Abstract

Microbiota and host form a complex ‘super-organism’ in which symbiotic relationships confer benefits to the host in many key aspects of life. However, defects in the regulatory circuits of the host that control bacterial sensing and homeostasis, or alterations of the microbiome, through environmental changes (infection, diet or lifestyle), may disturb this symbiotic relationship and promote disease. Increasing evidence indicates a key role for the bacterial microbiota in carcinogenesis. In this Opinion article, we discuss links between the bacterial microbiota and cancer, with a particular focus on immune responses, dysbiosis, genotoxicity, metabolism and strategies to target the microbiome for cancer prevention.

Since the late nineteenth century, when Koch postulated that a pathogen must be isolated from the diseased subject, grown in pure culture and cause disease when reintroduced into a susceptible recipient1, research on microbial interactions with humans has focused on single pathogenic organisms. On the basis of these principles, we have witnessed tremendous progress in our understanding and in the treatment of infectious diseases over the past 100 years. Moreover, we have learned that chronic infections contribute to carcinogenesis with approximately 18% of the global cancer burden being directly attributable to infectious agents2,3. Many pathogens, particularly viruses, promote cancer through well-described genetic mechanisms4. Other pathogens, such as Helicobacter pylori and hepatitis C virus, promote the development of cancer through epithelial injury and inflammation, which — as postulated by Virchow5 150 years ago — contributes to carcinogenesis2,3,6. However, recent evidence suggests that human disease is attributable not only to single pathogens but also to global changes in our microbiome7,8. Our microbiome — often termed the “forgotten organ” (REF. 9) — contains a metagenome that exceeds our own genome by 100-fold (REFS 10,11) and exerts key functions that are relevant to human health12. Traditional culture-based methods capture only a small proportion, typically less than 30%, of our bacterial microbiota13. Culture-independent analysis using next-generation sequencing has closed this gap and has been essential in defining and understanding the bacterial microbiome and metagenome, and its key role in metabolism and inflammation12,14 — two factors that contribute to carcinogenesis in modern societies15,16. In this Opinion article, we discuss the possible roles of the bacterial microbiome in carcinogenesis, focusing on host–microbiota interactions and effector mechanisms. The contribution of viruses to carcinogenesis has been reviewed elsewhere4.

Cancer-modulating effects of microbiota

Microbiota and host have co-evolved into a complex ‘super-organism’, the intricate relationships of which benefit the host in many ways, such as through nutrition and metabolism12,14. However, this close relationship also carries risks for disease development, particularly when host regulatory pathways that guard homeostasis are perturbed. Of the microbial mass, 99% is within the gastrointestinal tract, and it exerts both local and long-distance effects. For this reason, the gastrointestinal microbiome not only has the greatest effect on overall health and metabolic status of all the microbiomes but it is also the best-investigated microbiome and serves as a model for understanding host–microbiota interactions and disease. Other organs with a well-characterized microbiome include the skin and the vagina14,17. The microbiome of each organ is distinct14, which suggests that effects on inflammation and carcinogenesis are likely to be organ specific. Moreover, there is an important and functionally relevant inter-individual variability of microbiomes14, which renders them a potential determinant of disease (including cancer) development. In addition, the microbial community and abundance vary in different locations within organs14,17. These differences might be an explanation for the occurrence of diseases, including cancer, in particular locations within an organ; for example, the higher rate of cancer in the large intestine — where microbial densities are much higher than in the small intestine9. In the gastrointestinal tract, the bacterial community also varies between luminal- and mucosa-associated communities18. Although many organs, for example, the liver, do not contain a known microbiome, they may be exposed to microorganism-associated molecular patterns (MAMPs) and bacterial metabolites through anatomical links with the gut19–22.

Studies in germ-free animals have revealed evidence for tumour-promoting effects of the microbiota in spontaneous, genetically-induced and carcinogen-induced cancers in various organs, including the skin, colon, liver, breast and lungs21,23–33 (TABLE 1). Similarly, depletion of the intestinal bacterial microbiota in mice, using antibiotics, reduces the development of cancer in the liver and the colon21,22,34–37, as does the eradication of specific pathogens in humans and in mice38–40 (TABLE 1). Although most of these studies show tumour-promoting effects of the bacterial microbiota, antitumour effects have also been observed. In the late nineteenth century antitumour effects were observed in patients with sarcomas, after bacterial infections or after the injection of heat-killed bacteria (termed Coley’s toxin)41,42. Subsequent studies implicated specific bacterial components, which were later identified as Toll-like receptor (TLR) agonists and NOD-like receptor (NLR) agonists, as being responsible for many of these antitumour effects; this led to the concept that potent activation of innate immunity may convert tumour tolerance into antitumour immune responses43–45. However, apart from life-threatening infections and TLR- and NLR-based therapeutic interventions44, the bacterial microbiota rarely triggers the degree of innate immune activation that is required for antitumour immune responses, and instead it often induces disease-promoting low-grade chronic inflammation. Indeed, there is increasing evidence from patients and animal models that shows relevant cancer-promoting effects of the microbiota in many organs, particularly in those that are exposed to the microbiota or to MAMPs (TABLE 1). However, mechanisms of microbiota-driven carcinogenesis substantially differ between organs (TABLE 2).

Table 1.

Evidence for tumour-promoting effects of the bacterial microbiota

| Cancer type | Disease or model | Findings | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Murine studies | |||

| Colorectal cancer | Germ-free rats and spontaneous carcinogenesis | Fewer tumours in germ-free rats | 23 |

| Germ-free rats and DMH-induced | Fewer tumours in germ-free rats | 25 | |

| Germ-free rats and AOM-induced | More tumours in germ-free rats | 28 | |

| Germ-free rats and MAM-GlcUA | Fewer tumours in germ-free rats | 28 | |

| Germ-free rats and AOM-induced | Fewer tumours in germ-free rats | 32 | |

| AOM in Il10−/− gnotobiotic mice | Fewer tumours in germ-free mice | 29 | |

| Germ-free ApcMin/+ mice | Fewer tumours in germ-free mice | 31 | |

| ApcMin/+ Cdx2–Cre mice treated with antibiotic cocktail | Fewer tumours in antibiotic-treated mice | 36 | |

| Nod1−/− mice treated with antibiotic cocktail | Fewer tumours in antibiotic-treated mice | 34 | |

| AOM plus DSS -treated mice treated with antibiotic cocktail | Fewer tumours in antibiotic-treated mice | 37 | |

| Wild-type microbiota transplanted into Nod2−/− mice | Fewer tumours after transplant | 78 | |

| Gastric cancer | Helicobacter pylori-infected gnotobiotic INS-GAS mice | Fewer tumours in germ-free mice | 30 |

| H. pylori-infected INS-GAS mice, treated with antibiotic | Fewer tumours in antibiotic-treated mice | 38 | |

| Liver cancer | DEN plus CCl4-treated germ-free mice | Fewer tumours in germ-free mice | 21 |

| DEN plus CCl4-treated mice, receiving antibiotic cocktail | Fewer tumours in antibiotic-treated mice | 21 | |

| DEN plus CCl4-treated mice, receiving rifaximin | Fewer tumours in rifaximin-treated mice | 21 | |

| DEN-treated rats, receiving neomycin | Fewer tumours in neomycin-treated rats | 35 | |

| DMBA and high-fat-diet-treated mice, receiving antibiotic cocktail | Fewer tumours in antibiotic-treated mice | 22 | |

| DMBA and high-fat-diet-treated mice, receiving vancomycin | Fewer tumours in vancomycin-treated mice | 22 | |

| Lung cancer | NHMI-treated germ-free rats |

|

24 |

| Breast cancer | DMAB-treated germ-free rats | Reduced tumours in germ-free rats | 26 |

| Human studies | |||

| Gastric cancer | H. pylori eradication by antibiotics | Reduced cancer in antibiotic-treated patients | 39,40 |

| Gastric MALT lymphoma | H. pylori eradication by antibiotics | Regression after eradication | 51 |

| Skin MALT lymphoma | Borrelia burgdorferi eradication by antibiotics | Regression after eradication | 53 |

| IPSID | Campylobacter jejuni eradication by antibiotics | Regression after eradication | 52 |

| Ocular adnexal lymphoma | Chlamydia psittaci eradication by doxycycline | Regression after eradication | 54 |

AOM, azoxymethane; Apc, adenomatous polyposis coli; CCl4, carbon tetrachloride; Cdx2, caudal type homeobox 2; DEN, diethylnitrosamine; DMAB, 3,2′-dimethyl- 4-aminobiphenyl hydrochloride; DMH, dimethylhydrazine; DSS, dextran sodium sulphate; Il10, interleukin-10; IPSID, immunoproliferative small intestinal disease; MALT, mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue; MAM-GlcUA, methylazoxymethanol-β-D-glucosiduronic acid; NHMI, N-nitrosoheptamethyleneimine; Nod, nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-containing.

