteins were shown to specifically interact with 3A (Table 1). One of these host proteins, identified as bovine DCTN3 (NCBI reference sequence NM_001075660.1), was selected for further study (Fig. 1A). DCTN3 is a subunit of the dynactin complex which is a cofactor for the microtubule-based motor dynein, playing an important role in cell organization and transport (25).

TABLE 1.

Bovine proteins that interact with FMDV 3A, as determined by yeast-two hybrid

| Gene | Description | GenBank accession no. |

|---|---|---|

| DCTN3 | Dynactin 3 (p22) | XP_005210380.1 |

| KTN1 | Kinectin 1 (kinesin receptor) | NP_001095675.1 |

| ZG16B | Zymogen granule protein 16B | XP_002697975.3 |

| UBQLN1 | Ubiquilin 1 | NP_777053.1 |

| WHAMM | WAS protein homolog | NP_001178385.1 |

| BAG6 | BCL2-associated athanogene 6 | NP_001068834.2 |

FIG 1.

(A and B) Protein-protein interaction of FMDV 3A with bovine DCTN3 in the yeast two-hybrid system (A) and immunofluorescence staining (B). (A) Yeast strain AH109 was transformed with GAL4-binding domain (BD) fused to FMDV 3A (BD-3A) or a negative control, human lamin C (BD-LAM). These strains were then transformed with GAL4 activation domain (AD) fused to DCTN3 (AD-DCTN3) or T antigen (AD-Tag) as indicated above each lane. Spots of strains expressing the indicated constructs containing 2 × 106 yeast cells were placed on selective media to screen for protein-protein interaction in the yeast two-hybrid system: either SD−Ade/His/Leu/Trp plates (−ALTH) or nonselective SD−Leu/Trp (−TL) for plasmid maintenance only. (B) Analysis of the distribution of DCTN3 and FMDV 3A proteins in MCF-10A cells. Cells were infected or mock infected with FMDV O1Cv and processed by immunofluorescence staining at 1.5 hpi as described in Materials and Methods. FMDV 3A was detected with MAb 2C2 and visualized with Alexa Fluor 594 (red). DCTN3 was detected with MAb GTX115607 and visualized with Alexa Fluor 488 (green). Yellow indicates colocalization of Alexa Fluor 594 and 488 in the merged image. (C) Protein-protein interactions by the mammalian two-hybrid system using the indicated plasmids were measured by absorbance at 405 nm as determined by CAT ELISA, as described in Materials and Methods.

To confirm that 3A-DCTN3 interaction occurs during FMDV infection of host cells, the localization of 3A and DCTN3 during infection was assessed using double-label immunofluorescence and deconvolution microscopy in cells infected with FMDV. MCF-10A cells were infected (MOI = 10) or mock-infected with FMDV O1Cv. Cells were fixed on glass coverslips at 30-min intervals up to 4 h after infection and stained using monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) that exhibit specific fluorescence for FMDV 3A (MAb 2C2) or DCTN3 (MAb GTX114607). The results indicated a clear colocalization of FMDV 3A and DCTN3 proteins at 1.5 h postinfection (hpi), the appearance of distinct punctuate spots of DCTN3 that colocalizes with 3A during viral infection are distributed in the cell cytoplasm, along with small ones of each of the individual protein (Fig. 1B), supporting the hypothesis that interaction between these two proteins occurs during viral infection. In addition, the confirmation of the 3A-DCTN3 interaction was performed (26). MCF10A cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids. Cell lysates were analyzed for CAT expression 48 h. The results (Fig. 1C) show a clear interaction between 3A-DCTN3, further supporting the hypothesis that this interaction can occur in cells susceptible to FMDV.

Overexpression of host DCTN3 protein results in decreased FMDV replication.

