Abstract

Objective

To prospectively characterize acute hyperammonemic episodes in patients with urea cycle disorders (UCD) in regards to precipitating factors, treatments and utilization of medical resources.

Study design

Prospective, longitudinal observational study of hyperammonemic episodes in patients with UCD enrolled in the NIH sponsored Urea Cycle Disorders Consortium Longitudinal Study. An acute hyperammonemic event was defined as plasma ammonia level > 100 µmol/L. Physician reported data regarding the precipitating event and laboratory and clinical variables were recorded in a central database.

Results

A total of 128 patients with UCD experienced 413 hyperammonemia events. Most patients experienced between 1–3 (65%) and 4–6 (23%) hyperammonemia events since the study inception, averaging less than one event/year. The most common identifiable precipitant was Infection (33%), 24% of which were due to upper/lower respiratory tract infections. Indicators of increased morbidity were seen with Infection: increased hospitalization rates (P=0.02), longer hospital stays (+2.0 days, P = 0.003) and increased use of intravenous ammonia scavengers (+45–52%, P = 0.003–0.03).

Conclusions

Infection is the most common precipitant of acute hyperammonemia in patients with UCD and is associated with indicators of increased morbidity (ie, hospitalization rate, length of stay, use of IV ammonia scavengers). These findings suggest that the catabolic and immune effects of infection may be a target for clinical intervention in inborn errors of metabolism.

The complete urea cycle is present in the liver and plays a critical role in the incorporation of excess nitrogen (ie, ammonia) into urea. Portions of the cycle are present throughout the rest of the body and affect arginine production, nitric oxide metabolism, and polyamine production. [1] Urea cycle disorders (UCD) are caused by loss of function in any of a group of enzymes responsible for the elimination of neurotoxic ammonia. The incidence of these disorders has been estimated at approximately 1 in 30,000 live births.[2] UCD may be divided into proximal disorders (N-acetylglutamate synthetase (NAGS), carbamoyl phosphate synthase (CPS1), and ornithine transcarbamylase (OTC) deficiencies), in which ammonia disposal is severely impaired, or as distal disorders (argininosuccinate synthetase (ASS), argininosuccinate lyase (ASL), and arginase (ARG1) deficiencies), in which ammonia disposal may not be as severely compromised.

The term precipitant is used to describe events that trigger an acute deterioration in metabolic status. In UCD, this acute deterioration in metabolic status is characterized by potentially life-threatening episodes of hyperammonemia. Acute hyperammonemia in UCD may be precipitated by any factor that affects metabolic balance such as: dietary indiscretion, enhanced protein catabolism due to dietary over-restriction, or infection. Intercurrent infection is the most common precipitant of acute hyperammonemia, accounting for 34% of episodes, with respiratory viruses being a leading cause.[3, 4] Increased nitrogen breakdown secondary to catabolism during these episodes of intercurrent illness is likely a major contributor to acute hyperammonemia.[5] It is a commonly held belief amongst physicians caring for patients with UCD that intercurrent infection may result in more severe hyperammonemia episodes with increased morbidity.[6] However, formal studies exploring the various clinical variables of hyperammonemia precipitants are lacking.

Given these common perceptions, our goal was to characterize interim hyperammonemia events and their severity due to various precipitating factors. Using the data from the Urea Cycle Disorders Consortium Longitudinal Study[4], we examined various variables of interim hyperammonemia events including types of precipitants, plasma ammonia levels, hospital admission rates, length of stay, and hospital based medical management.

METHODS

Participants in the longitudinal study of the National Institutes of Health–sponsored Rare Diseases Clinical Research Consortium for UCD (RDCRN-UCD, U54RR19454 and U54HD61221) were included.[4] The goal of the RDCRN-UCD is to perform collaborative clinical research on UCD in the form of an observational longitudinal study. Patients with UCD were recruited at 16 hospital based study sites (http://rarediseasesnetwork.epi.usf.edu/ucdc/centers/index.htm) in the US (13), Canada (1) and Europe (2) during a 5 ½ year period. These hospital centers specialize in the care of patients with inborn errors of metabolism where study participants underwent periodic clinical evaluation. Sources of referral to the longitudinal study included: patient self-referral through the Rare Diseases Clinical Research Network, or referral by a medical care provider, prenatal diagnostic center, or the National Urea Cycle Disorders Foundation. Inclusion criteria for hyperammonemia events included all age groups, and all UCD diagnoses were eligible: NAGS, CPS1, OTC, ASS, ASL, ARG1, and citrin and ornithine transporter defects. Physician recorded interim event data, collected as part of the study, included all hospitalizations and urgent care visits for symptoms and signs suspicious of acute hyperammonemia. All participating members of the National Institutes of Health–approved Rare Diseases Clinical Research Consortium for UCD obtained local institutional review board approval.

