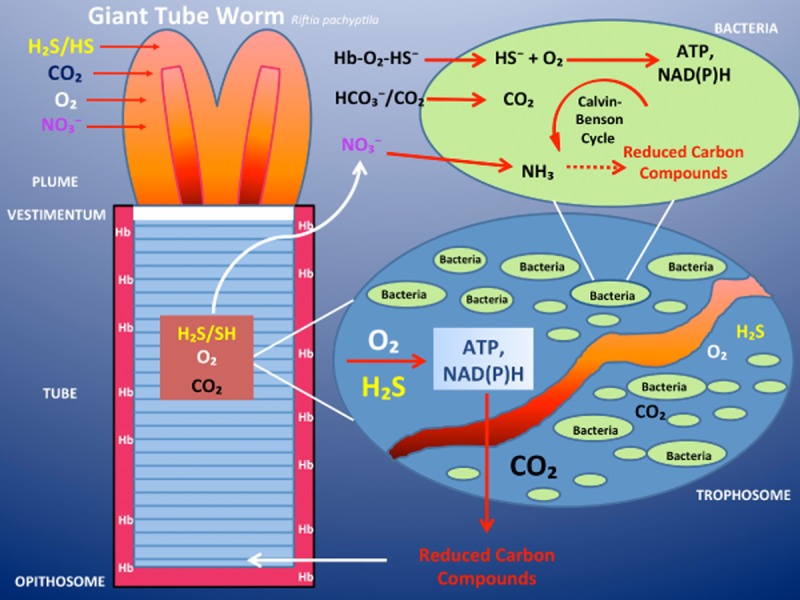

Figure 5.

H2S is a source of energy for the tubeworm living in the oxygen-poor but sulfide-rich environment of deep-sea hydrothermal vents. Schematic illustration of the anatomical and physiological organization of the vestimentiferan tubeworm Rijiia pachypeila. The animal is anchored inside its protective tube by the vestimentum. At its anterior end is a respiratory plume. Behind the vestimentum is a region that makes up the bulk of the worm, the trunk. Inside the trunk is the trophosome, which consists primarily of symbiont containing bacteriocytes, associated cells and blood vessels. At the posterior end of the worm is a short region (opisthosome), which anchors the base of the worm to its tube. Oxygen, sulfide (most likely in the form of HS−), nitrate and carbon dioxide are absorbed through the plume and transported in the blood to the cells of the trophosome. Sulfide, such as oxygen, is bound to the sulfide-binding protein, the worm's haemoglobin, and carried to the symbionts. These tubeworm haemoglobins are capable of carrying oxygen in the presence of sulfide, without being ‘poisoned’ by it. The symbionts oxidize the sulfide and use some of the energy released to drive the Calvin-Benson cycle of net CO2 fixation. Some fraction of the reduced carbon compounds synthesized by the symbionts is translocated to the animal host. Furthermore, the chemosynthetic bacteria within the trophosome are able to convert nitrate to ammonium ions, which then become available for the production of amino acids by the bacteria. Later these organic nitrogen-containing compounds are also released to the tubeworm. Modified after Gaill (1993).