Abstract

Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1) is a heterodimeric transcription factor that governs cellular responses to reduced oxygen availability by mediating crucial homeostatic processes and is a major survival determinant for tumor cells growing in a low oxygen environment. Clinically, HIF-1α appears to be important in pancreatic cancer, as HIF-1α correlates with metastatic status of the tumor. Extracellular superoxide dismutase (EcSOD) inhibits pancreatic cancer cell growth by scavenging non-mitochondrial superoxide. We hypothesized that EcSOD overexpression leads to changes in the O2•−/H2O2 balance modulating the redox status affecting signal transduction pathways. Both transient and stable overexpression of EcSOD suppressed the hypoxic accumulation of HIF-1α in human pancreatic cancer cells. This suppression of HIF-1α had a strong inverse correlation with levels of EcSOD protein. Co-expression of the hydrogen peroxide-removing protein, glutathione peroxidase (GPx), did not prevent the EcSOD-induced suppression of HIF-1α, suggesting that the degradation of HIF-1α observed with high EcSOD overexpression is possibly due to a low steady-state level of superoxide. Hypoxic induction of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) was also suppressed with increased EcSOD. Intratumoral injections of an adenoviral vector containing the EcSOD gene (AdEcSOD) into pre-established pancreatic tumors suppressed both VEGF levels and tumor growth. These results demonstrate that the transcription factor HIF-1α and its important gene target VEGF can be modulated by the antioxidant enzyme EcSOD.

INTRODUCTION

Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1) is a transcriptional regulator that functions in the adaptation of tumor cells to hypoxic conditions. HIF-1 binds to DNA at specific hypoxia response elements (HRE) to activate the transcription of more than 100 genes involved in cellular response to hypoxia [1]. Clinically HIF-1α appears to be important in pancreatic cancer survival. Using immunohistochemical methods, Sun et al. demonstrated that HIF-1α in pancreatic cancer specimens strongly impacts prognosis and correlates with vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) expression [2]. Hoffman et al. demonstrated that pancreatic cancer specimens with high HIF-1α expression were associated with decreased patient survival when compared to pancreatic cancers with low HIF-1α expression [3]. They also revealed a positive correlation of HIF-1α with VEGF levels, lymph node metastasis, and tumor size. Similarly, Shibaji et al. demonstrated that HIF-1α positivity in pancreatic cancer correlated with metastatic status [4]. In pancreatic cancer Buchler and colleagues demonstrated that in hypoxia, HIF-1α binds to the VEGF promoter with high specificity; this binding correlated with levels of VEGF [5]. Taken together, these studies suggest that HIF-1α appears to be an important factor in pancreatic cancer progression and metastasis.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS), including superoxide (O2•−) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), play a role in altering HIF-1α signaling [6, 7, 8, 9, 10]. Extracellular superoxide dismutase (EcSOD; SOD3) modulates ROS by facilitating the conversion of O2•− to H2O2, which is subsequently reduced to water by the activities of catalase or peroxidases [11]. EcSOD is a copper and zinc-containing tetramer and is the only isoform of superoxide dismutase that is secreted extracellularly. It contains a signaling peptide, which directs it to the extracellular space, and a heparin-binding domain (HBD), allowing it to bind to cell surfaces in the extracellular matrix [12, 13]. Thus, EcSOD may be able to modulate oxidative stress present in the tumor microenvironment. Our working hypothesis is that EcSOD overexpression leads to changes in the O2•−/H2O2 balance [14], modulating the redox status and affecting signal transduction pathways that control cell proliferation, growth, and metastases. Here we demonstrate that overexpression of EcSOD inhibits hypoxic pancreatic cancer cell growth and suppresses the hypoxic accumulation of HIF-1α and its downstream target VEGF.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Culture

All pancreatic cancer cells were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA) and passaged for fewer than six months after receipt and maintained as previously described [14]. No additional authentication was performed. H6c7 is an immortalized cell line derived from normal pancreatic ductal epithelium with near normal genotype and phenotype of pancreatic duct epithelial cells [15]. H6c7 cells were maintained in keratinocyte serum free media that was supplemented with epidermal growth factor and bovine pituitary extract. The H6c7 cells were characterized by IDEXX-RADIL (Columbia, MO).

Adenovirus Gene Transfer

The adenovirus constructs used expressed either human EcSOD (AdEcSOD) or human EcSOD with the heparin-binding domain deleted (AdEcSODΔHBD) which was inserted into the E1 region of the adenovirus genome and driven by a cytomegalovirus promoter [14]. The vector control consisted of the same adenovirus with either no gene added (AdEmpty) or adenovirus containing no added DNA (AdBglII). In addition, we used an adenoviral vector expressing siRNA against NOX2 (AdsiNOX2), which was prepared and characterized by Dr. Robin Davisson [16] and constructed, purified, and provided by The University of Iowa Gene Vector Core. The AdEcSOD and the AdEmpty constructs were purchased from ViraQuest (North Liberty, IA), while the AdBglII vector was purchased from the University of Iowa Gene Vector Core.

Retrovirus preparation and infection protocol

A plasmid (#100004716) containing the EcSOD gene was purchased from Open Biosystems (Lafayette, CO) and subcloned into the expression vector, pQXCIN by ViraQuest (North Liberty, IA). The orientation as well as sequence analysis of the final product was performed by ViraQuest. The expression vector was co-tranfected into GP2-293 packaging cells along with a plasmid containing pVSV-G using the Retroviral Gene Transfer and Expression Kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Clonetech, Mountain View, CA). The collected virus was used to infect the MIA PaCa-2 target cells. G418-resistant colonies were isolated in 96-well plates and maintained in media supplemented with 600 μg/mL of G418 Sulfate (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY). Clones were characterized by Western blot analysis for EcSOD expression with those selected for further study showing a wide range of EcSOD protein expression.

EcSOD Activity

EcSOD activity gels were determined by the method of Beauchamp and Fridovich [17]. To quantitatively determine the EcSOD activity released into the media (over 24 h) by MIA PaCa-2 clones that stably overexpress EcSOD, we adapted the assay of Spitz and Oberley [18] to a 96-well plate format; water-soluble tetrazolium-1 (WST-1) was used as the chromophore [19]. The concentration of EcSOD in the media was determined by performing a kinetic analysis of the competitive reduction of WST-1 using kEcSOD = 4.0×109 M−1 s−1 for the rate constant for the tetrameric form of EcSOD reacting with O2•− and kWST−1 = 5.9 × 105 M−1 s−1 for WST-1 reacting with O2•−. Cell numbers and volume of media over the cells allowed determination of the average rate of release of fully active EcSOD tetramers into the media on a per cell basis. For the assay, media from the cells was serially diluted yielding 12 different concentrations. Because the serum in the culture media may contain SOD activity, media that was not exposed to cells was included in the assay to provide baseline activity levels. These solutions, as well as a set of CuZnSOD standards, were mixed with the working solution of the assay to achieve final concentrations in 50 mM potassium phosphate (pH 7.8) of: 1 mM diethyltriaminepentaacetic acid, 52 μg/mL BSA, 100 U/mL bovine liver catalase, 440 μM hypoxanthine, 51 μM bathocuproinedisulfonic acid, and 10 μM WST-1 as the indicting chromophore. Then xanthine oxidase, which initiates the assay, was added to yield a final concentration of 3 mU/mL. Kinetic data were collected with a Tecan Infinite 200 microplate reader. Relative EcSOD concentrations were also confirmed with activity gels.

Protein Turnover Assays

To determine whether EcSOD had an effect on HIF-1α protein synthesis or protein degradation, cells were treated with the protein synthesis inhibitor cycloheximide or the proteasomal inhibitor MG-132. MIA PaCa-2 cells were plated and incubated in 21% O2. Cells were transduced with AdEcSOD or AdEmpty as described above. To examine new protein synthesis, cells were treated with MG-132 (10 μM; EMD Chemicals, San Diego, CA) added to the media at time 0 and incubated in hypoxia (4% O2). To examine protein degradation, cells were pre-incubated in 4% O2 for 4 h to allow HIF-1α protein accumulation. At time 0, cycloheximide (100 μM; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was added, and cell lysates were harvested at the appropriate time points for Western blot analysis.

VEGF Assay

The relative amounts of secreted VEGF expressed were determined using a commercially available ELISA assay (R & D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). The VEGF165 isoform levels were quantified in the conditioned media in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocol and measured spectrophotometrically at 450 nm with wavelength correction measured at 540 nm.

