Abstract

Successfully navigating entry into romantic relationships is a key task in adolescence, which sensitivity to rejection can make difficult to accomplish. This study uses multi-informant data from a community sample of 180 adolescents assessed repeatedly from age 16 to 22. Individuals with elevated levels of rejection sensitivity at age 16 were less likely to have a romantic partner at age 22, reported more anxiety and avoidance when they did have relationships, and were observed to be more negative in their interactions with romantic partners. In addition, females whose rejection sensitivity increased during late adolescence were more likely to adopt a submissive pattern within adult romantic relationships, further suggesting a pattern in which rejection sensitivity forecasts difficulties.

Relationship transitions are a feature of adolescence. In particular, transitions into romantic relationships are commonplace during late adolescence (Furman & Winkles, 2012). As a result, worries about rejection during the adolescent years are particularly likely to affect the formation and quality of romantic relationships in late adolescence and early adulthood. There is evidence that who are most sensitive to rejection tend to interpret ambiguous situations as indications of rejection, creating a self-fulfilling prophecy in which they expect rejection and accordingly, elicit it (Downey & Feldman, 1996). This would suggest that rejection sensitive adolescents might be particularly susceptible to developing higher levels of anxiety and overall negativity in their future romantic relationships. Unfortunately, rather little is known about how the developmental course of rejection sensitivity in mid-to-late adolescence is related to the risk for future romantic relationship difficulties. The current study incorporates multi-informant data to test whether initial levels and changes in rejection sensitivity in mid-to-late adolescence are related to psychological, equality, and behavioral aspects of romantic relationships during early adulthood.

The processes involved in creating and fostering rejection sensitivity are best understood by linking relationship experiences to outcome expectancies. The rejection sensitivity model (Downey & Feldman, 1996) builds upon a cognitive-affective processing framework (Mischel & Shoda, 1995) and social information-processing models (Crick & Dodge, 1994). This model states that experiences of rejection within parent and peer relationships create sensitivity for individuals towards the possibility of rejection (Downey, Lebolt, Rincόn, & Freitas, 1998). This sensitivity manifests itself in behaviors within close relationships that are erratic--at times, hostile and aggressive, and at other times distant and submissive--resulting in turbulent and often short-lived relationships (Downey, Frietas, Michaelis, Khouri, 1998; Romero-Canyas, Downey, Berenson, Ayduk, & Kang, 2010).

Those who score high on measures of rejection sensitivity also tend to report greater negativity and a relative increase in behaviors that cede power of the relationship to their partner. Concurrent associations suggest that both adolescents and adults who report elevated levels of rejection sensitivity and their partners report more negativity within their romantic relationship (Downey & Feldman, 1996; Galliher & Bentley, 2010). The processes by which these relationships spiral to low levels of quality are not fully understood. There is concurrent evidence from adolescent romantic relationships, indicating that as a result of being insecure and worrying about rejection, individuals who are rejection sensitive exhibit a rise in self-silencing behaviors (Galliher & Bentley, 2010; Harper, Dickson, & Welsh, 2006), suggesting they suppress their opinions and cede power within the relationship in unhealthy ways. Other studies point to an increase in hostile and aggressive behaviors for adolescents who are rejection sensitive (Romero-Canyas et al., 2010; Mathieson et al., 2011). It is unclear whether these patterns extend into the adult years, but the consistent concurrent connection between rejection sensitivity and poor quality relationships across these studies suggests the potential existence of an enduring negative pattern.

Late adolescence is a period that involves many transitions, among them the emergence of romantic relationships. A growing body of literature suggests that the patterns an individual displays within their adolescent romantic relationships are indicative of the patterns seen in adulthood (Madsen & Collins, 2011; Welsh, Grello, & Harper, 2003). As a result, the negative patterns and perceptions that an individual develops can have lasting impacts not only on their success in relationships, but also on their overall mental health (Marston, Hare, & Allen, 2010). Further, while many youth have not had any experience with romantic relationships in early-to-mid adolescence, data suggests that by 16 years of age, the majority of individuals have had a romantic relationship in the prior 18 months (Carver, Joyner, & Udry, 2003; Collins, 2003).

It is within this period of late adolescence that individuals solidify a core self or internal working model that guides them in their interaction within close relationships. In terms of romantic relationships, this is perhaps best summed up by the statement that, “it’s not just who you’re with, it’s who you are” (Robins, Caspi, & Moffitt, 2002). In other words, the perceptions an individual prescribes to in response to their relationship experiences, like rejection sensitivity, may serve as predictors of that individual’s behavior and functioning within future relationships (Donnelan, Larsen-Rife, & Conger, 2005; Neyer & Asendorpf, 2001). Thus, it seems probable that the initial level of rejection sensitivity and development (change) in rejection sensitivity an adolescent reports in mid-to-late adolescence, a period in which they are gaining romantic relationship experiences, should forecast their future experience with romantic relationships. Rejection sensitivity at age 16 is likely to forecast internal anxiety and turmoil about romantic relationships, as adolescents who have higher worries over potential rejection may be more likely to exhibit patterns of reluctance concerning dating initiation and functioning (London, Downey, Bonica, & Paltin, 2007), although this has not been directly tested. Similarly, increase in rejection sensitivity during late adolescence may alter the behavior of individuals in their relationships, potentially leading to the rise of maladaptive relationship maintenance behaviors.

