Abstract

Objectives

Delivery of inhaled medications to infants is usually very demanding and is often associated with crying and mask rejection. It has been suggested that aerosol administration during sleep may be an attractive alternative. Previous studies in sleeping children were disappointing as most of the children awoke and rejected the treatment. The SootherMask (SM) is a new, gentle and innovative approach for delivering inhaled medication to infants and toddlers. The present pilot study describes the feasibility of administering inhaled medications during sleep using the SM.

Design

Prospective observational study.

Setting

Out patients.

Participants

13 sleeping infants with recurrent wheezing who regularly used pacifiers and were <12 months old.

Intervention

Participants inhaled technetium99mDTPA-labelled normal saline aerosol delivered via a Respimat Soft Mist Inhaler (SMI) (Boehringer-Ingelheim, Germany) and SM + InspiraChamber (IC; InspiRx Inc, New Jersey, USA).

Outcomes

The two major outcomes were the acceptability of the treatment and the lung deposition (per cent of emitted dose).

Results

All infants who fulfilled the inclusion criteria successfully received the SM treatment during sleep without difficulty. Mean lung deposition (±SD) averaged 1.6±0.5% in the right lung.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated that the combination of Respimat, IC and SM was able to administer aerosol therapy to all the sleeping infants who were regular pacifier users with good lung deposition. Administration of aerosols during sleep is advantageous since all the sleeping children accepted the mask and ensuing aerosol therapy under these conditions, in contrast to previous studies in which there was frequent mask rejection using currently available devices.

Clinical Trial Registry

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Delivery of inhaled medications to infants is often associated with crying and mask rejection. Treatment during sleep may be an attractive alternative, yet previous studies failed to confirm this approach as most of the infants awoke during treatment.

The present study describes a novel approach to overcoming these problems during sleep.

Treatment during sleep by means of a unique mask, which includes the infants’ own pacifier, was accepted by all infants with no awakening and improved lung deposition.

Only infants who regularly used pacifiers were enrolled; thus, these results may not be generally applicable.

Because the study involved scintigraphy, no control infants using conventional masks could be included.

Introduction

Delivery of inhaled medications to awake infants and toddlers is often very demanding and is frequently associated with considerable crying and rejection of the mask. It was suggested that aerosol therapy during sleep may be an attractive alternative. An in vitro study suggested that since sleep is associated with more regular breathing patterns, and lung targeting of aerosol is greater during sleep, this may translate into improved in vivo results.1

A previous real-life study using a pressurised metered dose inhaler (pMDI) with a valved aerosol holding chamber (VHC) in young children2 provided disappointing results; 69% of the children awoke during aerosol administration, and there was poor compliance and negligible benefit. No similar study followed this failure and a recent Canadian report discourages parents from this practice.3

The SootherMask (SM) is a novel approach for delivering inhaled medication to infants.4 The SM utilises the infant’s own pacifier (or the teat of an infant formula bottle), whose nipple is inserted through a slot in the anterior wall of the mask. The infant, sucking on the mask, keeps the mask sealed to its facial contours, by means of subatmospheric pressure, with little additional applied force and can nasally inhale the medication generated by a nebuliser or from an MDI+VHC attached to the SM. By virtue of its design, the SM can initially be applied to the face without the VHC or nebuliser attached. The infant can retain the SM for prolonged periods of time and subsequent gentle mating of the VHC with MDI or nebuliser rarely upsets the infant. Pilot observations suggested a high degree of acceptance of the SM in sleeping infants who appear to regard it as being no different from their pacifier alone.

The present study describes the feasibility of administering inhaled medications during sleep using the SM. Infants, shortly after falling asleep, were given 99 mTc in normal saline as placebo aerosolised medication using the SM attached to a VHC and both right lung and total lung deposition were evaluated scintigraphically. Acceptability of the treatment and fractional lung deposition served as the primary outcomes.

Methods

This was part of a larger study that explored the relationship between use of pacifiers and reduction in sudden infant death syndrome mortality (NCT01120938). The infants received the Respimat-generated radiolabelled aerosol through an SM attached to a VHC (InspiraChamber, IC) (InspiRx Inc, New Jersey, USA) and their lung aerosol deposition was measured scintigraphically.

Inclusion criteria: Infants (age 0–12 months) who were prescribed intermittent or regular inhaled therapy by a paediatric pulmonologist because of recurrent (>3× within the past 2 months) episodes of wheezing that responded to bronchodilator treatments, and who were regular users of pacifiers (at least 2 h/day of pacifier use per parents’ report). Patients had to be asymptomatic for at least 2 weeks prior to the study. Demographic details are shown in table 1.

