Abstract

Objective

Risk factors for breast, colorectal, and lung cancer are known to be more common among lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) individuals, suggesting they may be more likely to develop these cancers. Our objective was to determine differences in cancer incidence by sexual orientation, using sexual orientation data aggregated at the county level.

Methods

Data on cancer incidence were obtained from the California Cancer Registry and data on sexual orientation were obtained from the California Health Interview Survey, from which a measure of age-specific LGB population density by county was calculated. Using multivariable Poisson regression models, the association between the age–race-stratified incident rate of breast, lung and colorectal cancer in each county and LGB population density was examined, with race, age group and poverty as covariates.

Results

Among men, bisexual population density was associated with lower incidence of lung cancer and with higher incidence of colorectal cancer. Among women, lesbian population density was associated with lower incidence of lung and colorectal cancer and with higher incidence of breast cancer; bisexual population density was associated with higher incidence of lung and colorectal cancer and with lower incidence of breast cancer.

Conclusions

These study findings clearly document links between county-level LGB population density and cancer incidence, illuminating an important public health disparity.

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Using sexual orientation population data aggregated at the county-level findings helps identify associations between cancer incidence and sexual minority population density.

These county-level differences in cancer incidence suggest a need for public health planning, which was previously unavailable.

Because cancer registries do not document sexual orientation, determining whether disparities exist in cancer incidence due to sexual orientation is not possible otherwise.

Because data are at the county level, it is not possible to link sexual minority status to cancer risk at the level of the individual.

The study's findings have the inherent limitations of the ecological study design.

Introduction

Lung, colorectal and female breast cancer are three of the most commonly diagnosed cancers in the USA, with incidence rates of 79.5, 51.6 and 121.9 per 100 000, respectively, in 2008.1 Smoking and alcohol use are well-known risk factors for all three of these cancers; overweight and/or obesity has been linked to risk of female breast cancer and colorectal cancer.2 In addition, nulliparity is associated with increased risk of female breast cancer.

Research also indicates that the prevalence of these well-known risk factors is generally higher among sexual minority individuals—that is, lesbian, gay and bisexual (LGB) individuals. Smoking is more common among sexual minorities, both men and women, than among their heterosexual counterparts.3–8 Further, in 2007, the President's Cancer Panel found that sexual minority youths smoke at rates as high as those of adults, and tend to start smoking at a younger age than heterosexual youths.6 Sexual minority women are more likely than heterosexual women to drink alcohol5 8–12 and to be overweight or obese.10 13–16 In contrast, gay men's alcohol use has not been shown to differ from that of heterosexual men,12 and gay men are less likely than heterosexual men to be overweight or obese.17 Finally, sexual minority women have higher rates of nulliparity than heterosexual women.10 13 14 18–20

Because cancer registries do not collect information on the sexual orientation of individuals diagnosed with cancer, it cannot be readily determined from SEER or state registry data whether cancer is more prevalent among individuals with a sexual minority orientation. To overcome this lack of data on cancer disparities by sexual orientation, three previous studies used county-level ecological analyses to relate breast, lung and colorectal cancer incidence to greater sexual minority population density.21–23 Previously, we used SEER registry data and US Census data on individuals living in same-sex partnered households as a proxy measure for sexual minority orientation. These ecological studies concluded that greater female sexual minority density (SMD) in a county is associated with greater incidence of breast and colorectal cancer,21 22 while there was a negative relationship between female sexual minority population density and lung cancer incidence.23 Greater density of sexual minority men was associated with higher incidence of lung and colorectal cancer.22 23

While US Census data on same-sex households are a well-established proxy for sexual orientation, these data also have known limitations. From available Census data, we can enumerate households led by same-sex adults, but this surely represents an undercount since we capture only sexual minority individuals who live with a same-sex partner, thereby excluding sexual minority individuals who are living alone or with non-partners. Further, we do not know how many members of a same-sex partnered household identify as LGB. In particular, it is impossible to assess lesbians separately from bisexual women or to assess gay men separately from bisexual men. This is an important limitation, because studies that analysed lesbian women separately from bisexual women concluded that bisexuals fare worse on some health indicators than both heterosexual and lesbian women.24–27

To address the limitations of US Census data, the present study traded a national scope for an improved measure of SMD. We used statewide population-based data on sexual minority identity (gay, lesbian or bisexual) to estimate its relationship to colorectal cancer, lung cancer and female breast cancer incidence.