The study design is a prospective cohort analysis of all physician reported interim hyperammonemic events recorded after enrollment in the RDCRN-UCD longitudinal study between February 6, 2006 and April 30, 2012. Interim events were defined as plasma ammonia level > 100 µmol/L requiring a hospitalization, emergency department or urgent care visit. Demographic information, history, clinical and laboratory findings were recorded by the treating medical professional and entered into the database, including the suspected hyperammonemia trigger.

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics are presented as number of subjects or events, proportions, and means with standard deviations. To examine the association between hyperammonemia morbidity markers and hyperammonemia precipitants, the generalized estimating equation assuming compound symmetry correlation structure was employed to consider within subject correlation among those multiple measurements from the same subject. A Poisson distribution was assumed for the count of morbidity markers during the study duration as an outcome, and a normal distribution for continuously measured markers.

P-values less than 0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance. All reported p-values are two-sided without adjustment of multiple testing. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

A total of 562 patients with UCD were enrolled in the Longitudinal Study database as of April 30, 2012. A total of 128 patients experienced 413 hyperammonemia events since their respective enrollments (Table I). Of these 128 patients, 79% were in the pediatric age range (< 18 years of age). The majority of subjects reporting ≥1 hyperammonemia event had OTC deficiency (52%) followed by citrullinemia (ASD, 20%) and argininosuccinic aciduria (ALD, 15%). A slightly higher proportion of patients with UCD studied were female (59%), due to the large contribution of OTC carrier patients (i.e. X-linked disorder). Age at diagnosis, determined by retrospective review, showed a broad range from 6.9 – 2191.5 days (6.0 years), with most patients being identified by clinical presentation (83%).

Table I.

Characteristics of patients experiencing at least one interim acute hyperammonemia event. NAGSD – N-acetylglutamate synthase deficiency; CPS1D – carbamoyl phosphate synthetase deficiency; OTCD – ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency; ASD – argininosuccinate synthetase deficiency; ALD – argininosuccinate lysase deficiency; ARGD – arginase deficiency; CITRD – citrin deficiency.

| UCD subtype | NAGSD |

CPS1D |

OTCD |

ASD |

ALD |

ARGD |

CITRD |

Undefined UCD |

Total |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, n (%) | ||||||||||

| Female | 1 (50) | 2 (67) | 40 (61) | 15 (58) | 11 (58) | 4 (44) | 1 (100) | 1 (50) | 75 (59) | |

| Male | 1 (50) | 1 (33) | 26 (39) | 11 (42) | 8 (42) | 5 (56) | 0 (0) | 1 (50) | 53 (41) | |

| Disorder total | 2 (1.5) | 3 (2) | 66 (52) | 26 (20) | 19 (15) | 9 (7) | 1 (1) | 2 (1.5) | 128 (100) | |

| Ages, mean (SD), n |

Average |

|||||||||

| Enrollment (years) | 15.5 (2.1), 2 | 4.3 (6.7), 3 | 12.3 (13.3), 66 | 6.1 (8.2), 26 | 8.8 (10.6), 19 | 12.3 (11.7), 9 | 2.0 (.), 1 | 3.5 (5.0), 2 | 10.2 (11.7), 128 | |

| Diagnosis (days) | 2191.5 (2066.2), 2 | 153.9 (262.2), 3 | 1811.1 (3347.3), 66 | 6.9 (7.7), 26 | 48.4 (128.7), 19 | 1116.9 (955.0), 9 | 334.8 (.), 1 | 92.8 (127.0), 2 | 1062.9 (2561.5), 128 | |

| First Symptoms (days) | 1.0 (.), 1 | 2.0 (1.4), 2 | 3.7 (3.4), 15 | 3.2 (2.2), 22 | 2.9 (1.4), 13 | 43.0 (.), 1 | . (.), 0 | 1.0 (.), 1 | 3.9 (5.9), 55 | |

| Diagnosed (%) |

Total |

|||||||||

| Clinical presentation | 2 (100) | 3 (100) | 56 (86) | 21 (81) | 15 (79) | 7 (78) | 1 (100) | 1 (50) | 106 (83) | |

| Family history | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 8 (12) | 2 (8) | 1 (5) | 2 (22) | 0 (0) | 1 (50) | 14 (11) | |

| Newborn screening | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | 3 (11) | 3 (16) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 7 (6) | |

