Abstract

Background and Purpose:

Endovascular strategies provide unique opportunity to correlate angiographic measures of collateral circulation at the time of endovascular therapy. We conducted systematic analyses of collaterals at conventional angiography on recanalization, reperfusion and the clinical outcomes in the endovascular treatment arm of the Interventional Management of Stroke (IMS) III Trial.

Methods:

Prospective evaluation of angiographic collaterals was conducted via central review of subjects treated with endovascular therapy in IMS III (n=331). Collateral grade prior to endovascular therapy was assessed with the ASITN/SIR scale, blinded to all other data. Statistical analyses investigated the association between collaterals with baseline clinical variables, angiographic measures of recanalization, reperfusion and clinical outcomes.

Results:

Adequate views of collateral circulation to the ischemic territory were available in 276/331 (83%) subjects. Collateral grade was strongly related to both recanalization of the occluded arterial segment (p=0.0016) and downstream reperfusion (p<0.0001). Multivariable analyses confirmed that robust angiographic collateral grade was a significant predictor of good clinical outcome (mRS≤2) at 90 days (p=0.0353), adjusted for age, history of diabetes, NIHSS strata, and ASPECTS. The relationship between collateral flow and clinical outcome may depend on the degree of reperfusion.

Conclusions:

More robust collateral grade was associated with better recanalization, reperfusion, and subsequent better clinical outcomes. These data, from the largest endovascular trial to date, suggest that collaterals are an important consideration in future trial design.

Keywords: Collateral circulation, recanalization, reperfusion, angiography, stroke

Introduction

The degree of collateral circulation to offset impaired blood flow downstream from an arterial occlusion is a principal determinant of ischemic severity in acute stroke.1 The severity and duration of such ischemia mitigated by collateral perfusion influences tissue injury and clinical impairment. In endovascular approaches to treatment of acute ischemic stroke, the amount of collateral perfusion may be associated with the likelihood of recanalization, or opening of an arterial occlusion, and the extent of reperfusion, or restoration of normal blood flow, into the reopened arterial territory.2 The clinical outcomes of stroke patients treated with endovascular therapies, however, may not always be accurately predicted from the degree of arterial recanalization or reperfusion. Successful revascularization is also not synonymous with subsequent clinical function, as baseline collaterals may determine tissue viability or even hemorrhagic transformation.3 Conventional angiography provides maximal spatial and temporal resolution for depiction of the anatomical and functional capacity of collaterals.4 Endovascular strategies provide a unique opportunity to correlate definitive angiographic measures of collaterals at the time of interventional therapy.

We conducted a systematic evaluation of collaterals on conventional angiography in the endovascular subjects of the Interventional Management of Stroke (IMS) III Trial being treated with intra-arterial (IA) t-PA and/or mechanical thrombectomy subsequent to intravenous (IV) t-PA. The primary objective was to establish an association between the degree of collaterals before endovascular therapy and the likelihood of recanalization, reperfusion, and good clinical outcome at 90 days after randomization.

Methods

Evaluation of angiographic collaterals immediately prior to endovascular treatment was conducted via central review of all endovascular subjects in IMS III. Detailed aspects of trial design and the clinical outcomes of the IMS III trial have already been published elsewhere.5 For every subject treated with endovascular therapy, the complete cerebral angiography study was submitted in digital format for central review. The digital images were reviewed in a DICOM viewer. Although not pre-specified as part of the angiography procedure or data extraction for primary analyses, blinded evaluation of collaterals was conducted by a central angiography reviewer in the multicenter trial. The central adjudicator had extensive experience in grading collaterals in several other multicenter endovascular studies. All diagnostic runs were evaluated for the presence of adequate information regarding collateral circulation with respect to the arterial occlusive lesion (AOL). As collateral injections were not mandated as part of trial protocol, variability was noted from case to case in the completeness of such information. Collateral grades prior to endovascular treatment were assessed with the ASITN/SIR scale on angiography, blind to all other data.6 The ASITN/SIR grading system is a 5-point scale: with 0=no collaterals visible to the ischemic site; 1=slow collaterals to the periphery of the ischemic site with persistence of some of the defect; 2=rapid collaterals to the periphery of the ischemic site with persistence of some of the defect and to only a portion of the ischemic territory; 3=collaterals with slow but complete angiographic blood flow of the ischemic bed by late venous phase; and 4=complete and rapid collateral blood flow to the vascular bed in the entire ischemic territory by retrograde perfusion. Use of this grading system and scale metrics have been previously reported.7 Cases with insufficient information regarding collateral status prior to treatment were excluded from subsequent analyses.

