Abstract

Nicotinic adenine acid dinucleotide phosphate (NAADP) is one of the most potent endogenous Ca2+ mobilizing messengers. NAADP mobilizes Ca2+ from an acidic lysosome-related store, which can be subsequently amplified into global Ca2+ waves by calcium-induced calcium release (CICR) from ER/SR via Ins(1,4,5)P3 receptors or ryanodine receptors. A body of evidence indicates that 2 pore channel 2 (TPC2), a new member of the superfamily of voltage-gated ion channels containing 12 putative transmembrane segments, is the long sought after NAADP receptor. Activation of NAADP/TPC2/Ca2+ signaling inhibits the fusion between autophagosome and lysosome by alkalizing the lysosomal pH, thereby arresting autophagic flux. In addition, TPC2 is downregulated during neural differentiation of mouse embryonic stem (ES) cells, and TPC2 downregulation actually facilitates the neural lineage entry of ES cells. Here we propose the mechanism underlying how NAADP-induced Ca2+ release increases lysosomal pH and discuss the role of TPC2 in neural differentiation of mouse ES cells.

Keywords: Autophagy, lysosome, NAADP, Ca2+, pH, TPC2, Rab7

Intracellular Ca2+ mobilization plays an important role in a wide variety of cellular processes, and multiple second messengers are responsible for mediating intracellular Ca2+ changes.1, 2 Nicotinic adenine acid dinucleotide phosphate (NAADP) is one of the most potent endogenous Ca2+ mobilizing messengers. NAADP mobilizes Ca2+ from acidic lysosome-related stores, which can be subsequently amplified by calcium-induced calcium release (CICR) from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). It has been shown that many extracellular stimuli can induce NAADP production leading to Ca2+ mobilization, which establishes NAADP as a second messenger.3 Recently, 2 pore channels (TPCs) have been identified as a novel family of NAADP-gated calcium release channels in endolysosomes. The TPC2 forms NAADP receptors that release Ca2+ from lysosomes, which can subsequently trigger global Ca2+ signals via the ER.4-8 Yet several recent papers suggest that NAADP binds to an accessory protein to activate TPC2.9,10 The Ca2+-signaling pathway mediated by NAADP is ubiquitous and the functions it regulates are equally diverse, including fertilization,11,12 receptor activation in lymphocytes,13 insulin secretion in pancreatic islets,14 hormonal signaling in pancreatic acinar cells,15 platelet activation,16 cardiac muscle contraction,17 blood pressure control,18 neurotransmitter release,19 neurite outgrowth,20 and neuronal differentiation.21 Therefore, decoding the molecular mechanisms involved in this novel signaling pathway is important not only for scientific reasons but also has clinical relevance.

Autophagy, an evolutionarily conserved lysosomal degradation pathway, has been implicated in a wide variety of cellular processes, yet the underlying mechanisms remain poorly understood. Recent vigorous research efforts have led to the identification of the core molecular machinery for autophagy, powered by the discovery of 35 ATG genes via yeast genetics. However, even after extensive research, the regulation and mechanisms of autophagy induction, autophagosome formation and maturation, and autophagosomal-lysosomal fusion remain elusive in mammalian cells.22-27 Since the completion of autophagy depends on lysosomal activity, any defect in autophagosomal-lysosomal fusion can lead to the accumulation of autophagosomes, ultimately damaging cells or resulting in cell death. Despite that autophagosomal-lysosomal fusion is poorly understood, many popular autophagy modulators, e.g., bafilomycin and hydroxychloroquine, actually inhibit this process by targeting lysosomal activity. Hydroxychloroquine has even been applied in several human anticancer clinical trials. Yet most of these inhibitors either lack specificity or potency.28,29 Thus, in order to identify potent and specific modulators of autophagy for future human disease therapy, it is essential to fully understand the molecular mechanisms underlying this process.