There is also evidence to suggest that males and females display different patterns of rejection sensitivity and processes surrounding rejection sensitivity. Previous research suggests that males may have more difficulty and experience greater worries over rejection when adapting to cross-sex friendships and eventually to romantic relationships than females (London, Downey, Bonica, & Paltin, 2007; Zimmer-Gembeck, Siebenbruner, & Collins, 2001), though lack of longitudinal data in late adolescence leaves our understanding of this development unclear. It may also be that males and females handle their insecurities concerning rejection within relationships by adopting somewhat different coping strategies. For example, recent work has suggested that females who are rejection sensitive are more likely than males to adopt submissive coping strategies that maintain relationships (Rose & Rudolph, 2006; Smith, Welsh, & Fite, 2010). This may be particularly true when females that increase in worries about rejection also have insecurities about their romantic relationships during late adolescence (Seiffge-Krenke, 2011; Volz & Kerig, 2010). Increasing worries may be the result of repeatedly experiencing tumultuous relationships, and thus the development of maladaptive behaviors like submissive coping become more commonplace. The current study builds from these studies by utilizing longitudinal data to link changes in rejection sensitivity to relative power in future romantic relationships. Self-reports of relative power as well as romantic partner reports of relative power are included to determine if it is a pattern that both partners agree about.

Although there is little longitudinal research on rejection sensitivity to evaluate the ways in which it changes over time, it is hypothesized that rejection sensitivity may peak in adolescence (London, Downey, Bonica, & Paltin, 2007; Masten, Telzer, Fuligni, Lieberman, & Eisenberger, 2012). The current study fills this gap by utilizing multi-informant longitudinal data spanning the transition from adolescence into the early adult years. This longitudinal study uses adolescent reports to assess both initial levels and change in rejection sensitivity across midto- late adolescence. This initial level at age 16 and the change from age 16 to 19 is then used to predict romantic relationship status, along with psychological (anxiety and avoidance), equality (relative power), and behavioral (observed negativity) aspects within romantic relationships in early adulthood. Two overarching hypotheses were tested. First, we hypothesized that higher initial levels of rejection sensitivity at age 16 would predict a lower likelihood of having a romantic relationship in early adulthood. Second, we hypothesized that for those individuals who did have romantic relationships in adulthood, both initial levels and the direction of change in rejection sensitivity in adolescence would predict their behavior within the relationship, such that those with elevated levels of rejection sensitivity would display more anxiety, avoidance, negativity, and less relative power in their romantic relationships. We also assessed the extent to which gender might moderate the link between rejection sensitivity and romantic outcomes in all analyses.

Method

Participants

This report is drawn from a larger longitudinal investigation of adolescent social development in familial and peer contexts. Participants included 180 teenagers (84 males and 96 females) assessed over a six-year period from ages 16 to 22. The sample was racially/ethnically and socioeconomically diverse: 58% of participants identified themselves as Caucasian, 29% as African American, 1% as Hispanic/Latino, and 12% as being from other or mixed ethnic group. Target adolescents’ parents reported a median family income in the $40,000–$59,999 range (13% of the sample reported annual family income less than $20,000 and 37% reported annual family income greater than $60,000.

Target adolescents first completed questionnaires yearly at four time points in mid-to-late adolescence, from ages 16.35 (SD = 0.87) to 19.64 (SD = 1.06). These target individuals were assessed again in early adulthood (M age = 21.66, SD = 0.96), this time with their romantic partners (n = 117).

Measures

Rejection Sensitivity

Target teenagers’ level of rejection sensitivity was assessed annually between ages 16 to 19 using the extensively validated Rejection Sensitivity Questionnaire (RSQ; Downey & Feldman, 1996). The measure consists of 18 hypothetical situations in which rejection by a significant other is possible (e.g., “You ask a friend to do you a big favor”). For each situation, participants were first asked to indicate their degree of concern or anxiety about the outcome of the situation (e.g., “How concerned or anxious would you be over whether or not your friend would want to help you out?”) on a 6-point scale ranging from 1 (very unconcerned) to 6 (very concerned). Participants were then asked to indicate the likelihood that the other person would respond in an accepting manner (e.g., “I would expect that he/she would willingly agree to help me out”) on a 6-point scale ranging from 1 (very unlikely) to 6 (very likely). An overall rejection sensitivity score for each situation was obtained by weighting the expected likelihood of rejection by the degree of anxiety or concern about the outcome of the request. The rejection sensitivity score (Overall M = 7.99, SD = 2.93, Range = 1.22 – 17.80) used in analyses was computed by summing the expectation of rejection by concern ratings for each situation and then dividing by the total number of situations. Internal consistency was excellent (α = .87 – .92).

