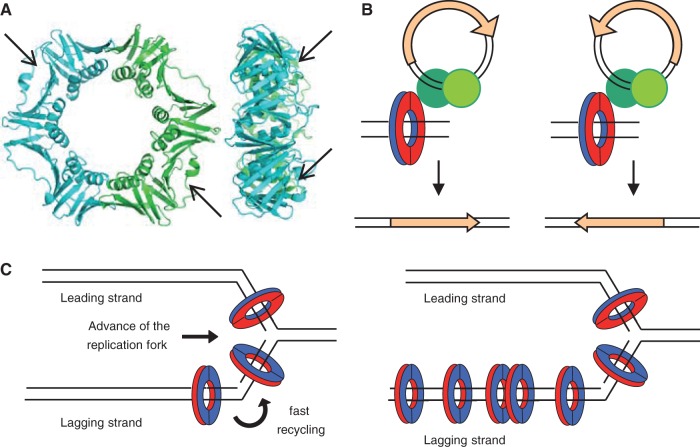

Fig. 4.—

Structural and functional asymmetries contributing to biased orientation of ISs in chromosomes. (A) Structure of Escherichia coli β, front (left) and side (right) views (PDB: 2POL). Arrows indicate the hydrophobic pockets on the surface of each monomer of β that are the sites of interaction of all β partners studied and of all the transposase peptides described in this study. (B) The asymmetry of transpososomes (green circles) in their interaction with β could determine the orientation of the transposase gene (orange arrow). The interaction “face” of β is colored red, the other blue. (C) Models of replisomes of E. coli and Bacillus subtilis. β is loaded on DNA by the γ-complex, which for leading strand synthesis positions β facing the direction of movement of the replication fork and in the opposite orientation in the lagging strand. On the left panel, the E. coli the replisome shows a homogeneous concentration of β associated with the synthesis of both strands (Reyes-Lamothe et al. 2010). On the right panel, β accumulates in “clamp zones” as the B. subtilis replisome progresses, possibly due to slow recycling after Okazaki fragment synthesis, creating an asymmetry in the distribution of β associated to the synthesis of leading and lagging strands (Su'etsugu and Errington 2011).