Table 2.

Mechanisms by which the bacterial microbiota contribute to carcinogenesis

| Cancer | Mechanism | Evidence | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cancers promoted or inhibited by specific bacterial pathogens | |||

| Gastric cancer | Chronic infection with Helicobacter pylori |

|

39,40, 46,47 |

|

Uncontrolled adaptive immune responses in patients with chronic infection with H. pylori, Campylobacter jejuni, Borellia burgdorferi or Chlamydia psittaci |

|

52–54 |

| Gallbladder cancer | Chronic infection with Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Typhi | Epidemiology | 49,50 |

| Oesophageal cancer | Reduced risk in patients with H. pylori infection | Epidemiology | 46,48 |

| Cancers promoted by specific pathogens (in mice only) | |||

| Breast cancer | Increased inflammation, mediated by T regulatory cells | Cancer promoted in Helicobacter hepaticus-infected ApcMin/+ mice | 94 |

| Liver cancer | Chronic hepatitis | Cancer promoted in H. hepaticus-infected mice | 89 |

| Colorectal cancer | TNF-mediated and NO-mediated | Cancer promoted in H. hepaticus-infected Rag2−/− mice | 90 |

| Cancers suspected to be promoted by commensal bacteria or dysbiotic microbiomes | |||

| Colorectal cancer |

|

Cancer reduction by antibiotics and in germ-free mice; transmission of dysbiotic microbiota triggers cancer development | 25,27, 32–34,36 |

| Liver cancer |

|

|

21,22,35 |

| Lung cancer | Increased bacterial infection in COPD? |

|

24,59–62 |

| Pancreatic cancer | LPS–TLR4-mediated increase of pancreatic cancer | LPS treatment increases cancer development | 56–58 |

Apc, adenomatous polyposis coli; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DCA, deoxycholic acid; IPSID, immunoproliferative small intestinal disease; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; MALT, mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue; MAMPs, microorganism-associated molecular patterns; NO, nitric oxide; Rag2, recombination activating gene 2; TLR, Toll-like receptor; TNF, tumour necrosis factor.

Carcinogenesis triggered by specific bacterial pathogens

Gastric cancer is the prime example for bacterially driven carcinogenesis that is caused by infection with a specific bacterial pathogen30,46,47. Infection with H. pylori, which is classified as a carcinogen by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), may lead to the sequential development of gastritis, gastric ulcer, atrophy and finally gastric cancer47. With a worldwide prevalence of ~50%, and with gastric cancer occurring in 1–3% of chronically infected individuals, H. pylori infection substantially contributes to global cancer mortality47. Although identified as a carcinogenic pathogen, H. pylori-induced gastric cancer is promoted by the presence of a complex microbiota, as H. pylori mono-associated mice developed fewer tumours than their specific pathogen-free counterparts in a hypergastrinaemic transgenic mouse model30. This may be explained by H. pylori-induced gastric atrophy and hypochlorhydria, which renders the stomach susceptible to bacterial overgrowth, and subsequently increased bacterial conversion of dietary nitrates into carcinogens30. In contrast to its promotion of gastric carcinogenesis, H. pylori infection lowers the risk of oesophageal adenocarcinoma in humans46,48, which emphasizes the organ-specific effects of the bacterial microbiota in carcinogenesis.

Additional examples of carcinogenesis promoted by specific bacterial pathogens are gallbladder cancer (that is associated with chronic Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Typhi and Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Paratyphi infections49,50), and mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphomas, both of which are examples of tumours that are triggered by adaptive immune responses against specific pathogens. Gastric MALT lymphoma is characterized by clonal expansion of B cells and T helper (TH) cells that are reactive to H. pylori-derived antigens, and regression occurs after H. pylori eradication51. Similarly, infections with Campylobacter jejuni, Borrelia burgdorferi and Chlamydia psittaci are associated with certain lymphomas, and these commonly regress after antibiotic treatment52–54 (TABLES 1,2).

Cancers promoted by dysbiotic microbiomes

A wealth of studies in patients and mice has linked the microbiota to colorectal carcinogenesis55. In contrast to gastric carcinogenesis, tumour-promoting effects of the microbiota in colorectal cancer (CRC) seem to be caused by altered host–microbiota interactions and by dysbiosis, rather than by infections with specific pathogens. Accordingly, germ-free status and treatment with wide-spectrum antibiotics led to a significant reduction of the numbers of tumours in chemical and genetic experimental models of colorectal carcinogenesis25,27,32–34,36,37. The liver does not contain a known microbiome and it provides a prime example of cancer that is promoted by dysbiotic microbiota through long-distance mechanisms. Intestinal bacteria may promote liver cancer through proinflammatory MAMPs and bacterial metabolites, both of which reach the liver via the portal vein21,22,35. Notably, hepatic exposure to cancer-promoting MAMPs and metabolites is increased in liver disease, and has been linked to intestinal dysbiosis19–22. Accordingly, germ-free status and non-absorbable antibiotics reduce hepatic inflammation, fibrosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) development in mice20–22,35, whereas treatment with the TLR4 agonist lipopolysaccharide (LPS) increases HCC development21. Similar to the liver, the pancreas does not have a known microbiome. Recent studies suggest that inflammatory MAMPs, such as LPS and its receptor TLR4, promote pancreatic cancer56. Moreover, there is an association of the oral microbiome and periodontitis with pancreatic cancer57,58. However, the mechanisms by which the bacterial microbiota and MAMPs promote pancreatic cancer remain elusive.

There are considerable gaps in our knowledge about the role of the microbiota in carcinogenesis in many other organs that have a substantial bacterial microbiome, such as the lungs, skin, oral cavity and female genital tract. Several findings indicate a possible role for bacteria in the promotion of lung cancer, such as the increased bacterial colonization in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD59,60; which is a known risk factor for lung cancer development61), a lower incidence of lung cancer in germ-free male rats, and the promotion of lung cancer by LPS or by chronic respiratory infections24,62. Similarly, the reduced rate of skin cancer in germ-free rats23 and in mice lacking receptors or adaptor molecules for pro-inflammatory bacterial MAMPs63–65 also suggests a possible role for the bacterial microbiota in skin carcinogenesis.

Host–microbiota interplay in cancer

Mechanisms controlling host–microbiota interactions in the super-organism

Millions of years of evolution have seen the host and its surrounding microbial environment co-evolve into a complex super-organism in which numerous relationships such as commensalism, mutualism and parasitism are established within the ecosystem66,67. Microbial communities, which either benefit or do not harm the host, have an evolutionary advantage at establishing a permanent niche and reside in a state of immune tolerance with their host, whereas those that adopt a pathogenic relationship on entering the ecosystem activate robust innate and adaptive immune responses68. A key principle that allows the symbiotic coexistence between host and microbiota is the anatomical separation of microbial entities from the host compartment by well-maintained, multi-level barriers. Perturbation of these barriers promotes inflammation and diseases, including cancer. The barriers rely on an intact epithelial lining, sensing systems that detect and eliminate invading bacteria, and in some cases on additional features such as a mucous layer (in the gut), the stratum corneum (in the skin) and a low pH (in the skin and the stomach). Furthermore, specific cell types, such as Paneth and goblet cells in the gut and keratinocytes in the skin, monitor bacterial number and location, and regulate the microbiota through the secretion of antibacterial peptides69,70. Barriers are also enriched in specific subsets of immune cells, such as gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT), Langerhans cells in the skin and TH17 cells at mucosal surfaces70,71. In the gut, secreted immunoglobulin A represents an additional mechanism by which the host controls the microbiota; this host mechanism limits the access of intestinal antigens to the circulation and limits the invasiveness of potentially dangerous bacterial species72. Besides host mechanisms, the microbiome itself represents a functional luminal barrier73 by maintaining epithelial cell turnover, by mucin production and by competing for resources, thereby suppressing the growth of pathobionts. A prime example for the protective role of the commensal microbiota is infection with Clostridium difficile, which only thrives and causes disease when the indigenous gut microbiota is suppressed by antibiotics, and which can be cured by microbiota transplantation from healthy individuals74. Similarly, germ-free mice have an increased susceptibility to infection with pathogens75. In addition to resource competition with metabolically related strains75, commensal bacteria also suppress pathobionts and pathogens using active interference mechanisms such as the production of bacteriocins76.