Table 1.

Individual deposition values (per cent of emitted dose)

| Patient # | Age (months) | Gender | Right lung | Both lungs | Stomach | Upper airway |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 6.4 | M | 0.99 | 4.16 | 0.09 | 7.8 |

| 2 | 3.9 | F | 1.44 | 2.97 | 0.72 | 16.9 |

| 3 | 6.4 | M | 0.83 | 2.38 | 3.29 | 25.84 |

| 4 | 7.1 | F | 1.94 | 5.26 | 2.11 | 15.59 |

| 5 | 5.4 | F | 1.47 | 4.51 | 1.26 | 9.76 |

| 6 | 11.7 | M | 2.37 | 6.33 | 0.8 | 32.81 |

| 7 | 5.0 | F | 2.29 | 4.88 | 1.58 | 16.5 |

| 8 | 10.8 | F | 1.4 | 4.02 | 1.13 | 8.37 |

| 9 | 5.4 | M | 1.19 | 2.41 | 2.52 | 15.01 |

| 10 | 5.4 | M | 2.23 | 4.75 | 0.72 | 18.95 |

| Mean | 9.28 | 1.61 | 4.17 | 1.42 | 16.75 | |

| SD | 0.68 | 0.56 | 1.27 | 0.97 | 7.81 |

Exclusion criteria: Patients whose parents reported a history or symptoms of airway abnormalities (eg, previous airway surgery, tracheotomy, obstructive sleep apnoea, snoring, anatomical anomalies of mouth palate nose, pharynx and trachea) as well as those with chronic cardiopulmonary disease such as bronchopulmonary dysplasia, congenital heart disease, immune deficiency or cystic fibrosis.

Procedures

99 mTc labelled aerosol generated by the Respimat Soft Mist Inhaler (SMI) was administered to the infants via the IC+SM. The Respimat is powered by compressed air produced by means of a spring-driven piston within a small cylinder and generates a slowly moving aerosol bolus into the IC. The medication solution reservoir is a multidose plastic cartridge. We found the Respimat SMI to be preferable to pMDI because it is possible to readily radiolabel the medication solution in the cartridge. As pMDI and SMI, would, in infants, be used with a VHC, the Respimat served as an ideal clinical surrogate. For each trial, the SMI cartridge was filled with 3 mL of 99mTc-labelled normal saline. Addition of 99 mTc has no physical effect on aerosol characteristics.5

After priming the Respimat by discharging the inhaler five times to a hooded exhaust system, the emitted dose in terms of radioactive counts was measured by placing bacterial filters over the mouthpiece of the SMI and firing five puffs directly into the filter. The filters were immediately placed in a well counter (Capintec, Ramsey New Jersey, USA) and were evaluated each morning (×4) for reproducibility.

Infants arrived at the nuclear medicine department in the morning and were fed. The caregiver inserted the infants’ pacifier into the SM which was then offered and accepted. They were put down to sleep sucking on the pacifier nipple in the SM. Treatment started within 10 min after the infant fell asleep. The time from arrival to sleep in this strange environment ranged between 0.5 and 1.5 h. The Respimat was inserted into the back of the IC, and the ‘mouthpiece’ of the IC was gently ‘docked’ into the orifice of the SM sealed to the infant's face by its suction on the pacifier nipple. Two successive ‘puffs’ from the Respimat, each followed by 1 min of tidal breathing, were then fired into the IC and the mask-VHC-inhaler combination was kept on the infant’s face, by the caregiver, for 1 min (see figure 1 and online supplementary video 1). This ensured complete evacuation of the aerosol from the VHC.6 The SM+VHC were then removed.

Figure 1.

Photograph illustrating the method of aerosol administration to a sleeping infant showing the Respimat inhaler, InspiraChamber and SootherMask.

The infant was placed supine under a double (anterior and posterior) plate scanner (Symbia, Siemens GMBH, Munich, Germany), which enabled image acquisition without moving the infant or the cameras. Scintigraphic scans of 60 s duration were obtained and γ camera counts (corrected for decay and tissue attenuation) of the anterior and the posterior chest were measured as previously reported.7 Similarly, counts were measured for the VHC and mask to account for all the emitted doses. The tissue attenuation factor was determined based on our own experience with similar age infants.8 In brief, a hollow acrylic disc, filled with a solution of a known amount of 99mTc (37–74 MBq), served as the flood source. The square root of the ratio of transmission scan counts obtained without the infant (No) to the geometric mean of the counts with the infant (Nt) provided the attenuation correction factor (√ No/Nt).

