Abstract

Objective

Describe the roles and respective responsibilities of pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) health care professionals (HCPs) in end-of-life care decisions faced by PICU parents.

Design

Retrospective qualitative study

Setting

University based tertiary care children’s hospital

Participants

Eighteen parents of children who died in the PICU and 48 PICU HCPs (physicians, nurses, social workers, child-life specialists, chaplains, and case managers).

Interventions

In depth, semi-structured focus groups and one-on-one interviews designed to explore experiences in end-of-life care decision making.

Measurements and Main Results

We identified end-of-life care decisions that parents face based on descriptions by parents and HCPs. Participants described medical and non-medical decisions addressed toward the end of a child’s life. From the descriptions, we identified seven roles HCPs play in end-of-life care decisions. The family supporter addresses emotional, spiritual, environmental, relational and informational family needs in a nondirective way. The family advocate helps families articulate their views and needs to HCPs. The information giver provides parents with medical information, identifies decisions or describes available options, and clarifies parents’ understanding. The general care coordinator helps facilitate interactions among HCPs in the PICU, among HCPs from different subspecialty teams, and between HCPs and parents. The decision maker makes or directly influences the defined plan of action. The end-of-life care coordinator organizes and executes functions occurring directly before, during and after dying/death. The point person develops a unique trusting relationship with parents.

Conclusions

Our results describe a framework for HCPs’ roles in parental end-of-life care decision making in the PICU that includes directive, value-neutral and organizational roles. More research is needed to validate these roles. Actively ensuring attention to these roles during the decision-making process could improve parents’ experiences at the end of a child’s life.

Keywords: roles, qualitative research, pediatric intensive care unit, end-of-life care, communication, decision making

INTRODUCTION

More research is needed on end-of-life care decision making in the intensive care unit (ICU).[1–3] Parents of children facing the possibility of death in the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) encounter challenging medical decisions such as: pursuing high-risk therapies associated with uncertain outcomes; withdrawing or limiting life-sustaining treatments; and organ donation. Parents also face nonmedical choices such as deciding: whether to remain with their child during procedures; what to tell their child and/or a sibling(s); and whether asking difficult questions may alienate clinicians.

Decision theory suggests that most decisions represent one point in a process reflecting multiple influences that range from unconscious, intuitive components to logical, analytical considerations.[4, 5] Reported influences that shape parental decision making and, if the child dies, impact parents’ end-of-life and bereavement experiences include: physician recommendations, communication with health care professionals (HCPs), faith, time, predictions of survival and quality of life, intuition, trust of HCPs, and feeling a sense of caring from HCPs.[6–8] These data show the important influence that HCPs have in parental decision making and the potential for HCPs to impact how families interpret and reflect on their experience. Despite the importance of HCPs, we know little about the roles and responsibilities PICU HCPs play during end-of-life care decision-making.

Role theory explores characteristic behaviors of persons within a context or process.[9] A role is a set of behaviors associated with a particular position.[10] Roles define the part(s) individuals play and responsibilities describe expectations of individuals taking on a role.[11, 12] Defining roles and responsibilities establishes a framework for relationships within groups that work together. HCPs regularly assume roles and responsibilities. For example, in the operating room persons from different disciplines (surgery, anesthesiology, nursing) assume specific roles and carry out their associated responsibilities. Defining roles can be used in healthcare settings to inform improvements to healthcare delivery.[10, 13]

The overall goals of the project are to describe issues important in PICU end-of-life care decision making and identify possible methods for improving the decision-making process for parents. Here we use experiential data from parents whose children died in the PICU and with hospital-based HCPs who care for PICU patients to define end-of-life care decisions faced by PICU parents and to describe the associated roles and respective responsibilities of PICU HCPs. From our results we propose a roles framework for HCPs helping parents who face end-of-life care decisions in the PICU.

METHODS

Setting, Participants, and Study Design

Between March 2007 and June 2009, we conducted one-on-one interviews with parents of children who died in a university-based, tertiary-care children’s hospital PICU and semi-structured focus groups or interviews with HCPs who care for PICU patients. The hospital’s institutional review board approved the study.

We identified participants using purposeful sampling.[14] We describe the details of participant recruitment elsewhere.[15] Briefly, in a pilot phase, the hospital bereavement coordinator identified parents based on her perception of the parent’s readiness to participate. Subsequently we identified and invited participation from all parents of children who died in the PICU between March 2007 and June 2009, unless parents: 1) were less than 18 years of age; 2) were unable to communicate fluently in English; 3) had a child admitted with known or suspected non-accidental trauma; 4) had a child who died less than 6 months prior (out of respect for their acute grief); 5) were parents of a child ≥ 8 years old; or 6) were without available contact information. We focused on parents of younger children, as those patients rarely have the capacity to participate in end-of-life care decisions, attempting to establish a degree of homogeneity regarding patient noninvolvement. We informed eligible parents about the study by mail. If parents did not respond, we followed our initial letter with a second letter or with three attempts to contact parents by phone. For nonresponders or those we could not contact by phone, we sent a final letter requesting participation. We continued parent data collection until reaching data “saturation.”[14] We determined saturation by study team consensus that parents were not describing new concepts. We obtained patient information via chart review.

We solicited participation from PICU HCPs through the PICU website, email, staff meetings, and posters. As with the parents, the first HCP focus group, involving eight PICU bedside nurses, was a pilot. Subsequently, we conducted separate focus groups with PICU attending physicians, PICU fellows, PICU pediatric nurse practitioners, PICU bedside nurses, chaplains, and social workers. One child-life specialist participated in the social worker focus group. One case manager participated in the chaplain focus group. Given the limited number of providers in each HCP groups, we decided a priori to conduct one focus group for each type of HCP, except besides nurses which we decided to oversample because of the large number of PICU bedside nurses. Because scheduling conflicts made it difficult to convene bedside nurse focus groups, we conducted two one-on-one interviews with bedside nurses prior to successfully convening three focus groups.