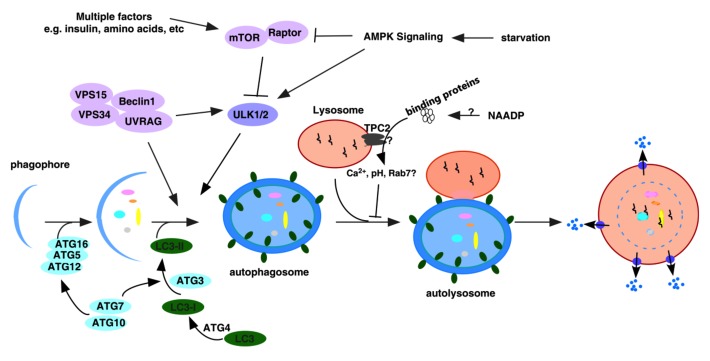

Intracellular Ca2+ has already been established as one of the regulators of autophagy induction, either positively or negatively depending upon the context of time, space, Ca2+ source, and cell state.30-32 Yet, the effects of Ca2+ on autophagosomal-lysosomal fusion have not been determined. Thus, we examined the role of the NAADP/TPC2/ Ca2+ signaling in this process in mammalian cells. We found that overexpression of a wildtype, not an inactive mutant, TPC2 in HeLa cells that lack detectable level of endogenous TPC2 protein inhibited autophagosomal-lysosomal fusion. Treatment of TPC2 overexpressing cells with a cell permeant-NAADP agonist, NAADP-AM, further inhibited fusion, whereas Ned-19, a NAADP antagonist, promoted fusion. Likewise, TPC2 knockdown in mouse embryonic stem (ES) cells promoted autophagosomal-lysosomal fusion during early neural differentiation. ATG5 knockdown abolished TPC2-induced accumulation of autophagosomes, but inhibiting mTOR activity had no effect on it. Instead, overexpression of TPC2 alkalinized lysosomal pH, and lysosomal re-acidification abolished TPC2-induced autophagosome accumulation (Fig. 1). Interestingly, TPC2 overexpression had no effect on general endosomal-lysosomal degradation but prevented the recruitment of Rab-7 to autophagosomes. Taken together, our data demonstrate that TPC2/NAADP/Ca2+ signaling alkalinizes lysosomal pH to suppress the later stage of autophagy progression (Fig. 2).7,8

Figure 1. TPC2 signaling inhibited autophagy by increasing lysosomal pH in HeLa cells. (A) TPC2 overexpression induced an increase of lysosomal pH in Hela cells as determined by microplate reader measurement of Lysosensor DND-189 stained cells. Extracellular acidification decreased lysosomal pH in both control and TPC2 overexpressing cells. (B) Extracellular acidification reversed the accumulation of LC3-II and p62 in TPC2 overexpressing HeLa cells. The densitometric analyses of LC3-II and p62 represent data from 2 independent experiments.

Figure 2. Schematic of the NAADP/TPC2/Ca2+ pathway-mediated inhibition of autophagosomal-lysosomal fusion in mammalian cells. NAADP, likely via accessory protein(s), activates TPC2 to trigger Ca2+ release from lysosomes. This is accompanied with lysosomal pH increase, which subsequently prevents the recruitment of Rab-7 to autophagosomes, thereby inhibiting the fusion between autophagosome and lysosome.

Upon withdrawal of self-renewal stimuli, mouse ES cells spontaneously enter neural lineages in monolayer adherent monoculture.33 Interestingly, the expression of TPC2 was significantly decreased in ES cells during their initial entry into neural progenitors, which was accompanied by the gradual induction of autophagy. TPC2 knockdown accelerated mouse ES cells entry into early neural lineages, whereas TPC2 overexpression in ES cells markedly inhibited it. We speculate that TPC2 downregulation during early neural differentiation of ES cells facilitates the fusion between autophagosome and lysosome, thereby enabling faster energy recycling to be utilized for target differentiation. On the other hand, TPC2 overexpression blocks the fusion to prevent energy recycling and inhibits neural differentiation. Taken together, our results established a physiological function of TPC2-mediated autophagy inhibition during early neural differentiation of ES cells.8