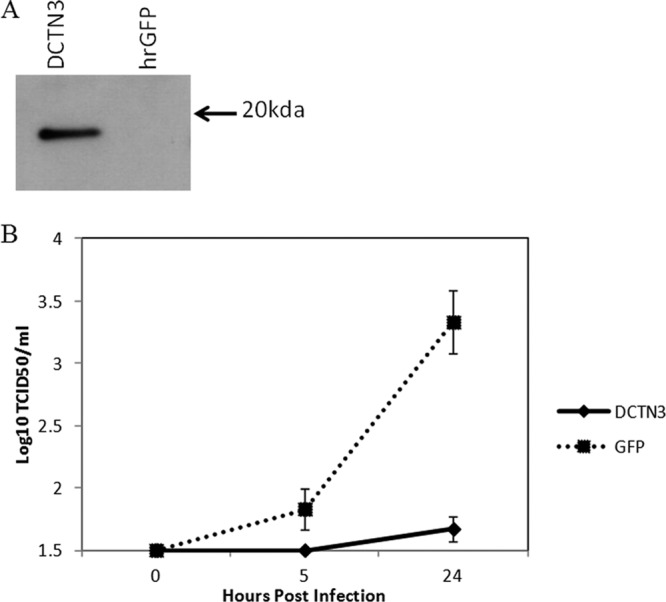

To assess the role of DCTN3 in FMDV replication, we utilized an overexpression plasmid for DCTN3 and evaluated virus yield in cells overexpressing DCTN3. Overexpression of DCTN3 in transfected cells was assessed at 19 h posttransfection by Western blotting (Fig. 2B). Furthermore, MCF-10A cells overexpressing DCTN3 or green fluorescent protein (GFP) were infected (MOI = 0.1) with FMDV O1Cv, and virus present in the cell culture supernatant was measured hourly between 0 and 5 hpi and at 24 hpi. A considerable reduction (∼2 logs) in virus titer was observed in cells overexpressing DCTN3 compared to cells overexpressing GFP (Fig. 2A). These results indicate that overexpression of DCTN3 causes a decrease in virus yield.

FIG 2.

Viral yields from FMDV infections in MCF-10A cells overexpressing DCTN3. (A) MCF-10A cells were transfected either with a plasmid encoding DCTN3 (pDCTN3) or GFP (hrGFP) as a control as described in Materials and Methods. (B) After transfection, triplicate plates were infected with FMDV O1Cv (MOI = 0.1). Titers were determined in BHK-21 cells and expressed as log10 TCID50/ml. The Western blot shows the endogenous intracellular levels of DCTN3in in MCF-10A cells transfected with either pDCTN3 or hrGFP.

Disruption of intracellular dynactin arrangement decreases viral yield.

As mentioned previously, DCTN3 is a subunit of the dynactin complex which is a cofactor for the microtubule-based motor dynein. Dynactin-dynein complexes have been implicated in several important subcellular functions involving intracellular organelle transport. To assess the role of DCTN3 in FMDV replication, we attempted to disrupt dynactin-dynein complexes in FMDV-infected cells that were independently transfected with two plasmids known to disrupt the intra- and intersubunit contacts of dynactin (19). One of the plasmids encodes the first α-helical coiled-coil domain residues 221 to 509 (CC1 domain), from p150/Glued tagged to mEGFP (pmEGFP-C1-CC1), and the second one encodes a 50/dynamitin tagged to mEGFP (pmEGFP-N1-p50). MCF-10A cells were transfected with pmEGFP-C1-CC1, pmEGF-N1-p50, or hrGFP as a control and then infected at 19 h posttransfection with an MOI of 1 with FMDV O1Cv and virus yields in the extracellular media were assessed at 0, 5, and 24 hpi. The results demonstrated that while overexpression of control hrGFP does not affect virus replication, cells overexpressing the dominant-negative forms of dynactin presented a significant reduction (>2 logs) in virus titer (Fig. 3A). Expression of each of the proteins encoded by the different constructs was demonstrated by direct fluorescence in the transfected cells (Fig. 3B). These results indicate that lack of integrity of the dynactin arrangement in the infected cell negatively affects virus yield. Therefore, alteration of the dynactin complex by either the overexpression of DCTN3 or the disruption of dynactin-dynein complexes clearly alters the replication of FMDV.

FIG 3.

Effect of disrupting the intracellular dynactin arrangement on FMDV yield. MCF-10A cells were transfected with either plasmid pmEGFP-C1-CC1, pmEGF-N1-p50, or hrGFP, as a control as described in Materials and Methods. (A) After transfection, triplicate plates were infected with FMDV O1Cv (MOI = 0.1). Titers were determined in BHK-21 cells and expressed as log10 TCID50/ml. (B) EGFP expression for the indicated plasmid was monitored by fluorescent microcopy.

Identification of the DCTN3 binding site on FMDV 3A.