Romantic Relationship Status

In early adulthood, (M age = 21.66), participants were asked to report if they currently had a significant romantic relationship (i.e. 2 months or longer). Of the 180 participants, 117 answered yes and their relationships with target adolescents averaged 14.40 months (range = 2.00 – 64.00, SD = 13.31).

Avoidance and Anxiety in Romantic Relationships

Target participants completed the Multi-Item Measure of Adult Romantic Attachment (Brennan, Clark & Shaver, 1998; Bartholomew, 1990) in young adulthood (M age= 21.66, SD= .96). From this 36-item measure, two psychological factors, anxiety and avoidance in romantic relationships, were analyzed. The format for this measure asked participants how they generally felt in romantic relationships, not just in the current relationship. Items were scored on a 7-point scale, ranging from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 7 (Strongly Agree), with lower scores reflecting lower levels of anxiety and avoidance in romantic relationships. Sample items include questions such as, “I get uncomfortable when a romantic partner wants to be very close,” and “I do often worry about being abandoned.” The scales demonstrated good reliability (α = .94 – .95).

Relative Power in Romantic Relationships

Both target adolescents and their romantic partners completed the Relative Power scale from the Network of Relationships Inventory (Furman & Buhrmester, 1985) in young adulthood. The measures included items such as, “In your relationship with this person, how much do you tend to take charge and decide what should be done?” The scale ranged from 1 (Never/Not at all) to 5 (Extremely much) and scores were calculated such that higher scores indicated that the target adolescent was less submissive in their relationship. The scale demonstrated good reliability (α = .82 – .84). The correlation between partners was moderate (r = .22).

Observed Negativity in Romantic Relationships

In early adulthood, target adolescents and their romantic partners participated in a revealed differences task in which they discussed an unresolved issue in their relationship that they had individually identified as a topic of disagreement. Before the discussion began, an interviewer made an audio recording of the target participant stating the problem, his or her perspective on the problem, and what the participant believed his or her romantic partner’s perspective was. The romantic partner was then brought into the room to discuss the problem for eight minutes, and the interaction was videotaped. After the interview was over, the discussions were transcribed.

Two coders then separately used both the transcript and videotape to code each interaction. The coding system was based on a system developed by Grotevant and Cooper (1985) to assess negotiation of autonomy and relatedness in interpersonal interactions. The coding system employed yields ratings for the target participant’s overall behavior towards their romantic partner during the interaction. Ratings are molar in nature; however, these molar scores are derived from an anchored coding system that considers both the frequency and intensity of each speech relevant to that behavior during the interaction in order to assign an overall molar score. Specific interactive behaviors were coded, and then summed together on a priori grounds. For this study, summary scores of participant’s negative displays of autonomy (e.g. “whatever I don’t care that much, I don’t want to talk about it“) and relatedness (e.g. “I can’t believe you’d say that, that’s really stupid”) were utilized. Resulting scores ranged from 0 to 4, with higher scores indicating greater frequency and intensity of behaviors that undermine autonomy and relatedness (Negativity). The two coders were blind to other data from the study, and their ratings were found to be reliable (ICC = .76), considered in the good to excellent range (Cicchetti & Sparrow, 1981).

Procedure

Adolescents were initially recruited to participate in a larger study from the seventh and eighth grades at a public middle school drawing from suburban and urban populations in the southeastern United States. Students were recruited via an initial mailing to all parents of students in the school along with follow-up contact efforts at school lunches. Between ages 16 to 19, adolescents were mailed questionnaires, and asked to fill the questionnaires out about themselves. Additionally, in early adulthood (M age = 21.66), target participants came in with their romantic partners and participated in an eight-minute videotaped revealed differences interaction, as described above. Target adolescents and their romantic partners were also asked to fill out questionnaires about the characteristics of themselves, their romantic partner, and their relationship with each other. Adolescents and their romantic partners were each compensated $100.

Of the 180 individuals who provided data on rejection sensitivity between ages 16 and 19, 65% (n = 117) reported having a romantic partner and completed reports about their relationship in early adulthood, while the other 63 reporting not having a significant romantic relationship. Of these 117 individuals, 2 described their relationships as homosexual. Data was also available from 95% (n = 111) of the identified romantic partners and observations were conducted for 79% (n = 92) of the couples. All interviews took place in a university academic building, within private offices. Participants’ data were protected by a Confidentiality Certificate issued by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, which further protects information from subpoena by federal, state, and local courts. If necessary, transportation and child care were provided for participants.