The two central angiography core lab reviewers for the trial independently evaluated angiographic measures of recanalization and reperfusion. Recanalization of the target arterial occlusive lesion was scored with the AOL score.7 Reperfusion of the corresponding arterial territory was scored with the modified Thrombolysis in Cerebral Infarction (mTICI) scale, using 50% as the threshold for achieving reperfusion grade 2b or higher.8 At completion of the trial, these independent assessments were adjudicated by consensus readings, referring to the pre-specified angiography interpretation protocol for the trial.

Since baseline (obtained immediately prior to endovascular treatment but after IV tPA) and target collateral scores were highly associated (kappa=0.96), only baseline collateral score was used in analysis. Collateral score was treated as a categorical variable. Association of collateral grade with baseline characteristics and vascular and clinical outcomes was assessed via Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables. In addition, the Cochran-Armitage trend test (CA) was performed for vascular and clinical outcomes when association with collateral grade was found. Baseline characteristics included comorbid conditions, demographics, and location and severity of stroke. Vascular outcomes were angiographic recanalization, defined as AOL score of 2 or 3, and angiographic reperfusion, defined as mTICI of 2a, 2b, or 3 and separately as 2b or 3. Clinical outcomes considered were symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage within 30 hours of IV t-PA initiation, death from all causes within 90 days, and functional independence at 90 days, defined as a modified Rankin Scale (mRS) of 0, 1, or 2. Day 90 mRS, the primary clinical outcome for IMS III, was imputed as >2 if the assessment was not completed or was completed out of window (before 60 or after 120 days post-randomization).

Logistic regression was used to model outcome as a function of collateral score and covariates selected using backward selection methodology. Baseline variables potentially associated with outcome (p<0.2) were considered for inclusion in the model. For continuous covariates, linearity in the logit was assessed via Box-Tidwell transformation. After establishing that collinearity was not a concern, significant (p<0.05) variables were included in final logistic models. In cases where the Hosmer-Lemeshow test suggested lack of fit, interaction terms were considered. The significance (p<0.05) of baseline collateral score as a predictor of outcome was assessed, and odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals were estimated for each change in collateral score (e.g. 0 to 1, 1 to 2).

Results

From 2006-2012, we evaluated 331 subjects treated with endovascular therapy and available imaging for angiographic collateral grade, of 434 in the endovascular arm. Adequate views of collateral circulation to the ischemic territory were available in 276/331 (83%) subjects. Collateral grade included 19 (6.9%) with grade 0 (no collaterals), 53 (19.2%) with grade 1, 108 (39.1%) with grade 2, 88 (31.9%) with grade 3 and only 8 (2.9%) with grade 4.

Collateral status at angiography was analyzed based on demographics, co-morbidities and other baseline clinical data in IMS III (Table 1). Interestingly, time interval from stroke onset to initiation of IV t-PA differed by collateral grade (p=0.0039); this time was numerically longest for grade 0 subjects (mean 146.9 min, SD 26.3) and shortest for grade 1 subjects (113.2 min, SD 35.8). History of hypertension (p=0.0008) and history of congestive heart failure (p=0.0411) were associated with poorer baseline collateral grade. A trend was noted between the severity of ASPECTS score on pre-IV t-PA brain imaging and collateral grade, where more robust collaterals were noted in those with higher ASPECTS. Supplemental Table I details the relationship between collateral grade and site of initial vascular occlusion. Inadequate power due to limited sample size limited further conclusions, as the numbers become far smaller when one analyzes based on specific occlusion sites.