To further analyze the role of DCTN3-3A protein interaction during FMDV replication and pathogenesis, it is important to determine the binding site(s) for DCTN3 in the 3A protein. We utilized an alanine scanning mutagenesis approach by using site-directed mutagenesis to develop a set of 22 mutant 3A proteins containing sequential stretches of six to eight amino acids where the native amino acid residues were substituted by alanine residues (Fig. 4A). These mutated 3A proteins were assessed for their ability to bind DCTN3 utilizing the yeast two-hybrid system. 3A proteins containing mutations in areas 3, 10, 11, and 13 were unable to bind DCTN3 (Fig. 4B). To ensure that all 3A alanine mutants were still able to be expressed in the yeast two-hybrid system, protein KTN1-AD (kinectin 1) another bovine host protein that was detected as a binding partner for 3A) was used as an internal control. KTN1 was unable to interact with 3A mutants 3, 10 and 11 but strongly interacts with 3A mutant 13, suggesting that the lack of interaction between DCTN3 and 3A mutants 3, 10, and 11 can be nonspecific (Fig. 4B). Therefore, we focused on the 3A area covered by mutant 13.

FIG 4.

Mapping DCTN3 binding site in FMDV 3A using alanine scan mutagenesis. (A) Each alanine 3A mutant name is followed, in parentheses, by the amino acid residues mutated for that mutant. All of the indicated native residues were mutated to an alanine. (B) FMDV 3A alanine mutants were assessed in their binding activity to DCTN3 using the yeast two-hybrid system. Yeast strain AH109 was transformed with either GAL4-binding domain (BD) fused to FMDV 2C (3A-BD), the indicated FMDV 3A mutation, or as a negative-control human lamin C (LAM BD). These strains were then transformed with GAL4 activation domain (AD) fused to DCTN3 (DCTN3-AD). Strains expressing the indicated constructs containing 2 × 106 yeast cells were spotted onto selective media to evaluate protein-protein interaction in the yeast two-hybrid system, using either SD−Ade/His/Leu/Trp plates (−ALTH) or nonselective SD−Leu/Trp plates (−TL) for plasmid maintenance only.

To enhance the mapping of critical areas recognized by DCTN3 in FMDV 3A, the reactivity of DCTN3 with the 3A protein belonging to FMDV O/TAW/97 was assessed. O/TAW/97 was selected due to its variability in the amino acid sequence covered by the 3A.13 mutant (residues MVDDAVN in positions 85 to 91 of 3A protein in serotype O1C) (Fig. 5A). Interestingly, O/TAW/97 protein failed to interact with DCTN3 (data not shown). Amino acid sequence comparison between residues 85 to 91 of 3A from subtypes O1C and O/TAW/97 demonstrated that the main discrepancy between their 3A proteins is that amino acid sequence AVNE at positions 89 to 92 is substituted by PLDG in O/TAW/97. Although mutant 3A.13 was in positions 85 to 91 and the PLDG mutation was smaller but spanned an additional residue at position 92 that was not covered by 3A.13, we decided to mutate PLDG, since it was similar to O/TAW/97, to increase the likelihood of recovering a mutant virus. O1C 3A mutants having substituted native residues at positions 89 to 92 by those encoded in O/TAW/97 demonstrated that substitution of native residues AVNE by PLDG residues completely abolished reactivity of 3A with DCTN3 (Fig. 5B), indicating that residues at positions 89 to 92 play a critical role in the 3A-DCTN3 interaction.

FIG 5.

Mapping DCTN3 binding site in FMDV 3A using comparative genomics. (A) Alignment of amino acid sequence among FMDV from different serotypes. The area between amino acid residues 89 and 92 is shaded. (B) FMDV O1C 3A (BD-3A), as well as mutated version of 3A representing polyalanine mutant 3A.13 (BD-3A.13), and mutant 3A.PLDG (BD-3A.PLDG) were tested in their ability to bind bovine DCTN3 in the yeast two-hybrid system. The methodological details are as described in Fig. 2.

Generation of a mutant FMDV virus harboring mutated 3A protein.

To understand the significance of the interaction between FMDV 3A and host DCTN3, reverse genetics was used to assess the effect of 3A mutations identified as critical in mediating the interaction between 3A and DCTN3. Infectious clones (ICs) of parental FMDV O1C (pO1C) (8) and a mutated FMDV O1C harboring the substituted native amino acid residues between positions 89 and 92 (AVNE) in nonstructural protein 3A of pO1C by the corresponding residues in O/TAW/97 (PLDG) were used; pO1C3A-PLDG was constructed as described in Materials and Methods.