Missing Data

All analyses were conducted in MPLUS 6.12 (Muthén & Muthén, 2010). To best address any potential biases due to attrition in longitudinal analyses, full information maximum likelihood methods were used with analyses. These procedures have been found to yield the least biased estimates when all available data are used for longitudinal analyses (Enders, 2001). Thus, the entire original sample of 180 was utilized for the initial growth analyses, as missing data was minimal at each of the time points (less than 15%). For every analysis, alternative analyses using just those adolescents without missing data (i.e., listwise deletion) yielded results that were substantially identical to those reported below. In sum, analyses suggest that attrition was modest overall and not likely to have distorted any of the findings reported.

Results

Initial Levels and Rate of Change in Rejection Sensitivity from Age 16 to 19

The initial analysis was conducted to determine if there was variation in both initial levels of rejection sensitivity at age 16, and whether there was variation in the amount of change from age 16 to age 19. To accomplish this, a growth curve model for the four available time points of rejection sensitivity was examined. Intercept loadings were set at 1 and slope loadings were set at fixed linear intervals, with the intercept and slope allowed to covary. This linear growth model fit the data well (CFI = .99; RMSEA = .05; SRMR = .04). Table 1 describes the correlations among rejection sensitivity at the four time points (age 16–19) and the means and variances for the intercept and slope parameters for the rejection sensitivity growth model. The linear slope results indicate that on average rejection sensitivity decreased over time. Further, there was significant variance in both the intercept and the slope suggesting that individuals start at different levels and exhibit different patterns of change. We also ran a multiple group model to determine if gender moderated these findings. There was evidence that males (M = 9.05, SD = 3.43) were more rejection sensitive than females (M = 7.91, SD = 3.53) initially, F (1, 178) = 4.31, p = .04. There were no gender differences in the rate of change.

Table 1.

Rejection Sensitivity Associations and Growth Parameters From Age 16–19

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Rejection Sensitivity Age 16 | - | |||||||

| 2. Rejection Sensitivity Age 17 | .21* | - | ||||||

| 3. Rejection Sensitivity Age 18 | .19* | .17* | - | |||||

| 4. Rejection Sensitivity Age 19 | .02 | .05 | .30* | |||||

| Growth Parameters | ||||||||

| Intercept | Slope | |||||||

| M | SE | Variance | SE | M | SE | Variance | SE | |

| Rejection Sensitivity | 8.22* | (0.27) | 9.47* | (1.42) | −0.36* | (0.08) | 0.33* | (0.18) |

Note.

p < .05.

p < .01

Predicting Adult Romantic Relationship Functioning from Adolescent Rejection Sensitivity

The main analyses used the intercept (initial level at age 16) and slope (change from age 16 to age 19) factors from the rejection sensitivity growth model to predict romantic relationship outcomes at age 22. In all analyses, multiple group models utilizing a chi-square difference test were tested to determine if gender moderated any effects.

Predicting Romantic Relationship Status

We hypothesized that initial levels at age 16 and change in rejection sensitivity from age 16–19 would predict the likelihood of having a romantic relationship at age 22. Results presented in Table 2 indicate a significant association between greater rejection sensitivity at age 16 and a decreased likelihood of having a romantic relationship at age 22. The association between change in rejection sensitivity and relationship status was not significant (β = −.09). Gender did not moderate this finding.

Table 2.

Adolescent Rejection Sensitivity Predicting Early Adult Romantic Partner Status and Perceptions of Anxiety and Avoidance in Romantic Relationships

| Romantic Partner Status | Self-Reported Anxiety | Self-Reported Avoidance | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rejection Sensitivity at Age 16 | |||

| β (SE) | −.28* (.13) | .43* (.11) | .33* (.12) |

| CI | [−.49, −.07] | [.25, .61] | [.14, .52] |

| Change in Rejection Sensitivity (Age 16–19) | |||

| β (SE) | .06 (.22) | .13 (.16) | .14 (.18) |

| CI | [−.26, .37] | [−.10, .34] | [−.12, .41] |

Note.

p < .05.

p < .01.

All participants were included in this analysis. Those individuals who did not have a current romantic partner (n = 63), reported on their anxiety and avoidance from their most recent relationship. The presence or absence of a current relationship did not moderate any of these associations.

Predicting Romantic Relationship Behavior

We hypothesized that initial levels and the direction of change of rejection sensitivity in adolescence would predict three domains of an individual’s participation in adult romantic relationships: psychological (anxiety and avoidance), equality (relative power), and behavior (observed negativity). Models were run separately in order to gauge the independent prediction of each piece of romantic relationship functioning. The findings are summarized in Tables 2 and 3.