Number of hyperammonemia events per individual

Depending on their metabolic control, treatment adherence and exposure to catabolic stressors, patients with UCD may experience multiple episodes of acute hyperammonemia.[3] In our current study, patients had less than 1 event per year on average attesting to the overall health of patients enrolled in the longitudinal study (Table II). The majority of patients experienced between 1–3 (65%) and 4–6 (23%) hyperammonemia events since the inception of the study. Fifteen individuals (12%) had ≥ 6 events since the beginning of the study, and for these individuals, the average number of hyperammonemia events/year was 5 (SD=4, min=2, median=3, max=12).

Table II.

UCD subtype acute hyperammonemia events per subject with triggers and treatment disposition. NAGSD – N-acetylglutamate synthase deficiency; CPS1D – carbamoyl phosphate synthetase deficiency; OTCD – ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency; ASD – argininosuccinate synthetase deficiency; ALD – argininosuccinate lysase deficiency; ARGD – arginase deficiency; CITRD – citrin deficiency.

| UCD subtype | NAGSD | CPS1D | OTCD | ASD | ALD | ARGD | CITRD | Undefined UCD | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interim events, n (%) |

Total |

||||||||||||

| 1-3 HA events | 0 (0) | 1 (33) | 45 (68) | 14 (54) | 14 (74) | 7 (78) | 1 (100) | 1 (50) | 83 (65) | ||||

| 4-6 HA events | 1 (50) | 2 (67) | 14 (21) | 9 (35) | 4 (21) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 30 (23) | ||||

| > 6 HA events | 1 (50) | 0 (0) | 7 (11) | 3 (12) | 1 (5) | 2 (22) | 0 (0) | 1 (50) | 15 (12) | ||||

| Total | 2 (1.5) | 3 (2) | 66 (52) | 26 (20) | 19 (15) | 9 (7) | 1 (1) | 2 (1.5) | 128 | ||||

|

Visit type |

|||||||||||||

| Interim event triggers, n (%) |

Total |

Clinic |

ER |

Hospital |

|||||||||

| Infection | 2 (14) | 5 (50) | 48 (23) | 43 (46) | 14 (29) | 18 (64) | 1 (100) | 5 (56) | 136 (33) | 1 (1) | 12 (9) | 121 (89) | |

| Diet | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 37 (18) | 4 (4) | 5 (10) | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 47 (11) | 2 (4) | 5 (11) | 39 (83) | |

| Menses | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 6 (3) | 1 (1) | 1 (2) | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 9 (2) | 1 (11) | 2 (22) | 5 (56) | |

| Medications | 2 (14) | 1 (10) | 23 (11) | 5 (5) | 4 (8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 35 (9) | 3 (9) | 5 (14) | 26 (74) | |

| Stress | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 11 (5) | 4 (4) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (33) | 19 (5) | 3 (16) | 1 (5) | 14 (74) | |

| Pregnancy | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.5) | 0 (0) | 1 (50) | 1 (50) | |

| Other* | 8 (57) | 3 (30) | 71 (34) | 15 (16) | 22 (46) | 6 (21) | 0 (0) | 1 (11) | 126 (31) | 5 (4) | 24 (19) | 97 (77) | |

| Unknown** | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 11 (5) | 3 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 14 (3) | 5 (36) | 2 (14) | 7 (50) | |

Other causes were physician reported and were not classified in any of the other identifiable categories

Unknown causes were physician reported where an identifiable cause was not found

Precipitants of interim events

Acute hyperammonemia may be precipitated by numerous events including, but not limited to, infection, dietary or medication changes, and non-adherence with treatment. Medical providers classified the interim event into a precipitant category (Table II). Consistent with previous reports,[3, 4] the most common identifiable precipitant was Infection (n=136, 33%), followed by Diet (n= 47, 11%). Diet captured nonadherence with prescribed diet, as well as protein and caloric insufficiency. SNOMED codes revealed that upper/lower respiratory tract infections (24%, data not shown) were the most commonly cited type of Infection. Little overlap was seen between the two most common precipitants; only 2% were reported as triggered by both infection and diet. A number of precipitants (31%) were classified by medical providers as not belonging to one of the other identifiable categories (i.e. Other) and a small number (3%) were classified as Unknown.