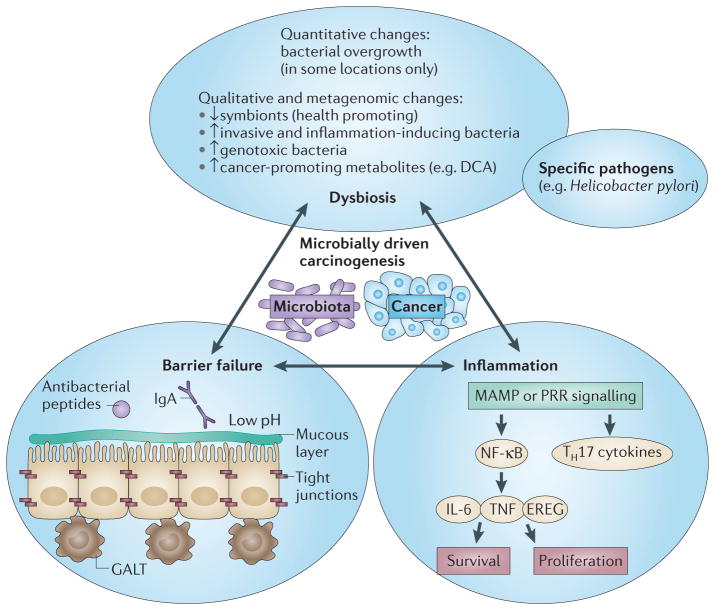

Failure of these control mechanisms — that is, barrier defects, immune defects and the loss of eubiosis — have been associated with microbially driven carcinogenesis. Importantly, regulatory mechanisms are tightly linked, and failure of one control mechanism typically perturbs the overall equilibrium (FIG. 1). As such, infection with H. pylori not only directly injures host cells, but also changes the gastric environment and barrier, increasing inflammation and altering the microbiota47. Another example of the interdependence between the barrier, immunity and the microbiota is the finding that inactivating mutations, or the absence of key components of inflammasomes — nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-containing 2 (NOD2) and NOD-, LRR- and pyrin domain-containing 6 (NLRP6) — or of interleukin-10 (IL-10), not only affect host inflammatory responses but may also lead to dysbiosis and to bacterial translocation77–79.

Figure 1. Mechanisms controlling host–microbiota interactions and associated failures implicated in cancer development.

A state of homeostasis and symbiotic relationships is maintained by the separation of microbial entities from the host through a multi-level barrier, by a eubiotic microbiome that actively suppresses pathobionts and that maintains a symbiotic relationship with the host, and by a state of low inflammation in the host. Perturbation of this balance leads to chain reactions that ultimately result in a cancer-promoting state with a failing barrier, inflammation and dysbiosis. This state includes qualitative and sometimes quantitative changes in the microbiota; failure of the barrier either physically (for example, at the level of tight junctions or at the mucous layer), or at the level of antibacterial defence systems — either those of epithelial cells or those of cells from the gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT); and increased inflammatory responses, which are often mediated by pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) and downstream cytokines that promote epithelial cell proliferation and survival. DCA, deoxycholic acid; EREG, epiregulin; IgA, immunoglobulin A; IL-6, interleukin-6; MAMP, microorganism-associated molecular pattern; NF-κB, nuclear factor-κB; TH17, T helper 17; TNF, tumour necrosis factor.

Barrier failure in carcinogenesis

The most relevant pathomechanism for bacterially driven carcinogenesis is barrier failure, which results in increased microbiota–host interactions. Barrier failure can result from primary defects in genes that encode proteins that are essential to maintain a functional barrier, or from secondary defects owing to infection, inflammation and carcinogenesis. The relationship between barrier failure and carcinogenesis is complex: barrier failure may trigger inflammation and carcinogenesis, but inflammation and carcinogenesis may also promote barrier failure, thus suggesting the existence of forward-amplifying loops. Clinically, the best known example of barrier failure is ulcerative colitis, in which defects in the intestinal barrier not only contribute to disease development but also increase the risk of cancer80. Accordingly, genome-wide association studies have found mutations in crucial barrier proteins, such as laminins, in patients with ulcerative colitis81,82.

The promotion of cancer by a defective barrier is shown by mucin 2-knockout (Muc2−/−) mice, which lack the most abundant gastrointestinal mucin and which spontaneously develop CRC83. In experimental colorectal carcinogenesis, bacterial translocation was detected at sites of tumour initiation, and eradication of the bacterial microbiota by antibiotics reduced CRC development36. Another example of barrier defects contributing to cancer development is HCC. Increased translocation of bacteria and of bacterial MAMPs, which are a hallmark of advanced liver disease19, promotes HCC development and can be reduced by germ-free status or by antibiotics21,35. Although genetic defects in the keratin-associated protein filaggrin affect the barrier function in the skin and contribute to atopic dermatitis84, they have not been associated with cancer development. Thus, barrier defects may require organ-specific ‘second hits’ to promote cancer development.

Bacterial dysbiosis in carcinogenesis

Longitudinal studies show considerable taxonomic (but little metagenomic) variation of the normal human microbiota14,85,86. Perturbations may occur through changes in diet, innate immune responses and inflammation, or infections, and may affect microbial composition, richness and the metagenome77,87,88. Besides the well-established cancer-promoting role of specific pathogens in certain cancers (TABLE 2), a contribution of specific bacteria to human carcinogenesis generally remains elusive. Additional bacterial pathogens such as Enterococcus faecalis, enterotoxigenic Bacteroides fragilis and Helicobacter hepaticus promote cancer in animal models89–94, but there is no clear epidemiological link to human carcinogenesis.

However, direct manipulation of the microbial community using germfree, gnotobiotic, antibiotic-treated and co-housed mice has revealed the essential role of commensal microbiota in CRC and HCC21,22,35,36,78,79,95,96. Indeed, thought-provoking studies involving Nod2−/−, Asc−/− (also known as Pycard−/−) and Nlrp6−/− mice, suggest that dysbiosis is sufficient to promote cancer78,79. Obesity is one of the best-studied conditions that leads to dysbiosis, with increased populations of Firmicutes and decreased populations of Bacteroidetes observed in the gut of both humans and mice88,97, as well as a decrease in microbial richness and the associated ‘dysmetabolism’ in humans98,99. Notably, obesity is a well-established risk factor for cancer development, contributing to ~15–20% of cancer100. In liver cancer, obesity causes cancer-promoting dysbiosis, with increased prevalence of Clostridia that produce the secondary bile acid deoxycholic acid (DCA), which in turn promotes HCC development22. However, direct evidence of the cancer-promoting effect of specific Clostridia strains — for example, through co-housing experiments or the use of gnotobiotic mice — is still lacking. In the colon, dietary fat increases taurocholic acid production, which leads to the expansion of the pathobiont Bilophila wadsworthia and to colitis in Il10−/− mice101, but a direct link between obesity-induced dysbiosis and CRC also remains to be established.

Microbial dysbiosis in the luminal or the mucosal compartment of patients with CRC has been reported by numerous investigators102–105, but these findings remain largely correlative. However, from these data sets, Fusobacterium spp. — particularly Fusobacterium nucleatum — emerge as a potential candidate for CRC susceptibility106–109. F. nucleatum is far less common in the gut microbiome of healthy individuals than it is in the gut microbiome of patients with Crohn’s disease110. Notably, clinically isolated F. nucleatum promotes intestinal carcinogenesis in adenomatous polyposis coli (Apc)Min/+ mice107. The F. nucleatum adhesin FadA binds to E-cadherin and activates β-catenin in CRC cells, thereby promoting inflammation and E-cadherin-mediated tumour cell growth109. Importantly, fadA levels are significantly increased in human CRC tissue samples109.

As the bacterial microbiota has a high redundancy at the metagenomic level14, it is possible that cancer-promoting effects are conferred by different classes of bacteria but through similar pathways, and that alterations in microbial richness and function (rather than true dysbiosis) affect carcinogenesis. Moreover, horizontal gene transfer occurs between pathogens and commensal bacteria, particularly in the context of pathogen-induced inflammation111, which suggests the possibility of cancer-promoting gene transfer between bacteria.

The mechanisms that contribute to dysbiosis and to alterations in microbial richness are not yet understood. Host-derived immune and inflammatory responses are an important driving force that shape the microbial community composition and, when altered, that may contribute to dysbiosis, as seen in Il10−/−, Nod2−/−, Asc−/− and Nlrp6−/− mice77–79,112. In addition to microbial regulation by innate immunity, inflammation (with its complex set of mediators) may also contribute to a milieu that favours the outgrowth of specific bacteria. Inflammation alters the production of specific metabolites, such as nitrate that is derived from the activity of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS; also known as NOS2). Nitrate may provide a unique source of energy for facultative anaerobic bacteria (for example, Enterobacteriaceae), allowing them to thrive within a community dominated by obligate anaerobic bacteria that lack the proper electron transport chain to use nitrate113. Accordingly, a bloom of Enterobacteriaceae has been observed across numerous inflammatory disease models and in patients with chronic inflammation114–116. Finally, inflammation induces expression of stress-response genes in bacteria, which is an effect that could promote bacterial fitness and adaptability117; for example, Escherichia coli from Il10−/− mice with intestinal inflammation show an increased expression of small heat shock proteins IbpA and IbpB, which protects this bacterium from oxidative stress117. Furthermore, it has been suggested that specific low-abundance microorganisms, termed ‘keystone pathogens’ or ‘alpha-bugs’, may further amplify dysbiosis in disease states by exerting dominant effects on the bacterial composition118.

