Abstract

Soft-tissue sarcomas of the genitourinary tract account for only 1–2% of urological malignancies and 2.1% of soft-tissue sarcomas in general. A 69-year-old male complained of a 4 month history of a painless right groin swelling during routine urological review for prostate cancer follow-up. Clinical examination revealed a non-tender, firm right inguinoscrotal mass. There was no discernible cough impulse. Computed tomography of abdomen and pelvis showed a non-obstructed right inguinal hernia. During elective hernia repair a solid mass involving the spermatic cord and extending into the proximal scrotum was seen. The mass was widely resected and a right orchidectomy was performed. Pathology revealed a paratesticular sarcoma. He proceeded to receive adjuvant radiotherapy. Only around 110 cases of leiomyosarcoma of the spermatic cord have been described in the literature. They commonly present as painless swellings in the groin. The majority of diagnoses are made on histology.

Key words: paratesticular, sarcoma, spermatic cord, leiomyosarcoma, trabectedin.

Case Report

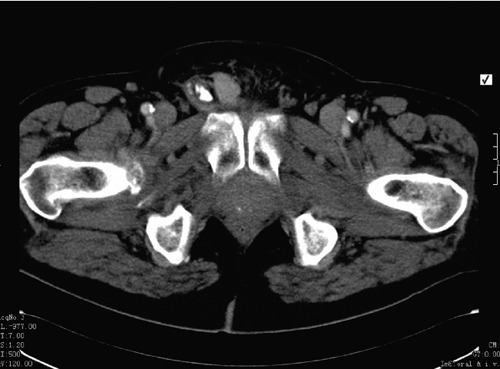

A 69-year-old male complained of a 4 month history of a progressively enlarging, painless right groin swelling during routine urological review. There was no associated lower urinary tract or constitutional symptoms. Medical history was positive for hypertension, type 2 diabetes, angina and hypercholesterolemia. He had been diagnosed with locally advanced prostate cancer 2 years previously, for which he had received radical radiotherapy (74Gy/37 fractions) and was on maintenance androgen deprivation therapy. Regular medications included atenolol, aspirin, glucophage and lipitor. Clinical examination revealed a non-tender firm right inguinoscrotal mass. There was no discernible cough impulse. Contrast computed tomography of abdomen and pelvis showed a non-obstructed right inguinal hernia containing a contrast filled loop of small bowel (Figure 1). No pelvic lymphadenopathy was seen. An elective right inguinal hernia repair was scheduled. Intra-operatively a solid mass involving the spermatic cord and extending into the proximal scrotum was seen. The mass was widely resected, and a right orchidectomy was performed. Pathology revealed a right paratesticular sarcoma, of the leiomyosarcoma type involving the spermatic cord (Figure 2). He proceeded to receive 64Gy/32 fractions of adjuvant radiotherapy.

Figure 1.

Transverse section of a contrast enhanced computed tomographic scan of the abdomen and pelvis showing a right inguinoscrotal mass.

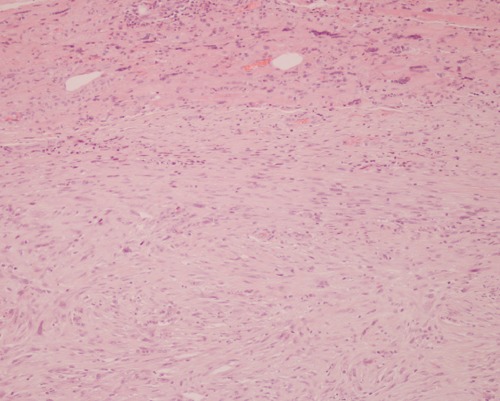

Figure 2.

Histologically the tumor appears as malignant smooth muscle spindle cells with typical cigar-shaped nuclei, which stain to alpha actin, desmin, and vimentin antibodies. ×10 magnification.