Materials and methods

The Institutional Review Board deemed this study exempt from protocol review. Data for this research project were taken from the California Health Interview Survey (CHIS), the largest state health survey conducted in the USA. The CHIS employs a two-stage geographically stratified random-digit-dial sample of households, surveying one randomly selected adult from each sampled household. The survey is administered in multiple languages, resulting in a large multiethnic/multiracial sample that accurately represents the California population living in households. The CHIS response rate shows no significant non-response bias by demographic characteristics such as age, sex, income, education or employment status28; however, owing to the absence of a sampling frame, non-response by sexual orientation has not been evaluated. More detailed information about the survey methodology can be obtained from the website: http://www.chis.ucla.edu/. The CHIS collects information biennially, including data on sexual orientation. To ascertain sexual orientation, respondents were asked about their sexual identity, with response choices of heterosexual, LGB along with celibate or other, while recording refusals and do not know responses. We combined 4 years of data, using the adult CHIS surveys from 2001, 2003, 2005 and 2007 to increase the numbers of individuals who report a sexual minority orientation, defined as gay, lesbian or bisexual.

Data on cancer incidence were taken from the California Cancer Registry, which records all cancer cases to monitor the occurrence of cancer among Californians. We chose the cancer data for the years 2001–2008 because these years cover the same time frame as the CHIS sexual minority data. We further restricted our data to men and women aged 18–84, because we focused on adult cancers and also because this is the age range for which the CHIS had sexual orientation data available.

Because there are differences in cancer incidence by age and race, we used the population data from Census 2000 since it has age-specific and race-specific population data available for all the 58 counties in California. From the Census, we also obtained county-level data on poverty, another important confounder of cancer incidence.

Measures

Counts of breast, lung and colorectal cancer incidence were classified into 1 of 11 age categories and four race/ethnicity groups. The 11 age categories were 18–24, 25–29, 30–34, 35–39, 40–44, 45–49, 50–54, 55–59, 60–64, 65–69 and 70–84, while race and ethnicity consisted of (1) non-Hispanic white, (2) Hispanic, (3) Asian/Pacific Islander and (4) other race/ethnicity. The group of other race/ethnicity combines non-Hispanic blacks (6.79% of cancers), other/unknown race/ethnicity (0.73% of cancers) and non-Hispanic American Indian (0.14% of cancers). We calculated each cancer incidence rate using the total female and male population between ages 18 and 84 in each county using the Census data.

We adjusted for poverty level in our analyses, with poverty level being defined as the percentage of the population living under the Federal poverty level, which has been found to be the most consistent, easily interpretable variable which accurately measures socioeconomic disparities in health outcomes.29 30

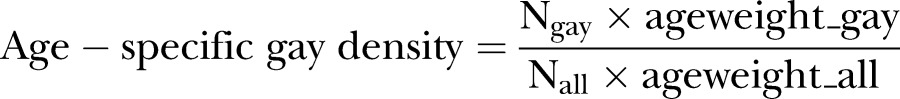

Our main independent variable is derived from the CHIS data on participants’ sexual orientation. We are using these data aggregated at the county level and call this aggregate variable ‘SMD’ to express variation in the density of sexual minority populations in a county. To make these data age specific, we obtained the distribution of sexual minorities, defined as LGBs, across different age groups, and combined this information with the county-level SMD. Specifically, we obtained the weighted percentage of gay men in a specific age group (denoted as ageweight_gay), using the age information on all gay men in the 58 California counties. Then we obtained the weighted percentage of all men in the specific age group (denoted as ageweight_all), using the age information on all participants in the 58 California counties. Finally, we obtained the count of all adult gay men (Ngay) and the count of all adult men (Nall) in the specific age group, and computed the age-specific gay density as:

|

The age-specific lesbian and bisexual population density was computed in a similar way, and we considered bisexual men and women as distinct categories for analyses.

Regression diagnostics indicated that the Los Angeles County, white race, age 70–84, data point was a potentially influential point. We refit all regression models excluding this data point to ensure that our findings are not predominantly dependent on a single observation. Model fit did not improve substantially with the exclusion, and more importantly, changes in estimates of associations between the density measures and cancer incidence were small and well within the SEs. Therefore, we report all regression results with no data exclusions.

