Abstract

Background

We sought to apply modified labeling theory in a cross-sectional study of alcohol use disorder (AUD) to investigate the mechanisms through which perceived alcohol stigma (PAS) may lead to the persistence of AUD and risk of psychiatric disorder.

Methods

We conducted structural equation modeling (SEM) including moderated mediation analyses of two waves (W1 and W2) of data from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. We analyzed validated measures of PAS, perceived social support, social network involvement, and psychiatric disorders among (n = 3608) adults with two or more DSM-5 AUD symptoms in the first two of the three years between the W1 and W2 survey. Cross-sectional analyses were conducted owing to the assessment of PAS only at W2.

Results

Per mediation analyses, lower levels of perceived social support explained the association of PAS with past-year AUD and past-year internalizing psychiatric disorder at W2. The size of the mediated relationship was significantly larger for those classified as labeled (i.e., alcoholic) per their prior alcohol treatment or perceived need (n = 938) as compared to unlabeled (n = 2634), confirming a hypothesis of moderated mediation. Unexpectedly, mediation was also present for unlabeled individuals.

Conclusions

Lower levels of social support may be an important intermediate outcome of alcohol stigma. Longitudinal data are needed to establish the temporal precedence of PAS and its hypothesized intermediate and distal outcomes. Research is needed to evaluate direct measures of labeling that could replace proxy measures (e.g., prior treatment status) commonly employed in studies of the stigma of psychiatric disorders.

Keywords: Alcoholism stigma, Alcohol, Psychiatric disorders, Modified labeling theory, Social support, Social network

1. Introduction

Alcohol use disorders (AUDs) are perhaps one of the most stigmatized medical or psychiatric conditions (Schomerus et al., 2010). Over half of the general public attributes the cause of AUDs to one’s “own bad character” (Link et al., 1999) or believes that individuals are to blame for their illness (Crisp et al., 2000). Perceived stigma, which develops during socialization, is defined as individuals’ awareness of the discrimination and devaluation directed toward those with conditions that are viewed unfavorably (Link, 1987). For persons who acquire stigmatized conditions, perceived stigma becomes personally relevant, which may provoke fear of being rejected by others (Link, 1987). Among people affected by substance use disorders, perceived stigma is associated with a number of adverse outcomes that complicate recovery, including poorer mental health functioning (Smith et al., 2010), higher depression scores (Luoma et al., 2010), lower rates of treatment utilization (Keyes et al., 2010), lower quality of life (Luoma et al., 2007) and poorer physical health (Ahern et al., 2007). Scholars maintain that stigma is detrimental to achieving and sustaining recovery from addiction (Laudet, 2008; White, 2007, 2009).

Modified labeling theory (MLT) elucidates the mechanisms via which stigma leads to adverse consequences for those affected by psychiatric conditions (Link, 1987; Link et al., 1989). A major proposition of MLT is that the consequences of perceived stigma for people with psychiatric conditions are dependent on labeling, such that perceived stigma has personal relevance to those who carry a stigmatized label (e.g., alcoholic). Individuals may be labeled during various social exchanges, and in particular, MLT describes that labeling may occur if and when one receives treatment through the assignment of a formal diagnosis (Link, 1987).

According to MLT, to avoid further stigmatization, labeled individuals may employ specific coping orientations, such as maintaining secrecy about a psychiatric condition or avoiding potentially uncomfortable or threatening social interactions (Link et al., 1991). Secrecy and avoidance are thought to damage social ties and result in other negative outcomes despite their beneficial appearance (Link et al., 1991). Consistent with this notion, meta-analyses have identified a reliable association between perceived stigma and weakened social support or integration (Livingston and Boyd, 2010). Employing ineffective coping orientations has been linked to diminished self-esteem, self-efficacy, general well being, and job market participation and earnings (Link et al., 1987, 1989, 1997; Wahl, 1999; Wright et al., 2000), and is thought to ultimately increase individuals’ likelihood of relapse and exacerbation of psychiatric conditions (Link et al., 1989). While MLT focuses on social and individual level exchanges, we note that stigma can also result in discrimination at the institutional or structural level (Deacon, 2006; Link and Phelan, 2001; Williams et al., 2012).

While intervention research has begun to focus on preventing or ameliorating the outcomes of addiction stigma (Livingston et al., 2012), we are aware of few studies in the alcohol literature that have investigated mechanisms through which perceived alcohol stigma (PAS) may lead to adverse consequences. A recent study found a negative association between PAS and perceived social support among individuals with AUDs in the United States general population, which was stronger among individuals classified as labeled as compared to unlabeled (Glass et al., 2013). In contrast, Luoma et al. (2010) did not find an association between perceived substance use stigma (drug or alcohol stigma) and social support in an addictions treatment sample. However, their study did find a positive association between perceived stigma and self-concealment. Rather than focusing on coping strategies, others have analyzed the internalization of PAS. Schomerus et al.’s et al. (2011) analysis of an alcohol detoxification sample found positive correlations between PAS (which they deem “stereotype awareness”), self-stereotyping based on one’s AUD, and self-esteem decrement. In line with these findings, an association between perceived substance use stigma (i.e., alcohol or drug) and internalized stigma has been found in other addiction treatment samples (Luoma et al., 2007, 2010).

While these studies offer insight into intermediate outcomes, we are aware of no alcohol research formally investigating mediators of hypothesized stigma outcomes. While higher PAS has been linked to lower levels of social support (Glass et al., 2013), only alcohol research outside of the stigma literature has linked social network measures such as social support and related constructs to negative outcomes. For example, a smaller social network and lack of social relationships or social support is known to be a risk factor for increased alcohol consumption (Pressman et al., 2005) and depressive symptoms (Booth et al., 1992). Conversely, alcohol-abstinent social networks and treatment-supportive relationships predict alcohol dependence recovery (Hunter-Reel et al., 2010). To summarize, while stigma, social relationships, and outcomes have been linked in separate lines of alcohol research, formal tests of mediation are warranted to better understand the mechanisms of alcohol stigma that may worsen psychiatric outcomes.

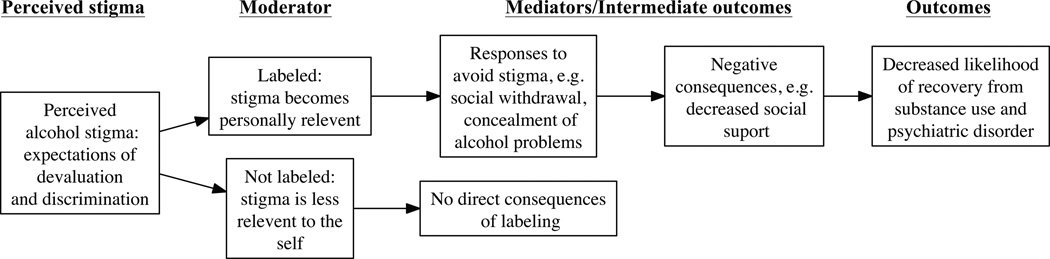

An ideal data source to test an application of MLT would provide population-based data on labeled and unlabeled persons with AUDs, and the requisite measures of PAS, social network variables, and psychiatric outcomes (see Fig. 1). Such data are available within the National Epidemiologic Survey of Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC), a representative survey of the United States general population. While NESARC provides longitudinal assessments, several key variables (e.g., PAS) were only assessed at the follow-up interview, which precluded our ability to establish temporal precedence. Hence, we conducted cross-sectional analyses of NESARC using structural equation modeling (SEM) to test two basic hypotheses of MLT: (1) the relationship of PAS with past-year AUD and past-year internalizing psychiatric disorders would be positive and mediated by individuals’ social network involvement and perceived social support, and (2) the mediated relationship would exist for labeled, but not unlabeled persons. While MLT assumes perceived stigma is inconsequential for unlabeled individuals, we deemed it worthwhile to evaluate this empirically for alcohol stigma.