Change from baseline plasma ammonia

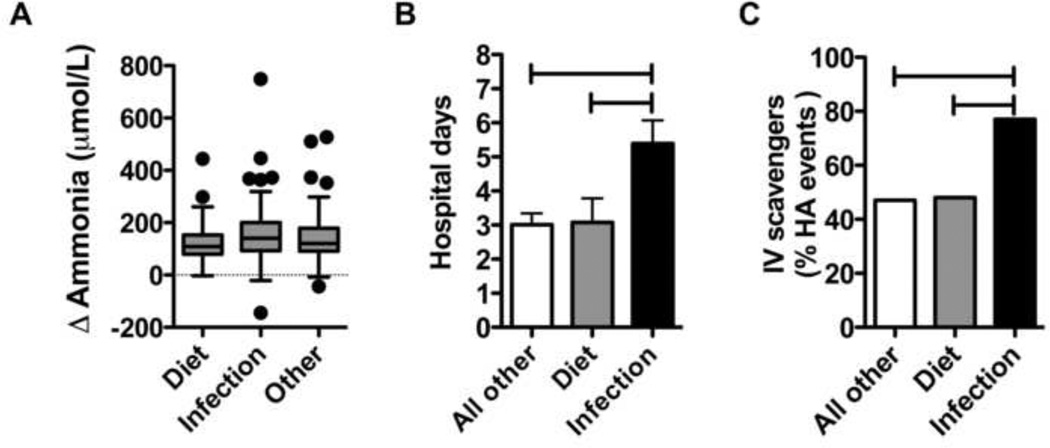

We hypothesized that patients with UCD with infection would experience a greater ammonia burden due to enhanced catabolism from immune activation. To explore this possibility, plasma ammonia samples collected during acute hyperammonemia events were examined for Diet, Infection and Other. Because patients with UCD may have elevated ammonia at baseline, we examined the change from baseline average to presenting plasma ammonia (Figure, A). Data were available for Diet (N=30), Infection (N=99) or Other (N=83). The change in plasma ammonia from baseline was similar amongst the three most common precipitants.

Figure 1.

Infection is associated with markers of morbidity. A) Change in baseline plasma ammonias during acute hyperammonemia in patients with UCD. B) Length of stay for hospitalization due to various acute hyperammonemia precipitants in patients with UCD. C) Use of intravenous (IV) ammonia scavengers for the treatment of acute hyperammonemia due to various precipitants in patients with UCD. Other – indicates precipitants not due to dietary or infectious causes. Hatched bars indicate P < 0.05.

Hospitalization and length of stay for hyperammonemia events

Patients with UCD with acute symptomatic hyperammonemia will present to either hospital-based settings (i.e. the Emergency Department (ED)) or outpatient clinics for clinical care. The UCDC longitudinal database records the ultimate disposition of patients for intermittent hyperammonemia events. Concerning the visit types for acute hyperammonemia, the majority of visits were hospital-based (ED and inpatient hospitalizations) regardless of the precipitant (Table II). Acute hyperammonemia due to Infection or Diet resulted in high rates of hospital inpatient admissions (Table II, 89% and 83% respectively). After adjusting for age at enrollment and UCD subtype, the relative risk for hospitalization for Infection was increased by 15% (P = 0.02). Independent of age and underlying UCD diagnosis, the mean of length of stay (LOS; Figure, B) for Infection was also noted to be approximately 2 days longer LOS than Diet (P=0.03) and all Other (P=0.002). The LOS for Diet and all Other was similar (P=0.90). Because the inability to take oral medications and fluids may account for the increased hospitalization rates and LOS during Infection, we examined the incidence of anorexia or vomiting by precipitant. Overall, there were 231 hyperammonemia events that indicated the reason for hospital visit was anorexia and/or vomiting. This reason occurred in 64% of Infection, 68% of Diet, and 50% of all Other. After controlling for multiple events per subject, Infection was not different from Diet or all Other (p=0.16 and 0.25 respectively).