The following regions of interest were evaluated: (1) upper airway, (2) stomach and (3) lungs. Aerosol deposition in each of these regions was expressed as the per cent of the total radioactivity previously emitted (2 puffs) from the Respimat.

Treatments were administered in a special room within the nuclear medicine department, used only for this purpose. Only the patient's parent and physician were allowed in the room. Radioactivity protection monitoring was carried out regularly and following each study, to ensure that no excess radioactivity was present in the room following the treatments. To avoid contamination of the infant’s chest and the environment during treatment, which would interfere with lung scintigraphy, the infant’s chest and the VHC were enclosed in a special disposable large volume nylon wrap which was removed immediately prior to imaging.

The radiation dose of 99 mTc aerosol used in this study was calculated according to the Medical Internal Radiation Dose Committee.9 The dose of 99 mTc to be given to each patient, which was determined before the inhalation procedure, was found to be 15μCi/kg.10 As inhalation exposure is 0.05 RAD/mCi, or 0.00075 RAD/kg, the maximum exposure for a 20 kg child was 0.015 RAD. This is equivalent to the radiation received during normal cosmic-ray exposure of 3 weeks or a 12 h flight and is much lower than the dose used in diagnostic imaging procedures. 99 mTc is a pure γ emitter and has a 6 h physical half-life.9

The deposition method suggested here has been in clinical use worldwide for several decades and has also been used in a number of previous paediatric studies.7 11 It has regularly received ethics committee approval in the past and approval was obtained for this study from the local hospital research ethics committee (#0007-09-ZIV) and the Ministry of Health in Israel (#920090101). Parents provided written informed consent.

Results

Thirteen infants were enrolled. Ten infants completed the study. Reasons for non-completion were: one infant did not fall asleep during the observation period; one infant awoke after completing aerosol administration and, due to excessive movement, image acquisition could not be undertaken, although aerosol administration had apparently been achieved; the third infant was subsequently found to be sick with a respiratory illness. She showed abnormally high deposition in only one lung and was therefore excluded. All the infants accepted the treatment without mask rejection and no leaks were observed, reflecting a good mask to face seal. All infants were asleep flat and supine during their scintigraphic image acquisition.

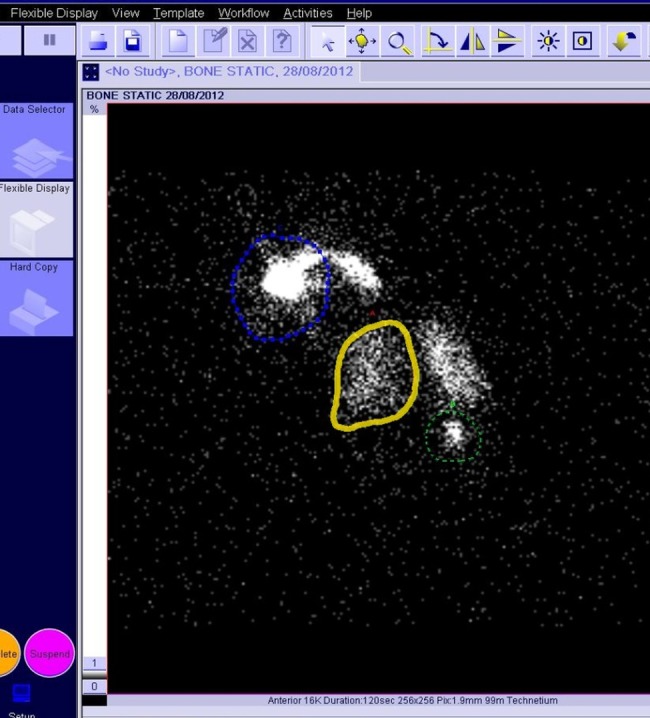

A typical scintigram is shown in figure 2. Lung deposition results for the 10 patients are shown in table 1.

Figure 2.

A typical scintigram, the green dashed circle denotes the stomach, the blue dotes denote upper airways and solid yellow denotes the right lung.

Right lung deposition in all 10 infants ranged between 0.83% and 2.37% of the total delivered dose with a mean of 1.61 + 0.56%. The mean deposition in both lungs (which includes oesophageal and carinal deposition) was 4.17%. The amount of drug deposited in the upper airway averaged 16.7% and in the stomach, 1.4%. There was no correlation between deposition and age of the infants.