Animal Studies

Athymic nude mice were obtained from Harlan Laboratories (Indianapolis, IN). The nude mice protocol was reviewed and approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of The University of Iowa and was in compliance with The U.S. Public Health Service Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH). Each experimental group consisted of 5–8 mice. MIA PaCa-2 tumor cells (3 × 106) were delivered subcutaneously into the flank region of the nude mice. The tumors were allowed to grow until they reached between 3–4 mm in greatest dimension (2 weeks), at which time they were treated with adenovirus. The adenovirus constructs (1 × 109 plaque-forming units (PFU) in 50 μL) were delivered through two injection sites into the tumor by means of a 25-gauge needle. Controls (50 μL of 3% sucrose), AdEmpty (50 μL of A195), or AdEcSOD (50 μL of AdEcSOD construct) treatment were delivered to the tumor on days 0, 7, and 14 for a total of 3 injections. We have previously demonstrated efficiency of viral construct delivery to tumors with this method using an AdGFP construct and fluorescence microscopy [23]. Tumor size was measured every 3–4 days [20]. In separate groups of animals, tumors were excised at 48 and 96 hours after adenoviral injection. The tumor tissues were sectioned into 10 μm thick sections and exposed to VEGF antibody (1:1000, AbCam, Cambridge, MA) for 1 h. Similarly, additional sections were blocked with normal donkey serum and exposed to CD31 antibody (1:100, Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., Santa Cruz, CA) for 1 h. The secondary antibody goat anti-rabbit conjugated to Alexa Fluor® 488 (1:500) was used as a fluorescent marker for VEGF or CD31. Nuclei were counterstained using TO-PRO-3 (1:2000). Slides were mounted in Vectashield® and analyzed on Bio-Rad Radiance 2100 confocal multi-photon microscope with laser sharp software. In addition to the pre-established pancreatic tumors treated with intratumoral injections of adenovirus, we injected separate mice with MIA PaCa-2 cells (2 × 106) or with cells that were generated that stably overexpress the EcSOD gene. Tumor size was measured every week for four weeks.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses for the in vitro studies were performed using SYSTAT. A single factor ANOVA, followed by post-hoc Tukey test, was used to determine statistical differences between means. All means were calculated from three experiments, and error bars represent standard error of mean (SEM). All western blots, activity assays, and activity gel assays were repeated at least twice. For the in vivo studies, the statistical analyses focused on the effects of different treatments on cancer progression. The primary outcome of interest was tumor growth over time. Tumor sizes (mm3) were measured throughout the experiments, resulting in repeated measurements across time for each mouse. A generalized estimating equations model was used to estimate and compare group-specific tumor growth curves. Pairwise comparisons were performed to identify specific group differences in the growth curves. All tests were two-sided and carried out at the 5% level of significance. Analyses were performed with SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc. Cary, NC).

RESULTS

EcSOD overexpression inhibits hypoxic pancreatic cancer cell growth

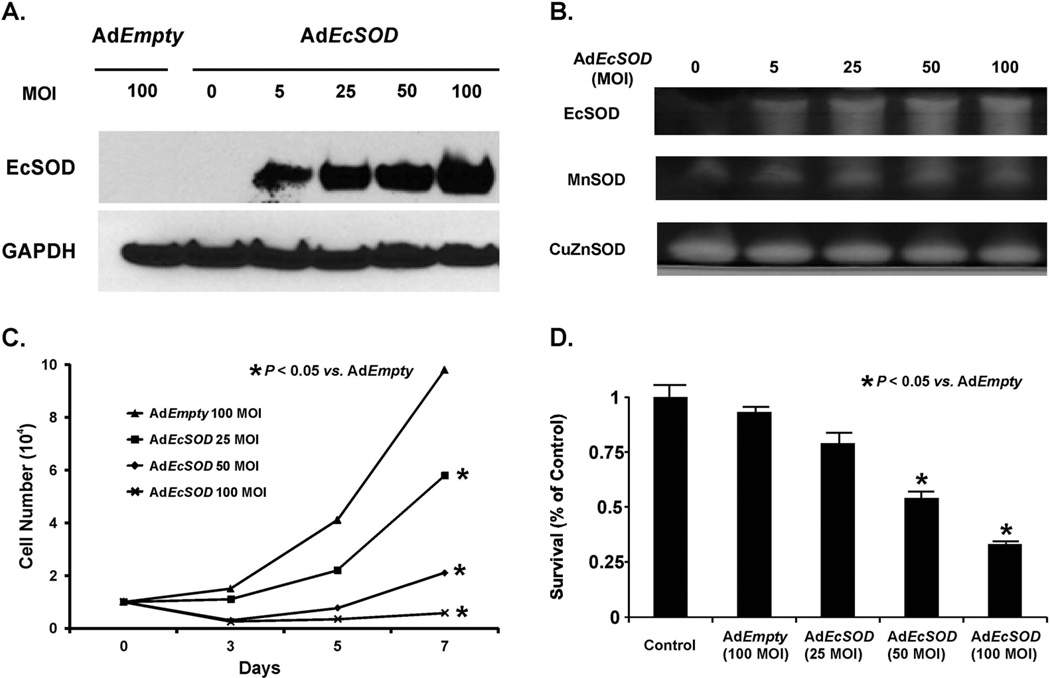

Previous studies have demonstrated that the overexpression of EcSOD did not affect growth rates in B16-F1 melanoma cells in vitro but did inhibit growth in vivo [21]. To test the effect of transient overexpression of EcSOD, the human pancreatic cancer cell lines MIA PaCa-2 and AsPC-1 were infected with AdEcSOD or AdEmpty vectors (5–100 MOI). After transduction, the cells were incubated in 21% oxygen, exposed to hypoxia (4% O2) for 24 h, and then protein lysates were collected. Western blot analysis and gel activity assays were performed, which demonstrated no detectable levels of EcSOD in wild type parental or AdEmpty (100 MOI) infected cells. However, there were increased levels of EcSOD protein (Figure 1A) and activity (Figure 1B) in AdEcSOD (25–100 MOI) infected cells without concomitant changes in levels of MnSOD or CuZnSOD activity.

Figure 1. Adenoviral transduction of EcSOD inhibits hypoxic pancreatic cancer cell growth.

A. Western blot analysis demonstrates increases in EcSOD immunoreactivity of adenoviral infected MIA PaCa-2 pancreatic cancer cells with increasing MOI. AdEmpty (100 MOI) as a negative control or AdEcSOD (0–100 MOI) was applied to cells for 24 h in 21% O2. Cells were exposed to 4% O2. Western blot demonstrates no detectable EcSOD immunoreactivity in the AdEmpty (100 MOI) or non-infected cells (0 MOI) but direct increases in EcSOD immunoreactivity with increasing MOI.

B. SOD enzymatic activities of adenoviral infected MIA PaCa-2 cells. Total cell lysate was assayed for SOD activities demonstrating increases in EcSOD activity with increasing viral titer but no changes in either the CuZnSOD or MnSOD activities.

C. AdEcSOD inhibited cell growth in 4% O2. MIA PaCa-2 cells were treated with AdEmpty (100 MOI) or AdEcSOD (25–100 MOI). Increasing viral titers of AdEcSOD inhibited cell growth. Each point represents the mean of three separate experiments. Mean ± SEM, n = 3. p < 0.05 vs. 100 MOI AdEmpty.

D. AdEcSOD inhibits clonogenic survival. MIA PaCa-2 cells were treated with AdEcSOD (25–100 MOI) and cultured for 14 days in 4% O2. Increasing viral titers decreased clonogenic survival with significant reductions at AdEcSOD 50 and 100 MOI compared to AdEmpty 100 MOI. Each point represents the mean of three separate experiments. Mean ± SEM, n = 3. p < 0.05 vs. 100 MOI AdEmpty.

Next, the effect of transient EcSOD overexpression on hypoxic cell growth was examined. MIA PaCa-2 cells were treated with increasing MOI of AdEcSOD and grown in 4% O2. Increasing MOI of AdEcSOD transduction led to significant cell growth inhibition (Figure 1C) as well as decreased clonogenic survival (Figure 1D) when compared to the parental cells or cells transduced with 100 MOI AdEmpty. The doubling time of cells infected with the AdEmpty vector was 18.2 ± 1.5 h (mean ± SEM, n = 3) vs. 62.0 ± 0.7 h (mean ± SEM, n = 3, p < 0.05) for cells infected with 100 MOI AdEcSOD. Likewise, clonogenic survival was 93% in AdEmpty treated cells compared to 33 % in AdEcSOD treated cells. Similar effects on cell growth and clonogenic survival were seen when experiments were repeated in a second pancreatic cancer cell line, AsPC-1 (Supplemental Figures 1A, 1B).