Mechanisms of carcinogenesis

The microbiota is sensed by multiple pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), which monitor microbial status and barrier integrity, and which initiate regulatory responses. These PRRs may not only control the microbiota through antibacterial mediators and thereby suppress cancer, but may also promote resistance to cell death — one of the hallmarks of cancers119 — and may trigger cancer-promoting inflammation. In addition, the microbiota affects carcinogenesis through the release of carcinogenic molecules, such as genotoxins, and through the production of tumour-promoting metabolites.

Microbiota-induced activation of TLRs in carcinogenesis

Microbial pattern recognition by TLRs is a cornerstone of innate immunity and it represents one of the most powerful pro-inflammatory stimuli120. Accumulating evidence indicates that bacterial MAMPs and TLRs are contributors to carcinogenesis. TLR4, the receptor for the Gram-negative bacterial cell wall component LPS, promotes carcinogenesis in the colon, liver, pancreas and skin, as shown by reduced tumour development in Tlr4-deficient mice21,56,64,121 and by increased tumour load in mice expressing constitutively activated epithelial-derived TLR4 (REF. 122). TLR2, which is the receptor for the bacterial cell wall components peptidoglycan and lipoteichoic acid, promotes gastric cancer123. TLRs promote epithelial carcinogenesis through epithelial cells, stromal fibroblasts and through bone marrow-derived cells. A key cancer-promoting downstream effect of TLR signals is the induction of survival pathways, which is mediated by activation of nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) and signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3)21,121,123. Although there is strong evidence that tumour cells express TLRs121,123, conditional ablation strategies are required to determine whether activation of TLR signalling directly affects the survival of tumour cells, or whether tumour cell survival is indirectly affected through TLRs that are expressed in the tumour stroma. The pro-survival function of the TLR–myeloid differentiation primary response 88 (MYD88) pathway is highlighted by the finding that human lymphomas often contain an activating point mutation in MYD88 that triggers NF-κB and STAT3 activation124. In the intestine, microbiota-induced activation of TLRs on myeloid cells triggers an IL-17 and IL-23 pro-carcinogenic pathway, as shown by their decreased expression after antibiotic treatment or genetic inactivation of Myd88, Tlr2, Tlr4 or Tlr9 (REF. 36). Importantly, carcinogenesis is reduced by genetic or pharmacological inhibition of IL-17 and IL-23 signalling36,92. TLRs may also promote tumour proliferation, which is thought to be mediated through mitogens such as epiregulin, amphiregulin and hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) that are released from TLR-expressing stromal fibroblasts; this has been shown in the colon and in the liver21,121,125,126.

It should be emphasized that signalling pathways used by TLRs, such as MYD88, often have multiple functions, and that complete ablation not only affects malignant cells but also affects the function of normal epithelia. In the intestinal epithelium, MYD88 functions as a gatekeeper of epithelial integrity. This may explain why MYD88 deficiency not only suppresses the development of cancer127–130 but also promotes carcinogenesis in models with substantial epithelial damage, such as in the model of dextran sodium sulphate (DSS)-promoted CRC56,131. The increased damage possibly masks potential tumour-suppressive effects of reduced MYD-88-mediated inflammation in these models. MYD88 is also a mediator of IL-18 signalling, and the absence of MYD88 may therefore promote carcinogenesis by blocking the activity of an IL-18-dependent pathway that influences microbial composition (discussed below).

Microbiota-induced activation of NLRs in carcinogenesis

NLRs are a family of PRRs that are characterized by a central NOD domain112. NOD2, a muramyl dipeptide-sensing NLR, has been the focus of many studies because its loss of activity is associated with Crohn’s disease80. Notably, inactivating polymorphisms in NOD2 have been associated with increased susceptibility to CRC in several cohorts132. Similar to what is seen in patients with Crohn’s disease, Nod2 deficiency leads to increased CRC in mice78. NOD2 exerts a key role in bacterial immunity, as shown by the increased susceptibility of NOD2-deficient mice to bacterial infections, and by the decreased ability of NOD2-deficient crypts to kill commensal bacteria133,134. Interestingly, Nod2−/− mice, as well as patients with NOD2 mutations, also have intestinal dysbiosis135. Indeed, a thought-provoking study has recently suggested that the increased cancer susceptibility in NOD2-deficient mice is a consequence of dysbiosis, as the increased cancer development was transferable to wild-type mice by co-housing78.

A second NLR implicated in the host–microbiota interaction and in bacterially driven carcinogenesis is NLRP6. NLRP6 is a component of inflammasomes and it contributes to their activation, as shown by decreased levels of IL-18 in Nlrp6−/− mice79. Similar to Nod2−/− mice, Nlrp6−/− mice have dysbiosis that makes them more susceptible to colitis and CRC development. The dysbiosis-driven carcinogenesis in Nlrp6−/− mice is a result of decreased inflammasome activation and IL-18 production, as shown by the increased susceptibility of Asc−/− and Il18−/− mice to CRC, and by the ability of these mice to transmit this disease to wild-type mice in co-housing studies79. IL-6 represents a common mediator of the tumour-promoting effects of dysbiotic Nod2−/− and Nlrp6−/− mice, as shown by reduced CRC development in mice that are treated with neutralizing IL-6 receptor (IL-6R) antibodies and in mice with Il6r ablation78,79. NOD1 also has a role in intestinal defence against bacteria, and NOD1 variants have been implicated in inflammatory bowel disease in humans136. Notably, NOD1 deficiency negatively affects the intestinal barrier and it promotes inflammation- and genetically-induced CRC, which can be suppressed by depletion of the gut microbiota by antibiotic treatment34. Other NLRs such as NLRP3, NLRP12 and NOD-, LRR- and CARD-containing 4 (NLRC4) also have a role in colitis-associated cancer137–139, but the functional contribution of these innate sensors to microbially driven carcinogenesis remains unclear.

Bacterial-derived genotoxins

Although the ability of some bacteria to induce chronic inflammation (and an associated increase in reactive oxygen species (ROS)-mediated genotoxicity) clearly contributes to their carcinogenic potential, microorganisms also have the capacity to directly modulate tumorigenesis through specific toxins that induce DNA damage responses (FIG. 2). As discussed above, alterations in barrier function may allow luminal bacteria (such as adherent-invasive E. coli) access to the epithelium, where direct contact with host cells enables the bacteria to transfer or to deliver specific toxins. Bacterial toxins, such as cytolethal distending toxin (CDT), cytotoxic necrotizing factor 1, B. fragilis toxin and colibactin, affect crucial cellular responses that are implicated in tumorigenesis, particularly responses to DNA damage77,92,140–142. However, only CDT and colibactin exert direct DNA damage responses and genomic instability, and are therefore considered genotoxic141,142. Both of these genotoxins trigger double-strand DNA damage responses, including activation of the ataxia-telangiectasia mutated (ATM)–CHK2 signalling pathway and phosphorylation of histone H2AX, which lead to transient G2/M cell cycle arrest and to cell swelling.

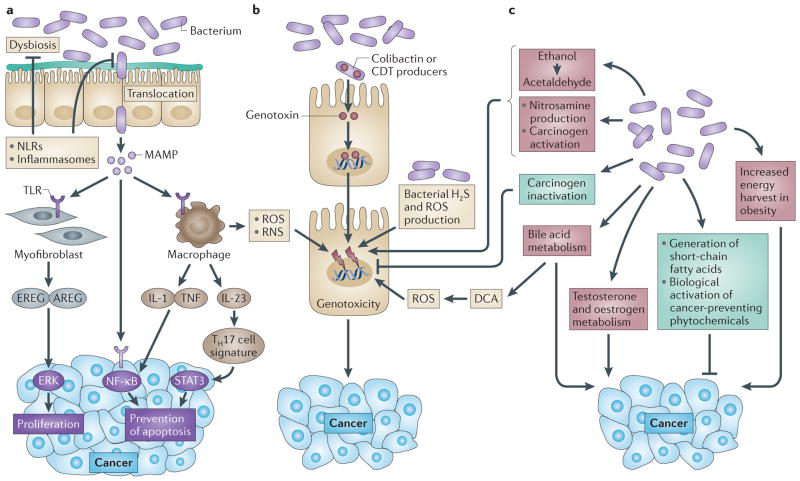

Figure 2. Mechanisms by which the bacterial microbiome modulates carcinogenesis.