It has previously been reported that activation of NAADP/TPC2 signaling increased LC3-II levels,34,35 and downregulation of TPC2 by presenilin decreased it.36 Although these reports concluded that the increased LC3-II results from induction of autophagy by NAADP/TPC2 signaling, we clearly demonstrated that the increased LC3-II is actually due to the inhibition of autophagosomal-lysosomal fusion, not autophagy induction, by NAADP/TPC2 signaling (Fig. 2).7 Because of its diversified physiological roles, the efforts to generate NAADP analogs chemically or from the corresponding NADP analogs using ADP-ribosyl cyclase are already underway. Since NAADP antagonists accelerate autophagosomal-lysosomal fusion whereas NAADP agonists inhibit it, the development of potent and cell permeable NAADP agonists or antagonists in the near future should provide a novel approach to specifically manipulate autophagy.

Ca2+ has long been established as an essential ion for membrane fusion,37,38 and a local Ca2+ increase via extracellular Ca2+ influx is essential for exocytosis of synaptic vesicles, in which synaptogamin acts as Ca2+ sensor.39 Thus we originally expected that NAADP/TPC2-mediate Ca2+ release should facilitate autophagosomal-lysosomal fusion. However, whether local Ca2+ release from internal Ca2+ stores is required for intracellular membrane fusion events has actually not been determined. NAADP can induce Ca2+ release from lysosomes, and we found that NAADP treatment actually inhibited autophagosomal-lysosomal fusion. These data argue that local Ca2+ release from lysosomes does not facilitate autophagosomal-lysosomal fusion. On the other hand, BAPTA-AM, a Ca2+ chelator, quickly blocked autophagosomal-lysosomal fusion, indicating that Ca2+ itself is required for this process (Fig. 3). Therefore, these data suggest that the basal cytosolic Ca2+ level, not a local Ca2+ increase, is permissive for autophagosomal-lysosomal fusion, which is supported by the fact that membrane fusion can be reconstituted in an in vitro system that only contains the basal Ca2+ concentration.40,41 Notably, the accumulation of both LC3-II and p62 induced by BAPTA-AM was transient (Fig. 3), suggesting that Ca2+ differentially regulates autophagy at different levels. Along this line, numerous studies indeed have already documented that intracellular Ca2+ can differentially modulate autophagy within the context of time, space, Ca2+ source, and cell status.31,42

Figure 3. The effects of BAPTA-AM on the accumulation of LC3-II and p62 in control and TPC2 overexpressing HeLa cells. Cell lysates were harvested at indicated time points after BAPTA-AM (20 μM) treatment in both control and TPC2 overexpressing HeLa cells, and analyzed for expression of LC3, p62, and GAPDH by western blot analyses. The densitometric analyses of LC3-II and p62 represent data from 2 independent experiments.

Importantly, our findings added TPC2 to a handful of transporters, including V-ATPase and chloride channels, which can modulate lysosomal pH. V-ATPase, a multi-subunit protein complex, pumps protons into the lysosomal lumen against an electrochemical gradient at the expense of ATP hydrolysis to generate the acidic milieu in lysosomes. 43The positive lysosomal membrane potential, created by the influx of protons, reciprocally, could prevent the V-ATPase from continuing to pump protons. Obviously, efflux of cations, or influx of anions, or both, is needed to maintain the balance of acidic pH and membrane potential inside lysosomes.44 Along this line, Cl- influx has already been proposed to dissipate the restrictive electrical gradient for maintaining acidic lysosomal pH.45,46 Yet, whether Cl- is the main counter ion remains to be determined, let alone the identity of Cl- transporters in lysosomes.43 Ca2+, whose concentration in lysosomes is high,47,48 is another potential counter ion, yet the channels for Ca2+ release or refilling in lysosomes also remain elusive. Interestingly, NAADP induced Ca2+ release via TPC2 from lysosomes is accompanied by an increased lysosomal pH, indicating proton efflux with Ca2+ release. These data suggested that Ca2+ is not the counter ion for maintaining acidic pH in lysosomes.