Transient overexpression of EcSOD decreases HIF-1α protein levels

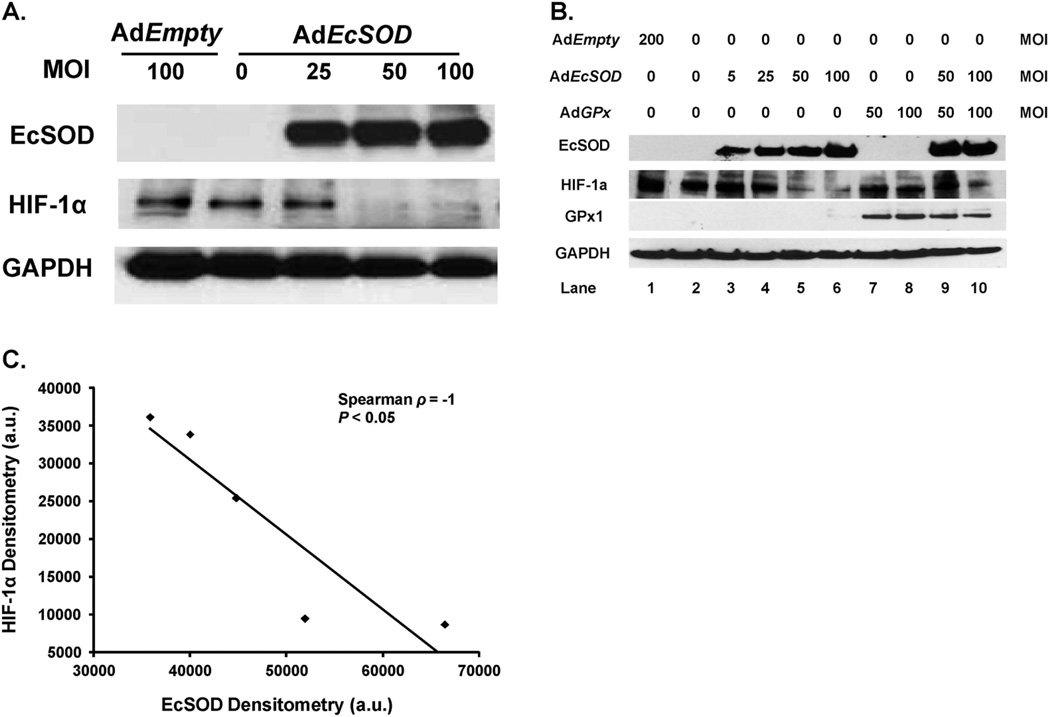

We hypothesized that alteration of the cellular redox environment associated with changes in expression of EcSOD may lead to altered HIF-1α signaling. Western blot analysis and activity gels demonstrated that infection with AdEcSOD decreased HIF-1α immunoreactive protein in MIA PaCa-2 human pancreatic cancer cells (Figure 2A). In addition, overexpression of EcSOD began to inhibit HIF-1α protein at the 25 MOI level and significantly decreased HIF-1α at the 50 and 100 MOI levels. These experiments were repeated with similar results in the AsPC-1 cells (Supplemental Figure 2). Hypoxic HIF-1α expression in the pancreatic cancer cells was transient. When MIA PaCa-2 cells were placed in 21% O2, there was no HIF-1α expression (Supplemental Figure 3). Placement of cells in 4% O2 for 24 h and then in 21% O2 reversed HIF-1α induction. Additionally, 4% O2 conditions proved to be optimal for HIF-1α induction compared to 1% O2 (Supplemental Figure 4).

Figure 2. EcSOD modulates HIF-1α accumulation in pancreatic cancer cells.

A. Human pancreatic cancer cells were infected with the AdEcSOD or AdEmpty vectors and exposed to 4% O2. Protein was harvested for EcSOD and HIF-1α Western blot analysis. EcSOD inhibited HIF-1α accumulation in MIA PaCa-2 human pancreatic cancer cells.

B. EcSOD-induced decreases in HIF-1α protein accumulation were not reversed with GPx. Western analysis of MIA PaCa-2 cells infected with the AdEmpty, AdGPx, and AdEcSOD vectors or combinations. To equalize the viral load of the combined virus in these experiments, the AdEmpty vector was given. For example, the 50 MOI AdGPx was given along with 50 MOI AdEmpty to equal the viral load of the combination of AdGPx (50 MOI) + AdEcSOD (50 MOI). The EcSOD overexpression-induced inhibition of HIF-1α accumulation was not reversed with overexpression of GPx.

C. Inverse correlation between EcSOD immunoreactive protein and HIF-1α protein accumulation in MIA PaCa-2 cells. HIF-1α protein levels were quantified by densitometry using Image J analysis (V1.43i). Spearman correlation coefficient demonstrates a significant inverse relationship. Five points are shown here. Lanes 1, 3, 4, 5 and 6 from Figure 2B were used in the analysis.

An increase in EcSOD activity will decrease the steady-state level of O2•− , but may or may not increase the levels of H2O2 , depending on the source of superoxide [14, 30]. Both O2•− and H2O2 may play a role in altering HIF-1α signaling since change attributable to accumulation of H2O2 or other hydroperoxides possibly explains the suppression of HIF-1α signaling observed in EcSOD-overexpressing cells [6, 9, 10]. To determine whether the EcSOD-induced HIF-1α suppression was due to decreased O2•− levels or increased H2O2 levels, glutathione peroxidase (GPx) was also overexpressed in MIA PaCa-2 cells. EcSOD, but not GPx, inhibited HIF-1α accumulation (Figure 2B). Increasing viral MOI of AdEcSOD correlated with increased EcSOD protein and with a subsequent decrease in HIF-1α protein accumulation. Moreover, the EcSOD-induced suppression of HIF-1α was not reversed in cells that were infected with both AdEcSOD and AdGPx in cells grown in 4% O2. Cells infected with the AdEcSOD vector demonstrated a significant inverse correlation between EcSOD and HIF-1α, using densitometric analysis (Spearman ρ = −1.0, P < 0.05) (Figure 2C). Combined, these results suggest that the HIF-1α suppression by EcSOD may be due to the decreased levels of O2•− and not due to increased levels of H2O2 or other hydroperoxides.

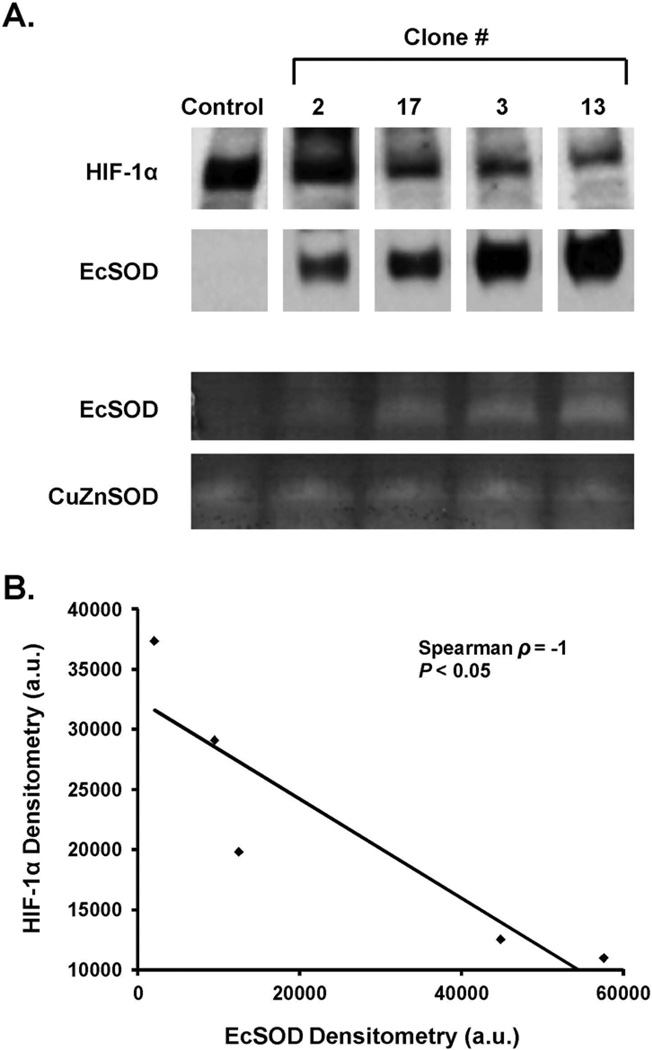

Stable overexpression of EcSOD decreases HIF-1α protein levels

In order to confirm with a second approach that EcSOD suppresses hypoxic HIF-1α protein accumulation, the previous experiments were repeated with clones stably overexpressing EcSOD. Firstly, pancreatic cancer cell lines were tested for the presence of EcSOD, including MIA PaCa-2, AsPC-1, and PANC-1, as well as an immortalized pancreatic ductal epithelial cell line, H6c7 [15]. The cells were examined for EcSOD gene expression by qPCR. Cells were incubated at 21% or 4% O2. RNA was isolated and used to generate cDNA. Amplification was carried out to 35 cycles; there was no expression of the EcSOD gene demonstrated in any of the cell lines, while an appropriate signal was seen in a positive control obtained from lung tissue (data not shown). Furthermore, HIF-1α mRNA expression remained constant at both 21% and 4% O2 in all of the cell lines.