Statistical analysis

We used descriptive statistics to summarise our outcomes, cancer incidence and our main independent variables, that is, LGB population density, for all 58 California counties. We assessed county-level association between lesbian/gay/bisexual density (LGBD) and cancer incidence rates using multivariable Poisson regression models with the age–race-stratified count of incident cases in each county as the dependent variable, and the LGBD, race, age group and US Census per cent in poverty as covariates. We fitted models that considered L/G and B together because the correlation between lesbian/gay density and bisexual density was low—0.36 (p<0.0001) for women and 0.15 (p<0.0001) for men and because our primary parameter estimates remained essentially unchanged when we fitted the two density measures separately All model selections were based on the goodness of fit of the models assessed by the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and residual diagnostics plots. SAS PROC GENMOD was used to fit the models, with the offset term as the logarithm of the US Census age–race-stratified total adult population in the county. The incidence rate ratio (IRR) was presented as the measure of the effect of each predictor, along with its 95% CI and p value. The validity of the assumptions and the goodness of fit of the assumed models were assessed by residual diagnostic plots and goodness-of-fit statistics such as the Deviance statistic. All analyses were carried out in SAS V.9.2 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, North Carolina, USA).

Results

There is considerable variation in the SMD measures by county. Across 58 California counties, the lesbian density measure ranges from 0 to 3.05 (median=0.49; mean=0.66; SD=0.78) and the bisexual density measure from 0 to 4.16 (median=1.24; mean=1.16; SD=0.97). Gay and bisexual male density measures respectively range from 0 to 16.02 (median=0.80; mean=1.10; SD=2.19) and from 0 to 4.07 (median=0.44; mean=0.60; SD=0.76).

Sexual orientation, demographics and cancer incidence among males

Controlling for race/ethnicity and poverty, gay density was not associated with county-level lung cancer incidence among men (table 1), although bisexual density was associated with an 8.4% decrease in lung cancer incidence (IRR=0.916, p<0.0001). There were expected significant associations between self-reported race/ethnic category and incidence, and a positive association between poverty and lung cancer incidence.

Table 1.

Multivariate Poisson regression analysis for male lung cancer*

| Predictors | Regression coefficient estimate | IRR | 95% CI of IRR | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gay density | 0.0004 | 1.0004 | 0.995 to 1.006 | 0.88 |

| Bisexual density | −0.0875 | 0.916 | 0.897 to 0.936 | <0.0001 |

| Hispanic vs non-Hispanic white | −0.4243 | 0.654 | 0.637 to 0.672 | <0.0001 |

| Asian/PI vs non-Hispanic white | −0.0674 | 0.935 | 0.910 to 0.960 | <0.0001 |

| Other vs non-Hispanic white | −0.0537 | 1.055 | 1.025 to 1.086 | 0.0003 |

| Poverty | 0.0134 | 1.014 | 1.012 to 1.015 | <0.0001 |

*Results also adjusted for age.

IRR, incidence rate ratio; PI, Pacific Islander.

Controlling for race/ethnicity and poverty, gay density was not significantly associated with colorectal cancer incidence (table 2), but bisexual density among men was associated with a 2.7% increase in incidence of colorectal cancer (IRR=1.027, p=0.02).

Table 2.

Multivariate Poisson regression analysis for male colorectal cancer*

| Predictors | Regression coefficient estimate | IRR | 95% CI of IRR | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gay density | −0.0020 | 0.998 | 0.993 to 1.003 | 0.45 |

| Bisexual density | 0.0262 | 1.027 | 1.004 to 1.050 | 0.02 |

| Hispanic vs non-Hispanic white | 0.0411 | 1.042 | 1.018 to 1.067 | 0.0006 |

| Asian/PI vs non-Hispanic white | 0.1056 | 1.111 | 1.082 to 1.142 | <0.0001 |

| Other vs non-Hispanic white | 0.0942 | 1.099 | 1.065 to 1.134 | <0.0001 |

| Poverty | 0.0038 | 1.004 | 1.002 to 1.006 | <0.0001 |

*Results also adjusted for age.

IRR, incidence rate ratio; PI, Pacific Islander.

Sexual orientation, demographics and cancer incidence among females

Controlling for race/ethnicity and poverty, each one-unit increase in lesbian density was associated with a 5.1% decrease in incidence of lung cancer (IRR=0.949, p<0.0001; table 3), whereas each one-unit increase in bisexual density was associated with an 11.3% increase (IRR=1.113, p<0.0001). There were significant negative associations between female lung cancer incidence and Hispanic, Asian/Pacific Islander and other races. There was no significant association between female lung cancer incidence and poverty.