The bacterial microbiome promotes carcinogenesis through several mechanisms. a | Changes in the microbiome and host defences may favour increased bacterial translocation, leading to increased inflammation, which is mediated by microorganism-associated molecular patterns (MAMPs) that activate Toll-like receptors (TLRs) in several cell types, including macrophages, myofibroblasts, epithelial cells and tumour cells. These effects may occur locally or through long-distance effects in other organs. b | Genotoxic effects are mediated by bacterial genotoxins — such as colibactin and cytolethal distending toxin (CDT) — that, after being delivered to the nucleus of host cells, actively induce DNA damage in organs that are in direct contact with the microbiome, such as the gastrointestinal tract. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS) released from inflammatory cells such as macrophages, as well as hydrogen sulphide (H2S) from the bacterial microbiota, may also be genotoxic. c | Metabolic actions of the microbiome may result in the activation of genotoxins such as acetaldehyde, dietary nitrosamine and other carcinogens, in the metabolism of hormones such as oestrogen and testosterone, in the metabolism of bile acids and in alterations of energy harvest. The microbiota also mediates tumour suppressive effects (shown in green) through inactivation of carcinogens, through the generation of short-chain fatty acids such as butyrate and through the biological activation of cancer-preventing phytochemicals. Many of these tumorigenic and tumour-suppressive mediators exert both local and longdistance effects. AREG, amphiregulin; DCA, deoxycholic acid; EREG, epiregulin; IL, interleukin; NF-κB, nuclear factor-κB; NLR, NOD-like receptor; STAT3, signal transducer and activator of transcription 3; TH17, T helper 17; TNF, tumour necrosis factor.

CDT is produced by Gram-negative bacteria and is by far the most wellcharacterized genotoxin. Microorganisms relevant to colorectal, gastric and gallbladder cancer (such as E. coli, Helicobacter spp. and S. Typhi) are all CDT producers143. Upon infection, the CdtA and CdtC subunits form an anchor between the bacterium and the host cell to allow delivery of the active subunit CdtB into the cytoplasm, from where it travels to the nucleus and confers DNase activity-mediated DNA damage141. Mutation of residues in the active site of CdtB, which are highly homologous to those in mammalian DNase I sites, reduces DNA damage responses in vitro, including cell cycle arrest141,144. CDT-mediated DNase activity may also be important for the carcinogenic potential of CDT-carrying bacteria, such as C. jejuni and Helicobacter cinaedi, because CdtB-mutant strains failed to elicit intestinal hyperplasia in mice lacking NF-κB subunits, p50 (also known as Nfkb1) and one allele of p65 (also known as Rela), and failed to elicit dysplasia in Il10−/− mice145,146.

Colibactin, which is encoded in the 54 kb polyketide synthase (pks) genotoxicity island, is another important genotoxin that has attracted recent attention. pks-containing bacteria mostly belong to the Enterobacteriaceae family, with E. coli from the B2 groups representing the predominant carrier147. Recently, the murine isolate E. coli NC101 pks was functionally linked to CRC development in gnotobiotic Il10−/− mice77, and the pks island was more prevalent in mucosa-associated E. coli clinical isolates obtained from patients with CRC compared with those obtained from controls77,148. Interestingly, Proteus mirabilis and Klebsiella pneumoniae, two microorganisms that can induce a maternally transmissible colitis in immunodeficient mice that are deficient in both T-bet (also known as TBX21) and recombination activating gene 2 (RAG2; Tbet−/−Rag2−/− mice) 149, are also pks carriers150. Whether P. mirabilis, K. pneumoniae and colibactin are functionally implicated in the development of CRC observed in Tbet−/−Rag2−/− mice95 remains to be determined. Colibactin has not been isolated and purified, but it is known that eight of nine accessory genes, and all the PkS and nonribosomal peptide synthetase (NRPS) subunits, are required to generate active colibactin with DNA-damaging capacity147. At the molecular level, E. coli pks-positive strains induce double-strand DNA breaks and associated DNA damage responses (mediated by ATM), cell cycle arrest and genomic instability77,142. Colibactin genotoxicity and carcinogenic effects might be mediated by DNase activity. This hypothesis is supported by the finding that DNA integrity in cells infected with E. coli pks+ strains is compromised compared with pks-defective isogenic mutants147. Whether this effect is the direct result of colibactin, as is the case for CDT, or is due to an intermediate target, needs further investigation.

Moreover, various bacterial-derived metabolites such as hydrogen sulphide and superoxide radicals may cause genomic instability151,152. For example, Enterococcus faecalis can generate large amounts of extracellular superoxide, which causes double-strand DNA breaks and chromosome instability152,153; this leads to the development of CRC in Il10−/− mice154,155. E. faecalis mutants that are defective in extracellular superoxide production (for example, ΔmenB strain) fail to promote tumorigenesis in Il10−/− mice compared with mice colonized with the parental E. faecalis strain154,155. Sulphate-reducing bacteria — which mostly belong to the class of Fusobacteria (which has recently been linked to CRC106,156 and tumour development in preclinical models107) and to the class Deltaproteobacteria — promote the generation of hydrogen sulphide, which is a gas with genotoxic properties157. Host-mediated detoxification and/or microbial-mediated elimination (or use) of these genotoxic products are likely to have an effect on host cellular homeostasis and on carcinogenesis.

Bacterial virulence factors

Disease-promoting and cancer-promoting effects of pathogens often depend on virulence factors. This is exemplified by increased inflammation and cancer rates in H. pylori strains expressing the virulence factors cytotoxin-associated gene A (CagA) or vacuolating cytotoxin A (VacA)47. Virulence factors may use specific host-derived signalling pathways that result in the activation of tumour-promoting pathways, as demonstrated by the activation of the tyrosine phosphatase SHP2 (also known as PTPN11) and by the development of gastric cancers in transgenic mice expressing CagA, but not phosphorylation-resistant CagA158. In addition, F. nucleatum uses the virulence factor FadA to adhere to and invade cells159, and was recently shown to interact with E-cadherin to activate β-catenin signalling and to promote CRC development109. Virulence factors found in other pathogens and commensal bacteria are likely to contribute to carcinogenesis, but this requires further investigation.

Microbial-derived metabolism affecting carcinogenesis

Human metabolism represents a combination of microbial and human enzyme activities11. The bacterial metagenome is functionally far more diverse than that of humans, and is enriched for genes that are relevant for nutrient, bile acid and xenobiotic metabolism, as well as for the biosynthesis of vitamins and isoprenoids11,160. These metabolic activities, generated by the oral and intestinal microbiota, may affect carcinogenesis by regulating obesity and obesity-induced inflammation, metabolic activation and inactivation of carcinogens (which includes the generation of nitrosamines and the conversion of alcohol to acetaldehyde), metabolic activation or inactivation of dietary phytochemicals, metabolism of hormones and the generation of tumour-promoting secondary bile acids.

Gut bacteria regulate bile acid metabolism through various hydrolase activities, which remove polar groups — for example, taurine — from conjugated bile acids, thereby affecting bile acid composition and enterohepatic circulation, and allowing microorganisms to use secondary bile acids as an energy source160. Recent studies suggest that a high-fat diet alters the gut microbiome and increases the levels of the secondary bile acid DCA, which is a metabolite that is solely produced by bacterial 7α-dehydroxylation. Notably, in this high-fat diet model, DCA supplementation increases HCC development, whereas reduction of DCA-producing bacteria by antibiotics decreases it22. DCA is also known to promote colon and oesophageal cancer, which suggests that the microbiome may also affect these cancers through DCA production, particularly in the context of obesity22,161,162.

Microbial carbohydrate fermentation may benefit the host through the generation of short-chain fatty acids163, whereas protein fermentation may have negative consequences owing to the generation of potentially toxic and cancer-promoting metabolites, such as ammonia, amines, phenols, sulphides and nitrosamines151,164–166. As protein fermentation mainly occurs in the distal colon, this might contribute to the higher rate of cancers in the distal (small) versus the proximal (large) intestine. High-protein, low-carbohydrate diets may change intestinal fermentation, leading to increased levels of hazardous metabolites, such as nitrosamines, and to decreased levels of cancer- protective metabolites, such as butyrate and plant-derived phenolic compounds167. In particular, short-chain fatty acids incuding butyrate have a known role in the regulation of inflammation and autophagy, and have been implicated in protection from colon and liver cancer168–171. Health-promoting, antioxidant and cancer-preventing properties of plant-derived products are often attributed to phytochemicals, including polyphenols such as theaflavins, thearubigins, epigallocatechin-3-gallate and flavonoids172–174. Through its large enzymatic capacity, the microbiota synthesizes, bioconverts or degrades isoprenoids and polyphenols (including flavonoids), thus controlling their local and systemic effects on health and cancer development11,173,175–178. The gut microbiota also modulates the biological activity of lignans177,179, a class of phytooestrogens that reduces cancer incidence180, thereby affecting cancer development. Although the microbiota is necessary for phytochemical-mediated anticancer properties, the microbial entities and complex partnerships that contribute to these beneficial effects remain unclear.

