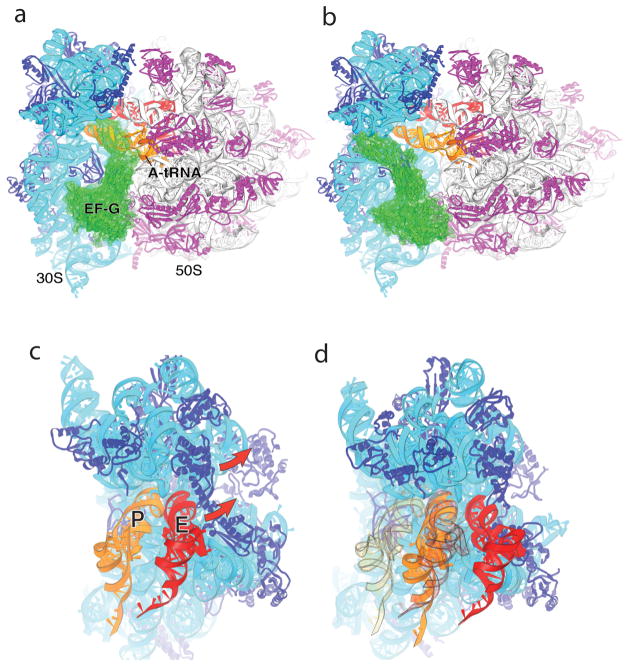

Fig. 6. Implications for EF-G and translocation.

(a) Observed orientation of EF-G (green) bound to the classical-state 70S ribosome·EF-G complex [56], in which tRNA has been modeled into the A site; note the severe steric clash between domain IV of EF-G and A-site tRNA. (b) Orientation of EF-G in the classical-state ribosome, but with its domain I docked on the 50S subunit in the same orientation as observed for RF3·GDPNP in the E. coli structure [43]. Note the absence of steric clash with A-site tRNA or the ribosome. (c,d) P-site ASL contacts in the 30S subunit head are displaced by 23 Å in the RF3 complex, relative to their position in the classical-state complex. Docking of P-site (orange) and E-site (red) tRNAs on the (c) classical-state RF2 and (d) rotated RF3 structures illustrates that the combined 30S head and body rotations seen in the E. coli RF3 structure are sufficient to translocate an ASL from the 30S P site to the E site, while allowing passage of the ASL of P-site tRNA to the E site without clash with the ribosome. The views in (c) and (d) are shown in exactly the same orientation relative to the 50S subunit. In (d), the initial positions of the P- and E-site tRNAs as in (c) are shown in transparent orange and red, respectively. From ref. [43].