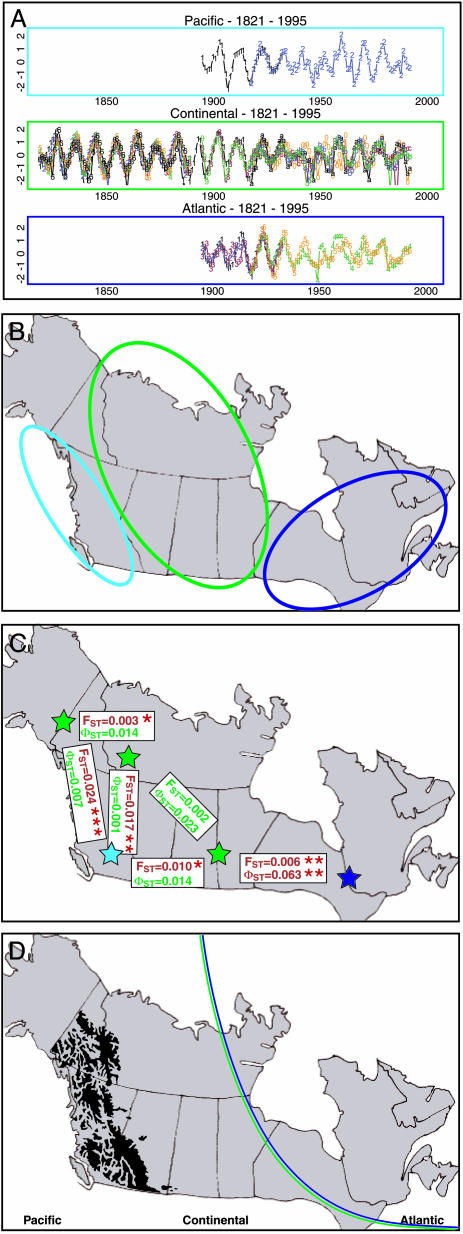

Fig. 1.

Canadian lynx population cycles, climatic zones, and genetic differentiation throughout the boreal forest of North America. (A) The Hudson Bay Company (5) and the Statistics Canada (15) time-series data used by Stenseth et al. (12) to identify the three climatically determined geographic zones. The abundance of lynx is given as log numbers. (B) The three climatically determined geographic zones identified by Stenseth et al. (12): the Pacific (light blue), Continental (green), and Atlantic (dark blue). (C) Rueness et al. (14) recently reported on the large-scale genetic structuring of the Canadian lynx. The geographic center of each of five sampling regions is denoted by a star (following the same color-code as in B): the Atlantic zone (East, n = 46), three regions within the Continental zone (Prairie, n = 48; North, n = 25; and Northwest, n = 40), and the Pacific zone (British Columbia, n = 24). The level of genetic differentiation observed between regions in microsatellites and mitochondrial DNA are given as FST and ΦST values, respectively. ΦST was calculated from haplotype frequencies. Significant differentiation, as shown by the FST/ΦST values, is shown in red, and nonsignificant values are given in green; significance levels are indicated by asterisks: *, 0.05; **, 0.01; and ***, 0.001. (D) The Rocky Mountains, a classic ecological barrier that also corresponds to climatically based differences, characterizes the Canadian subcontinent in the West. In the East, some climatically based, geographically invisible boundary is distinguished. The correlation between the NAO index and local winter and spring temperatures has opposite signs on either side of the double-colored curved line (10).