Table 3.

Multivariate Poisson regression analysis for female lung cancer*

| Predictors | Regression coefficient estimate | IRR | 95% CI of IRR | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lesbian density | −0.0521 | 0.949 | 0.928 to 0.971 | <0.0001 |

| Bisexual density | 0.1067 | 1.113 | 1.078 to 1.149 | <0.0001 |

| Hispanic vs non-Hispanic white | −0.7012 | 0.496 | 0.482 to 0.511 | <0.0001 |

| Asian/PI vs non-Hispanic white | −0.5264 | 0.591 | 0.573 to 0.609 | <0.0001 |

| Other vs non-Hispanic white | −0.1527 | 0.858 | 0.832 to 0.885 | <0.0001 |

| Poverty | 0.0013 | 1.001 | 0.999 to 1.003 | 0.18 |

*Results also adjusted for age.

IRR, incidence rate ratio; PI, Pacific Islander.

Controlling for race/ethnicity and poverty, each one-unit increase in lesbian density was associated with a 2.9% decrease in the incidence of colorectal cancer among women (IRR=0.971, p=0.0095; table 4); bisexual density was not associated with incidence of colorectal cancer among women. Hispanic ethnicity had a significant negative association, whereas Asian/Pacific Islander and other race had a significant positive association with incidence of colorectal cancer among women. Poverty was not significantly associated with incidence of colorectal cancer in women.

Table 4.

Multivariate Poisson regression analysis for female colorectal cancer*

| Predictors | Regression coefficient estimate | IRR | 95% CI of IRR | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lesbian density | −0.0290 | 0.971 | 0.950 to 0.993 | 0.0095 |

| Bisexual density | 0.0268 | 1.027 | 0.994 to 1.062 | 0.1105 |

| Hispanic vs non-Hispanic white | −0.0670 | 0.932 | 0.909 to 0.957 | <0.0001 |

| Asian/PI vs non-Hispanic white | 0.1133 | 1.120 | 1.090 to 1.151 | <0.0001 |

| Other vs non-Hispanic white | 0.1616 | 1.175 | 1.139 to 1.213 | <0.0001 |

| Poverty | 0.0020 | 1.002 | 1.000 to 1.004 | 0.056 |

*Results also adjusted for age.

IRR, incidence rate ratio; PI, Pacific Islander.

Controlling for race/ethnicity and poverty, each one-unit increase in lesbian density was significantly associated with a 2.3% increase, and bisexual density with a 3.2% decrease, in incidence of female breast cancer (lesbian: IRR=1.023, p<0.0001; bisexual: IRR=0.968, p<0.0001; table 5). Hispanic, Asian/Pacific Islander and other race/ethnicity had significant negative associations with breast cancer incidence. Poverty was modestly but significantly associated with decreased breast cancer incidence.

Table 5.

Multivariate Poisson regression analysis for female breast cancer*

| Predictors | Regression coefficient estimate | IRR | 95% CI of IRR | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lesbian density | 0.0225 | 1.023 | 1.014 to 1.031 | <0.0001 |

| Bisexual density | −0.0328 | 0.968 | 0.955 to 0.981 | <0.0001 |

| Hispanic vs non-Hispanic white | −0.2691 | 0.764 | 0.755 to 0.774 | <0.0001 |

| Asian/PI vs non-Hispanic white | −0.1790 | 0.836 | 0.824 to 0.848 | <0.0001 |

| Other vs non-Hispanic white | −0.2533 | 0.776 | 0.763 to 0.790 | <0.0001 |

| Poverty | −0.0106 | 0.990 | 0.989 to 0.991 | <0.0001 |

*Results also adjusted for age.

IRR, incidence rate ratio; PI, Pacific Islander.

Discussion

This study's findings document disparities in the age-adjusted incidence of three cancers across the counties of California: disparities that are associated with the density of sexual minorities, controlling for race/ethnicity and the prevalence of poverty. Our outcome measure provides effect estimates in the form of the percentage change in cancer incidence per one-unit increase in sexual minority population density.