How NAADP/TPC2-induced Ca2+ release alkalizes lysosomal pH remains mysterious. One explanation is that Ca2+ and protons are simultaneously released from lysosomes via TPC2, or TPC1, or other unidentified channels upon NAADP treatment (Fig. 4A). Yet, whether TPCs are proton permeable and the identity of other proton channels remain to be determined. On the other hand, lysosomal alkalization might be the result of proton efflux accompanied by Ca2+ refilling after its release from lysosomes. A putative vacuolar Ca2+/H+ counter-exchanger,49 like the one in yeast or plant, can be activated to refill the lysosomal Ca2+ pools at the expense of proton efflux upon Ca2+ release from lysosomes via TPC2 (Fig. 4B). Alternatively, an unidentified lysosomal P-type Ca2+ ATPase,48 similar to SERCA in ER, can also refill Ca2+ in exchange of luminal protons at the expense of ATP hydrolysis (Fig. 4C). Another possible way for Ca2+ to enter lysosomes is the coupling of several lysosomal proton-cation counter-transporters, such as the sequential action of Ca2+/Na+ exchangers and Na+/H+ exchangers (Fig. 4D). Unfortunately, except for the V-ATPase, ion channels or transporters responsible for the creation of the unique ionic environment inside lysosomes have not been identified.49 We anticipate that an ongoing lysosomal proteomics study in the lab will help identify the respective transporters.

Figure 4. Models of NAADP/TPC2/Ca2+ signaling induced lysosomal alkalization in mammalian cells. (A) NAADP induces the release of Ca2+ and H+ from lysosomes via TPCs or an unknown channel. (B), (C), and (D) After Ca2+ release from lysosomes via TPC2, Ca2+ refilling via a putative Ca2+/H+ counter-exchanger (B), or a P-type Ca2+ pump (C), or the sequential coupling of several cation counter-exchangers, e.g., Ca2+/Na+ and Na+/H+ (D), could also lead to lysosomal alkalization.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Yue lab for advice on the manuscript. Our research is supported by the Research Grant Council (RGC) grants (HKU 782709M, HKU 785911M, HKU 769912M, and HKU 785213M).