Fig. 1.

A conceptual model of alcohol use disorder stigma based on modified labeling theory.

2. Methods

2.1. Study sample

We analyzed data from Wave 1 (W1) and Wave 2 (W2) of NESARC (Grant et al., 2007). The complex survey design permitted population-representative estimates of United States adults living in noninstitutionalized settings. In-person interviews for W1 were conducted with 43,093 respondents (81% of those targeted) during 2001–2002, with 34,653 reinterviewed in 2004–2005 (86.7% of W1 respondents). DSM-IV psychiatric disorders and related constructs were assessed with the Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-IV (AUDADIS-IV; Grant et al., 2003). The methodology and participants of NESARC have been described elsewhere (Grant et al., 2003, 2004, 2009). To include a broad range of psychopathology without needing diagnostic subgroup analyses (e.g., alcohol abuse versus dependence), we analyzed data from respondents who met two or more criteria of the diagnosis of Alcohol Use Disorder in the DSM-5, the recently approved revision of the DSM nomenclature (Agrawal et al., 2011; Hasin et al., 2013) at any point in the first two of the three years between the W1 and W2 interviews (n = 3608). Hence, the sample criteria were consistent with the approved DSM-5 nomenclature with the exception that 2+ AUD symptoms could have occurred over a two-year (as opposed to a one-year) period.

2.2. Variables

2.2.1. Outcome variables

We created two dichotomous variables from the W2 data indicating whether or not respondents met criteria for past-year DSM-5 AUD or past-year DSM-IV internalizing disorder (mood or anxiety disorders including major depression, bipolar I and II, dysthymia, social phobia, specific phobia, generalized anxiety disorder, and post-traumatic stress disorder). The individual psychiatric disorders have test-retest reliabilities (kappa) that range from 0.40 to 0.77 (Grant et al., 2003; Ruan et al., 2008). We note that being positive for past-year AUD was an indicator of AUD persistence (versus AUD remittance) owing to the use of alcohol-affected status in the prior two years to define the analytic sample. In contrast, being positive for past-year internalizing disorder could indicate incident disorder or persistent disorder (versus remittance or remaining unaffected).

2.2.2. Mediators: social network involvement (SNI) and perceived interpersonal social support (ISS)

At W2 only, the Social Network Index (Cohen et al., 1997) was collected. This measure assessed recent involvement in 11 types of social relationships (e.g., relatives, friends, co-workers, neighbors) (intraclass correlation coefficient [ICC] = 0.70; Ruan et al., 2008). Our variable for SNI summed the types of social relationships that were active in the past two weeks (Cohen et al., 1997). In the W2 assessment only, the 12-item version of the interpersonal support evaluation list (ISEL-12) to measure ISS (α = 0.82) was collected (Cohen et al., 1985; Ruan et al., 2008), which has been extensively used in studies involving alcohol, health, and mental health populations (King, 2012; Moak and Agrawal, 2010; Swartz, 2005). The ISEL-12 evaluates respondents’ current perceived availability of interpersonal resources and includes three subscales of interpersonal belonging, appraisal, and perceptions of tangible interpersonal resources (e.g., “If I were sick, I know I would find someone to help me with my daily chores.”). ISS was modeled as a latent variable.

2.2.3. Moderator: labeled status

Following prior research (Glass et al., 2013), we inferred labeling status (0 = unlabeled, 1 = labeled) through the receipt of alcohol treatment or having a perceived unmet need for alcohol treatment based on assessments at W1 and W2. Perceived unmet need for treatment was assessed with the question, “Was there ever a time when you thought that you should see a doctor, counselor, or other health professional or seek any other help for your drinking, but you didn’t go?” In research on the stigma of serious mental illness, labeled status has been inferred through the receipt of treatment, under the assumption that receipt of a psychiatric diagnosis results in social labeling. In order to fully capture labeled status, we also included perceived unmet need for treatment in our definition to recognize that labeled status may exist on a continuum that includes self-labeling (Moses, 2009; Thoits, 1985) and very few individuals with AUDs receive treatment (Cohen et al., 2007).

2.2.4. Perceived alcohol stigma

At W2, the 12-item Perceived Devaluation- Discrimination (PDD) scale (Link, 1987) adapted for measuring PAS (α = 0.82; Ruan et al., 2008) was collected (e.g., “Most employers will hire a former alcoholic if he or she is qualified for the job”). (See Supplementary Material S1 for PDD items.1) We reversed the coding of six items so higher scores indicated more perceived stigma. Following prior work (Glass et al., 2013), we modeled PAS as a latent variable with adjustment for method effects due to reverse-item wording. Method effects adjustment was conducted with a correlated uniqueness approach, where the error terms of reverse-worded items were correlated (Marsh et al., 2010).

2.2.5. Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics

Sociodemographic variables were taken from W2 assessments. Categorical variables were chosen to be comparable with prior NESARC stigma studies (Keyes et al., 2010; Smith et al., 2010). The NESARC data combine race/ethnicity in five groupings: White; Black; Native American or Alaskan Native; Asian, Hawaiian, or Pacific Islander; and Hispanic or Latino. Categorical variables also included education (less than high school, high school or GED equivalent, and greater than high school), gender, and marital status (never married, previously married, and currently married/living with someone as if married). Following Keyes et al. (2010), we created two variables representing social distance/proximity to persons with alcohol problems, which were coded as positive for those reporting (1) alcohol problems in any first-degree relative or (2) any live-in relationship with a partner with alcohol problems. To maintain additional degrees of freedom, age and family income remained quasi-continuous, and family income was log-transformed owing to its positive skew. To control for prior psychiatric disorders, we created a prior internalizing disorder variable (priorto- past-year, including lifetime at W1) and a prior AUD variable (lifetime DSM-IV AUD at W1). For descriptive purposes, we also created a variable to indicate internalizing disorder status including persistent (prior-to-past-year [lifetime W1 and prior-to-past year at W2] and past-year disorder [W2]), remitted (prior-to-past year but not past-year disorder), incident (past-year disorder only), and unaffected (no lifetime disorder [no disorder at W1 or W2]). We also controlled for lifetime DSMIV drug use disorder (DUD), including sedative, tranquilizer, opioid, amphetamine, cannabis, hallucinogen, cocaine, inhalant, heroin, and other drug use disorder. Last, we derived a prior-to-past-year alcohol problem severity measure by summing all DSM-IV abuse and dependence criteria (max score of 11) using W1 and W2 data. We omitted the alcohol craving criterion of DSM-5 AUD from this measure because it was not assessed at W1. The AUDADIS-IV assessed DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence symptoms with ICCs of 0.86 and 0.89, respectively (Grant et al., 2003).

