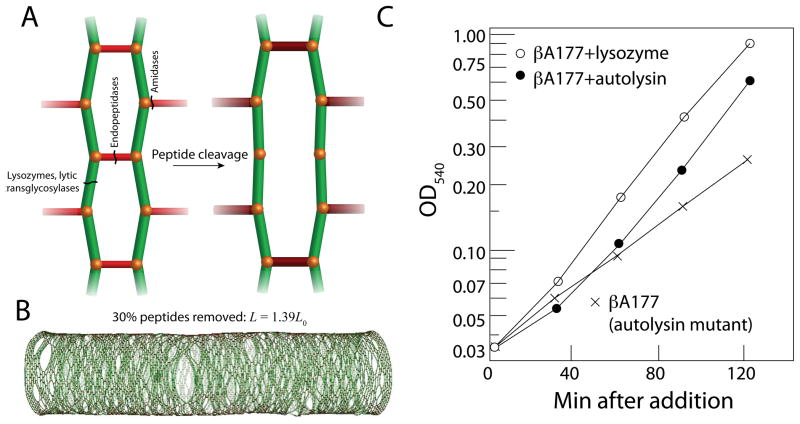

Figure 1. The role of hydrolases in cell-wall expansion.

(A) Specific hydrolases cleave crosslinks (red) between glycan strands (green), at the root of the peptide stem, or between glycan subunits. Cleavage of crosslinks transfers stress to the surrounding material (size and color of peptides indicate the amount of extension), leading to stretching of the PG network. (B) In silico, the removal of 30% of the crosslinks from a rod-shaped, Gram-negative PG network causes the cell to become longer, but does not affect the mechanical integrity of the cell wall or its shape, suggesting that organisms such as E. coli can tolerate large fluctuations in hydrolase activity. (C) A mutation in a B. subtilis gene encoding an autolysin results in lower levels of PG hydrolysis and a slower growth rate (crosses) relative to wild-type cells. The growth rate of the mutant can be increased by adding purified autolysin (filled circles) or lysozyme (open circles), indicating that hydrolysis is a major determinant of elongation and growth rate. (B) is modified from Ref. [11]; (C) is modified from Ref. [17].