References

- 1.Galione A, Churchill GC. Interactions between calcium release pathways: multiple messengers and multiple stores. Cell Calcium. 2002;32:343–54. doi: 10.1016/S0143416002001902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berridge MJ, Galione A. Cytosolic calcium oscillators. FASEB J. 1988;2:3074–82. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.2.15.2847949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guse AH, Lee HC. NAADP: a universal Ca2+ trigger. Sci Signal. 2008;1:re10. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.144re10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yi C, Ma M, Ran L, Zheng J, Tong J, Zhu J, Ma C, Sun Y, Zhang S, Feng W, et al. Function and molecular mechanism of acetylation in autophagy regulation. Science. 2012;336:474–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1216990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brailoiu E, Churamani D, Cai X, Schrlau MG, Brailoiu GC, Gao X, Hooper R, Boulware MJ, Dun NJ, Marchant JS, et al. Essential requirement for two-pore channel 1 in NAADP-mediated calcium signaling. J Cell Biol. 2009;186:201–9. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200904073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Calcraft PJ, Ruas M, Pan Z, Cheng X, Arredouani A, Hao X, Tang J, Rietdorf K, Teboul L, Chuang KT, et al. NAADP mobilizes calcium from acidic organelles through two-pore channels. Nature. 2009;459:596–600. doi: 10.1038/nature08030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lu Y, Hao BX, Graeff R, Wong CW, Wu WT, Yue J. Two pore channel 2 (TPC2) inhibits autophagosomal-lysosomal fusion by alkalinizing lysosomal pH. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:24247–63. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.484253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 8.Zhang ZH, Lu YY, Yue J. Two pore channel 2 differentially modulates neural differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells. PLoS One. 2013;8:e66077. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walseth TF, Lin-Moshier Y, Jain P, Ruas M, Parrington J, Galione A, Marchant JS, Slama JT. Photoaffinity labeling of high affinity nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NAADP)-binding proteins in sea urchin egg. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:2308–15. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.306563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin-Moshier Y, Walseth TF, Churamani D, Davidson SM, Slama JT, Hooper R, Brailoiu E, Patel S, Marchant JS. Photoaffinity labeling of nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NAADP) targets in mammalian cells. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:2296–307. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.305813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Churchill GC, O’Neill JS, Masgrau R, Patel S, Thomas JM, Genazzani AA, Galione A. Sperm deliver a new second messenger: NAADP. Curr Biol. 2003;13:125–8. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(03)00002-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moccia F, Lim D, Kyozuka K, Santella L. NAADP triggers the fertilization potential in starfish oocytes. Cell Calcium. 2004;36:515–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2004.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berg I, Potter BV, Mayr GW, Guse AH. Nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NAADP(+)) is an essential regulator of T-lymphocyte Ca(2+)-signaling. J Cell Biol. 2000;150:581–8. doi: 10.1083/jcb.150.3.581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Masgrau R, Churchill GC, Morgan AJ, Ashcroft SJ, Galione A. NAADP: a new second messenger for glucose-induced Ca2+ responses in clonal pancreatic beta cells. Curr Biol. 2003;13:247–51. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(03)00041-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yamasaki M, Masgrau R, Morgan AJ, Churchill GC, Patel S, Ashcroft SJ, Galione A. Organelle selection determines agonist-specific Ca2+ signals in pancreatic acinar and beta cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:7234–40. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311088200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.López JJ, Redondo PC, Salido GM, Pariente JA, Rosado JA. Two distinct Ca2+ compartments show differential sensitivity to thrombin, ADP and vasopressin in human platelets. Cell Signal. 2006;18:373–81. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2005.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Macgregor A, Yamasaki M, Rakovic S, Sanders L, Parkesh R, Churchill GC, Galione A, Terrar DA. NAADP controls cross-talk between distinct Ca2+ stores in the heart. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:15302–11. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611167200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brailoiu GC, Gurzu B, Gao X, Parkesh R, Aley PK, Trifa DI, Galione A, Dun NJ, Madesh M, Patel S, et al. Acidic NAADP-sensitive calcium stores in the endothelium: agonist-specific recruitment and role in regulating blood pressure. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:37133–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C110.169763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brailoiu E, Patel S, Dun NJ. Modulation of spontaneous transmitter release from the frog neuromuscular junction by interacting intracellular Ca(2+) stores: critical role for nicotinic acid-adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NAADP) Biochem J. 2003;373:313–8. doi: 10.1042/BJ20030472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brailoiu E, Hoard JL, Filipeanu CM, Brailoiu GC, Dun SL, Patel S, Dun NJ. Nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide phosphate potentiates neurite outgrowth. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:5646–50. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408746200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brailoiu E, Churamani D, Pandey V, Brailoiu GC, Tuluc F, Patel S, Dun NJ. Messenger-specific role for nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide phosphate in neuronal differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:15923–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602249200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang Z, Klionsky DJ. Eaten alive: a history of macroautophagy. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:814–22. doi: 10.1038/ncb0910-814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Janku F, McConkey DJ, Hong DS, Kurzrock R. Autophagy as a target for anticancer therapy. Nature reviews. Clin Oncol. 