Table 3.

Adolescent Rejection Sensitivity Predicting Observed Positive and Negative Interaction, and Reported Relative Power Within Early Adult Romantic Relationships

| Observed Negativity in the Relationship | Relative Power in the Relationship | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Self-Report | Partner-Report | ||

| Rejection Sensitivity at Age 16 | |||

| β (SE) | .28* (.11) | −.21 (.16) | −.25 (.17) |

| CI | [.02, .54] | [−.46, .04] | [−.56, .05] |

| Change in Rejection Sensitivity (Age 16–19) | |||

| β (SE) | .15 (.18) | −.34* (.13) | −.26* (.12) |

| CI | [−.05, .35] | [−.59, −.08] | [−.51, −.01] |

Note.

p < .05.

Only participants who reported being in a romantic relationship at the time of data collection were involved in this analysis (n = 117).

Predictions from initial levels of rejection sensitivity

The intercept of rejection sensitivity predicted future romantic relationship behavior in two of the three domains. The intercept significantly predicted future self-reports of anxiety and avoidance in romantic relationships, such that adolescents who reported more rejection sensitivity at age 16 reported more anxiety and avoidance in their relationships in early adulthood (see Table 2). Further, the intercept significantly predicted the observed negativity of interactions with romantic partners, such that adolescents who reported more rejection sensitivity at age 16 were observed to have more negativity in their early adult relationships (see Table 3). Gender did not moderate these findings.

Predictions from change over time in rejection sensitivity

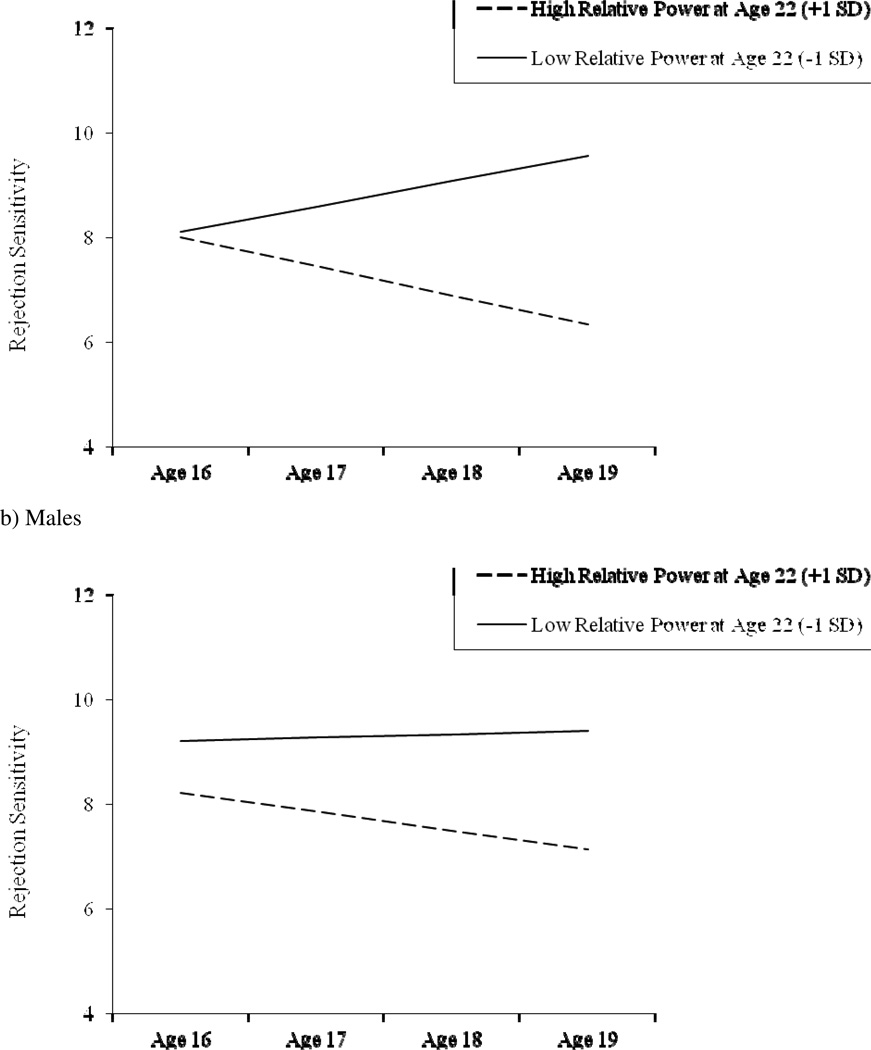

The slope of rejection sensitivity from age 16 to 19 predicted future romantic relationship behavior in one of the three domains. Change in rejection sensitivity significantly predicted future self-and romantic partner reports of relative power within the relationship, such that adolescents who experienced relative increases in rejection sensitivity during late adolescence were more submissive within their early adult romantic relationships (see Table 3). Gender moderated this effect for self-reports only, Δχ2 (1) = 4.01, p = .04, such that the association was stronger for females (β = −.45) than for males (β = −.21). This effect is depicted for females and males in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Estimated Change From Age 16 to 19 in Rejection Sensitivity as a Function of Age 22 Self-Report of Their Relative Power Within a Romantic Relationship.