These IC constructs were then used to produce the corresponding RNAs by in vitro transcription. RNA transcripts derived from pO1C or pO1a3A-PLDG were used to transfect BHK-21 cells by electroporation and then subjected to five passages in LF-BK cells expressing the bovine integrin αVβ6 (LFBK-αVβ6) (17) to amplify the clone-derived viruses. Sequencing of the entire genome of recovered viruses (O1Cv and O1C3A-PLDGv) verified that they were identical to the parental DNAs, confirming that only the desired mutations were incorporated into the viruses.

O1C3A-PLDG virus has a decreased ability to grow in bovine primary cells.

To evaluate the role of the 3A-DCTN3 interaction in the replication of FMDV, multistep growth curves were performed using different cell substrates to comparatively assess in vitro growth characteristics of O1Cv and O1C3A-PLDGv viruses (Fig. 6). Cells were infected at an MOI of 0.01 based on virus titers determined first using the LFBK-αvβ6 cell line. Samples were collected at regular intervals between 0 and 48 hpi. The results demonstrated that viruses O1Cv and O1C3A-PLDGv exhibited similar growth characteristics and reached comparable titers in LFBK-αvβ6 cells (Fig. 6A). The ability of these viruses to replicate in primary fetal bovine kidney cell (FBK) cultures was assessed under experimental conditions similar to those described for LFBK-αVβ6 cells. The results demonstrated that O1C3A-PLDGv virus had a substantially decreased ability to replicate in FBKs compared to virus O1Cv. Differences of ∼1,000-fold were observed in the titer values of samples harvested at 24 and 48 hpi (Fig. 6A).

FIG 6.

Growth characteristics of FMDV O1Cv and O1C3A-PLDGv. (A) In vitro growth curves of O1Cv and O1C3A-PLDGv (MOI = 0.01) in LF-BK-αVβ6 and FBK cells. Samples obtained at the indicated time points were titrated in LF-BK-αVβ6 cells, and virus titers are expressed as TCID50/ml. (B) Plaques corresponding to O1Cv and O1C3A-PLDGv viruses in LF-BK-αVβ6 and FBK cells. Infected cells were incubated at 37°C under a tragacanth overlay and stained with crystal violet at 48 hpi. Plaques from appropriate dilutions are shown.

The decreased ability of virus O1C3A-PLDGv to replicate in primary bovine cells was further analyzed in a standard plaque assay performed in LFBK-αVβ6 and FBK cell cultures (Fig. 6B). The results demonstrated that viruses O1Cv and O1C3A-PLDGv both produced a similar large plaque size in LFBK-αVβ6 cells. However, while virus O1Cv produced smaller plaques in FBK cells than those produced in LFBK-αVβ6 cells, virus O1C3A-PLDGv was completely unable to produce any visible plaques, similarly to what has been previously described in O/TAW/97 (12). Thus, the substitution in 3A harbored by O1C3A-PLDGv virus undermined its ability of the virus to replicate in primary bovine cell cultures.

Assessment of FMDV O1Cv and O1C3A-PLDGv virulence in cattle.

Virulence of both viruses, O1Cv and O1C3A-PLDGv, in cattle was assessed utilizing an aerosol inoculation method developed in our laboratory (23). This method was chosen since it appears to more closely simulate the natural route of infection compared to the intradermolingual route. Three steers were infected with ∼107 PFU of O1Cv or O1C3A-PLDGv virus/steer, diluted in MEM. Infection and clinical signs were monitored daily as described previously (23). The results demonstrated that the three animals (animals 72, 73, and 74) inoculated with the O1Cv virus developed severe clinical FMD. Lesions typical of FMD appeared by 3 or 4 dpi and reached the maximum clinical score (mouth and 4 feet affected with vesicles) by 4 or 5 dpi (Fig. 7). All three animals had fever (>40°C) from 3 to 7 dpi (results not shown). Viremia lasted 4 to 6 days, starting at 2 dpi, and virus shedding was detected in nasal swabs from all animals beginning at 1 dpi and was undetectable by 10 or 14 dpi; virus shedding was detected in oral swabs starting at 1 to 3 dpi until, at least, 10 dpi (Fig. 7).