Management of acute hyperammonemia events

The goals of management of acute hyperammonemia are to minimize protein (nitrogen) intake temporarily, break endogenous protein catabolism by providing sufficient energy to meet metabolic demands, and facilitate alternate routes of ammonia elimination with medications and/or dialysis.[6] Because the majority of patients were hospitalized for acute hyperammonemia, the various medical interventions employed during these admissions were examined (Table III). As expected, the majority of patients received intravenous fluids (79%) as part of their management. Insulin to promote anabolism was used infrequently (3%) and parenteral lipids were used 33% of the time. Regarding ammonia detoxification, oral ammonia scavengers were used somewhat more frequently (64%) than intravenous ammonia scavengers (56%). Combination therapy with oral and intravenous ammonia scavengers was used less often (36%). When considered by precipitating factor (Figure, C), intravenous ammonia scavengers were used more often for Infection (77%), when compared with diet (48%) and all Other (47%). After adjusting for age at enrollment and UCD subtype, the relative risk for the use of intravenous ammonia scavengers for Infection increased by 52% above Diet (P=0.029) and 45% above all Other (P=0.003). There was no difference in the relative risk for the use of intravenous ammonia scavengers between Diet and all Other (P=0.783). Regarding extracorporeal ammonia detoxification (such as dialysis), only 4 study participants required dialysis since the inception of the study. Of note, 2 dialysis episodes occurred in a single patient with citrullinemia on separate occasions.

Table III.

Hospital based treatments for acute hyperammonemia events by UCD subtype. NAGSD – N-acetylglutamate synthase deficiency; CPS1D – carbamoyl phosphate synthetase deficiency; OTCD – ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency; ASD – argininosuccinate synthetase deficiency; ALD – argininosuccinate lysase deficiency; ARGD – arginase deficiency; CITRD – citrin deficiency.

| NAGSD |

CPS1D |

OTCD |

ASD |

ALD |

ARGD |

CITRD |

Undefined UCD |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UCD subtype | Total | |||||||||

| Hospital based interventions, n (%) | ||||||||||

| Fluid Electrolyte Therapy | 13 (93) | 7 (70) | 163 (78) | 77 (83) | 34 (71) | 23 (82) | 1 (100) | 8 (89) | 326 (79) | |

| Insulin | 1 (7) | 1 (10) | 10 (5) | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 14 (3) | |

| Lipids | 8 (57) | 4 (40) | 72 (34) | 22 (24) | 6 (13) | 15 (54) | 1 (100) | 7 (78) | 135 (33) | |

| Oral Ammonia scavengers | 10 (71) | 5 (50) | 138 (66) | 52 (56) | 28 (58) | 22 (79) | 1 (100) | 8 (89) | 264 (64) | |

| I.V. Ammonia scavengers | 11 (79) | 4 (40) | 101 (48) | 59 (63) | 29 (60) | 19 (68) | 1 (100) | 9 (100) | 233 (56) | |

| Oral + I.V. Ammonia scavengers | 8 (57) | 3 (30) | 66 (31) | 32 (34) | 14 (29) | 15 (54) | 1 (100) | 8 (89) | 147 (36) | |

| Dialysis | 1 (7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (1) | |

DISCUSSION

Historically, patients with UCD and other rare biochemical disorders were spread across specialist tertiary hospital centers, making systematic investigation difficult. The Longitudinal Study of the Urea Cycle Disorders Consortium (UCDC) of the Rare Disease Clinical Research Network (RDCRN) was designed to overcome this problem. The network gathers prospective and historical data on the clinical characteristics of this unique patient population and in this case has provided insight into common hyperammonemia triggers associated with UCD. We report a prospective examination of physician reported acute hyperammonemia events in a cohort of patients with UCD involving referral centers for the treatment of UCD in the United States, Canada, and Europe. Because the financial scope of any consortium cannot include every center caring for UCD, the possibility of ascertainment bias and missed patients exists. In addition, as with any database, reporting bias of more severe outcomes cannot be excluded. Despite these limitations, the study represents a significant effort in the study of rare diseases and shows the worth of this type of consortium approach to rare disease.

Acute hyperammonemia events in UCD can be brought on by a number of precipitants including dietary indiscretion, protein/caloric insufficiency, infection, menses, and other stresses (Table II). The pathophysiology of acute hyperammonemia due to catabolic stressors such as infection and dietary insufficiency involves an expanded nitrogen pool from increased whole body protein catabolism. In UCD, this expanded nitrogen pool due to catabolism is fed to a dysfunctional urea cycle. The contribution of whole body catabolism to acute decompensations in inborn errors of protein metabolism is well appreciated by metabolic practitioners but has not been explored by this type of evidence-based approach before.