Discussion

The present study demonstrates that aerosol administration to infants while asleep is a successful way to achieve potentially ‘therapeutic’ lung deposition when treatment is accomplished by means of a VHC attached to a calming and relatively non-intrusive mask such as the SM. All the infants readily accepted the treatment with little difficulty and did not awaken, cry or demonstrate fear of the mask or the subsequent aerosol therapy.

Previous studies have stressed the difficulty of delivering inhaled medications to infants and it has been suggested that sleep may provide a non-threatening opportunity for aerosol administration to them. Furthermore, compared with the awake state, sleep is associated with slower and more regular breathing and a lower inspiratory flow velocity,1 factors that have been shown to improve aerosol delivery to the lungs. Administration of inhaled medication to infants and toddlers during sleep may thus be a good alternative, particularly if they are uncooperative while awake. Murakami12 demonstrated, in seven sedated sleepy infants, that scintigraphic deposition of nebulised aerosol appeared significantly better than when they were wide awake. The mean deposition during sleep appeared as good as that in cooperative older (3–14 years) awake children.

In an aerosol ‘therapy’ study, Janssens et al1 recorded the breathing patterns of awake and sleeping babies (age 11+5.1 months), then applied the results by means of a breathing simulator. They captured the delivered aerosol (generated by MDI and delivered into a VHC) on filters located at the tracheal port of an infant airway model, the Sophia Anatomical Infant Nose-Throat model. They showed that treatment during ‘sleep’ greatly improved VHC aerosol delivery and almost doubled the lung dose compared with the ‘awake’ state: 11.3+3.9 compared with 6.5+3.2 μg of a 200 μg total delivered dose (5.5% vs 3.2%).

These promising ‘in vitro’ results were somewhat contradicted during attempts to translate them to real life conditions. Noble et al13 showed that although mask VHC aerosol administration during sleep was successful in most of the infants and toddlers that he studied, a subgroup of 17% of the patients awakened during the procedure. In a recent study that assessed the effects of sleep on aerosol delivery by VHC, it was found that 70% of infants awoke during application of the mask and 75% of those became distressed and uncooperative.

Not surprisingly, the delivered dose in this study was only about half of that in awake, cooperative infants.2 Based on these disappointing studies, a recent Canadian guideline discourages parents from attempting to deliver aerosols to their infants during sleep.3

The SM is a new face mask concept that integrates the infant's own pacifier into the treatment process. The mask has evidence-based facial contours and an extremely small dead space (18.2 mL) resulting from three-dimensional computerised face analysis technology developed with the assistance of the computer science department at Technion University.4 When infants suck on the mask-integrated pacifier, the rim of the mask becomes gently sealed to their face, mainly by suction on the pacifier and with minimal, if any, additional applied force.

We postulate that the very gentle touch of the contoured mask rim is thus not considered as intrusive and frightening as currently available masks that require application of considerable force in order to achieve a good seal14 and also fail to provide the calming effect of the infant's familiar pacifier. We have previously shown adequate lung deposition when nebulised drug was administered to awake infants through the SM.15 Nebulisation may require up to 15 min or more, which may, with current masks, be too long for the infant to tolerate. Treatment by VHC+MDI is much faster and less expensive per dose than nebulisation and the overall duration of therapy (taking into account preparation and cleaning) is considerably shorter (<5 vs >20 min).

It has been recently shown that no more than 2–3 breaths are necessary following each puff to empty the VHC in young children,6 and thus actual aerosol administration time, after application of the SM, can be as short as 10–15 s per puff. The current study is the first to employ the SM in combination with a VHC. Lung deposition in the present study was comparable with previous reports in infants (7, 8, 11, 12 and 15) and is likely to exert comparable clinical efficacy.

Respiratory symptoms such as cough and breathlessness in infancy are common during sleep.16 The present study not only supports the use of chronic anti-inflammatory treatments (eg, inhaled corticosteroids) during sleep but also suggests that the use of acute treatments such as inhaled bronchodilators at the time of an episode of nocturnal breathlessness and coughing may be rapidly effective, possibly without awaking the child. Parents can be assured that by using this technique the infants will most likely accept and receive the necessary treatment. Thus, the use of the SM is more likely than in the past to allow aerosol therapy to be administered to infants during sleep without awaking them.

Furthermore, given the high success rate with the SM approach, paediatricians may now more confidently prescribe VHC+SM to achieve more rapid and acceptable aerosol therapeutics, instead of providing more expensive compressor+nebuliser systems and solution vials that involve about 20 min of administration time and the need to clean the nebuliser after the treatment is complete. Use of nebulisers requires that a mask be applied to the face for a much longer period of time, which is more likely to arouse the infant, further adding to its distress or the need to resort to the ‘blow-by’ technique that provides a relatively small and unpredictable dose of aerosol medication to the child.