Table 1.

Baseline Clinical Variables and Relationship with Angiographic Collateral Grade.

| Baseline Variable | Collateral Grade | p-value* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 (n=19) | 1 (n=53) | 2 (n=108) | 3 (n=88) | 4 (n=8) | |||

| Age (yrs), median (min-max) | 71 (61-81) | 64 (33-83) | 68 (23-83) | 69 (24-82) | 64 (43-78) | 0.2790 | |

| Sex, no. (%) | Female | 11 (58) | 23 (43) | 63 (58) | 49 (56) | 3 (38) | 0.3678 |

| Male | 8 (42) | 30 (57) | 45 (42) | 39 (44) | 5 (63) | ||

| Ethnic group, no. (%) | Hispanic or Latino | 1 (5) | 2 (4) | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0.3562 |

|

Not Hispanic/Not

Latino |

17 (89) | 51 (96) | 104 (96) | 82 (93) | 8 (100) | ||

| Unknown | 1 (5) | 0 (0) | 2 (2) | 5 (6) | 0 (0) | ||

| Race, no. (%) | Asian | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | 1 (1) | 3 (3) | 0 (0) | 0.4139 |

|

Black/African

American/African Canadian |

3 (16) | 7 (13) | 18 (17) | 7 (8) | 0 (0) | ||

|

Native

Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander |

0 (0) | 2 (4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Other | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 3 (3) | 0 (0) | ||

| White | 16 (84) | 43 (82) | 88 (82) | 75 (86) | 8 (100) | ||

| Atrial fibrillation, no. (%) | 9 (47) | 16 (30) | 44 (41) | 33 (38) | 2 (25) | 0.5742 | |

| History of congestive heart failure, no. (%) | 2 (11) | 11 (21) | 11 (10) | 4 (5) | 1 (13) | 0.0411 | |

| History of coronary artery disease, no. (%) | 4 (21) | 14 (26) | 20 (19) | 22 (25) | 1 (13) | 0.7237 | |

| History of diabetes, no. (%) | 3 (16) | 11 (21) | 27 (25) | 18 (20) | 2 (25) | 0.8837 | |

| History of hyperlipidemia, no. (%) | 7 (37) | 29 (55) | 49 (45) | 40 (45) | 3 (38) | 0.6538 | |

| History of hypertension, no. (%) | 19 (100) | 45 (85) | 85 (79) | 55 (63) | 6 (75) | 0.0008 | |

| Current antiplatelet use, no. (%) | 7 (37) | 25 (47) | 40 (37) | 38 (43) | 4 (50) | 0.7086 | |

| Current statin use, no. (%) | 7 (37) | 20 (38) | 41 (38) | 28 (32) | 2 (25) | 0.8742 | |

|

Modified Rankin

scale score, no. (%) |

No symptoms at all | 17 (89) | 46 (87) | 97 (90) | 79 (90) | 6 (75) | 0.5682 |

|

No significant

disability despite symptoms |

1 (5) | 5 (9) | 9 (8) | 5 (6) | 2 (25) | ||

| Slight disability | 1 (5) | 2 (4) | 2 (2) | 4 (4) | 0 (0) | ||

|

Systolic blood pressure† (mm Hg), mean

(SD) |

156.4 (21.5) |

147.7 (21.4) |

147 (20.6) | 144.1 (20.7) | 141.7 (27.6) |

0.2803 | |

| Serum glucose† (mmol/liter), mean (SD) | 7.4 (3.5) | 7.5 (3.3) | 7.2 (2.6) | 7.1 (2.6) | 7.8 (3.9) | 0.9790 | |