FIG 7.

Assessment of O1Cv and O1C3A-PLDGv virus virulence in cattle. Steers were inoculated with 107 PFU of either O1Cv (animals 72, 73, and 74) or O1C3A-PLDGv (animals 69, 70, and 71) according to the aerosol inoculation method. The presence of clinical signs (clinical scores), and the virus yields (quantified as the log10 of viral RNA copies/ml of sample) in serum and oral and nasal swabs were determined daily during the observational period.

Conversely, the three animals inoculated with the O1C3A-PLDGv virus (animals 69, 70, and 71) developed FMD with clinical signs differing in severity and onset dynamics. Animal 69 presented with lesions typical of FMD by 8 dpi and reached a clinical score of 12 (mouth and one foot with small vesicles plus 2 feed affected with big vesicles) by 9 dpi (Fig. 7). Viremia lasted 4 days, with virus shedding detected in nasal and oral swabs beginning at 6 dpi until 14 dpi (Fig. 7). Animal 70 presented with an earlier disease state with lesions by 6 dpi, reaching the maximum clinical score of 20 (mouth and 4 feet affected with big vesicles) by 8 dpi. Viremia lasted 4 days, with virus shedding detected in nasal and oral swabs beginning at 6 dpi. Finally, animal 71 presented a delayed disease, developing FMD lesions not earlier than day 11, reaching by 14 dpi a clinical score of 16 (all 4 feet affected with big vesicles). Viremia was only detected at comparatively low levels by 10 and 14 dpi, a length of 5 days, while virus shedding in nasal and oral swabs began at 7 dpi and was still detectable until 21 dpi at low levels. Although it showed heterogeneous behavior in cattle, it is clear that O1C3A-PLDGv virus induced a clearly delayed (between 2 to 10 days in the appearance of first lesions and between 4 and 10 days in reaching the maximum clinical score) and slightly milder clinical disease than its parental virus O1Cv.

O1C3A-PLDGv virus isolated from infected cattle has altered the amino acid sequence of 3A that mediate binding to host protein DCTN3.

As described earlier, animals inoculated with O1C3A-PLDGv virus presented a delayed and milder disease than those infected with the virulent parental virus O1Cv. Viruses isolated from secondary (generalized) lesions of the inoculated cattle inoculated with either virus were partially sequenced, targeting the 3A area. Interestingly, while viruses isolated from animals inoculated with O1C did not show differences with the parental strain, viruses obtained from all three animals inoculated with O1C3A-PLDGv presented with changes in amino acid residue P89 of the PLDG sequence. Amino acid residue P89 was substituted by A89 in animal 69 and by L89 in animals 70 and 71. No additional amino acid substitutions were detected in the sequence of 3A protein of the viruses isolated from the three animals. Therefore, substitution of P89 by A (the native amino acid residue at position 89 of 3A in O1Cv virus) or L appears to be associated with a change in virus attenuation since in all three cases there is an association between the development of generalized lesions and the emergence of viruses with substitutions at position 89 of the 3A protein.

It could be hypothesized that the A89P substitution in 3A is responsible for disrupting 3A binding to DCTN3. In order to assess this possibility, the A89P mutation in the 3A protein was tested for the ability to interact with DCTN3 in the two-hybrid system. Interestingly, FMDV O1C 3A containing only the A89P substitution was able to disrupt the binding to DCTN3 (Fig. 8). To test whether the other amino acid substitution recovered from the infected animals, L89, was could allow binding to DCTN3, the mutation A89L was tested in the two-hybrid, demonstrating that A89L was able to bind DCTN3 (Fig. 8). These results indicate that amino acid 89 as an alanine or a leucine allows binding with DCTN3, but when mutated to a proline, disrupts DCTN3 binding. These results suggest that residue 89 in 3A is critical for DCTN3 binding and support the possibility that 3A-DCTN3 interaction may constitute a critical event, leading to the production of clinical FMD in cattle.

FIG 8.

Analysis of DCTN3 binding activity with mutated 3A proteins FMDV O1C 3A (BD-3A), mutant 3A.PLDG (BD-3A.PLDG), and mutants BD-3A.P and BD-3A.L were tested in their ability to bind bovine DCTN3 in the yeast two-hybrid system. The methodological details are as described in Fig. 2.