The intestinal microbiota also has a major role in the metabolism of xenobiotics181. As such, it influences the activity and the side effects of drugs used for antitumour therapies. For example, irinotecan is inactivated by the liver but reactivated by bacterial β-glucoronidase, which leads to severe treatment-limiting side effects such as diarrhoea182; notably, treatment with antibiotics or inhibitors of bacterial β-glucoronidase prevents these complications182.

The microbiota also contributes to the activation28,183,184 and the inactivation of carcinogens185,186, thereby modulating carcinogenesis. Importantly, the bacterial microbiota contributes to the metabolism of alcohol, which is responsible for ~3.6% of all cancers187, including cancers of the oral cavity, pharynx, oesophagus, colon, rectum, female breast and liver. Germ-free rats have significantly lower concentrations of acetaldehyde188, which mediates many of the disease-promoting and genotoxic effects of alcohol187. The contribution of bacterial acetaldehyde generation may be particularly important in cancers of the oral cavity, where further metabolism of acetaldehyde is limited, leading to 10–100-fold higher acetaldehyde concentrations than in the blood187.

The bacterial microbiota may also have a role in the metabolism of hormones, including oestrogens189 and testosterone190. In particular, the microbiota modulates the enterohepatic circulation of oestrogens through their ability to deconjugate oestrogens, thus affecting circulating and excreted oestrogen levels189, and the risk for development of oestrogen-dependent cancers189.

In summary, the intricate relationship between the microbiota and the host in respect to tumour-promoting and tumour-suppressive components of our diets and lifestyles is only starting to be appreciated. Consumption of unhealthy diets, obesity, alcohol and smoking are all known to modulate microbiomes and to contribute to carcinogenesis. The relative contribution of microbiomes and microbial metabolism to the carcinogenesis that is promoted by these unhealthy lifestyles remains to be determined.

Open questions and crucial issues

Although the link between the microbiota and cancer has been recognized, several key questions remain unanswered in this rapidly evolving field of research.

Evidence for a contribution of microbiomes in human carcinogenesis

The functional relevance of human microbiomes to cancer development has not been established. Transferring human cancer microbiomes to preclinical models would help to assess the tumorigenic potential of the cancer-associated microbiota. However, experiments using cross-species transplantation need to take into account host-specific microbiota effects on the immune system191, which are an important component of the carcinogenic process.

Multifaceted and large-scale approaches that integrate metagenomic, metatranscriptomic and metabolomic analysis from large cohorts of patients and healthy controls will be essential in establishing the role that microbiomes have in cancer development, in an organ- and cancer-specific manner, and will allow investigators to determine whether changes in microbial composition or richness, in particular at the metagenomic level, affect cancer development. Validation of the cancer-inducing potential of clinical bacterial isolates would require the use of various animal models, combined with different housing conditions — specific pathogen-free (SPF) and germ-free conditions, as well as gnotobiotics — to clearly establish cause–effect relationships. Furthermore, testing clinical isolates in more than one model is also important as, for example, F. nucleatum promotes colorectal cancer in ApcMin/+ mice but not in Il10−/− mice107.

The contribution of extra-intestinal microbiomes to carcinogenesis

Most current data on the microbiota and cancer focus on the gut microbiome. Although the gut microbiome dominates in number, other microbiomes may also have relevance to cancer; for example, the contribution of the lung microbiome to lung cancer is clearly understudied, and understanding this possible link may be relevant. Similarly, further insight into the roles of microbiomes of the skin and the urogenital tract could be highly relevant.

Identification of bacteria and bacterial mediators or metabolites that promote cancer

Identification of key contributors to microbiota-driven carcinogenesis is required to develop therapeutic approaches. Innovative techniques, including novel cultivation media, particularly for anaerobic conditions192, and novel culture techniques such as microfluidic continuous cultures193 will be necessary to overcome the limited range of bacteria that can currently be cultured and that can subsequently be characterized in vitro or in gnotobiotic animal models. Although gnotobiotic models are a powerful tool to understand microbial contributions to carcinogenesis, this experimental approach does not reflect the complex composition of the microbiome that is found in humans; indeed, it may either overemphasize effects owing to artificial abundance of a single species or of a group of bacteria, or it may not reveal effects that are due to the requirement of a complex microbial community for the induction of disease by some bacteria149. It will be important to identify the environmental conditions that lead to under-representation and overrepresentation of bacterial species that are associated with cancer, and to mimic these conditions in experimental models.

In addition to identifying the specific bacteria that contribute to carcinogenesis, the identification of the mediators through which these bacteria promote cancer is essential to advance therapeutic interventions. The recent discovery of the roles of bacterial genotoxins and secondary bile acid metabolites as key effectors in mouse carcinogenesis is a first step towards understanding how bacteria may directly promote cancer. Large-scale and deep-sequencing analyses, in combination with proteomics and metabolomics, are likely to uncover additional genotoxic islands and cancer-promoting metabolites or other factors present in clinical isolates.

The interplay between inflammation and the microbiome in carcinogenesis

Although inflammation is an important environmental trigger that shapes microbial composition194,195, it is not clear whether dysbiosis is fostered by the progression of inflammatory grades or whether other factors (such as host genetics or diet) imprint early microbial dysbiosis, which then promotes inflammation. This cause–effect relationship will need to be investigated in more detail using longitudinal microbiome analysis in conjunction with the measurement of inflammatory markers. Similarly, the functional effect of innate sensors such as TLR2, TLR4 and TLR5 on microbial composition has been questioned196; for example, although the dysbiotic microbiota from Nod2−/− mice transfers carcinogenesis to wild-type mice78, several groups have found no evidence of dysbiosis in Nod2−/− mice197,198. These findings do not negate the observation that the microbiota could transfer a given disease phenotype, but they certainly do question the causative link between a specific genotype (for example, Nod2−/−) and dysbiosis. This highlights the need to carry out additional experiments in which familial transmission196 and stochastic changes199 are carefully monitored and assessed before firm conclusions are reached about dysbiosis and the host genotype. Moreover, many PRRs not only regulate innate immunity and inflammation but also regulate barrier integrity. An alternative mechanistic explanation for the effects of PRRs in carcinogenesis could be that a breach of barriers owing to insufficient PRR activity constitutes the key trigger in microbially driven inflammation and carcinogenesis. In this scenario, dysbiosis could be an epiphenomenon to the pathology.

Another important unanswered question is the relationship between the microbiome and cancer therapeutic responses. Although the influence of the gut microbiota in shaping local and systemic immune responses has been recognized195, the effect of this biological function on the efficacy of antitumour agents is unknown.

Possible future therapeutic applications

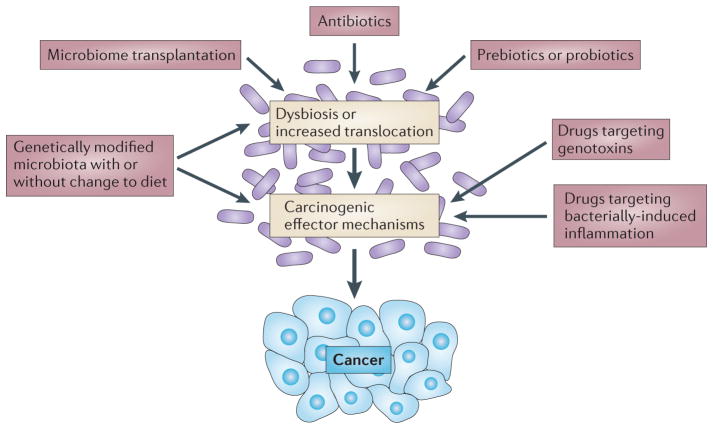

The many mechanisms by which the microbiota modulates carcinogenesis, including inflammation, metabolism and genotoxicity (FIG. 2), provide possibilities to target the microbiome for cancer prevention strategies. Although additional data linking the contribution of the microbiome to specific cancers, particularly in humans, need to be generated, microbiota-based strategies for cancer prevention can be envisioned (FIG. 3). Prebiotics, probiotics or microbiota transplants may restore eubiosis in chronic disease states, thereby reducing microbially-induced genotoxicity and activation of inflammatory, proliferative and antiapoptotic pathways. Limited-spectrum and non-absorbable antibiotics may be used to target genotoxic, DCA-producing or translocating bacteria; for example, in patients at a high risk of developing CRC or HCC. Genetically altered microbiota expressing or lacking specific enzymes200 — in combination with matched diets — might be used to achieve higher levels of tumour-suppressive phytochemicals or lower levels of tumour-promoting substances, or to suppress tumour-promoting bacterial species. Pharmacological targeting of inflammatory pathways that are activated by the bacterial microbiota may reduce cancer-promoting inflammation, and pharmacological approaches may be used to target bacterial genotoxins and enzymes that promote cancer.