A physician or a social worker conducted the parent interviews. Neither interviewer provided clinical care to the children whose parents were interviewed. A social worker conducted all clinician focus groups and interviews. Interviewers/moderators used an interview guide intended to encourage discussion about issues important in PICU end-of-life care decision making and considerations about improving the decision-making process for parents. We interviewed parents in their home or at the hospital. We conducted HCP interviews and focus groups in the hospital. Participants completed a short questionnaire about basic demographics.

We developed our initial interview guides using information from published studies and discussions with experts in pediatric palliative care, sociology, parental bereavement, and parents of two children who died in the PICU. We asked parents to identify and discuss important decisions they faced as their child was dying in the PICU. We asked clinicians to identify all important end-of-life care decisions and subsequently focus on decisions to limit or withdraw life-sustaining therapies. We included questions on: the processes used in making decisions; the roles various individuals play in decision making; clinician-family communication; the influence of religion, faith or spirituality on decisions; and suggestions for improvements. We modified the interview guides based on ongoing data analysis, an iterative approach to data collection typical of qualitative research.[16] Our modifications included adjustments to concentrate on decision making rather than other aspects of patients’ and families’ PICU experiences.

We include data from our pilot study (eight parent interviews and one focus group with six bedside PICU nurses) because: we made only minor modifications to the study design following the pilot (in addition to the interview guide changes noted above, we added an item on our questionnaire about Hispanic/Latino ethnicity); the pilot data contain rich information which added to our understanding of PICU end-of-life care decision making; we found no substantive content differences in data between those in the pilot and later phases; and we make no assumptions that our results are generalizable beyond the studied population.

Data Analysis

Audio recordings were transcribed verbatim and personal identifiers removed. A multidisciplinary group (a PICU attending, a sociologist, and a medical student) analyzed the data.. In our initial review, we conducted open coding (labeling of data based on ideas, concepts, patterns and properties identified) of the entire dataset.[14] From this coding, the category, “roles” emerged. Also in our initial review, we identified end-of-life care decisions that PICU parents face based on parents’ accounts and reports by HCPs, and categorized the decisions described. The descriptions of end-of-life care decisions faced by parents defined the context of our roles analysis.

We identified a subset of the data that included comments related to roles, broadly defined as actions, activities and behaviors of HCPs, parents, family members and others who provided support to parents regarding end-of-life care decisions. We included individual’s discussions of his/her role in a given situation (often in response to our question asking people to comment on their role in end-of-life care decision making); descriptions of specific actions, activities and behaviors that participants reported as actually or typically occurring; and comments about absent actions, activities and behaviors that people thought ought to occur or wished would have occurred. Through iterative transcript review and discussions we identified seven distinct, though overlapping roles reflecting actions, activities and behaviors of HCPs supporting parents’ end-of-life care decision making. We then recoded the data to identify discussions pertaining to each of the seven roles. Finally, we refined our description of each role and characterized the responsibilities associated with each role using the recoded dataset.

We used ATLAS.ti Version 6.0.15 (Atlas.ti scientific software development GMBH, Berlin, Germany) for coding. We applied a Fisher’s Exact test and the Mann-Whitney U test to compare categorical and continuous variables respectively. We used SPSS version 12.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL) for quantitative analysis.

RESULTS

Participants

As reported previously,[15] for the pilot parent interviews we mailed letters to 30 parents of 15 patients who died in the PICU from 2003 – 2006. We conducted eight individual interviews with parents of six patients. For subsequent parent interviews, we reviewed PICU deaths between February 2006 and January 2009. Forty-eight patients met our inclusion/exclusion criteria. Letters to 96 parents of these patients yielded 11 interviews with the parents of eight patients. Technical difficulties with the recording prohibited analysis of one interview. We report results from the analysis of 18 parent interviews. We found no difference in sex (29% vs. 43% female, p=0.37), age (2.2 vs. 2.1 years, p=0.81), length of PICU stay (0.02 vs. 0.04 years, p=0.21), or length of hospital stay (0.03 vs. 0.05 years, p=0.18) between patients of parents interviewed vs. those not interviewed. Parents in the pilots group versus the subsequent group were slightly older (average age 32 vs. 39 years old respectively), had more time between their child’s death and the interview (2.4 vs. 1.4 years respectively), and were all white. We conducted nine focus groups and two nurse interviews involving 48 clinicians. Tables 1, 2 and 3 give demographic information about parent participants, the patients, and HCP participants, respectively. Based on parent reports, four children had previous ICU admissions, all the children received conventional mechanical ventilation during their PICU admission, and two children required extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) while in the PICU.

Table 1.

Parent Demographics (n = 18)

| Characteristic | n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | Female | 11 (61) |

| Male | 7 (39) | |

|

| ||

| Age | Mean (sd) | 35 (6.6) |

| Median | 34 | |

| Range | 19 – 47 | |

|

| ||

| Marital Status | Married | 16 (89) |

| Never Married | 1 (6) | |

| Partnered, not married | 1 (6) | |

|

| ||

| Education | College 1 – 3 years | 5 (28) |

| College Graduate | 4 (22) | |

| Graduate School | 8 (44) | |

| Missing | 1 (6) | |

|

| ||

| Religion | Protestant | 4 (22) |

| Catholic | 8 (44) | |

| Jewish | 2 (11) | |

| Spirituala | 1 (6) | |

| Other | 3 (17) | |

|

| ||

| Race | Asian | 1 (6) |

| Black | 1 (6) | |

| White | 16 (89) | |

|

| ||

| Ethnicity | Hispanic/Latino | 1 (6) |

| Not Hispanic/Latino | 10 (56) | |

| Missing datab | 7 (39) | |

|

| ||

| Incomec | ≤ 49,999 | 4 (22) |

| 50,000 – 74,999 | 1 (6) | |

| 75,000 – 99,999 | 4 (22) | |

| ≥ 100,000 | 9 (50) | |

|

| ||

| Years after child’s death | Mean (sd) | 1.9 (0.83) |

| Median | 1.8 | |

| Range | 0.62 – 3 | |

Abbreviations: sd, standard deviation

Not affiliated with an organized group

This item not included on 7 post-interview questionnaires.