DISCUSSION

The mechanisms FMDV utilizes to manipulate host cell machinery for its own replication and to evade the host immune response are not fully understood. One potential mechanism FMDV may use to manipulate the host cell involves interaction with cellular proteins, enabling the virus to subvert natural cellular pathways in favor of its own replication. In our previous work that focused on cellular proteins that interact with FMDV nonstructural protein 2C, we determined that viral 2C was able to bind cellular Beclin1 to prevent autophagosome-lysosome fusion, favoring virus survival (27). We also discovered that 2C binds with cellular vimentin, a protein that forms a cage-like structure around 2C early during infection but must later be resolved for virus replication to progress (13). Here, we report that FMDV nonstructural protein 3A binds to DCTN3, a subunit of the dynactin complex that acts as a cofactor for the microtubule-base motor dynein.

Many different viruses modulate the dynein pathway, suggesting that manipulation of the dynactin complex is necessary for successful viral replication. Adenovirus utilizes the dynactin complex to speed up intracellular movement of the viral capsid (10), which has been shown to directly bind dynein (6), and disruption of dynein by either pmEGFP-C1-CC or pmEGFP-N1-p50 caused decreased viral yield (19). In the case of dengue virus, dynein has been shown to be involved in both viral entry and egress and decreasing dynein light chain by small interfering RNA caused a decrease in viral yield, and overexpression of p50 decreased the amount of cellular viral proteins (5, 27). Polio virus has been demonstrated to directly bind dynein in vitro (14); additionally, poliovirus 3A binds LIS1, a component of the dynein/dynactin complex. It has previously been shown that dynactin is involved in the organization of vimentin filaments (14), and vimentin reactivity to FMDV nonstructural protein 2C is critical for virus replication.

To analyze the role of DCTN3 binding to FMDV 3A in virus replication, we attempted to manipulate the dynactin complex in cells infected with FMDV. Overexpression of DCTN3 and expression of constructs pmEGFP-C1-CC1 and pmEGF-N1-p50, which cause a disruption in the dynein pathway, resulted in a significant decrease in viral yield. It is not clear why overexpression of DCTN3 decreases virus yield. Perhaps binding of 3A to DCTN3 sequesters DCTN3, facilitating an unknown step of virus replication. Alternatively, overexpression of DCTN3 may have the similar effect of disrupting the dynein pathway as the expression of pmEGFP-C1-CC1 and pmEGF-N1-p50 do. Moreover, it appears that an intact dynein cellular pathway is required for efficient FMDV replication. Further work is necessary to clarify the exact role of 3A-DCTN3 binding in that process.

Alanine scanning allowed the location of the physical binding site of DCTN3 to be identified in residues 85 to 91 of 3A. Sequence alignment of several FMDV 3A isolates indicated that FMDV O/TAW/97 presented a four-amino-acid substitution in this area (residues 89 to 92) compared to FMDV O1C (AVNE to PLDG). These substitutions, when included in the context of FMDV O1C 3A, efficiently disrupt binding with DCTN3. A recombinant viable virus containing the PLDG residues in 3A, O1C3A-PLDGv, replicated at a rate similar to the parental virus in LFBK-αvβ6 cells but replicated at a decreased rate in primary FBK cells. Interestingly, O1C3A-PLDGv, replicated at a rate similar to the parental virus in FPK cells (data not shown). A similar replication pattern is observed with FMDV O/TAW/97 (28) and with a recently reported recombinant FMDV O1Cv virus harboring a deletion in 3A between residues 87 to 106 (therefore lacking the DCTN3 binding site) (12). Perhaps binding between FMDV 3A and host DCTN3 may contribute to the host range specificity of the virus.

Our previous study analyzing the specific effect of the deletion in 3A and the effect on virulence in bovine (12), and the inability of DCTN3 to bind FMDV O/TAW/97, suggests the possibility that the host range could be determined by the ability of 3A to bind DCTN3; however, the DCTN3 protein appears to be highly conserved between swine and bovine, sharing 96% of the amino acid residues between species, so further experimentation would have to be done to determine whether the small differences in DCTN3 between species is responsible for the changes in host range determined with FMDV O/TAW.