Among men, bisexual density (but not gay density) was significantly associated with cancer incidence. Specifically, bisexual density was associated with lower incidence of lung cancer and less strongly with higher incidence of colorectal cancer. Among women, lesbian density (but not bisexual density) was significantly associated with colorectal cancer. Lesbian and bisexual density was significantly associated with female breast and lung cancer incidence. However, these two associations were opposite in direction: lesbian density was associated with lower incidence of lung cancer and higher incidence of breast cancer; bisexual density was associated with higher incidence of lung cancer and lower incidence of breast cancer. For each cancer outcome that we studied, Los Angeles county, white race and age 70–84 emerged as an influential outlying data point. Because Los Angeles county is also the most populous county in California, we carefully considered issues around the robustness of our results. We conducted a sensitivity analysis, which suggests our findings are not overly dependent on this single data point, lending strength to the overall reliability of our findings.

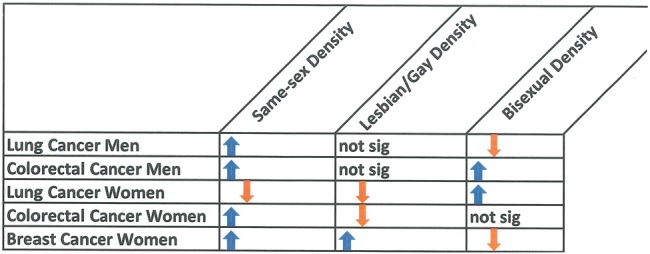

The differences between results for lesbian/gay density and bisexual density are consistent with an increasing understanding among sexual orientation researchers that—after years of combining lesbian/gay and bisexual individuals into one group due to small sample sizes—differences between these groups come to the forefront once they are separated.8 31–34 These findings reflect methodological improvements on our previous studies of SMD and cancer incidence21–23: those analyses used US Census data on whether a respondent lived in a same-sex partnered household, whereas data for the current analysis rest on self-reported sexual identity from the CHIS, as described above, and distinguish between gay/lesbian and bisexual respondents. A comparison of findings from our other analyses to those of this study shows a mix of consistencies and inconsistencies (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Comparing results for different sexual minority density measures. Not sig, not significant.

Using SEER data, colorectal cancer incidence was significantly and positively associated with both sexual minority men density and sexual minority women density22; that finding aligns with this study's finding for male and female bisexual density and colorectal cancer, but is inconsistent with the present findings for gay and lesbian density. In the present study, we identified among men no association between gay density and lung cancer, and a negative association between bisexual density and lung cancer; this conflicts with our finding of a positive association for sexual minority men density and lung cancer using a different dataset.23 For female lung cancer, our current findings for lesbian women are consistent with our previous finding of a significant negative association between lung cancer and sexual minority women density,23 although the present study also found a positive association with bisexual density specifically. Finally, findings for breast cancer show some consistency: in the present study, lesbian density has a significant positive association with breast cancer incidence, confirming our earlier findings,21 although the present study also identified a negative association with bisexual density.

A number of factors are likely to contribute to differences between results of earlier Census-based analyses, which did not distinguish between gays/lesbians and bisexuals, and those of the present study, which relied on self-reported sexual identity. The Census data on same-sex partnered households are probably better indicators of gay and lesbian than bisexual individuals, given the data showing that the majority of partnered gay and lesbian individuals have a same-sex partner, whereas partnered bisexual individuals are more likely to be in heterosexual relationships.34 The present study's ability to distinguish lesbian/gay density from bisexual density is an improvement in the ascertainment of sexual minority orientation. This most likely accounts for identifying effects that are opposite in direction, as for example, lesbian density's association with a 5.1% decrease and bisexual density's 11.3% increase in lung cancer incidence. Another factor may be the relative size of the subgroups within the LGB adult population: among women, more identify as bisexual than lesbian, whereas among men, more identify as gay.35 Differences in the findings of this study compared to the earlier studies are also attributable to the difference in geographical scope. The present study is limited to cancer incidence in California, while the previous SEER-based study was representative of the USA. Moreover, the earlier studies used a roughly fourfold larger sample (215 counties compared to the present study's 58 counties); thus, in the current study, we had lower statistical power to detect associations. Both ecological studies failed to achieve a complete ascertainment of sexual minority status, albeit for different reasons; the Census-based studies relied on an enumeration of same-sex partnered individuals, while the present study relied on population estimates of sexual identity. Methodological differences aside, there may be real-world differences between California and the country as a whole in connections between SMD and cancer incidence.