2.3. Statistical analyses

We used STATA 12.0 (StataCorp, 2012) to calculate descriptive statistics and Mplus 7.0 (Muthén and Muthén, 1998) to conduct confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and structural equation modeling (SEM). CFA and SEM mediation models were computed within a multiple-group SEM framework to stratify the analyses by labeled status. For brevity, statistical estimation (e.g., survey design adjustment, categorical data estimator) and model evaluation procedures are described in Supplementary Material S2.1

2.3.1. Hypothesis 1

For hypothesis 1, we assessed mediation with the total indirect effect (product of coefficients) approach (MacKinnon, 2000) and computed 95% Monte Carlo confidence intervals to test the indirect effects (Mackinnon et al., 2004; Preacher and Selig, 2012). Conceptually, a total indirect effect represents the amount of the association between two variables that is explained by mediating variables. In multiple-mediator analysis, the total indirect effect is the sum of the specific indirect effects involving each mediator. SEM allowed for the simultaneous computation of all indirect effects for this study (i.e., for the multiple mediators, outcomes, and groups) with a single statistical model.

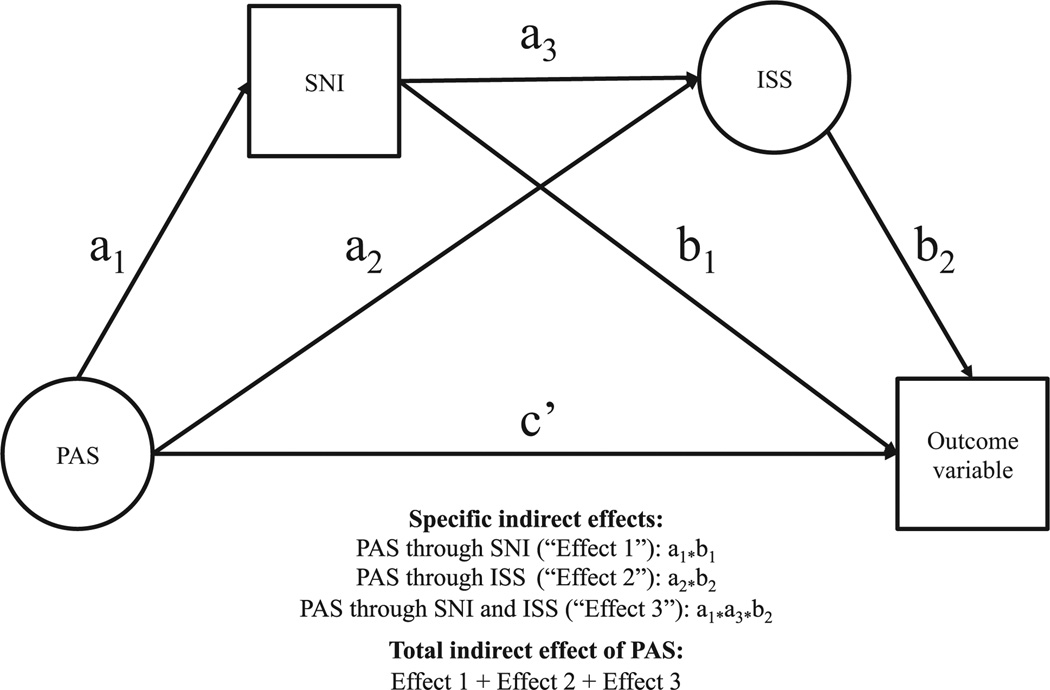

As shown in Fig. 2, we regressed outcomes on each mediator (ISS and SNI) and PAS. Regressions were specified in a way consistent with MLT such that SNI was the first mediator and ISS was the second mediator. ISS was regressed on SNI and both mediators were regressed on PAS (MacKinnon, 2000). This was strictly a theory-based specification; we could not establish temporal ordering owing to the single cross-sectional assessment of PAS, SNI, and ISS at W2, which were concurrently assessed with the past-year psychiatric outcomes.

Fig. 2.

Path diagram displaying coefficients used to calculate the total indirect effects. Mediator-specific indirect effects are calculated by taking the product of the regression coefficients that represent the paths directed to and from the mediators. The total indirect effect is calculated by summing the mediator-specific indirect effects for each group. The paths involving the outcome variables (c’, b1 and b2) were computed separately for each outcome (e.g., b1 ALCOHOL USE DISORDER, b1 INTERNALIZING DISORDER) and for each group. The paths a1, a2, and a3 do not involve the outcome variables, thus required a single calculation for each group. PAS = perceived alcohol stigma, SNI = social network involvement, ISS = perceived interpersonal social support.

To measure effect size, we calculated mediation ratios for the mediator-specific indirect effects and the total indirect effects. Mediation ratios are one of the most common measures of effect size for mediation (MacKinnon, 2008). Here they represented the ratio of the indirect effect of PAS to the total effect of PAS for each outcome (MacKinnon, 2008).

2.3.2. Hypothesis 2

The multiple-group approach permitted examination of between-group differences in the strength of mediation by testing differences in the total indirect effect for each outcome. This is considered a test of a conditional indirect effect (i.e., “moderated mediation”) where the strength of a pathway is conditional upon a moderating variable (Preacher et al., 2007).

2.3.3. Statistical controls

The outcomes (past-year AUD and internalizing disorder) and all variables involved in the mediation analyses (PAS, SNI, and ISS) were regressed on all variables described in Section 2.2.5. Supplementary Material S31 depicts a path diagram for these statistical controls.

3. Results

Sample characteristics are displayed in Table 1. Respondents were mostly male, white, currently married, and had greater than a high school education. Approximately 72% met criteria for past-year AUD (hence, their AUD was persistent) and the remaining 28% were AUD-remitted. In the sample, 50% had a prior-to-past-year internalizing disorder (i.e., they met criteria for a lifetime W1 diagnosis and/or a prior-to-past year W2 diagnosis) and 33% had past-year internalizing disorder at W2 (which were not mutually exclusive). About 31% of the sample had persistent internalizing disorder (prior-to-past-year and past-year internalizing disorder), 20% had prior-to-past year disorder that was remitted, 2.6% had incident disorder, and 47% did not have internalizing disorder in their lifetime (not shown). The prevalence of past-year psychiatric disorder and prior psychiatric disorders was significantly higher for those labeled as alcoholic (per their prior treatment or perceived need) than unlabeled. Those in the labeled group had lower family incomes, less education, lower levels of perceived social support and social involvement, and were more likely to have a first-degree relative or a live-in partner with alcohol problems. Age, gender, racial/ethnic group status, and levels of PAS were not significantly different across groups. Supplementary Material S41 provides a partial correlation matrix for the endogenous variables of the SEM model. We note that compared to our analytic sample, those who were not in the analytic sample had significantly lower rates of past-year AUD (72.3% vs. 2.6%, respectively) and past-year internalizing disorders (33% vs. 19%), but similar levels of ISS (M = 42.6 vs. M = 42.5) and PAS (M = 37.4 vs. M = 37.9, respectively) (data not shown).