Since there is no basal expression of EcSOD in these pancreatic cancer cell lines, to test the effect of EcSOD on HIF-1α levels in pancreatic cancer, stable clones that overexpress EcSOD were generated. Clones were examined by Western blot analysis for EcSOD expression, and those chosen for further study demonstrated varying degrees of EcSOD protein expression. In the first series of experiments, clones #2, 17, 3 and 13 were chosen. In these clones, EcSOD protein correlated well with EcSOD activity (Figure 3A). In addition, increasing stable expression of EcSOD protein decreased HIF-1α protein levels. The data in Figure 3B demonstrate a significant inverse correlation between EcSOD and HIF-1α using densitometric analysis (Spearman ρ = −1.0, P < 0.05). Combined with previous data demonstrating the effects of transient overexpression of EcSOD on HIF-1α, these results further support the hypothesis that EcSOD suppresses HIF-1α accumulation.

Figure 3. HIF-1α protein accumulation is decreased in cells with stable overexpression of EcSOD immunoreactive protein.

A. Cells of different stable clones expressing varying levels of EcSOD were exposed to 4% O2 for 24 h and protein was harvested for EcSOD activity gel assay. CuZnSOD activity was used as a loading control. EcSOD protein correlated with EcSOD activity without changes in CuZnSOD activity.

B. There is an inverse relationship between EcSOD protein and HIF-1α protein accumulation in MIA PaCa-2 cells that stably express varying amounts of EcSOD protein. HIF-1α and EcSOD protein levels were quantified by densitometry using Image J analysis. Spearman correlation coefficient demonstrates a significant inverse relationship.

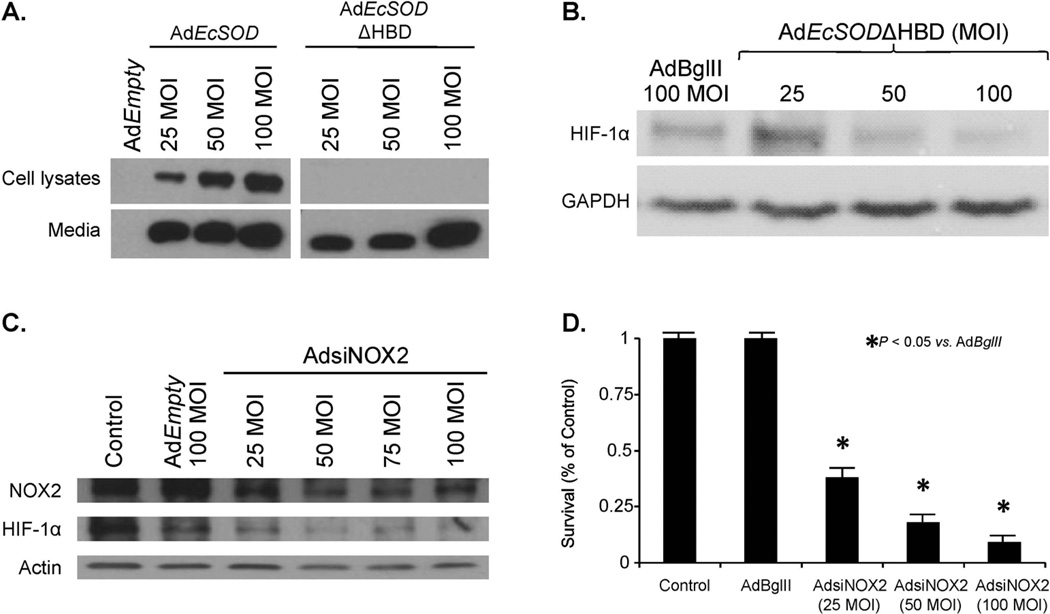

EcSOD contains a positively charged heparin-binding domain that mediates the binding of EcSOD to the cell membrane [22]. To further delineate the role of extracellular O2•− in HIF-1α accumulation, we used a replication-deficient adenoviral vector that expresses EcSOD with deletion of its heparin binding domain, AdEcSODΔHBD. When compared to the AdEcSOD vector, AdEcSODΔHBD increased EcSOD immunoreactive protein in the media but not in the cell lysates (Figure 4A). This increased expression of AdEcSODΔHBD also resulted in significant suppression of hypoxia induced HIF-1α accumulation (Figure 4B) and decreases in clonogenic cell survival in hypoxia (Supplemental Figure 5).

Figure 4. Non-mitochondrial superoxide alters HIF-1α protein accumulation.

A. MIA PaCa-2 cells were infected with the AdEmpty, AdEcSOD, or EcSOD with deletion of its heparin binding domain, AdEcSODΔHBD, and exposed to 4% O2. Western blot analysis once again demonstrated overexpression of EcSOD in cells treated with AdEcSOD. However, in cells treated with AdEcSODΔHBD there was an absence of cellular increases in EcSOD but EcSOD was increased in the media.

B. AdEcSODΔHBD inhibits HIF-1α accumulation. Cells were infected with the AdEcSOD, AdEcSODΔHBD or AdBglII vectors and exposed to 4% O2. Overexpression of EcSOD with AdEcSODΔHBD inhibited HIF-1α accumulation in MIA PaCa-2 human pancreatic cancer cells.

C. An adenoviral vector expressing siRNA against NOX2 (AdsiNOX2) was transfected into the MIA PaCa-2 pancreatic cancer cell line and grown in 4% oxygen. AdsiNOX2 (25–100 MOI) decreased immunoreactive protein when compared to both the parental cell line and cells transfected the adenoviral control vector AdEmpty (100 MOI). In addition to knockdown of NOX2, there was an inhibition of HIF-1α accumulation in cells treated with the AdsiNOX2 vector.

D. AdsiNOX2 infection (25–100 MOI) in MIA PaCa-2 cells decreased surviving fraction when compared to the same cell line infected with the AdBglII vector (100 MOI). Each point represents the mean values, with p < 0.05 vs. AdBglII, n = 3.

Recent studies from our laboratory have demonstrated that a possible non-mitochondrial source of O2•− in pancreatic cancer cells is NADPH oxidase-2 (NOX2) [23]. Superoxide produced by NOX2 in pancreatic cancer cells with K-ras may regulate pancreatic cancer cell growth. To further define the role of O2•− in HIF-1α accumulation we used the AdsiNOX2 vector and determined protein levels of NOX2 and HIF-1α, and clonogenic survival. In MIA PaCa-2 cells, AdsiNOX2 (50–100 MOI) significantly decreased NOX2 immunoreactive protein (Figure 4C). AdsiNOX2 also decreased HIF-1α accumulation in cells grown in 4% oxygen (Figure 4C), which was accompanied by decreases in clonogenic survival (Figure 4D) in a similar pattern as seen with EcSOD overexpression. These data suggest that non-mitochondrial O2•− can increase the accumulation of HIF-1α in pancreatic cancer cells; EcSOD, which can scavenge this O2•−, suppresses this accumulation of HIF-1α.