In our current study, the most common precipitant was a major catabolic stressor: Infection. When compared with diet and all other, causes of infection tends to result in higher rates of hospitalization, with longer hospital stays and a greater need for aggressive nitrogen scavenger therapy. The inability to take food and medications by mouth (anorexia and/or vomiting) did not seem to be associated with infection, and cannot readily explain the increase in the indicators of morbidity seen. The pathophysiology of these markers of increased morbidity may be due in part to immune activation and the actions of inflammatory cytokines.[7] Although dietary insufficiency is generally nitrogen-sparing, infection results in continued loss of nitrogen, despite protein status, leading to greater catabolism.[7] In severe illness up to 20% of body protein stores can be lost over 3 weeks, most of which occurs in the first 10 days,[8] through increases in metabolic rate[9] and the urinary loss of nitrogenous compounds.[7] These unique aspects of infection may be seen in our cohort. Infection displayed a higher relative risk of hospitalization, and LOS was 2 days longer (Figure, B). These data lead us to suggest that although patients with UCD and acute hyperammonemia may have similar biochemical variables (Figure, A) due to various precipitants, they may have more extended periods of illness due to the catabolic actions of immune activation.

In addition to increased catabolism, there may also be interactions between immune activation and the neurologic response to hyperammonemia. The systemic inflammatory response is known to exacerbate the neuropsychological effects of hyperammonemia in patients with cirrhosis.[10] In hepatic encephalopathy, plasma interleukin-6 levels have even been shown to correlate with severity.[11] These interactions between inflammatory cytokines, hyperammonemia and worsening encephalopathy have also been demonstrated in a mouse model of OTC (spf-ash) treated with LPS to induce inflammatory cytokines.[12] The utilization of intravenous ammonia scavengers in the management of acute hyperammonemia is normally recommended for symptomatic hyperammonemic encephalopathy.[13] Although it cannot be determined whether this is a generally applied principle amongst the various providers in this observational study, we postulate that patients with UCD may have an increased incidence of hyperammonemic encephalopathy with Infection. These results imply that there may be a synergistic interaction between inflammatory cytokines and hyperammonemia that may account for increased neurologic morbidity (ie; intravenous ammonia scavenger use; Figure, C) during acute hyperammonemia due to infection in patients with UCD.

In summary, in the UCD cohort presented here, the most common precipitant of acute hyperammonemia was infection. With infection, markers of increased morbidity, including increased rates of hospitalization, longer length of hospitalization and increased utilization of intravenous ammonia scavengers, were found. These data support further exploration regarding whether infectious precipitants might involve distinct pathologic processes. The role of immune activation and cytokines in precipitating and perpetuating acute hyperammonemia is an understudied area; the further characterization of which may serve as new targets of intervention in the management of acute hyperammonemia.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We wish to recognize the efforts of Dr Danuta Krotoski (NIH) for her programmatic support for the UCDC, and Dr Mary Lou Oster-Granite (NIH) for her scientific support. In addition, thanks to Ms Cindy LeMons (Executive Director, National Urea Cycle Disorders Foundation) for providing support and direction. Thanks to Dr Les Biesecker (funded by NIH, serves as an advisor to the Illumina Corp, receives royalties from Genentech Corp, and receives compensation for editorial duties by Wiley-Blackwell Corp) for his guidance and the support of the Physician Scientist Development Program at NHGRI.

Funded by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (U54RR19454 and U54HD061221) and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Office of Rare Diseases Research, and the intramural research program of the NIH (to P.M.). The Urea Cycle Disorders Consortium also is supported by the O'Malley Foundation, the Rotenberg Family Fund, the Dietmar-Hopp Foundation, and the Kettering Fund. The views expressed in written materials or publications do not necessarily reflect the official policies of the Department of Health and Human Services; nor does mention by trade names, commercial practices, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. The Urea Cycle Disorders Consortium is a part of the NIH Rare Diseases Clinical Research Network.