Discussion

The findings are consistent with the notion that elevated levels of rejection sensitivity during initial romantic relationship experiences are associated with poorer future relationship functioning. This study also points to two instances in which rejection sensitivity may be linked to future romantic relationship outcomes. First, adolescents, both males and females, who initially had elevated levels of rejection sensitivity at age 16 were more likely to have problematic relationship profiles 6 years later in early adulthood. They were less likely to have romantic relationships, more likely to report feeling anxious and avoidant when they did have relationships, and were observed to be more negative in their interactions with romantic partners. Second, adolescents, particularly females, who exhibited a pattern of increasing worries about rejection during late adolescence, were more likely to report adopting a submissive pattern of behavior within their early adult romantic relationships. This latter finding may be of particular importance as it may serve as a marker for relationship violence.

The findings of this study are noteworthy in that they point to the future relationship consequences of experiencing worries about rejection during adolescence. More worries about rejection at age 16 were associated with a lower likelihood of having a romantic partner at age 22. While other studies have suggested concurrent associations between romantic partner status and rejection sensitivity in early adulthood (Levy, Ayduk, & Downey, 2001), this is the first study to establish a long-term association. This is substantial as failing to initiate romantic relationships in early adulthood is a marker for unhealthy development (Donnelan et al., 2005). Initial levels of rejection sensitivity at age 16 also predicted an array of indicators associated with problematic romantic relationship functioning in early adulthood including anxiety, avoidance, and negativity within the relationship. These findings lend to the claim that adolescents who have elevated levels of rejection sensitivity are more likely to have both psychological difficulties with relationships and elevated levels of negativity within relationships. The elevated levels of adult anxiety and avoidance appear consistent with prior adolescent fears over rejection. It is surprising that only age 16 levels of rejection sensitivity, and not changes from age 16 to age 19, are related to these struggles. It may be that the initial level of rejection sensitivity is more a reflection of first romantic relationship impressions. There is evidence suggesting that more intentionally coded impressions, as would likely be the case with early romantic relationship experiences, support the encoding and longevity of these impressions (Gilron & Guchess, 2012). Indeed, these early romantic relationship experiences have been linked to enduring patterns repeatedly in research (Collins, 2003).

On average, rejection sensitivity declined from age 16 to 19 within this sample. Thus, for most adolescents, worries over rejection dissipated as they approached early adulthood. Further, the association between initial levels and change over time in rejection sensitivity was significant and negative. This indicates that adolescents who started with elevated levels of rejection sensitivity tended to decline more than the average adolescent. This is not a trivial point. Taken together with the findings discussed above about long-term predictions from initial levels of rejection sensitivity, it suggests that those initial levels of rejection sensitivity at age 16 have an enduring impact, even if an individual’s rejection sensitivity decreases over the next few years. Although initial adolescent worries over rejection might subside, the dysfunctional expectations and behaviors of the individual within romantic relationships may remain problematic well past adolescence.

Although the average adolescent trends towards a decrease in rejection sensitivity from mid-to-late adolescence, the current study suggests there is variation in this change. In particular, the findings indicate a negative association between the change in adolescent rejection sensitivity and the self-and partner-reports of relative power within early adult romantic relationships. This association points to a some individuals who increase in rejection sensitivity during late adolescence, and are subsequently more submissive in their early adult romantic relationships. Interestingly, this rise in submissiveness is the only outcome related to late adolescent increase in rejection sensitivity. The current study builds upon prior cross-sectional research that had indicated a subset of rejection sensitive individuals who engage in “self-silencing” behaviors within their adolescent relationships (Galliher & Bentley, 2010; Harper, Dickson, & Welsh, 2006). The results suggest that perhaps these individuals learn to cope with their increasing worries about rejection from romantic partners by giving in whenever discord arises. While this may be temporarily effective in re-establishing the status quo, this pattern is likely maladaptive over time as individuals will not be able to establish a healthy autonomy within their relationships. Future work may shed more light on these individuals. It is possible they enter into relationships later in adolescence or that they experience more frequent or more traumatic breakups. It is quite possible that this pattern is more common among individuals experiencing relationship violence, and that increasing patterns of rejection sensitivity in adolescence serves as a marker. The ability of researchers and clinicians to shed light on this previously understudied phenomenon is paramount.