This study has the inherent limitations of the ecological study design. In particular, because data are at the county level, it is not possible to link sexual minority status to cancer risk at the level of the individual. Thus, our study findings clearly describe links between county-level density measures and cancer incidence and should not be interpreted as evidence of an association between individual sexual orientation and cancer incidence. A finer scale—for example, at the level of the census tract—may provide more insight into patterns of SMD and cancer incidence, but it is not yet clear what is the most appropriate geographic scale for such studies.

Despite these limitations, and some inconsistencies between the work described here and in our previous analyses,21–23 a particular strength is that these ecological analyses identified the existence of sexual orientation disparities in cancer incidence at the county level, while the consideration of gender minority density was outside the scope of this study. Future studies are needed to identify ecological causes for the disparity in cancer incidence, which are most likely complex, possibly examining county-level factors related to sexual minorities’ access to the healthcare system and quality of care delivery. So far, a contextual understanding of sexual minorities’ cancer incidence is lacking as well as knowledge about the county or neighbourhood effects on sexual minority populations’ health and health behaviours more broadly. We suggest that the consistency with which our ecological analyses identified disparities in cancer incidence is an opportunity for public health policy interventions, which are larger in scale, considering county-level programmes, rather than interventions that focus on individual behaviour change. We hope additional research can be performed to identify county-level factors, such as density of healthcare, the equality of healthcare for sexual minorities, along with other known cancer prevention behaviours, such as smoking, that may affect cancer incidence.

While increasing attention is being paid to the collection of sexual orientation data in the context of state or federal health surveys, from which one can derive differences in the prevalence of health risk factors, at present, there is no systematic surveillance of sexual or gender minorities with respect to cancer. Owing to this omission, our goal has been to examine the question about cancer disparities by sexual orientation using ecological analyses. Similarly, motivated by a lack of individual-level data on sexual orientation and cancer, a recent study analysed data on women in same sex and opposite sex relationships, that is, a proxy for sexual orientation, concluding that women in same-sex relationships have greater risk for breast cancer-related mortality.36 So far, evidence is accumulating that sexual minorities carry a disproportionate burden of cancer; therefore, calls are growing louder that cancer registries and SEER ought to collect sexual orientation data to adequately fulfil their mission of monitoring population health, which has to include sexual minority populations as well.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: UB originated the study and interpreted the findings. XM conducted the analyses and helped to interpret the findings. NIM led the writing. AO used his statistical expertise to direct the analysis and helped to interpret the findings. All authors contributed in significant ways to the final version of the article by discussing earlier drafts, reviewing and revising the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health (grant number 1 R03 CA153063-01).