Table 1.

Characteristics of wave 2 NESARC respondents in the analytic sample.

| Variable | Weighted % (SE) or M (SE) | F (df) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (n = 3608) | Unlabeled (n = 2634) | Labeled (n = 938) | ||

| Age (continuous) | 37.9 (0.27) | 37.3 (0.31) | 39.6 (0.47) | 2.5 (1) |

| Gender | 1.3 (1) | |||

| Male | 68.3 (0.94) | 66.7 (1.07) | 72.9 (1.64) | |

| Female | 31.7 (0.94) | 33.4 (1.07) | 27.1 (1.64) | |

| Marital status | 6.8 (2)* | |||

| Presently married | 49.8 (1.04) | 50.2 (1.27) | 48.3 (1.95) | |

| Previously married | 16.5 (0.70) | 14.1 (0.72) | 23.5 (1.67) | |

| Never married | 33.7 (1.05) | 35.7 (1.31) | 38.2 (1.67) | |

| Family incomea (quasi-continuous, thousands) | 59.4 (1.16) | 62.0 (1.32) | 52.2 (1.79) | 19.1 (1)* |

| Race/ethnicity | 0.6 (3) | |||

| Hispanic | 11.8 (1.37) | 11.7 (1.34) | 11.6 (2.03) | |

| Black | 11.2 (0.85) | 11.8 (0.97) | 9.4 (1.07) | |

| Native American | 2.6 (0.39) | 2.1 (0.39) | 4.1 (0.85) | |

| Asian | 2.8 (0.65) | 3.3 (0.83) | 1.7 (0.62) | |

| White | 71.6 (1.65) | 71.2 (1.77) | 73.3 (2.16) | |

| Education | 9.1 (2)* | |||

| <HS | 12.3 (0.75) | 11.0 (0.79) | 15.8 (1.61) | |

| HS or GED | 27.1 (1.02) | 26.4 (1.24) | 29.7 (1.83) | |

| >HS | 60.5 (1.17) | 62.6 (1.31) | 54.6 (2.14) | |

| Live-in life partner with alcohol problems | 19.5 (0.85) | 13.8 (0.82) | 36.1 (2.01) | 77.2 (1)* |

| First-degree relative with alcohol problems | 45.3 (1.20) | 39.0 (1.25) | 64.6 (1.95) | 39.7 (1)* |

| Lifetime drug use disorder | 34.0 (1.18) | 27.7 (1.13) | 52.9 (2.07) | 49.4 (1)* |

| Social network involvement (mean) | 4.8 (0.04) | 4.9 (0.04) | 4.6 (0.07) | 12.0 (1)* |

| Perceived interpersonal social support (mean) | 42.5 (0.11) | 42.9 (0.12) | 41.4 (0.22) | 35.2 (1)* |

| Perceived alcohol stigma (PAS) (mean) | 37.4 (0.17) | 37.5 (0.18) | 37.2 (0.39) | 3.3 (1) |

| Prior-to-past-year AUD severity (mean) | 5.3 (0.06) | 4.4 (0.05) | 7.7 (0.10) | 323.0 (1)* |

| Prior AUD (W1 lifetime) | 64.5 (1.27) | 57.0 (1.34) | 86.6 (1.44) | 27.4 (1)* |

| Prior internalizing disorder (W1 lifetime and/or prior-to-past-year) | 50.2 (1.00) | 44.7 (1.16) | 66.3 (1.74) | 61.4 (1)* |

| Main outcomes | ||||

| Past-year AUD | 72.4 (0.97) | 70.7 (1.09) | 77.1 (1.80) | 23.5 (1)* |

| Past-year internalizing disorder | 33.2 (0.93) | 28.7 (1.03) | 46.3 (2.08) | 82.8 (1)* |

AUD = alcohol use disorder. Design-based F-test statistics are displayed with numerator degrees of freedom (ndf). Statistically significant (p < 0.05) F-tests are bolded and designated with an asterisk. Summed scales are reported for PAS and ISS. For this table only, missing data for PAS were addressed with mean replacement.

Family income is displayed as a raw value but was log transformed in the analyses. n = 36 individuals were excluded from further analyses owing to missing data on prior alcohol treatment). Internalizing disorders included major depression, bipolar I and II, dysthymia, social phobia, specific phobia, generalized anxiety disorder, and post-traumatic stress disorder

3.1. Model fit and estimates for CFA and SEM models

Multiple-group CFA models for the latent factors of PAS and ISS evidenced good fit and all factor loadings were statistically significant. Standardized loadings ranged from 0.263 to 0.701 for PAS items and 0.687 to 0.754 for ISS items. Item-specific factor loadings, measurement invariance analyses, and statistical significance of the models are reported in Supplementary Material S5.1

The multiple-group SEM had close to good fit to the data, χ2(715) = 1188, CFI = 0.966, TLI = 0.957, RMSEA = 0.019 (90% CI = 0.017–0.021). Table 2 contains covariate-adjusted path coefficients for the SEM model. As noted by MacKinnon (2008), the relation between the independent variable and mediator, as well as the relation between the mediator and outcome, together are the necessary relationships (and sufficient if their product is statistically significant) in mediation analysis. There was a statistically significant and negative association between PAS and the mediator ISS, which was the first necessary condition to establish mediation through ISS, in both labeled and labeled individuals. In addition, ISS was significantly associated with both past-year AUD and past-year internalizing disorder, which was the second necessary condition to establish mediation through ISS, for both labeled and unlabeled individuals. In contrast, the associations between PAS and SNI were not statistically significant, which precluded mediation through SNI in both labeled and unlabeled individuals. The association between SNI and past-year AUD was statistically significant in unlabeled individuals only, and SNI was not associated with past-year internalizing disorder.

Table 2.