|

International normalized ratio†, median

(min-max) |

1 (0.9-1.6) | 1 (0.9-1.4) | 1 (0.9-1.7) | 1 (0.9-1.5) | 1.1 (0.9- 1.5) |

0.1545 | |

| NIHSS, no. (%) | NIHSS≤19 | 11 (58) | 31 (58) | 77 (72) | 64 (73) | 6 (75) | 0.3169 |

| NIHSS≥20 | 8 (42) | 22 (42) | 31 (29) | 24 (27) | 2 (25) | ||

|

Presumptive

location of stroke, no. (%) |

Brainstem / cerebellum | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0.6351 |

| Left hemisphere | 7 (37) | 26 (49) | 59 (55) | 43 (49) | 2 (25) | ||

| Right hemisphere | 12 (63) | 27 (51) | 48 (44) | 43 (49) | 6 (75) | ||

| Unknown/multiple | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | ||

| ASPECTS† no. (%) | ASPECTS 0-7 | 11 (58) | 32 (60) | 48 (44) | 37 (42) | 2 (25) | 0.1525 |

| ASPECTS 8-10 | 8 (42) | 21 (40) | 57 (53) | 49 (56) | 6 (75) | ||

|

Time from stroke onset to start of IV t-PA

(min), mean (SD) |

146.9 (26.3) |

113.2 (35.8) |

125.5 (30.7) |

121.2 (36.3) | 124 (30.4) | 0.0039 | |

Fisher’s Exact Test used for categorical variables, Kruskal-Wallis test used for continuous variables

5 subjects missing ASPECTS, 3 missing INR, 1 missing glucose, 6 missing SBP

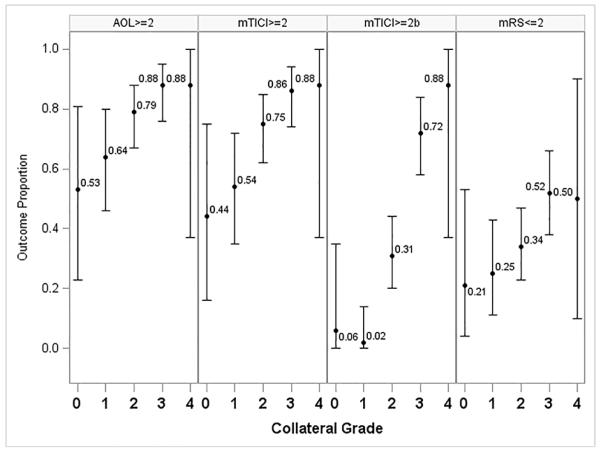

The collateral grade was related to the degree of recanalization, the degree of reperfusion, and clinical outcomes at 3 months in unadjusted (Table 2) and multivariable analyses. Recanalization of the occluded arterial segment (AOL≥2) was more frequent in those subjects with more robust collaterals (p<0.0001), with AOL≥2 recanalization present in only 53% of subjects with no collaterals and in 88% of those with complete collateral filling. Similar analyses revealed that the proportion of cases with downstream reperfusion (mTICI≥2) increases (Figure 1) with more robust collaterals on pre-treatment angiography (CA p<0.0001), with 44% of subjects attaining mTICI≥2 reperfusion at collateral grade 0 and 86% mTICI≥2 reperfusion in subjects with grade 3 collaterals. The proportion of cases with mTICI≥2b reperfusion also increases with more robust collaterals (CA trend test p<0.0001). If we consider variables with significance <0.2 for inclusion in a multivariable model relating collateral score to reperfusion, we consider adjustments for ASPECTS, hypertension, black race, and age. However, after the backward selection procedure, only collateral score remains in the model. As collateral grade increases, so does the proportion of subjects with good clinical outcomes (mRS≤2) at day 90 (CA p=0.0002). Whereas only 21% of those with grade 0 or no collaterals attained good clinical outcomes, more than half of all subjects with complete or grades 3-4 collaterals had good functional outcomes 3 months later. Importantly, all of these subjects with no collaterals and good clinical outcome had distal arterial occlusions, whereas good clinical outcome was never attained in subjects with an ICA or proximal M1 occlusion and absence of collaterals. A trend for higher mortality was noted in those with worse angiographic collaterals (CA p=0.0118) and no relationship could be demonstrated between collaterals and symptomatic hemorrhagic transformation, limited by small numbers of available cases.

