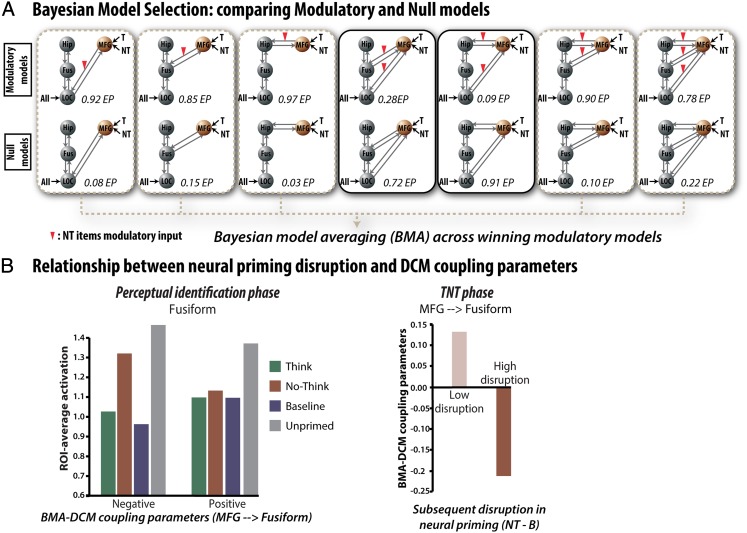

Fig. 4.

Effective connectivity underlying the suppression of visual memories, and its impact. (A) Potential connectivity from MFG during suppression, and its modulation. Fourteen DCMs remained after model family selection (Fig. S2). DCMs included (Upper) or did not include (Lower) top-down modulation of activity during no-think trials (red triangles) originating from the MFG, affecting either the left hippocampus, fusiform gyrus, or the LOC or a combination of these regions. Model exceedance probabilities (EPs) comparing the modulatory and nonmodulatory families separately for each modulated site are displayed below each model. BMA was applied to extract and weight coupling parameters for each connection among the successful modulatory models. (B) Relationship between modulatory parameters for the MFG→fusiform model and disrupted neural priming for no-think items (i.e., no-think − baseline). (Left) Fusiform activation during perceptual identification for participants with low and high negative modulation during the TNT task (n = 12 in each group). (Right) The modulatory parameters for participants with either a low or high reduction of neural priming (n = 12 in each group). These findings indicate that the MFG is negatively coupled with the visual cortex during memory suppression, and, importantly, that the degree of negative coupling predicts disruptions in neural priming for suppressed objects during the later perceptual identification task (see also Fig. S3).