Total household income

Table 2.

Patient Demographics (n = 13)

| Characteristic | n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | Female | 5 (39) |

| Male | 8 (62) | |

|

| ||

| Age at death (years) | Mean (sd) | 1.9 (2.2) |

| Median | 0.53 | |

| Range | 0.06 – 6.5 | |

|

| ||

| Existing chronic condition(s) | Yes | 7 (54) |

| Noa | 6 (46) | |

|

| ||

| Limitation of medical therapies prior to PICU admission | Yes | 0 (0) |

| No | 13 (100) | |

|

| ||

| Limitations of medical therapies prior to deathb | Yes | 12 (92) |

| No | 1 (8) | |

|

| ||

| PICU length of stay (days) | Mean (sd) | 8.7 (11) |

| Median | 3 | |

| Range | 0 – 38 | |

|

| ||

| Cause of death | Neoplasm | 7 (54) |

| Heart diseasec | 3 (23) | |

| Bowel perforation | 1 (8) | |

| Sepsis | 1 (8) | |

| Trauma | 1 (8) | |

Abbreviations: PICU, pediatric intensive care unit; sd, standard deviation

Includes three patients with new cancer diagnoses at the time of hospital admission, a newborn with congenital heart disease, a patient admitted following trauma, and a patient admitted following cardiopulmonary arrest

Includes patients for whom life-sustaining therapies were withdrawn and/or there was a “do not resuscitate” order in the chart.

Includes two patients who underwent surgery for congenital heart disease and one patient with an arrhythmia.

Table 3.

Health Care Professional Demographics (n = 48)

| Characteristic | n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Position | Attending Physician | 7 (15) |

| Chaplain | 4 (8) | |

| Child-Life specialist | 1 (2) | |

| Fellow Physician | 6 (13) | |

| Nurse (bedside) | 20 (42) | |

| Nurse (PNP) | 3 (6) | |

| Social Worker | 6 (13) | |

| Case Manager | 1 (2) | |

|

| ||

| Years in current field | Mean (sd) | 8.8 (8.6) |

| Median | 5 | |

| Range | 0.33 – 33 | |

| Missing | 6 | |

|

| ||

| Sex | Female | 35 (73) |

| Male | 8 (17) | |

| Missing | 5 (10) | |

|

| ||

| Age | Mean (sd) | 37 (10.4) |

| Median | 35 | |

| Range | 22 – 68 | |

| Missing | 5 | |

|

| ||

| Marital Status | Married | 17 (35) |

| Widowed | 1 (2) | |

| Divorced | 1 (2) | |

| Never Married | 21 (44) | |

| Partnered | 2 (4) | |

| Missing | 6 (13) | |

|

| ||

| Religion | Protestant | 7 (15) |

| Catholic | 19 (40) | |

| Jewish | 4 (8) | |

| Spirituala | 5 (10) | |

| Otherb | 4 (8) | |

| Not religious | 4 (8) | |

| Missing | 5 (10) | |

|

| ||

| Race | Asian | 2 (4) |

| Black | 1 (2) | |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 1 (2) | |

| White | 36 (75) | |

| Otherc | 1 (2) | |

| Missing | 7 (15) | |

|

| ||

| Ethnicity | Hispanic/Latino | 1 (2) |

| Not Hispanic/Latino | 37 (77) | |

| Missingd | 10 (21) | |

Abbreviations: PNP, pediatric nurse practitioner; sd, standard deviation

Not affiliated with an organized group

Includes 2 Hindu, 1 Lutheran, and 1 Christian (all self-identified)

Self-identified as “Indian”

This item not included on 6 post-interview questionnaires

Defining the context: PICU End-of-Life Care Decisions

Descriptions of end-of-life care decisions faced by parents in the PICU included medical decisions as well as non-medical decisions prior to and during the dying/death period. (See Table 4.)

Table 4.

Decisions discussed by Health Care Professionals and Parents

| Medical Decisions | |

| Prior to dying/death period | During dying/death period |

| Giving chemotherapy | Avoiding cardiopulmonary resuscitation* |

| Doing surgery | Withdrawing life-sustaining therapies |

| Intubating the patient | Limiting administration of certain medications |

| Placing a tracheostomy tube | Withdrawing certain medications |

| Placing a gastrostomy tube | Giving pain medication |

| Starting ECMO | Providing fluids |

| Starting CRRT | Having an autopsy performed |

| Using and advancing pressors/ionotropes | Donating organs |

| Introducing chronic ventilation | |

| Doing a stem cell/solid organ transplant | |

| Agreeing to involvement of hospice or palliative care | |

|

| |

| Nonmedical Decisions | |

| Prior to dying/death period | During dying/death period |

| Accepting/trusting the healthcare team | Participate in memory making activities** |

| Asking questions of the healthcare team | Going home versus staying in the hospital |

| Agreeing to involvement of hospice or palliative care | Taking the patient outside his/her room |

| Encouraging respite for spouse | Holding patient |

| Talking to the patient about dying | Determining who can be present |

| Involving other family members or support people*** | Involving other family members or support people**** |

| Spending time with patient after death | |

| Having religious ceremonies | |

Abbreviations: ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; CRRT, continuous renal replacement therapy