Table 2.

Angiographic and Clinical Outcomes Based on Collateral Grade.

| Outcome | Collateral Grade, no. (%) | Fisher p-value |

CA trend p-value |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 (n=19) |

1 (n=53) |

2 (n=108) |

3 (n=88) |

4 (n=8) |

|||

| Recanalization (AOL≥2) | 10 (53) | 34 (64) | 85 (79) | 77 (88) | 7 (88) | 0.0016 | <0.0001 |

| Reperfusion (mTICI≥2)† | 8 (44) | 27 (54) | 79 (75) | 75 (86) | 7 (88) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Symptomatic ICH within 30 hours of IV t-PA | 2 (11) | 3 (6) | 6 (6) | 6 (7) | 0 (0) | 0.8918 | 0.6346 |

| Clinical outcome mRS≤2 at 3 months | 4 (21) | 13 (25) | 37 (34) | 46 (52) | 4 (50) | 0.0039 | 0.0002 |

| Death from all causes within 3 months | 5 (26) | 14 (26) | 21 (19) | 11 (13) | 0 (0) | 0.1402 | 0.0118 |

11 subjects missing mTICI score due to clot location (basilar, vertebral, or PCA)

Figure 1.

Proportion (95% CI) of Vascular and Clinical Outcomes by Collateral Grade.

Collateral score remained significantly associated with recanalization (AOL≥2) and reperfusion (TICI≥2) when adjusted for systolic blood pressure, the only covariate remaining after backward selection. There was a significant interaction between collateral score and baseline systolic blood pressure (SBP) for both vascular outcomes. Due to the complicated relationship between collateral score and SBP with respect to both recanalization and reperfusion, the multivariable model was not used to estimate odds ratios; unadjusted odds ratios are detailed in Table 3. A marginally significant difference was found between subjects with baseline collateral grades of 1 and 2, with subjects with a grade of 2 being 2.07 times (95% CI 1.00-4.27) more likely to achieve (AOL ≥2) recanalization than subjects with grade 1 collaterals. Similar analyses confirmed the association with downstream reperfusion (mTICI≥2). Subjects with grade 2 collaterals were 2.49 times (95% CI 1.23-5.06) more likely to achieve (mTICI≥2) reperfusion than subjects with grade 1 collaterals; subjects with collateral grade 3 were 2.14 times (95% CI 1.01-4.52) more likely to achieve (mTICI≥2) reperfusion than subjects with grade 2 collaterals.

Table 3.

The Association between Collateral grade and Outcome after Endovascular Therapy.

| Recanalization (AOL≥2) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted OR | 95% Wald Confidence Limits | ||

| Collateral grade 1 vs. 0 | 1.61 | 0.56 | 4.65 |

| Collateral grade 2 vs. 1 | 2.07 | 1.00 | 4.27 |

| Collateral grade 3 vs. 2 | 1.89 | 0.87 | 4.14 |

| Collateral grade 4 vs. 3 | 1.00 | 0.11 | 8.92 |

| Reperfusion (mTICI≥2) | |||

| Unadjusted OR | 95% Wald Confidence Limits | ||

| Collateral grade 1 vs. 0 | 1.47 | 0.50 | 4.34 |

| Collateral grade 2 vs. 1 | 2.49* | 1.23 | 5.06 |

| Collateral grade 3 vs. 2 | 2.14* | 1.01 | 4.52 |

| Collateral grade 4 vs. 3 | 1.12 | 0.13 | 9.93 |

| Clinical outcomes (90-day mRS≤2)† | |||

| Adjusted OR | 95% Wald Confidence Limits | ||

| Collateral grade 1 vs. 0 | 0.96 | 0.25 | 3.66 |

| Collateral grade 2 vs. 1 | 1.50 | 0.68 | 3.32 |

| Collateral grade 3 vs. 2 | 2.12* | 1.12 | 4.00 |

| Collateral grade 4 vs. 3 | 0.61 | 0.12 | 3.14 |

p<0.05

Collateral grade, age, history of diabetes, NIHSS strata, and ASPECTS included as covariates in the model