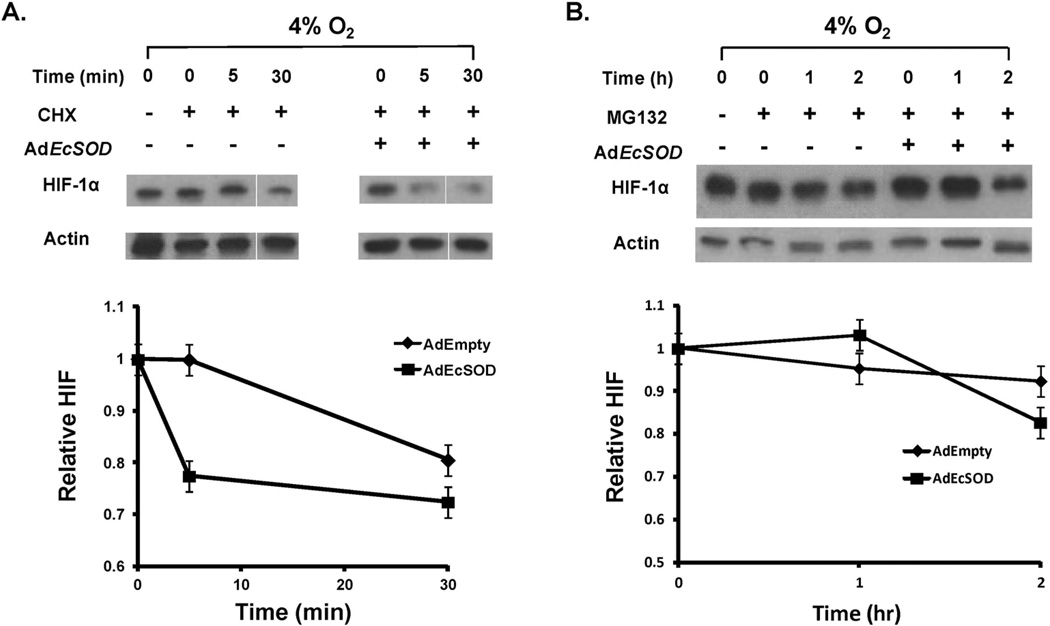

EcSOD increases the rate of HIF-1α protein degradation

To further investigate how EcSOD inhibits HIF-1α expression, we tested whether the degradation of HIF-1α protein was affected by EcSOD in the presence of cycloheximide, an inhibitor of protein translation. MIA PaCa-2 cells that had been infected with either the AdEmpty or AdEcSOD vector (100 MOI) were pre-incubated in hypoxia for 4 h to increase HIF-1α levels and then treated with cycloheximide. In hypoxia, HIF-1α degraded more rapidly in the AdEcSOD treated cells compared to the AdEmpty treated cells (Figure 5A). These results indicate that EcSOD suppresses the levels of HIF-1α protein in hypoxic conditions through a post-translational mechanism [24].

Figure 5. EcSOD increases the rate of HIF-1α protein degradation.

A. AdEcSOD increases the degradation rate of HIF-1α protein. MIA PaCa-2 cells were treated with cycloheximide (100 μM) to inhibit protein synthesis. The levels of HIF-1α protein and β-actin with either AdEmpty or AdEcSOD (100 MOI) were analyzed after exposure to 4% O2. The degradation rate of HIF-1α was increased by overexpression of EcSOD.

B. EcSOD did not affect HIF-1α protein synthesis. MIA PaCa-2 cells were treated with MG-132 (10 μM) to inhibit protein degradation through the proteasome. Levels of HIF-1α and β-actin in cells treated with either AdEmpty or AdEcSOD infection were determined over a period of 2 h. The amount of HIF-1α protein was unchanged in the presence of MG-132 after treatment with EcSOD.

Next we examined whether EcSOD could regulate HIF-1α protein synthesis. MIA PaCa-2 cells were treated with MG-132, a proteasome inhibitor, to interrupt HIF-1α proteasomal degradation. MG-132 was added to cell culture medium at 0 h, and HIF-1α protein was detected over time. In hypoxia, there was no difference in HIF-1α protein after 2 h when AdEmpty treated cells were compared with AdEcSOD treated cells (Figure 5B). In addition, quantitative PCR showed that HIF-1α mRNA expression was not affected by EcSOD. Overall these results suggest that EcSOD inhibits HIF-1α protein accumulation in hypoxia at the post-translational level by increasing HIF-1α protein degradation, while there is no effect on HIF-1α mRNA expression or HIF-1α protein synthesis.

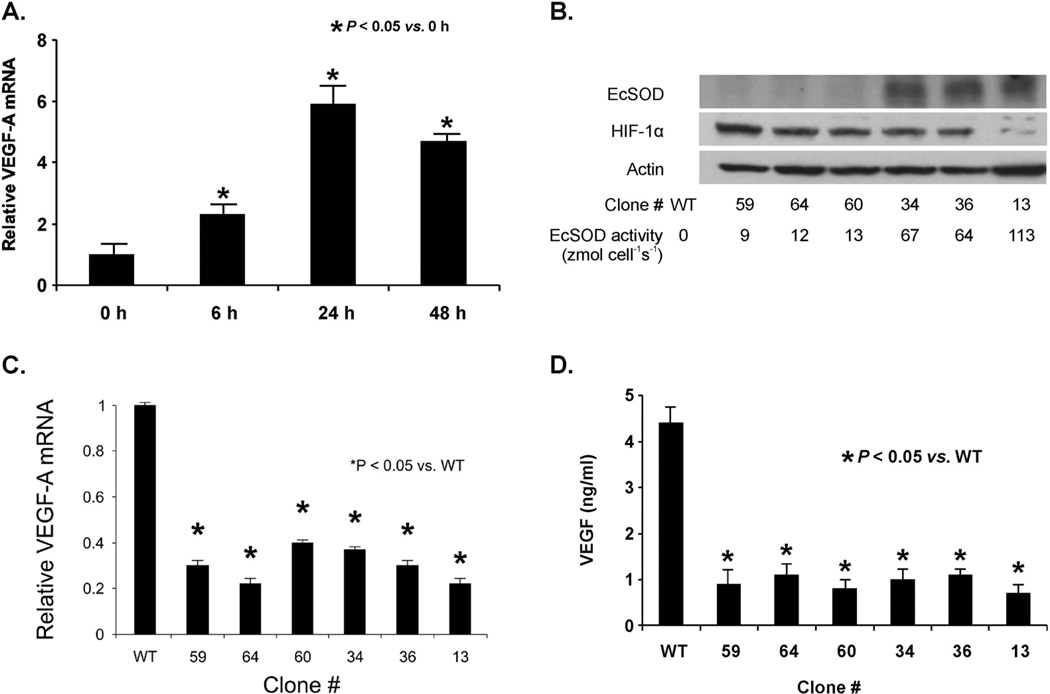

Hypoxia-induced VEGF is decreased with EcSOD

Angiogenesis is a key step that supports tumor growth but also provides a route for cells to metastasize [25]. VEGF is a potent angiogenic stimulant [26]. Exposure to hypoxia stimulates the production of VEGF mainly through the induction of the transcription factor HIF-1α [27]. Since EcSOD suppressed hypoxic accumulation of HIF-1α protein, the effect of EcSOD activity on hypoxic induction of VEGF in pancreatic cancer cells was also measured. Wild-type MIA PaCa-2 cells were grown in hypoxia (4% O2), lysed, and total RNA was isolated for qPCR measurements using the primers described in Materials and Methods. VEGF-A mRNA expression increased significantly after cells were exposed to hypoxia for 6 h (Figure 6A). This induction continued in cells exposed for longer times. However, HIF-1α mRNA expression remained stable (data not shown), confirming that HIF-1α protein levels are modulated post-transcriptionally rather than by decreased mRNA expression.

Figure 6. EcSOD overexpression suppressed hypoxic induction and secretion of VEGF.

A. Hypoxia increased the induction of VEGF-A mRNA in MIA PaCa-2 cells. Cells were grown in 4% O2 for 48 h. RNA was extracted, and qPCR was performed using GAPDH as a control to quantitate relative expression of VEGF. In 4% O2, VEGF mRNA expression relative to control cells grown in 21% O2 was increased in a time-dependent manner.

B. Increases in EcSOD protein and activity inhibit HIF-1α protein accumulation in various MIA PaCa-2 cell-clones that stably express varying amounts of EcSOD protein. EcSOD activity is represented by the rate of EcSOD synthesis and release of active tetrameric EcSOD into the media in units of zeptomole cell−1 s−1.

C. EcSOD overexpression suppressed VEGF-A mRNA in all MIA PaCa-2 clones that overexpress EcSOD. Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of VEGF-A expression in different EcSOD-overexpressing clones subjected to 24 h of hypoxia illustrates a consistent reduction in induction of VEGF-A in all cells. This is not dependent on EcSOD protein or activity. Mean ± SEM, n = 3, p < 0.05 vs. wild-type (WT).

D. Overexpression of EcSOD suppressed VEGF protein secretion in MIA PaCa-2 cells. VEGF protein was measured in cell lysates after 24 h of hypoxia (4% O2) in six different clones with various EcSOD activities. Mean ± SEM, n = 3, p < 0.05 vs. WT.