No chest compressions, defibrillation and/or codes medications

Memory making activities include: hand/foot prints or molds, bereavement photography, keeping a lock of hair, bathing and/or dressing the patient

Includes involvement of siblings and religious figures in the decision making process and/or hospital experience

Includes involvement of siblings and religious figures in the end-of-life experience

Roles and Responsibilities of HCPs

We identified seven HCP roles. Table 5 describes the general responsibilities for each role with illustrative quotes. While distinct, the responsibilities associated with some roles overlap. Nothing from our data indicates that each role is, or ought to be, filled by one specific HCP or even by one type of HCP. For example, physicians and nurses provide information to parents, thus both fill components of the information giver role. Also one HCP may assume responsibilities associated with multiple roles. For example, someone could be a family supporter and an information giver. Below we characterize each role and indicate whether HCPs, parents, or both described the roles. When possible we note which HCPs commonly fill each role.

Table 5.

Role responsibilities and illustrative quotes

| Role Responsibilities | Illustrative Quotes |

|---|---|

| Family Supporter | |

| Provides nonjudgmental emotional support through conversation, listening, touch and physical presence | “We [social workers and child life specialists] are neutral and are their sounding boards in the process.” Social worker “They told us that and they supported our decision, and … they were really at our disposal I think for that day, so I’m not sure you can ask for anything more.” Parent |

| Provides spiritual support through conversation, facilitating meetings with appropriate spiritual advisors and facilitating engagement in spiritual rituals | “Spiritual issues and how God is involved and active in this situation … And so, I think the chaplain helps sort out and talk about some of those issues.” Chaplain “It was really important to us to have him baptized there and so everybody was very professional and, and giving us that time in -- you know to do that.” Parent |

| Addresses physical and environmental needs of family (e.g. food, space to sleep, quiet area) | “[My wife] was a month off giving a 40 hour labor. … she was still nursing you know and all these things were going on. So you know they’re like well ‘let’s not have someone else in the hospital’ kind of conversations.” Parent “And I remember being angry having experienced what we just experienced, but they wouldn’t take care of [my husband]. They wouldn’t give him a place to go and just fall apart, which is what he needed.” Parent |

| Fosters connectedness or relatedness between HCPs with parents/patients and between parents/patients with others | “We had a sign. We had a big billboard, … And so even the people that were doing the ECMO and the doctors and everyone who came to visit, they would write a little message to her. So that was really nice.” Parent “I mean, you know even something like being able to say to them “listen, would you like to talk to somebody else that’s been through this, another parent that we might be able to get to come down and talk to you?” Parent |

| Provides information support by helping family understand the medical information presented | “I think we should be there to translate what the doctor said, to soothe them and support them and just let them vent and explain things gently” Nurse “I guess just help reiterating the information, giving it to them in a way that’s like understandable for both of them.” Nurse |

| Parent Advocate | |

| Relays information about the parents to HCPs (e.g. parents’ perspectives, views, goals, religious/spiritual alignment, state of medical knowledge, communication preferences, education, psychosocial issues) | “And they [the parents] say ‘we get it but we, we can’t just keep talking about it. … please tell the docs … that we understand it. Tell them to stop coming in. … this is what we need to do’” Chaplain “I think that’s often our best role is before medical professionals go in and talk to them is helping educate them on history of the family or cognitive functioning of the family or family dynamics and so using us as a, you know, a resource to help have more effective conversations.” Social worker |

| Facilitates meetings between HCPs and parents in order to help families express their views and needs and to actively participate in care and decision making | “She said ‘if I was in my country she said he would not be taken care of, he would be allowed to die.’ … I said ‘we can do that here too’ and I asked [the attending] to come in and talk to her.” Nurse “We, as nurses, will quite often advocate for that, say hey, you know, we’ve got a lot of services involved, the family isn’t here during rounds, we need to set something up and sit down in one room and they can get their questions answered and everybody’s going to be on the same page.” Nurse |

| Information Giver | |

| Discusses the medical situation, describes changes and updates to clinical status and prognosticates | “I’ve seen some, some excellent examples of, of communication by a couple of our fellows with regards to updating families on where things are at and that in a sense saying things are not looking good and this is what we’ve done.” Nurse “That if the team feels like things are headed in a bad direction, I think it’s inappropriate for there to be a lag time between them feeling that or seeing that, or diagnosing that and it being communicated to the family.” Nurse |

| Presents decisions to parents; describes available options; gives recommendations | “…often the families become aware that a decision is about to happen through support staff. Through the nurses at the bedside, day in and day out and that nurse may have already started talking about you know ‘the docs might ask you about this’ or ‘the docs may ask you about that.’” Attending “Before the surgical team was doing their rounds … we asked what the options were for continuing treatment and, you know, they talked about our, our options. That if she went into arrest, you know, they could try the compressions or the, the, you know, other attempts to revive her.” Parent” |

| Clarifies parents’ understanding by repeating information or answering questions | “And as wonderful as our provider team is, I think sometimes we still fall short of being able to really explain things in an understandable manner in non-technical terms to families. I always felt my role, as the bedside nurse was to make sure when we were done that they understood everything.” PNP “So they did explain to us everything that was going on and you know and they allowed us to participate in the rounds in the morning and ask questions when they were done.” Parent |

| General care coordinator | |

| Keeps HCPs from different services and different disciplines updated | “And I think families really resent it when they don’t, when they’re the ones that tell a physician what the other team has said.” Social worker “So I find that, you know, one person’s talking to them about it and then other, the other persons aren’t included and then nobody knows what’s going on or how to talk to them. So I think hope, trying to make it more central.” Social worker |

