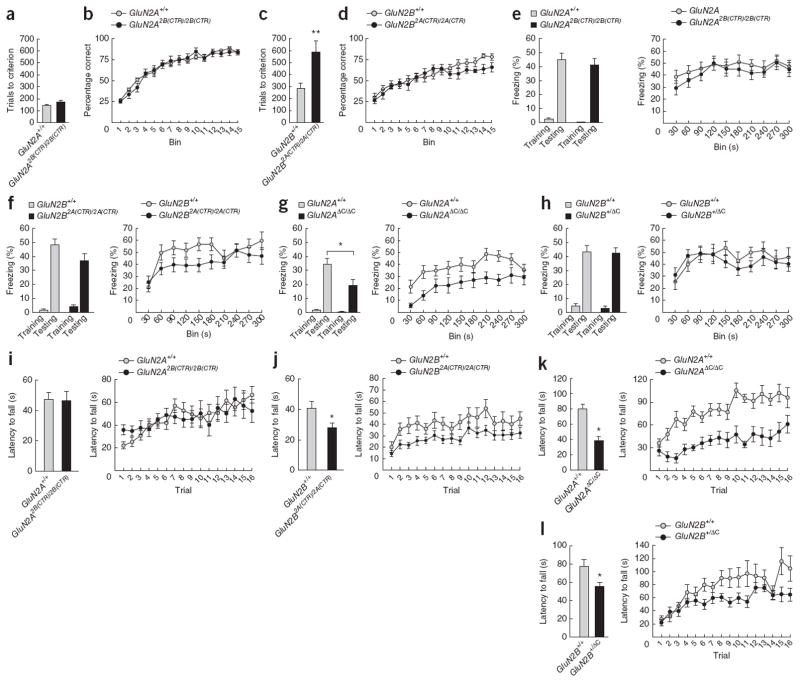

Figure 3.

Learning behavior. (a–d) Perceptual learning and reversal learning in GluN2A2B(CTR)/2B(CTR) and GluN2B2A(CTR)/2A(CTR) mice, as measured by performance in visual discrimination and subsequent reversal learning (percentage correct trials across 15 bins of 30 reversal trials) in a touchscreen operant conditioning task. **P < 0.01. (a) The total number of trials required to reach acquisition criterion was the same for GluN2A2B(CTR)/2B(CTR) mice (n = 9) and GluN2A+/+ controls (n = 11) (t18 = −1.75, p = 0.1). (b) We saw no significant interaction of bin and genotype (F1,13.9 = 153.3, P = 0.1) and no significant main effect (F1,18 = 0.2, p > 0.8) between GluN2A2B(CTR)/2B(CTR) mice and controls. (c) GluN2B2A(CTR)/2A(CTR) mice (n = 8) required significantly more trials to reach criterion than GluN2B+/+ controls (n = 10) (t16 = −3.12, P < 0.01). (d) We saw no significant interaction of bin and genotype (F1,8,2 = 0.68, P > 0.4) and no significant main effect (F1,13 = 1.69, P > 0.2) between GluN2B2A(CTR)/2A(CTR) mice and controls. (e–h) Associative learning in GluN2A2B(CTR)/2B(CTR), GluN2B2A(CTR)/2A(CTR), GluN2AΔC/ΔC and GluN2B+/ΔC mice, as measured by performance in a contextual fear conditioning task. Left, freezing over a 150-s period before unconditioned stimulus presentation (shock) on training day, and for 180 s on testing 24 h after training. Right, freezing over 300 s of testing. There were no significant effects in baseline freezing on training days for any mutant (data not shown). *P < 0.05. (e) GluN2A2B(CTR)/2B(CTR) mice (n = 21) showed equivalent freezing to GluN2A+/+ controls (n = 22) (t41 = 0.43, P = 0.1). (f) GluN2B2A(CTR)/2A(CTR) mice (n = 21) showed equivalent freezing to GluN2B+/+ controls (n = 19) (t38 = 1.7, P > 0.1). (g) GluN2AΔC/ΔC mice (n = 11) showed significantly less freezing than GluN2A+/+ controls (n = 19) (t28 = 2.2, P < 0.05). (h) GluN2BΔC/+ mice (n = 15) showed equivalent freezing to GluN2B+/+ controls (n = 10) (t23 = 0.14, P > 0.8). (i–l) Motor learning and coordination of GluN2A2B(CTR)/2B(CTR), GluN2B2A(CTR)/2A(CTR), GluN2AΔC/ΔC and GluN2B+/ΔC mice, as measured by performance in the accelerated rotarod. Performance was measured as average latency to fall (s) over eight morning trials (1–8) and eight afternoon trials (9–16). Motor learning deficits were determined by significant interactions of trial and genotype for each session. (i) We found no difference in motor coordination between GluN2A2B(CTR)/2B(CTR) mice (n = 20) and GluN2A+/+ controls (n = 21) (F1,39 = 0.01, P > 0.9), but did find a significant interaction of trial and genotype for the first session (trials 1–8) (F7,273 = 2.1, P < 0.05)—although this was due to enhanced performance on initial trials—but not in the second session (trials 9–16) (F5.4,208.7 = 1.5, P > 0.1). (j) GluN2B2A(CTR)/2A(CTR) mice (n = 21) showed impaired motor coordination relative to GluN2B+/+ controls (n = 19) (F1,38 = 5.1, P < 0.05), but an equivalent rate of improvement across both the first (F4.5,171.5 = 0.65, P > 0.6) and second (F7,266 = 0.4, P > 0.9) sessions. (k) GluN2AΔC/ΔC mice (n = 11) showed impaired motor coordination relative to GluN2A+/+ controls (n = 19) (F1,28 = 20.1, P < 0.0001) and showed reduced motor learning for the first session (F7,196 = 2.1, P < 0.05), but not for the second session (F4.6,130 = 0.7, P > 0.5). (l) GluN2B+/ΔC mice (n = 15) showed impaired motor coordination relative to GluN2B+/+ controls (n = 10) (F1,23 = 6.8, P < 0.02) and a nonsignificant trend toward impaired motor learning over both the first (F7,161 = 1.5, P > 0.1) and second (F3.5,80.2 = 1.6, P > 0.1) sessions. All data are mean±s.e.m.