Immunoglobulin G4 (IgG4)-related sclerosing disease (ISD) is a condition characterized by elevated serum IgG4 levels and dense IgG4-positive lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates that cause a marked fibrosis of the affected organs. Autoimmune pancreatitis (AIP) is the pancreatic manifestation of ISD, but multiple organs, including the salivary glands, retroperitoneum, kidneys, and biliary tree, can be involved.1 The biliary manifestation of this disease is IgG4-associated cholangitis (IAC), which can present with bile duct lesions that mimic cholangiocarcinomas.2 Distinguishing benign from malignant disease can be particularly challenging in these cases.

Case Report

A woman, age 27 years, presented with a 3-day history of weakness, pruritus, and choluria. Her medical history was significant only for asthma, and her medications included montelukast as needed for treatment of the asthma. She reported a family history of pancreatic cancer (which was diagnosed in a maternal uncle when he was in his fifties) and gastric cancer (which was diagnosed in her mother, who died at age 45 years, possibly because of the gastric malignancy). Initial laboratory analysis revealed an aspartate aminotransferase level of 246 U/L, alanine aminotransferase level of 442 U/L, alkaline phosphatase level of 301 U/L, total bilirubin level of 2.7 mg/dL, direct bilirubin level of 1.7 mg/dL, and amylase level of 564 U/L, with a normal lipase measure. Serologies for hepatitis were negative except for a positive hepatitis B surface antibody. An abdominal ultrasound was initially performed and demonstrated intrahepatic biliary ductal dilation without evidence of a mass or stone. Further evaluation with magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) was suggested. MRCP revealed moderate dilation of the intrahepatic biliary ducts with stricturing of the right and left hepatic ducts as well as an amorphous, heterogeneous signal abnormality at the confluence of the right and left hepatic ducts suggesting a neoplastic process, such as a Klatskin tumor (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

This coronal T2 magnetic resonance image shows dilation of the intrahepatic biliary ducts and an amorphous, heterogeneous signal abnormality at the confluence of the right and left hepatic ducts.

An endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) with cholangioscopy (SpyGlass, Boston Scientific) was performed for further evaluation. A cholangiogram showed strictures in the common hepatic duct and right main hepatic duct with upstream dilation of the right intrahepatic ducts. Cholangioscopy of the strictures in the common hepatic duct demonstrated irregular mucosa with dilated and tortuous vessels and papillary-appearing mucosal projections (Figure 2). The left intrahepatic branches appeared normal. The right hepatic branches could not be visualized cholangioscopically. Cholangioscopic-directed biopsies of the irregular mucosa, brushings for cytology, and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis were performed. Plastic biliary stents were placed into the right and left hepatic ducts across the strictures.

Figure 2.

A SpyGlass cholangioscopy image (right) and endoscopic view (left) showing irregular mucosa with dilated and tortuous vessels and papillary-appearing mucosal projections.

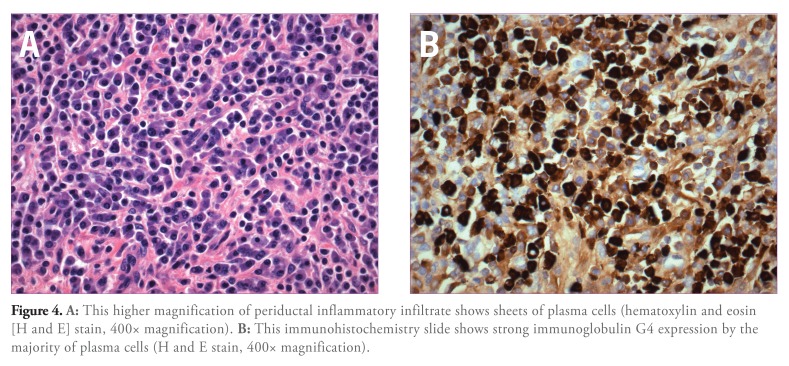

FISH analysis was negative for aneuploidy, and cytology brushings were benign. Biopsy results showed inflammatory findings. Despite these results, the clinical suspicion for a malignancy remained high. The patient underwent right hepatic vein embolization followed by a laparoscopic right hepatectomy. Pathologic examination of the gross specimen revealed near-complete segmental obstruction involving a large bile duct near the resection margin. Marked thickening with accompanying induration of the bile duct wall was also noted in this region. Bile ducts proximal to this area were dilated and also showed variable wall thickening. The liver parenchyma was essentially unremarkable, with no evidence of fibrosis or nodularity. Histopathologic examination revealed marked chronic inflammatory infiltrate around large-caliber bile ducts. The inflammatory infiltrate was most prominent around the area of stricture (Figure 3) and was composed of lymphocytes as well as a large number of plasma cells (Figure 4A). Periductal fibrosis was noted in inflamed areas. Dilated segments of bile ducts also showed intraluminal and intraepithelial neutrophils, which are characteristic of superimposed acute (suppurative) cholangitis. There was no evidence of malignancy. Further evaluation of the inflammatory infiltrate by immunohistochemistry confirmed the presence of a large number of plasma cells (CD138 and IgG-positive), most of which (>80%) expressed IgG4 (Figure 4B). Postoperatively, serum IgG4 levels were checked and were elevated at a value of 168 mg/dL (normal, 21–134 mg/dL).

Figure 3.

A segment of bile duct shows marked periductal chronic inflammation near the area of stricture (hematoxylin and eosin stain, 100x magnification).