| Coordinates the communication of information from HCPs to parents/families | “But I feel like they all go in there with a parent, but then one team says one thing, the other team says another thing. And then they kind of banter back and forth,…why they don’t meet beforehand and why aren’t they on the same page before they even enter a room with a family?” Nurse “We just kind of took everything people would say with a grain of salt because we knew everybody sees things with a different attitude. Some people see things optimistically and some see them pessimistically, but it seemed like there was all the same facts coming from all of them.” Parent |

| Coordinates interactions between HCPs and families | “Before all these various groups come to the bedside and share tidbits of information on which direction things are going I think it would be better to have a coordinated effort where it’s one individual or one group of people that is communicating the information to the family.” Nurse “We need to coordinate not just a medical team member coming back to the bedside, but social work, or a pastor, or something like that to help provide some emotional support.” Nurse |

| Involves point people when appropriate | “When somebody who’s from a, another service who doesn’t have a relationship, … walks in and gives a piece of information that is a blow to the family, and none of the staff that have … a relationship [with the family] are present or sometimes don’t even know that this piece of information was being given. …That happens too often.” Chaplain “And it has a lot to do with how much the team stops and thinks and says oh, well can I get your child life person from oncology down to say ‘hi’.” Social worker |

| Decision Maker | |

| Makes the decision or defines a plan | “You have the parents who are in the active role, who make the decision. Either they come to us with the decision or they are able to make the decision after they’re given their options. … And then there’s the passive deciders. … those people who say we’ll do whatever you recommend.” PNP “You’ve come from a team that’s been telling you when you’re going to eat and when you’re going to sleep … and then at the end of life we sort of, the, the attending physicians tend to say gosh, we don’t know any better than you do. What do you want to do? And it’s a huge role reversal.” Social worker “I still think that I removed that breathing tube. The doctor might have removed it, but I did. Physically the doctor, but emotionally I did, and it hurts.” Parent |

| Influences and/or directs the choice of primary decision maker | “you walk in that room either intending to tell them what’s happening next, intending to get their opinion about what to do next or intending to educate them so that they eventually agree with what your thought processes are. It is rare that you walk in a room with sort of fifty-fifty on the table and ask them to make a [decision] … You go in the room with a loaded deck …” Attending “And I think the parents should have a right to say no, I don’t want CRRT and I want my child to be made comfortable and I don’t want the drips you know and I think this should be a choice to do that. But I find a lot, a lot of times here we don’t give them that choice.” Nurse |

| End-of-life care coordinator | |

| Prepares family for dying period | “Child life preps, so to speak, the siblings if they are going to be involved in that and in the room during withdrawal or throughout the process and stuff.” Nurse “The PICU people came in and said, ‘okay, here’s what’s going to happen.’” You know, and they just gave us a checklist of what we’ll see and what he’ll do.” Parent |

| Coordinates supportive environmental changes | “And yes rooms might be crowded but I think they should have designated areas where, not to die areas, but, you know, if it gets serious, you know, it should be quiet. It should be corded off” Parent “And then they let us stay as long as we wanted. … They brought in food. … They, they also provided another room for my family to all go to and sit.” Parent |

| Coordinates visitors: family, friends, HCPs, religious figures | “So I think if, if that list [of family and friends] was prepared and you could have a social worker or somebody kind of call and inform these people what’s going on.” Parent “Nurses that were off that day showed up and all stood there and waited with us.” Parent |

| Coordinates end-of-life memory making activities and experiences by offering to help create mementos or allow time and physical interaction with the patient | “She was very compassionate. And you know she came in and asked me if I want to do footprints and handprints and you know and things you know I wouldn’t ever think to do. … And I said ‘would you mind if you left and we did this alone’ and she’s like ‘absolutely not, if you need anything I’m right outside’ you know, and she left.” Parent “There’s parents lots of times that want to hold their child who’s intubated. And they know that the child is dying, … So, sometimes those roles of figuring out when parents can step in and say to the medical team you know I want to do this regardless.” Chaplain |

| Addresses medical issues related to the patient: autopsy, coroner, organ donation | “They gave us the option for an autopsy. … If there was anything to be learned for anybody else’s sake that we wanted to make some meaning out of her death.” Parent “If somebody from the coroner’s office or somebody from the hospital who knows the drill, okay, could have just said, … ‘You know when this is all over, they’re going to take him. This is the law.’” Parent |

| Point Person | |

| Foster a trusting relationship with family through consistency and rapport building | “She’s one of the clergy, faith people here, and she was wonderful and would meet with me any time. … I definitely did bond with [that chaplain].” Parent “At that point [Dr. X] was kind of our go to. She had stuck with us. She was the one that was resuscitating her throughout the night. She slept there and continued to get up to help and, you know, but she kind of brought it [the decision] to us.” Parent “I think that that night I remember it was a little difficult because there was nobody on that we had any relationship with, that had been there during the week that I recall, you know.” Parent “I’d love to have had the same nurse or nurses. … Give us some constants. There’s nothing better than constants...” Parent |

Title of speaker is noted after the quote

Nurse signifies PICU bedside nurse

Abbreviations: PNP, pediatric nurse practitioner

The family supporter addresses emotional, spiritual, environmental, relational and information family needs in a nondirective way. Such support may focus on parents, patients, or the entire family, including siblings. Nurses, chaplains, and social workers identify this as one of their primary roles. Some physicians noted that they provide family support though doctors did not describe this as their primary focus. Conversation about family supporters came from parents and HCPs.