As mentioned above, FMDV O1C3A-PLDGv produced a delayed, somewhat mild disease in cattle, suggesting a possible role of 3A-DCTN3 interaction in virus virulence in cattle. It was impossible to recover virus from O1C3A-PLDGv-infected animals until the disease was evident. Virus recovered at late stages of disease presented an amino acid substitution of a leucine or an alanine at position 89. Interestingly, when evaluated by yeast two-hybrid assay, the disruption of DCTN3 binding only occurred when residue 89 was a proline, suggesting that the viruses with the A/L at position 89 were able to regain the ability to bind to DCTN3 and that this binding may be important for viral virulence.

The results reported here identify, for the first time, cellular protein DCTN3 as an interaction partner for FMDV protein 3A. The results also indicate that FMDV replication appears to rely on an intact dynein pathway in vitro. Importantly, the FMDV 3A-DCTN3 interaction appears critical for virus replication in cattle, as virus quickly reverted during the infection to regain DCTN3 binding. This presents new possibilities to explore FMDV pathogenesis and the virus requirements of virus-host interaction necessary to produce disease. In addition, further work needs to be done to understand other host protein-viral protein relationships and how the virus exploits or evades specific cellular pathways for its own survival.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Martin Engelke and Bettina Cardel (University of Zurich) for the pmEGFP-C1-CC1 and pmEGF-N1-p50 plasmids. We thank Elizabeth Bishop and Ethan Hartwig for help with RNA in vitro transcription, cell transfections, and sequencing of mutant viruses. We also thank Melanie Prarat for editing the manuscript.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 18 December 2013