The lack of control participants using currently available conventional masks is acknowledged as a limitation of the present study and a control group was originally incorporated. However, we felt that it would be unethical and unjustified to expose an additional control group of infants to scintigraphy, particularly since several historical scintigraphic studies are available. Another limitation may be our enrolment of only infants who regularly use pacifiers and a future study of non-pacifier users is certainly warranted. Similarly, the possibility that sleep may be disturbed when infants are sick needs to be also considered in the future.

This pilot study with the SM is clinically important as it demonstrates a unique, innovative and apparently effective approach to providing infants and toddlers with aerosol therapy during sleep. It has the potential to encourage paediatricians to use this technique in future clinical studies including more patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Joanna MacLean for her valuable suggestions.

Footnotes

Contributors: IA conceptualised and designed the study, coordinated and supervised data collection, drafted the initial manuscript and reviewed and approved the final manuscript as submitted. MTN was involved in the study design, and reviewed and approved the final manuscript as submitted. AL reviewed and approved the final manuscript as submitted. AH was involved in the study design; he designed the data collection instruments and coordinated and supervised data collection. He reviewed and approved the final manuscript as submitted. HO carried out the nuclear medicine studies and initial analyses and reviewed and approved the final manuscript as submitted. MG was involved in the study design; he designed the nuclear data collection, reviewed and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: MTN is the consulting Chief Medical Officer of InspiRx Inc, developer of the SootherMask.IA and MTN have patent rights for devices for delivering aerosols to infants including those in the current study

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Ziv Medical Center IRB and Israeli Ministry of Health.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Janssens HM, van der Wiel EC, Verbraak AF, et al. Aerosol therapy and the fighting toddler: is administration during sleep an alternative? J Aerosol Med 2003;16:395–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Esposito-Festen J, Ijsselstijn H, Hop W, et al. Aerosol therapy by pressured metered-dose inhaler-spacer in sleeping young children: to do or not to do? Chest 2006;130:487–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith C, Goldman RD. Nebulizers versus pressurized metered-dose inhalers in preschool children with wheezing. Can Fam Physician 2012;58:528–30 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amirav I, Luder AS, Halamish A, et al. Design of aerosol face masks for children using computerized 3D face analysis. J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv 2013. [serial online 28 Sep 2013]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Newman SP. Scintigraphic assessment of therapeutic aerosols. Crit Rev Ther Drug Carrier Syst 1993;10:65–109 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schultz A, Le Souëf TJ, Venter A, et al. Aerosol inhalation from spacers and valved holding chambers requires few tidal breaths for children. Pediatrics 2010;126:e1493–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Amirav I, Balanov I, Gorenberg M, et al. Nebulizer hood compared to mask in wheezy infants: aerosol therapy without tears! Arch Dis Child 2003;88:719–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Amirav I, Balanov I, Gorenberg M, et al. Beta agonist aerosol distribution in RSV bronchiolitis in infants. J Nucl Med 2002;43:487–91 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Atkins HL, Weber DA, Susskind H, et al. MIRD dose estimate report no. 16: radiation absorbed dose from technetium-99m-diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid aerosol. J Nucl Med 1992;33:1717–19 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eggli DF. Pediatric radiopharmaceutical dosages. In: Taylor A, Datz FL, eds. Clinical practice of nuclear medicine. Churchill Livingstone, 1991:450 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tal A, Golan H, Grauer N, et al. Deposition pattern of radiolabeled salbutamol inhaled from a metered-dose inhaler by means of a spacer with mask in young children with airway obstruction. J Pediatr 1996;128:479–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murakami G, Igarashi T, Adachi Y, et al. Measurement of bronchial hyperreactivity in infants and preschool children using a new method. Ann Allergy 1990;64:383–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Noble V, Ruggins NR, Everard ML, et al. Inhaled budesonide for chronic wheezing under 18 months of age. Arch Dis Child 1992;67:285–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shah SA, Berlinski AB, Rubin BK. Force-dependent static dead space of face masks used with holding chambers. Respir Care 2006;51:140–4 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Amirav I, Luder A, Chleechel A, et al. Lung aerosol deposition in suckling infants . Arch Dis Child 2012;97:497–501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clarisse B, Demattei C, Nikasinovic L, et al. Bronchial obstructive phenotypes in the first year of life among Paris birth cohort infants. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2009;20:126–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.