The family advocate helps families articulate their views and needs to HCPs. This role is filled by someone with knowledge of the medical situation and organizational structure of the PICU who takes a nonjudgmental approach to understanding and providing a voice for the family or a forum for families to express themselves. While behaviors associated with this role do support families, the family advocate role helps families bring their needs and perspectives to the health care team’s attention, whereas the family supporter role focuses directly on helping parents. This role seems to be filled largely by chaplains, social workers, and nurses. HCPs defined this role when describing their duties. Parents rarely described HCPs displaying the behaviors associated with the family advocate role.

The information giver provides parents with medical information about the patient, identifies decisions or describes available options, and clarifies parents’ understanding of the situation. Based on parents’ comments about their experiences receiving information, physicians and nurses generally fill this role. Discussions of this role included comments on how and where information was exchanged. Specifically, HCPs talked about giving direct, clear, simple, honest, timely and complete information. Professionals expressed the need to balance hope and realism when giving information. HCPs and parents described information exchange occurring in planned, formal family conferences; daily rounds; impromptu conversations at the bedside or other private spaces; and during resuscitations.

The general care coordinator helps facilitate interactions among PICU HCPs and among HCPs from different subspecialty teams. He/she also coordinates interactions between HCPs and parents. The coordinator role emerged largely from HCPs expressing concern about insufficient communication among HCPs and disorganized communication between HCPs and parents. Far less discussion from parents occurred on this topic. Those parents who did comment noted poor communication among members of the healthcare team about their child’s care. Participants indicated that coordinated communication between HCPs and families could occur in a conference or by identifying a specific person to relay information to families. HCPs also noted the importance of involving “point people” (see below). HCPs worried that parents often hear divergent recommendations or prognoses from HCPs, which could cause confusion and additional emotional burden for families. Many HCPs recommended that the medical team define and present a unified perspective on issues related to clinical status, prognosis and decision making prior to talking with parents. Parents did not express the need to receive a single message about the patient’s condition, prognosis and/or recommendations for care. One parent seemed to appreciate hearing different opinions from HCPs, suggesting that HCPs should not necessarily limit expressions of conflicting opinions.

While parents are the legal decision makers for children, our data reveal how HCPs also act as decision makers. Respondents describe two kinds of decision makers, primary and secondary. The primary decision maker determines or agrees to the clinical plan. Given the laws and culture in the United States, HCPs generally describe parents as filling this role for end-of-life care decisions, and parents generally acknowledge making final decisions regarding such things as “do not resuscitate” orders and withdrawal of life-sustaining therapies. However comments from HCPs reflect the perception that some parents may prefer that clinicians make difficult end-of-life care decisions. Both HCPs and parents note that placing parents in the position of primary decision maker represents a kind of role reversal because HCPs act as primary decision makers for most decisions encountered prior to end-of-life care decisions, like giving antibiotics, adjusting ventilators, or administering vasopressors. Roles are reversed with end-of-life care decisions when parents shift, sometimes acutely, into the role of primary decision maker.

Secondary decision makers influence the choices of the primary decision maker by censoring how and what information is conveyed to parents, through recommendations or directive comments, and by limiting options presented to families. For example, we would not expect parents to request ECMO unless physicians offered ECMO. Our data suggest that physicians or nurses generally play the role of secondary decision maker(s). Attending physicians in particular described their view that minimizing parents’ role in decision making may avoid unnecessary emotional burdens on parents. Social workers, chaplains and child life specialists specifically describe attempts to maintain a value-neutral position and not influence parents’ decisions. Parents did not comment directly on such decision making influence from HCPs, though some described following recommendations from trusted HCPs. Some parents did describe how their child’s clinical course rendered certain decisions moot.

The end-of-life care coordinator organizes and executes duties immediately before, during and after death. This role emerged from respondents’ descriptions of events that did occur or that they felt ought to occur. While many responsibilities for this role overlap with those of family supporter, information giver and decision maker, we felt certain tasks were sufficiently unique to the peri-mortem period that it warranted a distinct role. Responsibilities for this role include talking to the family about expectations for the dying process, engaging siblings and other children in developmentally appropriate discussions or activities; modifying the environment to meet the family’s needs; coordinating visitors; providing memory making opportunities; and addressing medical issues such as autopsy, coroner review, and organ donation. While physicians seem to assume the tasks pertaining to medical issues, chaplains, social workers, beside nurses, and child life specialists fill the remaining responsibilities associated with this role.

The point person fosters trust between the HCPs and parents. The person(s) filling this role takes on responsibilities associated with the other six roles. This role is distinct, however, because those in this role have a unique relationship with the family based on involvement with the family over time, presence during key moments in the patient’s clinical course (e.g., on admission or during an acute decompensation), and/or general rapport with the family. Multiple people may assume this role for any particular family, and responsibilities may be distributed among more than one point person for any patient. Thus, a trusted physician may serve as a point person regarding giving information, while a social worker or chaplain may be the point person for providing psychosocial support. This role emerged from discussions by both HCPs and parents.

DISCUSSION

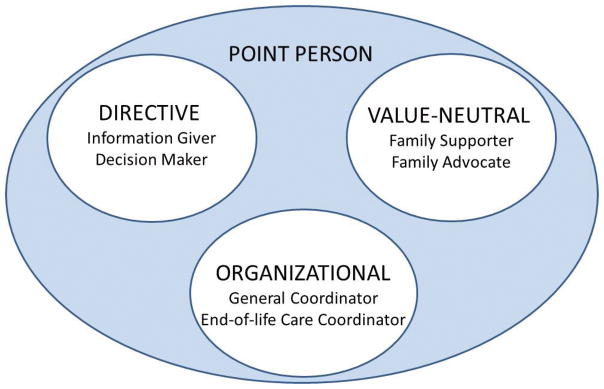

Our results suggest a framework for HCPs’ roles in PICU end-of-life care decision making that includes three categories: directive; value-neutral; and organizational. (See Figure 1.) Directive roles guide parents, intentionally or not, toward a particular course of action. Value-neutral roles support parents’ physical, cognitive, spiritual, and psychological decision making process in a nondirective way. Organizational roles address care coordination. Ideally, a point person(s), someone who has a unique trusting relationship with the parents, addresses the responsibilities of all three role categories in conjunction with other members of the team.