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Boston University Institutional Review Board (IRB).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.U.S. Cancer Statistics Working Group United States Cancer Statistics: 1999–2008 incidence and mortality web-based report. Atlanta, GA: Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and National Cancer Institute, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 2.IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Cancer Preventive Strategies Weight control and physical activity. Lyon, France: IARC Press, 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ryan H, Wortley PM, Easton A, et al. Smoking among lesbians, gays, and bisexuals: a review of the literature. Am J Prev Med 2001;21:142–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tang H, Greenwood GL, Cowling DW, et al. Cigarette smoking among lesbians, gays, and bisexuals: how serious a problem? (United States). Cancer Causes Control 2004;15:797–803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burgard SA, Cochran SD, Mays VM. Alcohol and tobacco use patterns among heterosexually and homosexually experienced California women. Drug Alcohol Depend 2005;77:61–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.The President's Cancer Panel Promoting healthy lifestyles: policy, program, and personal recommendations for reducing cancer risk. Annual Report 2006–2007 Bethesda, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee JG, Griffin GK, Melvin CL. Tobacco use among sexual minorities in the USA, 1987 to May 2007: a systematic review. Tob Control 2009;18:275–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duplicate Adult health behaviors in different age cohorts by sexual orientation. Am J Public Health 2012;102:292–300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cochran SD, Keenan C, Schober C, et al. Estimates of alcohol use and clinical treatment needs among homosexually active men and women in the U.S. population. J Consult Clin Psychol 2000;68:1062–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cochran SD, Mays VM, Bowen D, et al. Cancer-related risk indicators and preventive screening behaviors among lesbians and bisexual women. Am J Public Health 2001;91:591–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gilman SE, Cochran SD, Mays VM, et al. Risk of psychiatric disorders among individuals reporting same-sex sexual partners in the National Comorbidity Survey. Am J Public Health 2001;91:933–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Drabble L, Midanik LT, Trocki K. Reports of alcohol consumption and alcohol-related problems among homosexual, bisexual and heterosexual respondents: results from the 2000 National Alcohol Survey. J Stud Alcohol 2005;66:111–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Valanis BG, Bowen DJ, Bassford T, et al. Sexual orientation and health: comparisons in the women's health initiative sample. Arch Fam Med 2000;9:843–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Case P, Bryn Austin S, Hunter DJ, et al. Sexual orientation, health risk factors, and physical functioning in the Nurses’ Health Study II. J Womens Health 2004;13:1033–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boehmer U, Bowen DJ. Examining factors linked to overweight and obesity in women of different sexual orientations. Prev Med 2009;48:357–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boehmer U, Bowen DJ, Bauer GR. Overweight and obesity in sexual minority women: evidence from population-based data. Am J Public Health 2007;97:1134–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deputy NP, Boehmer U. Determinants of body weight among men of different sexual orientation. Prev Med 2010;51:129–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rankow EJ, Tessaro I. Mammography and risk factors for breast cancer in lesbian and bisexual women. Am J Health Behav 1998;22:403–10 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kavanaugh-Lynch MHE, White E, Daling JR, et al. Correlates of lesbian sexual orientation and the risk of breast cancer. J Gay Lesbian Med Assoc 2002;6:91–5 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dibble SL, Roberts SA, Nussey B. Comparing breast cancer risk between lesbians and their heterosexual sisters. Womens Health Issues 2004;14:60–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boehmer U, Ozonoff A, Timm A. County-level association of sexual minority density with breast cancer incidence: results from an ecological study. Sex Res Soc Policy 2011;8:139–45 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boehmer U, Ozonoff A, Miao X. An ecological analysis of colorectal cancer incidence and mortality: differences by sexual orientation. BMC Cancer 2011;11:400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boehmer U, Ozonoff A, Miao X. An ecological approach to examine lung cancer disparities due to sexual orientation. Public Health 2012;126:605–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Steele LS, Ross LE, Dobinson C, et al. Women's sexual orientation and health: results from a Canadian population-based survey. Women Health 2009;49:353–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brewster KL, Tillman KH. Sexual orientation and substance use among adolescents and young adults. Am J Public Health 2012;102:1168–76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tjepkema M. Health care use among gay, lesbian and bisexual Canadians. Health Rep 2008;19:53–64 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kertzner RM, Meyer IH, Frost DM, et al. Social and psychological well-being in lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals: the effects of race, gender, age, and sexual identity. Am J Orthopsychiatry 2009;79:500–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee S, Brown ER, Grant D, et al. Exploring nonresponse bias in a health survey using neighborhood characteristics. Am J Public Health 2009;99:1811–17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Singh G, Miller B, Hankey B, et al. Area socioeconomic variations in U.S. cancer incidence, mortality, stage, treatment, and survival, 1975–1999. NCI Cancer Surveillance Monograph Series. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute, 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krieger N, Chen JT, Waterman PD, et al. Painting a truer picture of US socioeconomic and racial/ethnic health inequalities: the Public Health Disparities Geocoding Project. Am J Public Health 2005;95:312–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Institute of Medicine The health of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people: building a foundation for better understanding. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2011 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bauer GR, Jairam JA. Are lesbians really women who have sex with women (WSW)? Methodological concerns in measuring sexual orientation in health research. Women Health 2008;48:383–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Kim H-J, Barkan SE, et al. Disparities in health-related quality of life: a comparison of lesbians and bisexual women. Am J Public Health 2010;100:2255–61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Herek G, Norton A, Allen T, et al. Demographic, psychological, and social characteristics of self-identified lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in a US probability sample. Sex Res Soc Policy 2010;7:176–200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Greenberg JA. Health care issues affecting people with an intersex condition or DSD: sex or disability discrimination? Loyola Los Angeles Law Rev 2012;45:849 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cochran SD, Mays VM. Risk of breast cancer mortality among women cohabiting with same sex partners: findings from the National Health Interview Survey, 1997-2003. J Womens Health 2012;21:528–33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.