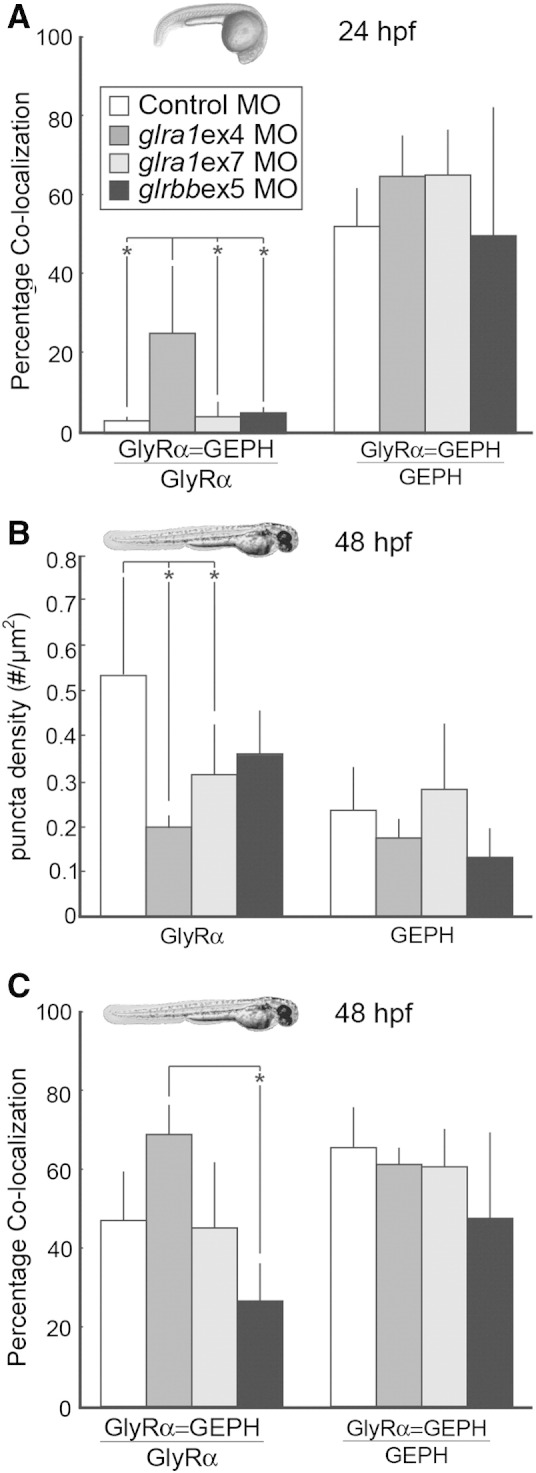

Fig. 8.

GlyR densities are significantly reduced in glra1 morphants, while the percentage of glycine receptors that co-localize with gephyrin is reduced in glrbb morphants. A. After GlyR α and gephyrin (GEPH) puncta were found using a customized MatLab program, co-localization was calculated in control (n = 7), glra1 (ex4 n = 6; ex7 n = 3), and glrbb (n = 3) 24 hpf morphants in two ways: either as the fraction of GlyRs that co-localized with GEPH (ANOVA indicated a significant effect of morpholino injected on percent of GlyR α puncta that co-localizes with GEPH [F(3,15) = 6.55, p = 0.005]), or as the fraction of GEPH that colocalized with GlyR (ANOVA indicated no significant effect of morpholino injected [F(3,15) = 1.27, p = 0.32]). Bar graphs show means with error bars indicating standard deviation for all groups. Post hoc Bonferroni-corrected Student's t-tests compared all means and demonstrated that at p < 0.05 (* in graph), only glra1MOex4 had significantly more co-localization than control, glra1MOex7, and glrbbMOex5 morpholino treatments. Surprisingly fewer GlyR α puncta co-localize with GEPH at 24 hpf than at 48 hpf, C, while the proportion of GEPH colocalizing with GlyR puncta remains fairly constant. The proportion of GlyR α puncta that co-localize with GEPH is greatest in the glra1ex4 morphants that lack the GlyR α epitope, supporting the conclusion that in glra1 morphants, residual co-localization reflects synaptic staining of GlyR α2, α3, or α4a. B. GlyR and GEPH densities were calculated in control (n = 6), glra1 (ex4 n = 3; ex7 n = 7), and glrbb (n = 5) morphants at 48 hpf. Bar graphs show means with error bars indicating standard deviation. ANOVA indicates a significant effect of the mopholino injected on GlyR puncta density [F(3, 16) = 4.39, p = 0.02] but not on GEPH puncta [F(3,16) = 2.03, p = 0.15]. Post hoc Bonferroni-corrected Student's t-tests compared all means and demonstrated that at p < 0.05 (* in graph), only glra1MOex4 and glra1MOex7 were significantly reduced control morpholino treatments, although glrbbMOex5 treatments also trends in the same direction. C. Co-localization between GlyR and GEPH was quantified in control (n = 5), glra1(ex4 n = 3; ex7 n = 6), and glrbb (n = 4) 48 hpf larva in two ways: either as the fraction of GlyRs that co-localized with GEPH (ANOVA indicated a significant effect of morpholino injected on percent of GlyR α puncta that co-localizes with GEPH [F(3,16) = 5.89, p = 0.007]), or as the fraction of GEPH that colocalized with GlyR (ANOVA indicated no significant effect of morpholino injected [F(3,14) = 1.56, p = 0.24]). Bar graphs show means with error bars indicating standard deviation for all groups. Post hoc Bonferroni-corrected Student's t-tests compared all means and demonstrated that at p < 0.05 (* in graph), only the glrbbMOex5 treatment had significantly less co-localization than the glra1MOex4 treatment. In glra1MOex7 morphants, many peri-nuclear GlyR puncta fail to co-localize with GEPH. These likely represent GlyRs that are trapped intracellularly. Differences between glra1MOex4 and glra1MOex7 are likely explained by fewer intracellular GlyRs being recognized by mAb4a in glra1MOex4, since this antibody targets amino acids 96–105 that are lacking in glra1ex4 morphants. Therefore, residual staining in glra1MOex4 morphants is likely to reflect other GlyR α subunits, e.g. 2, 3, or 4a.