Figure 1.

Framework for HCP roles in PICU end-of-life care decision making

This framework parallels existing literature on ICU end-of-life care decision making. Prior research has shown that some HCPs, often nurses and physicians, assume a directive role in end-of-life decision care making either by virtue of their role as decision makers or information givers.[11, 17–20] Others have described how HCPs need to provide psychological and physical support.[17, 21] Many have noted the need for improved care coordination throughout the ICU stay and during the dying process.[20, 22] To our knowledge, this is the first comprehensive framework describing HCPs roles and their associated responsibilities in the context of PICU end-of-life care decision making.

Our proposed framework includes key features of shared decision making: providing medical information; eliciting patient/parent values and preferences; exploring the family’s preferred role in decision making; deliberation; and deciding on a care plan.[23, 24] By introducing a mechanism to actively ensure situation appropriate attention to key defined roles and responsibilities, HCPs could minimize missed opportunities for supporting shared decision making and thereby improve the decision–making process.

Additional study results merit comment. We describe the phenomenon of “role reversal,” noted by both HCPs and parents, whereby primary decision making shifts from HCPs to parents when decisions change from more “routine,” technical medical decisions, to value-laden decisions tied to end-of-life care. Recognizing that most parents/lay people do not have the expertise to direct most medical therapies, the shift that occurs with end-of-life decisions likely reflects our cultural emphasis on family autonomy and sense that parents ought to decide what is in their child’s best interest. Our description of secondary decisions makers highlights the reality that parents are not entirely responsible for end-of-life care decisions. One physician said that we give parents the “illusion” of being decision makers, suggesting there is probably not complete role reversal. HCPs recognition of the shift in decision making at the end of life could ease the transition. Perhaps one factor affecting parents’ need for time to make difficult end-of-life decisions[6] reflects their adjustment to a new, more directive decision-making role.

We also find it interesting that HCPs described the need to present parents with a unified perspective on a patient’s clinical situation and prognosis, yet parents discussed this topic much less frequently. Perhaps many parents do not feel burdened or confused by hearing different opinions. Or perhaps parents receive fewer conflicting opinions than HCPs perceive. Prospective, “real-time” research may help to clarify the extent to which parents get conflicting opinions from HCPs, parents’ reactions when presented with dissenting views, and the need, or lack thereof, to limit expressions of differing opinions from HCPs to parents.

A final remarkable observation was that families seemed to lack awareness of the family advocator role. Perhaps families need not realize that some HCPs actively attempt to facilitate the medical team’s awareness and knowledge of parents’ views and needs. We worry, however, that this observation could reflect a sense of isolation by the parents from the medical team. If parents recognized that HCPs sought to advocate for them, perhaps more parents would take advantage of such support.

We describe possible roles for HCPs in PICU end-of-life care decision making, but more work is needed. Sampling issues limit our results. We used retrospective accounts from one center. Our overall parent response rate (14 of 63, 22%) was small, though similar to that of related published studies.[25, 26] Parent participants represent a group of predominately English-speaking and mainly well-educated, white, Christian parents whose children died at less than eight years old. Responses from the parents of the same child were often similar, further limiting the representative sample of family experiences. We cannot know how similar or dissimilar views of nonparticipants might be. We have no information from parents whose children survived even when clinicians predicted and discussed death and end-of-life care decisions.

We acknowledge additional study limitations. We asked people to comment on their roles, but defining and characterizing roles was not the a priori research goal. There could there be other important roles not included in the seven we identify. While HCPs described all end-of-life care decisions they perceive that parents face, the bulk of their discussion focused on decisions related to limitation of therapies. Thus HCPs may have additional comments about their roles in relation to other decision making. Some authors (KM and JF) could have recognized comments from clinicians because of ongoing working relationships. We offset this potential bias by having two non-clinician investigators (NHB and RP) involved in the data analysis.

In light of these limitations, this study does not represent the experience of all parents and HCPs. A multi-site prospective study examining the views of parents facing life and death decisions, regardless of outcome, and the HCPs involved in such situations is needed. Next steps should assess the validity of our framework through prospective data collection at multiple sites. Such research could refine our role definitions and their associated responsibilities as needed; address differences based on PICU size, location and population/culture served; and consider how HCPs’ roles integrate with other parental influences such as interactions with extended family, friends, religious counselors and religious doctrines. Future work will also need to identify resources and barriers to filling these HCPs’ roles; consider how role integration can occur in the multidisciplinary PICU environment; address the need for role adaptation, reflecting the uniqueness of each patient’s circumstances; and identify mechanisms for renegotiating the adoption of roles by HCPs when needed during a patient’s illness experience.

CONCLUSIONS

End-of-life care decision making for parents of PICU patients encompasses a large range of challenging medical and non-medical issues. Based on seven identified roles, we propose a framework for HCPs’ roles in PICU parental end-of-life care decision making that includes three categories: directive; value-neutral; and organizational. More research is needed to validate these roles. We propose that actively ensuring attention to a validated set of defined roles and responsibilities could improve decision making for parents.

Acknowledgments

Financial support used for the study:

Dr. Michelson’s efforts and support for this study are provided by NICHD Grant number 1K23HD054441, “Developing a Pediatric Advance Care Planning Worksheet,” Principal Investigator, Dr. Kelly Michelson, Children’s Memorial Hospital, and by NICHD Grant Number K12HD047349, “Pediatric Critical Care Scientist Development Program” Principal Investigator, Dr. J Michael Dean, University of Utah.