Results from this study also point to the role of gender in this process. Mean differences at age 16 confirmed that males reported more elevated levels of rejection sensitivity than did females, presumably in some part due to the perceived pressure over initiation of romantic relationships (Collins, Welsh, & Furman, 2009). There was also evidence of gender differences in the sequelae of increases in rejection sensitivity during late adolescence. Among individuals who displayed relative increases in rejection sensitivity during the late adolescent years, females were more likely than males to adopt a submissive style in their future romantic relationships. This offers support for findings from cross-sectional studies that self-silencing is a coping mechanism that women are more likely to adapt in situations where they experience worry over rejection or negative evaluation (London, Downey, Romero-Canyas, Rattan, & Tyson, 2012; Seiffge-Krenke, 2011). The long-term consequences of this submissive coping strategy and whether it impedes healthy development merit further attention.

A critical area for researchers to better understand the developmental pattern of rejection sensitivity discussed in this study is in the turbulence of adolescent relationships. While beyond the scope of this investigation, the transition in and out of early romantic relationships during mid-to-late adolescence provides a unique opportunity to understand how and for whom rejection sensitivity changes. Given that adolescents may have very different relationship experiences in this period, it is quite likely that these relationships serve as mediators or moderators of the pattern of change in rejection sensitivity outlined here. The consistency of links between types of measurement (observations, self-report, partner-report) suggests the likelihood of common mechanisms. What is clear from these results is that development in late adolescence is crucial for understanding the nature and course of future romantic relationships.

There are several limitations to these findings that also warrant consideration. First, the lack of person centered analyses prevents making strong claims about specific profiles of adolescents over time, though the associations between change in rejection sensitivity and later submissiveness suggest some potential for exploring differing trajectories. Second, we examined isolated romantic relationships rather than the ways that specific relationships changed over time. This provides a useful snapshot of the potential impact of rejection sensitivity but does not get at the processes and patterns of influence and change within these relationships. Third, our sample was not as large as other studies and so power may have limited us for detecting certain associations. While we have confidence in those associations we detected, it may be that future work will capture additional connections. Finally, this study captures the development of rejection sensitivity starting at age 16, thus not capturing some formative years in which rejection sensitivity is likely developing. Past work suggests that family factors and early adolescent peer experiences shape the development of rejection sensitivity prior to age 16 (Collins, Welsh, & Furman, 2009; London et al., 2007), so the current findings may be thought of as capturing part of a longer-term process.

It is clear that worries over rejection in adolescence may translate into struggles in future romantic relationships. The current study suggests two illustrations by which this may occur. First, individuals who are sensitive to rejection at age 16 are less likely to have future romantic partners, are more anxious and avoidant in relationships, and have relationships that are marked by a more negative interaction style. Second, individuals who experience relative increases in their rejection sensitivity from age 16 to 19, particularly females, are more likely to be submissive in their future romantic relationships. Thus, intervention efforts that target reducing the anxiety and worry over being rejected by friends and romantic partners in adolescence may have lasting positive impacts in adulthood.

Acknowledgements

This study and its write-up were supported by grants from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and the National Institute of Mental Health (9R01 HD058305-11A1 & R01-MH58066).

Contributor Information

Christopher A. Hafen, University of Virginia, chris.hafen@virginia.edu, 350 Old Ivy Way, Charlottesville, VA 22903

Ann Spilker, University of Virginia, acs4a@virginia.edu.

Joanna Chango, University of Virginia, jmc4ja@virginia.edu.

Emily S. Marston, Salem VA Medical Center, egmarston@gmail.com

Joseph P. Allen, University of Virginia, allen@virginia.edu

References

- Bartholomew K. Avoidance of intimacy: An attachment persective. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1990;7:147–178. [Google Scholar]

- Brennan KA, Clark CL, Shaver PR. Self-report measurement of adult attachment. In: Simpson JA, Rholes WS, editors. Attachment theory and close relationships. New York: Guilford Press; 1998. pp. 46–76. [Google Scholar]

- Carver K, Joyner K, Udry JR. National estimates of adolescent romantic relationships. In: Florsheim P, editor. Adolescent romantic relations and sexual behavior: Theory, research and practical implications. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2003. pp. 23–56. [Google Scholar]

- Collins WA. More than myth: The developmental significance of romantic relationships during adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2003;13:1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Collins WA, Welsh DP, Furman W. Adolescent romantic relationships. Annual Review of Psychology. 2009;60:631–652. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, Dodge KA. A review and reformulation of social information-processing mechanisms in children’s social adjustment. Psychological Bulletin. 1994;115:74–101. [Google Scholar]