Since VEGF-A mRNA expression increased significantly with hypoxia, we also determined whether increasing EcSOD activity would affect VEGF-A mRNA expression in hypoxia. Because HIF-1α accumulation leads to VEGF expression and EcSOD suppresses HIF-1α, we hypothesized that EcSOD would also modulate VEGF. Indeed, stable EcSOD transduction inhibited VEGF-A expression with hypoxic exposure. After exposure to 4% O2 for 24 h, HIF-1α decreased with increasing amounts of EcSOD immunoreactive protein and EcSOD activity (Figure 6B). VEGF-A mRNA expression was induced in parental cells. However, qPCR demonstrated that VEGF-A expression in wild type cells was significantly higher when compared to all clones that stably overexpressed EcSOD (Figure 6C). This suggests there is a potential threshold level of EcSOD, whereupon EcSOD can completely inhibit VEGF-A mRNA expression. As a mitogenic cytokine, VEGF protein is secreted outside the cells to stimulate the proliferation of endothelial cells [28].

To determine if VEGF protein secretion followed the trends of EcSOD-induced suppression of VEGF mRNA expression, the pattern of VEGF protein secretion with hypoxic stimulation was examined. MIA PaCa-2 cells transfected with AdEcSOD and stable clones overexpressing EcSOD were grown in hypoxia (4% O2), and media were collected. Consistent with the results showing suppressed levels of VEGF-A mRNA in hypoxia after overexpression of EcSOD, VEGF concentrations in media were also decreased in both the AdEcSOD treated cells (Supplemental Figure 6) and all clones overexpressing EcSOD (Figure 6D). This demonstrates that decreasing VEGF mRNA expression by suppressing levels of HIF-1α protein with overexpression of EcSOD also diminishes the secreted isoform of VEGF protein that is present extracellularly in the tissue microenvironment.

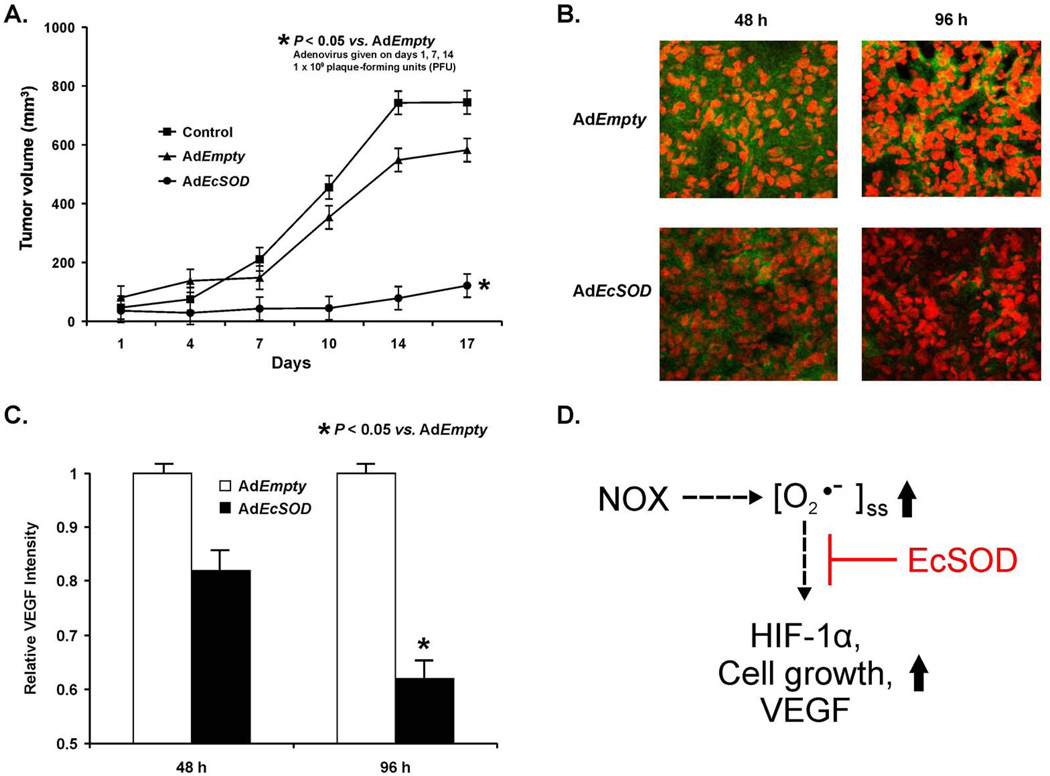

EcSOD inhibits tumor growth and VEGF expression in vivo

Because EcSOD inhibits hypoxic growth of pancreatic cancer cells, which is accompanied by suppression of HIF-1α protein accumulation and decrease in its downstream target VEGF’s expression, we wanted to determine if EcSOD could also modulate tumor growth in vivo and affect in vivo VEGF expression. When compared to the Control and AdEmpty groups of mice, the mice treated with intratumoral injections of AdEcSOD showed slower tumor growth (Figure 7A). For example on day 17 after the start of treatment, the Control and the AdEmpty group had mean tumor volumes of 745 mm3 and 582 mm3 respectively, while the AdEcSOD group had a mean tumor volume of 215 mm3 (p < 0.05 vs. AdEmpty). The mixed linear regression analysis of the tumor growth curves demonstrated that the rate of growth differed significantly between the groups (p < 0.0001). Pairwise group comparisons were carried out to identify where the group differences occurred. Significant differences were observed for Control vs. AdEmpty (p < 0.05), Control vs. AdEcSOD (P < 0.01), and AdEmpty vs. AdEcSOD (p < 0.01).

Figure 7. EcSOD overexpression inhibits tumor growth and VEGF expression in vivo.

A. AdEcSOD injections decreased MIA PaCa-2 tumor growth in nude mice. The AdEcSOD group had significantly slower tumor growth when compared to the Control and AdEmpty (p < 0.01, n = 5–8/group). On day-17 there was a 6-fold decrease in tumor growth in animals receiving the AdEcSOD vector when compared to Controls and a 4.5-fold decrease in tumor growth when compared to treatment with the AdEmpty vector.

B. AdEcSOD intratumoral injections decreased VEGF staining. Tumor specimens were harvested from AdEmpty treated mice and from mice treated with AdEcSOD at 48 and 96 h after treatment.

C. Relative intensities of VEGF were quantitated using Image J analysis demonstrating decreased VEGF staining 96 h after AdEcSOD injections. Mean ± SEM, n = 3, p < 0.05 vs. AdEmpty.

D. Our working model on how the O2•− produced by NOX2 in pancreatic cancer cells could regulate pancreatic cancer cell growth. Activation of NOX2 leads to an increase in the steady-state level of O2•−. This increase in O2•− leads to an increase in the accumulation of HIF-1α and an increase in associated downstream events, e.g. VEGF secretion and cell growth. The scavenging of extracellular O2•− by EcSOD inhibits the accumulation of HIF-1α accumulation and these events.

In separate experiments, mice were injected with MIA PaCa-2 cells or with clone #13 that stably overexpresses the EcSOD gene (Figure 3). Tumor size was measured every week for four weeks. In mice injected with MIA PaCa-2 cells, 100% of the mice developed tumors while only 25% of mice developed tumors when injected with cells overexpressing EcSOD.

We wanted to determine the effect of EcSOD-induced inhibition of in vivo growth on VEGF. In separate groups of animals, immunohistochemistry analysis demonstrated decreases in VEGF staining in mice treated with the AdEcSOD vector at 48 and 96 h when compared to tumors from mice treated with the AdEmpty vector (Figure 7B). When quantified, there were significantly lower levels of VEGF in the AdEcSOD group compared to AdEmpty controls at 96 h (Figure 7C). In addition to decreased VEGF levels, there was a similar decrease in microvessel growth as demonstrated by CD31 staining in tumor sections treated with AdEcSOD compared to those treated with AdEmpty (Supplemental Figure 7). Taken together, these results suggest that inhibition of in vivo pancreatic tumor growth by EcSOD is also accompanied by decreased VEGF expression and microvessel growth.

DISCUSSION

ROS, including O2•−, can play a role in altering HIF-1α signaling [6, 7],. Wheeler et al. demonstrated that EcSOD did not affect growth rates of melanoma cells in vitro, while systemic administration of an adenoviral construct containing the EcSOD gene inhibited growth of melanoma tumors in vivo [21]. In addition, VEGF expression was also significantly lower in AdEcSOD infected mice, as well as CD31 expression and blood vessel density. Our study also supports the hypothesis that EcSOD can inhibit in vivo tumor growth, and this is associated with suppression of VEGF expression. However, we also demonstrate that EcSOD inhibited hypoxic in vitro cell growth and clonogenic survival in pancreatic cancer cell lines. Additionally, we have shown an inverse correlation with EcSOD and HIF-1α when EcSOD is either transiently or stably overexpressed in human pancreatic cancer cells.