Discussion

Soft-tissue sarcomas of the genitourinary tract are uncommon, accounting for only 1–2% of urological malignancies, and 2.1% of soft-tissue sarcomas in general.1 More specifically para-testicular sarcoma; sarcomas of the spermatic cord are extremely rare. Leiomyo-sarcoma is the commonest type of paratesticular sarcoma. Only around 110 cases of leiomyosarcoma of the spermatic cord have been described in the literature.2 They may arise from the cord, scrotum or epididymis. Peak incidence is in the 6th and 7th decades. Histologically, the most common spermatic cord type arises from undifferentiated mesenchymal cells of the cremasteric muscle and vas deferens. The less frequent epididymal form arises from the smooth muscle surrounding the basement membrane of the epididymal canal.

Leiomyosarcoma may be divided anatomically into deep soft-tissue, cutaneous-subcutaneous, and vascular. The American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) classifies spermatic cord leiomyosarcoma as deep tissue.3 Modes of spread include haematogenous, lymphatic and local extension. Nodal spread can involve external iliac, hypogastric, common iliac and para-aortic nodes. Haematogenous metastases are primarily pulmonary or hepatic. The vas deferens can act as a conduit for local spread, which may involve the scrotum, inguinal canal or pelvis.

Clinical presentation is typically with a painless, firm, progressively enlarging, intra-scrotal mass which is extra-testicular. It is very challenging to diagnose paratesticular sarcoma pre-operatively. Histological examination is required for diagnosis. The differential diagnosis includes inguinoscrotal hernia, hydrocoele, testicular malignancy and other rarer tumors including benign leiomyoma, fibrous mesothelioma, various benign fibrous tumors and pseudotumors, and fibromatosis.4 Radical orchidectomy and high ligation of the spermatic cord is the standard operative intervention. Adjuvant radiotherapy aims to reduce local recurrence rates.5,6 The exact degree to which surrounding soft tissues should be resected and the optimal margin measurements remain controversial. In 27% of cases, which were completely excised, re-resection showed evidence of microscopic residual disease.6

Nodal involvement appears to be more commonly associated with paratesticular sarcoma than other soft tissue sarcomas. In two separate studies Catton and colleagues have shown nodal failure rates varying between 14% (2 of 14 patients) and 28% (6 of 21 patients).6,7 However, the literature has reported rates of up to 29%.6 Due to this high incidence of nodal recurrence, both prophylactic retroperitoneal lymph node dissection and adjunctive nodal radiotherapy have been used.8 To date there are no reports of an improvement in survival with adjunctive nodal dissection.

Several studies have shown that wide excision alone is inadequate in preventing recurrence. Local recurrence rates of 27% have been reported with wide excision alone, although the study population involved was small.5,6,9,10 The median follow-up for each was 4.2 years, with the exception of the study by Fagundes et al. It is of note that, in this study, median follow-up for non-irradiated and irradiated groups differed, being 123 and 63 months respectively. This may have lead to an artificially increased rate of recurrence in the non-irradiated group. Extensive resection may be required if negative margins are not achieved. Local recurrence has been described as the Achilles heel of sarcoma management, and spermatic cord sarcomas are no exception.10 Sarcomas of all grades have a tendency to infiltrate local tissues, leading to morbidity from local disease progression, and a higher rate of metastasis and disease-specific mortality. In one study, which looked at 102 patients with primary disease of the genitourinary tract alone, 33 developed local recurrence (median time to local recurrence being 10.6 years) with 20 sarcoma-specific deaths.10 The risk associated with sarcomas can be reduced with adjunctive radiotherapy, or adjunctive surgery as required.11

With the exception of the Dotan et al.'s study, previous attempts at examining urological sarcomas with regards to optimal management have been hindered by small cohort numbers, and the rarity of the condition.10 However, prolonged disease-specific survival has consistently been shown to be associated with tumor histology, size (<5 cm), grade, achieving complete resection, paratesticular or bladder tumor site and lack of metastases at presentation.6,10,12

The largest study of genitourinary sarcomas to date looked at 131 patients; 57 having a para-testicular sarcoma. 51% of the paratesticular patients were disease-free at the median follow-up time of 4.2 years, with 3% still showing evidence of disease, and 39% having died of the disease in the interim.10 7% of the paratesticular sarcoma patients had died of unrelated causes. Notably 18% of these patients had metastasis at the time of diagnosis. Adjunctive radio- and chemotherapy were not consistently used in this retrospective study population, and therefore their effects were not considered. This is unfortunate, as it remains to be conclusively proven that adjuvant radiation or chemotherapy is effective in para-testicular sarcomas specifically. The standard management of wide excision with adjunctive radio-therapy is based on the success of adjuvant radiotherapy in the management of sarcomas in general.11