Parameter estimates for the multiple-group mediation model.

| Path | Coefficienta | Labeled (n = 938) | Labeled (n = 938) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Std | Unstd | SE | p | Std | Unstd | SE | p | ||

| Direct effect: PAS to outcomes | |||||||||

| PAS → Past-year AUD | c’AUD | −0.104 | −0.136 | 0.094 | 0.151 | −0.043 | −0.065 | 0.056 | 0.242 |

| PAS → Past-year INT | c’INT | 0.040 | 0.071 | 0.087 | 0.415 | 0.003 | 0.006 | 0.062 | 0.919 |

| Mediational path: PAS to mediators | |||||||||

| PAS → SNI | a1 | −0.049 | −0.106 | 0.083 | 0.204 | −0.002 | −0.005 | 0.060 | 0.937 |

| PAS → ISS | a2 | −0.241 | −0.571 | 0.099 | 0.000 | −0.147 | −0.350 | 0.058 | 0.000 |

| Mediational path: SNI to ISS | |||||||||

| SNI → ISS | a3 | 0.250 | 0.274 | 0.045 | 0.000 | 0.206 | 0.210 | 0.024 | 0.000 |

| Mediational path: Mediators to outcomes | |||||||||

| SNI → Past-year AUD | b1 AUD | 0.008 | 0.005 | 0.031 | 0.874 | 0.074 | 0.048 | 0.021 | 0.020 |

| SNI → Past-year INT | b1 INT | −0.057 | −0.047 | 0.035 | 0.180 | −0.005 | −0.005 | 0.022 | 0.833 |

| ISS → Past-year AUD | b2 AUD | −0.283 | −0.156 | 0.038 | 0.000 | −0.126 | −0.080 | 0.023 | 0.001 |

| ISS → Past-year INT | b2 INT | −0.179 | −0.135 | 0.035 | 0.000 | −0.093 | −0.079 | 0.028 | 0.005 |

The coefficient column corresponds to the symbols of Fig. 2. Standard errors (SE) and p values are displayed for the unstandardized coefficients. Bolded values are statistically significant p < 0.05.

Std = standardized with respect to X and Y, Unstd = unstandardized, SNI = social network involvement, ISS = perceived interpersonal social support, PAS = perceived alcohol stigma, AUD = alcohol use disorder. Internalizing disorders (INT) included major depression, bipolar I and II, dysthymia, social phobia, specific phobia, generalized anxiety disorder, and post-traumatic stress disorder.

Although not central to our hypotheses, we note several other analysis results (results available from first author by request). The outcomes of past-year AUD and internalizing disorder, which were allowed to correlate in this model, were not significantly associated (r = 0.007 and r = −0.010 in the unlabeled and labeled groups, respectively). In addition, for descriptive purposes we conducted a supplemental regression of PAS on the internalizing disorder status variable. Those with persistent internalizing disorder had significantly higher PAS than those who were unaffected (standardized B = 0.192, p = 0.001), but differences in PAS with the remitted and incident groups were not statistically significant. Last, we compared the fit of our hypothesized model against a model where past-year AUD and internalizing disorder were independent variables, SNI and ISS were mediators, and PAS was the dependent variable. Our theorized model had a significantly better fit to the data than this alternative model, χ2(4) = 118.2, p < 0.0001.

3.2. Hypothesis 1

Statistically significant total indirect effects indicated that the relationships between PAS and the outcome variables, W2 AUD and W2 internalizing disorder, were mediated. Table 3 decomposes the indirect effects for each outcome and by labeled status. Consistently, for both outcomes and for both labeled and unlabeled individuals, the total indirect effects were positive, indicating that higher PAS was associated with an increased likelihood of psychiatric disorder through the overall mediated pathway. Mediator-specific indirect effects provided evidence for mediation through ISS, but not through SNI alone or through the combination of SNI and ISS.

Table 3.

Effects decomposition for the relationship between perceived alcohol stigma (PAS) and psychiatric outcomes. Mediation ratios are displayed to represent effect sizes.

| Labeled (n = 938) | Unlabeled (n = 2634) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Std | Unstd | SE or 95% CI | Mediation ratio (%) | Std | Unstd | SE or 95% CI | Mediation ratio (%) | |

| W2 past-year alcohol use disorder (AUD) | ||||||||

| Indirect effect | ||||||||

| PAS ⇒ SNI ⇒ AUD | 0.000 | −0.001 | −0.010 to 0.008 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 | −0.007 to 0.006 | 0 |

| PAS ⇒ ISS ⇒ AUD | 0.068 | 0.089 | 0.042 to 0.147 | 39 | 0.019 | 0.028 | 0.011 to 0.048 | 30 |

| PAS ⇒ SNI ⇒ ISS ⇒ AUD | 0.003 | 0.005 | −0.002 to 0.012 | 2 | 0.000 | 0.000 | −0.002 to 0.002 | 0 |

| Total indirect effect | 0.071 | 0.093 | 0.046 to 0.147 | 41 | 0.018 | 0.028 | 0.010 to 0.050 | 30 |

| Total effecta | 0.175 | 0.229 | 0.104 | – | 0.061 | 0.093 | 0.059 | – |

| Past-year internalizing disorder (INT) | ||||||||

| Indirect effects | ||||||||

| PAS ⇒ SNI ⇒ INT | 0.003 | 0.005 | −0.004 to 0.020 | 3 | 0.000 | 0.000 | −0.003 to 0.003 | 0 |

| PAS ⇒ ISS ⇒ INT | 0.043 | 0.077 | 0.035 to 0.129 | 49 | 0.014 | 0.028 | 0.008 to 0.051 | 82 |

| PAS ⇒ SNI ⇒ ISS ⇒ INT | 0.002 | 0.005 | 0.002 to 0.011 | 3 | 0.000 | 0.000 | −0.002 to 0.003 | 0 |

| Total indirect effect | 0.048 | 0.086 | 0.040 to 0.141 | 55 | 0.014 | 0.028 | 0.007 to 0.052 | 82 |

| Total effecta | 0.088 | 0.157 | 0.076 | – | 0.017 | 0.034 | 0.058 | – |

The total effect is calculated as the sum of the total indirect effect and the indirect effect. Absolute values are used to calculate the total effect for the mediation ratio when indirect and direct effects have opposite signs (MacKinnon, 2008). Bolded rows indicate a statistically significant association.

Std = standardized with respect to X and Y, Unstd = unstandardized, SNI = social network involvement, ISS = perceived interpersonal social support. Internalizing disorders included major depression, bipolar I and II, dysthymia, social phobia, specific phobia, generalized anxiety disorder, and post-traumatic stress disorder.

With regard to the effect sizes for the statistically significant mediated relationships, ISS mediated approximately 41% and 30% of the total relationship between PAS and past-year AUD for labeled and unlabeled individuals, respectively. Preacher and Kelley (2011) note that these ratios should be interpreted within the context of the size of the total effects. That is, larger mediation ratios are more “interesting” when accompanied by larger, as compared to smaller, total effects. For example, for past-year internalizing disorder the mediation ratio for ISS was larger for unlabeled individuals (82%) than labeled individuals (55%), yet the total effect for unlabeled individuals was quite small.

3.3. Hypothesis 2

The total indirect effect was significantly larger in labeled than in unlabeled individuals for both outcomes, providing evidence for moderated mediation. The size of the unstandardized difference in the total indirect effect between labeled and unlabeled individuals for the outcome past-year AUD was 0.065 (95% CI 0.012–0.114) and for past-year internalizing disorder 0.058 (95% CI 0.006–0.117). Standardized values for these coefficients were 0.053 and 0.034, respectively.

3.4. Robustness checks

Six items in the PDD inquire about expectations of discrimination or devaluation in relation to a person’s prior treatment status (see Supplementary Material 11). This warranted sensitivity analysis of a latent PAS factor excluding these items owing to the use of prior treatment status as a proxy for labeling. When excluding the treatment-specific PDD items, the fit remained good (CFI = 0.970, TLI = 0.955, RMSEA = 0.018 [90% CI = 0.015–0.020]) and results were consistent with regard to the direction and statistical significance of the indirect effects and their between-group difference (not shown).