Finally, multivariable analyses confirmed that angiographic collateral grade was associated with good clinical outcome (mRS≤2) at 90 days (p=0.0353), adjusted for age, history of diabetes, NIHSS strata, and ASPECTS. Table 3 shows the adjusted OR for 90-day mRS≤2 for subjects with adjacent baseline collateral grades. A significant difference was noted between subjects with collateral grades of 2 and 3, with grade 3 collateral subjects 2.12 times (95% CI 1.12-4.00) more likely to achieve good clinical outcome than subjects with grade 2 collaterals, adjusted for previously mentioned covariates.

To investigate the effect of reperfusion/recanalization on the relationship between collateral scores and clinical outcome, we also looked at proportions of good clinical outcome by collateral score separately for reperfusers, defined as mTICI≥2, and non-reperfusers, defined as mTICI<2 (and likewise for recanalizers, defined as AOL≥2, and non-recanalizers, defined as AOL<2) via the CA trend test. Due to collinearity concerns arising from the demonstrated association between collateral grade and recanalization/reperfusion, collateral grade and recanalization/reperfusion cannot be included together in a multivariable model. The CA trend test demonstrated a trend in the proportion of good clinical outcome across increasing collateral scores for both reperfusers (Supplemental Figure I) and recanalizers (p=0.0003 and p=0.0009, respectively). There was no evidence of such a trend in non-reperfusers (Supplemental Figure II) and non-recanalizers (p=0.5592 and p=0.6762, respectively).

Discussion

The evaluation of the role of collateral circulation in acute ischemic stroke from the IMS III Trial constitute the largest study to date using the reference standard of conventional angiography.7 Our results provide definitive evidence that collateral status is closely related to revascularization success, defined alternatively as recanalization or reperfusion, and most importantly, clinical outcomes. Collateral grade, measured by the ASITN scale on angiography prior to endovascular therapy, is feasible in the vast majority of cases using routine acquisitions or injections.6

Our findings also confirm that collaterals are an influential factor in the angiographic and clinical outcomes across a diverse population of cases based on site of arterial occlusion and particular endovascular strategies, including local thrombolytic, aspiration, and mechanical thrombectomy approaches in combination with IV t-PA. Prior studies on the impact of collaterals in acute ischemic stroke have largely focused on particular sites of vascular occlusion or alternatively, specific endovascular techniques.9 Recanalization success may be associated with more robust collaterals due to hemodynamic factors, including increased distribution of thrombolytics to the clot surface, potentially making the clot more susceptible to thrombolysis or thrombectomy. Reperfusion of the downstream territory may also be more complete following opening of an arterial occlusion, if such regions are sustained by robust collateral perfusion.

This systematic evaluation of collaterals on conventional angiography provides important data on the relationship with clinical variables commonly encountered in acute stroke. In contrast to recent analyses, we found no significant relationship between age and angiographic collateral grade.10 Similarly, we noted no significant relationship with sex or baseline NIHSS score. These data suggest that collateral status may be difficult to infer based on such brief information during triage of a stroke patient. In fact, our data reveal wide variability in the range of collateral grade without direct links with many clinical factors. We noted a broad distribution of collateral grade, including many cases with partial filling of the territory and very few with rapid, complete collateral perfusion. The potential relationship of collateral grade with history of cardiovascular risk factors like hypertension or congestive heart failure, time from stroke onset to treatment, and ASPECTS score require further study as these variables may exhibit complex interactions. Similarly, the relationship between blood pressure and collateral grade mandates further consideration.

