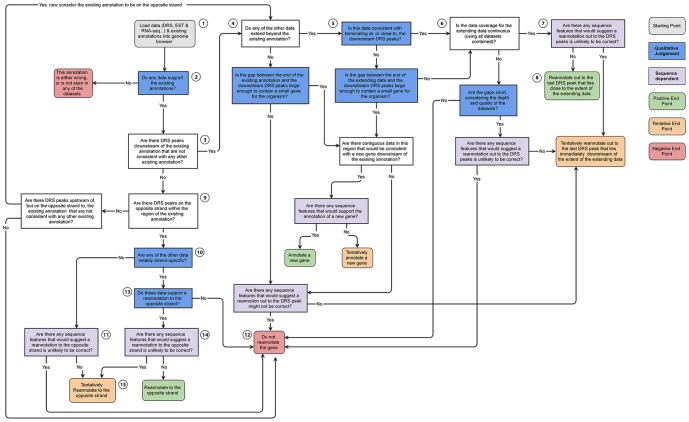

Figure 10. Reannotation flow diagram.

This flow diagram represents a distillation of the key aspects of the manual re-annotation process used for the examples presented here. Starting with loading the data into a genome browser (grey box, rounded corners), the process is a complex decision tree with several key stages that require judgement, experience and familiarity with the data in addition to quantitative information (blue boxes). This dependence on qualitative judgements makes this process extreme difficult to capture computationally (in addition to the fact that the process would necessarily change if used with different datasets, species, etc), underscoring the importance of manual annotation. Paths through the decision tree end in one of eight possible end-points; three ‘positive’ re-annotation endpoints (green boxes, rounded corners), three ‘tentative’ re-annotation endpoints (orange boxes, rounded corners) and two ‘negative’ no re-annotation endpoints. Here we briefly look at the path through the decision tree for two of the simpler examples presented earlier in this work: Example Path 1: BMPR1A (Section 1, Figure 1 ) Starting with loading the data for BMPR1A (1), the EST, cDNA and RNA-seq support the existing annotation intron/exon structure (2), DRS peaks exist downstream (3), RNA-seq and EST data extend beyond the existing annotation (4), the EST and RNA-seq data terminate almost exactly coincident with the strongest downstream DRS peak (5), taken together the RNA-seq and EST data have continuous coverage over the proposed extension (6), there are no clear sequence features (stop codon or internal priming signatures that strongly suggest the re-annotation would be incorrect (7), we propose a clear re-annotation of the gene (8). Example path 2: AT1G68945 (Section 1, Figure 5 ) Starting with loading the data for AT1G68945 (1), the EST, cDNA and RNA-seq support the existing annotation intron/exon structure (2), DRS peaks do not exist downstream (3), DRS peaks do exist on the opposite strand but within the existing annotation (9) the EST data are stranded, however they strand association is unreliable (10), there are sequence features (in this case, numerous stop codons in multiple frames (11), the data, sequence features and existing annotation are inconsistent. We cannot re-annotate the gene without more evidence.(12). In this case, further evidence in the form of strand-specific RNA-seq data from the Ecker Lab [35] would, if included, allow us to follow the path 1,2,3,9,10,13,14,15 resulting in a tentative re-annotation to the opposite strand, despite the apparent presence of stop codons.