4. Discussion

By employing a theory-driven test of the mechanisms of stigma and a consideration of labeling status, the current study extends findings from prior research that established correlations between perceived or internalized substance use stigma and psychiatric outcomes, but did not test mediated pathways. To our knowledge, this is the first empirical study to evaluate major propositions of modified labeling theory as applied to AUDs.

While perceived stigma and social support were only assessed at the follow-up interview, higher PAS was associated, by way of mediation through lower levels of perceived social support, with the persistence of AUD and an increased risk internalizing psychiatric disorder over the follow-up period of NESARC. Based on mediation ratios, a substantial portion of the relationships between PAS and psychiatric outcomes were mediated by perceived social support. The finding of mediation is in line with a prior study on depression stigma, which demonstrated that reduced social support mediated the relationship between perceived stigma and quality of life (Chung et al., 2009). Lower levels of social support may be an important mechanism via which the perceived stigma of AUDs is associated with psychiatric outcomes. With cross-sectional data, we were unable to determine if these associations may be causal in nature. We cannot rule out reverse causality, and it is also possible that bi-directional relationships exist between these variables. For example, AUD persistence and/or internalizing disorder may reduce social support, lead people to perceive more stigma, and/or heighten sensitivity to the potential effects of stigma. Scant research in the broader stigma literature exists that has utilized prospective designs, which is a significant methodological limitation of this literature (Hatzenbuehler, 2009; Livingston and Boyd, 2010).

It was unexpected that we found no direct relationship between PAS and social network involvement, as well as no mediation through this variable. In a prior NESARC study, the relationship between PAS and SNI was weak but significantly associated (Glass et al., 2013). Nonetheless, we chose to analyze a measure of SNI in the current study because we sought to conduct a comprehensive test of MLT, which posits that treatment receipt results in social labeling and a subsequent reduction and/or weakening of social ties owing to stigma (Link et al., 1989). In the current analysis, the specification of a path between the social network and perceived social support variables (which was necessary to test the mediation model) attenuated the association between PAS and SNI. It is possible that one’s perceptions of their social support may be more important than the simple presence of interactions with others. More specifically, the SNI measure does not assess the quality of social relationships. Additionally, we note that the ISS and SNI measures do not tap into aspects of relationships that may be particularly important with AUD populations. In treatment, and particularly with Alcoholics Anonymous, people with AUDs may be encouraged to rebuild estranged family relationships and seek support networks consisting of others in recovery. Active heavy drinkers, on the other hand, may intentionally seek alcohol-focused friendships (Leonard et al., 2000) to provide drinking partners, escape from interpersonal concerns related to social stigma (e.g., judgment), and acceptance of addictive behaviors that may be typically hidden from others. Such friendships may increase the diversity of one’s social network notwithstanding stigma, yet may not provide the benefits of non-alcohol-focused friendships. These complex relationships, including the pro-drinking nature of one’s social network, were not assessed in NESARC.

Our investigation of moderation by labeling status yielded interesting findings. The significantly larger mediated relationship for those classified as labeled compared to unlabeled supports the general proposition of modified labeling theory that the negative outcomes of stigma are dependent on the labeling process (Link et al., 1989). The results are consistent with studies on non-substance-related psychiatric illness stigma that conducted stratified analyses or formal tests of moderation and found an interaction between stigma and labeling status, with previously treated individuals having poorer outcomes (Kroska and Harkness, 2006; Link et al., 1989, 1991, 1997). We caution that this finding should not be interpreted such that treatment should be avoided. Rather, decreasing stigma would be considered the appropriate target for intervention, which might include targeting the reduction of stigma among the general population and treatment providers (Livingston et al., 2012; McLaughlin and Long, 1996).

Early writings on modified labeling theory described that perceived stigma only has negative consequences for individuals who carry the associated stigmatized label, such as those who have been mental health patients (Link et al., 1989). However, our analyses suggested that PAS might have consequences for untreated persons. Specifically, we found that even among individuals who were deemed to be unlabeled, a positive association existed between PAS and psychiatric outcomes that was mediated through lower levels of social support. Research supports that the general public uses information about others’ former treatment status as cues for labeling, judgment, and social distancing (Ben-Porath, 2002; Crisp et al., 2000; Link and Cullen, 1983), and research conducted with individuals who have non-substance-related psychiatric disorders (e.g., depression, serious mental illness) supports the use of prior treatment status as a proxy for labeling (Kroska and Harkness, 2006; Link, 1987; Link et al., 1989). However, it is plausible that social labeling by means other than treatment status exists to a greater extent for the addictive disorders, given the externalizing nature of the symptoms (Hasin and Kilcoyne, 2012), low rates of treatment utilization (Cohen et al., 2007; Glass et al., 2010), and the inherent denial that is believed to exist regarding one’s own problems (Dare and Derigne, 2010; Edlund et al., 2006; Grant, 1997).

We believe this raises an important question: how should labeling status be inferred in research on alcohol and drug stigma? While proxy measures for labeling status such as previous treatment participation and/or time since an individual’s initial diagnosis have been used (Link et al., 1989; Mueller et al., 2006), they may have limitations. A dissonance between one’s own behavior and societal conceptions of what is normal may result in “self-labeling,” which may occur independently of treatment and provoke a fear of stigma (Moses, 2009; Thoits, 1985). Even those who undergo treatment may not personalize their assigned psychiatric diagnosis (Moses, 2009) and/or may become empowered to reject the social connotations associated with psychiatric labels (Camp et al., 2002; Howard, 2008). It has also been argued that certain types of treatment or specific treatment programs may encourage diagnostic labels more than others (Rosenfield, 1997), which may be applicable to alcohol treatment services. To replace proxy measures, we suggest development of direct assessments of labeling via the query of individuals’ perception of being labeled, the extent to which their addiction has been disclosed to others (Bos et al., 2009), or the experience of being referred to with a stigmatized label or diagnosis (e.g., drunk or alcoholic). Direct assessment of labeling would permit study of its impact on treatment utilization, which is not possible when treatment is used as a proxy for labeling.

4.1. Limitations

The analyses lacked causal ordering for PAS, the mediators, and outcomes. Without longitudinal data, reverse causality is an alternative explanation for the mediated pathway, so that we cannot rule out that low levels of social support lead to increased PAS, and both are associated with AUD and internalizing disorders. However, longitudinal studies of non-substance-related psychiatric stigma have not revealed a consistent direction in the stigma-social support relationship (Mueller et al., 2006; Perlick, 2001; Roeloffs et al., 2003). Our study may have also been limited by the use of a general measure of SNI, which does not make distinctions between out-ofhome and in-home social involvement (Link et al., 1989; Perlick, 2001), does not probe whether absence of social interaction was due to stigma, does not determine whether individuals avoided contact with their social network or vice versa, and importantly does not characterize support in terms of its alcohol-positive or - negative nature. In addition, it is possible that variables related to stigma, social support, and AUD were excluded from the analysis, which could result in bias. Finally, PAS and social support are both cognitive constructs, whereas SNI is a behavioral measure; it may be that a behavioral measure (e.g., experienced stigma) would be associated with SNI.