Figure 3. Targeting the bacterial microbiota for therapeutic modulation of carcinogenesis.

On the basis of the known contribution of the bacterial microbiota in experimental carcinogenesis, the approaches shown are conceivable for the prevention of human carcinogenesis.

Understanding the diverse contributions of the bacterial microbiota to carcinogenesis will open new possibilities for diagnostic, preventative and therapeutic approaches. Although it is likely that many of the underlying mechanisms are disease- or organspecific, mining the microbiome holds much promise and clearly represents the next frontier of medical research.

Acknowledgments

R.F.S. was supported by grants from the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) U54CA163111, R01DK076920 and R01AA020211. C.J. acknowledges support from the NIH (RO1DK047700 and RO1DK073338). The authors thank D. Dapito for critical reading of the manuscript.

Glossary

- Adaptive immune responses

As opposed to innate immunity, adaptive immune responses are specific to the type of pathogen that is encountered, thereby providing a tailored (albeit slower) immune response. This acquired response is typically mediated by B and T cells with the subsequent generation of memory cells

- Bacteriocins

Antimicrobial peptides released by bacteria to inhibit growth of similar or closely related microorganisms

- Commensalism

A relationship between two organisms in which one organism benefits, whereas the other does not

- Dysbiosis

A state of microbial composition that is characterized by an unbalanced proportion of bacteria compared with the proportion in a healthy state

- Eubiosis

A state of microbial composition in which population abundances are found in normal proportions and typically associated with healthy individuals

- Facultative anaerobic bacteria

Bacteria that are able to generate energy (ATP) through aerobic respiration (electron transport chain) or through fermentation, depending on the amount of oxygen or fermentable products available

- Germ-free animals

Animals born and raised in a sterile environment; they lack any microorganisms (except endogenous viruses)

- Gnotobiotic

Describes an animal with a defined microbial population. These animals are born germ-free and then known microorganisms are introduced; this requires that the animals are housed in isolation, to maintain their defined microbial status

- Horizontal gene transfer

The movement of genetic material from one organism to another, without the need for cell division

- Innate immunity

An immune response that recognizes conserved microbial structures, typically through the action of pattern recognition receptors expressed on host cells

- Metagenome

The collection of genomes from members of a specific microbiota

- Microorganism-associated molecular patterns (MAMPs)

Conserved structural components such as lipopolysaccharide, flagellin and nucleic acids derived from microorganisms that are detected by the host innate immune system

- Muramyl dipeptide

A peptidoglycan derivative that is common to both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacterial cell walls and that triggers an innate immune response

- Mutualism

A relationship between two organisms, in which both organisms benefit

- Obligate anaerobic bacteria

Bacteria that grow without the need for oxygen

- Parasitism

A relationship in which one organism (pathogen) benefits at the expense of another organism

- Pathobionts

Normally innocuous microorganisms that can behave like pathogens if their abundance increases and/or their environmental conditions change

- Stratum corneum

The outermost layer of the epidermis that forms the protective layer of the skin

- Toll-like receptor (TLR)

A family of evolutionarily conserved receptors that recognize microorganism-associated molecular patterns such as flagellin, lipopolysaccharide or nucleic acids. These receptors have an essential role in innate immune responses

- Tumour tolerance

A state of immune hyporesponsiveness, in which tumour antigens induce T cell tolerance (a process that allows tumour immune evasion)

- Virulence factors

Molecules expressed by pathogenic microorganisms that help them to gain a growth advantage in a specific ecosystem. These molecules are often responsible for disease manifestation in the host

Footnotes

Competing interests statement

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Contributor Information

Robert F. Schwabe, Email: rfs2102@columbia.edu, Department of Medicine, and Institute of Human Nutrition, Columbia University, College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York 10032, USA

Christian Jobin, Email: Christian.Jobin@medicine.ufl.edu, Department of Medicine and Department of Infectious Diseases & Pathology, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida 32611, USA.