2011;8:528–39. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2011.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.White E. Deconvoluting the context-dependent role for autophagy in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:401–10. doi: 10.1038/nrc3262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eskelinen EL. Maturation of autophagic vacuoles in Mammalian cells. Autophagy. 2005;1:1–10. doi: 10.4161/auto.1.1.1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kroemer G, Jäättelä M. Lysosomes and autophagy in cell death control. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:886–97. doi: 10.1038/nrc1738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ravikumar B, Sarkar S, Davies JE, Futter M, Garcia-Arencibia M, Green-Thompson ZW, Jimenez-Sanchez M, Korolchuk VI, Lichtenberg M, Luo S, et al. Regulation of mammalian autophagy in physiology and pathophysiology. Physiol Rev. 2010;90:1383–435. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00030.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fleming A, Noda T, Yoshimori T, Rubinsztein DC. Chemical modulators of autophagy as biological probes and potential therapeutics. Nat Chem Biol. 2011;7:9–17. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baek KH, Park J, Shin I. Autophagy-regulating small molecules and their therapeutic applications. Chem Soc Rev. 2012;41:3245–63. doi: 10.1039/c2cs15328a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cárdenas C, Foskett JK. Mitochondrial Ca(2+) signals in autophagy. Cell Calcium. 2012;52:44–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Decuypere JP, Bultynck G, Parys JB. A dual role for Ca(2+) in autophagy regulation. Cell Calcium. 2011;50:242–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2011.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smaili SS, Pereira GJ, Costa MM, Rocha KK, Rodrigues L, do Carmo LG, Hirata H, Hsu YT. The role of calcium stores in apoptosis and autophagy. Curr Mol Med. 2013;13:252–65. doi: 10.2174/156652413804810772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ying QL, Stavridis M, Griffiths D, Li M, Smith A. Conversion of embryonic stem cells into neuroectodermal precursors in adherent monoculture. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21:183–6. doi: 10.1038/nbt780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gómez-Suaga P, Luzón-Toro B, Churamani D, Zhang L, Bloor-Young D, Patel S, Woodman PG, Churchill GC, Hilfiker S. Leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 regulates autophagy through a calcium-dependent pathway involving NAADP. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21:511–25. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pereira GJ, Hirata H, Fimia GM, do Carmo LG, Bincoletto C, Han SW, Stilhano RS, Ureshino RP, Bloor-Young D, Churchill G, et al. Nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NAADP) regulates autophagy in cultured astrocytes. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:27875–81. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C110.216580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Neely Kayala KM, Dickinson GD, Minassian A, Walls KC, Green KN, Laferla FM. Presenilin-null cells have altered two-pore calcium channel expression and lysosomal calcium: implications for lysosomal function. Brain Res. 2012;1489:8–16. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2012.10.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Burgoyne RD, Clague MJ. Calcium and calmodulin in membrane fusion. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003;1641:137–43. doi: 10.1016/S0167-4889(03)00089-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Piper RC, Luzio JP. CUPpling calcium to lysosomal biogenesis. Trends Cell Biol. 2004;14:471–3. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2004.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jahn R, Fasshauer D. Molecular machines governing exocytosis of synaptic vesicles. Nature. 2012;490:201–7. doi: 10.1038/nature11320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miller SG, Moore HP. Reconstitution of constitutive secretion using semi-intact cells: regulation by GTP but not calcium. J Cell Biol. 1991;112:39–54. doi: 10.1083/jcb.112.1.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mima J, Hickey CM, Xu H, Jun Y, Wickner W. Reconstituted membrane fusion requires regulatory lipids, SNAREs and synergistic SNARE chaperones. EMBO J. 2008;27:2031–42. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cárdenas C, Miller RA, Smith I, Bui T, Molgó J, Müller M, Vais H, Cheung KH, Yang J, Parker I, et al. Essential regulation of cell bioenergetics by constitutive InsP3 receptor Ca2+ transfer to mitochondria. Cell. 2010;142:270–83. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mindell JA. Lysosomal acidification mechanisms. Annu Rev Physiol. 2012;74:69–86. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-012110-142317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.DiCiccio JE, Steinberg BE. Lysosomal pH and analysis of the counter ion pathways that support acidification. J Gen Physiol. 2011;137:385–90. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201110596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Graves AR, Curran PK, Smith CL, Mindell JA. The Cl-/H+ antiporter ClC-7 is the primary chloride permeation pathway in lysosomes. Nature. 2008;453:788–92. doi: 10.1038/nature06907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Deriy LV, Gomez EA, Zhang G, Beacham DW, Hopson JA, Gallan AJ, Shevchenko PD, Bindokas VP, Nelson DJ. Disease-causing mutations in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator determine the functional responses of alveolar macrophages. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:35926–38. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.057372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Christensen KA, Myers JT, Swanson JA. pH-dependent regulation of lysosomal calcium in macrophages. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:599–607. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.3.599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Patel S, Docampo R. Acidic calcium stores open for business: expanding the potential for intracellular Ca2+ signaling. Trends Cell Biol. 2010;20:277–86. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2010.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Morgan AJ, Platt FM, Lloyd-Evans E, Galione A. Molecular mechanisms of endolysosomal Ca2+ signalling in health and disease. Biochem J. 2011;439:349–74. doi: 10.1042/BJ20110949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]