4.2. Conclusions

This cross-sectional study provided support for the relevance of two major propositions of MLT to the study of AUDs. Lower levels of social support may be an important intermediate outcome of alcohol stigma, which should be evaluated, along with the specific coping orientations described by MLT, as intermediate outcomes. Importantly, longitudinal research is needed to establish the temporal precedence of PAS and its hypothesized intermediate and distal outcomes. While we also found support for labeling as a moderator of the relationship between perceived stigma and negative outcomes, research is needed to establish direct measures of labeling that could replace proxy measures commonly employed in studies of the stigma of psychiatric disorders.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

We are grateful to Kristopher J. Preacher at Vanderbilt University for providing statistical consultation for the statistical analysis.

Role of funding source

This project received support from the National Institutes of Health under Ruth L. Kirschtein National Research Service Awards 5T32 DA015035 (JEG), 1F31AA021034 (JEG), T32 AA007477-21 (OPM). SDK received funding from ABMRF/The Foundation for Alcohol Research. The funding sources had no further role in this study.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.08.016.

Footnotes

Supplementary material for this article can be found by accessing the online version of this paper. Please see Appendix A for more information.

Contributors

JEG conceptualized the study’s design, conducted statistical analyses, and prepared drafts of the manuscript. OPM assisted with background literature and edited drafts of the manuscript. SDK provided methodological consultation and edited drafts of the manuscript. BGL provided consultation on the theoretical framework and edited drafts of the manuscript. KKB edited drafts of the manuscript and helped with the design of the study.

Conflict of interest

No conflict declared.

References

- Agrawal A, Heath AC, Lynskey MT. DSM-IV to DSM-5: the impact of proposed revisions on diagnosis of alcohol use disorders. Addiction. 2011;106:1935–1943. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03517.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahern J, Stuber J, Galea S. Stigma, discrimination and the health of illicit drug users. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;88:188–196. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Porath DD. Stigmatization of individuals who receive psychotherapy: an interaction between help-seeking behavior and the presence of depression. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2002;21:400–413. [Google Scholar]

- Booth BM, Russell DW, Yates WR, Laughlin PR, Brown K, Reed D. Social support and depression in men during alcoholism treatment. J. Subst. Abuse. 1992;4:57–67. doi: 10.1016/0899-3289(92)90028-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bos AER, Kanner D, Muris P, Janssen B, Mayer B. Mental illness stigma and disclosure: consequences of coming out of the closet. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2009;30:509–513. doi: 10.1080/01612840802601382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camp DL, Finlay WM, Lyons E. Is low self-esteem an inevitable consequence of stigma? An example from women with chronic mental health problems. Soc. Sci. Med. 2002;55:823–834. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00205-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung L, Pan A-W, Hsiung P-C. Quality of life for patients with major depression in Taiwan: a model-based study of predictive factors. Psychiatry Res. 2009;168:153–162. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2008.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen E, Feinn R, Arias A, Kranzler HR. Alcohol treatment utilization: findings from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;86:214–221. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Doyle WJ, Skoner DP, Rabin BS, Gwaltney JM. Social ties and susceptibility to the common cold. JAMA. 1997;277:1940–1944. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Mermelstein R, Karmarck T, Hoberman HM. Measuring the functional components of social support. In: Sarason IG, Sarason BR, editors. Social Support: Theory, Research, and Applications. Newberry: Sage; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Crisp AH, Gelder MG, Rix S, Meltzer HI, Rowlands OJ. Stigmatisation of people with mental illnesses. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2000;177:4–7. doi: 10.1192/bjp.177.1.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dare PAS, Derigne L. Denial in alcohol and other drug use disorders: a critique of theory. Addict. Res. Theory. 2010;18:181–193. [Google Scholar]

- Deacon H. Towards a sustainable theory of health-related stigma: lessons from the HIV/AIDS literature. J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2006;16:418–425. [Google Scholar]

- Edlund MJ, Unutzer J, Curran GM. Perceived need for alcohol, drug, and mental health treatment. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2006;41:480–487. doi: 10.1007/s00127-006-0047-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass JE, Kristjansson SD, Bucholz KK. Perceived alcohol stigma: factor structure and construct validation. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2013;37(Suppl. 1):E237–E246. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2012.01887.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass JE, Perron BE, Ilgen MA, Chermack ST, Ratliff S, Zivin K. Prevalence and correlates of specialty substance use disorder treatment for Department of Veterans Affairs Healthcare System patients with high alcohol consumption. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;112:150–155. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF. Barriers to alcoholism treatment: reasons for not seeking treatment in a general population sample. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs. 1997;58:365–371. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1997.58.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Dawson DA, Stinson FS, Chou PS, Kay W, Pickering R. The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-IV (AUDADIS-IV): reliability of alcohol consumption, tobacco use, family history of depression and psychiatric diagnostic modules in a general population sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003;71:7–16. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(03)00070-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Goldstein RB, Chou SP, Huang B, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Saha TD, Smith SM, Pulay AJ, Pickering RP, Ruan WJ, Compton WM. Sociodemographic and psychopathologic predictors of first incidence of DSM-IV substance use, mood and anxiety disorders: results from the Wave 2 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Mol. Psychiatry. 2009;14:1051–1066. doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Kaplan KK, Stinson FS. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Bethesda, MD: 2007. Source and Accuracy Statement: Wave 2 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Chou SP, Dufour MC, Compton W, Pickering RP, Kaplan K. Prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorders and independent mood and anxiety disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2004;61:807–816. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.8.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, O’Brien CP, Auriacombe M, Borges G, Bucholz K, Budney A, Compton WM, Crowley T, Ling W, Petry NM, Schuckit M, Grant BF. DSM-5 Criteria for substance use disorders: recommendations and rationale. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2013;170:834–851. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.12060782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Kilcoyne B. Comorbidity of psychiatric and substance use disorders in the United States: current issues and findings from the NESARC. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 2012;25:165–171. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e3283523dcc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML. How does sexual minority stigma get under the skin? A psychological mediation framework. Psychol. Bull. 2009;135:707–730. doi: 10.1037/a0016441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard J. Negotiating an exit: existential, interactional, and cultural obstacles to disorder disidentification. Soc. Psychol. Q. 2008;71:177–192. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter-Reel D, McCrady BS, Hildebrandt T, Epstein EE. Indirect effect of social support for drinking on drinking outcomes: the role of motivation. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs. 2010;71:930–937. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2010.71.930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes KM, Hatzenbuehler ML, McLaughlin KA, Link BG, Olfson M, Grant BF, Hasin DS. Stigma and treatment for alcohol disorders in the United States. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2010;172:1364–1372. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King WC. Prevalence of alcohol use disorders before and after bariatric surgery. JAMA. 2012;307:2516. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.6147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroska A, Harkness SK. Stigma sentiments and self-meanings: exploring the modified labeling theory of mental illness. Soc. Psychol. Q. 2006;69:325–348. [Google Scholar]