We thank the bereaved parents and healthcare professionals who participated in the study, Mrs. Priscilla Brinkman, and Ms. Kathleen Blehart for helping to make this work possible.

Footnotes

The authors have not disclosed any potential conflict of interest.

Institution where work was performed:

Children’s Memorial Hospital, Northwestern University, Chicago, Illinois

No reprints will be ordered

References

- 1.Truog RD, Meyer EC, Burns JP. Toward interventions to improve end-of-life care in the pediatric intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(11 Suppl):S373–379. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000237043.70264.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Truog RD, Campbell ML, Curtis JR, Haas CE, Luce JM, Rubenfeld GD, Rushton CH, Kaufman DC. Recommendations for end-of-life care in the intensive care unit: a consensus statement by the American College [corrected] of Critical Care Medicine. Crit Care Med. 2008;36(3):953–963. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0B013E3181659096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Truog RD, Cist AF, Brackett SE, Burns JP, Curley MA, Danis M, DeVita MA, Rosenbaum SH, Rothenberg DM, Sprung CL, et al. Recommendations for end-of-life care in the intensive care unit: The Ethics Committee of the Society of Critical Care Medicine. Crit Care Med. 2001;29(12):2332–2348. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200112000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Croskerry P. Clinical cognition and diagnostic error: applications of a dual process model of reasoning. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2009;14 (Suppl 1):27–35. doi: 10.1007/s10459-009-9182-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eddy DM. Clinical decision making: from theory to practice. Anatomy of a decision. JAMA. 1990;263(3):441–443. doi: 10.1001/jama.263.3.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Michelson KN, Koogler T, Sullivan C, del Ortega MP, Hall E, Frader J. Parental views on withdrawing life-sustaining therapies in critically ill children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163(11):986–992. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sharman M, Meert KL, Sarnaik AP. What influences parents’ decisions to limit or withdraw life support? Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2005;6(5):513–518. doi: 10.1097/01.pcc.0000170616.28175.d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meert KL, Thurston CS, Sarnaik AP. End-of-life decision-making and satisfaction with care: parental perspectives. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2000;1(2):179–185. doi: 10.1097/00130478-200010000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Biddle B. Role theory: expectations, identities, and behaviors. New York: Academic Press, Inc; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Major DA. Utilizing role theory to help employed parents cope with children’s chronic illness. Health Educ Res. 2003;18(1):45–57. doi: 10.1093/her/18.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gordon C, Barton E, Meert KL, Eggly S, Pollacks M, Zimmerman J, Anand KJ, Carcillo J, Newth CJ, Dean JM, et al. Accounting for medical communication: parents’ perceptions of communicative roles and responsibilities in the pediatric intensive care unit. Commun Med. 2009;6(2):177–188. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ch’ng S, Padgham L. From roles to teamwork: a framework and architecture. Applied Artificial Intelligence. 1998;12:211–231. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rheiner NW. Role theory: framework for change. Nurs Manage. 1982;13(3):20–22. doi: 10.1097/00006247-198203000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Creswell JW. Qualitative inquiry and research resign: Choosing among five approaches. 2. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Michelson KN, Emanuel L, Carter A, Brinkman P, Clayman ML, Frader J. Pediatric intensive care unit family conferences: one mode of communication for discussing end-of-life care decisions. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2011;12(6):e336–343. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e3182192a98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Greenhalgh T, Taylor R. Papers that go beyond numbers (qualitative research) BMJ. 1997;315(7110):740–743. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7110.740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stern HP, Stroh SE, Fiser DH, Cromwell EL, McCarthy SG, Prince MT. Communication, decision making, and perception of nursing roles in a pediatric intensive care unit. Crit Care Nurs Q. 1991;14(3):56–68. doi: 10.1097/00002727-199111000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carnevale FA, Canoui P, Cremer R, Farrell C, Doussau A, Seguin MJ, Hubert P, Leclerc F, Lacroix J. Parental involvement in treatment decisions regarding their critically ill child: a comparative study of France and Quebec. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2007;8(4):337–342. doi: 10.1097/01.PCC.0000269399.47060.6D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Botti S, Orfali K, Iyengar S. Tragic choices: autonomy and emotional responses to medical decisions. Journal of Consumer Research. 2009;36:337–352. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baggs JG, Norton SA, Schmitt MH, Dombeck MT, Sellers CR, Quinn JR. Intensive care unit cultures and end-of-life decision making. J Crit Care. 2007;22(2):159–168. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2006.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Babcock CW, Robinson LE. A novel approach to hospital palliative care: an expanded role for counselors. J Palliat Med. 2011;14(4):491–500. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2010.0432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meert KL, Briller SH, Schim SM, Thurston C, Kabel A. Examining the needs of bereaved parents in the pediatric intensive care unit: a qualitative study. Death Stud. 2009;33(8):712–740. doi: 10.1080/07481180903070434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.White DB, Braddock CH, 3rd, Bereknyei S, Curtis JR. Toward shared decision making at the end of life in intensive care units: opportunities for improvement. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(5):461–467. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.5.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Makoul G, Clayman ML. An integrative model of shared decision making in medical encounters. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;60(3):301–312. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2005.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meert KL, Briller SH, Schim SM, Thurston CS. Exploring parents’ environmental needs at the time of a child’s death in the pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2008;9(6):623–628. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e31818d30d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meert KL, Eggly S, Pollack M, Anand KJ, Zimmerman J, Carcillo J, Newth CJ, Dean JM, Willson DF, Nicholson C. Parents’ perspectives on physician-parent communication near the time of a child’s death in the pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2008;9(1):2–7. doi: 10.1097/01.PCC.0000298644.13882.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]