Wang and colleagues have previously shown that overexpression of manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSOD), the mitochondrial enzyme that scavenges O2•−, can prevent the stabilization of HIF-1α in hypoxic conditions [6]. In contrast to our findings with EcSOD, they demonstrated that the MnSOD-induced suppression was biphasic in their in vitro cell model. When MnSOD was at low levels of activity, HIF-1α accumulated in hypoxia. At moderate levels of MnSOD activity, HIF-1α accumulation was blocked and at high levels of MnSOD accumulation of HIF-1α was again observed. They also demonstrated that the re-stabilization of HIF-1α observed in high levels of MnSOD overexpression was due to H2O2, most likely produced by MnSOD. Our current study also demonstrates that scavenging O2•− suppresses HIF-1α. However, our study reveals a linear inverse relationship between EcSOD and HIF-1α, unlike the biphasic effect of MnSOD on HIF-1α. Additionally, when GPx is overexpressed with EcSOD, there is no reversal of suppressed HIF-1α, suggesting that O2•− and not H2O2 is essential in the stabilization of HIF-1α in pancreatic cancer. Further studies into the mechanism of MnSOD-induced suppression of HIF-1α demonstrated that removal of O2•− using pharmacological doses of spin traps or O2•− scavengers resulted in decreased HIF-1α [7]. However, the spin traps were not significantly toxic to the breast cancer cells used in the hypoxic conditions in these studies. It is likely that mechanisms of oxygen sensing and signaling during hypoxia are associated with mitochondrial ROS generation and may involve different pathways in different cell types [6, 29].

The biphasic effect observed with different levels of MnSOD on the accumulation of HIF-1α [6] compared with the inverse linear effect we observed with EcSOD is readily explained by consideration of the different sources of O2•−. Superoxide is generated both intra- and extracellularly through multiple pathways. In mitochondria, a major source of O2•− is the reaction of coenzyme Q semiquinone (CoQ•−) with dioxygen to form O2•−. This is a reversible reaction. Thus, an increase in MnSOD in the mitochondria will lower the steady-state level of O2•−, but will increase the flux of H2O230. High levels of O2•− facilitate accumulation of HIF-1α; as MnSOD is increased, the steady-state level of O2•− will decrease, resulting in a decrease in the accumulation of HIF-1α. Because of the nature of the source of O2•−, as MnSOD increases in the mitochondria the level of H2O2 will increase. High levels of H2O2 can also lead to accumulation of HIF-1α, thus the observed biphasic effect. However, the source of the extracellular O2•− being acted on by EcSOD is most likely an NADPH oxidase (NOX) at the cell surface [23]. The production of O2•− by the family of NOX enzymes is not a reversible reaction. Thus, an increase in EcSOD activity will decrease the steady-state level O2•−, but there will be no change in the level of H2O2, thus the linear inverse relationship observed with changes in the level of EcSOD.

Previous studies have demonstrated that the production of superoxide by endosomal NADPH oxidase activates transcription factors [31]. Unlike H2O2, membrane structures are relatively impermeable to superoxide; however, NOX-active endosomes contain anion channels capable of facilitating the movement of superoxide across cell membranes. SOD has been found to be recruited to the surface of superoxide-producing endosomes. Thus, superoxide is produced either outside the cell when the relevant NOX resides in the plasma membrane or in the endosomal lumen when the NOX complex is in an intracellular compartment [32]. This may explain why both EcSOD and the adenoviral vector that expresses EcSOD with deletion of its heparin binding domain, AdEcSODΔHBD inhibit HIF-1α. Hawkins et al. suggested that extracellular production of superoxide by NOX may influence cell signaling through the regulated uptake of superoxide at the plasma membrane and this similar regulation occurs at the level of the endosome [33].

In pancreatic cancer cells, oxygen sensing and signaling during hypoxia may be associated with non-mitochondrial ROS generation. Our current study demonstrates that EcSOD modulates HIF-1α signaling and may be even more effective than MnSOD in inhibiting pancreatic cancer cell growth since this isoform targets the tumor’s extracellular space [12]. In pancreatic cancer, non-mitochondrial production of O2•− may influence downstream propagation of mitogenic signaling. It is hypothesized that ras activates the NADPH oxidase system to produce O2•−, leading to cell proliferation [34]. This increased production of ROS may lead to an increased availability of O2•− to interact with and stabilize HIF-1α [6, 35], allowing this transcription or to be transported into the nucleus and promote tumor growth.

In our current study we have demonstrated that EcSOD inhibits pancreatic cancer cell growth in cell culture and in an animal model. Increasing levels of EcSOD correlated with decreasing HIF-1α and VEGF, suggesting that EcSOD-induced inhibition of tumorigenesis is associated with its modulation of HIF-1α signaling and subsequent disruption in angiogenesis. This evidence suggests that antioxidant-induced changes to the redox status of cells and tissues, specifically by EcSOD, can modulate cell proliferation (Figure 7D). Our qPCR results show suppression of VEGF-A mRNA expression in stable clones expressing EcSOD when compared to wild type cells; this suggests there is a threshold level of EcSOD whereupon EcSOD can inhibit VEGF-A mRNA expression. Forsythe et al. showed a dose-dependent decrease in VEGF expression with transfection of a dominant-negative form of HIF-1α [36], implying that EcSOD’s decrease in HIF-1α levels would subsequently lead to a dose-dependent decrease in VEGF protein. However, our study demonstrates that when HIF-1α falls beneath a certain threshold level, there is a complete blockage of VEGF expression and protein secretion.

Our results affirm prior studies demonstrating that HIF-1α is an important transcription factor in promoting angiogenesis, tumorigenicity, and metastases in the hypoxic tumor microenvironment and that EcSOD may modulate angiogenesis through HIF-1α. Since intratumoral hypoxia and increased HIF-1α levels have correlated with more aggressive tumor growth and spontaneous metastases in xenograft models [37] and with poorer clinical survival in pancreatic cancer, blocking HIF-1α accumulation with EcSOD, or pharmacological approaches that parallel the actions of EcSOD, could provide an important new therapeutic approach in pancreatic cancer.

Supplementary Material

Adenoviral transduction of EcSOD inhibits hypoxic AsPC-1 cell growth (A) and clonogenic survival (B).

EcSOD decreases HIF-1α accumulation in AsPC-1 cells.

HIF-1α expression is transient. MIA PaCa-2 cells incubated at 4% have an increase in HIF-1α. When cells are incubated in 4% and then 21%, HIF-1α protein levels return to baseline. Treatment with CoCl2 is used as a positive control.

Optimal HIF-1α response is at 4%.

AdEcSODΔHBD inhibits clonogenic survival.

Transient EcSOD overexpression suppressed VEGF protein secretion.

Intratumoral injections of AdEcSOD decreases CD31 expression and microvessel growth.

Highlights.

Extracellular SOD (EcSOD) modulates levels of HIF-1α in human pancreatic cancer cells.

EcSOD modulated vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF).

Increased EcSOD gene expression via (AdEcSOD) suppressed tumor growth in a murine model of pancreatic cancer.