- Donnelan MB, Larsen-Rife D, Conger RD. Personality, family history, and competence in early adult romantic relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2005;88:562–576. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.88.3.562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downey G, Feldman SI. Implications of rejection sensitivity for intimate relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996;70:1327–1343. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.70.6.1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downey G, Freitas AL, Michaelis B, Khouri H. The self-fulfilling prophecy in close relationships: Rejection sensitivity and rejection by romantic partners. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;75:545–560. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.75.2.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downey G, Lebolt A, Rincón C, Freitas AL. Rejection sensitivity and children’s interpersonal difficulties. Child Development. 1998;69:1074–1091. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK. The performance of the full information maximum likelihood estimator in multiple regression models with missing data. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 2001;61:713–740. [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, Buhrmester D. Children’s perceptions of the personal relationships in their social networks. Developmental Psychology. 1985;21:1016–1024. [Google Scholar]

- Galliher RV, Bentley CG. Links between rejection sensitivity and adolescent romantic relationship functioning: The mediating role of problem-solving behaviors. Journal of Aggression. 2010;19:603–623. [Google Scholar]

- Grotevant HD, Cooper CR. Patterns of interaction in family relationships and the development of identity exploration in adolescence. Child Development. 1985;56:415–428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilron R, Gutchess AH. Remembering first impressions: Effects of intentionality and diagnosticity on subsequent memory. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience. 2012;12:85–98. doi: 10.3758/s13415-011-0074-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper MS, Dickson JW, Welsh DP. Self-silencing and rejection sensitivity in adolescent romantic relationships. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2006;35:435–443. [Google Scholar]

- Levy SR, Ayduk O, Downey G. The role of rejection sensitivity in people’s relationships with significant others and valued social groups. In: Leary MR, editor. Interpersonal rejection. New York: Oxford University Press; 2001. pp. 251–289. [Google Scholar]

- London B, Downey G, Bonica C, Paltin I. Social causes and consequences of rejection sensitivity. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2007;17:481–506. [Google Scholar]

- London B, Downey G, Romero-Canyas R, Rattan A, Tyson D. Gender-based rejection sensitivity and academic self-silencing in women. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2012;102:961–979. doi: 10.1037/a0026615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald G, Leary MR. Why does social exclusion hurt? The relationship between social and physical pain. Psychological Bulletin. 2005;131:202–223. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.131.2.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madsen SD, Collins WA. The salience of adolescent romantic experiences for romantic relationship qualities in young adulthood. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2011;21:789–801. [Google Scholar]

- Marston EG, Hare A, Allen JP. Rejection sensitivity in late adolescence: Social and emotional sequelae. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2010;20:959–982. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00675.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten CL, Telzer EH, Fuligni AJ, Lieberman MD, Eisenberger NI. Time spent with friends in adolescence relates to less neural sensitivity to later peer rejection. Social Cognitive & Affective Neuroscience. 2012;7:106–114. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsq098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathieson LC, Murray-Close D, Crick NR, Woods KE, Zimmer-Gembeck M, Geiger TC, Morales JR. Hostile intent attributions and relational aggression: The moderating roles of emotional sensitivity, gender, and victimization. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2011;39:977–987. doi: 10.1007/s10802-011-9515-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mischel W, Shoda Y. A cognitive-affective system theory of personality: Reconceptualizing situations, dispositions, dynamics, and invariance in personality structure. Psychological Review. 1995;102:246–268. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.102.2.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén BO, Muthén LK. Mplus (Version 6.12) [Computer software] Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén.; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Neyer FJ, Asendorpf JB. Personality-relationship transaction in young adulthood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2001;81:1190–1204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins RW, Caspi A, Moffitt TE. It’s not just who you’re with, it’s who you are: Personality and relationship experiences across multiple relationships. Journal of Personality. 2002;70:925–964. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.05028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero-Canyas R, Downey G, Berenson K, Ayduk O, Kang NJ. Rejection sensitivity and the rejection-hostility link in romantic relationships. Journal of Personality. 2010;78:119–148. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2009.00611.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose AJ, Rudolph KD. A review of sex differences in peer relationship processes: Potential trade-offs for the emotional and behavioral development of boys and girls. Psychological Bulletin. 2006;132:98–131. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.1.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seiffge-Krenke I. Coping with relationship stressors: A decade review. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2011;21:196–210. [Google Scholar]

- Smith JD, Welsh DP, Fite PJ. Adolescents’ relational schemas and their subjective understanding of romantic relationship interactions. Journal of Adolescence. 2010;33:147–157. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2009.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsh DP, Grello CM, Harper MS. When love hurts: Depression and adolescent romantic relationships. In: Florsheim P, editor. Adolescent romantic relations and sexual behavior: Theory, research and practical implications. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2003. pp. 185–211. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer-Gembeck MJ, Siebenbruner J, Collins WA. Diverse aspects of dating: Associations with psychosocial functioning from early to middle adolescence. Journal of Adolescence. 2001;24:313–336. doi: 10.1006/jado.2001.0410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]