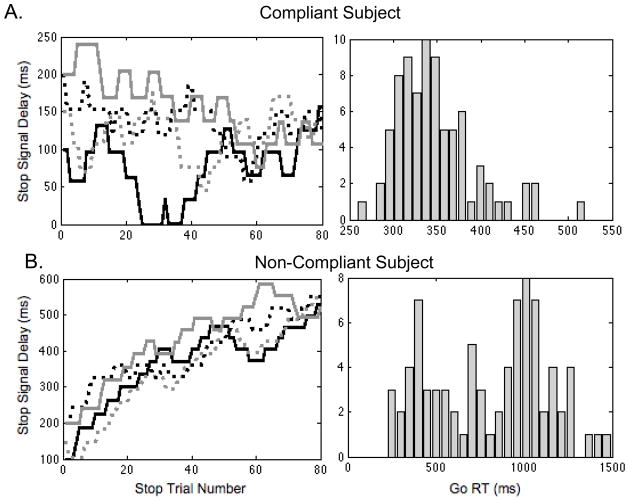

Figure 1.

Interpretations of performance differ for compliant (A) and non-compliant (B) subjects on the SSD tracking procedure (Experiment 1). On the left, we display the stop-signal delay (SSD) values as a function of stop trial number. Each line represents one of four staircases with different starting values. On a given stop-signal trial, the SSD is chosen from one of the four staircases. If inhibition is successful, the SSD for that staircase will be increased by 50ms and if inhibition is unsuccessful and a response is made, the SSD will be decreased by 50ms. Ideally, the four staircases will converge on the SSD value that results in 50% stopping accuracy. On the right, we display the go RT distributions from the tracking block. (A) The compliant subject consistently responded fast throughout the experiment, resulting in a typical choice RT distribution that is unimodal and slightly positively skewed (right). The four staircases (left) converge and oscillate around SSD = 125ms. (B) In contrast, the staircases for the noncompliant subject (left) steadily increase throughout the tracking block, suggesting the subject increasingly slowed responses in order to avoid responding on stop trials. The bimodal distribution of dramatically lengthened RTs (right) confirms this hypothesis and demonstrates a type of noncompliant behavior that can compromise the utility of an SSD tracking procedure.