Acknowledgments

Supported by NIH grants CA166800, GM073929, CA078586, CA148062, CA11365, the Susan L. Bader Foundation of Hope, and a Merit Review grant from the Medical Research Service, Department of Veterans Affairs 1I01BX001318-01A2.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kaelin WG, Jr, Ratcliffe PJ. Oxygen sensing by metazoans: the central role of the HIF hydroxylase pathway. Mol. Cell. 2008;30:393–402. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sun HC, Qiu ZJ, Liu J, Sun J, Jiang T, Huang KJ, Yao M, Huang C. Expression of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha and associated proteins in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and their impact on prognosis. Int J Oncol. 2007;30:1359–1367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoffmann AC, Mori R, Vallbohmer D, Brabender J, Klein E, Drebber U, Baldus SE, Cooc J, Azuma M, Metzger R, Hoelscher AH, Danenberg KD, Prenzel KL, Danenberg PV. High expression of HIF1α is a predictor of clinical outcome in patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas and correlated to PDGFA, VEGF, and bFGF. Neoplasia. 2008;10:674–679. doi: 10.1593/neo.08292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shibaji T, Nagao M, Ikeda N, Kanehiro H, Hisanaga M, Ko S, Fukumoto A, Nakajima Y. Prognostic significance of HIF-1 alpha overexpression in human pancreatic cancer. Anticancer Res. 2003;23:4721–4727. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Büchler P, Reber HA, Büchler M, Shrinkante S, Büchler MW, Friess H, Semenza GL, Hines OJ. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 regulates vascular endothelial growth factor expression in human pancreatic cancer. Pancreas. 2003;26:56–64. doi: 10.1097/00006676-200301000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang M, Kirk JS, Venkataraman S, Domann FE, Zhang HJ, Schafer FQ, Flanagan SW, Weydert CJ, Spitz DR, Buettner GR, Oberley LW. Manganese superoxide dismutase suppresses hypoxic induction of hypoxia-inducible factor-alpha and vascular endothelial growth factor. Oncogene. 2005;24:8154–8166. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaewpila S, Venkataraman S, Buettner GR, Oberley LW. Manganese superoxide dismutase modulates hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha induction via superoxide. Cancer Res. 2008;68:2781–2788. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chandel NS, McClintock DS, Feliciano CE, Wood TM, Melendez JA, Rodriguez AM, Schumacker PT. Reactive oxygen species generated at mitochondrial complex III stabilize hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha during hypoxia: a mechanism of O2 sensing. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:25130–25138. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001914200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Park JH, Kim TY, Jong HS, Kim TY, Chun YS, Park JW, Lee CT, Jung HC, Kim NK, Bang YJ. Gastric epithelial reactive oxygen species prevent normoxic degradation of hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha in gastric cancer cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:433–440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schroedl C, McClintock DS, Budinger GR, Chandel NS. Hypoxic but not anoxic stabilization of HIF-1alpha requires mitochondrial reactive oxygen species. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2002;283:L922–L931. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00014.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jabbari N, Cullen JJ. The Role of Antioxidant Enzymes in the Growth of Pancreatic Carcinoma. Curr Cancer Ther Rev. 2007;3:61–65. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adachi T, Kodera T, Ohta H, Hayashi K, Hirano K. The heparin binding site of human extracellular-superoxide dismutase. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1992;297:155–161. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(92)90654-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zelko IN, Mariani TJ, Folz RJ. Superoxide dismutase multigene family: a comparison of the CuZn-SOD (SOD1), Mn-SOD (SOD2), and EC-SOD (SOD3) gene structures, evolution, and expression. Free Radic Biol Med. 2002;33:337–349. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)00905-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Teoh ML, Sun W, Smith BJ, Oberley LW, Cullen JJ. Modulation of reactive oxygen species in pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:7441–7450. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Qian J, Niu J, Li M, Chiao PJ, Tsao M-S. In vitro modeling of human pancreatic duct epithelial cell transformation defines gene expression changes induced by K-ras oncogenic activation in pancreatic carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 2005;65:5045–5053. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peterson JR, Burmeister MA, Tian X, Zhou Y, Guruju MR, Stupinski JA, Sharma RV, Davisson RL. Genetic silencing of Nox2 and Nox4 reveals differential roles of these NADPH Oxidase homologues in the vasopressor and dispogenic effects of brain angiotensin II. Hypertension. 2009;54:1106–1114. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.140087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beauchamp C, Fridovich I. Superoxide dismutase: improved assays and an assay applicable to acrylamide gels. Anal Biochem. 1971;44:276–287. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(71)90370-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spitz DR, Oberley LW. An assay for superoxide dismutase activity in mammalian tissue homogenates. Anal Biochem. 1989;179:8–18. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(89)90192-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peskin AV, Winterbourn CC. A microtiter plate assay for superoxide dismutase using a water-soluble tetrazolium salt (WST-1) Clin Chim Acta. 2000;293:157–166. doi: 10.1016/s0009-8981(99)00246-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tomayko MM, Reynolds CP. Determination of subcutaneous tumor size in athymic (nude) mice. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1989;24:148–154. doi: 10.1007/BF00300234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wheeler MD, Smutney OM, Samulski RJ. Secretion of extracellular superoxide dismutase from muscle transduced with recombinant adenovirus inhibits the growth of B16 melanomas in mice. Mol Cancer Res. 2003;1:871–881. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marklund SL. Human copper-containing superoxide dismutase of high molecular weight. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1982;79:7634–7638. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.24.7634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Du J, Nelson ES, Simons AL, Olney KE, Moser JC, Schrock HE, Wagner BA, Buettner GR, Smith BJ, Teoh ML, Tsao MS, Cullen JJ. Regulation of pancreatic cancer growth by superoxide. Mol Carcinog. 2013;52:555–567. doi: 10.1002/mc.21891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu YV, Baek JH, Zhang H, Diez R, Cole RN, Semenza GL. RACK1 competes with HSP90 for binding to HIF-1alpha and is required for O(2)-independent and HSP90 inhibitor-induced degradation of HIF-1alpha. Mol Cell. 2007;25:207–217. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brown LF, Detmar M, Claffey K, Nagy JA, Feng D, Dvorak AM, Dvorak HF. Vascular permeability factor/vascular endothelial growth factor: a multifunctional angiogenic cytokine. EXS. 1997;79:233–269. doi: 10.1007/978-3-0348-9006-9_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brown LF, Detmar M, Claffey K, Nagy JA, Feng D, Dvorak AM, Dvorak HF. Vascular permeability factor/vascular endothelial growth factor induces lymphangiogenesis as well as angiogenesis. J Exp Med. 2002;196:1497–1506. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Choi KS, Bae MK, Jeong JW, Moon HE, Kim KW. Hypoxia-induced angiogenesis during carcinogenesis. J Biochem Mol Biol. 2003;36:120–127. doi: 10.5483/bmbrep.2003.36.1.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dvorak HF, Detmar M, Claffey KP, Nagy JA, van de Water L, Senger DR. Vascular permeability factor/vascular endothelial growth factor: an important mediator of angiogenesis in malignancy and inflammation. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 1995;107:233–235. doi: 10.1159/000236988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brunelle JK, Bell EL, Quesada NM, Vercauteren K, Tiranti V, Zeviani M, Scarpulla RC, Chandel NS. Oxygen sensing requires mitochondrial ROS but not oxidative phosphorylation. Cell Metab. 2005;1:409–414. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Buettner GR, Ng CF, Wang M, Rodgers VG, Schafer FQ. A new paradigm: manganese superoxide dismutase influences the production of H2O2 in cells and thereby their biological state. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2006;41:1338–1350. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mumbengegwi DR, Li Q, Li C, Bear CE, Engelhardt JF. Evidence for a superoxide permeability pathway in endosomal membranes. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:3700–3712. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02038-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lassegue B, Clempus RE. Vascular NAD(P)H oxidase: specific features, expression and regulation. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2003;285:R277–R297. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00758.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hawkins BJ, Madesh M, Kirkpatrick CJ, Fisher AB. Superoxide flux in endothelial cells via the chloride channel-3 mediates intracellular signaling. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:2002–2012. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-09-0830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vaquero EC, Edderkaoui M, Pandol SJ, Gukovsky I, Gukovskaya AS. Reactive oxygen species produced by NAD(P)H oxidase inhibit apoptosis in pancreatic cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:34643–34654. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400078200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Comito G, Calvani M, Giannoni E, Bianchini F, Calorini L, Torre E, Migliore C, Giordano S, Chiarugi P. HIF-1alpha stabilization by mitochondrial ROS promotes Met-dependent invasive growth and vasculogenic mimicry in melanoma cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;51:893–904. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.05.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Forsythe JA, Jiang BH, Iyer NV, Agani F, Leung SW, Koos RD, Semenza GL. Activation of vascular endothelial growth factor gene transcription by hypoxia-inducible factor 1. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:4604–4613. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.9.4604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chang Q, Jurisica I, Do T, Hedley DW. Hypoxia predicts aggressive growth and spontaneous metastasis formation from orthotopically grown primary xenografts of human pancreatic cancer. Cancer Res. 2011;71:3110–3120. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-4049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Adenoviral transduction of EcSOD inhibits hypoxic AsPC-1 cell growth (A) and clonogenic survival (B).

EcSOD decreases HIF-1α accumulation in AsPC-1 cells.

HIF-1α expression is transient. MIA PaCa-2 cells incubated at 4% have an increase in HIF-1α. When cells are incubated in 4% and then 21%, HIF-1α protein levels return to baseline. Treatment with CoCl2 is used as a positive control.

Optimal HIF-1α response is at 4%.

AdEcSODΔHBD inhibits clonogenic survival.

Transient EcSOD overexpression suppressed VEGF protein secretion.

Intratumoral injections of AdEcSOD decreases CD31 expression and microvessel growth.