Figure 4.

A: This higher magnification of periductal inflammatory infiltrate shows sheets of plasma cells (hematoxylin and eosin [H and E] stain, 400x magnification). B: This immunohistochemistry slide shows strong immunoglobulin G4 expression by the majority of plasma cells (H and E stain, 400x magnification).

Discussion

ISD is a fibroinflammatory disorder that can involve multiple organs, including the salivary glands, lymph nodes, retroperitoneum, kidneys, and biliary tree.1 IgG4 sclerosing cholangitis is an emerging entity that is a part of the spectrum of ISDs. The typical clinical profile of patients with LAG is that of older men who present with obstructive jaundice, increased serum IgG4 levels, AIP, and abundant IgG4-positive plasma cells in the bile duct biopsy specimens.1 Studies have found that past or concurrent AIP or extrabiliary organ involvement is a strong clinical predictor of LAG in patients with biliary strictures.3-5 The diagnosis of AIP is based on the Mayo Clinics HISORt (histology, imaging, serology, other organ involvement, and response to corticosteroid therapy) criteria.6 Various pathologic findings can be found in the liver in patients with AIP, including portal inflammation with or without interface hepatitis, large bile-duct obstructive features, portal sclerosis, lobular hepatitis, and canalicular cholestasis and infiltration of IgG4 plasma cells. These abnormalities can be treated with steroid therapy.7 Hepatic inflammatory pseudotumors with dense lymphoplasmacytic infiltration and obliterating phlebitis also have been previously reported in patients with AIP8 Our patient reported no history consistent with AIP and had no radiologic studies suggestive of this diagnosis.

Distinguishing LAC from malignant disease can be challenging. Previously, investigators found that ERCP alone had a sensitivity of only 45% in diagnosing LAC, and they concluded that additional diagnostic strategies would be necessary to accurately distinguish LAC from primary sclerosing cholangitis or cholangiocarcinoma.9 Additionally, the cholangioscopic appearance of LAC has been reported as smooth, edematous mucosa with a proliferation of dilated and tortuous vessels at the stricture site.10 Our case did not demonstrate these cholangioscopic findings and was more consistent with a malignant stricture with irregular surface mucosa with dilated and tortuous vessels.11 Although the IgG4 level was elevated in this case, an elevated serum IgG4 level alone in the presence of a biliary stricture has not been shown to exclude the diagnosis of cholangiocarcinoma. However, a cutoff of 4 times the upper limit of normal has 100% specificity for the diagnosis of IAC.12 This case highlights the variable presentation of LAC, which should be considered in the differential diagnosis of unexplained biliary strictures. The lack of concurrent AIP should not exclude the diagnosis.

References

- 1.Ghazale A, Chari ST, Zhang L, et al. Immunoglobulin G4-associated cholangitis: clinical profile and response to therapy. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:706–715. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hamano H, Kawa S, Uehara T, et al. Immunoglobulin G4-related lymphoplasmacytic sclerosing cholangitis that mimics infiltrating hilar cholangiocarcinoma: part of a spectrum of autoimmune pancreatitis? Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:152–157. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(05)00561-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nakazawa T, Ando T, Hayashi K, Naitoh I, Ohara H, Joh T. Diagnostic procedures for IgG4-related sclerosing cholangitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2011;18:127–136. doi: 10.1007/s00534-010-0320-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nakazawa T, Naitoh I, Hayashi K, et al. Diagnostic criteria for IgG4-related sclerosing cholangitis based on cholangiographic classification. J Gastroenterol. 2012;47:79–87. doi: 10.1007/s00535-011-0465-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oh HC, Kim MH, Lee KT, et al. Clinical clues to suspicion of IgG4-associated sclerosing cholangitis disguised as primary sclerosing cholangitis or hilar cholangiocarcinoma. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25:1831–1837. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2010.06411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chari ST, Smyrk TC, Levy MJ, et al. Diagnosis of autoimmune pancreatitis: the Mayo Clinic experience. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:1010–1016. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.05.017. quiz 1934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Umemura T, Zen Y, Hamano H, Kawa S, Nakanuma Y, Kiyosawa K. Immunoglobin G4-hepatopathy: association of immunoglobin G4-bearing plasma cells in liver with autoimmune pancreatitis. Hepatology. 2007;46:463–471. doi: 10.1002/hep.21700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kanno A, Satoh K, Kimura K, et al. Autoimmune pancreatitis with hepatic inflammatory pseudotumor. Pancreas. 2005;31:420–423. doi: 10.1097/01.mpa.0000179732.46210.da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kalaitzakis E, Levy M, Kamisawa T, et al. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiography does not reliably distinguish IgG4-associated cholangitis from primary sclerosing cholangitis or cholangiocarcinoma Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011. 9 800 803 e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yasuda I, Nakashima M, Moriwaki H. Cholangioscopic view of IgG4-related sclerosing cholangitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2011;18:122–124. doi: 10.1007/s00534-010-0324-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fukuda Y, Tsuyuguchi T, Sakai Y, Tsuchiya S, Saisyo H. Diagnostic utility of peroral cholangioscopy for various bile-duct lesions. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:374–382. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2005.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oseini AM, Chaiteerakij R, Shire AM, et al. Utility of serum immunoglobulin G4 in distinguishing immunoglobulin G4-associated cholangitis from cholangiocarcinoma. Hepatology. 2011;54:940–948. doi: 10.1002/hep.24487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]