ABBREVIATIONS

- UCD

urea cycle disorder

- NAGS

N-acetylglutamate synthase

- CPS1

carbamoyl phosphate synthetase

- OTC

ornithine transcarbamylase

- ASS1

argininosuccinate synthetase

- ASL

argininosuccinate lysase deficiency

- ARG1

arginase

- NAGSD

N-acetylglutamate synthase deficiency

- CPS1D

carbamoyl phosphate synthetase deficiency

- OTCD

ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency

- ASD

argininosuccinate synthetase deficiency

- ALD

argininosuccinate lysase deficiency

- ARGD

arginase deficiency

- CITRD

citrin deficiency

- RDCRN

Rare Disease Clinical Research Network

- UCDC

Urea Cycle Disorders Consortium

- ED

Emergency Department

- LOS

Length of stay

APPENDIX

Members of UCDC include:

Children’s National Medical Center, Washington, D.C.: Mark L. Batshaw, MD, Mendel Tuchman, MD, Uta Lichter-Konecki, MD, PhD; University Children’s Hospital, Zurich, Switzerland: Matthias R. Baumgartner, MD; University of Minnesota, Amplatz Children’s Hospital, Minneapolis, MN: Susan A. Berry, MD; Mattel Children’s Hospital, University of California at Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA: Stephen Cederbaum, MD, Derek Wong, MD; Mount Sinai Medical Center, New York, NY: George A. Diaz, MD, PhD; The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, ON, Canada: Annette Feigenbaum, MD, Andreas Schulze, MD, PhD; The Children’s Hospital, Aurora, CO: Renata C. Gallagher, MD, PhD; Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, OR: Cary O. Harding, MD; University of Heidelberg, Heidelberg, Germany: Georg F. Hoffmann, MD; Rainbow Babies and Children’s Hospital, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, Cleveland, OH: Douglas S. Kerr, MD, PhD, Shawn E. McCandless, MD; Texas Children’s Hospital, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX: Brendan Lee, MD, PhD; National Urea Cycle Disorders Foundation, Pasedena, CA: Cindy LeMons; Seattle Children’s Hospital, University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, WA: J. Lawrence Merritt II, MD; Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, CT: Margretta R. Seashore, MD; University Children’s Hospital, Zurich, Switzerland: Tamar Stricker, MD; Children’s Hospital Boston, Boston, MA: Susan Waisbren, PhD; Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, PA: Mark Yudkoff, MD.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Neill MA, Aschner J, Barr F, Summar ML. Quantitative RT-PCR comparison of the urea and nitric oxide cycle gene transcripts in adult human tissues. Mol Genet Metab. 2009;97:121–127. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2009.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Summar M, Tuchman M. Proceedings of a consensus conference for the management of patients with urea cycle disorders. J Pediatr. 2001;138:S6–S10. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2001.111831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Summar ML, Dobbelaere D, Brusilow S, Lee B. Diagnosis, symptoms, frequency and mortality of 260 patients with urea cycle disorders from a 21-year, multicentre study of acute hyperammonaemic episodes. Acta Paediatr. 2008;97:1420–1425. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2008.00952.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tuchman M, Lee B, Lichter-Konecki U, Summar ML, Yudkoff M, Cederbaum SD, et al. Cross-sectional multicenter study of patients with urea cycle disorders in the United States. Mol Genet Metab. 2008;94:397–402. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2008.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilson D, Bressani R, Scrimshaw NS. Infection and nutritional status. I. The effect of chicken pox on nitrogen metabolism in children. Am J Clin Nutr. 1961;9:154–158. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/9.2.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singh RH, Rhead WJ, Smith W, Lee B, Sniderman King L, Summar M. Nutritional management of urea cycle disorders. Crit Care Clin. 2005;21:S27–S35. doi: 10.1016/j.ccc.2005.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beisel WR. Metabolic response to infection. Annu Rev Med. 1975;26:9–20. doi: 10.1146/annurev.me.26.020175.000301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bratovanov D. [A new method of determining and analyzing seasonality of acute infectious diseases] Zhurnal mikrobiologii, epidemiologii, i immunobiologii. 1970;47:62–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dubois EF. The Mechanism of Heat Loss and Temperature Regualtion. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press; 1937. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shawcross DL, Davies NA, Williams R, Jalan R. Systemic inflammatory response exacerbates the neuropsychological effects of induced hyperammonemia in cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2004;40:247–254. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2003.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sheron N, Bird G, Goka J, Alexander G, Williams R. Elevated plasma interleukin-6 and increased severity and mortality in alcoholic hepatitis. Clin Exp Immunol. 1991;84:449–453. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marini JC, Broussard SR. Hyperammonemia increases sensitivity to LPS. Mol Genet Metab. 2006;88:131–137. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2005.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Consensus statement from a conference for the management of patients with urea cycle disorders. J Pediatr. 2001;138:S1–S5. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2001.111830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]