References

- 1.Koch R. Tenth International Congress of Medicine 1. August Hirschwald; Berlin: 1891. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balkwill F, Mantovani A. Inflammation and cancer: back to Virchow? Lancet. 2001;357:539–545. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04046-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Trinchieri G. Cancer and inflammation: an old intuition with rapidly evolving new concepts. Annu Rev Immunol. 2012;30:677–706. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-075008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moore PS, Chang Y. Why do viruses cause cancer? Highlights of the first century of human tumour virology. Nature Rev Cancer. 2010;10:878–889. doi: 10.1038/nrc2961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Virchow R. In: Die krankhaften Geschwülste. Virchow R, editor. Verlag von August von Hirschwald; Berlin: 1863. pp. 57–101. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grivennikov SI, Greten FR, Karin M. Immunity, inflammation, and cancer. Cell. 2010;140:883–899. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Turnbaugh PJ, et al. An obesity-associated gut microbiome with increased capacity for energy harvest. Nature. 2006;444:1027–1031. doi: 10.1038/nature05414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith MI, et al. Gut microbiomes of Malawian twin pairs discordant for kwashiorkor. Science. 2013;339:548–554. doi: 10.1126/science.1229000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O’Hara AM, Shanahan F. The gut flora as a forgotten organ. EMBO Rep. 2006;7:688–693. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Savage DC. Microbial ecology of the gastrointestinal tract. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1977;31:107–133. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.31.100177.000543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gill SR, et al. Metagenomic analysis of the human distal gut microbiome. Science. 2006;312:1355–1359. doi: 10.1126/science.1124234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kau AL, Ahern PP, Griffin NW, Goodman AL, Gordon JI. Human nutrition, the gut microbiome and the immune system. Nature. 2011;474:327–336. doi: 10.1038/nature10213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fraher MH, O’Toole PW, Quigley EM. Techniques used to characterize the gut microbiota: a guide for the clinician. Nature Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;9:312–322. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2012.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Consortium HMP. Structure, function and diversity of the healthy human microbiome. Nature. 2012;486:207–214. doi: 10.1038/nature11234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Colditz GA, Sellers TA, Trapido E. Epidemiology — identifying the causes and preventability of cancer? Nature Rev Cancer. 2006;6:75–83. doi: 10.1038/nrc1784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peto J. Cancer epidemiology in the last century and the next decade. Nature. 2001;411:390–395. doi: 10.1038/35077256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grice EA, Segre JA. The skin microbiome. Nature Rev Microbiol. 2011;9:244–253. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eckburg PB, et al. Diversity of the human intestinal microbial flora. Science. 2005;308:1635–1638. doi: 10.1126/science.1110591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wiest R, Garcia-Tsao G. Bacterial translocation (BT) in cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2005;41:422–433. doi: 10.1002/hep.20632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seki E, et al. TLR4 enhances TGF-β signaling and hepatic fibrosis. Nature Med. 2007;13:1324–1332. doi: 10.1038/nm1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dapito DH, et al. Promotion of hepatocellular carcinoma by the intestinal microbiota and TLR4. Cancer Cell. 2012;21:504–516. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yoshimoto S, et al. Obesity-induced gut microbial metabolite promotes liver cancer through senescence secretome. Nature. 2013;499:97–101. doi: 10.1038/nature12347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sacksteder MR. Occurrence of spontaneous tumors in the germfree F344 rat. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1976;57:1371–1373. doi: 10.1093/jnci/57.6.1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schreiber H, Nettesheim P, Lijinsky W, Richter CB, Walburg HE. Jr Induction of lung cancer in germfree, specific-pathogen-free, and infected rats by N-nitrosoheptamethyleneimine: enhancement by respiratory infection. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1972;49:1107–1114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reddy BS, et al. Colon carcinogenesis with azoxymethane and dimethylhydrazine in germ-free rats. Cancer Res. 1975;35:287–290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reddy BS, Watanabe K. Effect of intestinal microflora on 2,2′-dimethyl-4-aminobiphenyl-induced carcinogenesis in F344 rats. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1978;61:1269–1271. doi: 10.1093/jnci/61.5.1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reddy BS, Weisburger JH, Narisawa T, Wynder EL. Colon carcinogenesis in germ-free rats with 1,2-dimethylhydrazine and N-methyl-N′-nitro- N-nitrosoguanidine. Cancer Res. 1974;34:2368–2372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Laqueur GL, Matsumoto H, Yamamoto RS. Comparison of the carcinogenicity of methylazoxymethanol-β-D-glucosiduronic acid in conventional and germfree Sprague-Dawley rats. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1981;67:1053–1055. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Uronis JM, et al. Modulation of the intestinal microbiota alters colitis-associated colorectal cancer susceptibility. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e6026. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lofgren JL, et al. Lack of commensal flora in Helicobacter pylori-infected INS-GAS mice reduces gastritis and delays intraepithelial neoplasia. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:210–220. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.09.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li Y, et al. Gut microbiota accelerate tumor growth via c-jun and STAT3 phosphorylation in APCMin/+ mice. Carcinogenesis. 2012;33:1231–1238. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgs137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vannucci L, et al. Colorectal carcinogenesis in germfree and conventionally reared rats: different intestinal environments affect the systemic immunity. Int J Oncol. 2008;32:609–617. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dove WF, et al. Intestinal neoplasia in the ApcMin mouse: independence from the microbial and natural killer (beige locus) status. Cancer Res. 1997;57:812–814. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen GY, Shaw MH, Redondo G, Nunez G. The innate immune receptor Nod1 protects the intestine from inflammation-induced tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2008;68:10060–10067. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yu LX, et al. Endotoxin accumulation prevents carcinogen-induced apoptosis and promotes liver tumorigenesis in rodents. Hepatology. 2010;52:1322–1333. doi: 10.1002/hep.23845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grivennikov SI, et al. Adenoma-linked barrier defects and microbial products drive IL-23/IL-17-mediated tumour growth. Nature. 2012;491:254–258. doi: 10.1038/nature11465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Klimesova K, et al. Altered gut microbiota promotes colitis-associated cancer in IL-1 receptor-associated kinase M-deficient mice. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:1266–1277. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0b013e318281330a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee CW, et al. Helicobacter pylori eradication prevents progression of gastric cancer in hypergastrinemic INS-GAS mice. Cancer Res. 2008;68:3540–3548. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ma JL, et al. Fifteen-year effects of Helicobacter pylori, garlic, and vitamin treatments on gastric cancer incidence and mortality. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104:488–492. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wong BC, et al. Helicobacter pylori eradication to prevent gastric cancer in a high-risk region of China: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291:187–194. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.2.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Coley WB. Treatment of inoperable malignant tumors with the toxins of erysipelas and the Bacillus prodigiosus. Trans Amer Surg Assn. 1894;12:183–212. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Starnes CO. Coley’s toxins in perspective. Nature. 1992;357:11–12. doi: 10.1038/357011a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shear MJ, Andervont HB. Chemical treatment of tumors. III separation of hemorrhage-producing fraction of B coli filtrate. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 1936;34:323–324. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pradere JP, Dapito DH, Schwabe RF. The yin and yang of toll-like receptors in cancer. Oncogene. 2013 doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.302. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/onc.2013.302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Garaude J, Kent A, van Rooijen N, Blander JM. Simultaneous targeting of Toll- and NOD-like receptors induces effective tumor-specific immune responses. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4:120ra16. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Peek RM, Jr, Blaser MJ. Helicobacter pylori and gastrointestinal tract adenocarcinomas. Nature Rev Cancer. 2002;2:28–37. doi: 10.1038/nrc703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fox JG, Wang TC. Inflammation, atrophy, and gastric cancer. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:60–69. doi: 10.1172/JCI30111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Islami F, Kamangar F. Helicobacter pylori and esophageal cancer risk: a meta-analysis. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2008;1:329–338. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-08-0109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Caygill CP, Hill MJ, Braddick M, Sharp JC. Cancer mortality in chronic typhoid and paratyphoid carriers. Lancet. 1994;343:83–84. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)90816-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Welton JC, Marr JS, Friedman SM. Association between hepatobiliary cancer and typhoid carrier state. Lancet. 1979;1:791–794. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(79)91315-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wotherspoon AC, et al. Regression of primary low-grade B-cell gastric lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue type after eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Lancet. 1993;342:575–577. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)91409-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lecuit M, et al. Immunoproliferative small intestinal disease associated with Campylobacter jejuni. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:239–248. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa031887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Senff NJ, et al. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer and International Society for Cutaneous Lymphoma consensus recommendations for the management of cutaneous B-cell lymphomas. Blood. 2008;112:1600–1609. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-04-152850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ferreri AJ, et al. Chlamydophila psittaci eradication with doxycycline as first-line targeted therapy for ocular adnexae lymphoma: final results of an international phase II trial. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2988–2994. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.41.4466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Grivennikov SI. Inflammation and colorectal cancer: colitis-associated neoplasia. Semin Immunopathol. 2012;35:229–244. doi: 10.1007/s00281-012-0352-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ochi A, et al. MyD88 inhibition amplifies dendritic cell capacity to promote pancreatic carcinogenesis via Th2 cells. J Exp Med. 2012;209:1671–1687. doi: 10.1084/jem.20111706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Michaud DS, Joshipura K, Giovannucci E, Fuchs CS. A prospective study of periodontal disease and pancreatic cancer in US male health professionals. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:171–175. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djk021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Farrell JJ, et al. Variations of oral microbiota are associated with pancreatic diseases including pancreatic cancer. Gut. 2012;61:582–588. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pragman AA, Kim HB, Reilly CS, Wendt C, Isaacson RE. The lung microbiome in moderate and severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e47305. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sethi S, Murphy TF. Infection in the pathogenesis and course of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2355–2365. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0800353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Houghton AM. Mechanistic links between COPD and lung cancer. Nature Rev Cancer. 2013;13:233–245. doi: 10.1038/nrc3477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Melkamu T, Qian X, Upadhyaya P, O’Sullivan MG, Kassie F. Lipopolysaccharide enhances mouse lung tumorigenesis: a model for inflammation-driven lung cancer. Vet Pathol. 2013;50:895–902. doi: 10.1177/0300985813476061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Swann JB, et al. Demonstration of inflammation-induced cancer and cancer immunoediting during primary tumorigenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:652–656. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708594105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mittal D, et al. TLR4-mediated skin carcinogenesis is dependent on immune and radioresistant cells. EMBO J. 2010;29:2242–2252. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cataisson C, et al. IL-1R–MyD88 signaling in keratinocyte transformation and carcinogenesis. J Exp Med. 2012;209:1689–1702. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Backhed F, Ley RE, Sonnenburg JL, Peterson DA, Gordon JI. Host–bacterial mutualism in the human intestine. Science. 2005;307:1915–1920. doi: 10.1126/science.1104816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dethlefsen L, McFall-Ngai M, Relman DA. An ecological and evolutionary perspective on human-microbe mutualism and disease. Nature. 2007;449:811–818. doi: 10.1038/nature06245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Eloe-Fadrosh EA, Rasko DA. The human microbiome: from symbiosis to pathogenesis. Annu Rev Med. 2013;64:145–163. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-010312-133513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Salzman NH, Underwood MA, Bevins CL. Paneth cells, defensins, and the commensal microbiota: a hypothesis on intimate interplay at the intestinal mucosa. Semin Immunol. 2007;19:70–83. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2007.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nestle FO, Di Meglio P, Qin JZ, Nickoloff BJ. Skin immune sentinels in health and disease. Nature Rev Immunol. 2009;9:679–691. doi: 10.1038/nri2622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Littman DR, Rudensky AY. Th17 and regulatory T cells in mediating and restraining inflammation. Cell. 2010;140:845–858. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pabst O. New concepts in the generation and functions of IgA. Nature Rev Immunol. 2012;12:821–832. doi: 10.1038/nri3322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ashida H, Ogawa M, Kim M, Mimuro H, Sasakawa C. Bacteria and host interactions in the gut epithelial barrier. Nature Chem Biol. 2011;8:36–45. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.van Nood E, et al. Duodenal infusion of donor feces for recurrent Clostridium difficile. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:407–415. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1205037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kamada N, et al. Regulated virulence controls the ability of a pathogen to compete with the gut microbiota. Science. 2012;336:1325–1329. doi: 10.1126/science.1222195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Cornforth DM, Foster KR. Competition sensing: the social side of bacterial stress responses. Nature Rev Microbiol. 2013;11:285–293. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Arthur JC, et al. Intestinal inflammation targets cancer-inducing activity of the microbiota. Science. 2012;338:120–123. doi: 10.1126/science.1224820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Couturier-Maillard A, et al. NOD2-mediated dysbiosis predisposes mice to transmissible colitis and colorectal cancer. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:700–711. doi: 10.1172/JCI62236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hu B, et al. Microbiota-induced activation of epithelial IL-6 signaling links inflammasome-driven inflammation with transmissible cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:9862–9867. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1307575110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Khor B, Gardet A, Xavier RJ. Genetics and pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature. 2011;474:307–317. doi: 10.1038/nature10209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Houlston RS, et al. Meta-analysis of three genome-wide association studies identifies susceptibility loci for colorectal cancer at 1q41, 3q26.2, 12q13.13 and 20q13.33. Nature Genet. 2010;42:973–977. doi: 10.1038/ng.670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]