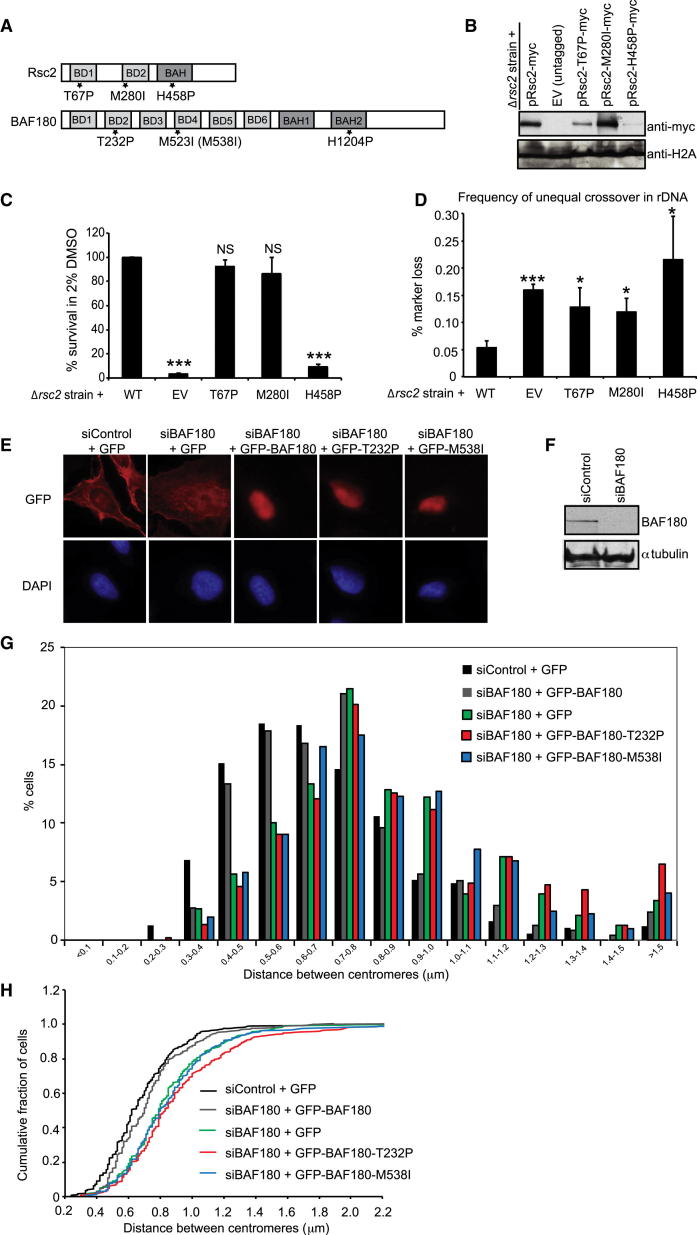

Figure 3.

Mutations Identified in BAF180 from Cancer Samples Result in Impaired Cohesin-Dependent Functions in Yeast and Mammals

(A) Illustration of domain organization and relative position of cancer-associated mutations in Rsc2 and BAF180. BDs and BAH domains are numbered sequentially.

(B) Analysis of WT and mutant Rsc2 expression levels in total protein preparations by western blotting. Loading control: anti-H2A.

(C) Hypersensitivity to DMSO as a readout of Rsc2-dependent transcriptional activity was analyzed by plating serial dilutions of the indicated mid-log cultures onto media with or without 2% DMSO.

(D) Frequency of unequal rDNA crossover events in yeast strains containing the indicated Rsc2 expression construct.

(E) Expression of GFP-tagged BAF180 constructs in siBAF180 U20S. Cells were treated as in (G) and Figure S4, for IF-FISH. IF using anti-GFP shows GFP or GFP-BAF180 expression in the red channel.

(F) Analysis of BAF180 depletion efficiency in U2OS cells by western blotting. Anti-tubulin was used as a loading control.

(G) FISH analysis of G2 phase U2OS cells transfected with the indicated BAF180 expression construct using a probe against centromere 10. The distances between signals were measured and the distribution was plotted as a histogram.

(H) The data in (G) are presented as a cumulative plot to further illustrate the defect in cohesion in cells transfected with cancer-associated mutants. Statistical analysis of the data presented in (G) and (H) showed that rescue of the cohesion defect by reintroduction of WT BAF180 (siBAF180 + GFP-BAF180) was significant (p < 0.001). In contrast, centromeric cohesion in cells expressing the cancer mutants was not significantly different from that in BAF180-depleted cells containing empty vector (siBAF180 + GFP; p = 0.06 for T232P and p = 0.37 for M538I), but was significantly different from that in cells with WT BAF180 reintroduced (p < 0.001 for both mutants compared with WT).

See also Figures S3 and S4.