Evidence for the routine use of adjuvant chemotherapy for adult high grade sarcoma is controversial. In 1997 the Sarcoma Meta-analysis Collaboration showed significant relapse free survival rates (median follow-up 9.4 years) with adjuvant doxorubicin in soft-tissue sarcomas (n=1568).13 However Woll et al. in the largest Phase III randomized control trial to date failed to show an improvement with chemotherapy (n=351).14 Trabectedin is the latest chemotherapeutic agent developed in the management of sarcoma. Phase I and II trials showed promising preliminary results with objective response rates between 3.7% and 17.1%. Trabectedin activity appears to be limited outside of myxoid and round cell liposarcomas. The relatively low incidence of sarcomas makes phase III trials a difficult task.15,16

Conclusions

As the majority of studies into paratesticular sarcomas are retrospective by necessity, the inconsistency of management of the patients involved makes a comparison of therapies difficult.

References

- 1.Stojadinovic A, Leung DH, Allen P, et al. Primary adult soft tissue sarcoma: time-dependent influence of prognostic variables. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:4344–52. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.07.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vogelaar FJ, Schuttevaer HM, Willems JM. A patient with an inguinal mass: a groin hernia? Neth J Med. 2009;67:399–400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Folpe AL, Weiss SW. Paratesticular soft tissue neoplasms. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2000;17:307–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fisher C, Goldblum JR, Epstein JI, Montgomery E. Leiomyosarcoma of the paratesticular region: a clinicopathologic study. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:1143–9. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200109000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fagundes MA, Zietman AL, Althausen AF, et al. The management of spermatic cord sarcoma. Cancer. 1996;77:1873–6. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19960501)77:9<1873::AID-CNCR17>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Catton C, Jewett M, O'Sullivan B, Kandel R. Paratesticular sarcoma: failure patterns after definitive local therapy. J Urol. 1999;161:1844–7. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(05)68823-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Catton C, Cummings BJ, Fornasier V, et al. Adult paratesticular sarcomas: a review of 21 cases. J Urol. 1991;146:342–5. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)37787-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Banowsky LH, Schultz GN. Sarcoma of spermatic cord and tunics: review of literature, case report and discussion of role of retroperitoneal lymph node dissection. J Urol. 1970;103:628–31. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)62016-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rabbani F, Wright JE, McLoughlin MG. Sarcomas of the spermatic cord: significance of wide local excision. Can J Urol. 1997;4:366–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dotan ZA, Tal R, Golijanin D, et al. Adult genitourinary sarcoma: the 25-year Memorial Sloan-Kettering experience. J Urol. 2006;176:2033–8. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bauer HC, Alvegard TA, Berlin O, et al. The Scandinavian Sarcoma Group Register 1986–2001. Acta Orthop Scand Suppl. 2004;75:8–10. doi: 10.1080/00016470410001708260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Russo P, Brady MS, Conlon K, et al. Adult urological sarcoma. J Urol. 1992;147:1032–6. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)37456-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adjuvant chemotherapy for localized resectable soft-tissue sarcoma of adults: meta-analysis of individual data. Sarcoma Meta-analysis Collaboration. Lancet. 1997;350:1647–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Woll PJ, Van Glabbeke M, Hohenberger P, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy (CT) with doxorubicin and ifosfamide in resected soft tissue sarcoma (STS): interim analysis of a randomised phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(Suppl 18):10008–10008. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thornton KA. Trabectedin: the evidence for its place in therapy in the treatment of soft tissue sarcoma. Core Evid. 2010;4:191–8. doi: 10.2147/ce.s5993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yuen VT, Kirby SD, Woo YC. Leiomyosarcoma of the epididymis: 2 cases and review of the literature. Can Urol Assoc J. 2011;5:E121–4. doi: 10.5489/cuaj.11008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]