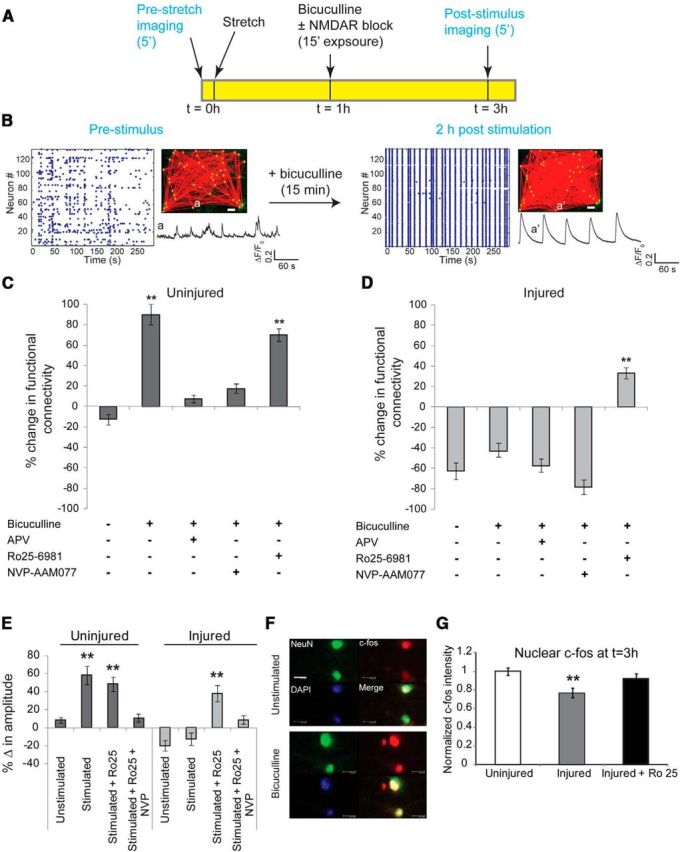

Figure 7.

Activation of GluN2B NMDARs in injured neurons reduces network augmentation induced with synchronization. A, Plasticity through recurrent excitation was induced by blocking inhibitory currents with bicuculline for 15 min. Calcium activity of the network was recorded before injury, the network was subjected to stretch injury and stimulated with bicuculline, and the calcium activity of the same field of view was recorded again 2 h after bicuculline washout. B, In uninjured cultures, a brief period of pharmacological blockade of inhibitory neurons resulted in a persistent increase in synchronized activity and functional connectivity, and an augmentation in single-cell somatic calcium amplitude. Inset, GCaMP5 trace of the same neuron before (a) and 2 h after bicuculline stimulus (a′), illustrating the emergence of rhythmic, large-amplitude calcium oscillations in a′ compared with a. Scale bar, 50 μm. C, We used the percentage change in functional connectivity as one of three metrics to explore the plasticity of the circuit [change in somatic calcium amplitude (E) and nuclear localization of c-fos (G) are the other two metrics]. In uninjured cultures, 15 min of bicuculline treatment led to a significant increase in functional connectivity relative to no stimulus (change in functional connectivity following bicuculline stimulus, 89 ± 9.2%; change in functional connectivity untreated, −12 ± 5.4%; t test, p < 0.001, df = 4). Enhancement in connectivity was abolished by blocking either the activation of NMDARs or specifically targeting GluN2A-containing NMDARs (bicuculline plus APV, 8.2 ± 3.1%; bicuculline plus NVP-AAM077, 17.8 ± 4.7%). D, Injury resulted in a significant decrease in network connectivity (injured, −62 ± 7.3%; uninjured, −12 ± 5.4%; p < 0.001), which could not be restored with bicuculline stimulus (−44 ± 8.5%). However, blocking GluN2B NMDARs during the period induced synchronization led to a significant enhancement in global connectivity (treatment with bicuculline plus Ro25–6981, 37 ± 4.1%; treatment with bicuculline, −44 ± 8.5%; p < 0.001). E, Amplitude of somatic calcium transients increased significantly following washout of bicuculline stimulus in uninjured cultures, which is indicative of enhanced excitability (unstimulated change in amplitude, 8.5 ± 2.2%; change in amplitude following bicuculline stimulus, 58.4 ± 9.1%; p < 0.001). This was dependent on activation of GluN2A-containing NMDARs since exposure to NVP-AAM077 during the period of bicuculline stimulus abolished the change in somatic calcium amplitude (10.2 ± 4.7%). In comparison, the amplitude of somatic calcium transients was significantly lower following injury (−20.2 ± 5.5%) and did not recover following bicuculline treatment (−13.8 ± 6.2%). However, antagonism of GluN2B-containing NMDARs during bicuculline stimulus recovered somatic amplitude to near the levels observed in uninjured cultures (change after bicuculline plus Ro25 stimulus, 37.7 ± 7.7%; change after bicuculline stimulus, −13.8 ± 6.2%; p < 0.001). F, G, We probed the localization of the immediate early transcription factor c-fos and found increased nuclear localization within 2 h of bicuculline treatment in uninjured cultures. Nuclear localization of c-fos was significantly reduced in injured cultures (normalized injured c-fos intensity, 0.77 ± 0.04; normalized uninjured c-fos intensity, 1.0 ± 0.03; p < 0.01) but could be restored by blocking GluN2B-containing NMDARs during the period of bicuculline stimulation (0.91 ± 0.05). Scale bar, 100 μm.