- Laudet AB. The road to recovery: where are we going and how do we get there? Empirically driven conclusions and future directions for service development and research. Subst. Use Misuse. 2008;43:2001–2020. doi: 10.1080/10826080802293459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard KE, Kearns J, Mudar P. Peer networks among heavy, regular and infrequent drinkers prior to marriage. J. Stud. Alcohol. 2000;61:669–673. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link BG. Understanding labeling effects in the area of mental disorders: an assessment of the effects of expectations of rejection. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1987;52:96–112. [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Cullen FT. Reconsidering the social rejection of ex-mental patients: levels of attitudinal response. Am. J. Community Psychol. 1983;11:261–273. doi: 10.1007/BF00893367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Cullen FT, Frank J, Wozniak J. The social rejection of former mental patients: understanding why labels matter. Am. J. Sociol. 1987;92:1461–1500. [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Cullen FT, Struening EL, Shrout P, Dohrenwend BP. A modified labeling theory approach to mental disorders: an empirical assessment. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1989;54:400–423. [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Mirotznik J, Cullen FT. The effectiveness of stigma coping orientations: can negative consequences of mental illness labeling be avoided? J. Health Soc. Behav. 1991;32:302–320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Phelan JC. Conceptualizing stigma. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2001;27:363–385. [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Phelan JC, Bresnahan M, Stueve A, Pescosolido BA. Public conceptions of mental illness: labels, causes, dangerousness, and social distance. Am. J. Public Health. 1999;89:1328–1333. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.9.1328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Struening EL, Rahav M, Phelan JC, Nuttbrock L. On stigma and its consequences: evidence from a longitudinal study of men with dual diagnoses of mental illness and substance abuse. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1997;38:177–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livingston JD, Boyd JE. Correlates and consequences of internalized stigma for people living with mental illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc. Sci. Med. 2010;71:2150–2161. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livingston JD, Milne T, Fang ML, Amari E. The effectiveness of interventions for reducing stigma related to substance use disorders: a systematic review. Addiction. 2012;107:39–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03601.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luoma JB, O’Hair AK, Kohlenberg BS, Hayes SC, Fletcher L. The development and psychometric properties of a new measure of perceived stigma toward substance users. Subst. Use Misuse. 2010;45:47–57. doi: 10.3109/10826080902864712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luoma JB, Twohig MP, Waltz T, Hayes SC, Roget N, Padilla M, Fisher G. An investigation of stigma in individuals receiving treatment for substance abuse. Addict. Behav. 2007;32:1331–1346. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP. Contrast in multiple mediator models. In: Rose JS, Chassin L, Presson CCCC, Sherman SJ, editors. Multivariate Applications in Substance Use Research: New Methods for New Questions. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2000. pp. 141–160. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP. Introduction to Statistical Mediation Analysis. New York: Erlbaum Psych. Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Mackinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Williams J. Confidence limits for the indirect effect: distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behav. Res. 2004;39:99. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh HW, Scalas LF, Nagengast B. Longitudinal tests of competing factor structures for the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale: traits, ephemeral artifacts, and stable response styles. Psychol. Assess. 2010;22:366–381. doi: 10.1037/a0019225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin D, Long A. An extended literature review of health professionals’ perceptions of illicit drugs and their clients who use them. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 1996;3:283–288. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.1996.tb00127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moak Z, Agrawal A. The association between perceived interpersonal social support and physical and mental health: results from the National Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J. Public Health. 2010;32:191. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdp093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moses T. Self-labeling and its effects among adolescents diagnosed with mental disorders. Soc. Sci. Med. 2009;68:570–578. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller B, Nordt C, Lauber C, Rueesch P, Meyer PC, Roessler W. Social support modifies perceived stigmatization in the first years of mental illness: a longitudinal approach. Soc. Sci. Med. 2006;62:39–49. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. seventh ed. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Perlick DA. Stigma as a barrier to recovery: adverse effects of perceived stigma on social adaptation of persons diagnosed with bipolar affective disorder. Psychiatr. Serv. 2001;52:1627–1632. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.12.1627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Kelley K. Effect size measures for mediation models: quantitative strategies for communicating indirect effects. Psychol. Methods. 2011;16:93–115. doi: 10.1037/a0022658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Rucker DD, Hayes AF. Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2007;42:185–227. doi: 10.1080/00273170701341316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Selig JP. Advantages of Monte Carlo confidence intervals for indirect effects. Commun. Methods Meas. 2012;6:77–98. [Google Scholar]

- Pressman SD, Cohen S, Miller GE, Barkin A, Rabin BS, Treanor JJ. Loneliness, social network size, and immune response to influenza vaccination in college freshmen. Health Psychol. 2005;24:297–306. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.3.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roeloffs C, Sherbourne C, Unützer J, Fink A, Tang L, Wells KB. Stigma and depression among primary care patients. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry. 2003;25:311–315. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(03)00066-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfield S. Labeling mental illness: the effects of received services and perceived stigma on life satisfaction. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1997;62:660–672. [Google Scholar]

- Ruan WJ, Goldstein RB, Chou SP, Smith SM, Saha TD, Pickering RP, Dawson DA, Huang B, Stinson FS, Grant BF. The alcohol use disorder and associated disabilities interview schedule-IV (AUDADIS-IV): reliability of new psychiatric diagnostic modules and risk factors in a general population sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;92:27–36. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schomerus G, Corrigan PW, Klauer T, Kuwert P, Freyberger HJ, Lucht M. Self-stigma in alcohol dependence: consequences for drinking-refusal self-efficacy. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;114(1):12–17. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schomerus G, Lucht M, Holzinger A, Matschinger H, Carta MG, Angermeyer MC. The stigma of alcohol dependence compared with other mental disorders: a review of population studies. Alcohol Alcohol. 2010;46:105–112. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agq089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SM, Dawson DA, Goldstein RB, Grant BF. Examining perceived alcoholism stigma effect on racial-ethnic disparities in treatment and quality of life among alcoholics. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs. 2010;71:231–236. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2010.71.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 12. College Station, TX: StataCorp, LP; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Swartz HA. Depression and anxiety among mothers who bring their children to a pediatric mental health clinic. Psychiatr. Serv. 2005;56:1077–1083. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.9.1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoits PA. Self-labeling processes in mental illness: the role of emotional deviance. Am. J. Sociol. 1985;91:221–249. [Google Scholar]

- Wahl OF. Mental health consumers’ experience of stigma. Schizophr. Bull. 1999;25:467–478. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White WL. Addiction recovery: its definition and conceptual boundaries. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2007;33:229–241. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2007.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White WL. The mobilization of community resources to support long-term addiction recovery. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2009;36:146–158. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2008.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams EC, Lapham GT, Hawkins EJ, Rubinsky AD, Morales LS, Young BA, Bradley KA. Variation in documented care for unhealthy alcohol consumption across race/ethnicity in the Department of Veterans Affairs Healthcare System. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2012;36:1614–1622. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2012.01761.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright ER, Gronfein WP, Owens TJ. Deinstitutionalization, social rejection, and the self-esteem of former mental patients. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2000;41:68–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.