No randomized trial, including the IMS III Trial, has yet to confirm that endovascular therapy can effectively achieve successful outcomes in a broad population of stroke patients.11 However, the relationship of collateral grade with angiographic and clinical outcomes helps inform who is most likely to benefit from endovascular revascularization but also indicates that collateral flow by itself is not enough to guarantee who will benefit from endovascular therapy, at least in the time window of patients treated in IMS III. Increased degree of baseline collateral flow was strongly associated with a good functional outcome in subjects with mTICI≥2 reperfusion but no such relationship was seen in subjects without reperfusion. In subjects with no or minimal collateral flow, 27% of those with reperfusion had a mRS of 0-2 and only 23% of those without reperfusion had good clinical outcomes, although this was largely driven by distal arterial occlusions. Our interpretation is that the degree of collateral flow helps to predict the likelihood of a good outcome with mTICI≥2 reperfusion but the absence of collateral flow should not be used to obviate endovascular therapy. Whether there are similar relationships regarding collateral status with noninvasive imaging techniques such as CT angiography is currently being investigated in the IMS III dataset. Further analyses are needed to discern whether critical thresholds in collateral grade as shown in Table 3 are pivotal and whether the relationship of collaterals with angiographic and clinical outcomes endures in the era of stent-retriever device use.12, 13

Limitations of our study relate to the nature of such subgroup analyses confined to only 83% subjects treated with endovascular therapy and with collaterals evaluated. Although noninvasive imaging selection criteria were not routinely used, selection biases may have influenced collateral status in our sample. Standard angiography acquisitions were prescribed, but not universally adhered to, allowing for variability in image quality and limitations in use of the ASITN/SIR scale. Collateral scoring by an expert rater may also not be indicative of future scale use by a local investigator. The impact of collateral grade may vary by individual site of arterial occlusion (limited in our analyses) or treatment variables not considered such as rehabilitation. Finally, as with any subgroup analyses, caution is advised in the interpretation of statistical significance due to both increased likelihood of false positive test results arising from multiple testing and limited sample sizes.

Conclusions

Collateral circulation was available and evaluated in the largest endovascular therapy trial for stroke conducted to date. More robust collateral grade was associated with better recanalization, reperfusion, and subsequent better clinical outcomes. The role of collaterals in selection criteria or to modify treatment strategies is an important consideration in the design of future endovascular trials.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their gratitude for the efforts of the IMS III Investigators.

Sources of Funding

This work has been funded by NIH-National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke awards (NIH/NINDS) P50NS044378, K24NS072272, R01NS077706, R13NS082049.

IMS III funding included NIH-National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke awards U01NS052220, U01NS054630 and U01NS077304. Genentech Inc. supplied study drug used for intra-arterial t-PA in the endovascular group. EKOS Corp., Concentric Inc., Cordis Neurovascular, Inc. supplied study catheters during Amendments 1-3. In Europe, IMS III investigator meeting support was provided in part by Boehringer Ingelheim.

Footnotes

Clinical Trial Registration-URL: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00359424.

Conflict(s) of Interest/Disclosure(s)

Liebeskind: central angiography reader for IMS III; scientific consultant regarding trial design and conduct to Stryker (modest) and Covidien (modest). He was employed by the University of California (UC), which holds a patent on retriever devices for stroke, at the time of this work.

Tomsick: Co-PI, Interventional OI, Core Lab for Angiography Analysis IMS III.

Foster: received funding from NIH-National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke through MUSC, for her role as unblinded statistician on the IMS III Trial.

Yeatts: received funding from NIH-National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke through MUSC, for her role as unblinded statistician on the IMS III Trial; member of the PRISMS Steering Committee.

Demchuk: consultant to Covidien for speaking engagements.

Jovin: Silk Road Medical – stock ownership.

Khatri: Penumbra Inc – research support to UC, Department of Neurology for her role as Neurology PI of THERAPY Trial; Genentech Inc, research support to UC, Department of Neurology for her role as PI of PRISMS Trial.