REFERENCES

- 1.Grubman MJ, Baxt B. 2004. Foot-and-mouth disease. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 17:465–493. 10.1128/CMR.17.2.465-493.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rowlands DJ. 2003. Special issue—Foot-and-mouth disease: preface. Virus Res. 91:1. 10.1016/S0168-1702(02)00264-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Belsham GJ. 1993. Distinctive features of foot-and-mouth disease virus, a member of the picornavirus family; aspects of virus protein synthesis, protein processing and structure. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 60:241–260. 10.1016/0079-6107(93)90016-D [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Knowles NJ, Davies PR, Henry T, O'Donnell V, Pacheco JM, Mason PW. 2001. Emergence in Asia of foot-and-mouth disease viruses with altered host range: characterization of alterations in the 3A protein. J. Virol. 75:1551–1556. 10.1128/JVI.75.3.1551-1556.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li S, Gao M, Zhang R, Song G, Song J, Liu D, Cao Y, Li T, Ma B, Liu X, Wang J. 2010. A mutant of infectious Asia 1 serotype foot-and-mouth disease virus with the deletion of 10-amino-acid in the 3A protein. Virus Genes 41:406–413. 10.1007/s11262-010-0529-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nunez JI, Baranowski E, Molina N, Ruiz-Jarabo CM, Sanchez C, Domingo E, Sobrino F. 2001. A single amino acid substitution in nonstructural protein 3A can mediate adaptation of foot-and-mouth disease virus to the guinea pig. J. Virol. 75:3977–3983. 10.1128/JVI.75.8.3977-3983.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lama J, Sanz MA, Carrasco L. 1998. Genetic analysis of poliovirus protein 3A: characterization of a non-cytopathic mutant virus defective in killing Vero cells. J. Gen. Virol. 79(Pt 8):1911–1921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giraudo AT, Beck E, Strebel K, de Mello PA, La Torre JL, Scodeller EA, Bergmann IE. 1990. Identification of a nucleotide deletion in parts of polypeptide 3A in two independent attenuated aphthovirus strains. Virology 177:780–783. 10.1016/0042-6822(90)90549-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beard CW, Mason PW. 2000. Genetic determinants of altered virulence of Taiwanese foot-and-mouth disease virus. J. Virol. 74:987–991. 10.1128/JVI.74.2.987-991.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dunn CS, Donaldson AI. 1997. Natural adaption to pigs of a Taiwanese isolate of foot-and-mouth disease virus. Vet. Rec. 141:174–175. 10.1136/vr.141.7.174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang PC, Chu RM, Chung WB, Sung HT. 1999. Epidemiological characteristics and financial costs of the 1997 foot-and-mouth disease epidemic in Taiwan. Vet. Rec. 145:731–734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pacheco JM, Gladue DP, Holinka LG, Arzt J, Bishop E, Smoliga G, Pauszek SJ, Bracht AJ, O'Donnell V, Fernandez-Sainz I, Fletcher P, Piccone ME, Rodriguez LL, Borca MV. 2013. A partial deletion in nonstructural protein 3A can attenuate foot-and-mouth disease virus in cattle. Virology 446:260–267. 10.1016/j.virol.2013.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gladue DP, O'Donnell V, Baker-Branstetter R, Holinka LG, Pacheco JM, Sainz IF, Lu Z, Ambroggio X, Rodriguez L, Borca MV. 2013. Foot-and-mouth disease virus modulates cellular vimentin for virus survival. J. Virol. 87:6794–6803. 10.1128/JVI.00448-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Egan MJ, Tan K, Reck-Peterson SL. 2012. Lis1 is an initiation factor for dynein-driven organelle transport. J. Cell Biol. 197:971–982. 10.1083/jcb.201112101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Borca MV, Pacheco JM, Holinka LG, Carrillo C, Hartwig E, Garriga D, Kramer E, Rodriguez L, Piccone ME. 2012. Role of arginine-56 within the structural protein VP3 of foot-and-mouth disease virus (FMDV) O1 Campos in virus virulence. Virology 422:37–45. 10.1016/j.virol.2011.09.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Swaney LM. 1988. A continuous bovine kidney cell line for routine assays of foot-and-mouth disease virus. Vet. Microbiol. 18:1–14. 10.1016/0378-1135(88)90111-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Larocco M, Krug PW, Kramer E, Ahmed Z, Pacheco JM, Duque H, Baxt B, Rodriguez LL. 2013. A continuous bovine kidney cell line constitutively expressing bovine alphavss6 integrin has increased susceptibility to foot and mouth disease virus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 51:1714–1720. 10.1128/JCM.03370-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pacheco JM, Piccone ME, Rieder E, Pauszek SJ, Borca MV, Rodriguez LL. 2010. Domain disruptions of individual 3B proteins of foot-and-mouth disease virus do not alter growth in cell culture or virulence in cattle. Virology 405:149–156. 10.1016/j.virol.2010.05.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Engelke MF, Burckhardt CJ, Morf MK, Greber UF. 2011. The dynactin complex enhances the speed of microtubule-dependent motions of adenovirus both toward and away from the nucleus. Viruses 3:233–253. 10.3390/v3030233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chien CT, Bartel PL, Sternglanz R, Fields S. 1991. The two-hybrid system: a method to identify and clone genes for proteins that interact with a protein of interest. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 88:9578–9582. 10.1073/pnas.88.21.9578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fields S, Song O. 1989. A novel genetic system to detect protein-protein interactions. Nature 340:245–246. 10.1038/340245a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mason PW, Rieder E, Baxt B. 1994. RGD sequence of foot-and-mouth disease virus is essential for infecting cells via the natural receptor but can be bypassed by an antibody-dependent enhancement pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 91:1932–1936. 10.1073/pnas.91.5.1932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pacheco JM, Arzt J, Rodriguez LL. 2010. Early events in the pathogenesis of foot-and-mouth disease in cattle after controlled aerosol exposure. Vet. J. 183:46–53. 10.1016/j.tvjl.2008.08.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fields S, Sternglanz R. 1994. The two-hybrid system: an assay for protein-protein interactions. Trends Genet. 10:286–292. 10.1016/0168-9525(90)90012-U [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karki S, LaMonte B, Holzbaur EL. 1998. Characterization of the p22 subunit of dynactin reveals the localization of cytoplasmic dynein and dynactin to the midbody of dividing cells. J. Cell Biol. 142:1023–1034. 10.1083/jcb.142.4.1023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Luo Y, Batalao A, Zhou H, Zhu L. 1997. Mammalian two-hybrid system: a complementary approach to the yeast two-hybrid system. Biotechniques 22:350–352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gladue DP, O'Donnell V, Baker-Branstetter R, Holinka LG, Pacheco JM, Fernandez-Sainz I, Lu Z, Brocchi E, Baxt B, Piccone ME, Rodriguez L, Borca MV. 2012. Foot-and-mouth disease virus nonstructural protein 2C interacts with Beclin1, modulating virus replication. J. Virol. 86:12080–12090. 10.1128/JVI.01610-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pacheco JM, Mason PW. 2010. Evaluation of infectivity and transmission of different Asian foot-and-mouth disease viruses in swine. J. veterinary science 11:133–142. 10.4142/jvs.2010.11.2.133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]