Von Kummer: consultant for Lundbeck AC, Penumbra Inc. and Synarc.

Sugg: speaker bureau for Genentech Inc.

Zaidat: consultant for Penumbra, Stryker, Covidien and Microvention.

Goyal: consultant to Covidien-ev3 for trial design, execution and for speaking engagements.

Menon: salary support from Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada; research support (modest) from the Faculty of Medicine, University of Calgary, Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

Broderick: received alteplase from Genentech Inc. for NIH-National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke-funded CLEARER, IMS III trials); $65,000 educational grant to the American Academy of Neurology for 2012 annual meeting program 2AC.007 “What’s in a Stroke Center: Members, Services, Organization and Roles” which he directed. He is a member of the Executive Committee for the PRISMS study research grant. He received catheter devices for IMS III clinical trial from EKOS Corporation and drug for NIH-National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke-funded CLEARER Trial from Schering Plough.

References

- 1.Liebeskind DS. Collateral circulation. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2003;34:2279–2284. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000086465.41263.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bang OY, Saver JL, Kim SJ, Kim GM, Chung CS, Ovbiagele B, et al. Collateral flow predicts response to endovascular therapy for acute ischemic stroke. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2011;42:693–699. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.595256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bang OY, Saver JL, Kim SJ, Kim GM, Chung CS, Ovbiagele B, et al. Collateral flow averts hemorrhagic transformation after endovascular therapy for acute ischemic stroke. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2011;42:2235–2239. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.604603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McVerry F, Liebeskind DS, Muir KW. Systematic review of methods for assessing leptomeningeal collateral flow. AJNR. American journal of neuroradiology. 2012;33:576–582. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A2794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Broderick JP, Palesch YY, Demchuk AM, Yeatts SD, Khatri P, Hill MD, et al. Endovascular therapy after intravenous t-pa versus t-pa alone for stroke. The New England journal of medicine. 2013;368:893–903. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1214300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Higashida RT, Furlan AJ, Roberts H, Tomsick T, Connors B, Barr J, et al. Trial design and reporting standards for intra-arterial cerebral thrombolysis for acute ischemic stroke. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2003;34:e109–137. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000082721.62796.09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zaidat OO, Yoo AJ, Khatri P, Tomsick TA, von Kummer R, Saver JL, et al. Recommendations on angiographic revascularization grading standards for acute ischemic stroke: A consensus statement. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2013;44:2650–2663. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.001972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yoo AJ, Simonsen CZ, Prabhakaran S, Chaudhry ZA, Issa MA, Fugate JE, et al. Refining angiographic biomarkers of revascularization: Improving outcome prediction after intra-arterial therapy. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2013;44:2509–2512. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.001990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wintermark M, Liebeskind DS. Neuroimaging: Introduction. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2013;44:S52. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.680314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Menon BK, Smith EE, Coutts SB, Welsh DG, Faber JE, Goyal M, et al. Leptomeningeal collaterals are associated with modifiable metabolic risk factors. Annals of Neurology. 2013 doi: 10.1002/ana.23906. [published online ahead of print September 4, 2013] http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ana.23906. Accessed November 5, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Chimowitz MI. Endovascular treatment for acute ischemic stroke--still unproven. The New England journal of medicine. 2013;368:952–955. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1215730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nogueira RG, Lutsep HL, Gupta R, Jovin TG, Albers GW, Walker GA, et al. Trevo versus merci retrievers for thrombectomy revascularisation of large vessel occlusions in acute ischaemic stroke (trevo 2): A randomised trial. Lancet. 2012;380:1231–1240. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61299-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pereira VM, Gralla J, Davalos A, Bonafe A, Castano C, Chapot R, et al. Prospective, multicenter, single-arm study of mechanical thrombectomy using solitaire flow restoration in acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2013 doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.001232. [published online ahead of print August 1, 2013] http://stroke.ahajournals.org/strokeasap.shtml. Accessed November 5, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.